Modeling Corporate Environmental Responsibility Perceptions and Job-Seeking Intentions: Examining the Underlying Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. CER Perceptions and Organizational Trust

2.2. CER Perceptions and Job-Seeking Attitudes

2.3. Organizational Trust, Job-Seeking Attitudes, and Job-Seeking Intentions

2.4. Organizational Trust and Job-Seeking Intentions

2.5. Sequential Mediating Mechanism of Organizational Trust and Job-Seeking Attitudes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. CER Perceptions

3.2.2. Job-Seeking Intentions

3.2.3. Job-Seeking Attitudes

3.2.4. Organizational Trust

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Overview of Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Test of Reliability, Validity, Multicollinearity, and CMB

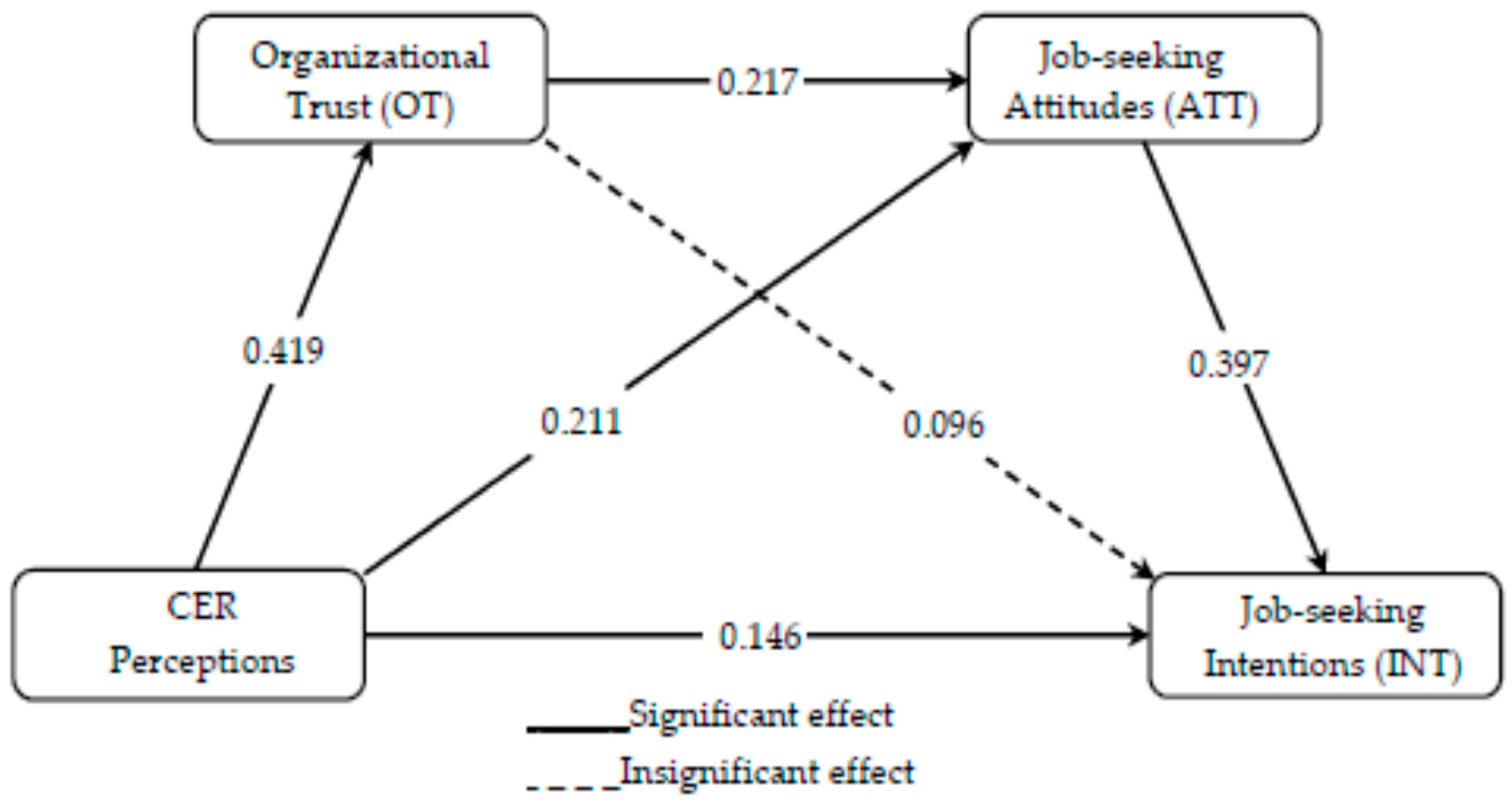

4.2. Test of Structural Model

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoang, L.V.; Vu, H.M.; Ngo, V.M. Corporate social responsibility and job pursuit intention of employees in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, B. Corporate social responsibility’s influence on organizational attractiveness: An investigation in the context of employer choice. J. Gen. Manag. 2018, 43, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loes, C.N.; Tobin, M.B. Organizational trust, psychological empowerment, and organizational commitment among licensed practical nurses. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2020, 44, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadarusman, K.; Bunyamin, B. The role of knowledge sharing, trust as mediation on servant leadership and job performance. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Lee, S.H. Perceptions of social performance in public enterprises and early job seekers’ intentions to apply. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Takeuchi, N.; Takeuchi, T. Understanding psychological processes of applicants’ job search. Evid.-Based HRM 2016, 4, 190–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson-Rasmussen, N.; Lauver, K.J. Do students view environmental sustainability as important in their job search? Differences and similarities across culture. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 16, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, A.E. Recruiting Employees: Individual and Organizational Perspectives; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 9780761909439. [Google Scholar]

- Dineen, B.R.; Soltis, S.M. Recruitment: A review of research and emerging directions. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, R. Green human resource management and job pursuit intention: Examining the underlying processes. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liao, G.; Albitar, K. Does corporate environmental responsibility engagement affect firm value? The mediating role of corporate innovation. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omisore, A.G.; Babarinde, G.M.; Bakare, D.P.; Asekun-Olarinmoye, E.O. Awareness and knowledge of the sustainable development goals in a University Community in Southwestern Nigeria. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2017, 27, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Hunt, A.; Jantan, A.H.; Hashim, H.; Chong, C.W. Exploring challenges and solutions in applying green human resource management practices for the sustainable workplace in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. Bus. Strateg. Dev. 2020, 3, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruepert, A.M.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L. The relationship between corporate environmental responsibility, employees’ biospheric values and pro-environmental behaviour at work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, R.; Balluchi, F.; Lazzini, A. Greenwashing and environmental communication: Effects on stakeholders’ perceptions. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson-Rasmussen, N.; Lauver, K.; Lester, S. Business student perceptions of environmental sustainability: Examining the job search implications. J. Manag. Issues 2014, 26, 174–193. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Penela, A.; Ruzo-Sanmartín, E.; Sousa, C.M.P. Influence of business commitment to sustainability, perceived value fit, and gender in job seekers’ pursuit intentions: A cross-country moderated mediation analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedharnath, U.; Shore, L.M.; Dulebohn, J.H. Organizational trust among job seekers: The role of information-seeking and reciprocation wariness. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2020, 28, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivato, S.; Misani, N.; Tencati, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: The case of organic food. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2007, 17, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmack, H.J.; Heiss, S.N. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict college students’ intent to use linkedIn for job searches and professional networking. Commun. Stud. 2018, 69, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, K.; Na, A.S.; Yee, W.C.; Xian, Y.C.; Jin, T.O.; Mun, S.T.; Shan, S.W. Influence of corporate social responsibility in job pursuit intention among prospective employees in Malaysia. Int. J. Law Manag. 2017, 59, 1159–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social identity theory. In Understanding Peace and Conflict Through Social Identity Theory; McKeown, S., Haji, R., Neil, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-29869-6. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, K.; Nikolaou, I.; Tomprou, M.; Rafailidou, M. The role of job seekers’ individual characteristics on job seeking behavior and psychological well-being. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2012, 20, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yizhong, X.; Lin, Z.; Baranchenko, Y.; Lau, C.K.; Yukhanaev, A.; Lu, H. Employability and job search behavior: A six-wave longitudinal study of Chinese university graduates. Empl. Relat. 2017, 39, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenders, M.V.E.; Buunk, A.P.; Henkens, K. Attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety as individual characteristics affecting job search behavior. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; ISBN 0201020890. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, D.D.T.; Paillé, P. Green recruitment and selection: An insight into green patterns. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 41, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Hur, W.M.; Kang, S. Employees’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility and job performance: A sequential mediation model. Sustainability 2016, 8, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781462534654. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, R. Can green human resource management attract young talent? An empirical analysis. Evid.-Based HRM 2018, 6, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 0138132631. [Google Scholar]

- Rafi, M.A.; Mamun, M.A.; Hsan, K.; Hossain, M.; Gozal, D. Psychological implications of unemployment among Bangladesh civil service job seekers: A pilot study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.T. Modeling corporate social performance and job pursuit intention: Mediating mechanisms of corporate reputation and job advancement prospects. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz, E.B.; Cáceres, R.C.; Pérez, R.C. Alliances between brands and social causes: The influence of company credibility on social responsibility image. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokur, A.; Caplan, R.D. Attitudes and social support: Determinants of job-seeking behavior and well-being among the unemployed. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 17, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.T. Application of planned behavior theory to account for college students’ occupational intentions in contingent employment. Career Dev. Q. 2011, 59, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanesh, G.S. CSR as organization-employee relationship management strategy: A case study of socially responsible information technology companies in India. Manag. Commun. Q. 2014, 28, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, R.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kantrowitz, T.M. Job search and employment: A personality–motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Cheng, J. Can a firm’s environmental innovation attract job seekers? Evidence from experiments. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, M.A.; Radnitz, C.L. Confirmatory factor analysis of the children’s eating behaviour questionnaire in a low-income sample. Eat. Behav. 2012, 13, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoye, G.; Saks, A.M.; Lievens, F.; Weijters, B. Development and test of an integrative model of job search behaviour. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, R.; Billsberry, J. The development and destruction of organizational trust during recruitment and selection. In Trust and Human Resource Management; Searle, R., Skinner, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Northampton, UK, 2011; pp. 67–86. ISBN 9781848444645. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Cappella, J.N. The role of theory in developing effective health communications. J. Commun. 2006, 56, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Organizational Behavior; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hooft, E.A.J.; De Jong, M. Predicting job seeking for temporary employment using the theory of planned behaviour: The moderating role of individualism and collectivism. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Gupta, R. Talent attraction through online recruitment websites: Application of web 2.0 technologies. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esch, P.; Black, J.S. Factors that influence new generation candidates to engage with and complete digital, AI-enabled recruiting. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Webb, T.L. The intention—Behavior gap. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaidi, Y.; van Hooft, E.A.J.; Arends, L.R. Recruiting highly educated graduates: A study on the relationship between recruitment information sources, the theory of planned behavior, and actual job pursuit. Hum. Perform. 2011, 24, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreurs, B.; Derous, E.; van Hooft, E.A.J.; Proost, K.; de Witte, K. Predicting applicants’ job pursuit behavior from their selection expectations: The mediating role of the theory of planned behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 761–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbel, J.D. Relationships among career exploration, job search intensity, and job search effectiveness in graduating college students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 59, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs and Items | CFA Loadings | CR | AVE | MSV | Cronbach’s (α) | Multicollinearity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||||||

| CER Perceptions | 0.852 | 0.542 | 0.244 | 0.843 | 0.791 | 1.264 | |

| CER5 | 0.800 | ||||||

| CER4 | 0.624 | ||||||

| CER3 | 0.836 | ||||||

| CER2 | 0.809 | ||||||

| CER1 | 0.571 | ||||||

| Organizational trust | 0.801 | 0.503 | 0.244 | 0.798 | 0.789 | 1.267 | |

| OT5 | 0.686 | ||||||

| OT4 | 0.750 | ||||||

| OT2 | 0.746 | ||||||

| OT1 | 0.670 | ||||||

| Job-seeking attitudes | 0.752 | 0.503 | 0.384 | 0.752 | 0.870 | 1.149 | |

| ATT4 | 0.688 | ||||||

| ATT3 | 0.726 | ||||||

| ATT1 | 0.714 | ||||||

| Job-seeking intentions | 0.782 | 0.644 | 0.384 | 0.773 | |||

| INT2 | 0.722 | ||||||

| INT1 | 0.875 | ||||||

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender a | 0.420 | 0.494 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Age b | 22.753 | 1.762 | −0.245 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Education c | 0.280 | 0.448 | −0.185 ** | 0.666 ** | 1 | ||||

| 4. ATT | 3.770 | 0.603 | −0.025 | −0.039 | 0.068 | (0.709) | |||

| 5. INT | 3.951 | 0.631 | −0.105 * | 0.147 ** | 0.120 * | 0.466 ** | (0.802) | ||

| 6. CER | 4.042 | 0.633 | −0.081 | 0.178 ** | 0.174 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.333 ** | (0.736) | |

| 7. OT | 3.833 | 0.601 | 0.006 | −0.024 | −0.002 | 0.306 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.419 ** | (0.709) |

| Model Fit Index | Measurement Model | Structural Model | Cutoff Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square (χ2) | 121.063 | 11.581 | |

| Degree of freedom (df) | 71 | 6 | |

| The ratio of χ2 to df (χ2/df) | 1.705 | 1.930 | ≤3 [48] |

| CFI | 0.973 | 0.988 | ≥0.90 [48] |

| SRMR | 0.040 | 0.037 | ≤0.08 [48] |

| RMSEA | 0.045 | 0.051 | ≤0.08 [48] |

| PCLOSE | 0.738 | 0.423 | ≥0.05 [48] |

| Fit Indices | Research Model | Alternative Models | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| χ2 | 11.581 | 80.207 | 26.268 | 19.576 | 27.16 | 15.237 | 73.782 | 29.925 | 44.151 |

| df | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| χ2/df | 1.93 | 11.458 | 3.753 | 2.797 | 3.88 | 2.177 | 10.54 | 3.741 | 4.906 |

| CFI | 0.988 | 0.845 | 0.959 | 0.973 | 0.957 | 0.983 | 0.859 | 0.954 | 0.926 |

| SRMR | 0.037 | 0.101 | 0.053 | 0.045 | 0.055 | 0.039 | 0.081 | 0.055 | 0.078 |

| RMSEA | 0.051 | 0.171 | 0.088 | 0.071 | 0.090 | 0.057 | 0.164 | 0.088 | 0.105 |

| PCLOSE | 0.423 | 0 | 0.036 | 0.151 | 0.029 | 0.327 | 0 | 0.028 | 0.002 |

| Notes: Model 1: CER → OT was fixed to 0 | Model 5: OT → INT was fixed to 0 | ||||||||

| Model 2: CER → ATT was fixed to 0 | Model 6: ATT → INT was fixed to 0 | ||||||||

| Model 3: CER → INT was fixed to 0 | Model 7: CER → ATT, and OT → INT were fixed to 0 | ||||||||

| Model 4: OT → ATT was fixed to 0 | Model 8: Full mediation (CER → ATT, OT → INT, and CER → INT were fixed to 0) | ||||||||

| Hypothesis No. | Path | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | SE | p | 95% CI (Low, High) | Hypothesis (Supported/Rejected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CER → OT | 0.419 | 0.046 | <0.001 | Supported | ||

| H2 | CER → ATT | 0.211 | 0.052 | <0.001 | Supported | ||

| H3 | OT → ATT | 0.217 | 0.054 | <0.001 | Supported | ||

| H4 | ATT → INT | 0.397 | 0.051 | <0.001 | Supported | ||

| H5 | OT → INT | 0.096 | 0.053 | >0.05 | Rejected | ||

| H6 | CER → OT → ATT → INT | 0.037 | 0.016 | (0.012, 0.073) | Supported | ||

| H7 | CER → INT | 0.146 | 0.052 | <0.01 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chowdhury, M.S.; Kang, D.-s. Modeling Corporate Environmental Responsibility Perceptions and Job-Seeking Intentions: Examining the Underlying Mechanism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116270

Chowdhury MS, Kang D-s. Modeling Corporate Environmental Responsibility Perceptions and Job-Seeking Intentions: Examining the Underlying Mechanism. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116270

Chicago/Turabian StyleChowdhury, Md Sohel, and Dae-seok Kang. 2021. "Modeling Corporate Environmental Responsibility Perceptions and Job-Seeking Intentions: Examining the Underlying Mechanism" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116270

APA StyleChowdhury, M. S., & Kang, D.-s. (2021). Modeling Corporate Environmental Responsibility Perceptions and Job-Seeking Intentions: Examining the Underlying Mechanism. Sustainability, 13(11), 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116270