Implicating Human Values for designing a Digital Government Collaborative Platform for Environmental Issues: A Value Sensitive Design Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Context and Literature

2.1. Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and Environmental Sustainability

2.2. E-Government

2.2.1. E-Government for Environmental Sustainability

2.2.2. Digital Government Collaborative Platforms for E-government Services

2.3. Human Values

2.3.1. Human Values and Environmentally Responsible Behavior

2.3.2. Human Values and E-Government Design

3. Values-Sensitive Design of ICT

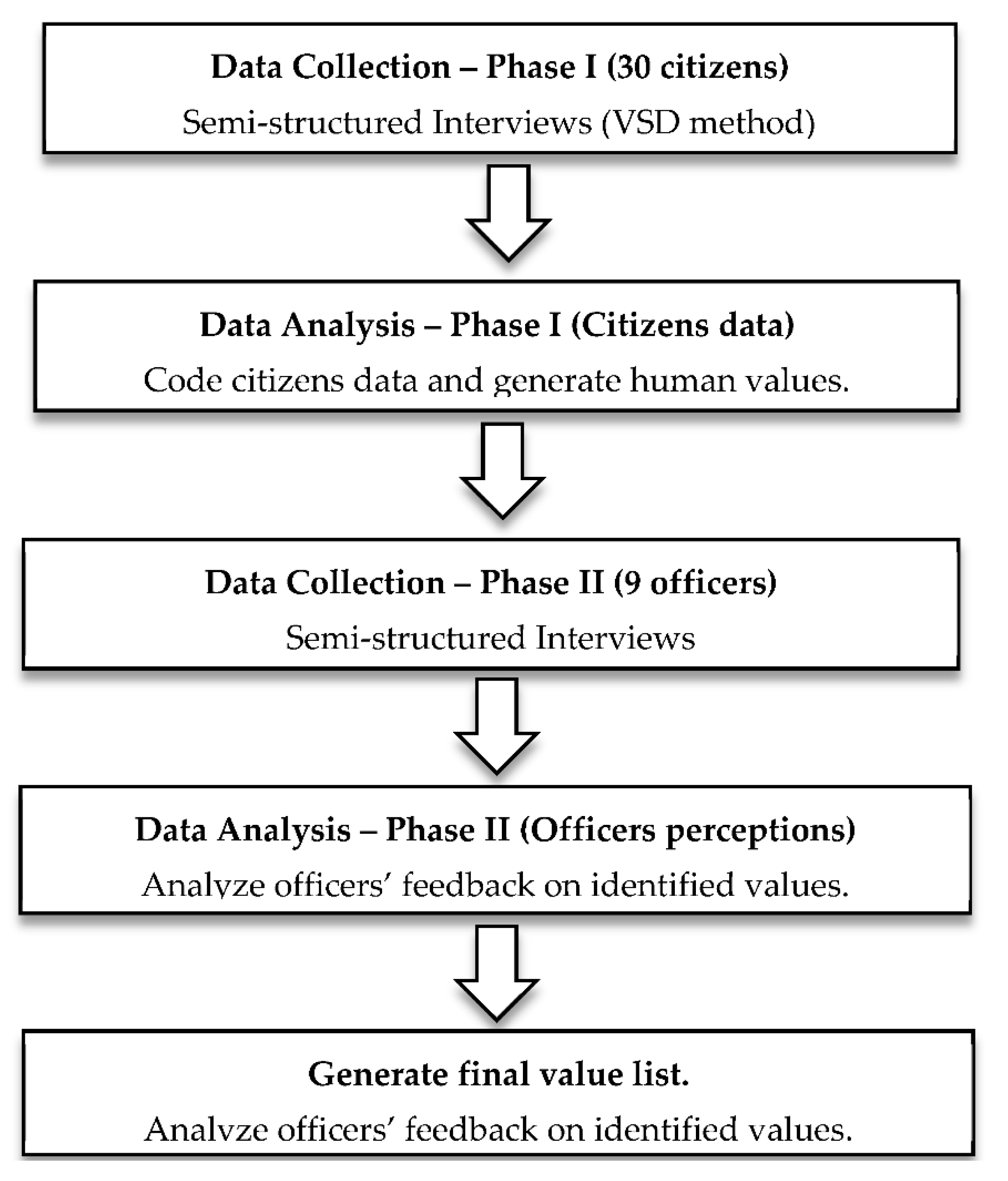

4. Research Method

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Data Analysis

5. The Results

5.1. Citizens’ Values

5.2. Officers’ Value

5.3. System Features

6. Discussion

6.1. Research Contributions

6.2. Research Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Questions

- Level 1: Demographic Information (Gender, age, and education)

- Level 2: Proposed Digital Government Collaborative Platform

- What do you think about introducing a ‘Digital Government Collaborative Platform’ (IT-based) to communicate with the relevant government authorities in addressing environmental issues (Government endorsed)?

- If we introduce a Digital Government Collaborative Platform, as a Citizen, how can you contribute?

- What are looking for in such a platform?

- How can such a platform contribute to environmental problems?

- Do you think such platform can reduce/solve environmental issues?

- Level 3: Values

- What motivates you to involve in environmental protection activities? (Why do you think ‘Environmental Protection’ is essential for us?

- As per your understanding, what is important to you (‘Values’) in such a ‘Digital Government Collaborative Platform’ to address environmental issues?

- What are the Identified as obstacles or suggestions to solve environmental issues?

- What do you like/do not like in existing e-government systems?

Appendix B

| Values Statements Derived from the Interview with Citizens | Identified Value | Value Category | Value Implicated in DGCP Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| “We would like to see, how the concerns raised are processed. It should not be just a mere system to store the concerns.” | Internal process flow should be visible to the citizens. | Transparency | Provide access to internal processes feature—Citizens are provided access to login and track the details of the process flow. |

| “Many ordinary people are in fear that sometimes if they raise a concern, later on, it will be backfired to them.” “The system should ensure that it safeguards people’s personal opinions after they made the concern or complaint.” | Ensure the personal safety of the citizens. | Safety | Protecting privacy of the citizens feature—System will keep the profile information of the citizen confidentially and it will be disclosed only when required with the permission of citizen. |

| “It should be very user friendly and able to access in many languages. We need to think about majority as well as minority during the system design.” | Ability to use the platform in many languages. | Universal Usability /Comprehensibility | Multi-language access—User can select the preferred language to use the system. |

| “Sometimes when we submit a query, we never know what happens. In this system, if we can implement to whom we are reporting, and actions taken by them is important to know.“ | Increase the two-way communication. | Feedback | Track the status of the query (or similar) feature—Citizens are always provided a feedback, regular updates, access to track the changes in addition to acknowledgement. |

| “We are in a digital era with overwhelming information have been shared and we are clueless to differentiate real news vs. fake news.” | Accuracy and integrity of the information shared in the platform. | Authenticity | Validate the information feature—Information communicated (input/output) is well validated to identify the real vs. fake information. |

| “The government decisions should solely base on the pure intention of developing the country and not for their political advantageous and personal benefits.” | Assurance of fair solutions for the citizen concerns. | Fairness (Free from bias) | Reply and comment feature—For the concerns raised, officers are supposed to provide a reply with evidence. Citizens can comment, like/dislike or ask for further information. |

| “Citizens should be empowered through this platform and this platform serves as a way to raise voice for the voiceless.“ | A citizen with a least digital literacy can access the system | Representativeness/Democracy | Simple Graphical User Interfaces (GUI) and process flow feature—Any novice user can follow a few basic steps to interact in the system. |

| “We have seen the conflicts and mismatch in the ideas between politicians and officers and among government and citizens. But citizens expect a rationale for the action taken by the government.” | Justification for the validity of the information shared. | Accountability | React, comment, and reply feature—Both citizens and officers can like, dislike, or further comment and request for the further information if they dissatisfied with the provided information. |

| “We have experienced and heard about the politicians and other officers influence to execute their own agenda through their political power. There is no point of systems if it is not independent from such influence.” | Actions are taken according to the counties existing law, policies, and procedures. | Legitimacy | Accessibility to the authority’s policies, procedures, and legal aspects—Users can access the internal but information where the public have right to access. |

| “When we report certain environmental related issues to authorities including police, perhaps they will disclose the details of the person who raised the concern.” | Focus on the issue and its impact than the person who raised the concern. | Informed Consent | Control to the personal Information sharing feature—Users can control the visibility of their personal information in the platform. |

| “Without making us confuse, we are looking for detailed information for ourselves to make more accurate decisions towards problems and propose our own ideas and solutions.” | Availability of information much as possible to make decisions. | Autonomy | Making access for information feature—Most of the information is available to access. |

| “Other than a few of a web sites to provide some basic environmental information, we need more interactive platforms to bi-directional communication and information retrieval.” | Assistance to find required information easily. | Awareness | Interactive information sharing feature—Automated information request and reply ability to retrieve to find required information. |

| “Social work has become trending among young generation and it is easy to gather people specially for env. conservation” | Gather other citizens with similar interest. | Human Welfare | Crowdsourcing feature—Citizens can propose new ideas and gather others to making them to actions. |

| “There are some env. issues where we can find and provide simple solutions, only thing is we are not motivated enough to act.” | Motivate others to engage and making them aware of simple solutions. | Attitude | Share and propose feature—Share what they have seen worthy for other and propose new solutions. |

| “Government should ensure that reported concerns are taken into the consideration as top priority and they are dedicated to find fair solutions.” | Possible to provide fair solution within a short time frame. | Trust | Reporting to different levels feature—If the user does not receive a reply (or satisfied reply) it can be forwarded to high level officer |

References

- Han, J. Can Urban Sprawl Be the Cause of Environmental Deterioration ? Based on the Provincial Panel Data in China. Environ. Res. 2020, 189, 109954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathaniel, S.P.; Nuwulu, N.; Bekun, F. Natural Resource, Globalization, Urbanization, Human Capital, and Environmental Degradation in Latin American and Caribbean Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 6207–6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissanayake, D.; Tilt, C.; Xydias-Lobo, M. Sustainability Reporting by Publicly Listed Companies in Sri Lanka. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Escalating Chronic Kidney Diseases of Multi-Factorial Origin in Sri Lanka: Causes, Solutions, and Recommendations. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2014, 19, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ranaraja, C.D.M.O.; Arachchige, U.S.P.R.; Rasenthiran, K. Environmental Pollution and Its Challenges in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2019, 8, 417–419. [Google Scholar]

- Maheshi, D.; Steven, V.P.; Karel, V.A. Resources, Conservation and Recycling Environmental and Economic Assessment of ‘Open Waste Dump’ Mining in Sri Lanka. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 102, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasimli, O.; ul Haq, I.; Gamage, S.K.N.; Shihadeh, F.; Rajapakshe, P.S.K.; Shafiq, M. Energy, Trade, Urbanization and Environmental Degradation Nexus in Sri Lanka: Bounds Testing Approach. Energies 2019, 12, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Owen, R.P.; Parker, A.J. Citizen Science in Environmental Protection Agencies. Citiz. Sci. 2019, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Boas, I.; Mol, A.P.J.; Lu, Y. E-Participation for Environmental Sustainability in Transitional Urban China. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hards, S. Social Practice and the Evolution of Personal Environmental Values. Environ. Values 2011, 20, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hards, S. Geoforum Tales of Transformation: The Potential of a Narrative Approach to pro-Environmental Practices. Geoforum 2012, 43, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Community Action: A Neglected Site of Innovation for Sustainable Development? In Politics of Sustainable Development: Theory, Policy and Practice Within the European Union; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2006; pp. 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Sapraz, M.; Han, S. Improving Collaboration Between Government and Citizens for Environmental Issues: Lessons Learned from a Case in Sri Lanka. In ICT Systems and Sustainability. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Tuba, M., Akashe, S., Joshi, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 1270, pp. 297–306. ISBN 978-981-15-8289-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973; ISBN 0029267501. [Google Scholar]

- Palacin, V.; Angela, M.; Hsieh, G.; Knutas, A.; Wolff, A. Human Values and Digital Citizen Science Interactions. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2021, 149, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufi, B.; Maguire, M.; Building, H.; Way, H.; Soufi, B.; Maguire, M. Achieving Usability Within E-Government Web Sites Illustrated by a Case Study. In Symposium on Human Interface and the Management of Information; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 777–784. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Bretschneider, S.; Gant, J. Evaluating Web-Based E-Government Services with a Citizen-Centric Approach. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2005; p. 129b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Nusir, M. Co-Design for Government Service Stakeholders. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017; pp. 2539–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winkler, T.; Spiekermann-hoff, S. Human Values as the Basis for Sustainable Information System Design. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2020, 38, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.; Hendry, D.G. Value Sensitive Design: Shaping Technology with Moral Imagination; Kindle Edition; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2019; ISBN 9780262351683. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, B.; Borning, A.; Davis, J.L.; Gill, B.T.; Kahn, P.H.; Kriplean, T.; Lin, P. Laying the Foundations for Public Participation and Value Advocacy: Interaction Design for a Large Scale Urban Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Digital Government Research, Montreal, QC, Canada, 18–21 May 2008; pp. 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; United Nations Digital Library, United Nations, 1987; Volume 42, Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/139811?ln=en (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development, United Nations, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Athukorala, W.; Karunarathna, M. Environmental Challenges and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Study about the Emerging Environmental Issues in Sri Lanka. Appl. Econ. Bus. 2018, 2, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Emas, R. The Concept of Sustainable Development: Definition and Defining Principles. Brief GSDR 2015, 2015, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Howes, M.; Wortley, L.; Potts, R.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Serrao-Neumann, S.; Davidson, J.; Smith, T.; Nunn, P. Environmental Sustainability: A Case of Policy Implementation Failure? Sustainability 2017, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahid, H.; Din, B.H. Determinants of Intention to Adopt E-Government Services in Pakistan: An Imperative for Sustainable Development. Resources 2019, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehman, K.; Shah, A.A.; Ahmed, K. E-Government Identification to Accomplish Sustainable Development Goals (UN 2030 Agenda) A Case Study of Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), San Jose, CA, USA, 18–21 October 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.H.; Razali, R.; Nasrudin, M.F. Key Factors for E-Government towards Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 2864–2876. [Google Scholar]

- E-Government. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/about/unegovdd-framework (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Homburg, V. ICT, E-Government and E-Governance: Bits & Bytes for Public Administration. Palgrave Handb. Public Adm. Manag. Eur. 2017, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Pan, L.; Lei, Y. What Is the Role of New Generation of ICTs in Transforming Government Operation and Redefining State-Citizen Relationship in the Last Decade? In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Melbourne, Australia, 3–5 April 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.V.; Cunha, M.A.; Lampoltshammer, T.J.; Parycek, P.; Testa, M.G.; Viale, G.; Cunha, M.A.; Lampoltshammer, T.J. Information Technology for Development Increasing Collaboration and Participation in Smart City Governance: A Cross-Case Analysis of Smart City Initiatives. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2017, 23, 526–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. E-Government Survey 2020: Digital Government in the Decade of Action for Sustainable Development; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, 2020; Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/en/Research/UN-e-Government-Surveys (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Deng, H.; Karunasena, K. Evaluating the Performance of E-Government in Developing Countries. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.T. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and Environmental Sustainability in Developed and Developing Countries. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2018, 12, 758–783. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova, I.; Vorotnikov, A.; Doronin, N. The Potential of Digital Platforms for Sustainable Development Using the Example of the Arctic Digital Platform 2035. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Sapraz, M.; Han, S. A Review of Electronic Government for Environmental Sustainability. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Xi’an, China, 8–12 July 2019; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2019/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Digital Participatory Platforms for Co-Production in Urban Development: A Systematic Review. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2018, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Millard, J. ICT-Enabled Public Sector Innovation: Trends and Prospects. In Proceedings of the ICEGOV2013; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, S.A.; Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Sandoval-Almazán, R. Collaborative E-Government. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2012, 6, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bertot, J.C.; Jaeger, P.T.; Munson, S.; Glaisyer, T. Social Media Technology and Government Transparency. Computer 2010, 43, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertot, J.C.; Jaeger, P.T.; Grimes, J.M. Promoting Transparency and Accountability through ICTs, Social Media, and Collaborative e-Government. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2012, 6, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceron, A.; Negri, F. The “Social Side” of Public Policy: Monitoring Online Public Opinion and Its Mobilization During the Policy Cycle. Policy Internet 2016, 8, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel, E.; Manning, C.; Scott, B.; Koger, S. Ecosystem Conservation. Science 2017, 279, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.; Dietz, T. The Value Basis of Environmental Psychology. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudsepp, M. Values and Environmentalism. TRAMES J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2001, 5, 211. [Google Scholar]

- Earth Charter International The Earth Charter. 2013. Available online: https://earthcharter.org/read-the-earth-charter/ (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Simonofski, A.; Chantillon, M.; Crompvoets, J.; Vanderose, B.; Snoeck, M. The Influence of Public Values on User Participation in E-Government: An Exploratory Study. In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaiian Conference on Information Systems Sciences (HICSS), Maui, HI, USA, 8–10 January 2020; Volume 3, pp. 2103–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Twizeyimana, J.D.; Andersson, A. The Public Value of E-Government–A Literature Review. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberg, J.; Shahmehri, N. An Empirical Study of Human Web Assistants: Implications for User Support in Web Information Systems. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 31 March–5 April 2001; pp. 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephanidis, C. User Interfaces for All: New Perspectives into Human-Computer Interaction. User Interfaces All Concepts Methods Tools 2001, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, B. Bias in Computer Systems. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 1996, 14, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.; Gong, L. Speech Interfaces. Commun. ACM 2000, 43, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B. The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places; Cambridge University Press, CSLI (Center for the Study of Language and Information): Stanford, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, B. “It’s the Computer’s Reasoning About Computers Fault”- as Moral Agents. Comput. Sci. 1995, 226–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.; Felten, E.; Millett, L.I. Informed Consent Online: A Conceptual Model and Design Principles. Univ. Wash. Comput. Sci. Eng. Tech. Rep. 2000, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, B. Social Judgments and Technological Innovation: Adolescents’ Understanding of Property, Privacy, and Electronic Information. Comput. Hum. Behav. 1997, 13, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, E.A.; Tang, J.C.; Morris, T. Piazza: A Desktop Environment Supporting Impromptu and Planned Interactions. In Proceedings of the 1996 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Boston, MA, USA, 16–20 November 1996; pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.; Hall, M.G.; Kahn, P.H.; Hagman, J.; Hall, M.G. Hardware Companions ?–What Online AIBO Discussion Forums Reveal about the Human-Robotic Relationship. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 5–10 April 2003; pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesson, N. Software Safety in Embedded Computer Systems. Commun. ACM 1991, 34, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, F.N. “Trust Me, I’m an Online Vendor”: Towards a Model of Trust for E-Commerce System Design. In Proceedings of the CHI’00 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, The Hague, The Netherlands, 1–6 April 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nissnebaum, H. Securing Trust Online: Wisdom or Oxymoron? BUL Rev. 2001, 81, 101–131. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, B.; Kahn, P.H.; Alan, B. Value Sensitive Design and Information Systems. Handb. Inf. Comput. Ethics 2009, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, P.; Friedman, B. Human Values, Ethics, and Design. In The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 1241–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, B. Value-Sensitive Design. Interactions 1996, 3, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borning, A.; Friedman, B.; Davis, J.; Lin, P. Informing Public Deliberation: Value Sensitive Design of Indicators for a Large-Scale Urban Simulation. In Proceedings of the ECSCW 2005, Ninth European Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work, Paris, France, 18–22 September 2005; pp. 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, P.; Boring, A. A Case Study in Digital Government: Developing and Applying UrbanSim, a System for Simulating Urban Land Use, Transportation, and Environmental Impacts. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2004, 22, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Czeskis, A.; Dermendjieva, I.; Yapit, H.; Borning, A. Parenting from the Pocket: Value Tensions and Technical Directions for Secure and Private Parent-Teen Mobile Safety Categories and Subject Descriptors Parenting Technologies for Teens. In Proceedings of the 6th Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security, Microsoft in Redmond, Washington, DC, USA, 14–16 July 2010; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; Hagman, J.; Severson, R.L. The Watcher and the Watched: Social Judgments About Privacy in a Public Place. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2006, 21, 235–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, P.H.; Friedman, B.; Pérez-granados, D.R.; Freier, N.G. Robotic Pets in the Lives of Preschool Children. Interact. Stud. 2006, 3, 405–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freier, N.G. Children Attribute Moral Standing to a Personified Agent. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Florence, Italy, 5–10 May 2008; pp. 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dadgar, M.; Joshi, K.D. The Role of Information and Communication Technology in Self-Management of Chronic Diseases: An Empirical Investigation through Value Sensitive Design. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2018, 19, 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.; Kahn, P.H.; Hagman, J.; Severson, R.L. Coding Manual for “The Watcher and The Watched: Social Judgments about Privacy in a Public Place”. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2005, 21, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hemachandra, S.V. ‘Butterflies Taking down Giants’ 1: The Impact of Facebook on Regime Transformation in Sri Lanka. South Asianist J. 2017, 5, 366–390. [Google Scholar]

- van de Poel, I. Translating Values into Design Requirements. Philos. Eng. Reflect. Pract. Princ. Process 2013, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Beyond Technology: Identifying Local Government Challenges for Using Digital Platforms for Citizen Engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuenfschilling, L.; Truffer, B. The Structuration of Socio-Technical Regimes-Conceptual Foundations from Institutional Theory. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubham; Charan, P.; Murty, L.S. Organizational Adoption of Sustainable Manufacturing Practices in India: Integrating Institutional Theory and Corporate Environmental Responsibility. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effah, J.; Nuhu, H. Institutional Barriers to Digitalization of Government Budgeting in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Ghana. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2017, 82, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hwang, K.; Choi, M. Effects of Innovation-Supportive Culture and Organizational Citizenship Behavior on e-Government Information System Security Stemming from Mimetic Isomorphism. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawar, S.A.; Kauppi, K. Understanding the Adoption of Socially Responsible Supplier Development Practices Using Institutional Theory: Dairy Supply Chains in India. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2018, 24, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Reuver, M.; van Wynsberghe, A.; Janssen, M.; van de Poel, I. Digital Platforms and Responsible Innovation: Expanding Value Sensitive Design to Overcome Ontological Uncertainty. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2020, 22, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Human Values | Definition (Related to E-Government Design) | Sample Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Usability /Comprehensibility | The IS solution is available and easy to use by any of the citizens of the country willing to contribute to environmental sustainability. | “An Empirical Study of Human Web Assistants: Implications for User Support in Web Information Systems” [56] “User Interfaces for All: New Perspectives into Human–Computer Interaction” [57] |

| Fairness (Free from bias) | The information communicated in the platform is solely handled with the intention of making the world a safer and better place to live. | “Bias in Computer Systems” [58] “Speech interfaces from an evolutionary perspective” [59] |

| Accountability | Citizens and the government are responsible for providing reasons (or justification) for the request and responses in the platform. | “The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places” [60] “It’s the Computer’s Reasoning About Computers Fault”-as Moral Agents” [61] |

| Informed Consent | Citizens provide/share some sensitive information and expect to obtain permission for further processing. | “Informed Consent Online: A Conceptual Model and Design Principles” [62] |

| Autonomy | Ability to make an accurate judgement and to act without reacting to fake and trending news. | “Social judgments and technological innovation: adolescents understanding of property, privacy, and electronic information.” [63] “Piazza: a desktop environment supporting impromptu and planned interactions.” [64] |

| Human Welfare | Most of the citizens are eager to make green and eco-friendly environments pivotal in building quality life. | “What Online AIBO Discussion Forums Reveal about the Human–Robotic Relationship” [65], “Software Safety in Embedded Computer Systems” [66] |

| Trust | Citizens are expected to witness better results and active government engagement in the IS platform. | “Trust me, I’m an online vendor”: towards a model of trust for e-commerce system design” [67] “Securing trust online: wisdom or oxymoron” [68] |

| Description | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 56% |

| Female | 44% | |

| Age | 18–25 | 10% |

| 26–33 | 23% | |

| 34–41 | 20% | |

| 42–48 | 17% | |

| 49–55 | 13% | |

| 56–64 | 17% | |

| Education | High School | 23% |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 50% | |

| Master’s Degree | 20% | |

| Doctorate | 7% | |

| Department/Authority | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Central Environmental Authority (CEA) | 2 |

| Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) | 1 |

| Department of Forest Conservation (DFC) | 2 |

| Waste Management Authority, Western Province | 1 |

| National Cleaner Production Centre | 1 |

| Environmental Ministry | 2 |

| Coast Conservation Department | 1 |

| Value Statements Derived from the Interview with Citizens | Identified Value | Value Category | Value Implicated in DGCP Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| “We would like to see how the concerns raised are processed. It should not be just a mere system to store concerns”. | The internal process flow should be visible to the citizens. | Transparency | Provide access to internal processes feature- Citizens are provided access to login and track process flow details. |

| “Many ordinary people are in fear that sometimes if they raise a concern, later on, it will backfire on them”. “The system should ensure that it safeguards people’s personal opinions after they make the concern or complaint.” | Ensure personal safety of citizens. | Safety | Protecting the privacy of the citizens’ feature–The system will keep the profile information of the citizen confidentially, and it will be disclosed only when required with the permission of the citizen. |

| Value Category | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Transparency (Derived from the study) | Opposite of Blackbox and related to truthfulness. All stakeholders must share accurate information. | “It will be great if we can see the actions taken by authorities to the queries submitted by the citizens through the system.” |

| Safety (Derived from the study) | Protect the personal safety of the stakeholders | “Sometimes, when your identity is tracked, sometimes you feel that you will get certain threats. Therefore, anonymity must be there as an option. For some sensitive topics or environmental issues, people may think twice about sharing their information. Therefore, the choice must be provided-for those willing to share information, to be supplied with the relevant accessibility and for those who would prefer to interact anonymously, to be allowed that option.” |

| Universal Usability /Comprehensibility (Derived from the study, also found in [20]) | The quality of being easy or possible to understand | “Always better to allow as many people as possible to contribute to the system. Sri Lanka is a multi-cultural country, and everyone must be able to use their language and contribute through this platform.” “Person like me I have many things in my head, a lot of things to care, in the meantime, if it is complex and not simple, I prefer not to use the same system again.” |

| Feedback (Derived from the study) | Citizens prefer to receive a detailed response without being limited to an acknowledgement | “What I believe as the key here is, citizens should get feedback, and it should be provided efficiently (time is taken to respond). We need somebody dedicated to handling these queries. Moreover, when the concern is raised, the thread should be followed until we get a reasonable solution.” |

| Authenticity (Derived from the study) | The quality of the information shared by users–level of accuracy/ credibility | “As a user, we are so confused about the information circulated on social media platforms. Some of them are manipulated and altered. It is not only fake news, but we can also find fake profiles, which are misleading and can cause unrest among people.” |

| Fairness (Free from bias) (Derived from the study, also found in [20]) | Not just acknowledging the citizens’ concern, it must be legally considered, and the solution must be provided without any prejudice. | “We have experienced and generally believe that in carrying out duties, certain public officers are biased in decision making due to personal gain, or they may not be able to carry out their duties due to the influence of politicians. There is no point in such a system if such politicians influence it or if the officers do not carry out assigned job tasks according to rules and regulations.” |

| Representativeness/Democracy (Derived from the study) | Support for a democratic society (Input of many stakeholders’ views) | “There are instances where especially environmentalists’ and citizens’ comments, advise, and voice is disregarded sometimes in development projects carried out in the country.” |

| Accountability (Derived from the study, also found in [20]) | Citizens and government must justify their arguments-the fact of being responsible for one’s actions and being able to provide satisfactory reasons for it, or the degree to which this happens. | “Before politicians come to power, they provide lots of promises, but after coming into power they pursue personal agendas. They always support their close relatives, friends, and known people. After coming into power, they never listen to the public, and so the people lose their voice and agency.” |

| Legitimacy (Derived from the study) | The fact of being allowed by law or done according to the rules of an organization or activity. | “I would reluctantly say that how the government officers and politicians handle certain issues are not acceptable, and people have lost trust towards decision making.” |

| Informed Consent (Derived from the study, also found in [20]) | Obtain permission to use specific confidential data. | “Once we provide data/information, it must be kept safe, and only the relevant authorities must be able to access the system.” |

| Autonomy (Derived from the study, also found in [20]) | The independence to make decisions without the influence of others | “We cannot always depend on the government to provide solutions; we as citizens should be able to gather through unity and contribute towards environmental preservation initiatives.” |

| Awareness (Derived from the study) | Most citizens struggle to obtain information related to the environment and prefer to receive such information. | “We had a recent experience with noise pollution. School students preparing for an examination were struggling, and they do not know to whom they should report.” “I mainly think about two things. 1. People do not know to whom they should bring issues 2. Sometimes although we raise concerns, they do not proceed to the next level.” |

| Human Welfare (Derived from the study, also found in [20]) | Citizens think about their welfare and the welfare of others. | “To live a better life and to provide our future generations a happy life, we need to preserve nature. However, with our busy work commitments, we are finding ways to contribute to environmental sustainability. This type of platform will allow us to communicate and contribute to environmental issues.” |

| Attitude (Derived from the study) | Citizens involve in pro-environmental behavior if they are aware of the impact of their actions. | “If you can somehow change people’s attitude towards environmental conservation, especially among young generations through these types of platforms, it will be a vital part of sustainability.” |

| Trust (Derived from the study, also found in [20]) | Citizens looking for active government engagement, providing better solutions, and winning the trust of the people | “This platform will become popular among people, and people will accept, and trust if this produces better results. The government endorsement and their high involvement in making things happen are crucial to this system.” |

| Value | Officers Comments |

|---|---|

| Authenticity | “Sometimes we receive complaints from the public merely due to personal grudges. Nevertheless, we expect them to act with utmost responsibility without wasting the time of officers for useless investigations”. “If the system is developed in a way to disclose personal identity, there are chances where some citizens will create fake profiles and communicate in the platform. Still, we are receiving so much anonymous information”. |

| Feedback | “We have an issue of scarcity of resources in providing timely solutions. For certain issues, we may need some time to depend on the type of issue”. “When people are given a chance to raise their voice, they may tend to make lots of queries, creating traffic. There should be a way in the proposed platform to filter the most relevant queries without spamming or creating unnecessary traffic”. |

| Accountability | “Citizens should understand that certain development projects are carried out in the country after an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) conducted by an expert panel. The citizen should understand that to achieve the development of a country sometimes certain changes may need to be done to the environment.” “Sometimes it is a challenge for us to listen to the policymakers or politicians elected by the people of the country and listen to the voice of the people while making sure to meet sustainability goals.” |

| System Feature Category (with Definition) | Example | Human Values Implicated in DGCP Design |

|---|---|---|

| Report—Citizens can report current environmental issues perceived as a threat or harm to the environment, and it may cause negative consequences to the environment or the future generation. Reported concerns are categorized and prioritized in the order of citizens’ interests. | “Honestly, there are enough and increasing environmental issues around us in the country threatening human life, biodiversity, and wildlife. We, as the public, are so eager to contribute and seek a formal way of reporting environmental issues and finding resolutions. At present, we lack a proper channel and are unable to reach out. The current practice of posting on social media has aggravated issues. Political parties and others make use of this information for personal agenda and create unrest among the people.” | Transparency, Safety, Universal usability, Feedback, Authenticity, Fairness, Representativeness, Accountability, Informed Consent, Trust |

| Propose—Citizens propose new and innovative ideas to preserve nature. Different people including general citizens, can presentideas to experts in solving current environmental issues or solutions as future directives to build a better sustainable nation. (Similar to an idea bank) | “Each and every citizen of the country is responsible for environmental protection. Without blaming administrative officers and the government, we can take responsibility as people living in this country for years. From the day we are born, we are aware of protecting our surroundings and can, therefore, suggest better ways. What we requireis the local or provincial environmental officers’ support in rolling out our plans.” “I am in my sixties, and I have vast experience in working with many projects towards Environmental Sustainability. However, I feel so distraught and feel like dying when nobody uses my knowledge and my experience to make our country better.” | Feedback, Representativeness, Human welfare |

| Share—Citizens share their day-to-day life experiences about environmental degradation and positive contributions to environmental protection (Environmental protection, knowledge dissemination and discussion). This provides the opportunity for people keen on environmental protection to have constructive dialogue. | “Why do we always promote environmental damage and negativity? Why notpromote positive vibes and create a trend that promotes pro-environmental behavior. Though it is difficult, if we change the people’s attitude towards environmental preservation, it can immensely assist in changing the mindset of people.” | Transparency, Safety, Authenticity, Representativeness, Awareness, Attitude |

| Discover—Citizens learn about environmental authorities’ policies, procedures, environmental indexes, etc. This serves as a knowledge base, and this is supposed to be controlled by the relevant authorities. | “We are so eager to gain knowledge on environmental policies, procedures, and best practices. As I believe, including me, much of our environmental knowledge is so poor. If we learn about the environment, it will empower us to be effective contributors towards environmental sustainability.” | Representativeness, Accountability, Legitimacy, Autonomy, Awareness, Trust |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sapraz, M.; Han, S. Implicating Human Values for designing a Digital Government Collaborative Platform for Environmental Issues: A Value Sensitive Design Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6240. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116240

Sapraz M, Han S. Implicating Human Values for designing a Digital Government Collaborative Platform for Environmental Issues: A Value Sensitive Design Approach. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6240. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116240

Chicago/Turabian StyleSapraz, Mohamed, and Shengnan Han. 2021. "Implicating Human Values for designing a Digital Government Collaborative Platform for Environmental Issues: A Value Sensitive Design Approach" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6240. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116240