Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tourism Industry: Applying TRIZ and DEMATEL to Construct a Decision-Making Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Hospitality Industry and the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.2. The Transportation Industry and the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.3. COVID-19 Severely Hit the Travel and Tourism Industry

2.4. Government and the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.5. Tourism Stakeholders and the COVID-19 Pandemic

3. Methods

3.1. TRIZ Principle

3.2. DEMATEL Method

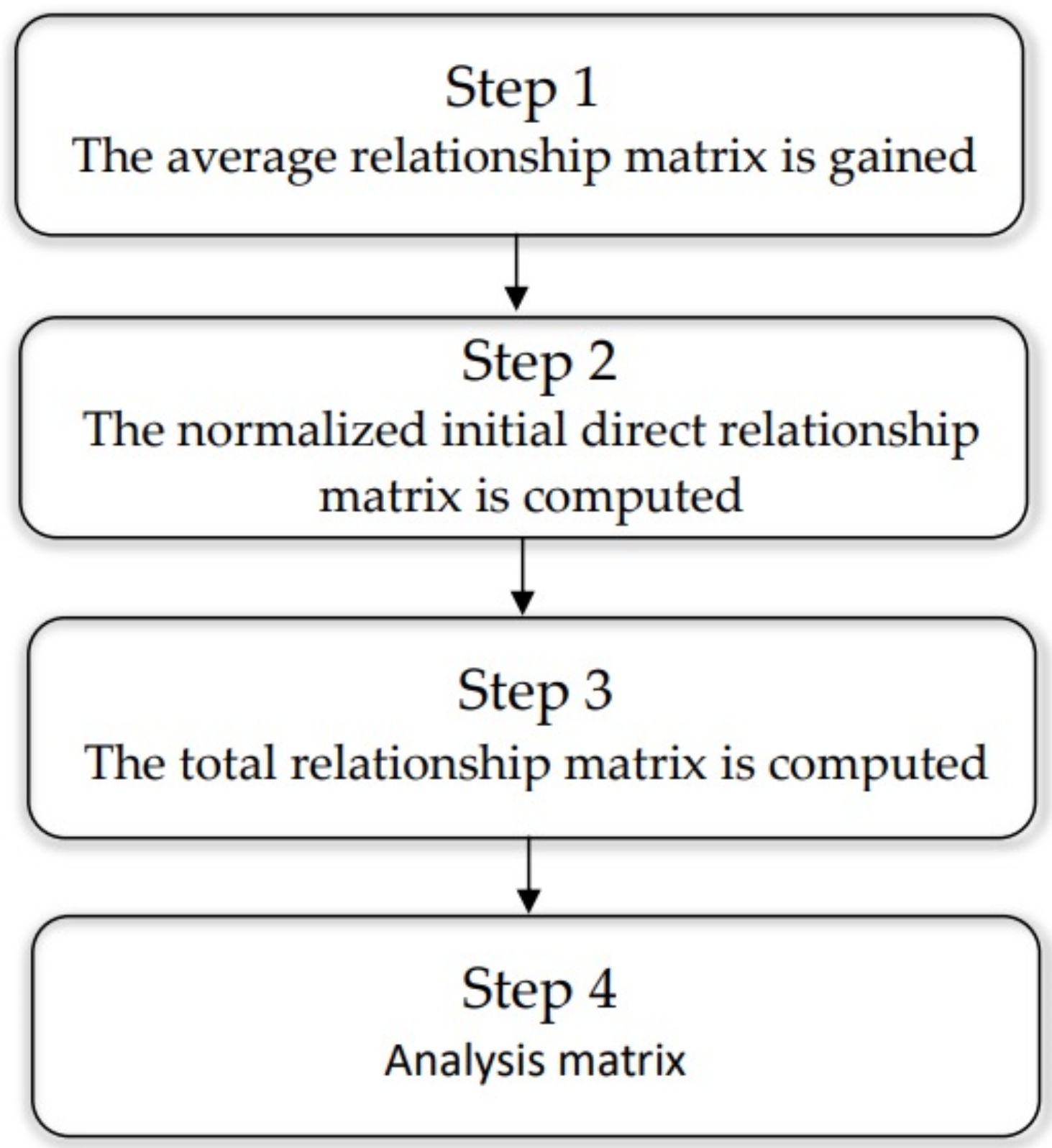

- Step 1.

- The average relationship matrix is gained.

- Step 2.

- The normalized initial direct relationship matrix is computed.

- Step 3.

- The total relationship matrix is computed.

- Step 4.

- Analysis matrix.

4. Evaluating the Innovative Principles of the GMTS

4.1. Possible Contradictions of GMTS

- A.

- The government prohibits the tourism industry under COVID-19, and the international travel contradictions are as follows:

- The government is worried about the spread of the virus due to the flow of tourists increasing the risk of spreading the virus, so the government closes the borders to prevent the spread.

- Travel requires tourists to go to the destination to be completed, and international travel of tourists must use transportation to reach the destination to complete the tour.

- B.

- The contradiction between the transportation industry due to space constraints and the inability of air to flow effectively is as follows:

- The capacity of tourist transportation is limited. Given the limited space of airplanes and cruise ships, the air cannot flow effectively of infection.

- The cost of travel cannot be based on quantity. Therefore, increasing the space of tourists in a limited space will greatly increase the cost.

- C.

- Travel companies need to regulate the risk of travel infections, and tourists are worried about international travel:

- Travel company regulations increase travel costs, and travel regulations must have pandemic prevention equipment, such as masks.

- Tourists are unwilling to increase travel costs; after various costs have increased, tourists will reduce their willingness to travel internationally.

- D.

- Droplet infection between people in tourist hotel rooms at close range:

- The operation of tourist hotels increases costs, and hotels cannot effectively maintain social distance due to close contact, easily spreading the virus.

- Travel cannot be effectively controlled; the number of guest rooms in a hotel is limited. If it is divided into several hotels, the travel company cannot control it.

- E.

- In the international pandemic outbreak, therefore, the government closed the borders and transportation vehicles could not operate effectively internationally:

- The government has closed the borders due to the pandemic, barring tourists from international travel and preventing tourists from causing the risk of infectious diseases.

- The transportation means cannot operate without tourists, causing transportation to stop operating and causing dilemmas.

- F.

- In the safety structure of the hotel industry, improving the space under the pandemic is not easy, and the lack of improvement in the space distance will cause a high risk of infection:

- The hotel industry cannot easily and effectively improve the space because of safety regulations and the construction of the structure under the government regulations.

- There is a high risk of infection caused by the hotel’s space and distance; tourism must be improved to stay safe.

4.2. Application of TRIZ Reasoning Innovation Principles

- Contradiction Relationship (A): between governments and travel companies—mobility; The infectious virus and tourist arrive at the destination to complete the tour.

- Contradiction Relationship (B): between the transportation industry and tourists—capacity is limited and cost cannot be based on quantity.

- Contradiction Relationship (C): between travel companies and tourists—the travel company regulates the increase in travel costs, and the tourists are unwilling to increase travel expenditures.

- Contradiction Relationship (D): between travel companies and the hospitality industry —the increased cost of tourist hotel operation and the ineffective control of the travel company.

- Contradiction Relationship (E): between the government and the transportation industry—in the international pandemic outbreak, the government closed the borders, and transportation vehicles could not operate effectively internationally.

- Contradiction Relationship (F): between tourists and the hotel industry—the safety structure of the hotel industry introduces difficulties in improving the space during the pandemic, and the lack of improvement in the space distance will cause a high risk of infection.

4.3. Evaluating DEMATEL Innovation Principles

- Step 1.

- DEMATEL expert questionnaire design and proposition

- Step 2.

- Questionnaire survey of tourism stakeholders and experts

- Step 3.

- Compute and analyze DEMATEL

- Step 4.

- DEMATEL causal diagram analysis results

5. Results

5.1. General Analysis of DEMATEL

5.2. Causal Diagram

5.3. Cause Group Analysis of the Criteria Factors

5.4. Effect Group Analysis of the Criteria Factors

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications for Research

6.2. Implications for Practice

7. Conclusions and Contribution

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Contribution

8. Limitations and Future Research

8.1. Limitations

8.2. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | F1 | F2 | F3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.306 | 0.353 | 0.341 | 0.305 | 0.314 | 0.317 | 0.334 | 0.355 | 0.343 | 0.345 | 0.341 | 0.315 | 0.345 | 0.320 | 0.334 | 0.296 | 0.300 | 0.260 | 0.297 | 0.311 | 0.274 | 0.287 |

| A2 | 0.382 | 0.325 | 0.372 | 0.331 | 0.338 | 0.335 | 0.356 | 0.376 | 0.366 | 0.368 | 0.363 | 0.333 | 0.368 | 0.340 | 0.357 | 0.329 | 0.330 | 0.288 | 0.324 | 0.340 | 0.300 | 0.309 |

| A3 | 0.344 | 0.340 | 0.289 | 0.296 | 0.306 | 0.307 | 0.323 | 0.338 | 0.331 | 0.332 | 0.325 | 0.308 | 0.341 | 0.311 | 0.325 | 0.295 | 0.294 | 0.256 | 0.293 | 0.306 | 0.270 | 0.281 |

| A4 | 0.376 | 0.376 | 0.367 | 0.284 | 0.338 | 0.340 | 0.355 | 0.373 | 0.362 | 0.362 | 0.363 | 0.339 | 0.373 | 0.338 | 0.354 | 0.331 | 0.327 | 0.289 | 0.324 | 0.337 | 0.296 | 0.309 |

| B1 | 0.314 | 0.309 | 0.299 | 0.272 | 0.243 | 0.281 | 0.298 | 0.312 | 0.305 | 0.303 | 0.298 | 0.284 | 0.309 | 0.284 | 0.290 | 0.269 | 0.273 | 0.236 | 0.271 | 0.274 | 0.239 | 0.253 |

| B2 | 0.331 | 0.327 | 0.320 | 0.284 | 0.297 | 0.256 | 0.315 | 0.327 | 0.319 | 0.317 | 0.314 | 0.292 | 0.327 | 0.295 | 0.311 | 0.288 | 0.290 | 0.253 | 0.285 | 0.291 | 0.253 | 0.267 |

| B3 | 0.334 | 0.326 | 0.323 | 0.284 | 0.295 | 0.295 | 0.269 | 0.327 | 0.312 | 0.314 | 0.309 | 0.291 | 0.328 | 0.291 | 0.308 | 0.286 | 0.290 | 0.249 | 0.287 | 0.292 | 0.254 | 0.267 |

| B4 | 0.354 | 0.349 | 0.345 | 0.303 | 0.318 | 0.317 | 0.326 | 0.301 | 0.338 | 0.335 | 0.333 | 0.308 | 0.345 | 0.312 | 0.329 | 0.299 | 0.304 | 0.263 | 0.299 | 0.309 | 0.266 | 0.283 |

| C1 | 0.361 | 0.352 | 0.349 | 0.311 | 0.323 | 0.320 | 0.339 | 0.357 | 0.299 | 0.346 | 0.341 | 0.315 | 0.348 | 0.319 | 0.333 | 0.311 | 0.303 | 0.266 | 0.302 | 0.318 | 0.277 | 0.291 |

| C2 | 0.344 | 0.338 | 0.337 | 0.300 | 0.310 | 0.304 | 0.324 | 0.343 | 0.340 | 0.289 | 0.334 | 0.309 | 0.345 | 0.315 | 0.322 | 0.300 | 0.296 | 0.256 | 0.290 | 0.308 | 0.266 | 0.281 |

| C3 | 0.341 | 0.331 | 0.329 | 0.298 | 0.306 | 0.306 | 0.322 | 0.346 | 0.339 | 0.332 | 0.284 | 0.301 | 0.339 | 0.311 | 0.322 | 0.297 | 0.293 | 0.259 | 0.293 | 0.302 | 0.269 | 0.280 |

| C4 | 0.318 | 0.315 | 0.309 | 0.268 | 0.279 | 0.280 | 0.292 | 0.310 | 0.304 | 0.301 | 0.296 | 0.242 | 0.310 | 0.282 | 0.293 | 0.269 | 0.269 | 0.236 | 0.268 | 0.283 | 0.246 | 0.258 |

| D1 | 0.329 | 0.327 | 0.320 | 0.280 | 0.292 | 0.293 | 0.310 | 0.326 | 0.312 | 0.315 | 0.312 | 0.289 | 0.282 | 0.292 | 0.307 | 0.290 | 0.283 | 0.246 | 0.279 | 0.296 | 0.257 | 0.271 |

| D2 | 0.323 | 0.320 | 0.315 | 0.282 | 0.285 | 0.283 | 0.298 | 0.317 | 0.312 | 0.310 | 0.312 | 0.288 | 0.317 | 0.250 | 0.299 | 0.275 | 0.275 | 0.242 | 0.274 | 0.283 | 0.252 | 0.264 |

| D3 | 0.327 | 0.320 | 0.316 | 0.283 | 0.291 | 0.291 | 0.305 | 0.325 | 0.319 | 0.323 | 0.321 | 0.292 | 0.330 | 0.296 | 0.267 | 0.289 | 0.281 | 0.243 | 0.273 | 0.294 | 0.261 | 0.273 |

| D4 | 0.251 | 0.251 | 0.244 | 0.221 | 0.222 | 0.226 | 0.237 | 0.251 | 0.245 | 0.247 | 0.240 | 0.227 | 0.257 | 0.227 | 0.239 | 0.193 | 0.220 | 0.187 | 0.212 | 0.232 | 0.204 | 0.214 |

| E1 | 0.320 | 0.319 | 0.314 | 0.280 | 0.295 | 0.295 | 0.309 | 0.325 | 0.316 | 0.315 | 0.310 | 0.289 | 0.319 | 0.287 | 0.306 | 0.282 | 0.244 | 0.247 | 0.286 | 0.284 | 0.250 | 0.264 |

| E2 | 0.305 | 0.305 | 0.297 | 0.262 | 0.278 | 0.280 | 0.297 | 0.307 | 0.297 | 0.298 | 0.295 | 0.272 | 0.305 | 0.275 | 0.291 | 0.267 | 0.273 | 0.202 | 0.270 | 0.273 | 0.243 | 0.253 |

| E3 | 0.307 | 0.307 | 0.297 | 0.268 | 0.283 | 0.282 | 0.296 | 0.309 | 0.298 | 0.294 | 0.290 | 0.276 | 0.302 | 0.271 | 0.287 | 0.265 | 0.273 | 0.237 | 0.230 | 0.273 | 0.240 | 0.253 |

| F1 | 0.325 | 0.321 | 0.316 | 0.281 | 0.285 | 0.283 | 0.303 | 0.320 | 0.312 | 0.309 | 0.306 | 0.289 | 0.328 | 0.291 | 0.307 | 0.288 | 0.277 | 0.246 | 0.276 | 0.251 | 0.257 | 0.274 |

| F2 | 0.298 | 0.299 | 0.293 | 0.258 | 0.271 | 0.271 | 0.289 | 0.301 | 0.290 | 0.289 | 0.288 | 0.269 | 0.306 | 0.273 | 0.284 | 0.263 | 0.262 | 0.233 | 0.261 | 0.275 | 0.206 | 0.258 |

| F3 | 0.322 | 0.320 | 0.315 | 0.277 | 0.285 | 0.285 | 0.302 | 0.319 | 0.311 | 0.307 | 0.307 | 0.286 | 0.322 | 0.291 | 0.304 | 0.285 | 0.277 | 0.247 | 0.279 | 0.296 | 0.262 | 0.231 |

References

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). UNWTO International Tourism Highlights 2019 Edition; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2019; ISBN 9789284421145. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). UNWTO International Tourism Highlights 2020 Edition; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2021; ISBN 9789284422449. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Bureau (MOTC). Statistics of Tourism Revenue and Expenditure from 106 to 108 Years. 2020. Available online: https://admin.taiwan.net.tw/Handlers/FileHandler.ashx?fid=cc3a895c-9289-44b1-b43c-16e63c464283&type=4&no=1 (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Worldometer. Taiwan Population (live). Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/taiwan-population/ (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- UNWTO. COVID-19 and Tourism 2020: A Year in Review. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-12/2020_Year_in_Review_0.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Iaquinto, B.L. Tourist as vector: Viral mobilities of COVID-19. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Burgess, L.G.; Jones, A.; Ritchie, B.W. ‘No Ebola…still doomed’—The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Som, A.P.M.; Wang, J. Organizational Learning in Tourism Crisis Management: An Experience from Malaysia. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller, M. Reconstructing tourism in the Caribbean: Connecting pandemic recovery, climate resilience and sustainable tourism through mobility justice. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1436–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Luo, M.; Huo, T.; Zhao, Q. What is the policy focus for tourism recovery after the outbreak of COVID-19? A co-word analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.X.; Wong, I.A. The social crisis aftermath: Tourist well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 859–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A. COVID-19, indigenous peoples and tourism: A view from New Zealand. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Yoon, H.H. COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, L.K. International Tourism and its Global Public Health Consequences. J. Travel. Res. 2003, 41, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsionas, M.G. COVID-19 and gradual adjustment in the tourism, hospitality, and related industries. Tour. Econ. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, I.; Gunter, U. Blockchain: Is it the future for the tourism and hospitality industry? Tour. Econ. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvani, A.; Lew, A.A.; Perez, M.S. COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-L.; McAleer, M.; Ramos, V. A Charter for Sustainable Tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Gustafsson, A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikarwar, E. Time-varying foreign currency risk of world tourism industry: Effects of COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Ducruet, C. Globalization and Regionalization: Empirical Evidence from Itinerary Structure and Port Organization of World Cruise of Cunard. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radic, A.; Law, R.; Lück, M.; Kang, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.; Han, H. Apocalypse Now or Overreaction to Coronavirus: The Global Cruise Tourism Industry Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.L.; Cardoso, L.; Araújo-Vila, N.; Fraiz-Brea, J.A. Sustainability Perceptions in Tourism and Hospitality: A Mixed-Method Bibliometric Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Cai, M.; Connor, T.; Chung, M.; Liu, J. Metacoupled Tourism and Wildlife Translocations Affect Synergies and Trade-Offs among Sustainable Development Goals across Spillover Systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Sousa, A.; Prados, J.P. Visitor Management in World Heritage Destinations before and after Covid-19, Angkor. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N.; Bakas, F.; de Castro, T.; Silva, S. Creative Tourism Development Models towards Sustainable and Regenerative Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A.; Palrão, T.; Mendes, A. The Impact of Pandemic Crisis on the Restaurant Business. Sustainability 2020, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Shu, F.; Kitterlin-Lynch, M.; Beckman, E. Perceptions of cruise travel during the COVID-19 pandemic: Market recovery strategies for cruise businesses in North America. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Teba, E.; García-Mestanza, J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, M. The Application of the Inbound Marketing Strategy on Costa del Sol Planning & Tourism Board. Lessons for Post-COVID-19 Revival. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varelas, S.; Apostolopoulos, N. The Implementation of Strategic Management in Greek Hospitality Businesses in Times of Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Hong, Y.; Xu, L.; Gao, W.; Wang, K.; Chi, X. An Evaluation of Green Ryokans through a Tourism Accommodation Survey and Customer-Satisfaction-Related CASBEE–IPA after COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-E.; Park, C.; Lee, C.-K.; Lee, S. The Stress-Induced Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism and Hospitality Workers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, D.; Andrinos, M. The Role of Sustainable Restaurant Practices in City Branding: The Case of Athens. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.; Sowamber, V. Corporate Social Responsibility at LUX * Resorts and Hotels: Satisfaction and Loyalty Implications for Employee and Customer Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhammar, H.; Li, W.; Molina, C.; Hickey, V.; Pendry, J.; Narain, U. Framework for Sustainable Recovery of Tourism in Protected Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugalski, Ł. The Undisrupted Growth of the Airbnb Phenomenon between 2014–2020. The Touristification of European Cities before the COVID-19 Outbreak. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pérez, V.; Peña-García, A. The Contribution of Peripheral Large Scientific Infrastructures to Sustainable Development from a Global and Territorial Perspective: The Case of IFMIF-DONES. Sustainability 2021, 13, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gallo, M.; Jiménez-Naharro, F.; Torres-García, M.; Guadix-Martín, J.; Giesecke, S. Sustainability of Spanish Tourism Start-Ups in the Face of an Economic Crisis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, Y.; Karkour, S.; Ichisugi, Y.; Itsubo, N. Evaluation of the Economic, Environmental, and Social Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Japanese Tourism Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, I.; Coscia, C.; Curto, R. Identifying Spatial Relationships between Built Heritage Resources and Short-Term Rentals before the Covid-19 Pandemic: Exploratory Perspectives on Sustainability Issues. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, E.; Tsutsui, Y. The Impact of Postponing 2020 Tokyo Olympics on the Happiness of O-MO-TE-NA-SHI Workers in Tourism: A Consequence of COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Monitoring the impacts of tourism-based social media, risk perception and fear on tourist’s attitude and revisiting behaviour in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.; Sousa, Á.; Santos, C. The Impacts of COVID-19 Crisis over the Tourism Expectations of the Azores Archipelago Residents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Ryu, H. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), Traveler Behaviors, and International Tourism Businesses: Impact of the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Knowledge, Psychological Distress, Attitude, and Ascribed Responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-J.; Kim, J.; Han, S.-H. Understanding Student Acceptance of Online Learning Systems in Higher Education: Application of Social Psychology Theories with Consideration of User Innovativeness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chin, W.; Nechita, F.; Candrea, A. Framing Film-Induced Tourism into a Sustainable Perspective from Romania, Indonesia and Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xue, T.; Wang, T.; Wu, B. The Mechanism of Tourism Risk Perception in Severe Epidemic—the Antecedent Effect of Place Image Depicted in Anti-Epidemic Music Videos and the Moderating Effect of Visiting History. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-J.; Kim, Y. Does VR Tourism Enhance Users’ Experience? Sustainability 2021, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, F.; Tai, S.; Wu, J.; Mu, Y. Study on Glacial Tourism Exploitation in the Dagu Glacier Scenic Spot Based on the AHP–ASEB Method. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, N.; Vrana, V.; Duy, N.; Minh, D.; Dzung, P.; Mondal, S.; Das, S. The Role of Human–Machine Interactive Devices for Post-COVID-19 Innovative Sustainable Tourism in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships: Politics, Practice and Sustainability; Channel View Publications: England, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Rethinking Collaboration and Partnership: A Public Policy Perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 1999, 7, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Assaf, A.G.; Tsionas, M.G. Developing Courageous Research Ideas. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A.; Cheer, J.M.; Haywood, M.; Brouder, P.; Salazar, N.B. Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hystad, P.W.; Keller, P.C. Towards a destination tourism disaster management framework: Long-term lessons from a forest fire disaster. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S. Collaboration and Partnership Development for Sustainable Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2013, 15, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.-S.; Liu, S.-M.; Chen, Y.-C. Applying DEMATEL to assess TRIZ’s inventive principles for resolving contradictions in the long-term care cloud system. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 1244–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, F.; Gok, M.S. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic tourism: A DEMATEL method analysis on quarantine decisions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyitoğlu, F.; Ivanov, S. Service robots as a tool for physical distancing in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1631–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappe, A.; Luhby, T. 22 Million Americans Have Filed for Unemployment Benefits in the Last Four Weeks. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/16/economy/unemployment-benefits-coronavirus/index.html (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Baum, T.; Hai, N.T.T. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T.; Mooney, S.K.; Robinson, R.N.; Solnet, D. COVID-19’s impact on the hospitality workforce—New crisis or amplification of the norm? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2813–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Nicolau, J.L. An open market valuation of the effects of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Derqui, B.; Matute, J. The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AHLA. Report: State of Hotel Industry Six Months into COVID Pandemic. Available online: https://www.ahla.com/press-release/report-state-hotel-industry-six-months-covid-pandemic (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Wu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Law, R.; Zheng, T. Fluctuations in Hong Kong Hotel Industry Room Rates under the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak: Evidence from Big Data on OTA Channels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, L.-P.; Chin, M.-Y.; Tan, K.-L.; Phuah, K.-T. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism industry in Malaysia. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.; Alonso-Almeida, M. COVID-19 Impacts and Recovery Strategies: The Case of the Hospitality Industry in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, F.; Bonanno, G.; Foglia, F. On the choice of accommodation type at the time of Covid-19. Some evidence from the Italian tourism sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davahli, M.R.; Karwowski, W.; Sonmez, S.; Apostolopoulos, Y. The Hospitality Industry in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Current Topics and Research Methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo-Thanh, T.; Vu, T.-V.; Nguyen, N.P.; van Nguyen, D.; Zaman, M.; Chi, H. How does hotel employees’ satisfaction with the organization’s COVID-19 responses affect job insecurity and job performance? J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 907–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Global environmental consequences of tourism. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2002, 12, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Biological Invasion, Biosecurity, Tourism, and Globalization of Handbook of Globalisation and Tourism; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Rayash, A.; Dincer, I. Analysis of mobility trends during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic: Exploring the impacts on global aviation and travel in selected cities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 68, 101693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJAZEERA. Coronavirus: Travel Restrictions, Border Shutdowns by Country. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/coronavirus-travel-restrictions-border-shutdowns-country-200318091505922.html (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Freedman, D.O.; Leder, K. Influenza: Changing Approaches to Prevention and Treatment in Travelers. J. Travel Med. 2006, 12, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Degrowth.info. A Degrowth Perspective on the Coronavirus Crisis. Available online: https://www.degrowth.info/en/2020/03/a-degrowth-perspective-on-the-coronavirus-crisis/#more-473015 (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Luo, J.; Lam, C. Travel Anxiety, Risk Attitude and Travel Intentions towards “Travel Bubble” Destinations in Hong Kong: Effect of the Fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allplane. Updated (31/12/20)—The 2020 Airline Bankruptcy List Now Closed. Available online: https://allplane.tv/blog/2020/1/17/airlines-that-stopped-flying-in-2020 (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- IATA. Slow Recovery Needs Confidence Boosting Measures. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2020-04-21-01/ (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Forsyth, P.; Guiomard, C.; Niemeier, H.-M. Covid-19, the collapse in passenger demand and airport charges. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATAG. Up to Million Jobs at Risk Due to COVID-19 Aviation Downturn. Available online: https://www.atag.org/component/news/?view=pressrelease&id=122 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.; Jęczmyk, A.; Zawadka, J.; Uglis, J. Agritourism in the Era of the Coronavirus (COVID-19): A Rapid Assessment from Poland. Agriculture 2020, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. 2020: Worst Year in Tourism History with 1 Billion Fewer International Arrivals. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/2020-worst-year-in-tourism-history-with-1-billion-fewer-international-arrivals (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.-J. The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020). Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, T.D.; Tran, T.C.; Tran, V.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T. Is Vietnam ready to welcome tourists back? Assessing COVID-19’s economic impact and the Vietnamese tourism industry’s response to the pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishar, A.; Šťastná, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural tourism in Czechia Preliminary considerations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flew, T.; Kirkwood, K. The impact of COVID-19 on cultural tourism: Art, culture and communication in four regional sites of Queensland, Australia. Media Int. Aust. 2021, 178, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C.M.; Baum, T. COVID-19 and African tourism research agendas. Dev. South. Afr. 2020, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.; Parkb, J.; Na Lic, S.; Songb, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzanegan, M.R.; Gholipour, H.F.; Feizi, M.; Nunkoo, R.; Andargoli, A.E. International Tourism and Outbreak of Coronavirus (COVID-19): A Cross-Country Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.; Scuderi, R. COVID-19 and the recovery of the tourism industry. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, L.H.N.; Law, R.; Ye, B.H. Outlook of tourism recovery amid an epidemic: Importance of outbreak control by the government. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, T. Coronavirus is Devastating Chinese Tourism. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/02/economy-coronavirus-myanmar-china-tourism/606715/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X. Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of infectious disease outbreak. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, A.O.J.; Koh, S.G.M. COVID-19 and Extended Reality (XR). Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1935–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.C.; Ong, C.Y. Overview of rapid mitigating strategies in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health 2020, 185, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, T. Analysis of optimal timing of tourism demand recovery policies from natural disaster using the contingent behavior method. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurovic, G.; Djurovic, V.; Bojaj, M.M. The macroeconomic effects of COVID-19 in Montenegro: A Bayesian VARX approach. Financial Innov. 2020, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R. Collaboration and cooperation in a tourism destination: A network science approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denicolai, S.; Cioccarelli, G.; Zucchella, A. Resource-based local development and networked core-competencies for tourism excellence. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zee, E.; Vanneste, D. Tourism networks unravelled; a review of the literature on networks in tourism management studies. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 15, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhati, A.S.; Agarwal, M. Vandalism control: Perception of multi-stakeholder involvement in attraction management. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.; Zhong, L.; Martin, S. Mental health key to tourism infrastructure in China’s new megapark. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, H.-Y.; Chang, S.-T. Resident perceptions and support before and after the 2018 Taichung international Flora exposition. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayemi, L.O.; Boodoosingh, R.; Sam, F.A.-L. Is Samoa Prepared for an Outbreak of COVID-19? Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2020, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornhorst, T.; Ritchie, J.B.; Sheehan, L. Determinants of tourism success for DMOs & destinations: An empirical examination of stakeholders’ perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Gursoy, D. An Examination of Changes in Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts Over Time: The Impact of Residents’ Socio-demographic Characteristics. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 1332–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. An Introduction to TRIZ-the Russian Theory of Inventive Problem Solving; Ideation International Inc.: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 1996; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ilevbare, I.M.; Probert, D.; Phaal, R. A review of TRIZ, and its benefits and challenges in practice. Technovation 2013, 33, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhman, I. TRIZ Technology for Innovation; Cubic Creativity Company: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, M.; Campodall’Orto, S.; Frattini, F.; Vercesi, P. Enabling open innovation in small- and medium-sized enterprises: How to find alternative applications for your technologies. R D Manag. 2010, 40, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeradist, T.; Thawesaengskulthai, N.; Sangsuwan, T. Using TRIZ to enhance passengers’ perceptions of an airline’s image through service quality and safety. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2016, 53, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, A.F.; Naveiro, R.M.; Aoussat, A.; Reyes, T. Systematic literature review of eco-innovation models: Opportunities and recommendations for future research. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 1278–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chechurin, L.; Borgianni, Y. Understanding TRIZ through the review of top cited publications. Comput. Ind. 2016, 82, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Khodaverdi, R.; Vafadarnikjoo, A. Intuitionistic fuzzy based DEMATEL method for developing green practices and performances in a green supply chain. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 7207–7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-H.; Wang, F.-K.; Tzeng, G.-H. The best vendor selection for conducting the recycled material based on a hybrid MCDM model combining DANP with VIKOR. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 66, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-C.; You, J.-X.; Lu, C.; Chen, Y.-Z. Evaluating health-care waste treatment technologies using a hybrid multi-criteria decision making model. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Khodaverdi, R.; Vafadarnikjoo, A. A grey DEMATEL approach to develop third-party logistics provider selection criteria. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 690–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimdel, M.J.; Noferesti, H. Investment preferences of Iran’s mineral extraction sector with a focus on the productivity of the energy consumption, water and labor force. Resour. Policy 2020, 67, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Wang, B.; Song, W. Analyzing the interrelationships among barriers to green procurement in photovoltaic industry: An integrated method. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Kumar, J.A.; Bansal, P. A multicriteria decision making approach to study barriers to the adoption of autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2020, 133, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.-X.; Wu, Z.-X.; Dinçer, H.; Kalkavan, H.; Yüksel, S. Analyzing TRIZ-based strategic priorities of customer expectations for renewable energy investments with interval type-2 fuzzy modeling. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Su, J. A combined fuzzy DEMATEL and TOPSIS approach for estimating participants in knowledge-intensive crowdsourcing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 137, 106085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Samad, S.; Manaf, A.A.; Ahmadi, H.; Rashid, T.; Munshi, A.; Almukadi, W.; Ibrahim, O.; Ahmed, O.H. Factors influencing medical tourism adoption in Malaysia: A DEMATEL-Fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 137, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-W.; Kuo, T.-C.; Chen, S.-H.; Hu, A.H. Using DEMATEL to develop a carbon management model of supplier selection in green supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.T.-W.; Lin, C.-W. The cognition map of financial ratios of shipping companies using DEMATEL and MMDE. Marit. Policy Manag. 2013, 40, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schad, J.; Lewis, M.W.; Raisch, S.; Smith, W.K. Paradox Research in Management Science: Looking Back to Move Forward. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 5–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.-H. Supply chain-based barriers for truck-engine remanufacturing in China. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2014, 68, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontela, E.; Gabus, A. The DEMATEL Observer; Battelle Geneva Research Center: Geneva, Switzerland, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.-J. Using fuzzy DEMATEL to evaluate the green supply chain management practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.W.; Xiong, L.; Lan, W.; Gong, J. Impact of COVID-19: Research note on tourism and hospitality sectors in the epicenter of Wuhan and Hubei Province, China. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3705–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.B. Bubble in, bubble out: Lessons for the COVID-19 recovery and future crises from the Pacific. World Dev. 2020, 135, 105072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N. The coronavirus is here to stay—here’s what that means. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 590, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Issues of the GMTS | Innovative Principles Derived from Heuristic Reasoning for the GMTS |

|---|---|

| The government is worried about the spread of the virus of travel mobility and travel need tourists to go to the destination to complete | (A1) Under different context, the government will update the tourism policy in a timely manner to achieve optimal results (A2) Transforming international travel into domestic has a positive effect. (A3) Replace international travel with the expand on domestic homogeneous travel destinations. (A4) To conclude with more travel “bubble zones” to ensure the safety of pandemic prevention. |

| TRIZ parameters | Innovative principles derived from reasoning for TRIZ |

| Undesired Result (conflict): #15Duration of action of moving object #31 Object-generated harmful factors | #15 Dynamicity, Optimization #22 Convert harm into benefit, Blessing in disguise #33 Homogeneity #31 Use of porous materials |

| Issues of the GMTS | Innovative Principles Derived from Heuristic Reasoning for the GMTS |

|---|---|

| The contradiction between the transportation industry due to space constraints and the inability of air to flow effectively. | (B1) Adjust the space separation distance in transportation vehicles cabins in advance. (B2) Improve the atmosphere circulation system of transportation vehicles cabins. (B3) Change the density of transportation cabins inresponse to the characteristics and number of tourists. (B4) Transport vehicles often use disposable consumables or items that are cleaned and restored to keep the cabins clean, such as alcohol disinfection or items that can mask the respiratory system. |

| TRIZ parameters | Innovative principles derived from reasoning for TRIZ |

| Undesired Result (conflict): #23 Loss of substance #8 Volume of stationary object | #10 Prior action #39 Inert environment or atmosphere #35 parameter change, changing Properties #34 Rejection and regeneration, Discarding andrecovering |

| Issues of the GMTS | Innovative Principles Derived from Heuristic Reasoning for the GMTS |

|---|---|

| The travel companies regulates the increase in travel costs and the tourist travel costs are unwilling to increase expenditures. | (C1) The travel company arranges various travel-related matters such as cabin interior, and must identify the safety of preventing diseases. (C2) Travel companies arranging travel-related matters must identify the operational procedures to eliminate the risk of infection in advance and make them available to tourist inspection. (C3) The travel company should compulsorily obtain a health quarantine certificate for each tourist each time when performing international travel to prevent infectious diseases. (C4) In this COVID-19 pandemic, travel companies can improve the overall quality and value of travel. |

| TRIZ parameters | Innovative principles derived from reasoning for TRIZ |

| Undesired Result (conflict): #35 Adaptability orversatility #36 Device complexity | #35 parameter change, changing Properties #10 Prior action #28. Replacement of a mechanical system with fields #29 Pneumatics or hydraulics |

| Issues of the GMTS | Innovative Principles Derived from Heuristic Reasoning for the GMTS |

|---|---|

| The increased cost of tourist hotel operation and the ineffective control of tourism. | (D1) The volume density of hotel cabins must be adjustedaccording to the characteristics of tourist and the tourist numbers. (D2) Travel companies should establish contact groupsduring each trip to increase contact frequency and effective control. (D3) The hotel industry obtains tourist information andquarantine certificates in advance when administer accommodation business to prevent infectious diseases. (D4) In context of infectious diseases, travel companies and the hotel industry have advanced the concept of a singleprevention room, which reverses the traditional concept of a two-person travel room. |

| TRIZ parameters | Innovative principles derived from reasoning for TRIZ |

| Undesired Result (conflict): #37Difficulty of detecting and measuring #23 Loss of substance | #35parameter change, changing Properties #18 Mechanical vibration/oscillation #10 Prior action #13 Inversion, the other way around |

| Issues of the GMTS | Innovative Principles Derived from Heuristic Reasoning for the GMTS |

|---|---|

| The international pandemic outbreak, therefore, the government closed the borders and the transportation vehicles could not operate effectively internationally. | (E1) Change the structural quality of the transportationsystem and effectively prevent disease infection. (E2) The design of the transportation vehicle cabin was changed, and the space replaced the straight line with the curve, and the curved surface replaced the plane. (E3) Take advantage of the occurrence of the pandemic to quickly change the Overall pandemic prevention structure of transportation vehicles. |

| TRIZ parameters | Innovative principles derived from reasoning for TRIZ |

| Undesired Result (conflict): #11 Stress or pressure #26 Quantity of substance | #3. Local Quality #14. Spheroidality, Curvilinearity #36. Phase transformation #10 Prior action(repeat) |

| Issues of the GMTS | Innovative Principles Derived from Heuristic Reasoning for the GMTS |

|---|---|

| The safety structure of the hotel industry is not easy to improve the space under the pandemic, and the lack of improvement in the space distance will cause high risk of infection. | (F1) Without damage to the structure, it is effectively divided into separate tourist hotel rooms to prevent infection. (F2) Convert harm into benefit. The space saved in the hotel will be added to useful facilities for tourists, such as independent reading rooms. (F3) Change the hotel space to use composite materials to prepare for appropriate adjustments at any time. |

| TRIZ parameters | Innovative principles derived from reasoning for TRIZ |

| Undesired Result (conflict): #6 Area of moving object #31Object-generatedharmful factors | #1 Segmentation #22 Convert harm into benefit #40 Composite materials |

| Stakeholders | No | Experts Organizations/Title | Seniority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot Questionnaire | 1 | National Central University/professor | 35 |

| 2 | Feng Chia University/associate researcher | 26 | |

| Government | 3 | Tourism Bureau, Republic of China (Taiwan)/ deputy director | 17 |

| 4 | Taoyuan City Government/deputy district chief | 15 | |

| Travel Company | 5 | Poa International Travel Agent/general manager | 30 |

| 6 | Hsi Hung Travel Service Co. Ltd./director | 30 | |

| 7 | Grandee Express Crop/chairman | 40 | |

| Transportation Industry | 8 | EVA Airways Corporation/director | 26 |

| 9 | Overseas Travel Service (Airlines & Cruises GSA)/general manager | 20 | |

| 10 | Chinese Maritime Transport Ltd./senior manager | 46 | |

| Hotel (Hospitality) Industry | 11 | Shangri-La’s Far Eastern Plaza Hotel Taipei/ manager | 14 |

| 12 | Le Méridien Taipei/supervisor | 10 | |

| 13 | Sunworld Dynasty Hotel Taipei/manager | 33 | |

| Academic University | 14 | Tungnan University Tourism Department /associate professor | 30 |

| 15 | Ming Chuan University Tourism field /assistant professor | 35 |

| Criteria Factors | ri | cj | ri + cj | ri − cj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 Optimization Policy | 6.994 | 7.212 | 14.207 | −0.218 |

| A2 Conversion Policy | 7.531 | 7.128 | 14.659 | 0.404 |

| A3 Internationalization Strategy | 6.811 | 7.005 | 13.816 | −0.195 |

| A4 Quality Management | 7.514 | 6.228 | 13.742 | 1.287 |

| B1 Distance Control | 6.218 | 6.455 | 12.673 | −0.236 |

| B2 System Management | 6.559 | 6.448 | 13.007 | 0.111 |

| B3 Humanized Management | 6.532 | 6.800 | 13.332 | −0.268 |

| B4 Cleaning Management | 6.936 | 7.164 | 14.100 | −0.228 |

| C1 Tourism Regulations | 7.081 | 6.973 | 14.053 | 0.108 |

| C2 Transparency Strategy | 6.852 | 6.951 | 13.803 | −0.099 |

| C3 Mandatory Policy | 6.800 | 6.884 | 13.684 | −0.084 |

| C4 Upgrade Strategy | 6.230 | 6.414 | 12.644 | −0.184 |

| D1 Space Management | 6.507 | 7.147 | 13.653 | −0.640 |

| D2 Security Control | 6.377 | 13.617 | 19.994 | −7.241 |

| D3 Hotel Regulations | 6.520 | 6.769 | 13.289 | −0.248 |

| D4 Health Management | 5.045 | 6.268 | 11.313 | −1.223 |

| E1 Structure Management | 6.456 | 6.237 | 12.694 | 0.219 |

| E2 Space Design | 6.144 | 5.443 | 11.587 | 0.702 |

| E3 Structure Preparation | 6.140 | 6.174 | 12.314 | −0.035 |

| F1 Guest Room Management | 6.446 | 6.428 | 12.874 | 0.018 |

| F2 Hotel facilities Management | 6.038 | 5.643 | 11.681 | 0.394 |

| F3 Hotel Material Preparation | 6.431 | 5.921 | 12.352 | 0.511 |

| Criteria Factors | ri | cj | ri + cj | ri – cj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 Optimization Policy | 6.994 | 7.212 | 14.207 | −0.218 |

| A2 Conversion Policy | 7.531 | 7.128 | 14.659 | 0.404 |

| A3 Internationalization Strategy | 6.811 | 7.005 | 13.816 | −0.195 |

| A4 Quality Management | 7.514 | 6.228 | 13.742 | 1.287 |

| B3 Humanized Management | 6.532 | 6.800 | 13.332 | −0.268 |

| B4 Cleaning Management | 6.936 | 7.164 | 14.100 | −0.228 |

| C1 Tourism Regulations | 7.081 | 6.973 | 14.053 | 0.108 |

| C2 Transparency Strategy | 6.852 | 6.951 | 13.803 | −0.099 |

| C3 Mandatory Policy | 6.800 | 6.884 | 13.684 | −0.084 |

| D1 Space Management | 6.507 | 7.147 | 13.653 | −0.640 |

| D3 Hotel Regulations | 6.520 | 6.769 | 13.289 | −0.248 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, D.-S.; Wu, W.-D. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tourism Industry: Applying TRIZ and DEMATEL to Construct a Decision-Making Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147610

Chang D-S, Wu W-D. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tourism Industry: Applying TRIZ and DEMATEL to Construct a Decision-Making Model. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147610

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Dong-Shang, and Wei-De Wu. 2021. "Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tourism Industry: Applying TRIZ and DEMATEL to Construct a Decision-Making Model" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147610