1. Introduction

Participatory approaches to monitoring are growing in many parts of the world; an upsurge in community-based monitoring and citizen science initiatives is evident in many contexts, jurisdictions, and in response to varied questions of ecological sustainability [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. This decentralization of monitoring has largely been hailed as a positive trend in environmental governance and an opportunity to grow knowledge and capacity for improved resource management [

13]. Monitoring in large watersheds presents particularly unique opportunities for learning and improved decision-making, however, the large scale and complexity of these social–ecological systems also present major challenges [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Where monitoring is driven by local and Indigenous communities with long histories and strong relationships to place and the lakes and rivers being monitored, the prospects for improving watershed sustainability are significant, with the greatest insights coming from those with “boots on the ground” or “boats in the water” [

19].

Previous research has highlighted the failures that can come with not listening to local experts; this is particularly well-evidenced in cases where fishers’ knowledge has not been recognized. Examples include the collapse of the North Atlantic cod stocks and the decline of the white sturgeon in the Lower Fraser Basin [

20,

21]. While much of the research on fishers’ knowledge has been carried out in marine ecosystems [

22,

23], there is also need for greater monitoring in freshwater ecosystems [

24,

25,

26]. The Mackenzie River Basin in northwestern Canada is among the river systems considered data-poor and at risk [

27,

28]. Data gaps not only relate to biophysical elements and processes (e.g., changes in water flow, impacts of climate on fish health); there is also little documented about this watershed as a social–ecological system. Given the vital contribution of the Mackenzie and other large watersheds to the livelihoods of local and Indigenous peoples, as well as escalating pressures of climate change and resource development on freshwater resources, addressing these gaps has never been more urgent.

We argue that indicators and methods of monitoring based on Indigenous knowledge have the potential to contribute to our understanding of large watersheds; however, a top-down and one-size-fits-all approach is not useful in large river basins like the Mackenzie. Research in other large, complex, and dynamic ecosystems suggests a more participatory approach to monitoring that builds on the varied knowledge, practices, and beliefs of local and Indigenous peoples, yields more meaningful outcomes, and avoids scale mismatches between knowledge producers and users [

29]. In the context of large watersheds, creating opportunities for communities to voice their observations and experiences of environmental change can go a long way to addressing the lack of fit that currently exists between the local “scale of meaning” (where ecological problems are acutely experienced) and those associated with formal institutions of decision-making [

30,

31]. Given that the knowledge of local and Indigenous fishers is characterized as more holistic in its framing of human–environmental change, participatory approaches to monitoring can yield deeper and richer understandings of watersheds as social–ecological systems [

32,

33]. Engaging multiple stakeholders and knowledges in large ecological systems, like the Mackenzie, has often flummoxed decision makers who tend to prefer a simplified, “one-size-fits-all” approach. However, a monitoring approach that embraces multiple methods, tools, and rules for monitoring may indeed produce outcomes that are more reflective of the fine-scale social–ecological changes that have meaning to local peoples. Such an approach can also produce a rich tapestry of insights and meanings at the watershed scale.

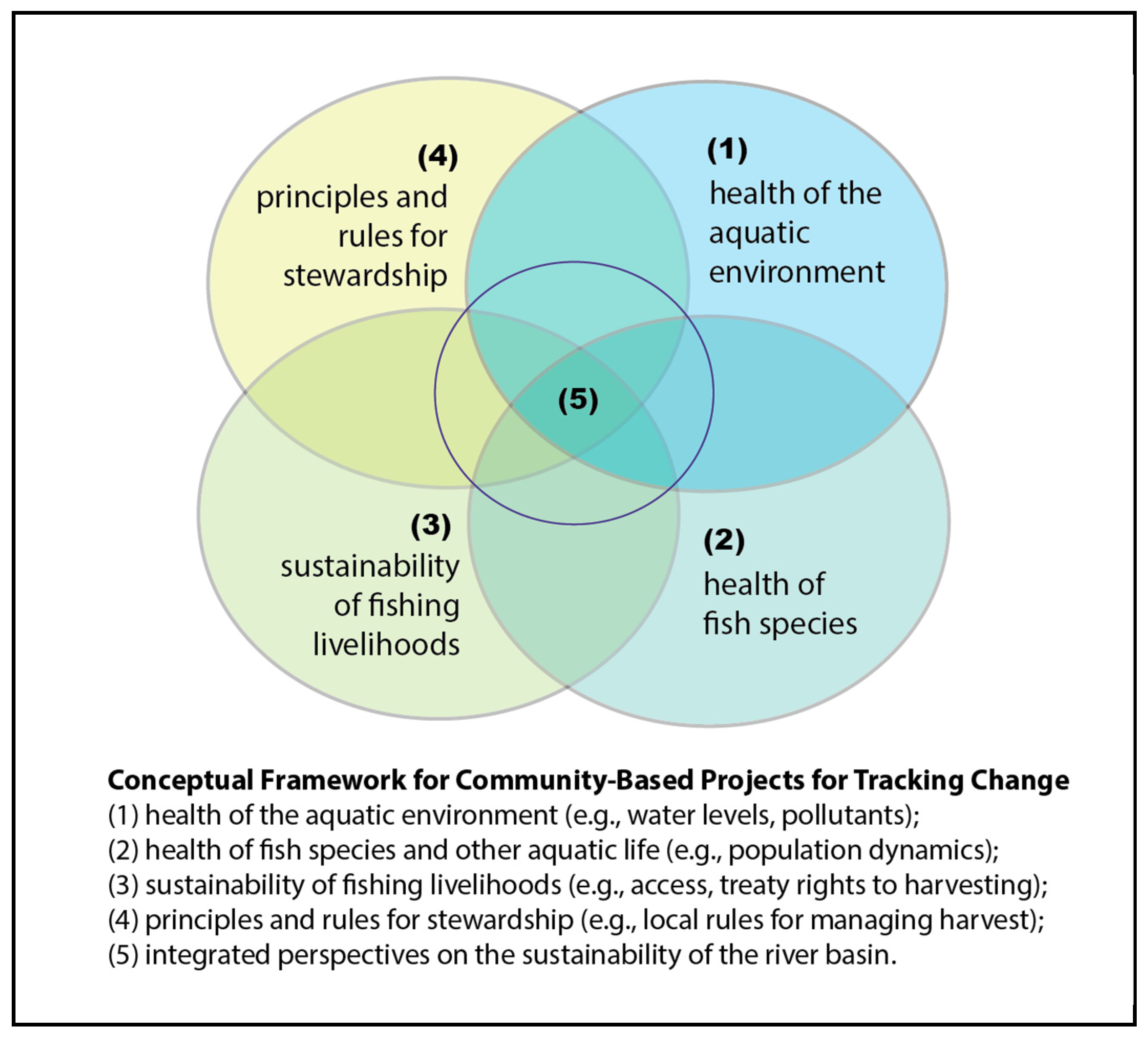

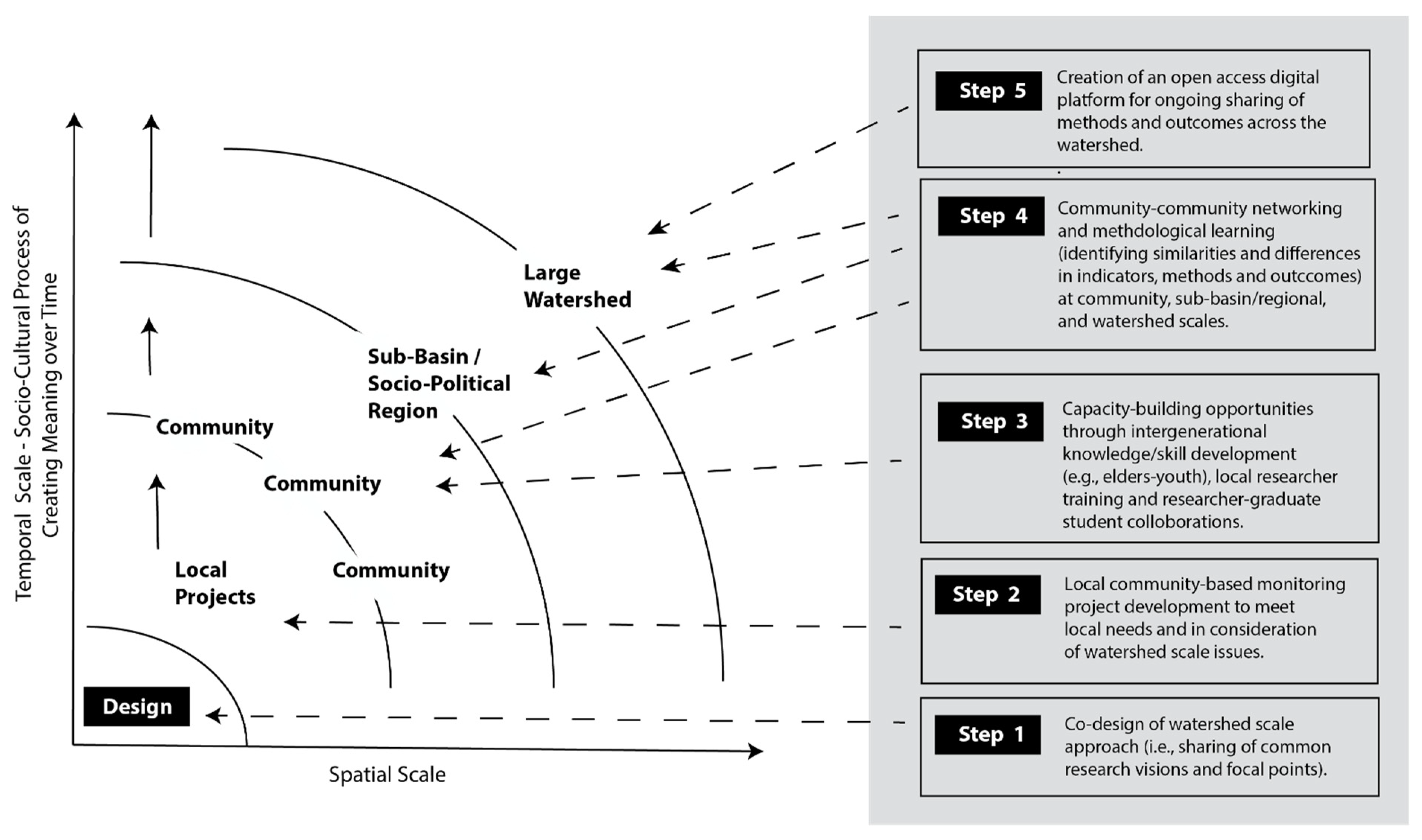

This paper reflects on this problem of scale by presenting a model of “methodological

bricolage” for community-based monitoring in large watersheds. The model, inspired by methodological inquiry in various fields [

34,

35,

36], articulates how a variety of methods, tools, and rules-in-use for monitoring, although seemingly disjointed, can effectively work together to produce insights about social and ecological changes that are useful from local to basin-wide scales. The model is informed by four years of collaborative research between Indigenous governments and organizations in the Mackenzie River Basin (2015–2018). The paper summarizes the indicators and monitoring methods developed by 12 Indigenous governments and organizations and reflects on the combined outcomes of this work and that carried out through sister projects in two other major watersheds (Amazon, Mekong). We suggest these outcomes may be complementary to conventional science approaches; we then argue that a networked approach to community-based monitoring that embraces Indigenous knowledge, practices, and beliefs offers major opportunities for addressing gaps in knowledge about large watersheds as social–ecological systems in ways that can improve sustainability for future generations. We further suggest that the project work in the Mackenzie River Basin offers lessons applicable to other systems and locations where connecting local and regional information and experiences is both necessary and challenging.

2. The Need for Methodological Bricolage in the Monitoring of Large Watersheds

The term

bricolage in research emerged in various streams of anthropology and sociology as a reference to the very grounded and concrete approach to building knowledge from “what is available” and the value of multiplicity of cultural knowledges, norms, and practices in studying a particular phenomenon and in strengthening institutions [

35,

37,

38,

39]. This framework has since developed in other fields, including ecology and geography, with the aim of addressing questions of fit between different research tools, the capacities, and knowledge needs of local peoples engaged in the research process [

9,

40,

41,

42,

43].

Methodological

bricolage is more than a mixed or multi-method research approach in that it considers the social and political complexity of meaning-making and the reflective and relational aspect of the inquiry process [

36]. It emerges within a post-positivist social science paradigm, which rejects the idea of objectivity and recognizes that “ecological change” is not a data point, but a construct shaped by diverse histories and social–cultural processes [

43]. As in other forms of sociological inquiry, “

bricoleurs” are also concerned with intersections of power in how research is carried out, how knowledge is created and recognized (or not) in decision-making. It has also been used as a lens for analyzing Indigenous livelihoods and the ways in which land users, “improvise, hybridize, contest, and negotiate existing practices to create different kinds of adaptive arrangements” [

9], p. 437. We advance this work on methodological

bricolage by considering how such a framework is useful in monitoring and when dealing with scalar problems. More specifically, we see a particular role for a methodological

bricolage in the practice and evolution of community-based monitoring as a networked approach to learning in large watersheds.

Inter-program planning and implementation of community-based monitoring create opportunities to think about how different monitoring activities in different places are interconnected [

44]. However, much more attention in monitoring design has been paid to questions of theme and tactic, with lesser consideration of scalar questions of synthesis and meaning. Balancing the necessity of tracking finer-scale changes that have meaning and significance to local and Indigenous peoples while at the same time building knowledge about larger-scale ecological phenomena is important. It is among the greatest challenges facing those living in and governing large watersheds, and more challenging still, given that ecological and social change are interrelated [

32,

33]. Changes occurring within the aquatic system can have different meanings and significance depending on the perspective of the individual or social group. What is meaningful to one community may seem insignificant to another. In addition, shifts in biophysical conditions can have reverberating impacts on the social, economic, and cultural well-being of individuals and communities dependent on basin resources [

32]. Few monitoring programs have considered the interrelated nature of ecological and social change [

33,

45,

46,

47] and considered the opportunities that can come from bringing together diverse methods and knowledge systems, including those developed by Indigenous peoples [

32,

48].

2.1. Indigenous Knowledge in Monitoring

Indigenous approaches to monitoring can be found in diverse ecosystems and cultures globally. A diversity of indicators, approaches, and methods based on Indigenous knowledge has been documented over the last two decades [

14,

15,

18,

33,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. While only a recent topic of interest for academics, many Indigenous monitoring systems are hundreds if not thousands of years old, and indicators are often deeply rooted in oral histories and livelihood practices. For example, elders in Łútsël K’e Dene First Nation know that the backfat of caribou is an important indicator of the reproductive success of caribou herds [

55]. Monitoring (or “watching, listening, learning and understanding change”) [

56] is not something that stands apart from the day-to-day lives of community members but rather is embedded within the way of life of the community and socio-cultural practices such as hunting, trapping, fishing, harvesting of plants, and cultural and spiritual ceremony [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65].

At a glimpse, Indigenous-led monitoring programs may appear little different from those based on science, in that they rely on systematic and rigorous empirical observation. For example, Dene use of length–weight ratios in fish and catch-per-unit-effort metrics to assess fish health are similar to those used by many Indigenous peoples [

49]. However, there are key differences [

63,

64,

65]. Indeed, they may be viewed as complementary to and synergistic with existing approaches to monitoring based on Western science. As such, the opportunities for knowledge co-production through monitoring (e.g., use of Indigenous knowledge and Western science) are significant.

Despite similarities, Indigenous knowledge systems are rooted in unique ontologies that challenge Western science dichotomies around the physical and spiritual worlds. For example, in some northern Dene cultures, monitoring is not about what we do to nature (i.e., measuring change) but about what nature does and says to us. As articulated by Inuit and First Nations in northern and western Canada, trees, plants, rocks, animals, and fish all “have stories to tell” [

65] about changes in the natural world [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70].

Indigenous approaches to monitoring, which are built on strong cultural and spiritual relationships to place, can result in unique observations and insights not accounted for by others. As noted by the late Denesọłine elder, Morris Lockhart, “those who don’t care would not notice the changes” [

49]. These insights come from long-term relationships to, and living (dwelling) in, place [

71]. Those with a strong sense of place can often easily distinguish between patterns of natural ecological variability and changes that are considered outside the scope of natural variability [

72,

73,

74].

Values of care, stewardship, and responsibility (i.e., a moral imperative) can also translate into different kinds of approaches to monitoring. For example, Dene and Inuit harvesters in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut track animal movements at critical habitat locations (e.g., water crossings sites, mountain passes, and other landscape features) [

75,

76,

77]. This is perceived as more respectful than more invasive methods such as tagging and collaring of animals (e.g., polar bear, caribou) [

67,

74,

78].

Clear incentives for doing monitoring “the right way” are foundational to many Indigenous monitoring practices. Hunters, fishers, and other land users engage in monitoring to ensure their safety and health. For example, failure to measure ice thickness (e.g., using observations such as distribution of leads, cracks, and pressure ridges) would result in injury or loss of life for Inuit, as reported in Sachs Harbour [

79]. Over the long term and in many places around the globe, these Indigenous-led monitoring systems have been proven to be imperative to social–ecological learning, yielding important biodiversity outcomes (e.g., conservation, avoidance of species collapse) [

55,

57,

72,

80,

81] as well as critical social and health outcomes (i.e., food security, resilience to hazards, and well-being) [

6,

82,

83].

The continued sustainability of Indigenous livelihoods, and the species and ecosystems on which they depend, is evidence of the success of such monitoring efforts and associated management systems. Case study examples relate to barren-ground caribou, pacific salmon, beluga whale, and polar bear as well as boreal biodiversity [

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89]. At global scales, the story is even more compelling; while Indigenous peoples comprise just 5% of the global population and occupy, own, or manage an estimated 20 to 25% of the Earth’s land surface, this land area holds 80% of the planet’s biodiversity [

90,

91], speaking both to the stewardship achieved by Indigenous peoples and to the need for their involvement in continuing to monitor and conserve social–ecological systems.

2.2. Participation and Power in Monitoring

Community-based monitoring initiatives in Canada and globally have increased significantly in recent decades [

19,

92]. This shift toward more decentralization is occurring amidst a backdrop of public concern over the environment and a variety of resource management failures (e.g., the collapse of North Atlantic cod stocks) caused in part by errors in conventional science and top-down institutions [

93,

94,

95,

96,

97]. Greater engagement of the public in the work of tracking changes in the health of the environment is also made more feasible by technological innovation of affordable communication and scientific technologies [

13,

15,

98].

Efforts to increase local engagement and community participation in monitoring are often predicated on the assumption that “increasing citizens’ voice will make public institutions more responsive to citizens’ needs and demands and therefore more accountable for their actions” [

99] (p. ix). The nature and degree of participation vary. While some monitoring programs are led wholly by outside academics, governments, or others (in which Indigenous peoples make minor contributions) [

2,

3], others are led wholly by Indigenous organizations and are based on Indigenous knowledge.

Indigenous leadership in monitoring and, more generally, in natural resource management is expanding with recognitions of Indigenous rights (e.g., through the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples). In Canada, demands for the decolonization of state institutions have also contributed to the rediscovery and development of various monitoring programs (e.g., Indigenous Guardians) [

92,

100]. But for many leaders and participants, being a Guardian is as much about sovereignty as it is about the technical process of data collection. Their work in effect is a form of collective action and reconciliation through which they can confront and address systemic inequities in the production and use of knowledge about values, lands, and resources [

101,

102,

103]. For this reason, community-based monitoring approaches, often characterized as bottom-up, holistic, and hands-on, stand as a compelling alternative to conventional kinds of scientific monitoring, which are often top-down, disciplinary, and technocratic [

72,

101]. However, there are many barriers to the success of formally recognized monitoring programs (e.g., limited long-term funding and capacity). As such, there are important questions to be asked about whether community-based monitoring programs represent a real sharing of power. For example, how does the lack of long-term funding and program certainty for Indigenous monitoring programs affect process and outcomes? Can knowledge co-production be achieved within the requirement to perform monitoring according to the bureaucratic and administrative parameters of external agencies, or do those parameters constitute an insurmountable barrier to self-determination?

Despite being celebrated in many circles, community-based monitoring programs are sometimes criticized as too simplistic or localized to offer insights into large-scale and complex ecological problems [

104,

105]. There are also criticisms that advocates have a romanticized idea of “community” and homogenized local perspectives, and they ignore ethnic, socioeconomic, cultural, and gender diversity [

106,

107,

108,

109]. Moreover, many scientists and governments have been quick to dismiss the indicators, methods, and outcomes of community-based monitoring on the basis that Indigenous peoples are non-experts, not objective, and tend to complicate or undermine the legitimacy of scientific work by not following standardized and conventional protocols [

110,

111,

112]. The assumption, however, that scientific protocols and research (that stem from European traditions of science) are value-free and more systematic and rigorous than Indigenous approaches is highly colonialist and short-sighted in orientation [

108,

113]. Overcoming these barriers to, and assumptions about, community-based monitoring involves challenging established institutions and beliefs about what constitutes expertise. It also involves a recognition that scale is not something fixed and objectively defined, but is socially constructed, fluid, and embedded in relationships between people and place [

104,

105].

We enter into the debate about scale, subjectivity, and the legitimacy of Indigenous indicators and methods by describing a networked approach to community-based monitoring aimed at understanding social–ecological change in the Mackenzie River Basin. The indicators and methodological approaches designed and used by Indigenous governments and organizations in their own projects reflect a high degree of social and ecological specificity to place. Nurturing this specificity and diversity of approaches is a strength, rather than a weakness, of the research and its outcomes; in other words, “one-size does not fit all”. It is this diversity that is the key strength of the approach. Although there was a deliberate lack of top-down direction toward the standardization, there is nonetheless a commonness to the methods developed in each of the regions and, as a result, opportunities to braid outcomes together to improve learning and decision-making at both local and basin-wide scales.

The paper provides a summary of the results of community-based monitoring programs from the Basin. By sharing examples from 12 monitoring initiatives led by Indigenous governments (2015–2018), we offer (1) insights from individual programs, and whether they are limited to the local scale or if they provide a diverse understanding of change across the entire Basin when knitted together; (2) characteristics of Indigenous monitoring, and how approaches and methods can be adapted from one area to another; and (3) examples of the benefits of such programs, including their potential to contribute to decolonization. The findings have policy implications. We suggest that a networked approach to community-based monitoring can be useful both to decision makers in national and regional governments and to local leaders. The approach may help us embrace the complexity and diversity of Indigenous knowledge, practices, and beliefs to build interdisciplinarity at different geographic and temporal scales across a river basin or an ecosystem.

4. Results

In this section, we present summaries of 12 monitoring case studies conducted in the Mackenzie Basin under the auspices of Tracking Change. We describe each one in turn to reflect the distinct contributions made by the individuals and communities involved, following a consistent format to allow for comparisons among them. In the next section, we present a synthesis across the case studies, intended to illustrate broadly applicable lessons for community-based monitoring carried out at the river basin or ecosystem scale.

4.1. Inuvialuit Joint Secretariat—Fisheries Joint Management Committee

The Inuvialuit are the most northerly Indigenous peoples in the Mackenzie River Basin, with livelihoods dependent on the resources of the Mackenzie Delta and the Beaufort Sea. More than 10 species of fish from the delta and local tributaries are harvested seasonally and are among a diversity of marine and freshwater species that contribute to local food security. An estimated 3300 Inuvialuit people live in six communities in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, two of which are located in the Mackenzie Delta (Aklavik and Inuvik). The Inuvialuit Final Agreement of 1984 recognized Inuvialuit rights for hunting, trapping, and fishing in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region and created institutions of community-based, co-managed resources including fisheries [

121,

141]. One of these organizations, the Fisheries Joint Management Committee (FJMC) was the main partner in this project, with local management institutions in Aklavik and Inuvik (Aklavik Hunters and Trappers Committee and Inuvik Hunters and Trappers Committee) leading specific projects from 2016–2018. A long history of research work in this region led by the Inuvialuit Joint Secretariat provided the foundation for this work carried out with Aklavik and Inuvik fishers. As previously mentioned, numbered areas correspond to locations highlighted in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12.

4.2. Gwich’in Renewable Resources Board

The Gwich’in of the Northwest Territories live within the Mackenzie Delta with traditional territories that stretch along the main stem of the Mackenzie River as well as the Peel River and its tributaries in the Mackenzie and Richardson Mountain ranges. Their territory is defined as the Gwich’in Settlement Region and was created through the settlement of a Comprehensive Land Claim with the federal government in 1992. The total population of the Gwich’in Settlement Area, including Gwich’in beneficiaries, Inuvialuit, Métis, and non-Indigenous peoples, is approximately 5100. The Gwich’in Tribal Council, Gwich’in Renewable Resources Board, and associated community-level management councils in each of Fort McPherson, Tsiigehtchic, Aklavik, and Inuvik are directly involved in fisheries management in this area. Fish are an important resource and constitute a large part of the Gwich’in subsistence economy. Over 20 years of research about the Mackenzie Delta and the Peel River, led by the Gwich’in Social and Cultural Institute, and the Gwich’in Renewable Resources Boards, formed the foundation for this work carried out between 2015–2018.

Table 2.

Gwich’in Renewable Resources Board—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

2]).

Table 2.

Gwich’in Renewable Resources Board—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

2]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| The Gwich’in held 10 fish camps, semi-directed interviews, and fishing activities in 2016–2018 involving more than 60 fishers, elders, and youth. | - ○

age/condition, abundance; - ○

migration patterns of valued fish species; - ○

total fish harvest; contribution to subsistence; - ○

water levels, flow, and water quality; - ○

aquatic habitat conditions.

| - ○

fish camps; - ○

training of youth (use of GPS digital cameras, audio recorders); - ○

elder–youth knowledge sharing; - ○

skill development of youth (setting nets and jigging for fish, making dry-fish) to for experiential learning by youth; - ○

semi-structured interviews with elders/fishers; - ○

fishers were employed to class and take measurements of 5–10 fish per day for 2 days/week over 10 weeks including species, length–weight ratio, age, and qualitative condition (377 fish total).

|

| Example of Findings: There is growing concern that the contribution of fish to the diet is in decline because of limited fishing skills among younger generations, attributed in part to the impacts of residential school, increased access to store-bought foods, lack of socioeconomic resources for harvesting (e.g., a limited number of boats and nets), and safety concerns about traveling on the lakes and rivers (Proverbs et al. 2020). Fishers have also observed changes in species migration and distribution in the last 10 years (i.e., fish runs are less predictable now) as well as changes in species including observations of salmon and char. “They aren’t as sure of when they will be catching certain species.” Another key finding includes best practices for assessing fish populations in both the Peel and Mackenzie Rivers based on Gwich’in harvester tracking of catch-per-unit-effort data. |

4.3. Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation

The Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation is a Northern Tutchone community located in Mayo, Yukon. The community has just over 400 people; the majority of its settlement areas are located in the Stewart River but the First Nation also has traditional use areas in the Peel River watershed in the Nash Creek area. The First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun was involved in establishing the Bonnet Plume Canadian Heritage River and producing the management plan for this river. The culture and economy of Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation are interconnected with the natural resources of the Yukon including the Mackenzie Basin. Previous research carried out by the Nation in the Stewart River watershed (adjacent to the Peel) contributed to the success of the work carried out between 2015–2018.

Table 3.

Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

3]).

Table 3.

Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

3]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| A youth camp was held in 2016 to develop skills for travel on the land/water as well as increased capacity for ecological observations. A structured survey of active fishers that had been previously designed and implemented since 2009 was conducted, with results summarized by band staff. | fish health (size, cysts, parasites); fish population migration patterns; fish habitat; water levels; water quality.

| semi-structured interviews with elders/fishers; youth training and experiential learning travel on the land into the Peel River watershed; harvest and traditional knowledge surveys about the health of fisheries of the Peel River and the Stewart River.

|

| Example of Findings—Drawing on the survey data about fish population, migration, and condition, Nacho Nyak Dun fishers highlighted critical concerns about changes in the abundance of species, warming water temperatures, increased observations of parasites and lesions on harvested fish of all species, and increasing water levels and associated decrease in access to key fishing sites. There was more variability in ice conditions. Freeze-up and break-up conditions are changing with freeze-up of the local lake being about three weeks later in the last several years than previously. Warmer water conditions seem to be leading fish to deeper water (becoming less accessible in some lakes) and/or resulting in harvested fish being mushier than is considered normal. |

4.4. Ɂehdzo Got’ıneGots’éNákedı—Sahtú Renewable Resources Board

The Sahtú people live in four communities (Colville Lake, Délınę, Fort Good Hope, Norman Wells, and Tulita) on the main stem of the Mackenzie and on Great Bear Lake. In 1993, the Sahtú Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement was signed, affirming their fishing rights (and hunting, trapping). As in the Gwich’in and Inuvialuit regions, community-based and co-management institutions were created to formalize stewardship practices in the region. Among these is the Ɂehdzo Got’ıneGots’éNákedı (Sahtú Renewable Resources Board). Fishing on Great Bear Lake, local tributaries, (e.g., Great Bear River) as well as on the Mackenzie River itself is a common practice and contributes significantly to the food security of people in the region. A long history of research work in this region led by the Sahtú Renewable Resources Board and other organizations in Délınę provided the foundation for this work carried out in 2015–2018.

Table 4.

Sahtú Renewable Resources Board—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

4]).

Table 4.

Sahtú Renewable Resources Board—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

4]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| On Great Bear Lake and the Mackenzie River, four fish camps were coordinated, involving elders, fishers, and youth, 50+ semi-directed interviews, and fishing activities in 2016–2018. | age/condition, abundance, migration patterns of fish; total contribution of fish harvest to subsistence; water levels, quality, habitat conditions; climate—risks of travel on the lake/rivers, changes in water access, harvest contributions to food security, safety.

| fish camps; training of youth; skill development of youth (setting nets, making dry-fish); semi-structured interviews with elders/fishers/youth; elder–youth knowledge sharing.

|

| Example of Findings: Respondents shared a wealth of knowledge about fishing practices and their harvesting travels, past and present. People are still very actively harvesting fish in the region, particularly lake trout, whitefish, and herring, which has always been and continues to be important to the diet of the Sahtú people, particularly of Délınę; eating and fishing practices vary by season and by families in the community and the region. Observations of abnormal conditions, patterns, and events, including lower water levels, warming water temperatures, erratic weather events (resulting in thinning ice), as well as changes in the patterns and timing of fish movements and migration (e.g., cisco), contributes to improved understanding of the impacts of climate change in the region and the associated impacts on fishing livelihoods. |

4.5. Dehcho First Nations

The Dehcho First Nations is a tribal council representing the Dene (South Slavey) and Métis people of the Dehcho Region of the Northwest Territories, Canada. It is made up of 10 First Nations Bands and two Métis groups. Multiple sub-basins of the Mackenzie flow through the Dehcho region, including the waters of the Great Slave, the Liard, and the Mackenzie Great Bear. Łíídlıı Kų́ę́ First Nation of Fort Simpson is one of the largest Dehcho communities with more than 760 members. As with other Dene in the Basin, their economy, culture, and diet are intertwined with the river and its resources. Significant research in the region led by the Dehcho First Nations provided the foundation for this work, which contributed to a larger initiative led by the Nation—the Dehcho K’éhodi Stewardship Program.

Table 5.

Dehcho First Nations—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

5]).

Table 5.

Dehcho First Nations—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

5]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| Canoe trip from Fort Simpson to Willow Lake River and interviews with Łíídlıı Kų́ę́ First Nation (Fort Simpson) elders and fishers to document changes in the river. An additional study of risk perception of water quality with Kátł’odeecheFirst Nation (2017–2018) | age/condition, abundance, migration patterns, valued fish species; total contribution of fish harvest to subsistence; invasive species; water levels, quality, habitat conditions; climate—risks of travel on the lake/rivers, changes in water access, harvest contributions to food security, safety.

| observation/recording of changes on the river; training of youth—skill development (navigation, paddling, setting nets); youth empowerment (sense of self, place, and identity); semi-structured interviews with individuals/ households; elder–youth knowledge sharing.

|

| Example of Findings—Water levels are decreasing in the Dehcho and water is becoming siltier with increasing landslides and permafrost thaw. Many of the respondents were also aware of reports of increasing mercury concentrations within the food chain, particularly in some kinds of fish. Despite these changes, most respondents indicated that there was nowhere in the region (likely outside of the Mackenzie River itself) where they felt they could not drink the water. Respondents also tended to describe at least one and sometimes multiple places where they thought the water was especially pure and high quality. |

4.6. Łútsël K’é Dene First Nation

Łútsël K’é, or “Place of the cisco fish”, is located on the east arm of Great Slave Lake; the population of 350 Denesọłiné (Chipewyan Dene) is accessible only by air, boat, or snowmobile. The harvesting of fish from Great Slave Lake and other areas has always been a vital aspect of local livelihoods for the Denesọłiné. Community members have always harvested fish during summer months when barren-ground caribou populations returned to their spring and summer calving grounds far from the community. Today, fishing remains an important source of subsistence. Approximately 75–100 people from the community are active set-net fishers. Harvests are shared or traded within the community; everyone consumes fish daily or weekly in the summer months and periodically during winter months. Setting nets during both the summer and winter months is an important skill valued by the community and one being passed on to younger generations. The work carried out (2015–2018) built upon a long history of research led by the Nation, including that under a local monitoring program Ni Hat Ni, “watching the land”.

Table 6.

Łútsël K’é Dene First Nation—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

6]).

Table 6.

Łútsël K’é Dene First Nation—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

6]).

| Activities | Key Indicator | Monitoring Method |

|---|

Canoe trip from Ɂehdacho Kúé (Artillery Lake) to Desnethch’e (Fort Reliance) and interviews with Łútsël K’e elders and fishers. First Nation workshops with elders and fishers to document changes in the river; this work was part of the Ni Hat Ni monitoring program in the region, which is focused primarily in the Lockhart River sub-basin.

Fall fish camps were also held at Wildbread Bay in 2018, on the east arm of Great Slave Lake to assess fish health. | place names; total contribution of fish harvest to subsistence; water levels, quality, habitat conditions; climate—risks of travel on the lake/rivers, changes in water access, harvest contributions to food security, safety; age/condition, diversity, abundance, migration patterns.

| experiential learning by youth; observation/recording of changes on the river and local lakes; semi-directed interviews with elders (carried out by youth); participatory mapping; workshops to document and share observations.

|

| Example of Findings—There are more than 100 active fishers in the community of Łútsël K’e. Fishers began noticing a decrease in water levels in the early 2000s. According to some, the water has dropped five feet (i.e., the shoreline has extended five feet). As noted by one land user, “The [water level of the] whole lake has gone down. About five feet, I’d say. And that’s probably been within the last ten to fourteen years, something like that. I noticed, we started getting longer summers.” Semi-structured interviews have also highlighted areas in Great Slave Lake, the Lockhart River, and Nonacho Lake regions where fishers have observed changes in the health of fish stocks and conditions, which residents attribute to mining activity and hydroelectric development. There are observations in some areas of Great Slave Lake of skinnier fish; fish with big heads and skinny bodies are of particular concern in the east arm of Great Slave Lake as observed by some fishers of Łútsël K’e Dene First Nation: “The fish are different, skinny fish, the way they are growing is not the same, big head small tail, crooked fish, not straight, that’s what [we’ve] seen.” |

4.7. Akaitcho Territory Government

Akaitcho Dene First Nation members reside primarily in the southeastern part of the Northwest Territories in four communities around Great Slave Lake: Dettah, N’dilo, Deninu K’ue, and Łútsël K’e. Akaitcho translates as “Big Foot” and refers to a historically important Dene leader. Akaitcho is credited with bringing his people into the fur trade and with establishing a peace treaty with the neighboring TłıchoDene. The Akaitcho Territory Government represents the collective environmental, social, political, cultural, and economic interests of its member First Nations. These communities with long histories of subsistence fishing surround Great Slave Lake. Research led by this organization built upon many years of research and monitoring work in the region.

Table 7.

Akaitcho Territory Government—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

7]).

Table 7.

Akaitcho Territory Government—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

7]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| A workshop was held on the land with elders, youth, and chiefs from all the Akaitcho communities attending. | | experiential learning and skill development by youth; elder–youth knowledge sharing; sharing of oral histories and place names; documenting and sharing of observations while traveling on the water.

|

| Example of Findings—Elders note that the travel routes through the lake area are changing due to lower water levels. Historically, people knew the safe routes to take, but now they are in danger with lower water, reefs, and bigger islands. Youth are starting to use more technology to map the reefs and make newer safer travel routes that stick to deeper water levels. Although things are changing, some principles and rules for living on the land are still the same, such as “the weather is the boss”. During the workshop elders taught the youth how to check when bad weather is coming based on the color of the water. Youth expressed interest in traveling to new and other areas of Akaitcho territory to learn how to travel and learn about the stories from those places. |

4.8. Dena Kayeh Institute

The Dena Kayeh Institute (DKI), located in Lower Post, British Columbia, is a non-profit society established in 2004 and created to empower, preserve, and protect the Kaska Dena language, oral traditions, history, culture, and traditional knowledge. DKI has a mandate that focuses on the safeguarding of traditional knowledge and interests in land protection. This mandate connects to the Kaska Dena’s vision to reclaim our role as stewards of the land and resources within our ancestral territory. DKI is a community-run and led organization contributing to and supporting land and resource management within the Kaska Traditional Territory while advocating for Kaska Dena laws, culture, and traditions. A long history of mining in the area, coupled with the impacts of climate change, has led to ecological, socioeconomic, and cultural stress in this sub-basin (Liard sub-basin).

Table 8.

Dena Kayeh Institute—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

8]).

Table 8.

Dena Kayeh Institute—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

8]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| The project involved the training of youth in 2018 in first aid, swift water rescue, research methods, and database management. Researchers also recorded Kaska language terminology and place names of key areas. Water quality and flow/depth gauges were also used to learn more about changes in the Liard River and its tributaries. | | |

| Example of Findings—A key concern in the region is about water levels in the Liard and tributaries; the Dena Kayeh Institute aimed to assess changing water flow through oral histories and the placement/use of water gauges in each key tributary of the main stem of the Liard River as well as in many other tributaries, including Iron Creek Hutchinson Creek, Troutline Creek, and McDame Creek. |

4.9. Treaty 8 Tribal Association of British Columbia

The Treaty 8 Tribal Association represents six First Nations in Northeastern BC. Its membership consists of a Council of Six Treaty 8 Tribal Association Chiefs of member and non-member First Nations. The ethnolinguistic grouping within the eight First Nations includes Sicannie (Sikanni), Slavey, Beaver (Dane-Zaa), Cree, and Saulteau. The communities of the Treaty 8 Tribal Association have always valued the Peace River and its resources as the basis of the culture, economy, and food security. People here have long depended on a diversity of fish species and other wildlife in this region to sustain their families over many generations. The work carried out through Tracking Change built upon, and contributed to, other research and initiatives concerning the impacts of the WAC Bennett Dam and the expansion (“Site C”), which have been ongoing for the last three decades.

Table 9.

Treaty 8 Tribal Association of British Columbia—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

9]).

Table 9.

Treaty 8 Tribal Association of British Columbia—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

9]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| A boat trip and camp were organized to rediscover pre-European fishing methods of the Dane-Zaa, such as netting with natural fibers, fish weirs, and fish traps. A secondary aspect of the project was to identify Cree and Dane-Zaa names and uses of specific fish species. The Eagle Island Fish Camp involved traveling between Hudson’s Hope and Fort St John on the Peace River, an area affected by the WAC Bennett Dam. | place names reflecting social and ecosystem change; species names and conditions; water levels, flow, quality, habitat conditions; climate/development—risks of travel on the lake/rivers, changes in water access, harvest contributions to food security, safety.

| observation/recording of changes on the river and local lakes; training of youth—skill development (navigation, paddling, setting nets); youth well-being; semi-structured interviews with individuals/households; elder–youth knowledge sharing.

|

| Example of Findings—The abundance, diversity, and migration patterns of fish populations in the Peace River have changed as a result of the WAC Bennett Dam and commercial/recreational fish harvesting. In tributary rivers like the Moberly, Halfway, Pine, Sukunka, Murray, Burnt, and Wolverine, it is common knowledge among local fishers that fish populations are in rapid decline. Most fishers believe it is due to overfishing because backcountry roads created open access to once remote fishing spots. This change has been observed since the mid-1960s after the first dam was built on the Peace River (the WAC Bennett) and then again after the second dam was built in 1980 (the Peace Canyon). |

4.10. Mikisew Cree First Nation

Mikisew Cree First Nation (Mikisew) is a Treaty 8 First Nation located in Fort Chipewyan on the Peace–Athabasca Delta and surrounding waters. The heart of their traditional territory is the Peace–Athabasca Delta, which is a UNESCO protected site partly within Wood Buffalo National Park as well as the Athabasca River system, the epicenter of the oil sands region of Alberta. The Mikisew Cree First Nation Government and Industry Relations initiative is a community-based monitoring program established in their region in 2008; the program focuses on providing information to its members on the health of wild foods, safe river navigation (e.g., by marking river channels and hazards), and assessment of other changes in water and ice/snow conditions. The work carried out in 2015–2018 with funding from Tracking Change, built on the strengths of this existing program.

Table 10.

Mikisew Cree First Nation—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

10]).

Table 10.

Mikisew Cree First Nation—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

10]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| The project involved the collection of digital navigation/water-level data on the Athabasca River using a tablet/phone app. | place names; species names and conditions; water levels, quality, habitat conditions; development—risks of travel on the lake/rivers, changes in water access, harvest contributions to food security, safety.

| observation/recording of changes on the river and local lakes; training of youth—skill development (navigation, setting nets, making dry-fish); semi-structured interviews with individuals/households; development of key fish health indicators and research methods; semi-structured interviews with individuals/households; elder–youth knowledge sharing; use of video to record stories and share results of fish and navigation findings.

|

| Example of Findings—Traditional knowledge holders, elders, and Mikisew land users have noted changes in the quality of the water in their harvest areas and negative changes to the abundance of certain animal species, as well as increases in malformations to individuals of a given species. Most notably, Mikisew members have seen a rise in the number of deformities in fish, to the degree that many members no longer consume wild-caught fish. The problem was so acute that in 2008 the Mikisew formed a community-based monitoring program to track changes in Indigenous knowledge indicators of ecosystem health as well as Western science parameters of water quality and animal/fish health. |

4.11. Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta

Treaty 8 territory covers the areas of northern Alberta, Northwestern Saskatchewan, Northeastern British Columbia, and the southwest portion of the Northwest Territories. Historically, the First Nation situated within the basins lived and traveled across the 840,000 km2 area; however, under the terms of the Treaty (and later the signing of the Northwest Transfer Agreement between the federal and provincial government in 1932), First Nations were forced onto a series of small reserves. Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta is an organization representing 24 First Nations living within Alberta borders of the Mackenzie River Basin, including the sub-basins of the Peace, Slave, and Athabasca rivers. Numerous fish species inhabit these sub-basins and are important for subsistence use. There are also Dene/Cree place names documented throughout this study (500+ names) that evidence different kinds of social and ecological change. For example, Swan River in northern Alberta is defined by Indigenous elders as wâpisiw sipiy in Cree and Chi dekali cho eggeze nilehi k’e migeh, which translates as: “where swans used to lay their eggs”. The research carried out by Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta builds upon other projects and governance initiatives led by individual Nations.

Table 11.

Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

11]).

Table 11.

Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta—overview of project (

Figure 1, ref. [

11]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| The project involved the documentation of place names (through elders’ workshops) as well as a boat trip on the Peace River. | place names—ecological and cultural changes; species names, population dynamics, and condition; water levels, quality, habitat conditions; development—risks of travel on the lake/rivers, changes in water access, harvest contributions to food security, safety.

| observation/recording of changes on the river and local lakes; workshops, semi-structured interviews with individuals/households.

|

| Example of Findings—There have been many changes in the Treaty 8 region of Alberta due to resource development including agriculture, forest, pipelines, oil and gas extraction as well as hydroelectric development. These impacts are very visible in many systems including the Athbasca River Watershed and Lesser Slave Lake which elders now describe as destroyed. “The lake, the Lesser Slave Lake. I have seen big changes in my time. I saw it go from a productive lake to a sucker polluted lake. They wiped out everything, and how they wiped out all the different species was they had mink ranches along the lake. And they were harvesting herring out of that lake. Herring is a pretty small fish, so I order to catch it; you need to have a small mesh net. Well, when you have those kinds of nets set out in the lake, you catch everything. That’s how they ended up destroying all the native species of that lake.” (Elder, Sucker Creek First Nation, 2018). |

4.12. Prince Albert Grand Council

The Prince Albert Grand Council (PAGC) is a tribal council representing the band governments of 12 First Nations in the province of Saskatchewan; it was created in 1977 and is one of the largest in Canada. Two interrelated projects occurred in northern Saskatchewan led by the Prince Albert Grand Council. The research took place in Black Lake, northern Saskatchewan, in September 2017. A small group of elders and traditional land users were interviewed about changes in the Athabasca River Watershed. In 2018, a youth camp involving participants from the Prince Albert Grand Council region took place to ensure youth had opportunities to learn from their elders about how to live on the land and cope with changes in the Athabasca River Watershed. A range of themes and indicators of change emerged from these interviews.

Table 12.

Prince Albert Grand Council (

Figure 1, ref. [

12]).

Table 12.

Prince Albert Grand Council (

Figure 1, ref. [

12]).

| Activities | Key Indicators | Monitoring Method |

|---|

| The project involved two phases of interviews with elders about changes occurring in the Athabasca River Watershed as well as a youth camp to share knowledge. | habitat disruption; changes fish diversity/populations; size/fat of fish; condition of fish (e.g., deformities); disturbance from resource development; cancer rates among Denesọłiné peoples; knowledge sharing/research about the impacts of development on fish and human health; water level changes (i.e., upstream hydro projects); sediments in the water; access to traditional hunting and fishing areas; health of drinking water.

| observation/recording of changes on the river and local lakes; workshops, semi-structured interviews with individuals/ households; camp with youth to share knowledge.

|

| Example of Findings—“Our Elders taught us to respect our lands and what it provides for us, in Dene we say ‘nuhech’alanie’, the life path that all of us walk on. We are taught those ways from a young age and carry on those ways for the rest of our lives. We make sure when we take anything from the land, we do not take it all, we also do not destroy the land so that nothing can live on it. The land is who we are. We come from the land and we go back to the land when our journey here is done, this is the Dene way” (Elder Bert Lemaigre from La Loche) [142]. “Not much has changed to this day, we still live off the fish from our lakes. Fish samples are always being taken by different people who work with the department of environment, there are monitoring areas located at specific points around here. These include Cree river, Fond du Lac river, and Stony Rapids where the river goes into the big lake. Samples are taken periodically to see if there are any changes to water etc. two people from each community assist in this and report back to the members about the findings and so forth. From the findings, we have been able to determine that most of the small lakes around Black Lake all have good quality fish in them” (Echodh, 29 September 2017) [142]. |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

A networked approach to community-based monitoring aimed at building knowledge about social–ecological change in the Mackenzie River Basin was described in this paper. The indicators and methodological approaches detailed (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12) were designed locally with a high degree of social and ecological specificity—“one-size does not fit all”. The Indigenous organizations who led work in each region during the 2016–2018 period had a simultaneous interest in meeting local knowledge needs while at the same time contributing to a greater understanding of the larger watershed.

The work builds on a growing literature and practice of community-based monitoring. The work is also inspired by theories of knowledge co-production [

143,

144,

145,

146]. Many Indigenous-led monitoring programs, such as the Arctic Borderlands Ecological Knowledge Co-op [

143], have a long and successful history. These programs have generated knowledge about the impacts of resource development, the dynamics of climate change, and advanced learning on key issues of biodiversity conservation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In addition to producing data and addressing knowledge gaps, many Indigenous-led monitoring programs are expressions of self-determination and sovereignty and represent steps toward the decolonization of conventional institutions and processes of environmental surveillance and management. Despite successes, community-based monitoring is often viewed as too simple and small-in-scale to offer insights into complex and large-scale ecological problems.

This study confronted these critiques by offering “methodological

bricolage” as a unifying framework for the many kinds of indicators, methods, and rules-in-use related to tracking of social and ecological change. Building on previous theory and methodological inquiry in the social sciences, we dismiss the premise of “one-size-fits-all” or a singular template. Based on the learnings of research, we suggest methodological

bricolage can be useful in designing a networked approach to community-based monitoring in large watersheds. In the Mackenzie River Basin specifically, the operationalization of this framework has five steps that create opportunities to support the integration of diverse methods through local projects and share (with the potential for innovation of more/different methods) at larger scales (

Figure 3).

Examples of how 12 Indigenous organizations across the Mackenzie River Basin have generated knowledge about social–ecological change are synthesized in

Table 13. By designing their projects at the local level, Indigenous partners were able to ensure that their own knowledge needs were met (e.g., to support education and local-level learning by documenting use and occupancy, community history) while at the same time contributing to a broader-scale understanding of change in the Basin. While the projects used different methods, the common focus, defined collaboratively at the beginning of the project (

Figure 2), provided the foundation for knitting outcomes together around key questions such as “Can I eat the fish?”, “Can I drink the water?”, and “Can I travel safely on the water/ice?”.

Table 13.

Synthesis table—approach, capacities for monitoring and key indicators.

Table 13.

Synthesis table—approach, capacities for monitoring and key indicators.

| General Method | Examples of Common Approaches to Monitoring | Examples of Common Indicators | Local Learning and Basin-Wide Learning |

|---|

| Harvest Studies | Setting nets in different places/seasons; Harvest recall studies (no. of fish harvested, shared, and consumed);

| Harvest yields/locations (signal differences in population, distribution, species diversity, invasive species); % of harvest to food security (no. of people harvesting in the community);

| Local: Informs harvest decisions about where/when to harvest; Basin: Sharing of knowledge about changes in (upstream/downstream) variabilities and unprecedented changes in species distribution, health, etc.;

|

| Risk Assessment | Assessment of aquatic systems and fish health; Testing for contaminants; Perceptions of the safety of water/ice conditions;

| Fish health (fat/skinny fish, soft/firm flesh, the color of organs, the prevalence of cysts, lesions, deformities); Water quality, level, and flow changes, ice thickness, and water/air temperatures;

| Local: Informs decisions about fish consumption; Basin: Sharing of knowledge about upstream, downstream variabilities leads to a shared understanding of reported/perceived risks across the Basin (may amplify/de-amplify local perceptions);

|

| Place-Name Mapping | | Changes in attributes and meanings of places of ecological and cultural significance; Changes in navigation, drying conditions, and dynamics of water levels/flows;

| |

| Knowledge and Capacity | Semi-structured interviews and “storytelling” about past, present, future; Experiential learning (e.g., canoe trips).

| Diversity/similarity of experiences, observations, and interpretations of change; Individual confidence, sense of self-efficacy for stewardship; Participation in care and stewardship; Youth engagement in teaching–learning.

| Local: Informs decisions about how/who is involved in stewardship; Basin: Informs decisions about how/who engages in stewardship and representation in governance; braiding together of meanings and significance of changes being observed and experienced leads to improved decision-making.

|

There are some similarities and differences in how Indigenous partners approached the practice of monitoring. The individual projects were built on the strengths, assets, and capacities of the individual organizations, and addressed knowledge gaps and the needs of local communities (e.g., need for information about changing water levels, changes in the health of fish upstream). In that context, there was a spectrum in the kind of work that was completed through the project, such that each organization carried out monitoring in its own way. For example, Indigenous place names were of common importance across the Basin. In some cases, they had already been documented, but in other cases, (e.g., Treaty 8 region of Alberta) place-name work was done through the Tracking Change project. Another variation was in the degree of utilization of university resources, including graduate students. In some areas graduate students played a key role in the research (e.g., in risk perception studies), but in others the work was carried out almost entirely by local researchers and Indigenous organization staff. Given the range of capacity available in local institutions, the ability to draw on graduate students and other university resources was essential for making sure that each local project was able to set and achieve ambitious goals rather than being limited by internal capacity.

A cross-section of qualitative versus quantitative methods was used. Some indicators were quantitative (e.g., number of fish harvested, diversity of species, length–weight ratio), and many were qualitative (e.g., access to fishing areas). In some communities, the use of surveys was helpful to documenting quantitative evidence of particular kinds of problems, such as the risks of drinking water as experienced by different age groups, genders, and socioeconomic groups. In other areas, the work was mainly qualitative (e.g., storytelling); in some, it was entirely experiential and focused on the teaching and education of youth. There were large overlaps in the indicators used (e.g., those for tracking fish health).

Table 13 presents a summary and synthesis of the various methods and indicators used to address the parameters of interest to the communities involved. As noted in

Figure 3, the intent of the approach was to reflect local priorities and contexts while also allowing for the sharing of ideas, methods, and results to create local as well as basin-wide learning. We suggest that this table be used as an exemplar or model, rather than as a recipe. Taken together and operationalized at both the local and basin-wide scales, the indicators yield data about the trends and patterns of greatest meaning and significance to the First Nations and Inuvialuit.

All the projects were rooted to place. Whether through the documentation of oral histories, mapping, or experiential learning activities (e.g., at fish camps), all the methods as well as outcomes had a strong degree of cultural and ecological specificity. Intergenerational knowledge sharing among elders, other knowledge holders, and youth was also a common dynamic in all the projects. The learning that was facilitated strongly related to practices of surviving on the land (e.g., being able to read weather patterns on Great Slave Lake) or to passing on skills for food security (e.g., setting nets). There was a strong focus on answering key questions of immediate concern to safety, food security, and travel routes, as illustrated by the research on drinking water quality, fish health, permafrost thaw and slumping, and ice conditions.

Tight coupling between knowledge generation, on the one hand, and social learning, on the other, was another important strength of the monitoring approaches developed. For example, the work carried out by Mikisew Cree to track boat travel on the Athabasca River was done in such a way that knowledge was instantly conveyed back to boaters through a digital navigation smartphone app. Similarly, knowledge about fish health was immediately shared with those attending fish camps such as the ones held in the Gwich’in and Inuvialuit regions. Other feedbacks were slower and addressed longer-term and multi-layered problems. For example, the documentation of Dene and Cree place names in Alberta, coupled with the interpretation of their meanings, took many months but provided a tremendous depth of insight about ecological and social changes in this part of the Basin.

There were similarities between Tracking Change’s experiences and other kinds of monitoring approaches used in other regions of Canada and globally. The social–ecological lens, which is rooted in the belief that people and nature are strongly interconnected, was visible in the monitoring work led by many other Indigenous peoples, whether about fisheries, forests, wildlife, or in the study of climate change, mining, or hydro-development [

6,

57,

80,

146]. The large number and diversity of indicators revealed here (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12) are consistent with the findings of our companion projects in the Amazon Basin (Tapajos River) and the Mekong Basin [

124,

147,

148,

149,

150]. The embrace of people as monitors of change—as experts with memories, observations, and the capacity to track changes in their environment through their own socio-cultural practices—was also common, as comprehensively illustrated in the Results section and in the synthesis (

Table 13).

Cumulatively, the knowledge that was generated provides a different, though complementary, understanding of the Mackenzie River Basin from that produced through conventional scientific monitoring. Through this work, we understand that the Basin is not simply a biophysical system but a social–ecological system, a cultural landscape. The Tracking Change project is unique in its recognition of local meanings of change in the various communities as highly normative. That is, the changes being tracked and their meaning and significance depend on the individual, the social group, and the location of the community in the Basin. As such, the work embraces and makes transparent the subjectivities inherent in the monitoring process, rather than assuming a pretense of uniformity and objectivity.

6. Conclusions

What we learned from the Mackenzie Basin, and from our companion projects in the Amazon and the Mekong, may also apply to other locations and to diverse resource types as well from water resources [

14] to edible seaweed harvesting [

51]. Community-based monitoring provides new insights and perhaps a richer understanding than that produced through scientific monitoring, but there are commonalities and complementarities as well. Such complementarities raise the possibility of co-production of knowledge, defined as the collaborative process of using a plurality of knowledge sources and types together to address a problem [

144,

145].

For example, Cobb and colleagues compared environmental quality indicators used in conventional science vs. Indigenous knowledge in monitoring contaminant-related effects in fish and marine mammals in the Canadian North [

151]. Based on a variety of data sources from the Canadian Arctic, Indigenous hunters were found to be using indicators that were comparable to those used in ecotoxicology at the individual, population, and community levels—but not at biochemical and cellular levels [

151]. The overlap in the two kinds of indicators was about 50 percent, except that the Indigenous indicators were qualitative, more numerous and used as a suite. This evidence, coupled with the outcomes of this paper, raises the possibility of using community-based monitoring as a cost-effective way of tracking certain indicators and obtaining qualitative data on a richer set of indicators than otherwise possible, thus facilitating knowledge co-production [

151,

152].

While governments and managers may view “cost-effectiveness” as a key benefit, for Indigenous peoples the deeper value of community-based monitoring lies in opportunities to decolonize how evidence about large watersheds is documented, and thereby to foster greater self-determination in the management of lands and resources. Participatory monitoring brings the additional benefits of including local people in research and management, building local capacity, raising awareness of management needs, and helping with adaptation to change. Importantly, community-based approaches are people-centred in that they serve and involve communities directly. Our project shows the feasibility of peoples and communities tracking environmental changes that are important for them, their livelihoods, and their culture. Scientific monitoring is not designed to respond to local needs and priorities, but community-based monitoring is, especially if it is done on the community’s own terms [

153,

154].

Six specific conclusions from our experience may be relevant to others planning or conducting monitoring programs at the river Basin or ecosystem scale that seek to engage local communities:

Making the space for communities to determine the terms of their engagement (what they monitor, how, by whom, etc.) is essential to building local commitment. This fosters local initiative, as a part of decolonization, and the application of monitoring efforts and results for their own needs.

Sharing of ideas and experiences among communities is essential to encourage connections and for communities to inspire one another; this takes planning and effort (i.e., it will not happen by chance). The diversity of methods and tools used by the communities for monitoring may be considered methodological bricolage; although seemingly disjointed, they can effectively work together for the big picture.

Commonalities among communities (e.g., ecology, culture, economy, etc.) are likely to lead to many common elements among community-run monitoring programs, despite differences in approach. These commonalities, when networked, help build a Basin-wide understanding while retaining the advantages of

bricolage (

Figure 3).

Communities and organizations will have different levels of capacity for monitoring. There will be capacity development (capacity-building) needs, as determined by the community. These needs can be met by supporting research organizations and government agencies. As Indigenous monitoring serves information needs for management, there should be funding support commensurate with services provided. Technical support (equipment; information processing) and research personnel (e.g., graduate students) should also be available.

Monitoring results and experiences belong to the community or community organization; it is intellectual property. Therefore, it is the communities and Indigenous organizations which should decide how to share those results and experiences, and where possible, take the lead in doing so.

Basin-wide understanding emerges from a networking of local and regional findings. A monitoring network is also a social network, requiring trust and understanding. These do not happen by themselves, so planning and effort should be invested to build them among those involved. Our project shows that different Indigenous peoples can work together harmoniously. But Basin-wide management also involves government managers, requiring the development of trust and understanding within this wider network as well.

With these conclusions in mind, community-based monitoring may be thought of as a way to decolonize old and colonial systems that undermined societies, cultures and ecosystems [

155]. These considerations have contributed to the idea that community-based approaches can be used to monitor and manage of watersheds. Many river systems, including the Mackenzie, Amazon and Mekong, are under growing ecological and socio-economic stresses as a result of climate change, hydroelectric projects, other resource development activities. Research gaps, including the lack of longitudinal data and of the interrelations between social and ecological change, are well known problems that complicate watershed governance globally [

156,

157]. We suggest that networked community-based monitoring, embracing a diversity of approaches and methods, including especially those based on the knowledge, practices, and beliefs of Indigenous peoples, can be a model for effective, efficient, and action-oriented monitoring of watersheds and other large social-ecological systems.