Sustainable Tourism, Economic Growth and Employment—The Case of the Wine Routes of Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism-Led Growth Hypothesis

2.2. Tourism-Led Employment Hypothesis

3. Study Description

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Endogenous Variables

3.3. Exogenous Variables

3.4. Summary Statistics

4. Results

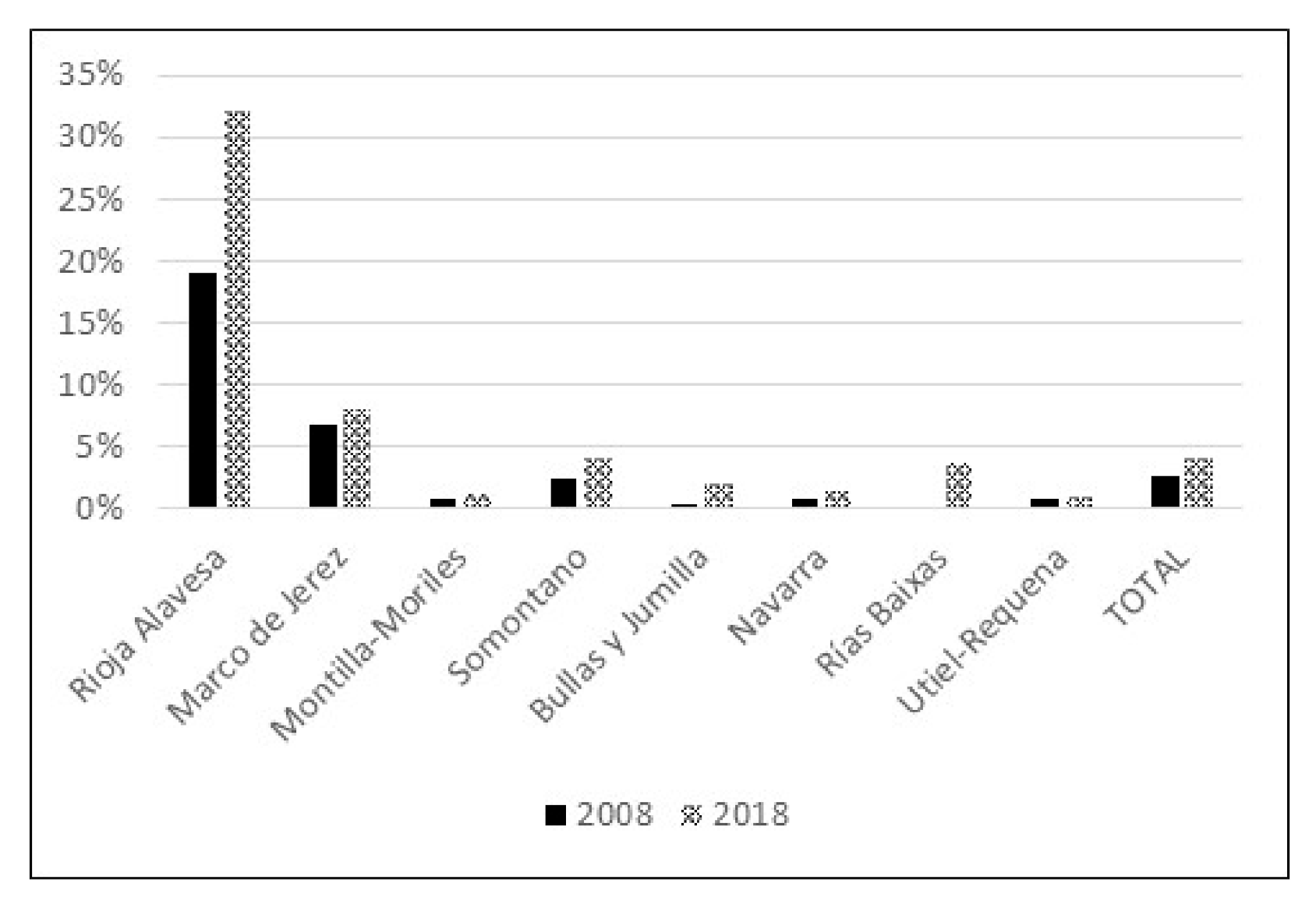

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

4.2. Panel Data Results

4.3. Panel Data Results with Robust Estimators

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Policy and Local Implications and Future Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Getz, D. Explore Wine Tourism, Management, Development and Destinations; Cognizant Communication Corporation: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.; Hall, C.M. Wine tourism research: The state of play. Tour. Rev. Int. 2006, 9, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hede, A.M. Food and wine festivals: Stakeholders. Long-term outcomes and strategies for success. In Food and Wine Festivals and Events around the World: Development, Management and Markets; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 8–101. [Google Scholar]

- Poitras, L.; Getz, D. Sustainable wine tourism: The host community perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casini, L. Sustainability in the wine industry: Key questions and research trends. Agric. Food Econ. 2013, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grimstad, S.; Burgess, J. Environmental sustainability and competitive advantage in a wine tourism micro-cluster. Manag. Res. Rev. 2014, 37, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez-Abad, J.C.; Huertas-García, R.; Vázquez-Gómez, M.D.; Romeo, A.C. Drivers of sustainability strategies in Spain's Wine Tourism Industry. Cornell Hosp. Quaterly 2015, 56, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky, A.; Newton, S.; Atkin, T.; Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casas, A.; Huertas, R. Perceived efficacy of sustainability strategies in the US, Italian, and Spanish wine industries. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2015, 27, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. Georgia Declaration on Wine Tourism. Fostering Sustainable Tourism Development Through Intangible Cultural Heritage; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L.; Cambourne, B.; Macionis, N. (Eds.) Wine Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets; Elsevier: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hojman, D.; Hunter-Jones, P. Wine tourism: Chilean wine regions and routes. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Gomez, M.; Gonzalez-Diaz, B.; Esteban, A. Market segmentation in wine tourism: Strategies for wineries and destinations in Spain. J. Wine Res. 2015, 26, 192–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, B.E.; Rotarou, E.S. Challenges and opportunities for the sustainable development of the wine tourism sector in Chile. J. Wine Res. 2018, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montella, M.M. Wine Tourism and Sustainability: A Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vo Thanh, T.; Kirova, V. Wine tourism experience: A netnography study. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Pratt, M.A.; Molina, A. Wine tourism research: A systematic review of 20 vintages from 1995 to 2014. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2211–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Rodríguez-García, J.; Sánchez-Canizares, S.; José Luján-García, M. The development of wine tourism in Spain. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2011, 23, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Liu, Y. Old wine region, new concept and sustainable development: Winery entrepreneurs´ perceived benefits from wine tourism on Spain´s Canary Islands. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente Ricolfe, J.S.; Escriba-Pérez, C.; Rodríguez-Barrio, J.E.; Buitrago-Vera, J.M. The potential wine tourist market: The case of Valencia (Spain). J. Wine Res. 2012, 23, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Orden, R. The satisfaction of wine tourist: Causes and effects. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 5, 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.; Molina, A. Wine tourism in Spain: Denomination of origin effects on brand equity. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M. Critical factors of wine tourism: Incentives and barriers from the potential tourist´s perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira Rodríguez, A.; López-Guzmán, T.; Rodríguez García, J. Análisis del enoturista en la Denominación de Origen del Jerez-Xérès-Sherry (España). Tour. Manag. Stud. 2013, 9, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez García, J.; del Río Rama, M.d.l.C.; Coca Pérez, J.L.; González Sanmartín, J.M. Turismo enológico y ruta del vino del ribeiro en Galicia-España. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2014, 23, 706–729. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Vieira-Rodríguez, A.; Rodríguez-García, J. Profile and motivations of European tourists on the sherry wine route of Spain. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 11, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Gálvez, J.C.; Muñoz Fernández, G.A.; López-Guzmán Guzmán, T.J. Motivación y satisfacción turística en los festivales del vino: XXXI ed. cata del vino Montilla-Moriles, España. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2015, 11, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruiz, E.; Cruz, E.R.; Zamarreño, G. Rutas enológicas y desarrollo local. Presente y futuro en la provincia de Málaga. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2017, 3, 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Sánchez, A.R.; Ruiz-Chico, J.; Jiménez-García, M.; López-Sánchez, J.A. Tourism and the SDGs: An Analysis of Economic Growth, Decent Employment, and Gender Equality in the European Union (2009-2018). Sustainability 2020, 12, 5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Matesanz Gómez, D.; Segarra, V. On the empirical relationship between tourism and economic growth. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Seetanah, B.; Jaffur, Z.R.K.; Moraghen, P.G.W.; Sannassee, R.V. Tourism and Economic Growth: A Meta-regression Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 404–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcghee, N.G.; Andereck, K.L. Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.C. Community benefit tourism initiatives: A conceptual oxymoron? Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Kang, S.K.; Long, P.; Reisinger, Y. Residents’ perceptions of casino impacts: A comparative study. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, P.; Gursoy, D.; Sharma, B.; Carter, J. Structural modelling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romao, J.; Neuts, B. Territorial capital, smart tourism specialization and sustainable regional development: Experiences from Europe. Habitat Int. 2017, 68, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Martins, A.; Solnet, D.; Baum, T. Sustaining precarity: Critically examining tourism and employment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1008–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchenbach, A.; Hanna, P.; Miller, G. Rethinking decent work: The value of dignity in tourism employment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1026–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torkington, K.; Stanford, D.; Guiver, J. Discourse(s) of growth and sustainability in national tourism policy documents. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1041–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, L. Threshold effect of tourism development on economic growth following a disaster shock: Evidence from the Wenchuan earthquake, PR China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karimi, M.S. The linkage between tourism development and economic growth in Malaysia: A nonlinear approach. Int. Econ. J. 2018, 32, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, G.N.; Sung, W.Y.; Lei, W.G. Regime-switching effect of tourism specialization on economic growth in Asia pacific countries. Economies 2017, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brida, J.G.; Lanzilotta, B.; Pereyra, J.S.; Pizzolon, F. A nonlinear approach to the tourism-led growth hypothesis: The case of the MERCOSUR. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 647–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Stauvermann, P.J. The linear and non-linear relationship between of tourism demand and output per worker: A study of Sri Lanka. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.C.; Liu, S.Y.; Hsiao, J.M.; Huang, T.Y. Nonlinear and time-varying growth-tourism causality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 59, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, S.; Eyuboglu, K. Tourism development and economic growth: An asymmetric panel causality test. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schyff, T.; Meyer, D.; Ferreira, L. An analysis of impact of the tourism sector as a viable response to South Africa’s growth and development challenges. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 12, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, H.; Özer, M. Frequency domain causality analysis of tourism and economic activity in Turkey. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 19, 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, L. Tourism, economic growth, and tourism-induced EKC hypothesis: Evidence from the Mediterranean region. Empir. Econ. 2021, 60, 1507–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, G. Estimating the tourism induced environmental Kuznets curve in France. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramati, S.R.; Alam, M.S.; Chen, C.-F. The effects of tourism on economic growth and CO2 emissions: A comparison between developed and developing economies. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, C.F.; Tan, E.C. Tourism-led growth hypothesis in Malaysia: Evidence based upon regime shift cointegration and time-varying Granger causality techniques. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 1430–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimi, A.; Saint Akadiri, S.; Seraj, M.; Akadiri, A.C. Testing the role of tourism and human capital development in economic growth. A panel causality study of micro states. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.B.; Yeh, L.T. The threshold effects of the tourism-led growth hypothesis: Evidence from a cross-sectional model. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrinjarić, T. Examining the causal relationship between tourism and economic growth: Spillover index approach for selected CEE and SEE countries. Economies 2019, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sokhanvar, A.; Çiftçioğlu, S.; Javid, E. Another look at tourism-economic development nexus. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhowaish, A.K. Is Tourism Development a Sustainable Economic Growth Strategy in the Long Run? Evidence from GCC Countries. Sustainability 2016, 8, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Vita, G.; Kyaw, K.S. Tourism specialization, absorptive capacity, and economic growth. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslija, A.; Satrovic, E.; Erbas, C.Ü. Panel analysis of tourism-economic growth nexus. Uluslararası Ekon. Araştırmalar Derg. 2017, 3, 535–545. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.F.; Tan, E.C. Tourism-led growth hypothesis: A new global evidence. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2018, 59, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risso, W.A. Tourism and economic growth: A worldwide study. Tour. Anal. 2018, 23, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, J.; Cantavella-Jordá, M. Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: The Spanish case. Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- León-Gómez, A.; Ruiz-Palomo, D.; Fernández-Gámez, M.A.; García-Revilla, M.R. Sustainable Tourism Development and Economic Growth: Bibliometric Review and Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Asif, M.; ul Haq, M.Z.; ur Rehman, H. The Contribution of Sustainable Tourism to Economic Growth and Employment in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mathieson, A.; Wall, G. Tourism. Economic, Physical and Social Impacts; Addison Wesley, Longman Limited: Essex, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhove, N. Tourism and Employment. Int. J. Tour. Manag. 1981, 2, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, B.; Fletcher, J. The economic impact of tourism in the Seychelles. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann, J.; Faver, M. Tourism and employment in the Gambia. Ann. Tour. Res. 1984, 11, 249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Burkart, A.J.; Medlik, S. Tourism: Past, Present and Future; Heinemann: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Önder, K.; Durgun, A. Effects of Tourism Sector on the Employment in Turkey: An Econometric Application; Epoka University Press: Tirana, Albania, 2008; pp. 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlić, I.; Tolić, M.S.; Svilokos, T. Impact of tourism on the employment in Croatia. In Recent Advances in Business Management and Marketing: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Management, Marketing, Tourism, Retail, Finance and Computer Applications; Raguz, I.V., Roushdy, M., Salem, A.-B.M., Eds.; WSEAS Press: Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2013; pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Condratov, I. The Relation between Tourism and Unemployment: A Panel Data Approach. J. Tour. Stud. Res. Tour. 2017, 23, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, J.; Vogt, C.A. Indentifying the role of cognitive, affective, and behavioural components in understanding residents’ attitudes toward place marketing. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.P.; Chancellor, H.C.; Cole, S.T. Measuring residents’ attitudes toward sustainable tourism: A reexamination of the sustainable tourism attitude scale. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Sirakaya, E. Measuring residents’ attitudes Howard sustainable tourism: Development of a sustainable tourism attitude scale. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronza, A.; Gordillo, J. Community views of ecotourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 448–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T.; Bosley, H.E.; Dronberger, M.G. Comparisons of stakeholder perceptions of tourism impacts in rural eastern North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. Tourist-resident impact: Examples and emerging solutions. In Global Tourism: The Next Decade; Theobald, W.F., Ed.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, K.; Sirakaya, E.E.; Ingram, L.J. Testing the efficacy of an integrative model for community participation. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akis, S.; Persistianis, N.; Warner, J. Residents’ attitudes to tourism development: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Puczkó, L.; Rátz, T. Tourist and resident perceptions of the physical impacts of tourism at Lake Balaton, Hungary: Issue for sustainable tourism management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 458–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.; Bressan, A. Small rural family wineries as contributors to social capital and socioeconomic development. Community Dev. 2013, 44, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, B.; Gartner, W.; Appiah, G. Economic Contribution of Vineyards and Wineries of the North; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, A. Wineries’ contribution to the local community: A stakeholder view. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Res. 2017, 12, 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, B.; Gartner, W. Vineyards and Wineries in the New England States. A Status and Economic Contribution Report; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Route | Province (NUTS 3) | Region (NUTS 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Bullas | Murcia | Murcia |

| Jumilla | Murcia | Murcia |

| Marco de Jerez | Cádiz | Andalucía |

| Montilla-Moriles | Córdoba | Andalucía |

| Navarra | Navarra | Navarra |

| Rías Baixas | Pontevedra | Galicia |

| Rioja Alavesa | Álava | Basque Country |

| Somontano | Huesca | Aragón |

| Utiel-Requena | Valencia | Valencian Community |

| Route | Wine Tourists (Units) (1) | Wineries (Units) (2) | (1)/(2) | Province | GDPpc (US Dollar) | Unemployment Rate (%) | Tourists (Thousands) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | ||

| Bullas | 11,339 | 65,145 | 15 | 18 | 755.93 | 3619.17 | Murcia | 20,327.17 | 21,170.87 | 15.29 | 15.83 | 2804.61 | 3205.74 |

| Jumilla | |||||||||||||

| Marco de Jerez | 434,161 | 582,351 | 33 | 31 | 13,156.39 | 18,785.52 | Cádiz | 18,008.31 | 17,605.75 | 21.80 | 27.35 | 6321.88 | 7187.73 |

| Montilla-Moriles | 12,343 | 24,513 | 16 | 16 | 771.44 | 1532.06 | Córdoba | 17,414.63 | 18,420.38 | 20.19 | 22.47 | 1505.59 | 1932.17 |

| Navarra | 12,368 | 25,605 | 16 | 10 | 773.00 | 2560.50 | Navarra | 29,770.71 | 31,169.69 | 8.13 | 9.99 | 1349.10 | 1916.10 |

| Rías Baixas | 7011 | 116,557 | 28 | 60 | 250.39 | 1942.62 | Pontevedra | 21,258.50 | 22,187.65 | 11.96 | 14.38 | 2975.01 | 3205.88 |

| Rioja Alavesa | 80,688 | 192,213 | 40 | 58 | 2017.20 | 3314.02 | Álava | 37,407.22 | 37,828.61 | 7.79 | 7.39 | 421.61 | 599.45 |

| Somontano | 46,099 | 79,601 | 16 | 16 | 2881.19 | 4975.06 | Huesca | 27,004.34 | 29,755.06 | 6.64 | 9.94 | 1847.58 | 1951.92 |

| Utiel-Requena | 47,496 | 76,627 | 24 | 10 | 1979.00 | 7662.70 | Valencia | 22,993.16 | 23,336.98 | 13.70 | 13.17 | 6400.25 | 7665.08 |

| Total | 651,505 | 1,162,612 | 188 | 219 | 2823.06 * | 5548.95 * | Spain | 24,129.26 | 25,726.91 | 11.25 | 15.26 | 23,625.62 ** | 27,664.06 ** |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GDPpc | 10.014 | 0.256 | 9.639 | 10.540 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | Unemp | 2.919 | 0.444 | 1.893 | 3.745 | −0.857 | 1 | |||

| 3 | wines | 3.110 | 0.541 | 2.302 | 4.094 | 0.110 | 0.062 | 1 | ||

| 4 | w_tour | 10.894 | 1.115 | 8.855 | 13.274 | 0.003 | 0.157 | 0.627 | 1 | |

| 5 | tour | 14.627 | 0.781 | 12.933 | 15.852 | −0.680 | 0.501 | −0.217 | 0.214 | 1 |

| po1 | re1 | fe1 | po2 | re2 | fe2 | po3 | re3 | fe3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tour | −0.2233 *** | 0.2108 *** | 0.2908 *** | −0.2344 *** | 0.2113 *** | 0.2984 *** | −0.2710 *** | 0.2340 *** | 0.3275 *** |

| w_tour | 0.0361 | 0.0051 | −0.0043 | 0.0852 *** | 0.0005 | −0.0114 | |||

| wines | −0.1432 ** | 0.0225 | 0.0442 | ||||||

| _cons | 13.2816 *** | 6.9306 *** | 5.7612 *** | 13.0504 *** | 6.8678 *** | 5.6953 *** | 13.4962 *** | 6.5156 *** | 5.2116 *** |

| N | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| r2 (1) | 0.4624 | 0.4114 (1) | 0.4114 (1) | 0.4858 | 0.4053 (1) | 0.4124 (1) | 0.5291 | 0.4198 (1) | 0.4270 (1) |

| Breusch-Pagan test: | |||||||||

| chibar2 | 319.39 | 324.24 | 314.60 | ||||||

| Prob > chibar2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| F test u_i = 0 | F(7,79) = 255.86 | F(7,78) = 241.58 | F(7,77) = 223.26 | ||||||

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| Hausman test: | |||||||||

| chi2 | −38.70 | −64.88 | −70.93 | ||||||

| Prob > chi2 | ------ | ------ | ------ | ||||||

| po1 | re1 | fe1 | po2 | re2 | fe2 | po3 | re3 | fe3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tour | 0.2847 *** | −0.1206 | −1.0219 *** | 0.2783 *** | −0.2012 | −1.2464 *** | 0.3382 *** | −0.1897 | −1.2978 *** |

| w_tour | 0.0208 | 0.0201 | 0.1247 * | −0.0596 | −0.0026 | 0.1373 * | |||

| wines | 0.2343 * | 0.1577 | −0.0784 | ||||||

| _cons | −1.2445 | 4.6830 * | 17.8672 *** | −1.3776 | 5.6445 ** | 19.7940 *** | −2.1071 * | 5.2319 * | 20.6516 *** |

| N | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| r2 (1) | 0.2511 | 0.2206(1) | 0.2206 (1) | 0.2537 | 0.2608 (1) | 0.2608 (1) | 0.2925 | 0.1463 (1) | 0.2628 (1) |

| Breusch-Pagan test: | |||||||||

| chibar2 | 111.08 | 109.34 | 104.05 | ||||||

| Prob > chibar2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| F test u_i = 0 | F(7,79) = 25.22 | F(7,78) = 26.72 | F(7,77) = 24.53 | ||||||

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| Hausman test: | |||||||||

| chi2 | 29.87 | 33.45 | 31.26 | ||||||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||

| Growth | Unemployment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| re1 | re2 | re3 | fe1 | fe2 | fe3 | |

| tour | 0.2108 ** | 0.2113 * | 0.2340 * | −1.0219 * | −1.2464 * | −1.2979 * |

| w_tour | 0.0051 | 0.0005 | 0.1246 ** | 0.1373 * | ||

| wines | 0.0225 | −0.0784 | ||||

| _cons | 6.9306 *** | 6.8677 *** | 6.5156 *** | 17.8671 ** | 19.7939 ** | 20.6516 ** |

| N | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| r2 | 0.4114 | 0.4053 | 0.4198 | 0.2207 | 0.2608 | 0.2628 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vázquez Vicente, G.; Martín Barroso, V.; Blanco Jiménez, F.J. Sustainable Tourism, Economic Growth and Employment—The Case of the Wine Routes of Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137164

Vázquez Vicente G, Martín Barroso V, Blanco Jiménez FJ. Sustainable Tourism, Economic Growth and Employment—The Case of the Wine Routes of Spain. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137164

Chicago/Turabian StyleVázquez Vicente, Guillermo, Victor Martín Barroso, and Francisco José Blanco Jiménez. 2021. "Sustainable Tourism, Economic Growth and Employment—The Case of the Wine Routes of Spain" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137164

APA StyleVázquez Vicente, G., Martín Barroso, V., & Blanco Jiménez, F. J. (2021). Sustainable Tourism, Economic Growth and Employment—The Case of the Wine Routes of Spain. Sustainability, 13(13), 7164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137164