Unhealthy Neighbourhood “Syndrome”: A Useful Label for Analysing and Providing Advice on Urban Design Decision-Making?

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Is “the neighbourhood” a useful (spatial) category for analysing, organising and offering advice to urban designers?

- (2)

- If so, is it reasonable to describe a neighbourhood as “healthy” or “unhealthy”?

- (3)

- What is the advantage of labelling the phenomenon of unhealthy neighbourhoods as a “syndrome”?

- (4)

- Additionally, if UNS is a useful diagnostic label for providing advice, what strategies can be adopted to mitigate the symptoms it is used to diagnose?

2. Research Design

Scope and Focus of Attention

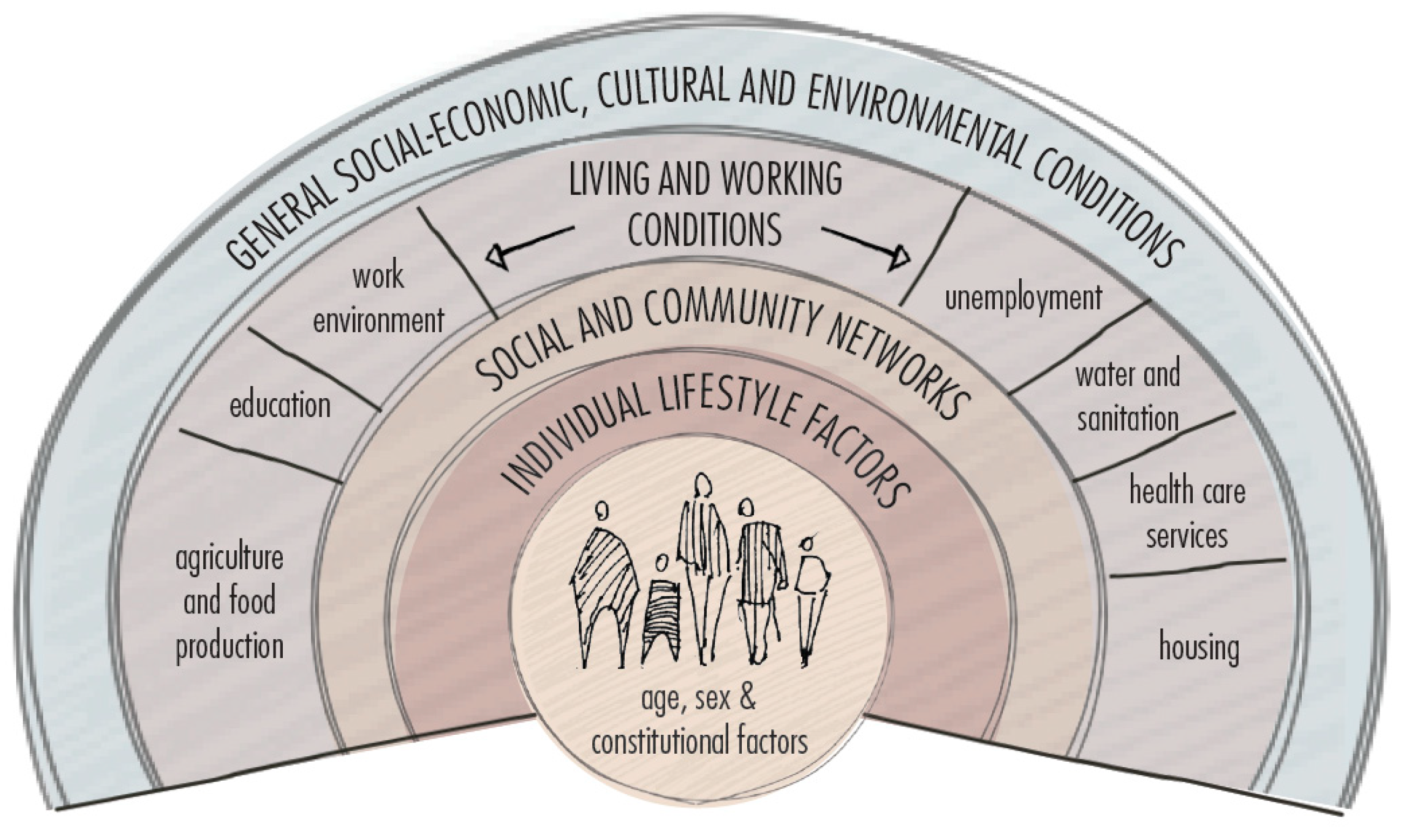

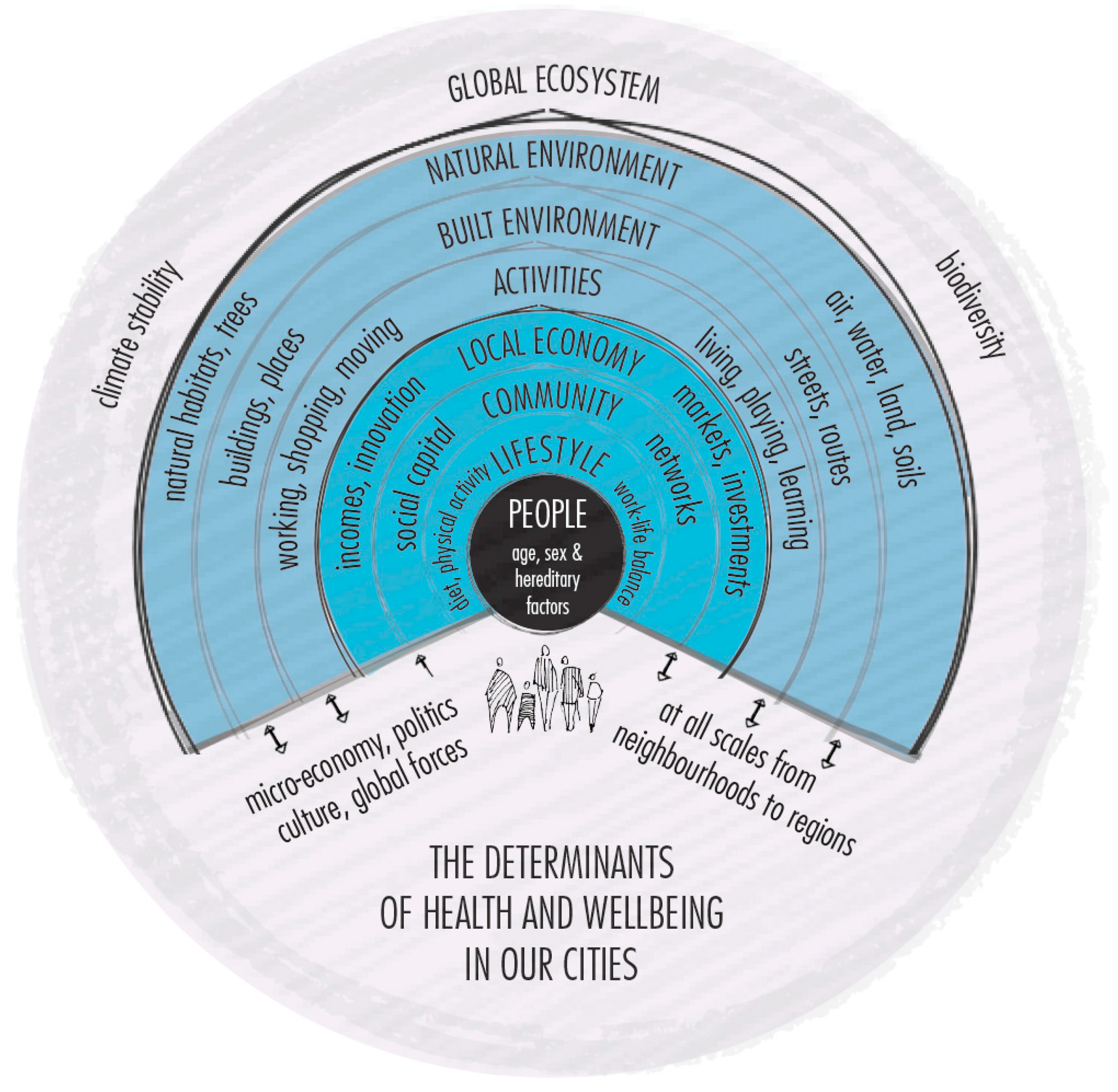

3. Part One: How the Built Environment Is Held to Affect Physical Health and Wellbeing at the Neighbourhood Scale

3.1. What Is Meant by “Neighbourhood” and by “Health and Wellbeing”?

3.2. “Problem” Neighbourhoods

3.3. The Depiction of the Health Effects of the Built and Natural Environments

3.4. Why “Unhealthy Neighbourhood Syndrome”?

3.5. Contributors to and Effects of UNS

4. Part Two: Manipulating Urban Design to Affect Physical Health and Mental Wellbeing at the Neighbourhood Scale

- better physical health: lower obesity, less type 2 diabetes, lower blood pressure, reduced heart disease, lower rates of asthma and respiratory disease, faster recovery from illness, and from fatigue;

- better general fitness: increased walking (for both travel and recreation), increased exercise, sport and recreation, and more cycling;

- greater daily comfort: reduced air pollution, heat stress, traffic noise and poor sanitation, and reduced exposure of lower socio-economic groups to the effects of debilitating neighbourhoods;

- enhanced quality of life in terms of increased sense of emotional wellbeing and satisfaction, greater happiness, reduced fear and higher energy levels;

- better mental health: less stress and more psychological restfulness, reduced depression, anxiety and anger, reduced psychosis).

4.1. Decisions about Urban Density

4.2. Decisions about Greenspace

4.3. Decisions about Movement

4.4. Decisions about the Location and Spatial Configuration of Housing

5. Synthesizing Advice on Mental Wellbeing

- limiting emissions and sufficient distance of receptors of pollutants through increased gross density encouraging active transportation and public transit

- locating a network of greenspace relative to homes and workplaces

- designing an attractive and walkable public realm, with active facades and a gradual transition between public and private spaces

- providing safe, well-lit, sociable spaces which are child-friendly with low traffic speeds

- enabling active travel and walkable access to daily needs, including healthy food and schools

- offering access to peaceful places and distancing from sources of pollution

- enhancing the quality of public spaces, through safe walking routes and connected green spaces

- employing features that help to express neighbourhood identity, and

- including flexible urban space that can accommodate neighbourhood modifications.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Is “the neighbourhood” a useful (spatial) category for analysing, organising, and offering advice to urban designers?

“One of the most fundamental steps in geographical research is the creation of meaningful and appropriate spatial units of analysis. In some cases, such units are predefined and logical, but in most instances, geographers (and others) are forced either to use whatever spatial units are available or to construct [those] that make as much sense as possible.”

- (2)

- If so, is it useful to describe a neighbourhood as “healthy” (or indeed “unhealthy”)?

- (3)

- What is the advantage of labelling the phenomenon of unhealthy neighbourhoods as a “syndrome”?

- (4)

- Additionally, if UNS is a useful diagnostic label for providing advice, what strategies can be adopted to mitigate the symptoms it is used to diagnose?

- recognising that such neighbourhoods display an array of symptoms affecting both physical health and mental wellbeing

- assembling broadly based multi-disciplinary teams with the wide-ranging skills and expertise necessary to address this broad array of symptoms, and

- deploying these skills through longitudinal programmes of parallel workstreams capable of tackling the particular symptoms presented.

- present a more holistic and inclusive definition of what constitutes unhealthy neighbourhoods, whilst acknowledging the direct and indirect effects of broader economic, environmental forces on desired outcomes in terms of physical health and mental wellbeing;

- expand the evidence bases called upon by urban designers and associated professionals when deciding what contributes to poor physical and mental health, thereby demonstrating critical obstacles as well as signposting future directions;

- help to further demonstrate the economic, social and environmental costs of inadequate neighbourhood urban design and their contribution to poor physical health and mental wellbeing;

- increase both professional and public awareness of the effects of neighbourhood urban design on health and wellbeing;

- lead to developments of incentivized programmes and policies for encouraging politicians, professionals, as well as building owners, to adopt the actions required to move towards healthier neighbourhoods; and

- aid the identification of who are the principal actors, the prime movers, for putting this agenda into practice.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parker, G.; Salter, K.; Wargent, M. Neighbourhood Planning in Practice; Lund Humphries: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AlWaer, H.; Illsley, B. (Eds.) Rethinking Masterplanning: Creating Quality Places; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- AlWaer, H.; Cooper, I. A Review of the Role of Facilitators in Community-Based, Design-Led Planning and Placemaking Events. Built Environ. 2019, 45, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlWaer, H.; Cooper, I. Changing the Focus: Viewing Design-Led Events within Collaborative Planning. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husam, A.; Rintoul, S.; Cooper, I. An investigation into decision-making and delivery activities following design-led events in collaborative planning. Archnet-IJAR 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fred, L. Healthy Placemaking: Wellbeing through Urban Design; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Croome, D. Designing Buildings for People: Sustainable Liveable Architecture; The Crowood Press Ltd.: Wiltshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S.S. The just city. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2014, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudlin, D.; Falk, N. Sustainable Urban Neighbourhood: Building the 21st Century Home; Routledge: Thames, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H. City of Well-Being: A Radical Guide to Planning; Taylor & Francis: Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.; Hincks, S.; Sherriff, G. Getting involved in plan making: Participation and stakeholder involvement in local and regional spatial strategies in England. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2010, 28, 574–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineo, H.; Rydin, Y. Cities, Health and Well-Being; RICS, Parliament Square: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M.; Guise, R. Shaping Neighbourhoods: For Local Health and Global Sustainability; Routledge: Thames, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M. A health map for the local human habitat. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2006, 126, 252–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; AlWaer, H.; Omrany, H.; Alalouch, C.; Clements-Croome, D.; Tookey, J. Sick building syndrome: Are we doing enough? Archit. Sci. Rev. 2018, 61, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineo, H.; Glonti, K.; Rutter, H.; Zimmermann, N.; Wilkinson, P.; Davies, M. Urban health indicator tools of the physical environment: A systematic review. J. Urban Health 2018, 95, 613–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Bird, E.; Ige, J.; Burgess-Allen, J.; Pilkington, P. Spatial Planning for Health: An Evidence Resource for Planning and Designing Healthy Places. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/spatial-planning-for-health-evidence-review (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Wheaton, B.; Nisenbaum, R.; Glazier, R.H.; Dunn, J.R.; Chambers, C. The neighbourhood effects on health and well-being (NEHW) study. Health Place 2015, 31, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M.; Beautyman, I. Scottish Health and Inequalities Effect Assessment Network. Available online: https://www.improvementservice.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/19740/20-minute-neighbourhood-rapid-scoping-assessment.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Carmona, M. Place value: Place quality and its effect on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, B.; Salama, A.M.; McInneny, A. Architecture, urbanism and health in a post-pandemic virtual world. Archnet-IJAR 2021, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.M. Coronavirus questions that will not go away: Interrogating urban and socio-spatial implications of COVID-19 measures. Emerald Open Res. 2020, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Town Planning Institute. Enable Healthy Placemaking. 2020. Available online: https://www.rtpi.org.uk/media/5777/enabling-healthy-placemaking.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Public Health England. Beyond the Data: Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 on BAME Groups. 2020. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/892376/COVID_stakeholder_engagement_synthesis_beyond_the_data.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.M.; Hodge, C. Beyond Storms & Droughts: The Psychological Effects of Climate Change; American Psychological Association and Eco America: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupton, R.; Power, A. What We Know about Neighbourhood Change: A Literature Review; CASE Report, (27); Centre for the Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The Young Foundation. How Can Neighbourhoods Be Understood and Defined? The Young Foundation: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Talen, E. Neighborhood; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guise, R.; Webb, J. Characterising Neighbourhoods: Exploring Local Assets of Community Significance; Routledge: Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, L. The Neighborhood and the Neighborhood Unit. Town Plan. Rev. 1954, 24, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. Good City Form; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- The Urban Task Force. Towards an Urban Renaissance; Routledge: Thames, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Galster, G. On the nature of neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2111–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H.; Horswell, M.; Millar, P. Neighbourhood accessibility and active travel. In Routledge Handbook of Physical Activity Policy and Practice; Routledge: Thames, UK, 2017; pp. 186–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kropf, K. The Handbook of Urban Morphology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, D. Soft City: Building Density for Everyday Life; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinert, S.; Horton, R. Urban design: An important future force for health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 388, 2848–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M. Covid-19, Place-making and Health. Planning. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Phillips, D. Catching Up or Falling Behind? Geographical Inequalities in the UK and How They Have Changed in Recent Years; The Institute for Fiscal Studies: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Future Place Leadership. Placemaking in the Nordics. Available online: https://mb.cision.com/Public/19081/3120813/972a556ba01f0b3f.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2001, 42, 258–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakerson, R.J.; Clifton, J.D. The Neighborhood as Commons: Reframing Neighborhood Decline. Fordham URB LJ 2017, 44, 411. [Google Scholar]

- Kind, A.J.; Buckingham, W.R. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible—The neighborhood atlas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durfey, S.N.; Kind, A.J.; Buckingham, W.R.; DuGoff, E.H.; Trivedi, A.N. Neighborhood disadvantage and chronic disease management. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 54, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, D.S. The age of extremes: Concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography 1996, 33, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.; Duncan, C. Individuals and their ecologies: Analysing the geography of chronic illness within a multilevel modelling framework. Health Place 1995, 1, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeClere, F.B.; Rogers, R.G.; Peters, K.D. Ethnicity and mortality in the United States: Individual and community correlates. Soc. Forces 1997, 76, 169–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtice, J.; Ellaway, A.; Robertson, C.; Morris, G.; Allardice, G.; Robertson, R. Public Attitudes and Environmental Justice in Scotland; Scottish Executive Social Research: Edinburgh, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.B.; Covington, J. Community structural change and fear of crime. Soc. Probl. 1993, 40, 374–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaroop, S.; Krysan, M. The determinants of neighborhood satisfaction: Racial proxy revisited. Demography 2011, 48, 1203–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwiers, M.; Bolt, G.; Van Ham, M.; Van Kempen, R. The global financial crisis and neighbourhood decline. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 664–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchman, C.W. Guest Editorial: Wicked Problems. Manag. Sci. 1967, 14, B141–B142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, R.; Musterd, S. Area-based policies: A critical appraisal. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gent, W.P.; Mustard, S.; Ostendorf, W. Disentangling neighbourhood problems: Area-based interventions in Western European cities. Urban Res. Pract. 2009, 2, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineo, H.; Zimmermann, N.; Cosgrave, E.; Aldridge, R.W.; Acuto, M.; Rutter, H. Promoting a healthy cities agenda through indicators: Development of a global urban environment and health index. Cities Health 2018, 2, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, M.; Dahlgren, G. What can be done about inequalities in health? Lancet 1991, 338, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. In Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/key_concepts_en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Brundtland, G.H. What is sustainable development. In Our Common Future; The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED): New York, NY, USA, 1985; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service. Sick Building Syndrome. 2020. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/sick-building-syndrome/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- WHO. World Health Organization. Indoor Air Pollutants: Exposure and Health Effects. Euro Rep. Stud. 1983, 78, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia. Syndrome. 2021. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syndrome (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- The British Medical Association. The British Medical Association Illustrated Medical Dictionary; Dorling Kindersley: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pascale, C.-M. (Ed.) Social Inequality and the Politics of Representation; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, C. Happy City: Transforming Our Lives through Urban Design; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beenackers, M.A.; Groeniger, J.O.; Kamphuis, C.B.; Van Lenthe, F.J. Urban population density and mortality in a compact Dutch city: 23-year follow-up of the Dutch GLOBE study. Health Place 2018, 53, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.; Boyko, C. The Little Book of Density; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H. Land use planning and health and well-being. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, S115–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D.; Andresen, M.A.; Schmid, T.L. Obesity relationships with community design, physical activity, and time spent in cars. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Land Commission. Vacant and Derelict Land in Scotland Assessing the Effect of Vacant and Derelict Land on Communities. 2019. Available online: https://www.landcommission.gov.scot/downloads/5dd7d4dfa39b6_VDL%20in%20Scotland%20Final%20Report%2020191008.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Lõhmus, M.; Balbus, J. Making green infrastructure healthier infrastructure. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2015, 5, 30082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Yates, G. The built environment and health: An evidence review. In Brief Paper of Glasgow Centre for Population Health; Glasgow Centre for Population Health Publications: Glasgow UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin, H. Urban sprawl and public health. Public Health Rep. 2002, 117, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Schmid, T.; Killingsworth, R.; Zlot, A.; Raudenbush, S. Relationship between Urban Sprawl and Physical Activity, Obesity, and Morbidity—Update and Refinement. Health Place 2014, 26, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. The Effects of Sprawl on Neighborhood Social Ties. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2001, 67, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.; Zegeer, C.; Huang, H.; Cynecki, M. A Review of Pedestrian Safety Research in the United States and Abroad; Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, M.; Thompson, J.; de Sá, T.H.; Ewing, R.; Mohan, D.; McClure, R.; Roberts, I.; Tiwari, G.; Giles-Corti, B.; Sun, X.; et al. Land use, transport, and population health: Estimating the health benefits of compact cities. Lancet 2016, 388, 2925–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Uzzell, D. Affective appraisals of the daily commute: Comparing perceptions of drivers, cyclists, walkers, and users of public transport. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, G.; Chatterjee, K. A human perspective on the daily commute: Costs, benefits and trade-offs. Transp. Rev. 2008, 28, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, T.; Nishikido, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Kaneko, T.; Kabuto, M. Long commuting time, extensive overtime, and sympathodominant state assessed in terms of short-term heart rate variability among male white-collar workers in the Tokyo megalopolis. Ind. Health 1998, 36, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costal, G.; Pickup, L.; Di Martino, V. Commuting—A further stress factor for working people: Evidence from the European Community. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 1988, 60, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, S.M.; Rotton, J. Type of commute, behavioral aftereffects, and cardiovascular activity: A field experiment. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koslowsky, M.; Kluger, A.N.; Reich, M. Commuting Stress: Causes, Effects, and Methods of Coping; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B.; Stutzer, A. The Economics of Happiness. World Econ. 2002, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (RCEP). The Urban Environment; RCEP: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government. Scotland’s People. In Annual Report: Results from 2012 Scottish Household Survey; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, H.A.; Rasmussen, B.; Ekholm, O. Neighbour noise annoyance is associated with various mental and physical health symptoms: Results from a nationwide study among individuals living in multi-storey housing. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Kingdom Green Building Council. Health and Wellbeing in Homes. 2016. Available online: https://www.ukgbc.org/sites/default/files/08453%20UKGBC%20Healthy%20Homes%20Updated%2015%20Aug%20(spreads).pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Improving Air Quality in the UK, Tackling Nitrogen Dioxide in Our Towns and Cities, UK Overview Document, December 2015. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/486636/aq-plan-2015-overview-document.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Yuchi, W.; Sbihi, H.; Davies, H.; Tamburic, L.; Brauer, M. Road proximity, air pollution, noise, green space and neurologic disease incidence: A population-based cohort study. Environ. Health 2020, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustrans. The Role of Active Travel in Improving Health. Toolkit Part 2: Improving Air Quality by Walking and Cycling. 2017. Available online: https://www.sustrans.org.uk/media/4467/improving_air_quality_walking_cyling.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Levinson, A. Valuing public goods using happiness data: The case of air quality. J. Public Econ. 2012, 96, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Folmer, H.; Xue, J. To what extent does air pollution affect happiness? The case of the Jinchuan mining area, China. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 99, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, C.; Thompson, H. Housing improvement and health: Research findings. In Health Effect Assessment of Housing Improvements: A Guide; Scottish Health and Inequalities Effect Assessment Network: Glasgow, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- King, K. Jane Jacobs and ‘The Need for Aged Buildings’: Neighbourhood Historical Development Pace and Community Social Relations. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 2407–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kluizenaar, Y.; Roda, C.; Dijkstra, N.E.; Fossati, S.; Mandin, C.; Mihucz, V.G.; Hänninen, O.; Fernandes, E.D.O.; Silva, G.V.; Carrer, P.; et al. Office Characteristics and Dry Eye Complaints in European Workers—The OFFICAIR Study. Build. Environ. 2016, 102, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, F.-L.; Hashim, Z.; Said, S.M.; Than, L.T.-L.; Hashim, J.H.; Norbäck, D. Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) among Office Workers in a Malaysian University—Associations with Atopy, Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FeNO) and the Office Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 536, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Deng, Q.; Li, Y.; Sundell, J.; Norbäck, D. Outdoor Air Pollution, Meteorological Conditions and Indoor Factors in Dwellings in Relation to Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) Among Adults in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 560–561, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, K.; Turner, L.R.; Tong, S. Floods and human health: A systematic review. Environ. Int. 2012, 47, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foudi, S.; Osés-Eraso, N.; Galarraga, I. The effect of flooding on mental health: Lessons learned for building resilience. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 5831–5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A. Definitions of Crowding and the Effects of Crowding on Health. A Literature Review Prepared for the Ministry of Social Policy; The Ministry of Social Policy: Wellington, New Zealand, 2001.

- McCrea, R.; Shyy, T.K.; Stimson, R. What is the Strength of the Link Between Objective and Subjective Indicators of Urban Quality of Life? Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2006, 1, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lättman, K.; Olsson, L.E.; Friman, M.; Fujii, S. Perceived Accessibility, Satisfaction with Daily Travel, and Life Satisfaction among the Elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjornstrom, E.E.S.; Ralston, M.L. Neighborhood Built Environment, Perceived Danger, and Perceived Social Cohesion. Environ. Behav. 2016, 46, 718–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindal, P.J.; Hartig, T. Architectural variation, building height, and the restorative quality of urban residential streetscapes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Carrus, G.; Bonaiuto, M. Is it really nature that restores people? A comparison with historical sites with high restorative potential. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, E.; Branas, C.; Keddem, S.; Sellmen, J.; Cannuscio, C. More than just an eyesore: Local insights and solutions on vacant land and urban health. J. Urban Health 2013, 90, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, P.; Hamstead, Z.A.; McPhearson, T. A social-ecological assessment of vacant lots in New York City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 120, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, L.; Kearns, A.; Mason, P.; Tannahill, C.; Egan, M.; Whitely, E. Exploring the relationships between housing, neighbourhoods and mental wellbeing for residents of deprived areas. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, H.J.; Hur, M. The relationship between walkability and neighbourhood social environment: The importance of physical and perceived walkability. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 62, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karssenberg, H.; Laven, J.; Glaser, M.; Van’t Hoff, M. The city at eye level. In The City at Eye Level: Lessons for Street Plinths; Eburon Academic Publishers: Delft, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings; Using Public Space: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, R.; Marshall, G. From lonely cities to prosocial places: How evidence-informed urban design can reduce the experience of loneliness. In Narratives of Loneliness; Routledge: Thames, UK, 2017; pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.J. Bus Stop Urban Design. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria, S.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Shea, S.; Borrell, L.N.; Jackson, S. Associations of neighborhood problems and neighborhood social cohesion with mental health and health behaviors: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Health Place 2008, 14, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D. Blues from the neighborhood? Neighborhood characteristics and depression. Epidemiol. Rev. 2008, 30, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zammit, S.; Lewis, G.; Rasbash, J.; Dalman, C.; Gustafsson, E.; Allebeck, P. Individuals, schools and neighbourhood: A multi-level longitudinal study of variation in incidence of psychotic disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerswald, C.L.; Lin, J.S.; Parriott, A. Six-year mortality in a street-recruited cohort of homeless youth in San Francisco, California. PeerJ 2016, 4, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maness, D.L.; Khan, M. Care of the homeless: An overview. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 89, 634–640. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel, M.; Sheward, R.; de Cuba, S.E.; Coleman, S.M.; Frank, D.A.; Chilton, M.; Black, M.; Heeren, T.; Pasquariello, J.; Casey, P.; et al. Unstable housing and caregiver and child health in renter families. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20172199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, C. The child in the city. Society 1978, 15, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiher, H. Shaping Daily Life in Urban Environments. In Children in the City: Home, Neighbourhood and Community; Christensen, P., O’Brien, M., Eds.; Routledge Falmer: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 66–81. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, P.; O’Brien, M. Children in the City: Home Neighbourhood and Community; Routledge: Thames, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Manchester, H.; Facer, K. (Re)-Learning the City for Intergenerational Exchange. In Learning the City; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderbeck, R.; Worth, N. Intergenerational Space; Routledge: Thames, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, W. Intergenerational cities: A framework for policies and programs. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2011, 9, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Chan, A. Families, friends, and the neighborhood of older adults: Evidence from public housing in Singapore. J. Aging Res. 2011, 2012, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, A.E.; Molnar, L.J.; Eby, D.W.; Adler, G.; Bedard, M.; Berg-Weger, M.; Classen, S.; Foley, D.; Horowitz, A.; Kerschner, H.; et al. Transportation and aging: A research agenda for advancing safe mobility. Gerontologist 2007, 47, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, R.C.; Richards, M.H. The after-school needs and resources of a low-income urban community: Surveying youth and parents for community change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 45, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.E.; Ziersch, A.M.; Zhang, G.; Osborne, K. Do perceived neighbourhood cohesion and safety contribute to neighbourhood differences in health? Health Place 2009, 15, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, T. The fear of crime and area differences in health. Health Place 2001, 7, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziersch, A.M.; Baum, F.E.; Macdougall, C.; Putland, C. Neighbourhood life and social capital: The implications for health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, C. Fear of crime: A review of the literature. Int. Rev. Vict. 1996, 4, 79–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, S.; Ellaway, A. Ecological approaches: Rediscovering the role of the physical and social environment. In Social Epidemiology; Berkman, L.F., Kawachi, I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 332–348. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, G.; McNeill, L.; Wolin, K.; Duncan, D.; Puleo, E.; Emmons, K. Safe to walk? Neighborhood safety and physical activity among public housing residents. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, R.; Gemmell, I.; Heller, R. The population effect of crime and neighbourhood on physical activity: An analysis of 15,461 adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stronegger, W.J.; Titze, S.; Oja, P. Perceived characteristics of the neighborhood and its association with physical activity behavior and self-rated health. Health Place 2010, 16, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokols, D.; Shumaker, S.A. The Psychological Context of Residential Mobility and Weil-Being. J. Soc. Issues 1982, 38, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, R.M.; Strazdins, L.; Clements, M.S.; Broom, D.H.; Parslow, R.; Rodgers, B. The health effects of jobs: Status, working conditions, or both? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2005, 29, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kershaw, K.N.; Mezuk, B.; Abdou, C.M.; Rafferty, J.A.; Jackson, J.S. Socioeconomic position, health behaviors, and C-reactive protein: A moderated-mediation analysis. Health Psychol. 2010, 29, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowe, R.P.; Peek, M.K.; Perez, N.A.; Yetman, D.L.; Cutchin, M.P.; Goodwin, J.S. Herpesvirus reactivation and socioeconomic position: A community-based study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2010, 64, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajrasouliha, A.; Del Rio, V.; Francis, J.; Edmondson, J. Urban form and mental wellbeing: Scoping a theoretical framework for action. J. Urban Spaces Ment. Health 2018, 5. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Urban-form-and-mental-wellbeing%3A-scoping-a-for-Hajrasouliha-Rio/85b21cdf4fa0a04a43c2db78ba6bdc3ccdce4177#paper-header (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Talen, E.; Koschinsky, J. Compact, walkable, diverse neighborhoods: Assessing effects on residents. Hous. Policy Debate 2014, 24, 717–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Holt, J.B.; Lu, H.; Onufrak, S.; Yang, J.; French, S.P.; Sui, D.Z. Neighborhood commuting environment and obesity in the United States: An urban-rural stratified multilevel analysis. Prev. Med. 2014, 59, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Taylor, T.; Wheeler, B.W.; Spencer, A.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Recreational physical activity in natural environments and implications for health: A population based cross-sectional study in England. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Lawson, K.D.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Finkelstein, E.A.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Van Mechelen, W.; Pratt, M. Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. The economic burden of physical inactivity: A global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2013, 388, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogen, Y. Assessing nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels as a contributing factor to the coronavirus (COVID-19) fatality rate. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 138605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, J.M.; Wolf, K.L.; Backman, D.R.; Tretheway, R.L.; Blain, C.J.; O’Neil-Dunne, J.P.; Frank, L.D. Multiple Health Benefits of Urban Tree Canopy: The Mounting Evidence for a Green Prescription. Health Place 2016, 42, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. The relationships between urban parks, residents’ physical activity, and mental health benefits: A case study from Beijing, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 190, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; CUP Archive: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Natural versus urban scenes: Some psychophysiological effects. Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 523–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Aspinall, P. The restorative outcomes of forest school and conventional school in young people with good and poor behaviour. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Mitchell, L.; Stride, C. Bed of roses? The role of garden space in older people’s well-being. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Urban Des. Plan. 2015, 168, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, M.D.; Fry, G.; Tveit, M. Health effects of viewing landscapes–Landscape types in environmental psychology. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The nature of the view from home: Psychological benefits. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, V.I.; Pearson-Mims, C.H. Responses to scenes with spreading, rounded, and conical tree forms. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 667–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzeval, M.; Bond, L.; Campbell, M.; Egan, M.; Lorenc, T.; Petticrew, M.; Popham, F. How does Money Influence Health? In Improving Access to Greenspace: A New Review for 2020; PHE Publications; Public Health England: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service. Exercise Health Benefits. 2020. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/exercise-health-benefits/ (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Sinnett, D.; Chatterjee, K.; Williams, K.; Cavill, N. Creating built environments that promote walking and health: A review of international evidence. J. Dep. Plan. Archit. 2012, 4, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Luckenbill, J.; Subramaniam, A.; Thompson, J. This Is Play: Environments and Interactions that Engage Infants and Toddlers; National Association for the Education of Young Children: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=5968834 (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Boyko, C.T.; Cooper, R.; Cooper, C. Measures to assess well-being in low-carbon-dioxide cities. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Urban Des. Plan. 2015, 168, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Helfand, S.; Woolf, K.; Lohr, C.; Mulrow, S.; Teutsch, S.; Atkins, D. Current methods of the US Preventative Services Task Force: A review of the process. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.; Lorch, R. (Eds.) Buildings, Culture and Environment: Informing Local and Global Practices; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gatzweiler, F.; Corburn, J.; Moran Flores, E.; Fuders, F.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Ke, X.; Rozenblat, C.; Wang, L.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Y. The Little Book of the Health of Cities; Cooper, R., Coulton, C., Eds.; Imagination Lancaster: Lancaster, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-86220-368-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ravetz, J. Master planning by and for the urban shared mind: Towards a ‘neighbourhood 3.0’. In Placemaking: Rethinking the Master Planning Process; Al Waer, H., Illsley, B., Eds.; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2017; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- United Kingdom Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence. 2020. Available online: https://housingevidence.ac.uk/publications/effect-of-housing-design-and-placemaking-on-social-value-and-wellbeing-in-the-pandemic-interim-report/ (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- AlWaer, H.; Cooper, I. Built environment professionals and the call for a ‘new’ professionalism. In Rethinking Masterplanning: Creating Quality Places; AlWaer, H., Illsley, B., Eds.; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2017; pp. 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, I. Inadequate grounds for a ‘design-led’ approach to urban renaissance? Build. Res. Inf. 2000, 28, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.J. Navigating Climate Change: Rethinking the Role of Buildings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.; Lorenz, D. Rethinking professionalism: Guardianship of land and resources. Build. Res. Inf. 2011, 39, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E. Plan vs. Process: The Case of Neighbourhood Planning. Built Environ. 2019, 45, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, D.C. Defining Spatial Units in Geographic Research. Prof. Geogr. 1996, 48, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Chan, J. Analogical arguments, Critical Thinking Web, Hong Kong University. 2021. Available online: https://philosophy.hku.hk/think/arg/analogy.php (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Janda, K.; Parag, Y. A middle-out approach for improving energy performance in buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 41, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K.; Janda, K.B.; Owen, A. Preparing ‘middle actors’ to deliver zero-carbon building transitions. Build. Cities 2020, 1, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaatouq, A.; Noriega-Campero, A.; Alotaibi, A.; Krafft, P.; Moussaid, M.; Pentland, A. Adaptive social networks promote the wisdom of crowds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11379–11386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mumford [31] | “neighbourhoods, in some annoying, inchoate fashion exist wherever human beings congregate, in permanent family dwellings; and many of the functions of the city tend to be distributed naturally—that is, without any theoretical preoccupation or political direction—into neighbourhoods” (p. 258). |

| Jacobs [32] | Neighbourhoods can be defined at three levels of geographic and political organization: the street level, district level, and city-level. |

| Lynch [33] | Unit of social analysis Territorial base of socially supportive group Defined spatial unit Catchment of services, elementary school |

| The Urban Task Force [34] | By itself, housing does not make a neighbourhood. Neighbourhoods need to comprise a mix of uses which work together to encourage formal and informal transactions, sustaining activity throughout the day. The mixing of different activities within an area should serve to strengthen social integration and civic life. |

| Galster [35] Lupton and Power [27] | Attributes of neighbourhoods—from geographic to social Environmental—topography, pollution Proximity—location, transport infrastructure Buildings—type, design, material, density, repair Infrastructure—roads, streetscape Demography—age profile, class status, ethnic diversity, mobility of population Existence and quality of local services Social-interactive—friend and family networks, local associations, informal interactions, social control mechanisms Sentiment—identification with place, historical significance, local stories Political—local parties, political networks, resident involvement |

| The Young Foundation [28] Barton and Hills [36] | Neighbourhoods are ultra-local communities of place. Most people feel that they intuitively understand what they mean, in the shape of neighbourly interactions, mutual support, gathering places and a friendly, attractive environment–or in a “bad neighbourhood”, danger, anti-social interaction, exclusiveness, isolation and dereliction. Local service catchments areas, based on walking distance. |

| Talen [29] | A spatial unit that people relate to. A neighbourhood is often conceptualized around three dimensions: size/shape: defined through the types of edges that provide boundaries. The edges can be human-made or natural and be different in character or type. Function: characterized by the location of functions, such as civic buildings, public space, or commercial uses. Morphology: The pattern of streets, blocks, lots, and buildings. Such patterns can have a significant effect on neighbourhood quality, character, and functionality. |

| Kropf [37] | A starting point for identifying the neighbourhood structure of a settlement is to locate the sub-centres and repeating pattens of associated uses. For example, retail, education, worship, community and recreational facilities can constitute sub-centres and may correlate with the more loosely defined and socially based unit of the neighbourhood. |

| Sim [38] | “neighbourhood is a state of being in a relationship. More than anything, the human environment is about relationships: relationships between people and planet, relationships between people and place, and relationships between people and people” (p. 37). |

| UNS: Physical Environment Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Environment Factors | Effects | Outcomes | Identified Symptoms Associated with UNS |

| Low density | Low density can encourage less physical activity and walking. | Obesity, prevalence of hypertension, and mortality | Beenackers et al. [67] found that higher population density was modestly related to higher mortality. Cooper and Boyko [68] also suggested that high density can result in depression, strain, withdrawal, cognitive development, and reduced friendliness. |

| Land use patterns | Decisions about land use decisions can result in an increase in car use and a decrease in active transportation. | Cardiovascular disease, stroke and all-cause mortality | The management of land is also held to contribute to poor mental and physical health by affecting the location of goods and services. For example, Barton [69] reported that supermarket proximity can influence the availability of healthy food options, the absence of which can lead to poor diet and obesity. Land use patterns can also encourage car use if, for example, employment locations are isolated without sufficient public transportation options. Frank et al. [70] (p. 1) identified “land-use mix” as having “a strong association with obesity (BMI30 kg/m2), with each quartile increase being associated with a 12.2% reduction in the likelihood of obesity across gender and ethnicity”. |

| They can also aggravate access to healthy food options. | Poor diet and obesity | ||

| Vacant and Derelict Land (VDL) | VDL can negatively affect community wellbeing, and community perceptions of the local area. VDL may inhibit or prohibit movement through an area restricting social interaction influencing feelings of personal safety. | Increased anxiety levels, agitation and anger Increased incidence of crime and antisocial behaviours | The Scottish Land Commission [71] reported a spatial association between interaction with VDL and physical health, recording poorer health outcomes, population health and life expectancy. VDL may also inhibit or prohibit movement through an area by influencing feelings of personal safety and by restricting interaction/use due to fencing and hoardings. As well as these direct affects, VDL was reported to have significant effects on a community’s perceptions of its local area. |

| Greenness and connect with nature | A lack of accessible greenspace can lead to less social interaction and physical activity. | Lower mental wellbeing, increased stress, inactivity and less social activity | Urban greenspace [72] is also reported to have a negative effect on health by exposing people to “allergenic pollen, infections transmitted by arthropod vectors such as ticks or mosquitoes, and risk of injuries”. Additionally, a systematic review by Jones and Yates for the Glasgow Centre for Population Health [73] (p. 15) found decreased access to greenspace is associated with “lower mental wellbeing, increased stress, inactivity and less social activity”. |

| Spatial Configuration | Urban sprawl can lead to greater car use and less use of active transportation options. | Undermined social ties leading to lower mental health Obesity and prevalence of hypertension | The spatial configuration of a neighbourhood is also reported to contribute to poor physical health and mental wellbeing. As neighbourhood is a physical and social construction, according to Barton [10] (p. 101) “each person conceives their own neighbourhood, depending on where they live, what connections they have locally” and that “it is vital that spatial patterns do not frustrate these very varied individual connections, but facilitate them”. Sim [38] (p. 359) described space with no or little spatial clarity or sense of containment as lacking a sense of identity and shared ownership; wide open spaces that do not encourage social interaction and repel human activity prevent a sense of ownership from emerging (ibid.). Frumkin [74] presented sprawl (i.e., unrestricted urban development over a wide area of land) as contributing to negative health consequences through loss of social capital, social stratification, higher air pollution and health stress, physical inactivity and obesity. Ewing et al. [75] portrayed sprawl as reducing minutes walked so leading to higher obesity and prevalence of hypertension. Freeman [76] depicted sprawl and vehicle-based urbanism as undermining social ties among neighbourhoods, as discouraging residents from interacting with their neighbours. |

| Transportation | Prioritizing private car travel can contribute to longer commuting times, fatigue and chronic stress. | Cardiovascular abnormalities and dysfunction related to the onset of heart disease Increased blood pressure and anxiety | Car use can also affect pedestrian safety, with motor vehicle-related injuries continuing to disproportionately affect those without access to a vehicle, such as poor, young and older adults [77,78]. Gatersleben and Uzzell [79] characterised passive modes of transportation, such as by car or public transportation, as being more stressful and boring. Lyons and Chatterjee [80] reported that the effects of long commutes, such as fatigue and chronic stress, can induce cardiovascular abnormalities and dysfunction related to the onset of heart disease. Moreover, Frank et al. [70] (p. 1) identified “each additional hour spent in a car per day was associated with a 6% increase in the likelihood of obesity. Longer commuting times reportedly; makes people more tired” [81]; can result in reduced sleep time [82]; can increase blood pressure [83] and anxiety [84]; and can negatively affect life satisfaction, stress, and family life [84,85]. |

| Noise | Nuisances can lead to sleep deprivation. | Various mental health and physical health symptoms | The UK’s Royal Commission on Environmental population reported [86] that excessive and persistent noise may lead to poor mental health due to sleep disturbances and annoyance. Additionally, the Scottish Government [87] stated that noise-related problems can be more prevalent in areas of socioeconomic disadvantage. Likewise, a nationwide Danish study [88], among individuals living in multi-story housing, identified neighbourhood noise annoyance as being associated with various mental and physical health symptoms. |

| Air pollution | Air pollution can result in exposure to NOx and SO2 pollutants. | Exposure associated with diabetes and neurological diseases connected to lower levels of happiness and poor mental health. Air pollutants have also been associated with incidence of Parkinson’s disease and non-Alzheimer’s dementia. | The UK Green Building Council [89] identified that air pollution is associated with diabetes and neurological diseases and can affect time of pregnancy and birth weight. The UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs [90] linked air pollution not only to cancer, but also to stroke and heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and changes linked to dementia. It added that the health effects of air pollution disproportionately affect older adults, children, and those with existing respiratory conditions (ibid.). Moreover, air pollutants have also been associated with incidence of Parkinson’s disease and non-Alzheimer’s dementia [91]. Sustrans [92], the UK walking and cycling charity, concluded that air pollution can contribute to greater health inequalities in deprived communities, because they are more likely to be located near busy roads rather than secluded streets. Air pollution both real and perceived have also been reported [93,94] to affect mental health and as being connected to lower levels of happiness. |

| Housing | Many housing factors can affect mental and physical health, such as, but not limited to, dampness, noise, lighting, air quality, tenure and design. | Association between large building types and negative social relations leading to decreased social cohesion, neighbourliness and social capital compared to single-unit housing. | Many aspects of housing were reported by Macdonald and Thompson [95], as affecting both mental and physical health, such as dampness, noise, lighting, air quality, tenure, and design. King [96] found an association between large building types and negative social relations, (including social cohesion, social capital, and neighbourliness) in contrast to single-unit housing. Other studies [97,98,99] suggested several symptoms for sick building syndromes, affecting different parts of the human body, ranging from headache, fatigue, and irritation in upper respiratory tract to nose, throat, eyes, and dermal abnormalities. Ghaffarianhoseini et al. [15] categorised these symptoms into eight main groups: respiratory, nasal, ocular, oropharyngeal, cutaneous, lethargy, cognitive and general. |

| Insufficient drainage and buffer capacity | The accumulation of local rainfall runoff due to insufficient drainage and buffer capacity leading to flooding. | Threats to physical health (mortality) and poor mental health. Survivors can suffer psychosocial effects such as distress, anxiety, pain and depression | Alderman et al. [100] catalogued how the accumulation of local rainfall runoff due to insufficient drainage and buffer capacity can result in flooding threatening physical health (mortality) and contributing to poor mental health due to flooding threats. Foudi et al. [101] found that survivors can suffer psycho-social effects such as distress, anxiety, pain, depression, and social dysfunctions. |

| UNS: Perceived Physical Environment Factors | |||

| Perceived Physical Environment Factors | Effects | Outcomes | Identified Symptoms Associated with UNS |

| Crowdedness | Can lead to feeling that people are too close | Correlated negatively with quality of life | Crowding cannot be defined objectively [102], but rather is a perceived state of mind and the feeling of other people being too close. Crowdedness needs to be distinguished from density, as it has no inherent positive or negative connotations, but the former does. Gray [102] defined over-crowdedness as a perceived level of density that has a detrimental effect on psychological and mental wellbeing. McCrea, Shyy and Stimson [103] agreed that perceived crowdedness correlated negatively with quality of life. |

| Accessibility | A perception that destinations are not accessible (e.g., by walking, cycling or by mobility assisted devices) | Effect on subjective wellbeing | McCrea, Shyy and Stimson [103] found that perceived accessibility to goods and services influenced subjective wellbeing, while actual proximity was shown to have little or no effect. Lättman et al. [104] reported that, over time, perceived accessibility (or lack of this) has been linked to life satisfaction. |

| Greenness | A lack of perceived access to greenspace or trees can lead to avoidance of public realm, decreased social interaction and physical activity. | Effect on subjective wellbeing | Bjornstrom and Ralston [105] stated that a high prevalence of trees in a neighbourhood can lead to it being perceived as dangerous, resulting in a decrease in social cohesion. |

| Aesthetics, and Physical appearance | A perceived lack of aesthetic beauty (e.g., tall building heights, poorly maintained streets, parks and buildings). | Negative effect on restorative potential More likely to experience lower levels of mental wellbeing. | Lindal and Harti [106] stated that building heights had a negative effect on restorative potential, defined by Scopelliti, Carrus and Bonaiuto [107] as “the capacity for natural environments to replenish cognitive resources depleted by everyday activities and to reduce stress levels” (p. 1). Moreover, people who perceive their neighbourhoods to be dirty and poorly maintained have been identified as more likely to experience lower levels of mental wellbeing [108,109]. Such perceptions are disproportionately felt by older adults, women and the unemployed [50,110]. |

| Walkability | A perception that destinations are far to walk to can lead to lower levels of physical activity. | Cardiovascular disease, stroke and all-cause mortality. | Jun and Hur [111] suggested that, even in areas where physical walkability (proximity) is high, residents may walk less if they perceive their neighbourhood as unsafe for walking in. Therefore, they advised that future places should examine the unique relationship between the proximity and functions of public facilities with their urban contexts-the proximity of other community services to residences, and how linking isolated neighbourhoods (e.g., gated compounds) with other neighbourhoods would help in initiating the healthy lifestyles of citizens. |

| Eye-level experience | Ground floors that are “inactive” can promote feelings of insecurity through more coming and goings. | Inactive ground floors as contributing to sedentary lifestyles by making walking and biking less interesting, and so less enjoyable to the senses. | Karssenberg et al. [112] claimed although “the ground floor may be only 10% of a building but it determines 90% of the building’s contribution to [a person’s] experience of the environment” (p. 16). How a building meets the street, they maintained, can promote social isolation, limiting opportunities for social interaction. Ground floors that are “inactive” (without windows looking onto the street, no patio furniture, plants, artwork, etc.) can promote feelings of insecurity through more coming and goings (ibid.). Sim [38] (p. 83) described inactive ground floors as contributing to sedentary lifestyles by making walking and biking less interesting, and so less enjoyable to the senses. |

| Comfort and discomfort (Place Image) | Perceiving a built environment as uncomfortable can contribute to poor physical and mental health. | Poor physical health and mental wellbeing outcomes. | Perceiving a built environment as uncomfortable is held to lead to several undesirable behavioural decisions that can contribute to poor physical and mental health. Sim [38] (p. 272) explained that “human beings are highly sensitive to unpleasant physical and climatic phenomena. When there is an interruption or disconnect between one place and another because of a bad experience, patterns of behaviour are lost, and people are much less likely to walk or spend time in that place).” Discomfort and nuisances can manifest themselves in a variety of ways throughout the built environment: for example, poor or lack of public seating options in the public realm reduces opportunities to sit, watch and socialize [113]. Likewise, Corcoran and Marshall [114] suggested that, unless opportunities for macro social interactions are provided, social isolation and loneliness rises as people avoid the public realm. Zhang [115] held that element of the built environment that are perceived as uncomfortable depress use of alternatives to private vehicle. Uncomfortable or lack of seating at public transportation stops can decrease waiting, so depressing passenger levels. |

| UNS: Social Environment Factors | |||

| Social Environment Factors | Effects | Outcomes | Identified Symptoms Associated with UNS |

| Social Order and Social Cohesion | Low social order and social cohesion can lead to neighbourhood instability. Can increase levels of psychological distress stress. | Psychosis and depression | A lack of social cohesion in urban areas has been identified as contributing to psychosis and depression [116,117,118]. |

| Residential Stability | Residential instability can lead to chronic homelessness. Can increase levels of psychological distress stress. | Mortality and poor physical and mental health | People who are chronically homeless and do not have residential stability have higher morbidity, such as increased mortality and poor physical and mental health [119,120]. Persons who are not homeless, yet still face home instability, are more likely to experience poor health compared to people who have residential stability [121]. |

| Reduced social capital and social isolation | Low socio-economic status can lead to poor self-esteem, feelings of inferiority, frustration and hopelessness. Can increase levels of psychological distress stress. | Poor mental health | Gehl [122] argued that a low priority has been given to public space as a meeting place, because of the ideologies, such as modernism, that dominated planning and urban designer throughout the last half of the twentieth century. He held (p. 3) that the design of modern cities prioritizes communication and transportation infrastructure for industry over other considerations, contributing to inequality within urban environment, since “the traditional function of city space as a meeting place and social forum for city dwellers [was] reduced, threatened or phased out”. This is not a new observation. Ward [123] (p. 25) had already concluded, three decades previously, that cities had been built “deliberately for one particular kind of citizen: adult, male, white collar, out of town car-user”. Zeiher [124] (p. 66) noted that cities designed with an emphasis on vehicular traffic intensify a process of “insurlarisation”, creating a growing separation between places built to meet people’s needs. Christensen and O’Brien [125] (p. 7) agreed, suggesting that, for some adults, if walking between their “islands of activity, is too dangerous or too far to commute, then driving is the preferred option”. However, driving is a luxury available only to those who can afford and choose to drive. This rationing by price has led to an increase in social isolation and reduced social capital between neighbourhood residents. This has, in turn, led to reductions in social capital which, they reported, can be disproportionately felt by older adults and young children, especially within age-segregated neighbourhoods. |

| Intergenerational segregation | Urban life has become increasingly isolated and segregated. | Increase anxiety. Poor mental health and physical health increase levels of psychological distress stress. | Manchester and Facer [126] identified that over the last two decades, interaction between generations in public spaces has diminished: positive contact have reduced as children and older adults alike are encouraged to live and spend time in age-segregated spaces where physical barriers such as gates and high walls predominate. They reported that fear and competition over resources and policies have also contributed to our cities becoming increasingly segregated on generational lines (p. 5). Vanderbeck and Worth [127] (p. 4) argued that intergenerational segregation results from patterns of design that “have contributed to the production of spaces-such as city centres-that can prove relatively inaccessible or unwelcoming to people of particular life stages”. van Vliet [128] (p. 349) described how, since young children and older adults are not workers in most Western market-based economies, their needs are often overlooked. Without being part of the workforce, both groups “cannot translate their needs into a market demand”. Wu and Chan [129] (p. 2) agreed, noting that accordingly, older adults “tend to travel outside their own neighbourhoods less often than do younger adults”. As both older adults and children can experience restricted mobility, participating in social interactions can become difficult for them [130,131]. They reported that, by overlooking the needs of older adults and young children in particular, urban life has become increasingly isolated and segregated. |

| UNS: Perceived Social Environment Factors | |||

| Perceived Social Environment Factors | Effects | Outcomes | Identified Symptoms Associated with UNS |

| Perceived Safety | A perceived threat to safety can lead to lower levels of physical activity and dissuade certain groups (e.g., women) from physical exercise and can increase levels of psychological distress stress. | Poor mental health and physical health | A growing body of literature reporting public health research suggests that perceived neighbourhood safety is linked to health outcomes [132,133,134]. For example, Hale [135] linked perceived threats to safety to lower levels of physical activity. Bjornstrom and Ralston [105] (p. 45) demonstrated that “perceived danger and concentrated disadvantage have strong negative correlations with perceived cohesion, regardless of the built environment objective characteristics”. Negative perceptions of a neighbourhood’s safety have been associated with anxiety, poor health outcomes [136] and poor self-rated health [133]. Additionally, feeling unsafe within a neighbourhood can contribute to people (particularly women in low-income neighbourhoods) not using the built and natural environment for exercise [137,138]. |

| Neighbourhood Satisfaction | A lack of neighbourhood satisfaction; residents in their neighbourhood can have an effect on physical activity within the neighbourhood and can increase levels of psychological distress stress. | Lower physical activity and self-rated health | Stronegger et al. [139] reported that neighbourhood satisfaction can have an effect on physical activity and self-rated health. Stokols and Shumaker [140] attested that, without an attachment to place, people experience higher stress levels and more health problems. |

| Place Attachment (sense of place), Identity and familiarity | An absence of place attachment can increase levels of psychological distress stress. A lack of control to influence local environment can increase levels of psychological distress stress. | Poor mental health | Stokols and Shumaker [140] attested that, without an attachment to place, people experience higher stress levels and more health problems. Karssenberg et al. [112] noted that a lack of neighbourhood activities such as local markets and events can also contribute to a perceived diminished local identity. Similarly, they suggested that neighbourhoods with places with blank or uninteresting facades can contribute to a perceived lack of neighbourhood identity. |

| Social Status | A person’s perceived low standing or importance in relation to other people within a society can increase levels of psychological distress stress. | Depression. Cardiovascular disease and immune function | A person’s perception that they have low social status (relative to the perceived standing or importance in relation of other people within a social group) can have a range of associated effects: depression [141], cardiovascular disease [142], and immune malfunction [143]. |

| Key Physical Health & Mental Wellbeing Detracting Qualities at the Neighbourhood Level | Cardio-Vascular Disease, Type-2 Diabetes | Poor Diet & Food Poverty | Several Forms of Cancer | Respiratory Illnesses | Poor Mental Health | Vehicle Related Accidents | Relevant Urban Design Criteria to Mitigate UNS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POOR AIR QUALITY |  |  |  |  |  | Limiting emissions and sufficient distance of receptors through increased gross density encouraging active public transportation | |

| LITTLE OR NO ACCESS TO NATURE |  |  |  |  |  | Location and network of greenspace relative to homes and workplaces | |

| LOW PARTICIPATION IN PUBLIC LIFE |  |  | Attractive all-age friendly design of walkable public realm. Active facades and gradual transition between public and private space. Inclusive and equitable planning and design processes. | ||||

| FEELING UNSAFE & UNCOMFORTABLE |  |  |  | Safe, well-lit, sociable space, child-friendliness and low traffic speeds. | |||

| LIVING SOMEWHERE UNHEALTHY |  |  |  |  |  |  | Active travel and walkable access to daily needs, including healthy food options and primary schools. |

| LIMITED PEACE & TRANQULITY |  |  | Access to peaceful places and distance from sources of pollution caused by noise and light. | ||||

| OBESOGENIC LIFESTYLE |  |  |  |  |  | Quality public spaces, safe walking routes, connected green spaces and minimal sprawl. | |

| LITTLE (OR NO) SENSE OF CONTROL & IDENTITY |  | Flexible urban space that allows for neighbourhood modification and personalization to express neighbourhood identity. |

PRIMARY EFFECT.

PRIMARY EFFECT.  SECONDARY EFFECT.

SECONDARY EFFECT.Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

AlWaer, H.; Speedie, J.; Cooper, I. Unhealthy Neighbourhood “Syndrome”: A Useful Label for Analysing and Providing Advice on Urban Design Decision-Making? Sustainability 2021, 13, 6232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116232

AlWaer H, Speedie J, Cooper I. Unhealthy Neighbourhood “Syndrome”: A Useful Label for Analysing and Providing Advice on Urban Design Decision-Making? Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116232

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlWaer, Husam, Joshua Speedie, and Ian Cooper. 2021. "Unhealthy Neighbourhood “Syndrome”: A Useful Label for Analysing and Providing Advice on Urban Design Decision-Making?" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116232

APA StyleAlWaer, H., Speedie, J., & Cooper, I. (2021). Unhealthy Neighbourhood “Syndrome”: A Useful Label for Analysing and Providing Advice on Urban Design Decision-Making? Sustainability, 13(11), 6232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116232