Abstract

In the past few years, deciduous landscape conservation has become a trend in China; however, the theoretical support is still limited, and the impact of demographic characteristics on people’s attitude toward deciduous landscape still needs to be explained. This study aimed at exploring the differences among demographic groups through Likert scale questionnaires of 981 respondents. The results show that of all characteristics, only age has a significant influence on deciduous landscape preference. However, there is a paradox for elderly people: they have the highest preference for deciduous landscape and the lowest intention to keep deciduous landscape in their lives at the same time. Moreover, the elderly tend to care about the underlying surface of deciduous landscape while the reliable predictor for other age groups is the color of fallen leaves. These findings can be useful for practical applications, which might guide future development of deciduous landscape planning and maintenance.

1. Introduction

In the urban context, losing daily contact with natural environment causes people’s constant tiredness and anxiety, which might lead to mental illness [1], especially for elderly people who are used to natural environment and children who have limited access to and interest in natural environment nowadays [2,3]. For centuries, humans have tried to transform natural vegetation into tended vegetation, yet comparing to the former, human-controlled vegetation has limited ecological values as well as aesthetical values [4,5]. Recent evidence suggests that natural landscapes are more appreciated and valued than tamed nature; for instance, meadows are generally preferred to formal bedding plants [6,7]. There has been an ecological planning trend to introduce natural vegetation back into urban ecosystems [8,9,10], to create deep connections with the natural world for the benefit of people and to balance the relationship between people and nature [11,12,13], and deciduous landscape is certainly part of it.

Deciduous landscape is a scenery made up of unswept fallen leaves, which creates a precious seasonal view in urban cities [14]. For decades, it seemed that fallen leaves in cities were supposed to be cleaned up immediately to keep the streets neat; however, as people realized the importance of cooperating with energies put into play by nature [15], this natural scenery started to be valued [16]. In 2013, Shanghai Forestry Bureau issued a policy to leave it be and keep this seasonal natural scenery; this policy was responded to well, and several other cities followed, which led to a new “fashion” in China [16,17]. There were many reports about this unique view as well as people’s reactions, most people enjoy having this natural scenery in their lives, but they also had their concerns [18,19]. Previous research has proven that low-maintenance vegetative landscapes tend to receive negative responses from the public [20,21]. Even though deciduous landscape provides people with a rare opportunity to embrace nature, it can also cause problems from the lack of management, which might lead to chaos or even dangers [22], therefore seriously harming people’s needs and preferences [23].

Aesthetic assessment is a process of interactions between the characteristics of landscape and the psychological responses of observers, which means that landscape preference is influenced by landscape itself as well as demographic characteristics of people [24,25,26], such as their gender, age, education level, occupation, living environment, etc. [27,28,29,30]. In other words, even for the same landscape, people’s preferences can be significantly different [31]. For instance, elderly people were found to have relatively low preference for wild natural landscapes [25], when more than half of users of urban parks are elderly people who can be particularly disadvantaged if their specific need, preference or constraints are not considered in the planning process of parks or other kinds of urban landscapes [32,33]. Landscape is a key element of both individual and social well-being, and the public’s wish to enjoy high-quality landscapes needs to be responded to [34]. While exploring the similarities of different people’s preferences helps us to guide the general planning, figuring out the differences among them allows us to sort out conditions of specific groups such as the elderly so that their needs would be met [35].

Deciduous landscape has its benefits and drawbacks, which are likely to cause divided opinions. The authors’ previous research showed that people are generally more attracted to deciduous landscape if there is a large quantity of light yellow leaves falling over lawn and it goes with rest facilities [14]. However, studies of deciduous landscape are still limited, and the existing studies fail to resolve the contradiction among different people’s preference of deciduous landscape. Thus, this paper attempts to investigate the following questions: (1) Which demographic characteristics have significant effects on people’s preference for deciduous landscape? (2) What kinds of deciduous landscapes are the most and least appreciated? Which deciduous landscape characteristics have dominant influence on the preference of different groups?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

Xi’an is a city located in the middle of Shaanxi Province, northwestern China, situated on the borderline between semi-arid and humid subtropical climate zones [36]. It covers an area of 10,752 square kilometers and has a population of 10.2 million [37]. Xi’an is influenced by the continental monsoon climate and has four distinct seasons with hot, humid summers and cold, dry winters. From 2009 to 2018, the monthly mean maximum temperature was 28.07 °C in July and the monthly mean minimum temperature was 0.49 °C in January [38], which created the temperature difference that helps fall-colored leaves to be extra colorful.

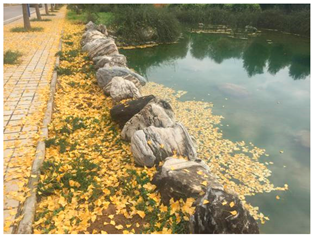

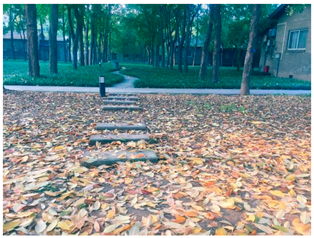

The study was conducted at the campus of Northwest A&F University in Xi’an (108°5′18″ E, 34°15′44″ N), where the pictures were taken and the on-site questionnaires were handed out. Northwest A&F University has various deciduous trees with a greening ratio of 66% [39], and in the past few falls, the deciduous landscape there has been kept, which makes the campus a suitable place for our study.

2.2. Questionnaire Design

To test people’s preferences on deciduous landscape, this study used photos as replaced stimuli of the real scenery, which is both easier for researchers to control and for respondents to understand the content and has been widely used in previous landscape preference studies [8,40]. There were 40 photos in the questionnaire, which were selected from over 200 photos taken on the campus of Northwest A&F University by R.F. in 2017, from September to November. These photos represented different color, amount and shape of the leaves and different planting pattern, underlying surface, collocation, weather, background, etc. (Appendix A).

The questionnaire consisted of three parts. Part A: General questions about the respondents, including their gender, age, educational level and occupation classified by Holland vocational interest theory [41]. Part B: Evaluation of the 40 photos. A five-point Likert scale (1 = “really don’t like” to 5 = “really like”) was used, and the respondents were encouraged to use the whole scale to express how much they like the scenery in each picture. Part C: Deciduous-landscape-related questions, for instance, how much time or money the respondents were willing to spend to visit deciduous landscape, which factor they valued the most, etc. (Appendix A).

2.3. Survey

In 2018, the survey was performed both online and on-site. The online part of the questionnaires was given out with color photographs in July and collected for a week, and the on-site questionnaires were color-printed on A4 papers and given out on the campus, on two weekends in November. We invited random volunteers to do the questionnaires in deciduous landscape streets, with bookmarks made of leaves as presents. Only questionnaires with all the questions answered as required can be counted as valid questionnaires and used for further analysis. The on-site survey included 400 respondents, from which 356 respondents answered all the questions as required, while the online survey included 625 respondents, and all of them met the standard because of the preset rules, which provided us with 981 valid questionnaires in total (Table 1).

Table 1.

Major demographic characteristics (age, education level, gender, occupation) profile of survey respondents.

2.4. Landscape Characteristics Judgment

The color and amount of leaves, planting pattern, underlying surface and other elements such as water features, seats and bush were proved to be the deciduous landscape characteristics that have significant effects on people’s preference [14]. After the survey, the above characteristics in 40 photos were measured in specific scales (Table 2) in order to investigate the relationship between these characteristics and the score of deciduous landscape preference from different demographic groups.

Table 2.

Major evaluation indicators and scoring of deciduous landscape.

2.5. Data Analysis

To evaluate and compare the preferences of respondents, SPSS 19.0 software was used to perform the following analyses. Even though the Likert response data showed non-normal distribution, the sample sizes were large enough to make statistical analysis robust, and the non-parametric techniques were used [6]. The reliability of the questionnaire was tested by the Cronbach’s alpha test. The Spearman’s rank correlation analysis and the Jonckheere–Terpstra test were used to find out which characteristics of the respondents can be reliable predictors for the preference of deciduous landscape. A linear regression analysis was used to test reliable predictors for different demographic groups. The above analysis methods were widely used in previous works [35,42,43].

3. Results

3.1. Overall Evaluation of the Deciduous Landscape Photographs

The reliability of preference scores of the 40 photographs used in the questionnaire was tested. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.965, which means the results have high reliability.

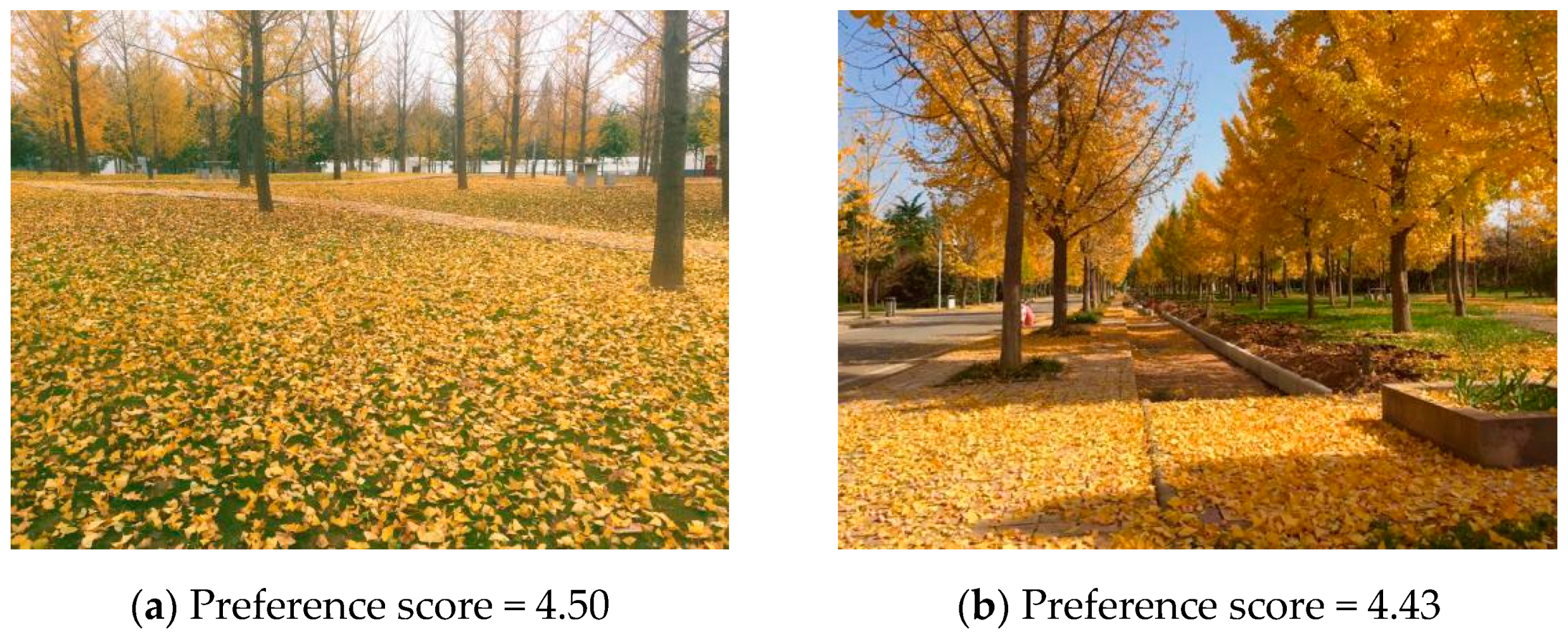

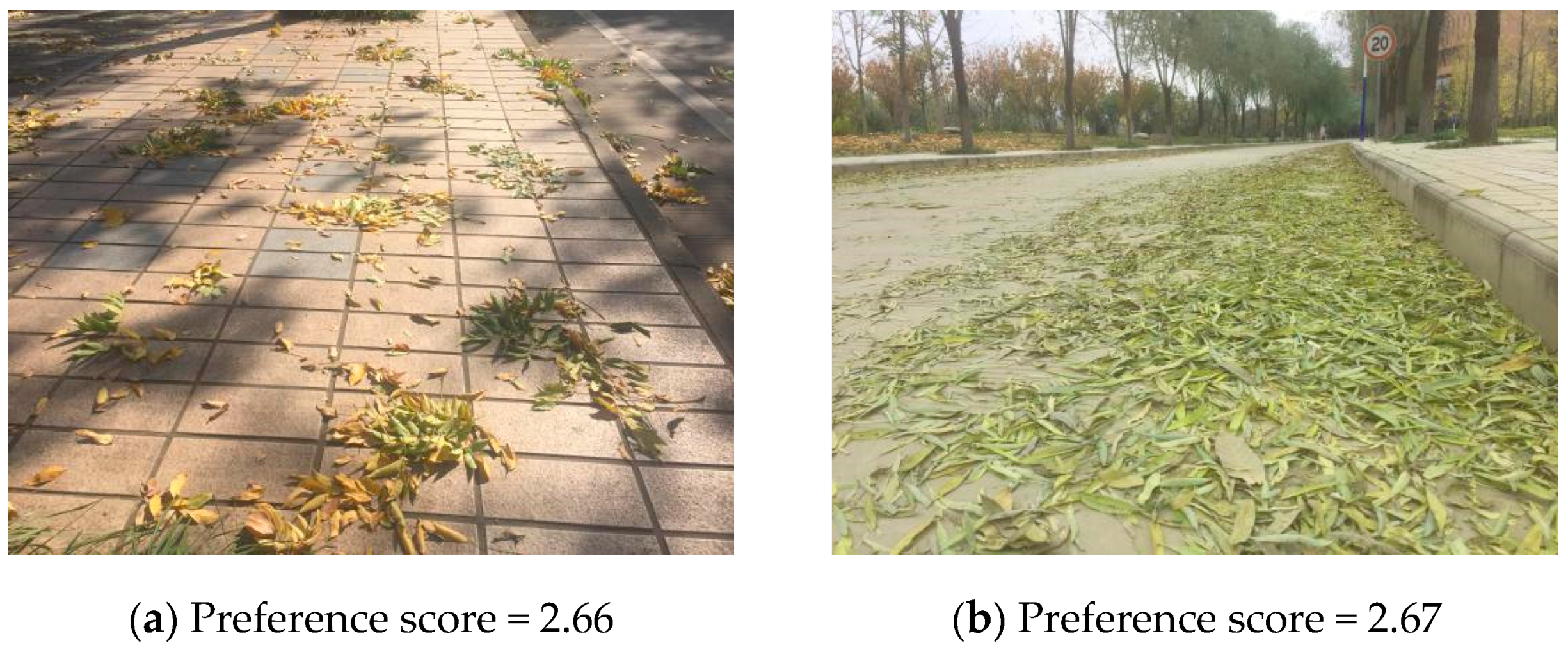

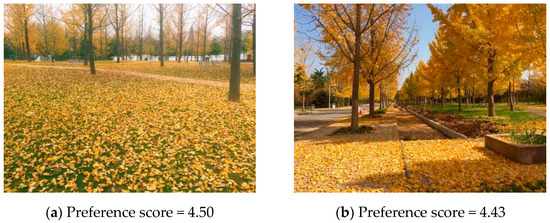

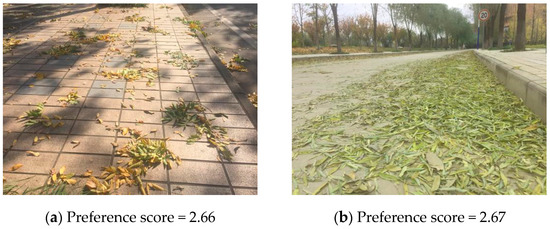

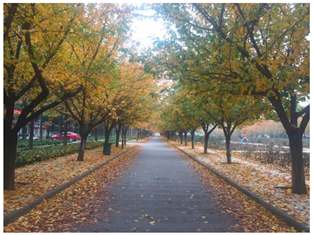

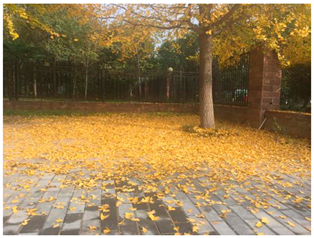

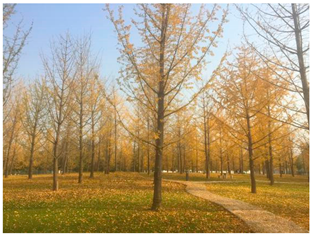

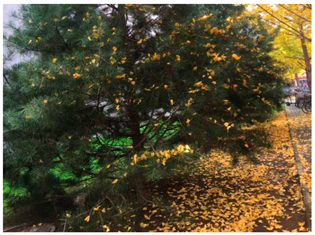

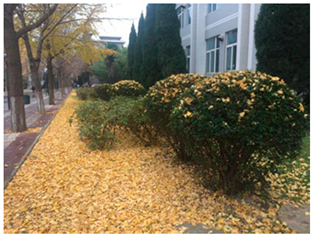

The mean preference score for each photograph was found to be widely distributed from 2.66 to 4.50, and the mean score of all photographs was 3.47, which generally showed preference for deciduous landscape. The photographs which were the most and least appreciated are shown respectively; a (mean ± SD: 4.50 ± 0.76) and b (4.43 ± 0.87) were given the highest mean score (Figure 1), while a (2.66 ± 1.17) and b (2.67 ± 1.23) were given the lowest mean score (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Deciduous landscape photographs with the two highest mean preference scores, representing the delightful scenery with colorful leaves and great maintenance (with an example of evaluation indicators scoring: (a) Color = 1, Amount = 3, Underlying surface = 1, Planting pattern = 2, Other elements = 0. (b) Color = 1, Amount = 3, Underlying surface = 2, Planting pattern = 1, Other elements = 0).

Figure 2.

Deciduous landscape photographs with the two lowest mean preference scores, representing the messy scenery with dim leaves and poor maintenance.

Using the mean preference scores of each picture and the characteristics of the deciduous landscape, the linear regression analysis showed that the color of the leaves was the only reliable predictor for landscape preference, while the amount of the leaves, underlying surface, planting method and other elements did not have significant effects.

3.2. Effects of Demographic Characteristics on Preference

By using linear regression analysis, significant differences were shown among the preference of people of different ages (p = 0.000) and different occupations (p = 0.010). There was no significant difference between different education level groups (p = 0.751) and, surprisingly, different gender groups (p = 0.761).

Among these four characteristics mentioned, the Spearman’s rank correlation analysis (Table 3) only showed a significant correlation between preference scores and ages of respondents (positive). This significant correlation was further proved using the Jonckheere–Terpstra test; the result shows that “age” had a significant influence on preference of respondents while other characteristics did not.

Table 3.

Correlations between the mean scores of deciduous landscape preference of respondents and their demographic variables (age, occupation, education, gender) (Spearman).

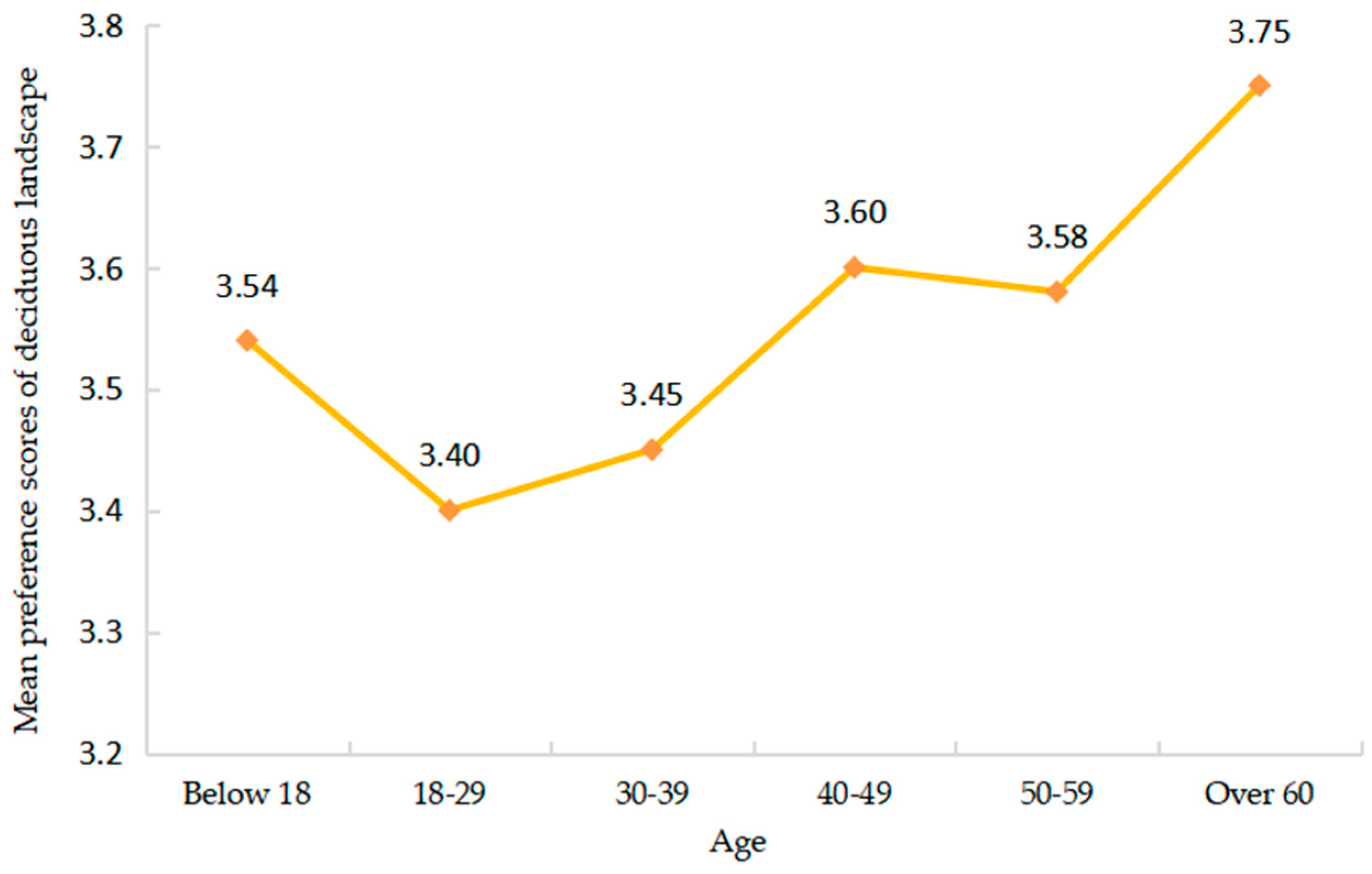

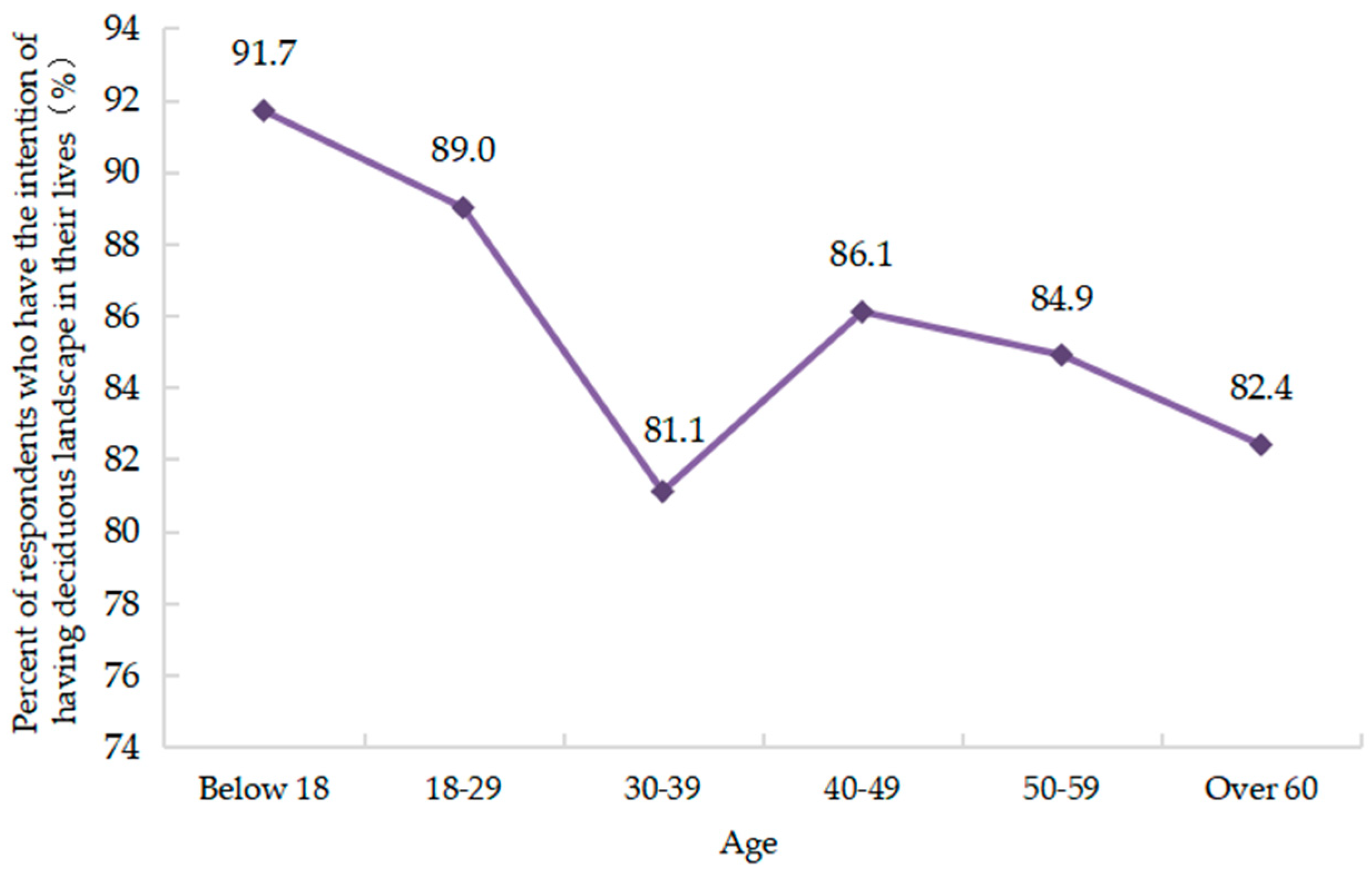

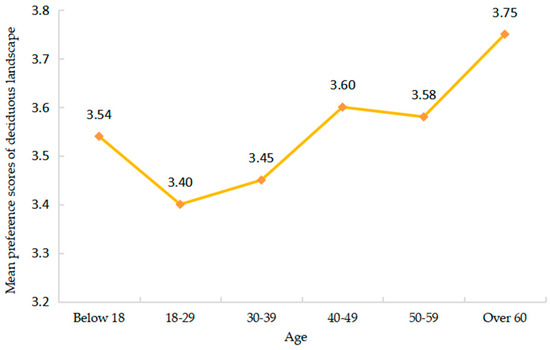

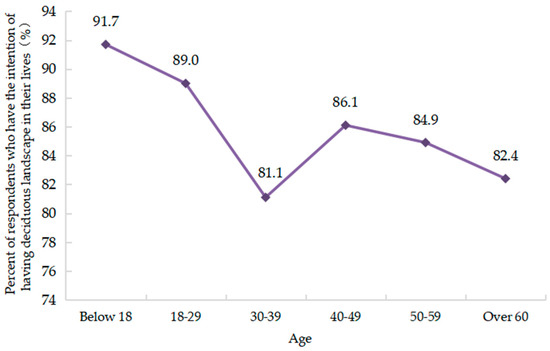

3.3. Age Group Preference and Deciduous Landscape Characteristics

The overall tendency showed that people generally (other than children below 18) showed more preference for deciduous landscape as their age increased (Figure 3), which ranked as: over 60 (mean ± SD: 3.75 ± 0.89), 40–49 (3.60 ± 0.74), 50–59 (3.58 ± 0.68), below 18 (3.54 ± 0.64), 30–39 (3.45 ± 0.81), 18–29 (3.40 ± 0.69). Interestingly, as the age increased, people’s intention to have deciduous landscape in their lives showed a downward trend, which conflicted with the growing preference (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Mean preference scores of deciduous landscape from different age groups of the respondents.

Figure 4.

Percent of respondents from different age groups who have the intention of having deciduous landscape in their lives.

Using the mean preference scores of respondents of different ages, reliable predictors for preference were identified. The linear regression analysis showed that color was the only significant predictor for people under 49, while elderly people who were aged between 50 and 59 can also be affected by underlying surface, and for those over 60, the underlying surface becomes the only significant predictor (Table 4).

Table 4.

Significant predictors (landscape characteristics) for deciduous landscape preference of different age groups from the linear regression analysis.

Further analysis showed that while people of all ages were most attracted by deciduous landscape made up of red or light yellow leaves, people over 60 had a better tolerance toward dark yellow or other unpopular colors such as brown, gray and green. On the other hand, elderly people preferred the lawn as the underlying surface of deciduous landscape, and when the underlying surface included both lawn and road, their preference showed a dramatic decrease as the age increased.

Additionally, the following finding shows the same result: most respondents, regardless of their age, believed that the color of leaves is the most important factor for deciduous landscapes, but elderly people over 60 had a much higher percentage of choosing the rest facilities or the cleanness and safety of the road as the most important factor. While visiting deciduous landscape, elderly people have many other significant differences which are easy to explain: Firstly, compared to other age groups, they had the lowest interest in playing with the fallen leaves; Secondly, elderly people over 50 showed a more positive attitude toward other tourists when younger people tended to give up better deciduous landscape just because of the presence of the crowd; Finally, the acceptable traveling time for elderly people over 60 was significantly decreased compared to younger people, while their ideal residence time increased.

3.4. Other Demographic Groups’ Preference and Landscape Characteristics

People’s preference was only influenced by the color of leaves regardless of their occupation, while retired people were affected by the underlying surface (Table 5), which agreed with the age differences. The average preference score for each occupation ranked as: social (mean ± SD: 3.63 ± 0.80), artistic (3.61 ± 0.74), investigative (3.58 ± 0.70), retired (3.56 ± 0.72), enterprising (3.46 ± 0.78), student (3.46 ± 0.68), realistic (3.39 ± 0.72), conventional (3.29 ± 0.76).

Table 5.

Significant predictors (landscape characteristics) for deciduous landscape preference of different occupation groups from the linear regression analysis.

There was no significant difference between males and females; their reliable predictor was the color of fallen leaves (Table 6). Females (3.48 ± 0.75) showed a slightly higher preference than males (3.47 ± 0.72); at the same time, they had more tendency to keep deciduous landscape in their lives and were more likely to interact with deciduous landscape.

Table 6.

Significant predictors (landscape characteristics) for deciduous landscape preference of different gender groups from the linear regression analysis.

For people with an education level below college, their preference was only affected by color, while graduates were also affected by the amount of leaves (Table 7). Other than high school, the total trend showed that people have higher preference for deciduous landscape as their education level increases, which ranked as high school (3.68 ± 0.72), graduate (3.48 ± 0.63), college (3.45 ± 0.78), middle school (3.28 ± 0.68).

Table 7.

Significant predictors (landscape characteristics) for deciduous landscape preference of different education groups from the linear regression analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Responses to Deciduous Landscape

Deciduous landscape provides a buffer zone between city and nature and offers a nice balance to soften the tension in urban cities. It has been suggested that people tend to give negative responses to low-maintenance landscapes [20], which does not appear to be the case. Contrary to previous study, even though keeping the fallen leaves appears to save time for cleaning, people are still responding well with an average score of 3.47, which is consistent with a previous finding that people prefer a balance between human control and wild nature [21].

When being asked to describe their perception of deciduous landscape, most respondents mentioned positive words such as “life”, “hope”, “romantic”, “peaceful” and “beauty of nature”, but there were also some negative responses such as “time passing by”, “messy”, “depression” and even “sadness”. These opposing reactions are not hard to explain, given that at this stage, because of the lack of theoretical support, the planning and maintaining of deciduous landscape is still spontaneous, which causes different effects (refer to Figure 1 and Figure 2) and divided opinions.

4.2. Influence of Landscape Characteristics and Demographic Characteristics

Landscape characteristics were proven to predict preference better than demographic characteristics [44]. It is similar to our results: even though there is diversity among different groups, the color of leaves appears to be the main determining landscape characteristic, and it works for most people. Thus, for general planning, choosing colorful tree species will be an effective way to improve the quality of deciduous landscape.

The results of this study indicate that age and occupation are the most significant factors for people’s preference of deciduous landscape. Our result shows a significant correlation between age and occupation, and as it turns out, the occupation difference only exists in the retired group, which can be easily explained by age differences and therefore does not require further analysis. Age, on the other hand, has been proven to have a significant effect on landscape preference in much research [45,46], as it did in ours.

4.3. Age Differences and Preference for Deciduous Landscape

Age is the strongest demographic predictor in our research. Previous research mentioned that age has a significant influence on landscape preference, and children and seniors usually have a relatively higher preference [44,47], which is completely consistent with our results.

Elderly people, because of their closeness to nature from childhood, are more eager to connect with nature as their age increases [27] and are also more familiar with deciduous landscape, which might be an explanation for their positive responses. The most interesting finding is that there appears to be a paradox for elderly people: while having the highest preference, they have the lowest intention to keep deciduous landscape in their lives. There are similarities between these results in our study and those described by Howley, which claimed that while water element in landscape is preferred, age has a negative association with water-related landscape preference [23]. Comparison of these findings confirms that these contradictions can be explained by elderly people’s vulnerability to the dangers of these types of landscapes. Earlier research showed that safety is an important characteristic for improving the preference of observers [6], especially for Chinese [48], and elderly people have even stronger preference for safe environment because of their physical conditions and concerns. For elderly people, deciduous landscape can be a potential danger just like water-related landscape: it might be messy, slippery, and it causes walking inconvenience while covering the road. However, they still have the highest preference, and they were not and should not be stopped from enjoying deciduous landscape. While the new policy makes deciduous landscape a new “fashion” in many cities, the ultimate aim is always to improve the quality of people’s life, and what really matters to a city brand is if it is acceptable to all people [49]. Yet, our understanding and attention to this age group were still limited.

Another important finding is that as the age increases, people gradually start to care about underlying surface more than colorful leaves. Elderly people are more tolerant of unpopular dim colors, but they get picky if the fallen leaves cover both lawn and road, which means elderly people tend to give up visual enjoyment for their convenience and safety. This finding also agrees with the results in which elderly people claimed that they cared more about clean, safe road and rest facilities than the beauty of the scenery. Available seats can provide a place for elderly people to rest, watch people and enjoy nature [50]; this finding supports the results of previous studies that the preference for seats increases as the age increases [51], which is easy to believe because of elderly people’s physical conditions.

Previous research showed that elderly people always prefer green space that is easier for them to enter because of their movement inconvenience [51]. This finding is also supported by our research: elderly people tend to spend more time in nearer locations and do not seem to care much about the quality or the crowd, which means they value deciduous landscape as a place to relax and rest, not as a tourist sight.

In conclusion, elderly people have different needs and preferences, and they should be included in the planning process of deciduous landscape. To do that, we should adjust the deciduous landscape to accommodate the elderly, keep it on the lawn and try to maintain the road clean. Therefore, we can increase elderly people’s preference and the likelihood of revisitation and let them be a part of this special seasonal sight without excluding other age groups.

4.4. Other Characteristics and Preference for Deciduous Landscape

This study was unable to demonstrate significant differences among education level groups or gender groups. No significant difference between gender groups agrees with previous research that gender does not have an effect on wild landscape preference [25]. In contrast, education level was proven to have a great influence on landscape preference [52]: people with a higher education level understand more about the benefits of green space and always have more interest in urban parks [9]. Previous research also showed that respondents with a higher education level prefer natural vegetation linked to ecological interests, and many respondents with a lower education level came from the countryside and were more familiar with natural landscape [35], which is similar to the results of the present study although not significant. In this case, education level can be related to age differences, and thus hard to separate (Table 3), and since the site was on the campus, the preference might also be affected by the high familiarity of students other than education level [53].

4.5. Limitations

Our study used a photo survey approach which has been widely used in preference studies, although it still has its limits. The quality of deciduous landscape can be seriously affected by lighting, weather and surroundings, which cannot be fully reflected in photographs. In addition, because of the particularity of deciduous landscape, the composition of the photographs was different, which was proven to affect the preference [54]. Finally, there are many other factors that would have effects on deciduous landscape; for instance, deciduous landscape can be influenced by the seasonal changes themselves, but our research did not take the time of taking photographs into consideration. Moreover, deciduous landscape is under the influence of areas, but our research only included Shaanxi Province, and thus it might not be comprehensive enough to represent the whole landscape preference. Therefore, future research may be needed to explore deciduous landscape preference at different times and in different regions.

5. Conclusions

Understanding the needs and preferences of the target group is an important part of landscape planning: a landscape that considers different people’s preferences and perceptions can meet their needs better, therefore leading to physical satisfaction and positive mental health effects.

Nowadays, people are eager for improving their life quality and well-being from landscape, which requires cooperation with nature and artificial culture [15], and therefore the importance of deciduous landscape has increased. This study, for the first time, explored preference for deciduous landscape of people with different demographic characteristics and provided theoretical support for deciduous landscape which is expected to be useful in both the planning and maintaining process. The results of this paper reveal that age can be a significant factor for deciduous landscape preference, which can be helpful to understand our target group in the planning process of deciduous landscape, especially elderly people. As a new trend in China, the deciduous landscape can strengthen the sense of belonging and well-being, but it cannot be a successful brand until all the local stakeholders are satisfied [49,55,56]. Providing deciduous landscape that takes elderly people’s needs and preferences into consideration could increase the usage by elderly people and potentially improve their health, both physically and mentally. A well-maintained environment was proven to be effective to increase consensus in aesthetic preference judgment [42]; while building deciduous landscapes, we should pay attention to safety and cleanness as well as beauty so that we can improve the preference of elderly people without excluding other age groups. We hope the findings of this study can provide theoretical support and guidance for the future development of deciduous landscape and therefore benefit people of all ages and ensure a balanced nature–city environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su13147615/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F. and W.J.; Methodology, R.F.; Software, R.F. and K.L.; Validation, R.F., J.F. and J.S.; Formal Analysis, R.F.; Investigation, J.S. and R.F.; Resources, W.J.; Data Curation, J.S. and K.L.; Writing–Original Draft Preparation, R.F.; Writing–Review and Editing, R.F. and J.F.; Visualization, J.S., J.F. and R.F.; Supervision, W.J. and J.F.; Project Administration, W.J.; Funding Acquisition, W.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the voluntariness of the respondents and the harmlessness of the research which did not infringe any right of the respondents.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the voluntariness of the respondents and the harmlessness of the research which did not infringe any right of the respondents. The respondents were informed the purpose of the questionnaires in advance.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the volunteers who helped us to hand out the questionnaires and all the 981 respondents in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation or writing of the study.

Appendix A. Questionnaire on Deciduous Landscape Preference

Thank you for taking this questionnaire! We are postgraduates of landscape architecture, we assure you that the results of the questionnaires would only be used on landscape preference related analysis and study, your information will not be revealed or used in any kind of commercial purpose, so please fill in your personal information truthfully. The following 40 photos were taken on campus, please choose how you like the scenery in each photo using the whole scoring scale. Thank you again for your participation.

- 1.

- What does this scenery remind you of?___________________________

- 2.

- Have you ever seen deciduous landscape?□Yes□No□I don’t remember

- 3.

- Do you understand the definition of deciduous landscape?□Yes□Not sure□No

- 4.

- Do you want to have deciduous landscape in your living environment?□Yes, it makes the environment more beautiful□No, it is messy and unsafe□Whatever, I don’t care

- 5.

- Will you bring your family or friends to deciduous landscape?□Yes, definitely□Yes, if there is a chance□No, I rather visit by myself□No, I don’t want to

| 6 | 7 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 8 | 9 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 10 | 11 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 12 | 13 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 14 | 15 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 16 | 17 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 18 | 19 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 20 | 21 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 22 | 23 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 24 | 25 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 26 | 27 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 28 | 29 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 30 | 31 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 32 | 33 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 34 | 35 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 36 | 37 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 38 | 39 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 40 | 41 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 42 | 43 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

| 44 | 45 |

|  |

| □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like | □really don’t like □don’t like □normal □like □really like |

- 46.

- What are your main purposes to visit deciduous landscape? (Multiple choice)□Walk with seniors□Bring kids to nature□Spend time with friends□Enjoy the scenery yourself□Take novel pictures□Kill some time and relax□Others __________

- 47.

- What are the factors matter to you if you are going to visit deciduous landscape? (Multiple choice)□The quality of deciduous landscape□The number of other tourists□Journey time□Ticket price□Others __________

- 48.

- Which one do you think is the most important factor for the quality of deciduous landscape?□Leaves are bright-colored□Leaves are delicate-shaped□Leaves can cover the ground□Waterscape, sculpture or pavilions nearby□Leaves are cleaned up in time□Others _______

- 49.

- How long can you take as journey time to deciduous landscape?□Within 10 min□10–30 min□30–60 min□More than 60 min

- 50.

- How long will you stay at deciduous landscape if you are going to visit?□Within 10 min□About half an hour□About 1 h□About 2 h□Over 3 h

- 51.

- How many times will you visit deciduous landscape?□None, not interested□Once, just to see what it is like□Twice to Three times, it’s fun and I may visit again□Over three times, I love this scenery and want to spend more time

- 52.

- How would you enjoy deciduous landscape if you are going to visit?□Walk while watching□Casually stop-and-go□Find a great place with rest facility, stop to enjoy

- 53.

- How would you feel deciduous landscape if you are going to visit?□Just walking and watching the scenery□Be Interactive—raising, sitting or lying on leaves

- 54.

- Which one will you choose if you are going to visit deciduous landscape?□Excellent deciduous landscape, ten yuan for tickets□Good deciduous landscape, free

- 55.

- Which one will you choose if you are going to visit deciduous landscape?□Excellent deciduous landscape, a lot of tourists□Good deciduous landscape, a couple of tourists

- 56.

- Which one will you choose if you are going to visit deciduous landscape?□Excellent deciduous landscape, half an hour for journey time□Good deciduous landscape, ten minutes for journey time

- 57.

- Gender□Male□Female

- 58.

- Age□Below 18□18–29□30–39□40–49□50–59□Over 60

- 59.

- Current occupation□Full-time student□Retired□Realistic (chefs, mechanics, carpenters, farmers…)□Investigative (scientists, engineers, doctors…)□Artistic (architectures, sculptors, actors, singers…)□Social (teachers, consultants, public relations…)□Enterprising (project managers, salesmen, judges, lawyers…)□Conventional (secretaries, accountants, officers, typists…)

- 60.

- Education level□Below middle school□High school□College□Post graduate or above

References

- Cox, D.T.C.; Hudson, H.L.; Shanahan, D.F.; Fuller, R.A.; Gaston, K.J. The rarity of direct experiences of nature in an urban population. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 160, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnold, M.A. ASHS Presidential Address: Relevancy in the Corporate University—Horticulture’s 21st Century Challenge. Hortscience 2015, 50, 1838–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Kubo, T. Cross-generational decline in childhood experiences of neighborhood flowering plants in Japan. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 174, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchmough, J.; Wagner, M.; Ahmad, H. Extended flowering and high weed resistance within two layer designed perennial “prairie-meadow” vegetation. Urban For. Urban Gree 2017, 27, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, D.; Franco, D.; Mannino, I.; Zanetto, G. The impact of agroforestry networks on scenic beauty estimation—The role of a landscape ecological network on a socio-cultural process. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 62, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.C.; Yue, H.; Zhou, Z.Q. Preferences for urban stream landscapes: Opportunities to promote unmanaged riparian vegetation. Urban For. Urban Gree 2019, 38, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southon, G.E.; Jorgensen, A.; Dunnett, N.; Hoyle, H.; Evans, K.L. Biodiverse perennial meadows have aesthetic value and increase residents’ perceptions of site quality in urban green-space. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, Y.R.; Yuan, T. Public perceptions and preferences for wildflower meadows in Beijing, China. Urban For. Urban Gree 2017, 27, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chen, W.Y. Perception and attitude of residents toward urban green spaces in Guangzhou (China). Environ. Manag. 2006, 38, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khew, J.Y.T.; Yokohari, M.; Tanaka, T. Public Perceptions of Nature and Landscape Preference in Singapore. Human Ecol. 2014, 42, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Homma, R.; Iki, K. Preferences for a lake landscape: Effects of building height and lake width. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 70, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Domesticated nature: Motivations for gardening and perceptions of environmental impact. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Jorgensen, A.; Wilson, E.R. Evaluating restoration in urban green spaces: Does setting type make a difference? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 127, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Wei, S.Y.; Ji, W.L. Deciduous Landscape Construction Based on Landscape Preference. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 27, 106–109. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Sargolini, M. Urban Landscapes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.F. Deciduous landscape street, is it feasible? Environment 2018, 4, 65–67. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.H. Adjust measures to local conditions when building deciduous landscape. China Tourism News, 5 November 2020; 3. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.N. Deciduous Landscape in Public Space. Public Art 2019, 1, 24–33. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T.W.; Yuan, B. Deciduous landscape, scenery or garbage? China Tourism News, 17 December 2014; 3. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, M.; Westermann, J.R.; Kowarik, I.; van der Meer, E. Perceptions of parks and urban derelict land by landscape planners and residents. Urban For. Urban Gree 2012, 11, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.C.; Hansen, G.; Monaghan, P. Optimizing Shoreline Planting Design for Urban Residential Stormwater Systems: Aligning Visual Quality and Environmental Functions. Horttechnology 2017, 27, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Clerici, N.; Staudhammer, C.L.; Feged-Rivadeneira, A.; Camilo Bohorquez, J.; Tovar, G. Trees and Crime in Bogota, Colombia: Is the link an ecosystem disservice or service? Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, P. Landscape aesthetics: Assessing the general publics’ preferences towards rural landscapes. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnarova, K.; Sklenicka, P.; Stiborek, J.; Svobodova, K.; Salek, M.; Brabec, E. Visual preferences for wind turbines: Location, numbers and respondent characteristics. Appl. Energ. 2012, 92, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Koole, S.L. New wilderness in the Netherlands: An investigation of visual preferences for nature development landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, A.; Luca, G.D. Specifying the Significance of Historic Sites in Heritage Planning. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2019, 18, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Briegel, R.; Schupbach, B.; Junge, X. Aesthetic preference for a Swiss alpine landscape: The impact of different agricultural land-use with different biodiversity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 98, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, P.; Donoghue, C.O.; Hynes, S. Exploring public preferences for traditional farming landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 104, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalivoda, O.; Vojar, J.; Skrivanova, Z.; Zahradnik, D. Consensus in landscape preference judgments: The effects of landscape visual aesthetic quality and respondents’ characteristics. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 137, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefner, K.; Zasada, I.; van Zanten, B.T.; Ungaro, F.; Koetse, M.; Piorr, A. Assessing landscape preferences: A visual choice experiment in the agricultural region of Markische Schweiz, Germany. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.L.; Tong, C.M.; Marcus, C.C. What makes a garden in the elderly care facility well used? Landsc. Res. 2019, 44, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Liao, X.; Schuller, K.; Cook, A.; Fan, S.; Lan, G.; Lu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Moore, J.B.; Maddock, J.E. Insights from an observational assessment of park-based physical activity in Nanchang, China. Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 930–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gibson, S.C. “Let’s go to the park.” An investigation of older adults in Australia and their motivations for park visitation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention; European Treaty Series No. 176; Council of Europe: Florence, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J. Demographic groups’ differences in visual preference for vegetated landscapes in urban green space. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 28, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Koppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xi’an City. Available online: https://baike.so.com/doc/5417601-5655749.html (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Climate Data for Cities Worldwide. Available online: https://en.cliamte-data.org (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- He, X.Y.; An, L.; Hong, B.; Huang, B.Z.; Cui, X. Cross-cultural differences in thermal comfort in campus open spaces: A longitudinal field survey in China’s cold region. Build Environ. 2020, 172, 106739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orenstein, D.E.; Zimroni, H.; Eizenberg, E. The immersive visualization theater: A new tool for ecosystem assessment and landscape planning. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 54, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juettler, A.; Schumann, S.; Neuenschwander, M.P.; Hofmann, J. General or Vocational Education? The Role of Vocational Interests in Educational Decisions at the End of Compulsory School in Switzerland. Vocat. Learn. 2021, 14, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.H.; Zhao, J.W.; Liu, Z.Y. Consensus in visual preferences: The effects of aesthetic quality and landscape types. Urban For. Urban Gree 2016, 20, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.W.; Wang, R.H.; Cai, Y.L.; Luo, P.J. Effects of Visual Indicators on Landscape Preferences. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2013, 139, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevenant, M.; Antrop, M. The use of latent classes to identify individual differences in the importance of landscape dimensions for aesthetic preference. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.Q. Measuring and Understanding Public Perception of Preference for Ordinary Landscape in the Chinese Context: Case Study from Wuhan. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, B.; Devereux, B. Assessing public aesthetic preferences towards some urban landscape patterns: The case study of two different geographic groups. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, T. The perception of agrarian historical landscapes: A study of the Veneto plain in Italy. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Pardela, L.; Can, W.; Katlapa, A.; Rabalski, L. Perceived Danger and Landscape Preferences of Walking Paths with Trees and Shrubs by Women. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shirvani-Dastgerdi, A.; De-Luca, G. Boosting city image for creation of a certain city brand. Geogr. Pannonica 2019, 23, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodiek, S.D.; Fried, J.T. Access to the outdoors: Using photographic comparison to assess preferences of assisted living residents. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 73, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Rodiek, S. Older Adults’ Preference for Landscape Features Along Urban Park Walkways in Nanjing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodriguez, S.L.; Peterson, M.N.; Moorman, C.J. Does education influence wildlife friendly landscaping preferences? Urban Ecosyst 2017, 20, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, M.S. Indicators of visual scale as predictors of landscape preference: A comparison between groups. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2882–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svobodova, K.; Sklenicka, P.; Molnarova, K.; Vojar, J. Does the composition of landscape photographs affect visual preferences? The rule of the Golden Section and the position of the horizon. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastgerdi, A.S.; Luca, G.D. Strengthening the city’s reputation in the age of cities: An insight in the city branding theory. City Territ. Archit. 2019, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kulibanova, V.V.; Teor, T.R. Identifying Key Stakeholder Groups for Implementing a Place Branding Policy in Saint Petersburg. Baltic Region 2017, 9, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).