1. Introduction

The call for papers for this Special Issue recognised the extent of destruction now occurring in the natural world as well as the dangerous situation our civilisation is now in. Recognising that environmentally-influenced societal disruption is already underway, the editors asked us “How can we disrupt the practices, structures, values, norms, manufacturing processes, relationships and/or foundational principles that form our thinking around organisations and guide our behaviour within them?” Their question was not about the established organisational domains of either positive ‘disruptive innovation’ or the ‘business continuity’ that is sought in the face of external stressors. It was in response to a perceived inevitability of disruptive change being forced upon organisations and societies and the implicit realisation that certain “foundational principles” in our organisations, societies, markets, and inner selves could be implicated as causal in those disruptive changes [

1]. Therefore, the editors asked us “How might rapid changes in social norms be achieved so as to prioritise pro-environmental values such as benevolence?” [

2]. This article responds to those questions by explaining and justifying an approach to the facilitation of group processes for facing societal disruption which explicitly invites participants to relate in ways that are different to what we, your authors, perceive to be problematic foundational principles for relating in modern societies (particularly in organisations). Our aim for sharing this new approach to facilitation is to offer a modality for people seeking to be helpful in a post-sustainability era, where past hopes now seem less valid or motivating [

3].

A normal response to the perspective that efforts at changing course have been failing, and that our organisations and societies will both experience and produce more degradation and disruption, has been to seek to quickly amass and articulate more knowledge about how to resolve the situation [

1]. Such a response rests on many assumptions, including the notion that learning and knowledge is about accumulation rather than shedding illusions, that speed of action is always good, that there is a foundational rightness in our society and worldviews, that more knowledge is what matters to situations [

4], that other people are less knowledgeable than we are, and that our difficult situation can be solved (see [

5] for a discussion of these habits within modernity). The research that we present in this article indicates that such assumptions are questionable and could limit the possibilities of responding creatively to societal disruption. Rather than rushing to acquire new knowledge about what to do in the face of fear-inducing failure and confusion, our research identifies the need for ‘unlearning’ dominant ways of relating with each other and ourselves [

6], which we will argue helped to create the disruptive situation in the first place.

Our hypothesis is that the way we gather in groups can provide opportunities for relating differently, which leads to a better quality of dialogue, so that more ideas for action will be surfaced. We surmised that this benefit could be experienced whether the focus of a process is on the inner aspects of facing disruption (such as the psycho-social, emotional, or spiritual implications) or the outer implications of that disruption (such as the organisational and policy implications, at family, community or country or international levels). Therefore, we believed that the facilitation of group processes would be key to this shift. Therefore, the professional practice of the facilitator became central to our focus. This is someone who supports individuals to learn collaboratively and experientially in a group, and whose legitimacy in this role is consented to voluntarily by members of the group [

7,

8].

This article presents a synthesis of the theoretical background we used to inform our practice as facilitators of gatherings related to societal disruption since 2018 when the concept of “Deep Adaptation” to societal collapse began to rise to prominence [

9]. It provides our initial conclusions on how to facilitate such gatherings, which arise from a few years of ‘first-person inquiry’ as reflective practitioners of facilitation. We outline some important aspects for the facilitation of any dialogue relating to the anticipation of disruption or collapse, touching on matters of containment, radical uncertainty and allowing difficult emotions. We identify the process of ‘othering’ both people and aspects of ourselves as a key barrier to meaningful dialogue, and so recommend an approach we term ‘Deep Relating’ as a helpful component of any facilitated dialogue on disruptive change.

2. Materials and Methods

When a person is actively engaged in a practice or community, there is a closeness to the social reality which is not possible from research by a person external to the situation. In many situations, where phenomena appear to be new and emergent, it is useful to learn quickly about the general qualities of a situation and share these with others. Therefore, there is a key role for knowledge to be conveyed through reflective practice by engaged professionals, rather than waiting for experiments or formal efforts at data collection by third parties to test predetermined hypotheses [

10]. The ideas shared in this article are the result of two reflective practitioners who facilitate processes focused on aspects of the anticipation of societal disruption and collapse. This is particularly appropriate for the topic, as although facilitation is an established field, applying it to the topic we do is still a highly unusual yet fast-developing phenomenon.

Our approach is therefore a form of action research, where we participated in the practices we were analysing, with the aim of improving our practice. Moreover, it was limited to ‘first-person inquiry’, where we analysed and recording our own practices and initial sense making [

11]. Together, we have participated in well over 50 gatherings (in person and online) that relate to societal disruption or collapse, that were facilitated by people using some of the approaches we outline in this article. In addition, the combined number of gatherings (in person and online) that we have facilitated on these topics is over 20, including one-day conferences, 2-h webinars, intensive week-long courses (online and in person) and retreats. Participants included all ages of adults, from all continents, with a range of professional interests from business, government, academia and civil society. All events were in English and approximately half of the participants were from the UK. In addition, we have participated in many dozens of gatherings that use modalities with some similarities to the ‘Deep Relating’ modality we outline in this article, though without a context of anticipating disruption or collapse [

12].

Our inquiry was not limited to the studying of specific facilitated events, as it was complemented by our ongoing attention to how both we and other people relate in general to the matter of collapse anticipation. That ongoing attention was framed by an intention to learn how we could find some calm and agency in our lives without denying how bad the situation has become—and to help other people to do the same. That approach reflects the invitation from the ‘Living Theory’ strand of action research which invites researchers to consider any tensions between their values and practices [

13].

During the two years of reflective practice of facilitation for Deep Adaptation, we each had periods of autoethnographic data collection. Autoethnography is a form of qualitative research in which an author uses self-reflection on personal experiences to describe and critique cultural norms, beliefs, and practices [

14]. Typically, it involves an intention to be aware of those cultural processes as one engages with others, and to take notes about one’s feelings, thoughts, questions and insights soon after specific experiences [

15]. A presentation of some of that autoethnographic data is available elsewhere [

12], as in this article we seek to provide a comprehensive theoretical background for our practices and offer a synthesis of the findings.

All these schools of thought on social research respond to the insight that to inquire into social realities, we must immerse ourselves in the complexity, uncertainty and emotion of life, rather than seek to separate ourselves from it with stories of objectivity or the possibility of defining simple causal relations. As may become apparent from the theoretical framework that we will develop in this article, we disagreed with the requirements of this journal to include a section titled “materials and methods” as well as a linear structure of progression of argumentation, where experiences and insights are restricted to the concept of experimental “results”. For us, such ideas are a relic from the triumph of scientific empiricist discourse over all other ways of being and knowing, which took root in Europe during the Age of Enlightenment. Despite decades of critique of the importing of such approaches into social inquiry, the discourse remains dominant in the way many academic journals conceive of quality research. That dominant approach both reflects and enacts patriarchal oppression of wider forms of knowing [

16]. In this article, we will describe how this ideology is at the root of the unsustainability of contemporary society, making this journal’s approach both ironic and illustrative of the incapacity of mainstream academia to have broken free of ideological systems of exploitation and oppression. Fortunately, such an approach has begun to lose its power in orienting people in their world due to the obvious complexity and ambiguity of life, and the dominant culture’s inability to have significantly perceived its vulnerability [

17]. Therefore, as researchers we refuse to relegate our work to the category of opinion, or review, and instead assert that this work offers knowledge.

Our “materials” for this research were our bodies. Not just our heads. We have sat in gatherings where we have cried, or been angry, and held others in their fear and grief, while seeking to notice our bodies reacting in various ways to various thoughts and interactions with people. Therefore, much of the learning on this topic has been experiential, and thus impossible to convey in this form of academic writing. However, our aim is to offer a basis for understanding which could support further inquiry on how to host meaningful dialogue towards effective action in a context of disruptive change in society.

3. A Greater Introduction to Theoretical Contexts for Group Facilitation in the Face of Disruption

Although the traditional linear approach to presenting research findings involves a summary of a literature review before then identifying questions that are explored with the generation and analysis of data, that is both insufficient for an exploration of a topic as wide as the one in this paper, and inconsistent with our chosen methodology as engaged practitioners. Reflective practice and professional learning both involve an ongoing interrelating of insights from experience, relevant scholarship, and dialogue with others about emerging issues and ideas. It was that process over a few years which led us to identify key theoretical contexts for group facilitation in the face of societal disruption. Before presenting our findings on the specific matter of facilitation, we therefore wish to offer a significant amount of theoretical context, drawing from transdisciplinary and iterative exploration of literature. First, we explain the context of collapse anticipation and the emerging field of ‘Deep Adaptation.’ Second, we explore some deeper critiques of how humanity has created this situation of precarity. We summarise some forms of ‘othering’ aspects of self, other and nature, as well as some of the mental habits that are prevalent within modernity, which we hypothesised can be usefully loosened through facilitated processes.

3.1. The Context of Collapse Anticipation and Deep Adaptation

Increasingly, people amongst the general public and within professional fields go further than warning about the worsening situation with the global environment and now predict societal breakdown or even collapse [

1,

3,

9]. ‘Deep Adaptation’ is a term for describing an agenda and framework for responding to the potential, probable or inevitable collapse of industrial consumer societies, due to the direct and indirect impacts of human-caused climate change and environmental degradation [

18]. The term became popular after the release of an Occasional Paper from the University of Cumbria in 2018, which caught the attention of readers far beyond its intended audience of sustainability professionals, being downloaded over a million times. In response, your authors helped to develop the Deep Adaptation Forum (DAF) in order to provide a means for people to connect with each other for dialogue, support and initiative based upon their anticipation of societal collapse. With the term ‘societal collapse’, we mean an uneven ending of industrial consumer modes of sustenance, shelter, health, security, pleasure, identity, and meaning. Rather than an environmental, economic, or political collapse, the word ‘societal’ is important as these uneven endings pervade society and challenge our place within it. The term collapse does not necessarily mean that suddenness is likely but describes a form of breakdown in systems that is comprehensive and cannot be rebounded from to return to what was before. The word ‘deep’ is intended to contrast the agenda with mainstream approaches to adaptation to climate impacts [

19], by going deeper into the causes and potential responses, both within ourselves, our organisations, and societies.

The people engaging in Deep Adaptation (DA) believe that societal collapse in most or all countries of the world is either likely, inevitable, or already unfolding, and aim to respond by reducing harm. Typically, such people believe that they will experience this disruption themselves, or that they have already begun to do so, while recognising that the disruptions are being experienced first and worst by people in the Global South. Therefore, Deep Adaptation describes the inner and outer, personal and collective, responses to either the anticipation or experience of societal collapse, worsened by the direct or indirect impacts of climate change [

9]. Framing Deep Adaptation (DA) as a series of questions in the original paper made it a call for conversation, rather than advocating any answers [

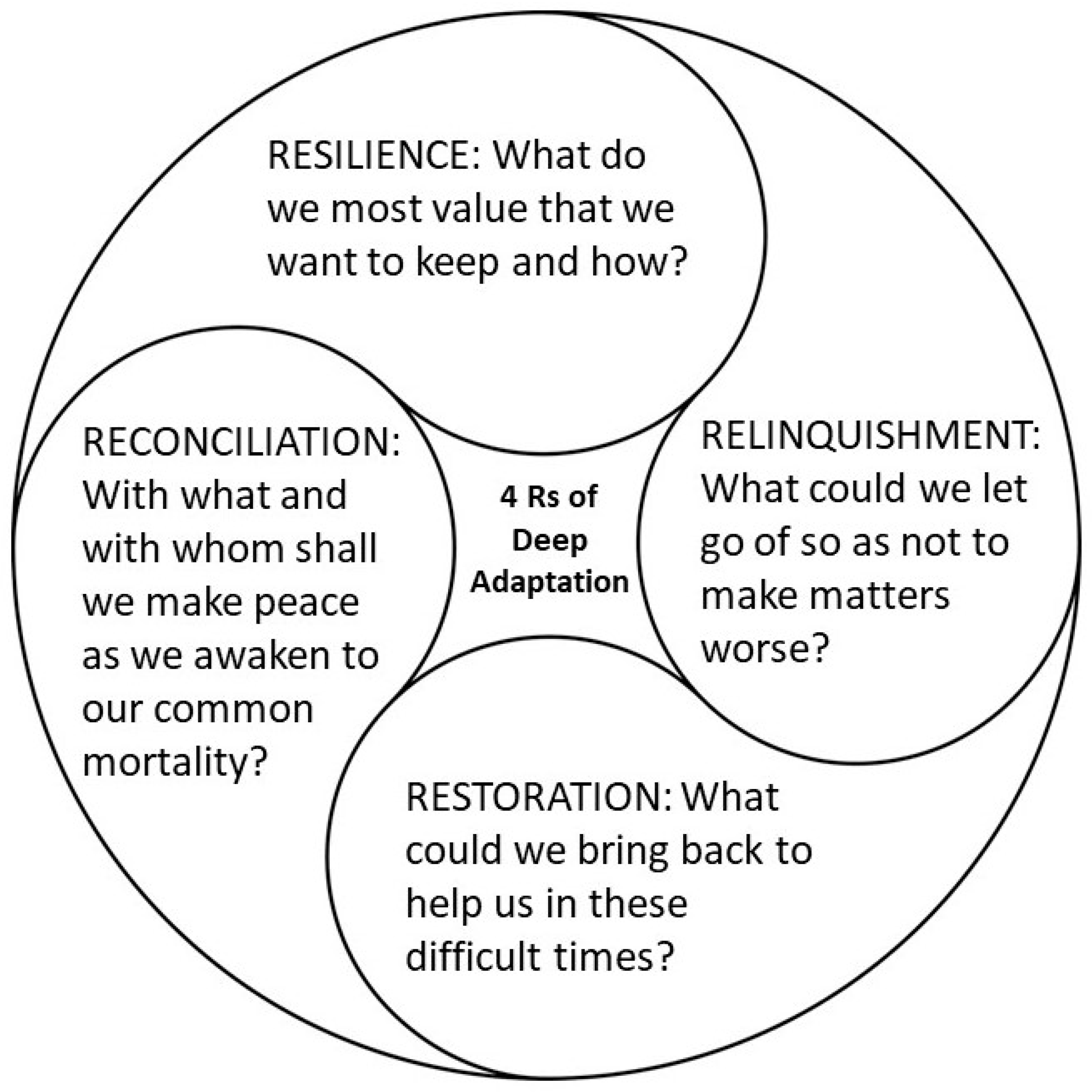

18]. “What do we most value that we want to keep and how,” is a question of resilience. “What could we let go of so as not to make matters worse,” is a question of relinquishment. “What could we bring back to help us in these difficult times,” is a question of restoration. “With what and with whom shall we make peace as we awaken to our common mortality,” is a question of reconciliation [

9]. These ‘four Rs’ have provided a framework for thousands of conversations around the world (see

Figure 1). However, they are not in themselves a modality for how to host and facilitate useful dialogue on the implications of our environmental predicament.

Facilitating dialogue about these issues over the last few years we have discovered the benefit of helping participants to experience ways of relating that can bring awareness to unconscious patterns. Group processes can be an opportunity for us to experience a different way of relating to difficult information, difficult emotions, and to each other. We can help each other learn how to be with our difficult emotions, without suppressing them and consequently reacting by unconsciously grasping for habituated ideas or stories that might offer relief or distraction. Our intention in enabling such conversations has been that more of us might avoid adopting simplistic narratives of blame or salvation, and the unhelpful action that might then arise. More of us might discover alternative ways of responding to our feelings of anxiety than voting for a proto-fascist government or building walls around our vegetable gardens or countries. To help with that process, facilitation needs to be effective in providing a container for radical uncertainty, a ‘liminal space’ in which people can build stamina for being with insoluble dilemmas and the challenging emotions surrounding them, through developing skills of emotional self- and co-regulation. It needs to invite ongoing courageous self-inquiry and a willingness to let go, within a wider container of compassion, acceptance, forgiveness, humility, and accepting mistakes (our own and others’).

3.2. Exploring Possible Causes of Our Predicament

To seek to reduce harm in the face of societal disruption and collapse must involve an exploration of the socio-cultural mechanisms that have led to humanity’s failure to live harmoniously with the wider system of life on earth. If we do not explore those mechanisms of disruption, then we risk making matters worse by our responses. Such socio-cultural mechanisms are not outside of us but are socially reproduced through our own feelings, thoughts and behaviours. Therefore, all of us who have lived the kind of modern lives that mean we read an article such as this one are both products and producers of a culture that has led us into a situation of biological annihilation. The implication is that the way we show up and relate within groups and organisations is important to reconsider. Because these are moments when the socio-cultural mechanisms of destruction are reproduced, discursively.

Before outlining the principles for facilitation of conversations about aspects of societal disruption and collapse, we will summarise some of our insights on the socio-cultural mechanisms of destruction, which then inform the mode of facilitation that is being used by many DA groups. While there is insufficient space in this article to offer a comprehensive explanation of a theory of culture, in this section we will focus on two synthesising frameworks. First, the concept of ‘Othering’ and its centrality in the process by which people can destroy nature and oppress each other. Second, the concept of the ideology of ‘e-s-c-a-p-e’ and the way that it institutionalises Othering in all aspects of our lives through six mental habits [

20].

3.2.1. ‘Othering’ and Its Remedies from Facilitation

We have found the philosophical concept and psychological phenomenon of the ‘Other’ to be useful in shaping our practice of facilitation. It was first introduced by Hegel in the 18th century in order to describe the necessary counter-image to the ‘self’. He explained that in order to hold a sense of self, we must construct a constitutive individual or collective ‘Other’ which we define as different from, and ‘less than’ or ‘inferior to’ oneself or to the group to which one identifies as belonging [

21]. Othering is a psycho-social process which is implicated in discrimination of all kinds (race, gender, class, age, etc.). It is closely connected to Marx’s concept of ‘alienation’ (the ‘worker’ is alienated from aspects of their humanity through being reduced to an economic entity in service of capitalism [

22] and has been influential in the evolution of feminist theory, sub-altern and critical race studies [

5]. The process of othering makes it easier to dehumanise people or groups and conclude that they are unworthy of respect or dignity, and scholars are increasingly incorporating an analysis of othering in theorising about genocide and nationalist ideologies [

23]. Othering can also be seen at the root of the imagined separation between humans and non-human life, and the desacralisation of nature. A ‘Deep Ecology’ perspective invites a non-anthropocentric account of the relationship between ‘humans’ and nature [

24]. The cultural assumption of humanity’s assumed superiority above all other non-human life—and therefore our entitlement to manage and consume—is central to the Western worldview, and is often traced to the Judeo-Christian tradition, and translations of the Bible that give ‘man’ dominion over the earth [

25,

26].

If each of us valued all other life, human and non-human, as much as we value ourselves, or that with which we identify, could we participate in systems of oppression and destruction? We do not know, because we are all immersed in our internal processes of othering. Othering occurs because our self-construal is predicated on identifying that which is not ourselves—whether that is other views, other behaviours, other people, and even other life at large. Othering is, fundamentally, a process of objectification; by naming and defining something, someone, or group of someones, we are subtly separating ourselves—as the agentic subject—from the other, as the passive object upon which we act. The modern worldview considers a person as the subject who observes everything else that ‘he’ encounters, which involves the objectification of whatever is encountered. We use the masculine pronoun purposefully here, referring to the feminist critique of rational objectivity as being inherently patriarchal [

27]. Objectification of myriad ‘others’ then expresses itself in various habits of thought that appear in modern communications, particularly in the fields of management and bureaucracy [

28]. Because this worldview is embedded in the very building blocks of the way we communicate—our language of subjects acting upon objects—we can call this a ‘grammar of being’ which both reflects and enables othering.

As we became aware of how othering could lie at the root of both oppression and destruction, we wondered what might be useful in our work as educators and facilitators. We learned that othering is constituted relationally when people interact [

29] and so an approach which enables people to ‘notice’ this widespread phenomenon as it arises within them and find ways of making choices that are less driven from that impulse, will be essential to the cause of reducing the potential for future harm. We found that insights from critical theory and Buddhism, and the connections between the two [

30] to be particularly helpful, alongside experiences of sitting in circles with the intention of unusually transparent and vulnerable sharing of thoughts and emotions.

Critical theory is useful in bringing attention to how processes of othering are expressed through language and culture in ways that crystallize unequal power relations. Critical theory is a movement in social and political philosophy which seeks not only to understand those processes, but to dismantle them in order to reduce inequality and oppression [

31]. Such theory invites us to become more aware of the language, symbols and behaviours that we use and that surround us, and how they are all involved in reproducing power relations. For instance, a newspaper headline, an advert, a form of speech, or manner of dressing, can all be stimuli that convey meanings with normative or power-laden dimensions [

32]. By becoming more aware of such processes, we develop what is described as critical consciousness or criticality [

33]. That is a way of interpreting the world and oneself, where attention is given to possible normative or power-laden dimensions of any meanings intended or received from any stimuli so one can choose to either disengage or disrupt [

34] (p. 113). Although there are modalities suited to classrooms, such as the ‘critical reading’ of texts, our climate predicament invites modalities for the development and everyday application of critical consciousness, particularly in group settings. We therefore concluded that it would be useful that facilitation for DA includes efforts to invite critical reflection on any cultural norms, often as expressed in language.

An additional source for insight on how facilitated processes could bring attention to, and hopefully overcome, processes of othering, has been Buddhist philosophy and practice. One of the basic tenets of Buddhist teachings is the realisation of impermanence. The perspective that the self is an unchanging, separate, and coherent phenomenon is not recognised in Buddhism. Instead, we are invited to consider, and through insight meditation to experience, the self as a moving assembly of sensations, emotions and thoughts [

35]. The potential of experiencing self in that way is that we become less attached to the processes of self-construal, as we described above, and therefore less engaged in unconscious othering. Through meditation practice, we are also invited to notice how we are either averse to or desirous of certain thoughts and emotions, in ways that can influence our decisions about what to focus on or what to believe to be true. That level of detailed attention to our inner thoughts and emotions can help reveal the moments when we label and judge stimuli of any kind, and whether we accept an idea or not. If people can bring that greater awareness into the moment of interpersonal interactions in order to maintain an orientation towards inter-subjectivity in their relations with others [

36] and a more ‘critical’ interpretation of everyday culture, then there is greater opportunity for disengaging or disrupting systems of oppression and destruction.

Our experience is that the approach to facilitation outlined in this article is helpful for promoting ‘critical consciousness’ in general. By that, we mean an understanding of the way that each of our assumptions and thoughts are shaped by culture, in ways that reflect and reproduce power relations. Assumptions can be as deep as those around certainty, progress, grief, or ‘unwelcome’ emotions. Typically, critical social theory has been taught in ways that invite us to analyse texts for their ideological content and effects on readers (and the people or lifeforms being described in those texts). Such a deconstruction of texts can be revelatory, especially if it invites a focus on our inner emotions and how that influences how we adopt or reject certain framings of reality. With DA facilitation, there is an invitation to go deeper in exploring how our own identities can be usefully regarded as a text, both reflecting and reproducing ideologies. Therefore, we have found processes like Deep Relating (described below) to be useful in deepening participants’ ability to notice our inner processes of the social construction of power and ideology. This provides opportunities for a transformation of people’s self-construal and ways of being in the world. Therefore, we recommend educators consider using some of the processes of facilitation described in this article, particularly when intending to support critical consciousness.

3.2.2. The Mental Habits Arising from Othering: The Ideology of E-S-C-A-P-E

In our work with groups on the implications of collapse anticipation, we have come to recognise that processes of mutual liberation from imagined separation and othering can come with risks, given the individualism that most of us have been socialised into. We have perceived how the process of self-construal that requires othering is accentuated if we assume or wish for a fixed and unchanging self, rather than a fluid and uncertain phenomenon. It is also accentuated if we assume or wish for that self to be the autonomous author of our lives, rather than the expression of complex relations. More so, if we assume or wish for our self to be good and better than others. Therefore, any attachment in us to the idea of a self that is whole, sovereign and good, can make ‘othering’ more compulsive. Paradoxically, this means that the belief that one can become a self-actualized good human being could become a contributor to further oppression and violence. Therefore, if we wish to become less unconsciously oppressed by imagined separation, and less involved in reproducing othering in society, it is useful to become more aware of our inner processes of othering. That led us to identify mental habits arising from and reinforcing othering.

The ideology of ‘e-s-c-a-p-e’ is a concept developed by one of your authors to summarise some of the inner processes within individuals which are produced by—and reproduce—contemporary culture in most urban societies [

20]. It comprises our assumptions of, or beliefs in, the following: entitlement, surety (which is another word for certainty), control, autonomy, progress, and exceptionalism. Entitlement refers to a widespread assumption that we are entitled not to feel emotional pain and suffering; that we are entitled to have our inner worlds heard and validated; and that we are entitled to have more than our basic needs met. This is despite the huge suffering caused in order to produce the lifestyles that many of us enjoy. Surety refers to the threefold assumption that we can be certain of reality, that it is good to be certain, and that there is a universal standard through which we can all agree what is reality and how to know it. Control refers to the idea dominant in modern culture around the world, not just the West, that it is possible for the human, both individually and collectively, to control the environment and others, and that it is good to do so. This is despite the growing realisation of how we have dangerously destabilised the climate in a way that might even pose a growing risk to our own species [

37]. Autonomy refers to the idea that each of us is the separate autonomous origin of our awareness, values and decisions, and that it is good to become more autonomous. Progress refers to the widespread assumption—and often devout belief—that humanity is advancing from the cave to the stars, through a process of civilization without interruption. This is despite evidence of growing social malaise [

38] and our driving of mass extinction of life on Earth [

39]. Exceptionalism refers to the twofold assumption that we and our kin are different and better, or at least more entitled than others and their kin; and secondly, that humans are an exceptional species in natural history [

20]. This is one of the deepest mental habits of e-s-c-a-p-e, which has been described elsewhere as alienation; the imagined separation of ourselves (or large parts of ourselves), from each other and the wider web of life [

26].

This ideology of e-s-c-a-p-e is produced through us in all our social interactions, and therefore shows up in, or frames deliberations about what to do in the face of societal disruption and collapse. For instance, the habit of entitlement involves thinking, ‘I expect more of what I like and to be helped to feel fine.’ Surety can involve thinking, ‘I will define you and everything in my experience, so I feel calmer.’ The mental habit of control can involve thinking, ‘I will try to impose on you and everything, including myself, so I feel safer.’ Autonomy can involve assuming, ‘I must be completely separate in my mind and being because otherwise I would not exist.’ Progress can involve thinking and feeling, ‘the future must contain a legacy from me, or make sense to me now, because if not, when I die, I would die even more.’ Exceptionalism can involve thinking that, ‘I am annoyed in this world because much about it upsets me and so I believe I’m better and/or needed’ [

20]. If unacknowledged, these mental habits will restrict the potential for dialogue about the incredibly difficult and necessarily highly emotional conversations about the precarity of our societies in the face of rapid environmental change. They may restrict the potential for insights on how to reduce harm, or even lead to counterproductive agendas and plans.

The rise of the ideology of e-s-c-a-p-e in the modern era is predicated upon, and further galvanizes, our inner processes of ‘othering’. For the mental habit of entitlement, we must consider ourselves differentially worthy of good experiences. For the mental habit of surety (another word for certainty), we must consider the rest of life to exist meaningfully only in ways that we choose as mattering to us. For the mental habit of seeking to control, we must objectify and reduce the subjectivity of that with which we seek to control. For the mental habit of assuming our autonomy, we must reduce the significance of all which influences and creates who we are. For the mental habit of assuming progress, we must consider the world primarily as material to be shaped. For the mental habit of exceptionalism, we must consider ourselves to be better than other people.

4. Results from First-Person Inquiries: Principles and Practices for Facilitating Conversations on Societal Disruption and Collapse

The results of our first-person inquiries as facilitators of Deep Adaptation gatherings, both together and apart, confirmed to us the validity of our hypothesis that facilitating groups can provide opportunities for relating differently—emotionally and vulnerably—to the norms in organisational life, in ways that lead to an unusual quality of dialogue, so that more ideas about oneself and the possible for action are surfaced. It is early days for the topic of Deep Adaptation to climate chaos, and early days for this form of facilitation on this topic. Therefore, we did not try to analyse any impacts on learning outcomes, outputs and ultimate impacts in communities, organisations and societies. Follow on research could explore and analyse participant perceptions on these matters, as well as compare outcomes from processes that use the facilitation methodology, we outline in this paper with outcomes from more traditional approaches to running meetings. What our exploratory first-person inquiry was able to identify were four key themes for effective facilitation of gatherings that engage matters of collapse anticipation. These are co-creating safe enough containment, accepting radical uncertainty, allowing difficult emotions and making time for ‘Deep Relating’. In the following section, we will explain each theme, which also involves explaining the modality of ‘Deep Relating’.

Each theme resonates significantly with the approach to facilitation advocated some years ago by Wilfred Bion [

40]. He identified how there are widely shared assumptions that groups gather together to avoid conflict and confusion, and to conclude with positive resolution to discussions. He also identified how participants typically make basic assumptions about what a group is thinking, feeling and aiming for, which then determine interactions in limiting ways. Therefore, he proposed that facilitators seek to bring assumptions to the surface and challenge them, which can make group processes seem more challenging rather than pleasant [

40].

4.1. Co-Creating Safe Enough Containment

A fundamental element of the process of group facilitation is to provide containment, described by Ringer [

41] as “group members having the conscious and unconscious sense of being firmly held in the group and its task”. Containment, in the context of DA, is creating a space, and conditions, in which people feel

safe enough to feel and express their most difficult emotions relating to societal disruption and collapse, or to reveal the ways in which the discursive foundations of the micro-violences of othering are internalised and unconsciously enacted in our interactions with each other. Containment is a fundamental aspect of facilitation practice, and paramount in facilitation for Deep Adaptation.

Smit [

42] has proposed two aspects of containment—external (“hard”) containment (or the structures that form the context in which the facilitation is taking place), and internal (“soft”) containment (or the qualities of presence that the facilitator brings to their role). External containment begins well before the gathering takes place and includes the clarity of the ‘call’ or invitation (will people experience what they are expecting to experience?), administrative arrangements for participation, and joining instructions. It also includes (in face-to-face gatherings) giving intention to the space, accessibility, comfort, as well as ensuring that physical needs of the participants, and facilitators, are met. Internal containment includes such qualities of the facilitator as a non-judgmental presence, trustworthiness, support, empathy, and consistency, and practices that enable these.

Recognising the insights of Deep Ecology [

24], we suggest including a non-anthropocentric, non-Western empiricist paradigm in the creating of a sense of containment. For some, this may mean inviting and giving thanks to ancestors (human and non-human) or invoking the feeling of being held by and in service to the earth. For others, it means connecting with a higher power (implicitly or explicitly), connecting with our own teachers, and honouring the presence of collective wisdom rather than individual approaches.

Although containment has typically been understood as how the facilitator creates a ‘safe space’ for participants, this is problematic for a number of reasons. First, the context of facilitation on societal disruption and collapse is not only inherently unsafe (considering the implications of the loss of security, sustenance, and meaning), while much of humanity’s harmful action throughout history has arisen from a felt or perceived need for safety and security. Second, a sense of safety is a subjective experience; for example, what feels like a safe space for a male participant who is white may be experienced as very unsafe by a woman of colour, or anyone else who is a member of a group which has been systematically marginalised by dominant culture. Thirdly, the facilitator is not unaffected by what is being explored, so it is appropriate to positively acknowledge that emotional involvement to themselves and the participants. For these reasons, we recommend that spaces are always co-hosted by two or more people, and that careful and honest attention is given to the relationship between and amongst co-facilitators. In any group situation, our own boundaries as facilitators can begin to collapse; each of us has our own unconscious patterns and beliefs, which, when triggered, mean we may begin to lose a sense of integrity, and consequently our ability to ‘hold space’ energetically can be compromised. The concept of accompaniment in psychotherapy offers a useful metaphor: the collapse of stories of self, of previous architecture of meaning, requires the possibility of letting go into a liminal space.

Given that the context of Deep Adaptation to societal collapse is a topic that is experienced as inherently unsafe, and that safety is relative and subjectively experienced, the aim of giving attention to containment and boundaries challenges the myth that it is possible to create a safe space. Instead, we give attention to holding a space that is

safe enough, and inherent in that process is increasing our capabilities for emotional self- and co-regulation. Facilitating for Deep Adaptation is about becoming more resilient, by building our stamina for tolerating difficult emotions, and the sobriety to be able to take considered generative action, rather than turn towards what feels more pleasurable, easy, or comfortable. Creating a safe enough space does not make what happens inside the container more comfortable; it makes it more possible for us to hold ourselves and each other in discomfort [

43]. In that sense, our insight resonates significantly with the tradition of facilitation known as the Tavistock Method [

40].

4.2. Accepting Radical Uncertainty

These are unprecedented times, challenging people’s sense of self, security and agency, with the fear of societal collapse and even human extinction, triggering fear responses [

44,

45]. As people from all walks of life, including climatologists and policy makers, feel anxiety, that can encourage habitual responses which will be unhelpful for wise action. Of particular concern here is an over-emphasis on ever more detailed measurement, along with an aversion to diverse ways of knowing, holistic analysis, and consequent inhibited ability for wise discernment within ambiguity. If we take the exponential increase in human-caused carbon emissions as our indicator, many decades of climate science have not had an impact in reducing the unsustainability of society [

18]. We have become better at measuring and at producing more measurements. Stepping back from the specific researchers and their research, our society’s emphasis on measurements can be regarded as a manifestation of contemporary discomfort with living in a state of uncertainty—the emphasis on ‘surety’ within the ideology of e-s-c-a-p-e. Within the culture of modernity, “man imagines himself free from fear when there is no longer anything unknown” [

46] (p. 16). Therefore, when perceiving either physical or intellectual vulnerability, the response of the ‘overmodern’ mind is to reach for further data and analysis, rather than allow difficult emotions while exploring the implications of existing information. Such a response is typical within the currently dominant culture of ‘overmodernity’, which has extended any benefits of modernity to a degree that has made humanity overshoot natural limits.

An emphasis on a positivist-scientific response to perceived threats is unhelpful when it maligns more diverse forms of insight as well as the state of not-knowing. In the worst manifestations of this ideology, people can condemn more holistic analyses and suppress anything uncertain and threatening. In addition, rather than remain in a state of uncertainty, people may unconsciously choose to adopt simplistic stories of blame and safety, such as political narratives characterised by racism, nationalism and authoritarianism. With its emphasis on the social construction of our ways of knowing the world, critical theory teaches us that certainty is an illusion [

47]. That view echoes many spiritual traditions. Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and indigenous worldviews suggest that human agency is not central; rather, humans are understood as being

in relation with other forces within a reality we cannot fully comprehend. These sources of wisdom recognise the possibilities for a felt sense of interbeing, humble appreciation of our interdependence, and openness to integrate insights from multiple ways of knowing our world [

48].

Reducing culturally—produced resistance in all of us to letting go of our previously assumed certainties about the world, knowledge and personal identity is therefore important for facilitating any conversations about the new era of societal disruption and collapse. Enabling people to feel more equanimity with uncertainty and ambiguity, within a context of people perceiving increasing vulnerability and change, is therefore a key aim of holding space for Deep Adaptation.

4.3. Allowing Difficult Emotions

The affective dimension of experience has been repressed by the overmodern worldview, or relegated to a domestic and feminine sphere, outside of mainstream discourse. The dominant discourse suppresses emotionality of any kind, which means that both aversion to difficult emotions and their suppression are likely to be influencing the way people engage in any dialogue on societal disruption and collapse. Therefore, effective facilitation on such topics can make explicit that whereas there are assumptions that avoiding emotions and staying positive is expected in professional life (and society generally), emotional aversion and suppression is not welcomed in the dialogue. Rather, checking in with one’s own emotions and being present and non-judgemental towards both those emotions and the emotions of others is regarded as an important aspect of meaningful dialogue.

In particular, any emotions related to our sense of loss and vulnerability need to be welcomed in dialogues on societal disruption and collapse. As the implications of that predicament are becoming more widely acknowledged, the field of psychology has been exploring the phenomenon of ‘eco grief’ [

49]. Within that field of expertise, the general agreement is that Western culture is grief-phobic, meaning that unpleasant emotions associated with grieving are problematized and framed as needing to be relieved and overcome. It is typical in overmodern cultures for people to dismiss any discussion of loss, death and grief as ‘macabre’ and an indication of someone having a problem or being embarrassing. A critical-theoretical perspective on this phenomenon suggests that “the social rules that govern the expression of grief, the role of attachment, social pain, and shame [are] potent forces that promote compliance with social rules” [

50] (p. 241). Suppression of different aspects of grief can result in becoming stuck in denial [

51]. Collective acceptance of our predicament, by becoming enabled to move through all of the difficult emotional experiences, is one way of finding loving equanimity in collapse [

49].

To write about the emotion of grief by discussing expert analysis risks repeating the deadening patterns we have criticised so far in this article. So we will take a moment to share with you in a different way. We know that grief decimates and destroys us. In the depth of the grieving process, we lose connection with our sense of self, and everything that previously seemed certain about the world, the familiar landmarks of our person, our relationships, and our social context. It feels unbearable. Additionally, in fact, the self that encounters it cannot bear it, because that self is not big enough to comprehend it. The boundaries of our self are broken down and expanded in order to become big enough (or have an increased capacity for) integrating the experience of loss. A new self emerges, one that is created during the journey of integrating the incomprehensible—and that which seemed unbearable.

The predicament of societal disruption and collapse is one that involves suffering, loss and death of many kinds: thousands of species going extinct, whole ecosystems being destroyed, millions of people starving and being displaced, and the threatened future of our younger relatives [

1]. Furthermore, there is the additional sense of loss as the society and culture we had assumed would continue and that we could contribute to now appears finite. Therefore, allowing for the emotions arising in response to full recognition of this multi-dimensional dying is important in any dialogues on what to do about the predicament.

4.4. Making Time for Deep Relating

As facilitators of gatherings on societal disruption and collapse, we have found that it is helpful to make time for a special phase of interaction, which invites people into different ways of relating, where emotions are not suppressed. The aim is to practice a way of relating which explicitly seeks to avoid the overmodern patterns of othering and e-s-c-a-p-e that we described above. We use the term “Deep Relating” to describe this modality, which we will now summarise.

Deep Relating is a relational meditation practice, or an approach to being in relationship with another person, or group of people, in a way that is grounded in a deep and detailed awareness of present moment experience. Participants are invited to speak from—and of only—what is arising in the ‘here and now’, which can include physical sensations (including what is seen and heard), emotions, and thoughts. Then, trying to articulate what is experienced as clearly as possible with the intention of inviting the other into your world for deeper connection. People are invited to notice when the impulse to ‘tell stories’ arises, that is, to explain, justify, or evaluate experience by referencing past or future, or prior assumptions or frameworks of meaning. In this respect, it has some association with ‘experiential’ compared with ‘narrative’ modes of being as described in research into the impacts of meditation [

52]. The focus becomes increasingly towards the minutiae—our impulses and judgements that may have previously passed under the radar of awareness.

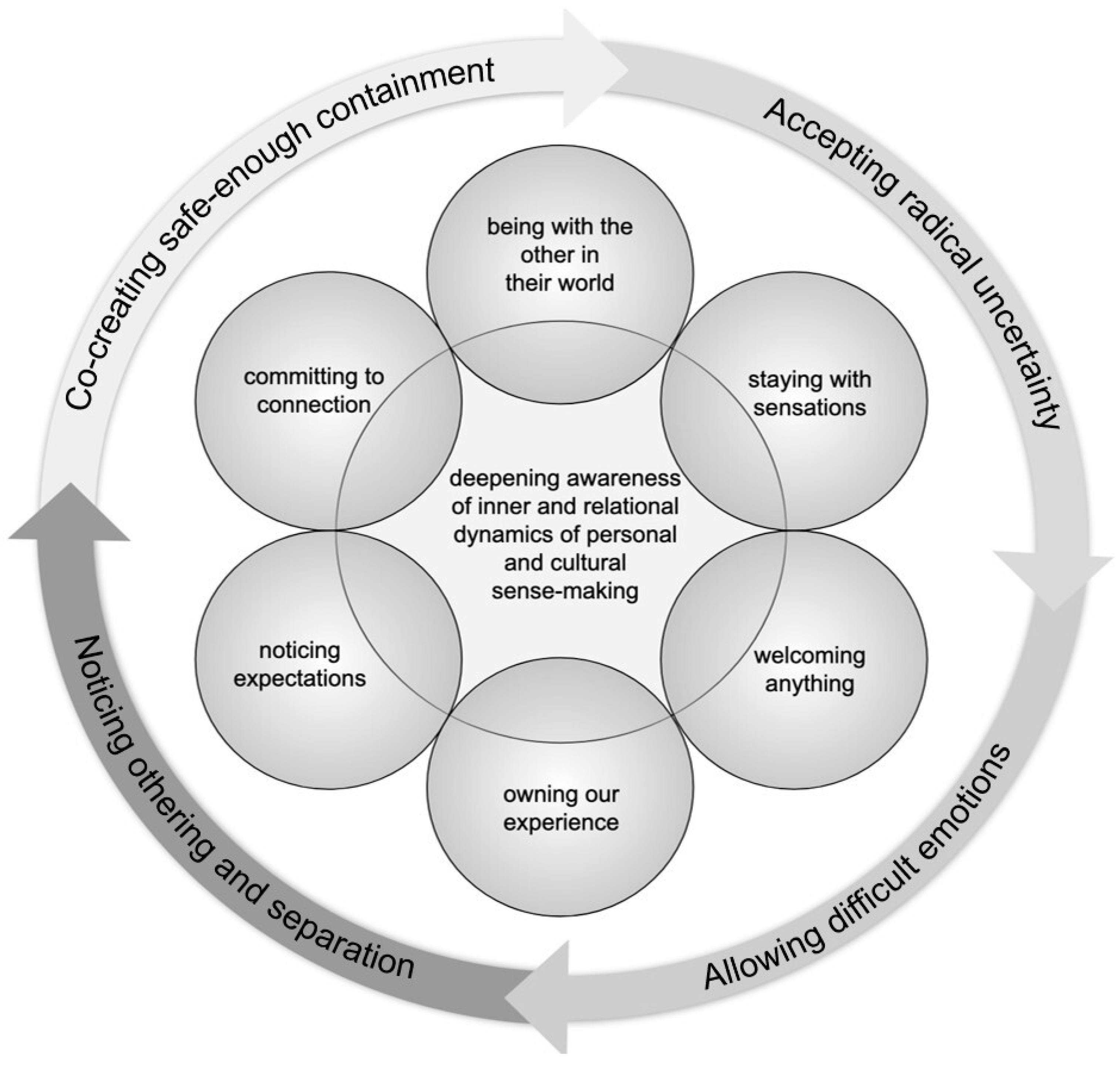

We have developed this practice through the adaptation of some existing modalities (that we discuss below). The way we present the practice to participants is with a set of six principles that guide emergent dialogue:

Committing to connection—with ourselves, each other, all that arises in the present moment, and the wider fields of existence, including what is described as the natural world and the metaphysical.

Staying with sensations—noticing the sensations and emotions as they arise in the body in the present moment and allowing them to be expressed and acknowledged.

Welcoming anything—we trust that whatever emotions and sensations are arising through our interactions are here to enable us and the group to shift into greater awareness.

Owning our experience—by recognising that although our emotions and thoughts about others and situations might relate to the outer reality, we cannot know that, and instead we witness this inner process for information on ourselves, especially when feeling triggered by others.

Being with the other in their world—while others are sharing, we explore what it might be like to be this person, and we ask questions that allow us to understand their present experience better, rather than seeking to influence them or express our own stories of reality.

Noticing expectations—by recognising that culturally-shaped expectations influence our experience of self, others, the gathering, and the topics being addressed, we can become more conscious of moments of how culture influences sour relating.

This practice is similar to, and has evolved from, other modalities known as Authentic Relating (

https://authenticrelating.co/, accessed on 4 March 2021), Circling (

https://www.circlingeurope.com, accessed on 4 March 2021), and ‘Focusing’ in psychotherapy [

53], and also the modern Buddhist practice of Insight Dialogue [

54]. It is also influenced by Bohmian dialogue, so it is not goal oriented, but invites “…a stream of meaning flowing among and through us and between us… [which makes] possible a flow of meaning in the whole group, out of which will emerge some new understanding… this shared meaning is the ‘glue’ or ‘cement’ that holds people and societies together” [

55].

The practice invites us to slow down, so we can become continually attentive and curious about our inner world, in a similar way to what occurs within individuals during insight meditation (vipassana). That helps reveal to us our habitual entanglements of either perception or sensations, with our emotions and thoughts. Once these different phenomena and their entanglements are noticed, we can choose to act less habitually. Within a culture preoccupied by urgency and busy-ness, this slowing down in order to notice and acknowledge the ways in which we make sense of experience according to prior assumptions, can reveal—sometimes painfully—how we recreate and reinforce cultural bias and discrimination in micro-moments of relating. Put simply, not to allow time and space for acknowledging the micro-violences that happen unconsciously in our relating is how systemic inequalities are transferred between the personal and the cultural, and vice versa.

Given the way that our environmental predicament is being perpetuated within an overmodern culture, helping each other to look at the assumptions, framings and narratives of that dominant culture means that we have a better chance of not unconsciously acting from them in ways that cause further harm. In particular, we have witnessed how the mental habits of the ideology of e-s-c-a-p-e occur when people seek to shift really difficult emotions as they consider the likelihood of early and widespread suffering. For instance, many people initially express ideas that they think will give their own children a better chance of safety, even if those ideas might harm the lives of others. If they reflect on the emotions involved, express them in a process of disentangling the emotions from the thoughts about what they might imply, that might reduce the likelihood of their instincts being manipulated by people and institutions in ways that create further harm.

One of the ways in which Deep Relating is distinct from other similar practices is that ‘collapse awareness’ is explicitly present in the space and named by facilitators. If the facilitator seems at all blasé or numb about the issue of societal disruption or collapse, then this can convey an unhelpful tone. Instead, it is important to remove any barriers to participants’ full expression around this topic. That does not mean this topic will arise during a period of Deep Relating, but the extended notion of “committing to connection” means we begin by explicitly recognising the interconnected context within which we meet. To foreground the situation of humanity and planet Earth, a facilitator can offer an introductory reading that might reconnect people emotionally with the unfolding situation. That could be a news item, piece of prose or poetry.

Another way that Deep Relating is different from similar practices is the invitation into criticality—a critically conscious engagement with the stories we participate in that co-create the destructive overmodern era we live in today. On the one hand, the practice invites the surfacing of unconscious patterns within dominant discourse. These are the mental habits that can result in othering and e-s-c-a-p-e, and so Deep Relating is useful for seeking to avoid making matters worse as we explore responses to unfolding disruption. There is an emphasis on somatic and affective dimensions being as important as the cognitive or narrative; dialogue is emergent and not outcome-oriented; and that (ostensibly at least) anything is welcomed rather than there being rule-governed modes of participation. However, the presence of these ingredients is not sufficient to invite criticality. We have witnessed similar modalities which are framed as a way of revealing one’s ‘true’ or ‘authentic’ self, a narrative which can amplify, rather than lessen, a sense of exceptionalism and entitlement, typical of what Foucault called the “Californian cult of the self” [

56] (p. 362). That can be particularly attractive for some people whose anticipation of personal mortality and a loss of past identity in the face of collapse leads them to choose narratives, experiences and communities that offer to support them in the least complicated (or most enjoyable) manner. If a ‘spiritual bypass’ response to lessening one’s conformity with society drives people’s response, then there may even be a suppression of attention to questions of complicity and solidarity. Not only would that reduce opportunities for them to learn, engage and reduce contributions to unnecessary harm, it is an exclusionary narrative that might therefore align with the tendencies towards repressive politics that are occurring in many countries. Therefore, a key difference with the way some facilitators use similar modalities is that Deep Relating (see

Figure 2) is not aiming towards the transformation of difficult emotions. Instead, the aim is to be able to accept difficult emotions, so that aversion to them does not influence the quality of discussion and any future decision making.

In the past, we have witnessed hosts of similar processes embodying, enabling and legitimising subtle enactments of currently dominant discourse. Therefore, if facilitators are not holding space with some of the ‘critical consciousness’ we describe in this article, there is a risk of allowing or inadvertently reinforcing dominant narratives—about power, domination, entitlement, and progress—which will hinder deep engagement with the situation of societal disruption and collapse. To help avoid this situation, Deep Relating processes can offer a sixth principle, which is an invitation for participants to be curious about the deeper cultural stories that might exist within themselves and the group. The principle of ‘noticing expectations’ invites participants to witness the assumptions, frames and narratives that might be widely accepted, assumed or absent within a particular gathering. To invite attention to this principle, useful questions from either a facilitator or participant include.

“Might you/I have some expectations about someone/something and, if so, where might these come from?”

“What assumptions might you/I be making here?”

“What else must be true for you/me to think or feel what you/I am experiencing right now?”

4.5. Benefits of These Principles and Practices

Within the group processes themselves, we saw initial evidence that the facilitation process and principles outlined in this paper helped to undo some of the deeply rooted patterns of thinking and relating that we identified as causal of our predicament. These patterns we summarised earlier as various forms of ‘othering.’ Whether othering humans and nature, or aspects of ourselves, this has given rise to cultural norms that have been labelled as patriarchy, anthropocentrism, and colonialism. Such ‘othering’ also provided the foundation for the ideology of e-s-c-a-p-e which pervades modernity. None of us can discover how to think and act in ways different to the existing culturally determined patterns unless we first begin to notice those patterns. The facilitated processes brought attention to such patterns by enabling participants to observe the processes of othering that were occurring within themselves, in the form of judgements about other people, or their own ideas and emotions that they were experiencing as unwelcome. We experienced this greater awareness of othering-in-the-moment ourselves, and many other participants reported it to us. Although the systems we critique in this paper are supported and reproduced by all manner of resources, rules, laws, and institutions, bringing attention to the reproduction of such systems within ourselves is a contribution to their dismantling. It would be an interesting inquiry in future to explore how such shifts might also affect pro-environmental behaviours, such as reducing carbon emissions, whether as individuals, professionals, or politically active citizens.

How might the loosening of these patterns through the facilitation processes outlined in this paper help people respond positively to increasing societal disruptions due to environmental change? To answer that, more research on the implications for people’s lives outside of the facilitated processes will be necessary, as well as the implications of any decisions made in meetings that included some elements of this Deep Adaptation facilitation. Our hypothesis is that it will reduce the amplification of unhelpful responses to future changes enforced on us from societal disruptions. That is because one aspect of such disruption is the interruption of our assumed worldviews and belief systems. if we feel confused, afraid and isolated, we are more likely to adopt narratives that appear to offer to reduce stress or shift the emotions of sadness and fear into other ones such as anger and blame. To bring more attention to that inner process, and thus be more curious and engaged with a worrying and constantly evolving situation, we will all benefit from support for expressing and processing our emotions prior to any decisions or actions.