1. Introduction

Building strong customer relationships and loyalty is increasingly important for companies in today’s rapidly changing marketing environment [

1,

2]. Developing sustained brand loyalty has attained such a staggering attention because it helps firms in developing advantages that are viable in the markets [

3]. It has been observed that the attainment of brand loyalty is based on programs related to the corporate marketing [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Typically, brand loyalty is reflected in how customers evaluate the company’s outlook towards the product evaluation and consumer-brand relations [

8,

9,

10]. Certain studies have argued that companies should give their brand message while considering social and environmental problems, and sell their products to consumers [

11,

12]. Strategies focused on common issues increase the interest of consumers in buying the products or services from such companies. Given that modern societies require companies to be responsible and ethical to their stakeholders. Therefore, the maintenance of consumer relationships and brand loyalty are not easy to attain and pose major challenges to firms in today’s marketing environment.

Ethical marketing strategies have been studied for nearly all business areas which are formulated to gain a competitive advantage [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. A company’s ethical marketing practices affect the daily routine of consumer activity. Every company’s ethical marketing practices are closely related to the purchase of products or services, regardless of whether it is conscious of consumer purchasing power strengths and weaknesses. The importance of ethics in the advancement of business sustainability, and general marketing issues (including product safety, price tags and advertising) has duly been recognized by corporate managers and vendors [

18]. As an outcome, an economic behavior, whether ethical or non-ethical, is inherently linked with a company’s overall reputation and assessment, and stresses the fundamental factors in keeping the company competitive on the market [

19,

20,

21].

Despite the apparent significant role of ethical marketing practices on relationship building, product evaluation, and high-brand loyalty, only a few studies have examined the effects of extended marketing mix elements (viz. product, price, place, promotion, person, physical evidence, and packaging) on consumption and brand loyalty [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Moreover, ethical marketing practice plays a significant role in improving consumer-firm ties, product assessment, and brand loyalty [

27,

28,

29]. Only a few studies have examined the role of ethical marketing mix elements on such attitudinal and behavioral outcomes [

18,

30,

31]. Moreover, the literature has explored the effects of extended marketing mix elements on value-adding product sustainability and customer-brand relationship sustainability in B2C transactions from an ethical marketing perspective [

32,

33]. Nevertheless, the focus of the literature was on the 4Ps of the marketing mix in this regard. Hence, the present study highlighted this literature gap and contributed by exploring the role of extended marketing mix with the 7Ps approach from an ethical marketing perspective. The findings of this study would be attractive for the companies to build an ethically rich culture, adopting the proposed extended marketing mix with the 7Ps approach that offers fair and trust-oriented transactions. Such an ethically sound approach can help companies facilitate strong relationship building and brand loyalty, which eventually offers them a competitive advantage to survive and sustain for the long term.

3. Conceptual Model and Hypothesis Development

Marketing mix strategy explains how a company offers services and products to satisfy the requirements of divisions of the target market [

82]. Marketing strategy with ethical perspectives concern with the righteous behavior and high minded beliefs that enlighten the venture which is marketable so that marketing strategies are applicable for ethical deliberations. Problems in ethical marketing take place further continually in such zones where legitimate acts can be sometimes immoral or in which the lawfulness or morality of actions is undetermined [

1]. In order to create positive effects on consumers and brands relationship sustainability, the role of marketing ethics has become progressively important because of this uncertainty in those regions [

82,

83]. For increasing the trust between multiple stakeholders of the company (including customers), the superior level of ethical authority leads [

80,

81].

Consumers and brands interact with each other continually [

84]. The relational value that a company offers through ethical marketing practices determinses the intellectual and psychological procedure that enhances the interaction between customers and the brand on a sustainable basis. Correspondingly, in this study we deal with a proximity point between the ethical marketing practice and customer value-brand relationship sustainability because consumers estimate the brand and builds the relationship sustainability through some processes in which experience and interaction with the brands occur. Extended marketing mix often serves as the first contact impression through which customers know a brand and come in terms with it [

11,

16]. Consumers observe the ethical marketing practices because it is the most visible in a brand’s manifold schemes and play important role in shaping consumer perceptions towards a brand [

85,

86,

87,

88].

Prior studies reveal that ethical problems in marketing have involved issues pertaining to product safety and quality, price fixing, deceptive promotions, illegal product placement, child labor and unfair person treatment, misleading information provided through fake physical evidence and packaging [

7,

11,

12,

63]. Such ethical issues revolving around fairness and human resource management affect subjective evaluations of product, and relationship value of customers [

11]. Fraudulent prices are main cause of misleading the consumer’s basic features to purchase, so that is why to improve the relationship between brands and consumers, right prices are needed to be set in the marketplace. Information about product should be truthful to maintain the relationship with customer because negative effects of displays could lead to unreasonable decisions by consumers [

11,

37,

40]. It is suggested that ethical marketing practices related to the marketing mix elements could lead to favorable decisions by consumers which may further derive positive outcomes for the company/brand. Ethical marketing practices results in a more socially responsible and sensitive business community which eventually has the potential (in both the short and long run) to benefit the society as a whole [

55,

71]. Building upon these arguments, it is suggested that positive relationship occurs through a company’s/brand’s ethical marketing practice and their customer value-brand relationship sustainability. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

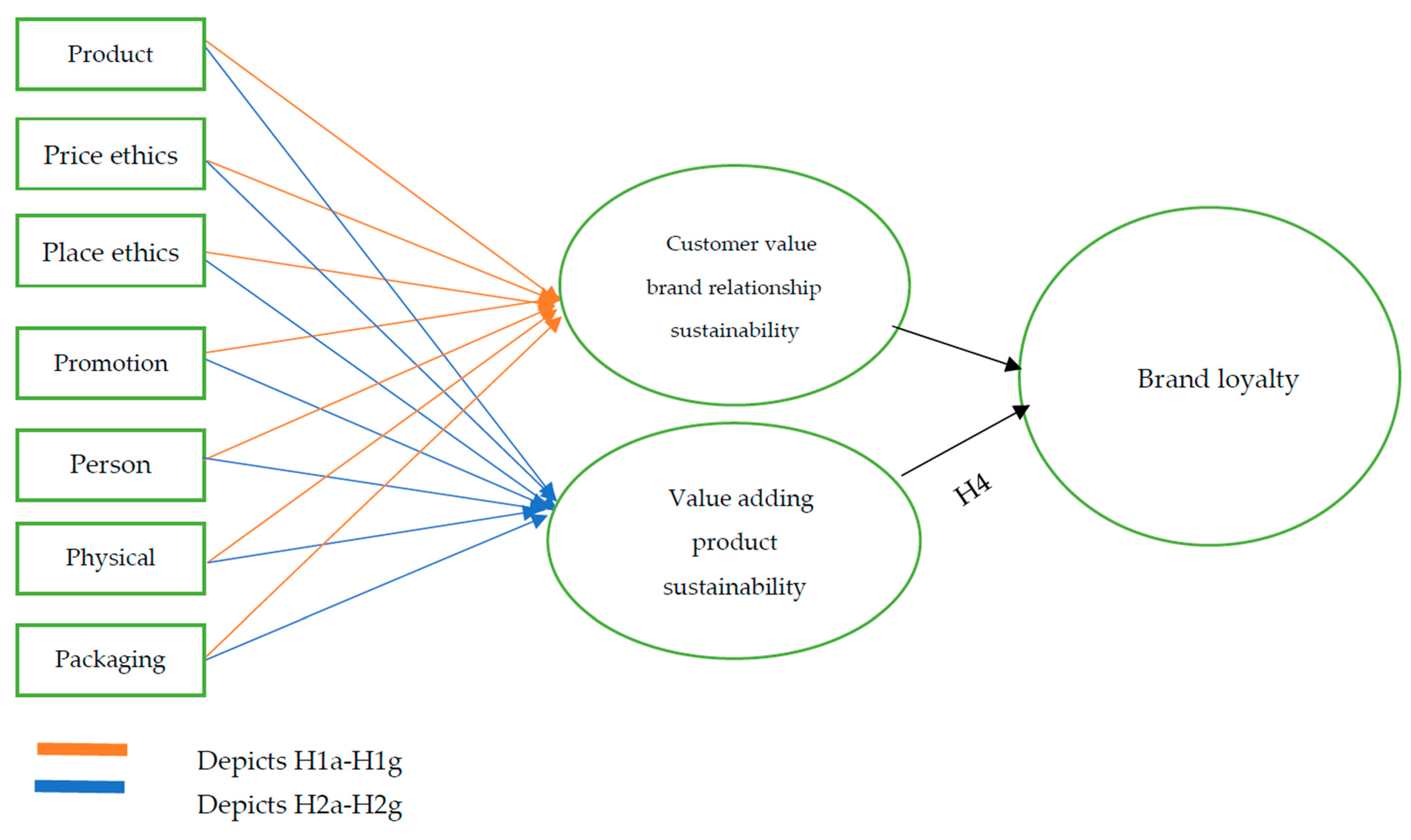

Hypothesis 1a (H1a). Product-associated ethics shows a positive effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b). Price-associated ethics shows a positive effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability.

Hypothesis 1c (H1c). Place-associated ethics shows a positive effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability.

Hypothesis 1d (H1d). Promotion-associated ethics shows a positive effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability.

Hypothesis 1e (H1e). Person-associated ethics shows a positive effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability.

Hypothesis 1f (H1f). Physical evidence-associated ethics shows a positive effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability.

Hypothesis 1g (H1g). Packaging-associated ethics shows a positive effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability.

Value-adding product sustainability should persuade customer’s wishes and demands in which safety of the product, well-being levels and habitats take place. The brands that convey ethical values with responsible behavior are the brands which are surrounded by high quality products and are chosen by the customer. Regarding the idea of product sustainability, this is referred to as the personalized sustainability that customers expect in the product. The brand that organizes the responsible actions for marketing in their products and services, receive warm respect and trust from their customers as well as from their shareholders [

89,

90,

91]. Companies can achieve sustained benefits and trust from their customers only when their deals and agreements are based on the ethical marketing practices with their interested parties. As an outcome, customers prefer brands that are perceived to deliver ethical values and behave responsibly [

89]. Based on these arguments, we suggest a positive association between a brand’s ethical marketing practices with their value adding product sustainability. So, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a). Product-associated ethics shows a apositive effect on value adding product sustainability.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b). Price-associated ethics shows a positive effect on value adding product sustainability.

Hypothesis 2c (H2c). Place-associated ethics shows a positive effect on value adding product sustainability.

Hypothesis 2d (H2d). Promotion-associated ethics shows a positive effect on value adding product sustainability.

Hypothesis 2e (H2e). Person-associated ethics shows a positive effect on value adding product sustainability.

Hypothesis 2f (H2f). Physical-associated ethics shows a positive effect on value adding product sustainability.

Hypothesis 2g (H2g). Packaging-associated ethics shows a positive effect on value adding product sustainability.

Customers always observe the brand’s marketing strategies because it is one of the most perceptible fields [

92,

93,

94]. Moreover, customers nudge the brand by applying mutual and emotional standards to activities, companies and stories when they chose a brand. Later on, a customer value-brand relationship builds up. Customers mostly evaluate the brand and prefers based on their experiences rather than the particular characteristics of the product. Brand loyalty also has a major role in the establishment of the brand’s asset. Previous studies show that the brand loyalty and sustainability improve focusing with the B2C connection perfectly [

67,

79]. Maintaining the high quality of customer-brand relationship is a major aim of branding because relationship between customer and brand provides a sustainable competitive advantage to the companies.

Previous studies reveal that customers are always satisfied with the positive effects of product quality [

11,

38]. Also, the value of the product is intimately significant to the customer’s contentment and trust because product’s value can be seen as the dissimilarity between general and unexplored standards. When customers build a relationship with the brand due to its favorable brand experience and the sustained product value, it drives customers to develop loyalty intentions and stay with the brand for a longer period of time [

2,

54,

60]. Therefore, value-brand relationship sustainability and value adding product sustainability play a dominant role on brand loyalty [

89]. Hence, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Customer value-brand relationship sustainability have a positive effect on brand loyalty.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Value adding product sustainability has a positive effect on brand loyalty.

Based on the above hypotheses, we developed our research model as shown in

Figure 1 below.

6. Discussion

This study aimed at investigating the elements of marketing mix and brand relationship from an ethical marketing perspective. To empirically validate our proposed conceptual model, sixteen hypotheses were tested in the current study, of which thirteen revealed a positively significant relationship and were supported. The remaining three hypotheses were not supported by our results. Hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c, H1e, and H1f specifying the areas of ethical marketing practices i.e., product, price, place, person and physical ethics have a positively significant effect on the customer value-brand relationship sustainability. However, H1d was not supported, revealing that promotion ethics has no significant effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability. (γ = 0.047 < p = 0.05). Similarly, H1g also revealed a non-significant effect of packaging ethics on customer value-brand relationship sustainability (γ = 0.094 > p = 0.05). In a similar vein, H2a, H2c, H2d, H2e, H2f and H2g identify that the ethical marketing practices in terms of product, place, promotion, person, physical evidence, and packaging are significantly affecting the value adding product sustainability, whereas H2b shows that price ethics has no significant effect on value adding product sustainability (γ = 0.026 < p = 0.05). Lastly, both H3 identifying the positive relationship between customer value-brand relationship sustainability and brand loyalty and H4 examining the effect of value adding product sustainability on brand loyalty were supported by the results.

The current study studies the role of ethical marketing practices to build positive relationships between customers and brands. Hypotheses testing shows the relationship between these variables and the findings show that, except for promotion ethics and packaging ethics, all other ethical marketing practices have a positive effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability. Similarly, except for price ethics, all other ethical practices have a significantly positive effect on value-adding product sustainability, which is in sync with some prior studies in different geographic and industrial contexts (e.g., [

11,

100,

101,

102]). Our results suggested that product, price, place, person, and physical ethics are very important for customer value-brand relationship sustainability. This shows that products should be free of harm for users and environment. This concept would increase the value to the customer. In the same manner, the ethical place is also equally crucial as a place should not harm any inhabitant in the environment. Moreover, physical and person ethics are essential to customer value-brand relationship sustainability. Nevertheless, ethical price is also essential for the customer, which can be achieved by avoiding any fraudulent or illegal practices in pricing. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the ethical marketing practices regarding product, place, promotion, person, physical evidence, and packaging significantly affect the value-adding product sustainability. Our results reveal that product ethics significantly affect customer value-brand relationship sustainability and value adding product sustainability, suggesting that customers are inclined to purchase the product with the highest level of product safety and quality. Also, the product’s packaging and branding affect customer’s trust and satisfaction, which is why it is important to evaluate the product ethics regarding customer value-brand relationship and sustainability and value-adding product sustainability. Besides, value-adding sustainability is established when the company hones authentic communication under legal legislation and leading abilities, i.e., truthfulness and accurate information about the product, which exhibits trustworthiness in the brand. Packaging ethics has an insignificant effect on customer value-brand relationship sustainability as customers want to see beyond the message the company is sending through their packages. However, packaging ethics have a positive effect on value-adding product sustainability, so it is worthwhile for companies to build up a strong relationship with customers. If a company enhances its relationship quality through product, price, place, promotion, person, physical and packaging ethics, we expect more effectiveness on brand loyalty through exciting relationships with customers.

6.1. Implications

The academic literature on B2C transactions concludes that there is some evidence of positive effects of traditional marketing practices (in the form of product, price, place and promotion) on brand loyalty. However, our contribution to the literature is first of its kind because an improved model for analysis has been used. The focus is on studying the relationship between ethical marketing practices of an extended marketing mix elements and consumer-brand relationship and brand loyalty, which is common in B2C transactions. Our additional theoretical contribution lies in the fact that most of the studies about ethical marketing practices have been conducted in the Western countries, leaving a huge gap in the literature, which this study fills by conducting in a developing economy context of Pakistan. Besides, this study proposes and empirically validates a novel model from a sustainable marketing approach incorporating the role of relationship marketing, which further reflects its theoretical contributions. Lastly, this study further contributes by employing different theories (e.g., ethical marketing theory, relationship marketing theory) to the context of marketing mix elements and brand loyalty, thereby further generalizing the use of these theories.

As for the practical implications are concerned, managers should consider the ethical marketing practices to ensure sustainable success through relationship building and by facilitating long-term brand loyalty. Companies need to focus on improving product parameters like quality, safety, warranties, and eco-friendliness. Companies also need to take price regulations seriously in building sustained loyalty towards the brand. If companies offer a suitable price, they can attract more customers to tighten the relation between them. Customers most probably need the products with more viable prices. If a supplier does not pay heed to the customers with feasible price-concerned morals, the cons of brand truthfulness can be seen at the end. Furthermore, given that promotion-related ethics signifies the vital role in bringing value adding product sustainability. Therefore, firms need to evaluate the promotion related ethics to maximize the trust-based activities to cement the associations with firms. The summarized implication here is that companies/brands can sustain even during the fierce market competition if they establish an ethical culture which gives due preference to trust-based transactions, thereby strengthening customer-firm relationships. Our findings are expected to provide valuable implications to companies so that they support an effective marketing strategy from an ethical perspective.

6.2. Limitations and Suggestions

Regardless of its contribution and implications, this study has several limitations, Firstly, while examining the interplay of marketing ethics and brand loyalty, we didn’t consider B2B transactions. Moreover, our proposed relationships may vary across industrial contexts types, therefore, future studies may further validate our model across study settings. Moreover, future analysis should consider the more ethical practices from the point of government ethics, culture ethics, individual ethics, and religiosity to present further insights of the domain. Some circumstantial and individual factors (e.g., personality type) may act as potential moderators, which future studies can also consider. A longitudinal study may also be conducted to gauge loyalty formation over a period of time.