Digital Innovation for the Sustainability of Reshoring Strategies: A Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

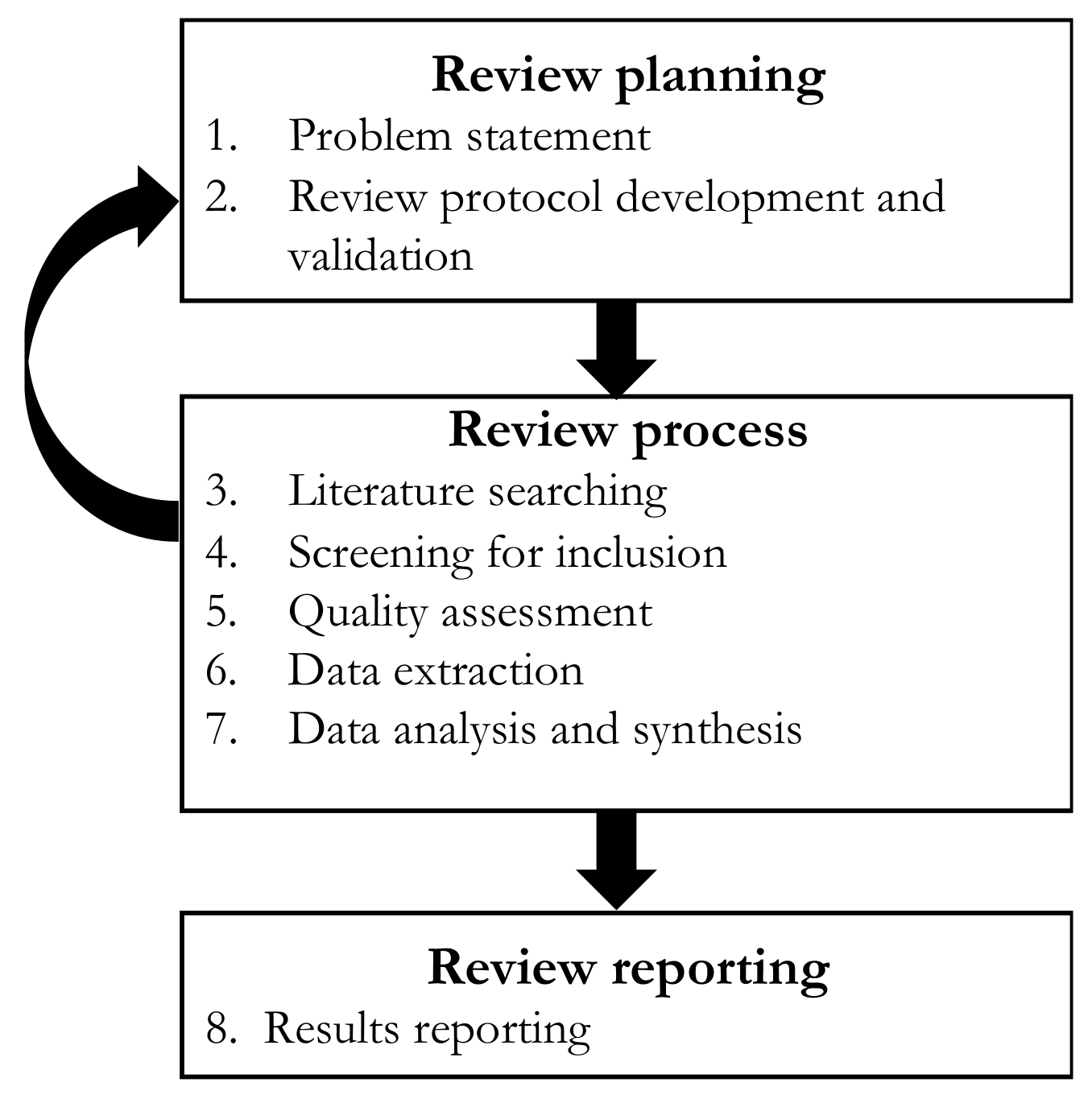

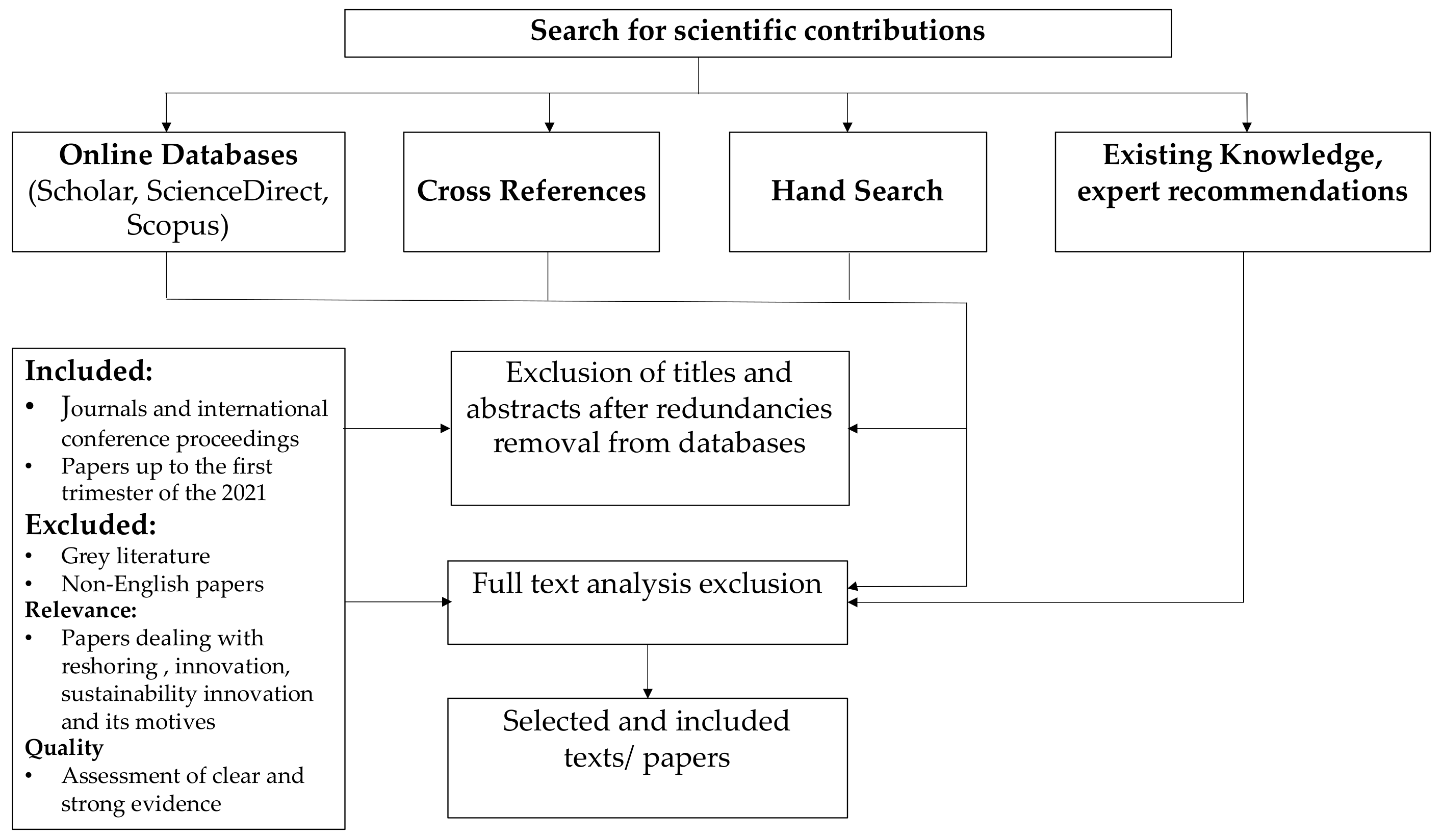

2. Materials and Methods

- RQ1: Are sustainability issues among the motives/drivers at the core of reshoring decisions?

- RQ2: Does digital innovation contribute to the development and the enactment of sustainable reshoring strategies?

Research Strategy

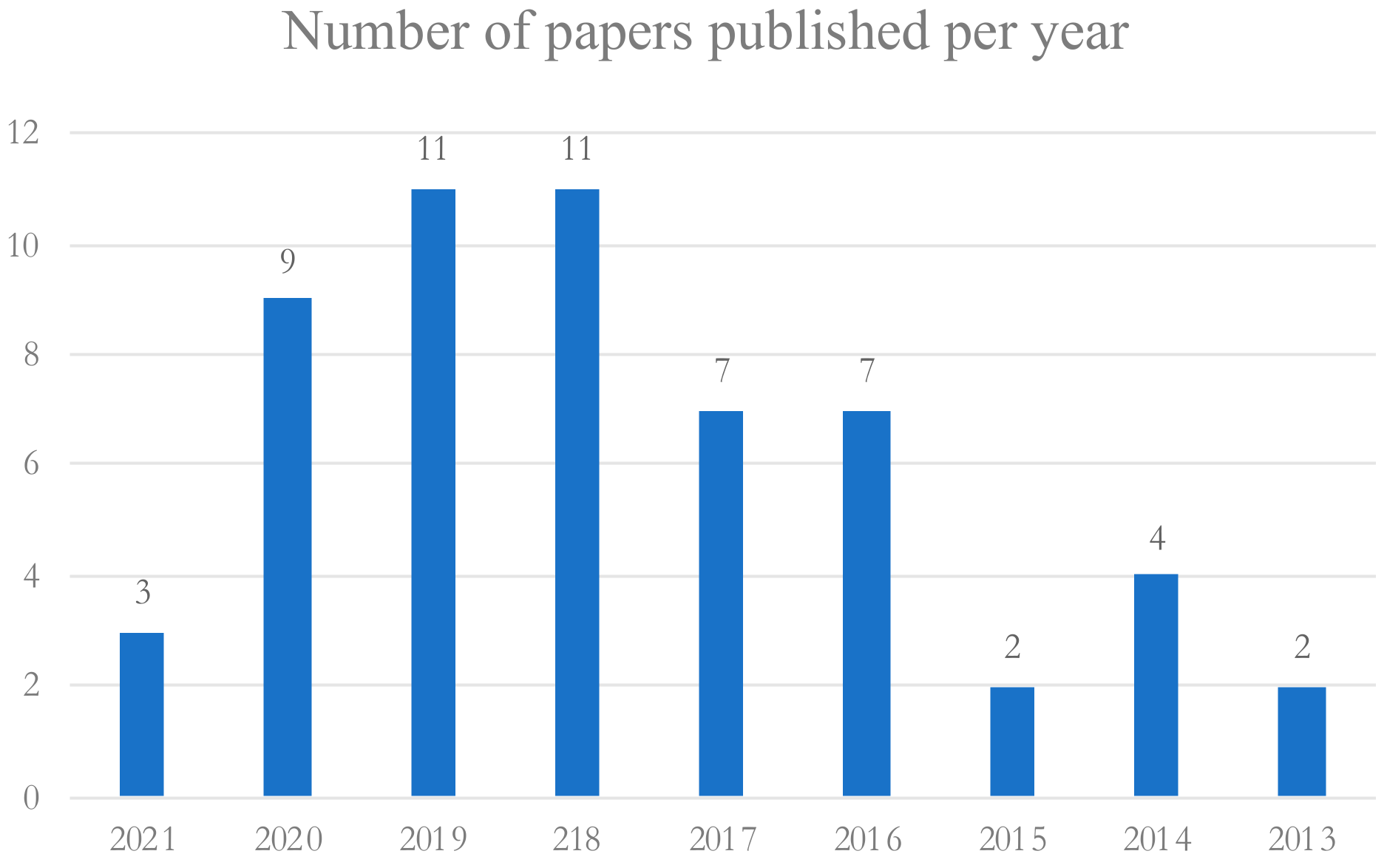

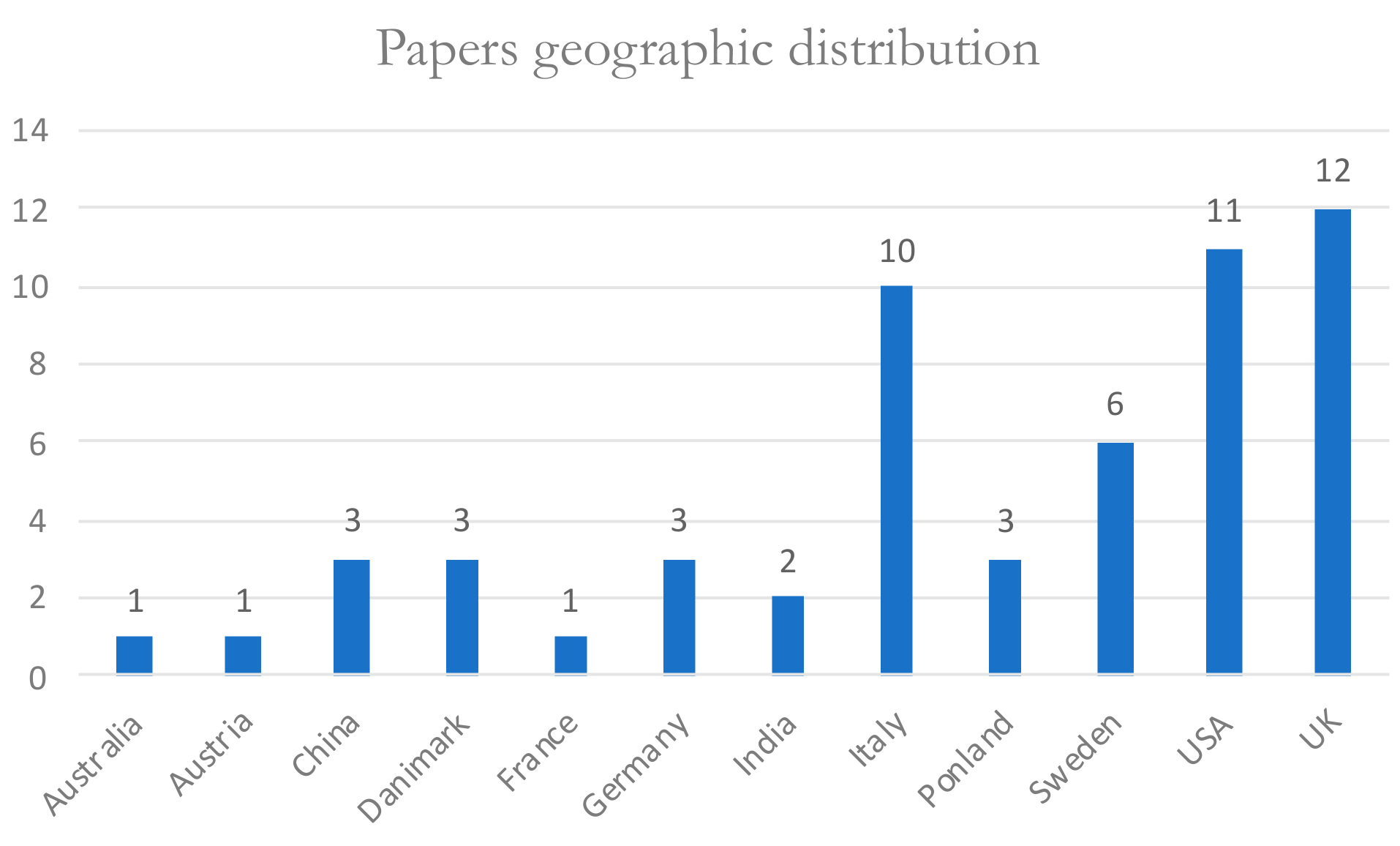

3. Literature Review Results

4. Discussion

4.1. “Who” Takes Reshoring Decisions

4.2. “What” Reshoring Is

4.3. “Where” Reshoring

4.4. “When” Reshoring

4.5. “Why” Reshoring

4.6. “How” to Enact Reshoring Decisions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiesmann, B.; Snoei, J.R.; Hilletofth, P.; Eriksson, D. Drivers and barriers to reshoring: A literature review on offshoring in reverse. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2017, 29, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, V.; Budhwar, P.; Temouri, Y.; Malik, A.; Tarba, S. Investigating investments in agility strategies in overcoming the global financial crisis—The case of Indian IT/BPO offshoring firms. J. Int. Manage. 2020, 27, 100–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Gunasekaran, A.; Dekkers, R.; Pereira, V. Outsourcing and offshoring decision making. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 4187–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levine, L. Offshoring (or Offshore Outsourcing) and Job Loss Among US Workers. 2012. Available online: www.crs.gov (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Tate, W.L. Offshoring and reshoring: US insights and research challenges. J. Purch. Supply Manage. 2014, 20, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffelli, A.; Colini, R.; Orzes, G.; Dotti, S. Open the box: A behavioural perspective on the reshoring decision-making and implementation process. J. Purch. Supply Manage. 2020, 26, 600–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, P.; Ciabuschi, F.; Fratocchi, L.; Vignoli, M. What do we know about manufacturing reshoring? J. Glob. Op. Strateg. Sour. 2018, 11, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellram, L.M.; Tate, W.L.; Petersen, K.J. Offshoring and reshoring: An update on the manufacturing location decision. J. Supply Chain Manage. 2013, 49, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratocchi, L.; Ancarani, A.; Barbieri, P.; Di Mauro, C.; Nassimbeni, G.; Sartor, M.; Zanoni, A. Motivations of manufacturing reshoring: An interpretative framework. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Log. Manage. 2013, 46, 98–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, C.; Fratocchi, L.; Orzes, G.; Sartor, M. Offshoring and backshoring: A multiple case study analysis. J. Purch. Supply Manage. 2018, 24, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatanesi, B.; Arauzo-Carod, J.M. Backshoring and nearshoring: An overview. Growth Change 2019, 50, 806–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vona, R.; Cosimato, S. Green operation management. In Management Della Produzione e Della Logistica; Vona, R., Di Paola, N., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cosimato, S.; Troisi, O. Green supply chain management: Practices and tools for logistics competitiveness and sustainability. The DHL case study. TQM J. 2015, 27, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzes, G.; Sarkis, J. Reshoring and environmental sustainability: An unexplored relationship? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratocchi, L.; Di Stefano, C. Does sustainability matter for reshoring strategies? A literature review. J. Glob. Op. Strateg. Sour. 2019, 12, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Foropon, C.; Godinho Filho, M. When titans meet—Can industry 4.0 revolutionise the environmentally-sustainable manufacturing wave? The role of critical success factors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 132, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, L.; Filippini, R. Organizational and managerial challenges in the path toward Industry 4.0. Eur. J. Innov. Manage. 2019, 22, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boute, R.N.; Disney, S.M.; Gijsbrechts, J.; Van Mieghem, J.A. Dual sourcing and smoothing under nonstationary demand time series: Reshoring with speed factories. Manage. Sci. 2021, 1, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kinkel, S.; Capestro, M.; Di Maria, E. Artificial intelligence and backshoring strategies: A German-Italian comparison. In Handbook of Research on Applied AI for International Business and Marketing Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 227–255. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paola, N.; Vona, R. Management delle imprese di logistica: Razionalità e innovazione nella sfida per la competitività (Logistic providers management: Competing between rationality and innovation). Fin. Mark. Prod. 2013, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ancarani, A.; Di Mauro, C. Reshoring and Industry 4.0: How often do they go together? IEEE Eng. Manage. Rev. 2018, 46, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachs, B.; Kinkel, S.; Jäger, A. Bringing it all back home? Backshoring of manufacturing activities and the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies. J. World Bus. 2019, 54, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fratocchi, L.; Di Mauro, C.; Barbieri, P.; Nassimbeni, G.; Zanoni, A. When manufacturing moves back: Concepts and questions. J. Purch. Supply Manage. 2014, 20, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.V.; Esenduran, G.; Rungtusanatham, M.J.; Skowronski, K. Why in the world did they reshore? Examining small to medium-sized manufacturer decisions. J. Oper. Manage. 2017, 49, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grappi, S.; Romani, S.; Bagozzi, R.P. Reshoring from a demand-side perspective: Consumer reshoring sentiment and its market effects. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mentzer, J.T.; Kahn, K.B. Forecasting technique familiarity, satisfaction, usage, and application. J. Forecast. 1995, 14, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Young, M.; Partington, D.; Bessant, J.; Sapsed, J. Knowledge management routines for innovation projects: Developing a hierarchical process model. Int. J. Innov. Manage. 2003, 7, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plan. Edu. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradlou, H.; Tate, W. Reshoring and additive manufacturing. World Rev. Intermod. Transport. Res. 2018, 7, 241–263. [Google Scholar]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, A.; Leat, M.; Hudson-Smith, M. Making connections: A review of supply chain management and sustainability literature. Supply Chain Manage. Int. J. 2012, 17, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Apaydin, M. A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. J. Manage. Stud. 2010, 47, 1154–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentoft, J.; Olhager, J.; Heikkilä, J.; Thoms, L. Manufacturing backshoring: A systematic literature review. Oper. Manage. Res. 2016, 9, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Gold, S. Conducting content-analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management. Supply Chain Manage. Int. J. 2012, 2, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Nilsson, F. Themes and challenges in making supply chains environmentally sustainable. Supply Chain Manage. Int. J. 2012, 17, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoejmose, S.U.; Adrien-Kirby, A.J. Socially and environmentally responsible procurement: A literature review and future research agenda of a managerial issue in the 21st century. J. Purch. Supply Manage. 2012, 18, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative inhaltsanalyse–ein beispiel für mixed methods. Mix. Meth. Empir. Bild. 2012, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Scells, H.; Zuccon, G.; Koopman, B. Automatic Boolean query refinement for systematic review literature search. In Proceedings of the WWW’19 World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1646–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Scells, H.; Zuccon, G. Generating better queries for systematic reviews. In Proceedings of the 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 8–12 July 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Kusiak, A. Smart manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L.; Kirchhoff, B.A.; Walsh, S.T. Defining the relationship among founding resources, strategies, and performance in technology-intensive new ventures: Evidence from the semiconductor silicon industry. J. Small Bus. Manage. 2007, 45, 438–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, E.; Ciabuschi, F.; Lindahl, O.; Fratocchi, L. A network perspective on the reshoring process: The relevance of the home-and the host-country contexts. Ind. Mark. Manage. 2018, 70, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancarani, A.; Di Mauro, C.; Mascali, F. Backshoring strategy and the adoption of Industry 4.0: Evidence from Europe. J. World Bus. 2019, 54, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Orzes, G.; Sartor, M.; Nassimbeni, G. Reshoring: Does home country matter? J. Purch. Supply Manage. 2019, 25, 100–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.H. It’s not offshoring or reshoring but right-shoring that matters. J. Text. Appar. Technol. Manage. 2016, 10, 112–136. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, P.; Boffelli, A.; Elia, S.; Fratocchi, L.; Kalchschmidt, M.; Samson, D. What can we learn about reshoring after Covid-19? Oper. Manage. Res. 2020, 13, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffelli, A.; Johansson, M. What do we want to know about reshoring? Towards a comprehensive framework based on a meta-synthesis. Oper. Manage. Res. 2020, 13, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benstead, A.V.; Stevenson, M.; Hendry, L.C. Why and how do firms reshore? A contingency-based conceptual framework. Oper. Manage. Res. 2017, 10, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theyel, G.; Hofmann, K.; Gregory, M. Understanding manufacturing location decision making: Rationales for retaining, offshoring, reshoring, and hybrid approaches. Econ. Dev. Q. 2018, 32, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grappi, S.; Romani, S.; Bagozzi, R.P. The effects of reshoring decisions on employees. Pers. Rev. 2019, 49, 1254–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.B.; Steen, M. Make at home or abroad? Manufacturing reshoring through a GPN lens: A Norwegian case study. Geoforum 2020, 113, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanchan, V.; Mulhall, R.; Bryson, J. Repatriation or reshoring of manufacturing to the US and UK: Dynamics and global production networks or from here to there and back again. Growth Change 2018, 49, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanczyk, A.; Cataldo, Z.; Blome, C.; Busse, C. The dark side of global sourcing: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Log. Manage. 2017, 47, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, A. From global to local: Reshoring for sustainability. Oper. Manage. Res. 2016, 9, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wan, L.; Orzes, G.; Sartor, M.; Di Mauro, C.; Nassimbeni, G. Entry modes in reshoring strategies: An empirical analysis. J. Purch. Sup. Manage. 2019, 25, 100522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, P.L.; Ogden, J.A.; Wirthlin, J.R.; Hazen, B.T. Nearshoring, reshoring, and insourcing: Moving beyond the total cost of ownership conversation. Bus. Horizons 2017, 60, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenz, A.; Prettner, K.; Strulik, H. Robots, reshoring, and the lot of low-skilled workers. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 12, 103–744. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.E.; Rothenberg, L.; Moser, H. Contingency factors and reshoring drivers in the textile and apparel industry. J. Manuf. Technol. Manage. 2021, 29, 1025–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R. Reshoring of US apparel manufacturing: Lesson from an innovative North Carolina based manufacturing company. J. Text. Appar. Technol. Manage. 2018, 10, 114–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hilletofth, P.; Sequeira, M.; Adlemo, A. Three novel fuzzy logic concepts applied to reshoring decision-making. Exp. Syst. Appl. 2019, 126, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinkel, S. Future and impact of backshoring—Some conclusions from 15 years of research on German practices. J. Purch. Supply Manage. 2014, 20, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertoni, F.; Elia, S.; Massini, S.; Piscitello, L. The reshoring of business services: Reaction to failure or persistent strategy? J. World Bus. 2017, 52, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancarani, A.; Di Mauro, C.; Fratocchi, L.; Orzes, G.; Sartor, M. Prior to reshoring: A duration analysis of foreign manufacturing ventures. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 169, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grappi, S.; Romani, S.; Bagozzi, R.P. Consumer stakeholder responses to reshoring strategies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciabuschi, F.; Lindahl, O.; Barbieri, P.; Fratocchi, L. Manufacturing reshoring. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 3, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, C.M.; de Lucas, F.M. Reshoring the Spanish production of footwear: Its importance and determinants. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2019, 35, 777–800. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Mora, C.; Merino, F. Consequences of sustainable innovations on the reshoring drivers’ framework. J. Manuf. Technol. Manage. 2020, 31, 1373–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, G.; Sollander, K.; Hilletofth, P.; Eriksson, D. Reshoring drivers and barriers in the Swedish manufacturing industry. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2018, 11, 174–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johansson, M.; Olhager, J.; Heikkilä, J.; Stentoft, J. Offshoring versus backshoring: Empirically derived bundles of relocation drivers, and their relationship with benefits. J. Purch. Supply Manage. 2019, 25, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentoft, J.; Mikkelsen, O.S.; Jensen, J.K.; Rajkumar, C. Performance outcomes of offshoring, backshoring and staying at home manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 199, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, G.R.; Welch, L.S. De-internationalization. MIR Manage. Int. Rev. 1997, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Belderbos, R. Antidumping and foreign divestment: Japanese electronics multinationals in the EU. Rev. World Econ. 2003, 139, 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcan, R.V. The philosophy of turning points: A case of de-internationalization. In Philosophy of Science and Meta-Knowledge in International Business and Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Foerstl, K.; Kirchoff, J.F.; Bals, L. Reshoring and insourcing: Drivers and future research directions. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Log. Manage. 2016, 46, 492–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, P.K.; Hsieh, L. Reshoring: A strategic renewal of luxury clothing supply chains. Oper. Manage. Res. 2016, 9, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strange, R.; Zucchella, A. Industry 4.0, global value chains and international business. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2017, 25, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Wang, Y.; Czinkota, M. Reshoring and sustainable development goals. Brit. J. Manage. 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bals, L.; Kirchoff, J.F.; Foerstl, K. Exploring the reshoring and insourcing decision making process: Toward an agenda for future research. Op. Manage. Res. 2016, 9, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fratocchi, L. Additive manufacturing technologies as a reshoring enabler: A why, where and how approach. World Rev. Interm. Transp. Res. 2018, 7, 264–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratocchi, L.; Di Stefano, C.D. Manufacturing reshoring in the fashion industry: A literature review. World Rev. Interm. Transp. Res. 2019, 8, 338–365. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, W.; Sun, S.; Zhang, G. Reshoring of American manufacturing companies from China. Oper. Manage. Res. 2016, 9, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilletofth, P.; Sequeira, M.; Tate, W. Fuzzy-logic-based support tools for initial screening of manufacturing reshoring decisions. Ind. Manage. Data Syst. 2021, 121, 965–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Barnes, L. Country of origin: Reshoring implication in the context of the UK fashion industry. In Reshoring of Manufacturing; Vecchi, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Mugurusi, G.; de Boer, L. Conceptualising the production offshoring organisation using the viable systems model (VSM). Strateg. Outsourc. Int. J. 2014, 7, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Dotzauer, V.; Voigt, K.I. Industry 4.0 and its impact on reshoring decisions of German manufacturing enterprises. Supply Manage. Res. 2017, 1, 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Chernova, V.Y. Reshoring to the EU and the USA: Problems, trends and prospects. RUDN J. Econ. 2020, 28, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffelli, A.; Fratocchi, L.; Kalchschmidt, M. Doing the right thing or doing things right: What is better for a successful manufacturing reshoring? Oper. Manage. Res. 2021, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancarani, A.; Mauro, C.D.; Virtanen, Y.; You, W. From China to the west: Why manufacturing locates in developed countries. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 1435–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterberger, P.; Müller, J.M. Clustering and classification of manufacturing enterprises regarding their industry 4.0 reshoring incentives. Proc. Comp. Sci. 2021, 180, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Govindan, K.; Mangla, S.K. Structural model for sustainable consumption and production adoption—A grey-DEMATEL based approach. Res. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 125, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uluskan, M.; Godfrey, A.B.; Joines, J.A. Impact of competitive strategy and cost-focus on global supplier switching (reshore and relocation) decisions. J. Text. Inst. 2017, 108, 1308–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.; Govindan, K.; Gold, S. Multi-tier sustainable global supplier selection using a fuzzy AHP-VIKOR based approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 195, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| N. | Key Words and Strings |

|---|---|

| 1 | “reshoring” AND “sustainability” AND “innovation” |

| 2 | “sustainable reshoring” |

| 3 | “innovative/innovation reshoring” |

| 4 | “reshoring” AND “sustainable development” |

| 5 | reshoring” AND “sustainability” AND “digital innovation” |

| 6 | “digital innovation for reshoring sustainability” |

| Delimitation Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Time | Paper published up to the first trimester of 2021 |

| Search area | Title, abstract, keywords |

| Document | Scientific papers |

| Source | Peer-reviewed journals |

| Language | English |

| N. | Title 2 | Scholar | Science Direct | Scopus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “reshoring” AND “sustainability” AND “innovation” | 118 (64) | 100 (79) | 123 (62) |

| 2 | “sustainable reshoring” | 7 (3) | 5 (3) | 55 (30) |

| 3 | “innovation reshoring” | 9 (2) | 1 | 60 (33) |

| 4 | “reshoring” AND “sustainable development” | 104 (19) | 27 (21) | 15 (64) |

| 5 | “reshoring” AND “digital innovation” | 36 (6) | 5 (3) | 92 (65) |

| 6 | “reshoring” AND “sustainability” AND “digital innovation” | 10 (2) | 4 (2) | 30 (23) |

| 7 | “digital innovation reshoring” | 35 (4) | 5 (3) | 45 (21) |

| total after selection based on the three criteria | 300 (100) | 147 (112) | 540 (298) |

| Journal | Num. of Papers |

|---|---|

| Operations Management Research | 8 |

| Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management | 8 |

| Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing | 4 |

| Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management | 3 |

| International Journal of Production Economics | 3 |

| Journal of Supply Chain Management | 2 |

| International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management | 2 |

| Journal of Textile and Apparel, Technology and Management | 2 |

| Journal of World Business | 2 |

| Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | 1 |

| Multinational Business Review | 1 |

| The Journal of the Textile Institute | 1 |

| Resources, Conservation and Recycling | 1 |

| Supply management research | 1 |

| Studies of Applied Economics | 1 |

| RUDN Journal of Economics | 1 |

| Procedia Computer Science | 1 |

| Management International Review | 1 |

| Journal of Production Research | 1 |

| Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal | 1 |

| International Journal of Production Research | 1 |

| International Journal of Management and Economics | 1 |

| IEEE Engineering Management Review | 1 |

| Growth and Change | 1 |

| Geoforum | 1 |

| Expert systems with applications | 1 |

| European Economic Review | 1 |

| European Business Review | 1 |

| Economic Development Quarterly | 1 |

| Business Horizons | 1 |

| British Journal of Management | 1 |

| Decision Motivations | Innovation Drivers | Locations | Sectors | SDGs | Papers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A response to internal changes | Innovative digital technologies (e.g., the Internet of Things, real-time data collection, predictive analytics, big data analytics, blockchain technologies, cloud manufacturing, robotics, artificial or augmented intelligence). | North America and EU countries | Mechanical, tech industry, electronics. | 8. Industry innovation and infrastructures; 9. Decent work and economic growth. | Ancarani et al., 2020, 2021; Belderbos, 2003; Barbieri et al., 2018; Benstead, et al., 2017; Boffelli et al., 2020, 2021; Ciabuschi et al., 2019; Chernova, 2020; Di Mauro et al., 2018; Engström et al., 2018; Fratocchi et al., 2013, 2019a; Grappi et al., 2015, 2019; Gupta et al., 2021; Hartman et al., 2017; Kinkel, 2014; Krenz et al., 2021; Lund et al., 2020; Luthra et al., 2021; Mora, et al., 2019; Mugurusi et al., 2014; Müller et al., 2017; Stentoft et al., 2018; Strange et al., 2017; Tate, 2014; Theyel, et al., 2018; Vanchan et al., 2018; Uluskam et al., 2017; Wan et al., 2019; Zhai et al., 2016. |

| A response to external changes | Innovative digital technologies (the Internet of Things, real-time data collection, predictive analytics, big data analytics, blockchain technologies, cloud manufacturing, robotics, artificial or augmented intelligence).Green innovations (e.g., green and biofuels, biomaterials, green vehicles and machines, green boilers, solar energy conversion technologies, smart containers, automated food waste tracking systems and automated optical scanning technologies, membrane filtration, microbial fuel cells, biological treatments and natural treatment systems, etc.). | North America and EU countries | Fashion, mechanical, furniture, furnishing, pharmaceuticals | 8. Industry innovation and infrastructures; 9. Decent work and economic growth; 12. Responsible consumption and production. | Ashby, 2016; Ancarani et al., 2015, 2020, 2021; Barbieri et al., 2018, 2020; Benstead, et al., 2017; Boffelli et al., 2020, 2021; Ciabuschi et al., 2019; Chernova, 2020; Di Mauro et al., 2018; Engström et al., 2018; Fratocchi et al., 2013, 2019a,b; Grappi et al., 2015; Gupta et al., 2021; Hasan, 2018; Kinkel, 2014; Krenz et al., 2021; Lund et al., 2020; Luthra et al., 2021; Martínez-Mora, Merino, 2020; Moore et al., 2018, 2021; Müller et al., 2017; Orzes, Sarkis, 2019; Robinson et al., 2016; Sarkis, 2019; Stentoft et al., 2018; Strange et al., 2017; Tate, 2014; Theyel, et al., 2018; Unterberger et al., 2021; Vanchan et al., 2018; Uluskam et al., 2017; Wan et al., 2019; Zhai et al., 2016. |

| Correction of prior decisions or actions | Innovative digital technologies (the Internet of Things, real-time data collection, predictive analytics, big data analytics, blockchain technologies, cloud manufacturing, robotics, artificial or augmented intelligence).Green innovations (e.g., green and biofuels, biomaterials, green vehicles and machines, green boilers, solar energy conversion technologies, smart containers, automated food waste tracking systems and automated optical scanning technologies, membrane filtration, microbial fuel cells, biological treatments and natural treatment systems, etc.). | North America and EU countries | Fashion, mechanical, furniture, furnishing, pharmaceuticals. | 8. Industry innovation and infrastructures; 9. Decent work and economic growth; 12. Responsible consumption and production. | Abbasi, 2016; Albertoni et al., 2017; Ancarani et al., 2015, 2020, 2021; Ashby, 2016; Barbieri et al., 2018; Benstead, et al., 2017; Boffelli et al., 2020, 2021; Ciabuschi et al., 2019; Chernova, 2020; Engström et al., 2018; Fratocchi et al., 2013, 2019a,b; Grappi et al., 2015; Gupta et al., 2021; Hasan, 2018; Krenz et al., 2021; Lund et al., 2020; Martínez-Mora, Merino, 2020; Moore et al., 2018, 2021; Müller et al., 2017; Orzes, Sarkis, 2019; Stentoft et al., 2018; Strange et al., 2017; Tate, 2014; Theyel, et al., 2018; Unterberger et al., 2021; Vanchan et al., 2018; Uluskam et al., 2017; Wan et al., 2019; Zhai et al., 2016. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cosimato, S.; Vona, R. Digital Innovation for the Sustainability of Reshoring Strategies: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147601

Cosimato S, Vona R. Digital Innovation for the Sustainability of Reshoring Strategies: A Literature Review. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147601

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosimato, Silvia, and Roberto Vona. 2021. "Digital Innovation for the Sustainability of Reshoring Strategies: A Literature Review" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147601