The Effects of European Recommendations on the Validation of Lifelong Learning: A Quality Assurance Model for VET in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Laws, norms, regulations, etc.

- Policies

- Description of the validation system, organization, institutional affiliation, etc.

- The involved agents, organizations, labour market, etc.

- The skills of the validation professionals, certification, potential competence requirements and opportunities for the development of competences

- Methods for validation

- Identification of common tools for the development of VET

- Development of the systems according to the needs of the people

- Redefinition of open and various learning environments through VET frameworks, which allow mobility and validation between different levels and educational contexts

- Implementation of quality assurance systems in VET in collaboration with all stakeholders

2. Theoretical Framework

- Individual rights

- Obligations of the responsible

- Reliability and confidence

- Credibility and legitimacy

- Making reality learning throughout life and mobility

- Improving the quality and efficiency of education and training

- Promoting equity, social cohesion and active citizenship

- Consolidating creativity and innovation, including the entrepreneur skill, considering education and training levels

- Individual rights. The process should be voluntary and egalitarian for access and evaluation, becoming the person at the centre of the procedure.

- Obligations of the responsible. Processes with the guarantee of quality should be established, which provide information as well as counselling to people about their rights, procedure, phases and outcomes. The transfer must also be ensured and provide access to formal VET systems.

- Reliability and confidence. Quality should ensure that the process is fair and transparent, considering reliable instruments and the professionalism of the consultants and evaluators.

- Credibility and legitimacy. These should be based on quality tools that ensure the participation of all those interested in the procedure as well as the recognition and the validity of the results.

- Flexibility and quality.

- Adaptation to the labour market and emerging needs.

- Boosting learning throughout life.

- Ensuring the sustainability and the excellence of the Education and Professional Training (EFP) through a common approach to quality control.

- Promoting the acquisition of essential competences.

- Innovation for the development of products and services.

- Mobility of young people, enhancing the performance of the education system, promoting non-formal and informal learning as well as the labour incorporation.

- Digital agenda for Europe; unique digital market access to the entire population.

- Effective use of resources with sustainable management in all areas.

- Industrial policy, competitiveness, globalization and social responsibility.

- Agenda for new qualifications and jobs, which improves employment, and training of workers and students.

- European platform against poverty, increasing cooperation between the member states.

- UNESCO established directives for the recognition, validation and accreditation of different types of learning [35].

- The European Council’s proposal for a Council Recommendation on the validation of non-formal and informal learning [36] where the factors indicated in the Europe 2020 Planning were defined, as well as the socio-economic crisis and young people unemployment.

- The identification of a person’s particular experience through dialogue.

- The documentation that enables to make visible the experience of the person.

- A formal evaluation of that experience.

- The recognition of full or partial qualification, which leads to a certification.

- The person is the centre of the validation system; this process is voluntary and the privacy of the person must be protected and respected. Moreover, an equitable and fair treatment must also be ensured.

- Information related to validation should be made available to the citizen. It will be provided in a coordinated manner and it will identify the different responsibilities between the agencies involved.

- Validation must be procedural and covers four main stages: identification, documentation, evaluation and certification of non-formal and informal learning.

- The validation process must be documented to facilitate transparency and recognition, using existing European and national tools.

- Guidance and advice are essential for people to be able to adapt validation to their needs and interests.

- The validation must be part of the vocational training systems. People should have the ability to obtain a degree, based on the validation of their learning outcomes.

- The validation criteria are defined and described through the learning outcomes formulated as knowledge, skills and competences. These will use the same standards as those defined to regulate formal learning.

- The quality assurance must be an explicit and integrated part of the validation processes, being reliable and transparent. Quality must also be at all stages of the validation process in a manner that ensures the reliability and duration of the entire process, from the identification of information to recognition.

- The training of professionals involved in the process must be ensured.

- Common European Principles for the determination and validation of non-formal and informal education (Council of the EU 9600/04 EDUC 118 SOC 253, 18 May 2004).

- European Guidelines for the validation of non-formal and informal learning of Cedefop in 2009 [33].

- Council Recommendation on the validation of non-formal and informal learning [36].

- The proposal of the new Cedefop Guidelines that were published in 2015 [26].

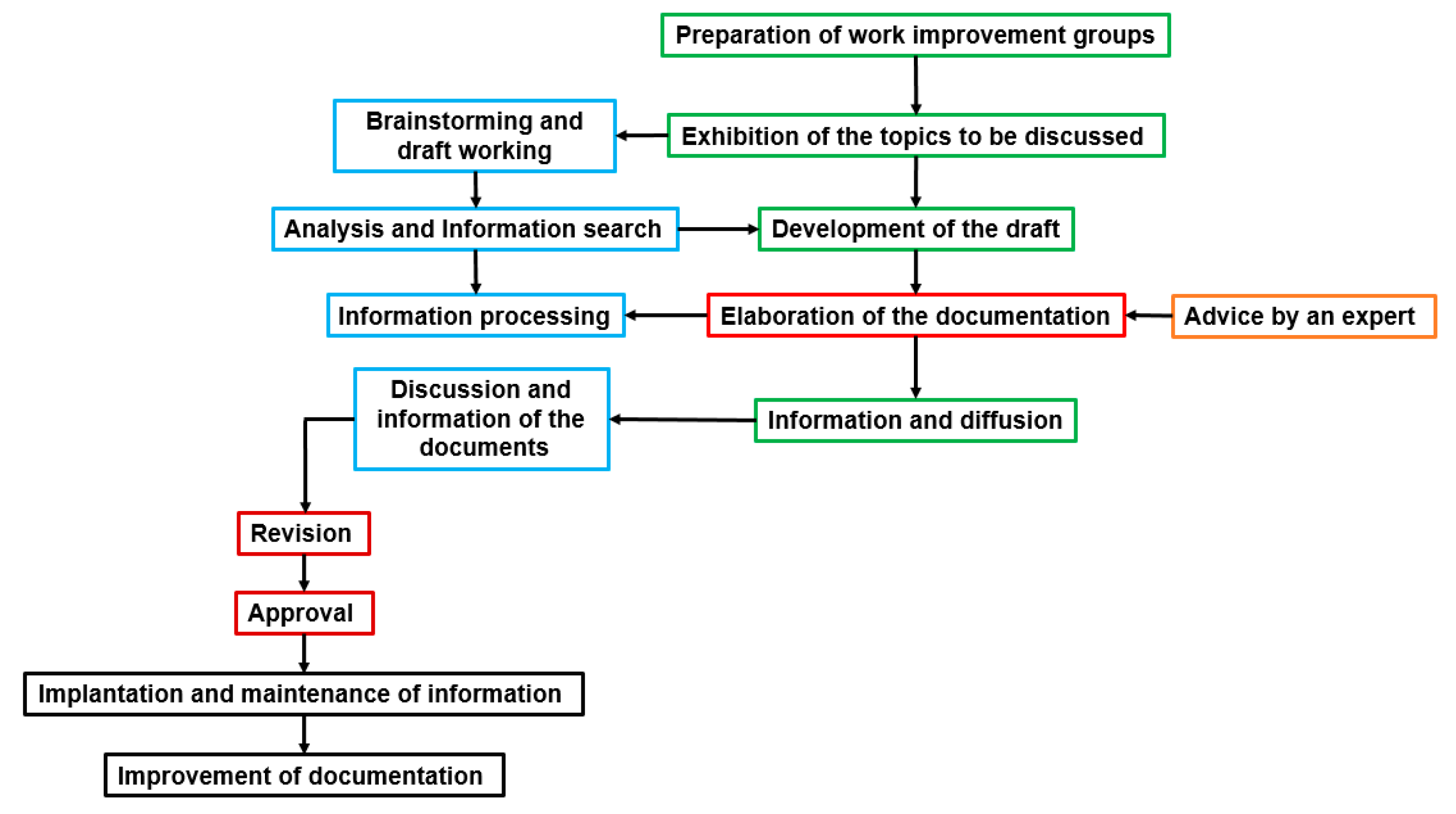

3. Methodology

- Diagnosis of the validation procedure status in Europe and Spain

- Documentary analysis of the regulations for the procedure development in the Autonomous Communities

- Analysis of the calls carried out in the Autonomous Communities

- Diagnosis of positions offered for the accreditation and the qualifications convened as well as the public resources used

- Preparation of Instruments/Forms for diagnosis

- Field of work: obtaining the required information

- Analysis of the information collected

- Preparation of a report about the accreditation procedure in Spain

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the Validation Principles in European Recommendations

4.2. Analysis of the Validation Principles in National Regulations

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Terokhina, N. Recognition of the Results of Non-Formal Adult Education: American Experience. Sci. Educ. 2017, 25, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. The Benefits of Vocational Education and Training; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Keeton, M.T. Experiential Learning; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J. Prior Learning Assessment: Does Dewey’s Theory Offer Insight? Prior Learning Assessment: Does Dewey’s Theory Offer Insight? New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2018, 158, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, L. A Review of Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) Literature in Quebec. Can. J. Study Adult Educ. 2017, 30, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Aarkrog, V.; Wahlgren, B. Assessment of Prior Learning in Adult Vocational Education and Training. Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paulos, C. Qualification of Adult Educators in Europe: Insights from the Portuguese Case. Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guimarães, P. Reflections on the Professionalisation of Adult Educators in the Framework of Public Policies in Portugal. Eur. J. Educ. 2009, 44, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienzo, P.D. Recognition and Validation of Non Formal and Informal Learning: Lifelong Learning and University in the Italian Context. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 2014, 20, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, M.; van den Berg, G. The Significance of the Learner Profile in Recognition of Prior Learning. Adult Educ. Q. 2018, 68, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werquin, P. The Missing Link to Connect Education and Employment: Recognition of Non-Formal and Informal Learning Outcomes. J. Educ. Work 2012, 25, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisan Weber, S.; Voit, J.; Lengauer, S.; Proinger, E.; Duvekot, R.; Aagaard, K. Cooperate to Validate: OBSERVAL-NET Experts’ Report on Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning (VNFIL); Research Report; European University Continuing Education Network (EUCEN), 2014. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED559370 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. European Inventory on Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning: 2016 Update; Synthesis Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Bermúdez, N. European Inventory on Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning 2014: Country Report Spain; ICF International: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training; European Commission; ICF. European Inventory on Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning 2018 Update; Synthesis Report; European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training; European Commission; Villalba-Garcia, E.; Endrodi, G.; Murphy, I.; Scott, D.; Souto-Otero, M. European Inventory on Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning: 2018 Update: Executive Summmary; Final Synthesis Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dahler, A.M.; Grunnet, H. Quality in Validation in the Nordic Countries. Final Report for “Quality in the Nordic Countries—A Mapping Project”; National Knowledge Centre for Validation of Prior Learning: Aarhus, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kleef, J.V. Kvalitet I vurdering og anerkendelse af realkompetencer. In Anerkendelse af Realkompetencer—En Antologi; Aagaard, K., Enggaard, E., Grunnet, H., Larsen, J., Dahler, A.M., Duvekot, R., Helms, N.H., Høyrup, S., Larsen, N., Nordentoft, A., et al., Eds.; VIA Systime: Åarhus, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Declaration of the European Ministers of Vocational Education and Training, and the European Commission, convened in Copenhagen on 29 and 30 November 2002, on enhanced European cooperation in vocational education and training—‘The Copenhagen Declaration’. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM:ef0018 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- European Commission. Maastricht Communiqué on the Future Priorities of Enhanced European Cooperation in Vocational Education and Training (VET) (Review of the Copenhagen Declaration of 30 November 2002). Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/education/news/ip/docs/maastricht_com_en.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- European Commission. Draft Conclusions of the Council and of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States Meeting within the Council on Common European Principles for the Identification and Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning (9175/04 EDUC 101 SOC 220); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Presidency Conclusions Barcelona European Council 15 and 16 March 2002. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/PRES_02_930 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Real Decreto 1224/2009, de 17 de Julio, de Reconocimiento de Las Competencias Profesionales Adquiridas Por Experiencia Laboral. BOE 2009, 205, 72704–72727.

- Carro, L. Country Report Spain. 2016 Update to the European Inventory on Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning; ICF International: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. Cedefop European Public Opinion Survey on Vocational Education and Training; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. European Guidelines for Validating Non-Formal and Informal Learning; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnavold, J. Making Learning Visible: Identification, Assessment and Recognition of Non-Formal Learning in Europe; Publications Office of the EU: Luxembourg, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. White Paper on Education and Training. Teaching and Learning. Towards the Learning Society; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the Recognition of Professional Qualifications. Off. J. Eur. Union L 2005, 255, 22. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Bordeaux Communiqué on Enhanced European Cooperation in Vocational Education and Training. Communiqué of the European Ministers of Vocational Education and Training, the European Social Partners and the European Commission Convened in Bordeaux on November 26 2008 to Review the Priorities and Strategies of the Copenhagen Process; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. European Training Thesaurus; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2008; Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/3049_en.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- European Commission. EUROPE 2020 A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. European Guidelines for Validating Non-formal and Informal Learning; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Bruges Communiqué on enhanced European Cooperation in Vocational Education and Training for the period 2011–2020. Communiqué of the European Ministers for Vocational Education and Training, the European Social Partners and the European Commission, Meeting in Bruges on 7 December 2010 to Review the Strategic Approach and Priorities of the Copenhagen Process for 2011–2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/bruges_en.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- UNESCO. UNESCO Guidelines for the Recognition, Validation and Accreditation of the Outcomes of Non-Formal and Informal Learning; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning: Hamburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Council Recommendation of 20 December 2012 on the Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning. Off. J. Eur. Union C 2010, 398, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnavold, J. Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning in Europe. The Challenging Move from Policy to Practice; Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Serreri, P. El Balance de Competencias y la Orientación Profesional: Teoría y Práctica. Reflexiones en Torno al Balance de Competencias: Concepto y Herramientas para la Construcción del Proyecto Profesional. In Reflexiones en Torno al Balance de Competencias: Concepto y Herramientas para la Construcción del Proyecto Profesional; Figuera Gazo, P., Rodríguez Moreno, M.L., Eds.; Publicacions i Edicions Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; pp. 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2009 on the Establishment of a European Credit System for Vocational Education and Training (ECVET). Off. J. Eur. Union C 2009, 155, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Misko, J. Regulating and Quality Assuring VET: International Developments; National Centre for Vocational Education Research: Adelaide, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kreysing, M. Vocational Education in the United States: Reforms and Results. Vocat. Train. Eur. J. 2001, 23, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pilz, M. Training Patterns of German Companies in India, China, Japan and the USA: What Really Works? Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pilz, M.; Li, J. Tracing Teutonic Footprints in VET around the World? The Skills Development Strategies of German Companies in the USA, China and India. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 38, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, N.; Schwartz, R. Gold Standard: The Swiss Vocational Education and Training System. International Comparative Study of Vocational Education Systems; National Center on Education and the Economy: Geneve, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pilz, M. Typologies in Comparative Vocational Education: Existing Models and a New Approach. Vocat. Learn. 2016, 9, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrini Acuña, M. Como se Elabora el Proyecto de Investigación: (Para los Estudios Formulativos o Exploratorios, Descriptivos, Diagnósticos, Evaluativos, Formulación de Hipótesis Causales, Experimentales y los Proyectos Factibles); Consultores Asociados BL: Caracas, Venezuela, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, M.S.; Seco, M.P. La Excelencia Operativa en la Administración Pública: Creando Valor Público: Guía Para la Implantación de la Gestión Basada en Procesos en la Administración Pública; Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, D. Fundamentos de Estadística; Bisquerra Alzina, R., Ed.; La Muralla: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía Navarrete, J. Sobre La Investigación Cualitativa. Nuevos Conceptos y Campos de Desarrollo. Investig. Soc. 2014, 8, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J. Bases de la Investigación Cualitativa: Técnicas y Procedimientos para Desarrollar la Teoría Fundamentada; Universidad de Antioquía: Medellín, Colombia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vilà, R.; Bisquerra Alzina, R. El análisis cuantitativo de los datos. In Metodología de la Investigación Educativa; Bisquerra Alzina, R., Ed.; La Muralla: Madrid, Spain, 2004; pp. 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Manual de Investigación Cualitativa; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Argibay, J.C. Muestra en Investigación Cuantitativa. Subj. Procesos Cogn. 2009, 13, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gan Bustos, F.; Triginé Prats, J. Análisis y Problemas en la Toma de Decisiones; Editorial Díaz de Santos: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ley Orgánica 5/2002, de 19 de Junio, de Las Cualificaciones y de La Formación Profesional. Boletín Of. del Estado 2002, 147, 20.

- Chisvert-Tarazona, M.J.; Ros-Garrido, A.; Abiétar-López, M.; Carro, L. Context of Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning in Spain: A Comprehensive View. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2019, 38, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. Overview of National Qualifications Framework Developments in Europe 2020; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Kerres, M.; Bedenlier, S.; Bond, M.; Buntins, K. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Staboulis, M.; Sytziouki, S. Constructivist Policy Rational for Aligning Non-Formal and Informal Learning to Mechanism for Validation and Recognition of Skills: The Case of Cyprus. J. Educ. Soc. Policy 2021, 8, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Ehlers, S. Recognition of Prior Learning. Andrag. Spoznanja 2019, 25, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Document | Context | Principles | Recommendations | Phases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common European Principles 18/05/2004 |

|

|

|

|

| European Directives 04/11/2009 |

|

|

|

|

| Recommendations- Validations 20/12/2012 |

|

|

|

|

| New European Directives 2015 |

|

|

|

|

| Principles 2004 | Directives 2009 | Directives UNESCO 2009 | Recommendations 2013 | Directives Project 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Rights | Individual rights | Voluntariness, privacy and access in equality and equity. | Validation as an Essential complement of LLL | The person is the centre of the validation process. | |

| Credibility and Legitimacy | Credibility and legitimacy | Impartiality and Regulation of the evaluation results. | Alignment with other tools such as Europass, ECTS, ECVET | The qualification criteria are defined and described through the learning outcomes as knowledge, skills and competences. | |

| Reliability and Confidence | Reliability and confidence | Quality assurance systems | Quality systems will be used to ensure the reliability, validity and credibility of the process. | Quality assurance must be an explicit and integrated part of the validation process. | |

| Obligations of the Responsible | Obligations of the responsible | Guidance and advising | Training of the responsible of the validation process. Economic sustainability of the validation systems. | Sustainable cost | The professional competencies of the validation counsellors and evaluators should be developed. |

| Information | Accessibility of the validation systems. | Information procedures will be defined, about the process and their outcomes | Information about validation should be made available, close the place where citizens live. | ||

| Identification of the Phases | Elements that allow to determine, to document and to evaluate as well as to certify learning outcomes, equal to those of formal education. | Validation has different purposes and four main stages. | |||

| Orientation and Advice | Guidance and advising procedures will be defined on the process and their results. | Guidance and advising are essential for people to be able to adapt validation to their needs. | |||

| Integration in National Frame | Validation as part of the VET systems. | Sustainable integration in a national qualifications framework. | Validation should be part of systems and national qualifications frameworks. | ||

| Employability | Validation must fortify the employability of people. | ||||

| Documentation of the Process | The validation documentation. | ||||

| Participation and Coordination | Participation | Coordination and integration of stakeholders. | To promote the participation, collaboration and coordination of the different stakeholders, companies and the VET supplier centres. | GI coordination from the definition of the legal framework, the organization and procedure management as well as the detection of needs. |

| Principles and elements of the validation of the learnings. Research technique: Comparative analysis. Study parameters: Principles and validation elements. Study units: Recommendations and Guidelines on Validations according to the EU. | |

| Categories | Variables |

| Principles | Individual rights |

| Credibility and legitimacy | |

| Reliability and confidence | |

| Obligations of those responsible | |

| Elements | Information |

| Identification of the phases | |

| Guidance and advice | |

| Employability | |

| Documentation of the process | |

| Participation and coordination | |

| Principles and elements of the validation of the learnings. Research technique: Documental analysis. Study parameters: Principles and validation elements. Study units: Competency accreditation regulations in Spain. | ||

| Categories | Variables | Attributes |

| Regulation | Date | Year |

| Type of Regulation | Normative | |

| Announcement | ||

| Competent organ | Educative administration | |

| Labour administration | ||

| Both | ||

| Others | ||

| Regulatory status | Decree | |

| Order | ||

| Resolution | ||

| Others | ||

| Framework | European | Permanent learning |

| Validation of learning | ||

| Mobility | ||

| Employability | ||

| Competitiveness | ||

| Flexibility of itineraries | ||

| EQAVET Framework | ||

| Spanish | Personal development throughout life | |

| Attention needs productive system | ||

| Participation and cooperation agents involved | ||

| Adaptation of EU criteria | ||

| Validation Principles | Person centre of the process | |

| Next information | ||

| Adapted orientation | ||

| Independent stages | ||

| Integration National frameworks | ||

| Competences recognition | ||

| Training of human resources | ||

| Obligations of those responsible | ||

| Processes documentation | ||

| Validation Principles 2004 | Guidelines Cedefop 2009 | Guidelines UNESCO 2012 | Recomme- Dations 2012 | Guidelines Projet 2015 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principles | Individual rights | X | X | X | X | 4 | 80% | |

| Credibility and legitimacy | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | 100% | |

| Reliability and confidence | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | 100% | |

| Obligations of those responsible | X | X | X | X | 4 | 80% | ||

| Elements | lnformation | X | X | X | 3 | 60% | ||

| ldentification of the phases | X | X | 2 | 40% | ||||

| Guidance and advice | X | X | X | 3 | 60% | |||

| lntegrati on national frameworks | X | X | X | 3 | 60% | |||

| Employability | X | 1 | 20% | |||||

| Documentation of the process | X | 1 | 20% | |||||

| Participation and coordination | X | X | X | X | 4 | 80% | ||

| 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 11 | ||||

| 36% | 45% | 64% | 73% | 100% |

| REGULATION | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | Type | Competent organ | Rank | |||||||||||||

| National Regulations | 2002 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 1012 | 2013 | Normative | Announcwemente | EVT education | EVT employ | Both | Others | Law | Deree | Order | Resolution |

| Law 5/2002 (Consolidated) | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Royal Decree 1224/2009 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| ORDER PRE 910/2011 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| ORDER PRE 3480/2011 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| FRAMEWORKS | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUROPEAN | SPANISH | |||||||||||||

| National Regulations | Permanent learning | Validation of learning | Mobility | Employability | Competitiveness | Flexibility of itineraries | EQAVET Framework | Personal development | Attention needs productive | Participation and cooperation | Adaptation of EU criteria | TOTAL | PERCENTAGE | |

| Law 5/2002 (Consolidated) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 | 73% | ||||

| Royal Decree 1224/2009 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | 64% | |||||

| Order PRE 910/2011 | X | 1 | 9% | |||||||||||

| Order PRE 3480/2011 | X | X | 3 | 60% | ||||||||||

| TOTAL | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | |||

| PERCENTAGE | 50% | 75% | 50% | 50% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 50% | 50% | 100% | 25% | |||

| PRINCIPLES OF VALIDATION | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Regulations | Person centre of the process | Next information | Adapted orientation | Independent stages | National frameworks | Competence recognition | Training advisors / evaluators | Processes documentation | TOTAL | PERCENTAGE |

| Law 5/2002 (Consolidated) | X | X | X | X | X | 8 | 73% | |||

| Royal Decree 1224/2009 | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | 64% | |||

| Order PRE 910/2011 | X | X | 1 | 9% | ||||||

| Order PRE 3480/2011 | X | X | X | X | 3 | 60% | ||||

| TOTAL | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |||

| PERCENTAGE | 0% | 100% | 50% | 0% | 100% | 75% | 75% | 0% | ||

| STRATEGY | RESOURCES AND SYSTEMS | ||||||||||||||||||||

| To improve the detection of needs and expectations | To increase the transparency | To increase knowledge of the procedure | Adaptation to European Frameworks | To increase the participation of interest groups | Adequacy of accreditation offer | National accreditation map | To adapt the norm to the needs | To improve the Education-Employment link | Increased flexibility of the EVT System | Development of a permanent and open procedure | Network of centres for the accreditation | Use of EVT teacher network | To improve the coordination systems | To improve public-private collaboration | Web tools for self-management of the procedure | To improve the procedure monitoring | To improve the training and qualification of experts | To define a system of fees and exemptions | To improve the procedural sustainability | ||

| STRATEGY | To improve the detection of needs and expectations | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| To increase the transparency | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| To increase knowledge of the procedure | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Adaptation to European Frameworks | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| To increase the participation of interest groups | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Adequacy of accreditation offer | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| National accreditation map | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| To adapt the norm to the needs | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| To improve the Education-Employment link | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Increased flexibility of the EVT System | |||||||||||||||||||||

| RESOURCES AND SYSTEMS | Development of a permanent and open procedure | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Network of centres for the accreditation | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Use of EVT teacher network | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| To improve the coordination systems | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| To improve public-private collaboration | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Web tools for self-management of the procedure | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| To improve the procedure monitoring | |||||||||||||||||||||

| To improve the training and qualification of experts | |||||||||||||||||||||

| To define a system of fees and exemptions | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| To improve the procedural sustainability | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ACREDITATION PROCESS | RESULTS | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universality and adaptability | To approach the information and the guidance | To implement the balance of competencies | To improve the cost benefit of the procedure | To improve agility in recognition | To increase the reliability and validity of procedure | Designs of formative itineraries | Use of the procedure phases independently | To improve evaluation tools | To increase the efficiency and the effectiveness | To increase the employability and the mobility | To increase the qualification throughout life | To improve the impact of the procedure | To increase the utility procedure | To improve the competitiveness of the companies | ||

| RESOURCES AND SYSTEMS | Development of a permanent and open procedure | |||||||||||||||

| Network of centres for accreditation | ||||||||||||||||

| Use of EVT teacher network | ||||||||||||||||

| To improve coordination systems | ||||||||||||||||

| To improve the public-private collaboration | ||||||||||||||||

| Web tools for self-management of the procedure | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| To improve the procedure monitoring | ||||||||||||||||

| To improve the training and qualification of experts | X | |||||||||||||||

| To define a system of fees and exemptions | X | |||||||||||||||

| To improve procedural sustainability | ||||||||||||||||

| ACREDITATION PROCESS | Universality and adaptability | |||||||||||||||

| To approach the information and guidance | ||||||||||||||||

| To implement the balance of competencies | X | |||||||||||||||

| To improve the cost benefit of the procedure | ||||||||||||||||

| To improve the agility in the recognition | ||||||||||||||||

| To increase the reliability and the validity of procedure | X | |||||||||||||||

| Designs of formative itineraries | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Use of the procedure phases independently | X | |||||||||||||||

| To improve evaluation tools | X | |||||||||||||||

| To increase the efficiency and the effectiveness | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| RESULTS | To increase the employability and the mobility | |||||||||||||||

| To increase the qualification throughout life | X | |||||||||||||||

| To improve the impact of the procedure | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| To increase the utility procedure | X | |||||||||||||||

| To improve the competitiveness of the companies | ||||||||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Redondo, A.; Castillo, S.; Carro, L.; Martín, P. The Effects of European Recommendations on the Validation of Lifelong Learning: A Quality Assurance Model for VET in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7283. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137283

Redondo A, Castillo S, Carro L, Martín P. The Effects of European Recommendations on the Validation of Lifelong Learning: A Quality Assurance Model for VET in Spain. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7283. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137283

Chicago/Turabian StyleRedondo, Alfonso, Salvador Castillo, Luis Carro, and Paulino Martín. 2021. "The Effects of European Recommendations on the Validation of Lifelong Learning: A Quality Assurance Model for VET in Spain" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7283. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137283