Government Spending and Economic Growth: A Cointegration Analysis on Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

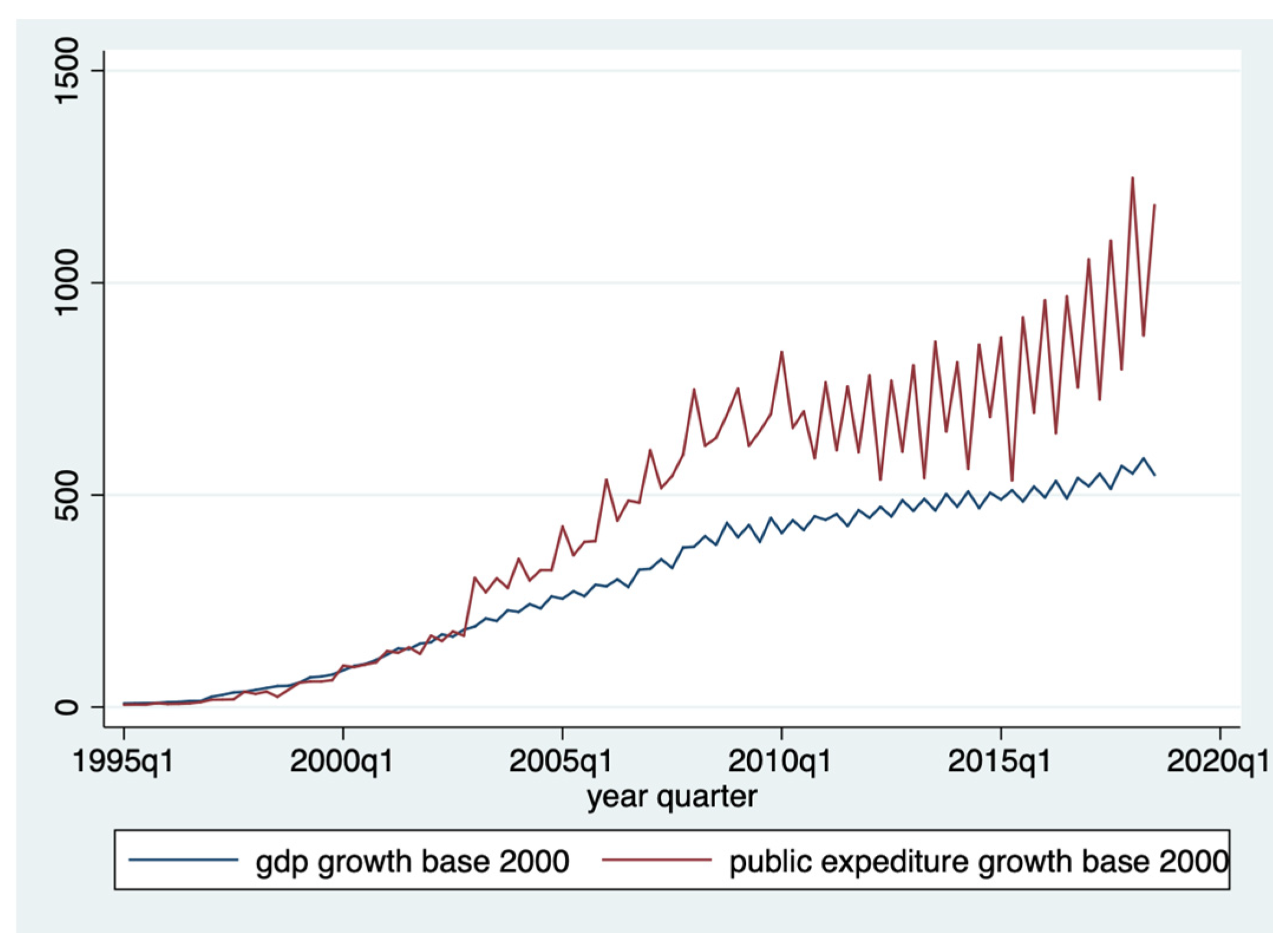

3. Data and Method

3.1. Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) Test

3.2. DF-GLS Test

3.3. Phillipps–Perron Test

3.4. Ng Perron Test

3.5. Johansen Cointegration Analysis

3.6. Granger Causality Analysis

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Cointegration Analysis

4.2. Granger Testing According to Toda and Yamamoto Approach

4.3. Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wagner, A. Finanzwissenschaft; C.F. Winter: Leipzig, Germany, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1776; Volume one. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, A.T.; Wiseman, J. The Growth of Public Expenditure in the United Kingdom; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 1967; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrave, R.A. Cost-benefit analysis and the theory of public finance. J. Econ. Lit. 1969, 7, 797–806. [Google Scholar]

- Michas, N.A. Wagner’s Law of public expenditures: What is the appropriate measurement for a valid test? Public Financ Financ. Publiques 1975, 30, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, A.J. Wagner’s law: An econometric test for Mexico, 1925–1976. Natl. Tax J. 1980, 33, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R. Poverty in Bangladesh: A Consequence of and a Constraint on Growth. Bangladesh Dev. Stud. 1990, 18, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, F.L. Public Expenditures in Communist and Capitalist Nations; RD Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, I.J. Empirical testing of Wagner’s law-technical note. Public Finance Financ. Publiques 1968, 23, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.P. Public Expenditure and Economic Growth a Time-Series Analysis. Public Finance Financ. Publiques 1967, 22, 423–454. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, M.; Abbas, Q. Wagner’s law in Pakistan: Another look. J. Econ. Int. Finance 2009, 2, 012–019. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, J.M. The General Theory of Money, Interest and Employment; Macmillan: London, UK, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, R. Government size and economic growth: A new framework and some evidence from cross-section and time-series data. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, S.M.; Kwan, A.C.; Sahni, B.S. Cointegration and Wagner’s hypothesis: Time series evidence for Canada. Appl. Econ. 1996, 28, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.M.; Hutton, P.A. On the casual relationship between government expenditures and national income. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1990, 72, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Sahni, B.S. Causality between public expenditure and national income. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1984, 66, 630–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J.R.; Keleher, R.E.; Russek, F.S. The scale of government and economic activity. South. Econ. J. 1990, 13, 142–183. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, D. Government expenditure and economic growth: A cross-country study. South. Econ. J. 1983, 49, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, D. Government and economic growth in the less developed countries: An empirical study for 1960–1980. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 1986, 35, 35–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrakdar, S.; Demez, S.; Yapar, M. Testing the Validity of Wagner’s Law: 1998–2004, The Case of Turkey. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, E.; Yavuz, H. New Public Expenditure and Growth: The period 1996–2008 in Turkey. J. Finance 2010, 158, 164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, P. Causality between Public Expenditure and Economic Growth: The Indian Case. Int. J. Econs. Mgmt. 2013, 7, 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Bohl, M.T. Some international evidence on Wagner’s Law. Public Finance Financ. Publiques 1996, 51, 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Chletsos, M.; Kollias, C. Testing Wagner’s law using disaggregated public expenditure data in the case of Greece: 1958–93. Appl. Econ. 1997, 29, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, K.H. Public investment and private capital formation in a vector error-correction model of growth. Appl. Econ. 1998, 30, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, J.; Iqbal, A.; Siddiqi, M.W. Cointegration-causality analysis between public expenditures and economic growth in Pakistan. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 13, 556–565. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Faris, A.F. Public expenditure and economic growth in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Y.; Tang, J.H.; Lin, E.S. The impact of government expenditure on economic growth: How sensitive to the level of development? J. Policy Model. 2010, 32, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, N.; Hansen, P. Health care spending and economic output: Granger causality. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2001, 8, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.; Dhawan, U.; Lee, H.Y. Testing Wagner versus Keynes using disaggregated public expenditure data for Canada. Appl. Econ. 1999, 31, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighodaro, C.A.; Oriakhi, D.E. Does the Relationship between Government Expenditure and Economic Growth Follow Wagner’s Law in Nigeria. Ann. Univ. Petrosani. Econ. 2010, 10, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Bader, S.; Abu-Qarn, A.S. Government expenditures, military spending and economic growth: Causality evidence from Egypt, Israel, and Syria. J. Policy Model. 2003, 25, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quah, D. Empirical cross-section dynamics in economic growth. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1993, 37, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalles, J. Wagner’s law and governments’ functions: Granularity matters. J. Econ. Stud. 2019, 46, 446–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, M.A. A bound testing analysis of Wagner’s law in Nigeria: 1970–2006. Appl. Econ. 2011, 43, 2843–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, R. Wagner’s hypothesis in time-series and cross-section perspectives: Evidence from “real” data for 115 countries. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1987, 69, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afxentiou, P.C.; Serletis, A. Government expenditures in the European Union: Do they converge or follow Wagner’s Law? Int. Econ. J. 1996, 10, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.I.; Gordon, D.V.; Akuamoah, C. Keynes versus Wagner: Public expenditure and national income for three African countries. Appl. Econ. 1997, 29, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abizadeh, S.; Yousefi, M. An empirical analysis of South Korea’s economic development and public expenditures growth. J. Socio Econ. 1998, 27, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdigen, M.; Cetintas, H. Causality between public expenditure and economic growth: The Turkish case. J. Econ. Soc. Res. 2004, 1, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Başar, S.; Aksu, H.; Temurlenk, M.S.; Polat, Ö. Government Spending and Economic Growth Relationship in Turkey: A Bound Testing Approach. Atatürk Üniv. Sos. Bilimler Enstitüsü Derg. 2009, 13, 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Rauf, A.; Qayum, A.; Zaman, K.U. Relationship between public expenditure and national income: An empirical investigation of Wagner’s law in case of Pakistan. Acad. Res. Int. 2012, 2, 533. [Google Scholar]

- Jiranyakul, K.; Brahmasrene, T. The relationship between government expenditures and economic growth in Thailand. J. Econ. Econ. Educ. Res. 2007, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, R.P. Wagner’s Law: Is it Valid in India? IUP J. Public Finance 2007, 2, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Magazzino, C. Wagner’s Law in Italy: Empirical Evidence from 1960 to 2008; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.F.; Chrsquo, K.S. The Granger causality between health expenditure and income in Southeast Asia economies. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 6814–6824. [Google Scholar]

- Nurudeen, A.; Usman, A. Government expenditure and economic growth in Nigeria, 1970–2008: A disaggregated analysis. J. Bus. Econ. 2010, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, E.; Lai, K.S. Government spending and economic growth: The G-7 experience. Appl. Econ. 1994, 26, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, C. Government spending and economic growth: Econometric evidence from the South Eastern Europe (SEE). J. Econ. Soc. Res. 2009, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dritsaki, C.; Dritsaki, M. Government expenditure and national income: Causality tests for twelve new members of EE. Rom. Econ. J. 2010, 13, 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Braşoveanu, L.O. The impact of defense expenditure on economic growth. Rom. J. Econ. Forecast. 2010, 148, 148–167. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.C.; Huang, B.N.; Yang, C.W. Military expenditure and economic growth across different groups: A dynamic panel Granger-causality approach. Econ. Model. 2011, 28, 2416–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzuner, G.; Bekun, F.V.; Akadiri, S.S. Public Expenditures and Economic Growth: Was Wagner Right? Evidence from Turkey. Acad. J. Econ. Stud. 2017, 3, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sagdic, E.N.; Sasmaz, M.U.; Tuncer, G. Wagner versus Keynes: Empirical Evidence from Turkey’s Provinces. Panoeconomicus 2020, 67, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilgan, E.; Kilic, D.; Ertugrul, H.M. The dynamic relationship between health expenditure and economic growth: Is the health-led growth hypothesis valid for Turkey? Eur J. Health Econ. 2017, 18, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, U.; Habimana, O. Military Spending and Economic Growth in Turkey: A Wavelet Approach. Defence Peace Econ. 2021, 32, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunc, O.F.; Aydın, C. The relationship between optimal size of government and economic growth: Empirical evidence from Turkey, Romania and Bulgaria. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 92, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingxiao, W.A.N.G.; Peculea, A.D.; Xu, H. The relationship between public expenditure and economic growth in Romania: Does it obey Wagner’s or Keynes’s Law? Theor. Appl. Econ. 2016, 23, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. From Uneven Growth to Inclusive Development: Romania’s Path to Shared Prosperity. Systematic Country Diagnostic; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29864 (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Bostan, I.; Onofrei, M.; Popescu, C.; Lupu, D.; Firtescu, B. Efficiency and Corruption in Local Counties: Evidence from Romania. Lex Localis 2018, 16, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, M.; Lazányi, K.; Sopková, G.; Dobeš, K.; Balcerzak, A.P. Determinants of economic growth in V4 countries and Romania. J. Compet. 2017, 9, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INS. Quarterly Gross Domestic Product—Seasonally Adjusted Series. National Institute of Statistics Portal. 2018. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/en/content/gross-domestic-product (accessed on 11 December 2019).

- INS. Collective Final Consumption Expenditure. National Institute of Statistics Portal. 2018. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/en/content/gross-domestic-product (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Johansen, S. Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 1988, 12, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. Identifying restrictions of linear equations with applications to simultaneous equations and cointegration. J. Econ. 1995, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J. Co-Investigated Variables and Error-Correction Models; Working Paper; University of California: San Diego, CA, USA, 1983; pp. 83–113. [Google Scholar]

- Toda, H.Y.; Yamamoto, T. Statistical inference in Vector Autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. J. Econ. 1995, 66, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Lin, C.F. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J. Econ. 2002, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo, J.; Pitarakis, J.Y. Specification via model selection in vector error correction models. Econ. Lett. 1998, 60, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, A.; Salvador, M. Selecting the Rank of the Cointegration Space and the Form of the Intercept Using an Information Criterion. Econ. Theory 2002, 18, 926–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J.M.; Tullock, G. The Calculus of Consent; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1962; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

| Sample: 1997q1–2018q3 | Number of obs = 87 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lag | LL | LR | df | p | FPE | AIC | HQIC | SBIC |

| 0 | −1107.01 | 4.0 × 108 | 25.4945 | 25.5174 | 25.5512 | |||

| 1 | −860.603 | 492.82 | 4 | 0.000 | 1.5 × 106 | 19.9219 | 19.9904 | 20.092 |

| 2 | −780.768 | 159.67 | 4 | 0.000 | 269,165 | 18.1786 | 18.2927 | 18.462 |

| 3 | −776.194 | 9.149 | 4 | 0.057 | 265,752 | 18.1654 | 18.3252 | 18.5622 |

| 4 | −742.95 | 66.488 | 4 | 0.000 | 135,785 | 17.4931 | 17.6985 | 18.0033 |

| 5 | −719.798 | 46.304 | 4 | 0.000 | 87,534.1 | 17.0528 | 17.3039 | 17.6764 * |

| 6 | −713.294 | 13.008 * | 4 | 0.011 | 82,785.6 | 16.9953 | 17.292 * | 17.7322 |

| 7 | −708.593 | 9.4013 | 4 | 0.052 | 81,662.7 * | 16.9791 | 17.3215 | 17.8295 |

| 8 | −704.581 | 8.0248 | 4 | 0.091 | 81,903.1 | 16.9789 * | 17.3669 | 17.9426 |

| Exgov-0 | Gdp-0 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Critical Value | Statistic | Prob | Stationarity | Test | Critical Value | Statistic | Prob | Stationarity |

| ADF | −3.2595 | 0.0795 | non-stat | ADF | −2.8794 | 0.1739 | non-stat | ||

| 1% | −4.0586 | non-stat | 1% | −4.0586 | non-stat | ||||

| 5% | −3.4583 | non-stat | 5% | −3.4583 | non-stat | ||||

| 10% | −3.1551 | stat | 10% | −3.1551 | non-stat | ||||

| DF_GLS | −3.0198 | non-stat | DF_GLS | −2.652 | non-stat | ||||

| 1% | −3.6028 | non-stat | 1% | −3.6028 | non-stat | ||||

| 5% | −3.0492 | non-stat | 5% | −3.0492 | non-stat | ||||

| 10% | −2.758 | stat | 10% | −2.758 | non-stat | ||||

| PP | −3.2993 | 0.0727 | non-stat | PP | −3.0786 | 0.1175 | non-stat | ||

| 1% | −4.0586 | non-stat | 1% | −4.0586 | non-stat | ||||

| 5% | −3.4583 | non-stat | 5% | −3.4583 | non-stat | ||||

| 10% | −3.1551 | non-stat | 10% | −3.1551 | non-stat | ||||

| NG-Perron | −15.2214 | non-stat | NG-Perron | −12.2895 | non-stat | ||||

| 1% | −23.8 | non-stat | 1% | −23.8 | non-stat | ||||

| 5% | −17.3 | non-stat | 5% | −17.3 | non-stat | ||||

| 10% | −14.2 | stat | 10% | −14.2 | non-stat | ||||

| Sexgov-1 | Sgdp-1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Critical Value | Statistic | Prob | Stationarity | Test | Critical Value | Statistic | Prob | Stationarity |

| ADF | −10.11 | 0 | stat | ADF | −9.5333 | 0 | stat | ||

| 1% | −4.0597 | stat | 1% | −4.0597 | stat | ||||

| 5% | −3.4588 | stat | 5% | −3.4588 | stat | ||||

| 10% | −3.1554 | stat | 10% | −3.1554 | stat | ||||

| DF_GLS | −10.22 | stat | DF_GLS | −9.6322 | stat | ||||

| 1% | −3.6066 | stat | 1% | −3.6066 | stat | ||||

| 5% | −3.0524 | stat | 5% | −3.0524 | stat | ||||

| 10% | −2.761 | stat | 10% | −2.761 | stat | ||||

| PP | −10.14 | 0 | stat | PP | −9.5333 | 0 | stat | ||

| 1% | −4.0597 | stat | 1% | −4.0597 | stat | ||||

| 5% | −3.4588 | stat | 5% | −3.4588 | stat | ||||

| 10% | −3.1554 | stat | 10% | −3.1554 | stat | ||||

| NG-Perron | −46.31 | stat | NG-Perron | −46.4991 | stat | ||||

| 1% | −23.8 | stat | 1% | −23.8 | stat | ||||

| 5% | −17.3 | stat | 5% | −17.3 | stat | ||||

| 10% | −14.2 | stat | 10% | −14.2 | stat | ||||

| Trend: trend Number of obs = 87 Sample: 1997q1–2018q3 Lags = 8 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| maximum rank | parms | LL | eigenvalue | trace statistic | 5% critical value |

| 0 | 32 | −704.92957 | . | 8.5487 * | 18.17 |

| 1 | 35 | −700.71974 | 0.09224 | 0.1291 | 3.74 |

| 2 | 36 | −700.6552 | 0.00148 | ||

| Trend: trend Number of obs = 87 Sample: 1997q1–2018q3 Lags = 8 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| maximum rank | parms | LL | eigenvalue | SBIC | HQIC | AIC |

| 0 | 32 | −704.92957 | . | 17.84791 * | 17.30613 * | 16.94091 |

| 1 | 35 | −700.71974 | 0.09224 | 17.90513 | 17.31256 | 16.9131 |

| 2 | 36 | −700.6552 | 0.00148 | 17.95498 | 17.34548 | 16.9346 |

| Selection-Order Criteria Sample: 1997q3–2018q3 | Number of obs = 85 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lag | LL | LR | df | p | FPE | AIC | HQIC | SBIC |

| 0 | −1080.35 | 3.9 × 108 | 25.4671 | 25.4902 | 25.5245 | |||

| 1 | −841.843 | 477.01 | 4 | 0.000 | 1.6 × 106 | 19.9492 | 20.0186 | 20.1217 |

| 2 | −764.434 | 154.82 | 4 | 0.000 | 281,111 | 18.222 | 18.3376 | 18.5094 |

| 3 | −760.134 | 8.6012 | 4 | 0.072 | 279,263 | 18.2149 | 18.3767 | 18.6172 |

| 4 | −727.152 | 65.963 | 4 | 0.000 | 141,327 | 17.533 | 17.7411 | 18.0503 |

| 5 | −705.211 | 43.884 | 4 | 0.000 | 92,781.3 | 17.1108 | 17.3651 | 17.7431 * |

| 6 | −698.812 | 12.798 | 4 | 0.012 | 87,857.8 | 17.0544 | 17.3549 * | 17.8016 |

| 7 | −694.25 | 9.1227 | 4 | 0.058 | 86,933.3 | 17.0412 | 17.3879 | 17.9033 |

| 8 | −690.335 | 7.8298 | 4 | 0.098 | 87,409.6 | 17.0432 | 17.4362 | 18.0202 |

| 9 | −684.414 | 11.842 * | 4 | 0.019 | 83,916.7 * | 16.998 * | 17.4372 | 18.09 |

| 10 | −681.756 | 5.3163 | 4 | 0.256 | 87,088 | 17.0296 | 17.515 | 18.2365 |

| lag | chi2 | df | Prob > chi2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.0611 | 4 | 0.39779 |

| 2 | 2.9691 | 4 | 0.56301 |

| 3 | 5.4116 | 4 | 0.24761 |

| 4 | 2.4621 | 4 | 0.65143 |

| 5 | 2.8816 | 4 | 0.57783 |

| 6 | 4.6867 | 4 | 0.32098 |

| 7 | 4.5915 | 4 | 0.33184 |

| 8 | 4.7217 | 4 | 0.31706 |

| 9 | 4.1258 | 4 | 0.38924 |

| Test for exgov Granger Causality to gdp | Test for gdp Granger Causality to exgov |

|---|---|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popescu, C.C.; Diaconu, L. Government Spending and Economic Growth: A Cointegration Analysis on Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6575. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126575

Popescu CC, Diaconu L. Government Spending and Economic Growth: A Cointegration Analysis on Romania. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6575. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126575

Chicago/Turabian StylePopescu, Cristian C., and Laura Diaconu (Maxim). 2021. "Government Spending and Economic Growth: A Cointegration Analysis on Romania" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6575. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126575

APA StylePopescu, C. C., & Diaconu, L. (2021). Government Spending and Economic Growth: A Cointegration Analysis on Romania. Sustainability, 13(12), 6575. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126575