The Dynamics of Financial Development, Government Quality, and Economic Growth in Different Groups of Economies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Model of the Study

3. Results and Discussion

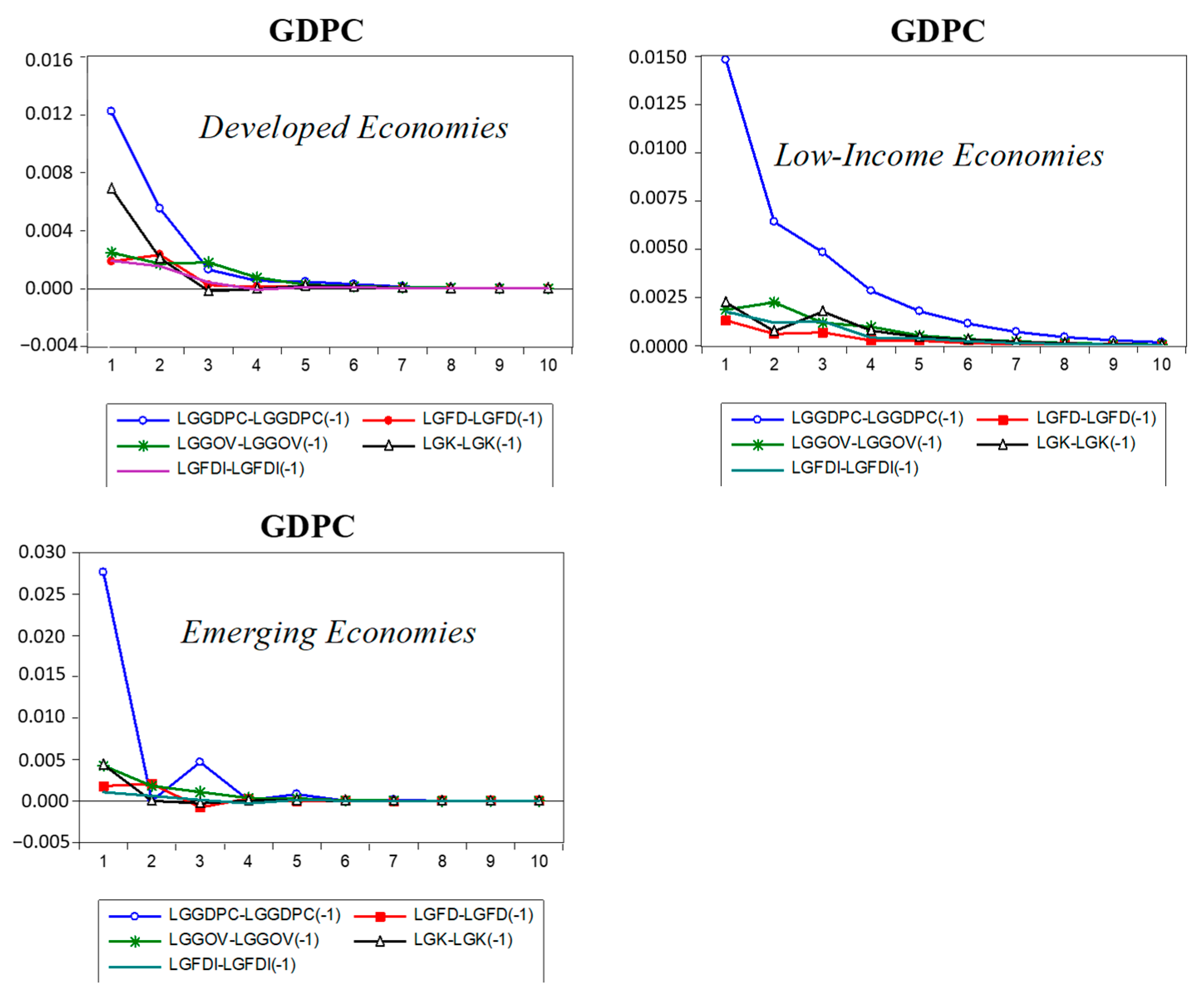

3.1. Impulse Response Function (IRF)

3.2. Variance Decomposition

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balcilar, M.; Gupta, R.; Ma, W.; Makena, P. Income inequality and economic growth: A reexamination of theory and evidence. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, A. Government Expenditure, Governance and Economic Growth. Comp. Econ. Stud. 2009, 51, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, T.W. Economic growth and capital accumulation. Econ. Rec. 1956, 32, 334–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Legal Determinants of External Finance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.-H.; Lee, C.-C. Same Financial Development yet Different Economic Growth: Why? J. Money Credit Bank 2006, 38, 1907–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. Introduction to economic growth. J. Econ. Theory 2012, 147, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A. Foreign direct investments, institutional quality, and economic growth. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2019, 28, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hulten, C.R. Infrastructure Capital and Economic Growth: How Well You Use It May Be More Important than How Much You Have. NBER Working Paper 5847. December 1996. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w5847 (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Jung, J. Institutional Quality, FDI, and Productivity: A Theoretical Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunieda, T.; Takahashi, M. Inequality and institutional quality in a growth model. Evol. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutan, A.M.; Samargandi, N.; Sohag, K. Does Institutional Quality Matter for Financial Development and Growth? Further Evidence from MENA Countries. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2017, 56, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, R.L.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Law and finance. J. Political Econ. 1998, 106, 1113–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-S. Bank-based and market-based financial systems: Time-series evidence. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2012, 20, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.W.; Fung, M.K.; Leung, M.-K. Finance–growth nexus in China from an endogenous switching perspective. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2018, 27, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. The impact of financial development on economic growth in middle-income countries. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2019, 59, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomp, J.; de Haan, J. Bank Regulation, the Quality of Institutions, and Banking Risk in Emerging and Developing Countries: An Empirical Analysis. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2014, 50, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnal, M.; Yaya, M.E. Political Institutions, Trade Openness, and Economic Growth: New Evidence. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2015, 51, 1276–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, K.; Shams, S.M.R.; Omar, N.; Chandrarin, G. Comparative study on finance-growth nexus in Malaysia and Indonesia: Role of institutional quality. Strateg. Chang. 2019, 28, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraay, A.; Kaufmann, D.; Mastruzzi, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. World Bank Policy Reseach Working Paper 5430. September 2010. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/3913 (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Katsiaryna, S. Introducing a New Broad-Based Index of Financial Development1; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carr, D.L.; Markusen, J.R.; Maskus, K.E. Estimating the Knowledge-Capital Model of the Multinational Enterprise. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.-H.; Lin, S.-C.; Suen, Y.-B. Dynamic effects of trade openness on financial development. Econ. Model. 2010, 27, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safkaur, O.; Sagrim, Y. Impact of Human Resources Development on Organizational Financial Performance and Its Impact on Good Government Governance. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2019, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cobb, C.W.; Douglas, P.H. A Theory of Production. Am. Econ. Rev. 1928, 18, 139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.; Acquah, A.M. Re-examining the causal relationships among FDI, economic growth and financial sector development in Africa. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2021, 35, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C. Foreign direct investment, informality and technology transfer. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. General diagnostic tests for cross-sectional dependence in panels. Empir. Econ. 2004, 60, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Breusch, T.S.; Pagan, A.R. The Lagrange Multiplier Test and its Applications to Model Specification in Econometrics. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1980, 47, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitung, J.; Pesaran, M.H. Unit roots and cointegration in panels. In The Econometrics of Panel Data; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 279–322. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maio, F.; Rem, P.C.; Baldé, K.; Polder, M. Measuring resource efficiency and circular economy: A market value approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, F.; Hassapis, C.; Philippas, N.; Tsionas, M. Foreign Direct Investment Determinants in OECD and Developing Countries. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2017, 21, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bist, J.P. Financial development and economic growth: Evidence from a panel of 16 African and non-African low-income countries. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2018, 6, 1449780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mtar, K.; Belazreg, W. Causal Nexus Between Innovation, Financial Development, and Economic Growth: The Case of OECD Countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Bader, S.; Abu-Qarn, A.S. Financial Development and Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence from Six MENA Countries. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2008, 12, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samargandi, N.; Fidrmuc, J.; Ghosh, S. Is the Relationship Between Financial Development and Economic Growth Monotonic? Evidence from a Sample of Middle-Income Countries. World Dev. 2015, 68, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mushtaq, S. Causality between bank’s major activities and economic growth: Evidences from Pakistan. Financ. Innov. 2016, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jindra, C.; Vaz, A. Good governance and multidimensional poverty: A comparative analysis of 71 countries. Governance 2019, 32, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, T.D.; Bui, T.M.H. Government size, public governance and private investment: The case of Vietnamese provinces. Econ. Syst. 2017, 41, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chortareas, G.; Magkonis, G.; Moschos, D.; Panagiotidis, T. Financial Development and Economic Activity in Advanced and Developing Open Economies: Evidence from Panel Cointegration. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2015, 19, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asif, M.; Jan, S.U.; Iqbal, S. Oil prices movements and industry stock returns: Evidence from pakistan stock exchange (PSX). Gomal Univ. J. Res. 2021, 37, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripamonti, A. Financial institutions, asymmetric information and capital structure adjustments. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2020, 77, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayungbo, D.O.; Quadri, A. Remittances, financial development and economic growth in sub-Saharan African countries: Evidence from a PMG-ARDL approach. Financ. Innov. 2019, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, Z. Trade openness, financial openness, and financial development in China. J. Int. Money Financ. 2015, 59, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajda-Lichy, M.; Kawa, P.; Fijorek, K.; Denkowska, S. Trade Openness and Financial Development in the New EU Member States: Evidence from a Granger Panel Bootstrap Causality Test. East. Eur. Econ. 2020, 58, 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, C.R.; Brue, S.L.; Flynn, S.M. Economics: Principles, Problems, and Policies; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy, V.; Dharani, M. The dynamics of finance-growth nexus in advanced economies. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2019, 64, 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünver, M.; Koyuncu, J.Y. The impact of poverty on corruption. J. Econ. Libr. 2016, 3, 632–642. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A. Governance and growth: Causality which way? Evidence for the world, in brief. World Bank Febr. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Squicciarini, M.P. Devotion and development: Religiosity, education, and economic progress in nineteenth-century France. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 3454–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | LLC Test | IPS Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Level | ||||

| t Statistics | p Value | t Statistics | p Value | ||

| Developed Economies | |||||

| FD | −5.79231 | 0.0000 | −6.20031 | 0.0000 | |

| FDI | −5.72933 | 0.0000 | −7.52109 | 0.0000 | |

| GDPC | −5.50230 | 0.0000 | 0.06800 | 0.5271 | |

| GOV | −1.97310 | 0.0242 | −0.5288 | 0.2985 | |

| HC | −3.39426 | 0.0003 | −1.80776 | 0.0353 | |

| INF | −8.17542 | 0.0000 | −7.27809 | 0.0000 | |

| INVST | −5.03218 | 0.0000 | −5.04214 | 0.0000 | |

| TR | −3.11912 | 0.0009 | 0.26618 | 0.6050 | |

| Emerging Economies | |||||

| FD | −2.54341 | 0.0055 | 0.31628 | 0.6241 | |

| FDI | −3.19979 | 0.0007 | −4.73406 | 0.0000 | |

| GDPC | −1.27848 | 0.1005 | 5.02833 | 1.0000 | |

| GOV | −1.07594 | 0.1410 | 0.30664 | 0.6204 | |

| HC | −2.00579 | 0.0224 | 2.42936 | 0.9924 | |

| INF | −6.29176 | 0.0000 | −6.87370 | 0.0000 | |

| INVST | −4.32014 | 0.0000 | −4.92830 | 0.0000 | |

| TR | −3.10209 | 0.0010 | −1.67872 | 0.0466 | |

| Low-Income Economies | |||||

| FD | 0.40621 | 0.6577 | 1.35785 | 0.9127 | |

| FDI | −2.22635 | 0.0130 | −3.36606 | 0.0004 | |

| GDPC | −0.28657 | 0.3872 | 7.31410 | 1.0000 | |

| GOV | −1.91996 | 0.0274 | −0.92506 | 0.1775 | |

| HC | −6.27756 | 0.0000 | −1.81686 | 0.0346 | |

| INF | −8.72234 | 0.0000 | −8.78923 | 0.0000 | |

| INVST | −1.62638 | 0.0519 | −1.58367 | 0.0566 | |

| TR | −2.47935 | 0.0066 | −0.14355 | 0.4429 | |

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev | Minimum | Maximum | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed Economies | |||||

| FD | 0.643964 | 0.193644 | 0.111755 | 1.00000 | 805 |

| FDI | 8.449808 | 27.95833 | −58.32288 | 451.7155 | 805 |

| GDPC | 38651.65 | 19957.23 | 5329.849 | 111968.3 | 805 |

| GOV | 1.275407 | 0.419574 | 0.156203 | 1.969566 | 805 |

| HC | 1749.888 | 7653.872 | 79.90216 | 49440.97 | 805 |

| INF | 2.250779 | 2.237838 | −4.478103 | 17.61047 | 805 |

| Capital (K) | 23.45073 | 4.410587 | 10.21701 | 41.44911 | 805 |

| TR | 114.0559 | 85.28719 | 18.34896 | 442.6200 | 805 |

| Emerging Economies | |||||

| FD | 0.336783 | 0.147256 | 0.025606 | 0.753043 | 920 |

| FDI | 3.160393 | 5.426509 | −46.76922 | 55.07590 | 920 |

| GDPC | 10457.80 | 12811.78 | 711.9288 | 69679.09 | 920 |

| GOV | −0.238283 | 0.601833 | −1.904464 | 1.287036 | 920 |

| HC | 84.37340 | 20.08401 | 9.058750 | 123.2299 | 920 |

| INF | 7.739318 | 8.050081 | −9.797647 | 39.66936 | 920 |

| Capital (K) | 25.07472 | 7.305811 | 9.481002 | 57.99043 | 920 |

| TR | 72.89570 | 35.76600 | 15.63559 | 220.4074 | 920 |

| Low-income Economies | |||||

| FD | 0.130491 | 0.063930 | 0.000000 | 0.470773 | 920 |

| FDI | 3.827798 | 5.650260 | −37.15476 | 50.63641 | 920 |

| GDPC | 1072.161 | 647.7313 | 187.5167 | 4210.042 | 920 |

| GOV | −0.772990 | 0.450865 | −2.100317 | 0.251952 | 920 |

| HC | 45.60266 | 23.16574 | 4.979884 | 107.2295 | 920 |

| INF | 8.917705 | 8.594494 | −8.974740 | 51.48755 | 920 |

| Capital (K) | 24.14511 | 8.149936 | 1.525177 | 60.15617 | 920 |

| TR | 71.27614 | 35.01788 | 0.167418 | 200.3846 | 920 |

| Variance Decomposition of GDPC | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed Economies | Emerging Economies | Low-Income Economies | ||||||||||

| Period | S.E. | GDPC | FD | GOV | S.E. | GDPC | FD | GOV | S.E. | GDPC | FD | GOV |

| 1 | 0.012 | 98.111 | 1.888 | 0.000 | 0.026 | 99.097 | 0.902 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 100.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.020 | 96.719 | 3.209 | 0.070 | 0.037 | 98.022 | 1.598 | 0.379 | 0.026 | 99.789 | 0.010 | 0.199 |

| 3 | 0.026 | 96.280 | 3.538 | 0.181 | 0.045 | 97.521 | 1.809 | 0.668 | 0.036 | 99.544 | 0.063 | 0.391 |

| 4 | 0.031 | 96.140 | 3.536 | 0.323 | 0.051 | 97.183 | 1.920 | 0.895 | 0.044 | 99.310 | 0.161 | 0.528 |

| 5 | 0.036 | 96.101 | 3.402 | 0.496 | 0.057 | 96.925 | 1.985 | 1.088 | 0.052 | 99.073 | 0.306 | 0.620 |

| 6 | 0.039 | 96.084 | 3.213 | 0.701 | 0.062 | 96.706 | 2.026 | 1.266 | 0.058 | 98.818 | 0.498 | 0.683 |

| 7 | 0.043 | 96.056 | 3.005 | 0.938 | 0.067 | 96.508 | 2.054 | 1.437 | 0.064 | 98.538 | 0.734 | 0.727 |

| 8 | 0.046 | 96.000 | 2.793 | 1.206 | 0.071 | 96.320 | 2.072 | 1.606 | 0.070 | 98.227 | 1.013 | 0.758 |

| 9 | 0.049 | 95.906 | 2.588 | 1.505 | 0.075 | 96.139 | 2.085 | 1.774 | 0.075 | 97.883 | 1.333 | 0.782 |

| 10 | 0.051 | 95.770 | 2.395 | 1.833 | 0.078 | 95.961 | 2.094 | 1.943 | 0.079 | 97.507 | 1.690 | 0.801 |

| Variance Decomposition of Financial Development | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 100.00 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 100.00 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 1.170 | 98.829 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.011 | 0.353 | 99.634 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.614 | 99.174 | 0.210 | 0.007 | 1.853 | 97.853 | 0.293 |

| 3 | 0.013 | 0.642 | 99.331 | 0.025 | 0.013 | 0.790 | 98.794 | 0.414 | 0.008 | 2.429 | 97.117 | 0.452 |

| 4 | 0.015 | 0.843 | 99.116 | 0.040 | 0.015 | 0.901 | 98.519 | 0.578 | 0.009 | 2.945 | 96.471 | 0.583 |

| 5 | 0.017 | 0.981 | 98.959 | 0.059 | 0.017 | 0.979 | 98.297 | 0.722 | 0.010 | 3.408 | 95.904 | 0.687 |

| 6 | 0.019 | 1.082 | 98.837 | 0.080 | 0.018 | 1.041 | 98.101 | 0.857 | 0.011 | 3.836 | 95.387 | 0.776 |

| 7 | 0.020 | 1.158 | 98.738 | 0.103 | 0.020 | 1.093 | 97.918 | 0.988 | 0.012 | 4.241 | 94.903 | 0.855 |

| 8 | 0.021 | 1.218 | 98.651 | 0.130 | 0.021 | 1.139 | 97.740 | 1.120 | 0.012 | 4.630 | 94.442 | 0.927 |

| 9 | 0.022 | 1.267 | 98.573 | 0.159 | 0.022 | 1.181 | 97.565 | 1.252 | 0.013 | 5.008 | 93.995 | 0.995 |

| 10 | 0.023 | 1.309 | 98.499 | 0.191 | 0.023 | 1.221 | 97.390 | 1.387 | 0.014 | 5.380 | 93.560 | 1.059 |

| Variance Decomposition of Governance | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 0.010 | 3.267 | 0.106 | 96.625 | 0.021 | 2.701 | 0.545 | 96.753 | 0.018 | 1.346 | 0.030 | 98.622 |

| 2 | 0.015 | 4.469 | 0.236 | 95.294 | 0.032 | 2.814 | 0.745 | 96.439 | 0.029 | 1.951 | 0.098 | 97.950 |

| 3 | 0.019 | 5.151 | 0.273 | 94.574 | 0.041 | 2.914 | 0.806 | 96.279 | 0.037 | 2.398 | 0.134 | 97.467 |

| 4 | 0.022 | 5.528 | 0.269 | 94.201 | 0.048 | 2.990 | 0.826 | 96.182 | 0.043 | 2.716 | 0.171 | 97.112 |

| 5 | 0.024 | 5.733 | 0.249 | 94.016 | 0.054 | 3.056 | 0.830 | 96.112 | 0.048 | 2.940 | 0.210 | 96.849 |

| 6 | 0.027 | 5.839 | 0.223 | 93.936 | 0.060 | 3.118 | 0.827 | 96.054 | 0.053 | 3.099 | 0.252 | 96.647 |

| 7 | 0.029 | 5.885 | 0.197 | 93.916 | 0.064 | 3.176 | 0.819 | 96.003 | 0.057 | 3.214 | 0.299 | 96.486 |

| 8 | 0.031 | 5.894 | 0.174 | 93.931 | 0.069 | 3.233 | 0.810 | 95.956 | 0.060 | 3.299 | 0.349 | 96.351 |

| 9 | 0.033 | 5.878 | 0.155 | 93.966 | 0.073 | 3.288 | 0.798 | 95.912 | 0.063 | 3.363 | 0.402 | 96.234 |

| 10 | 0.035 | 5.845 | 0.141 | 94.013 | 0.076 | 3.343 | 0.787 | 95.869 | 0.066 | 3.412 | 0.459 | 96.127 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iqbal, S.; Khan, A.Q.; Khan, M.Y.; Al-Aali, L. The Dynamics of Financial Development, Government Quality, and Economic Growth in Different Groups of Economies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7573. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147573

Iqbal S, Khan AQ, Khan MY, Al-Aali L. The Dynamics of Financial Development, Government Quality, and Economic Growth in Different Groups of Economies. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7573. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147573

Chicago/Turabian StyleIqbal, Shahid, Abdul Qayyum Khan, Muhammad Yar Khan, and Lamya Al-Aali. 2021. "The Dynamics of Financial Development, Government Quality, and Economic Growth in Different Groups of Economies" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7573. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147573

APA StyleIqbal, S., Khan, A. Q., Khan, M. Y., & Al-Aali, L. (2021). The Dynamics of Financial Development, Government Quality, and Economic Growth in Different Groups of Economies. Sustainability, 13(14), 7573. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147573