How a Tourism City Responds to COVID-19: A CEE Perspective (Kraków Case Study)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodological Framework

3. Coping with COVID-19: Tourism Response and Recovery at the Urban Destination Level

3.1. COVID-19 Crisis Response Stage

3.1.1. Cooperation with National Authorities

3.1.2. Building Cross-Departmental Collaborations within an Urban System

3.1.3. Maintaining Tourism Businesses and Employment

3.2. Stage Two: Tourism Industry Recovery

3.2.1. Launch of a Data-Driven Phase Model of Action

3.2.2. Advocating Technology-Facilitated Innovation in Tourism

3.2.3. Rebuilding Confidence in Tourism

3.2.4. Providing Continuous Financial Support and Consumption Stimuli

4. Case Study: Kraków

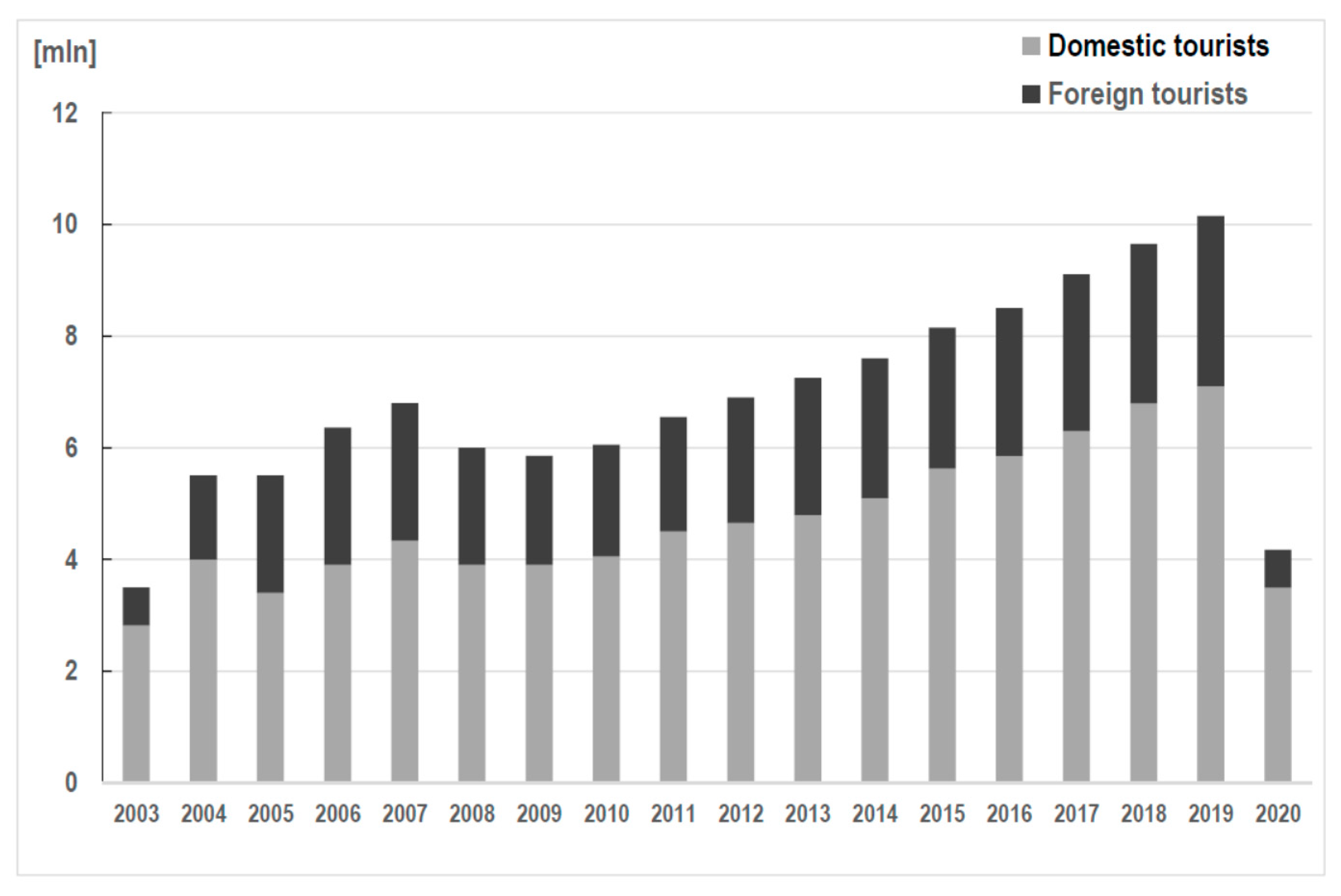

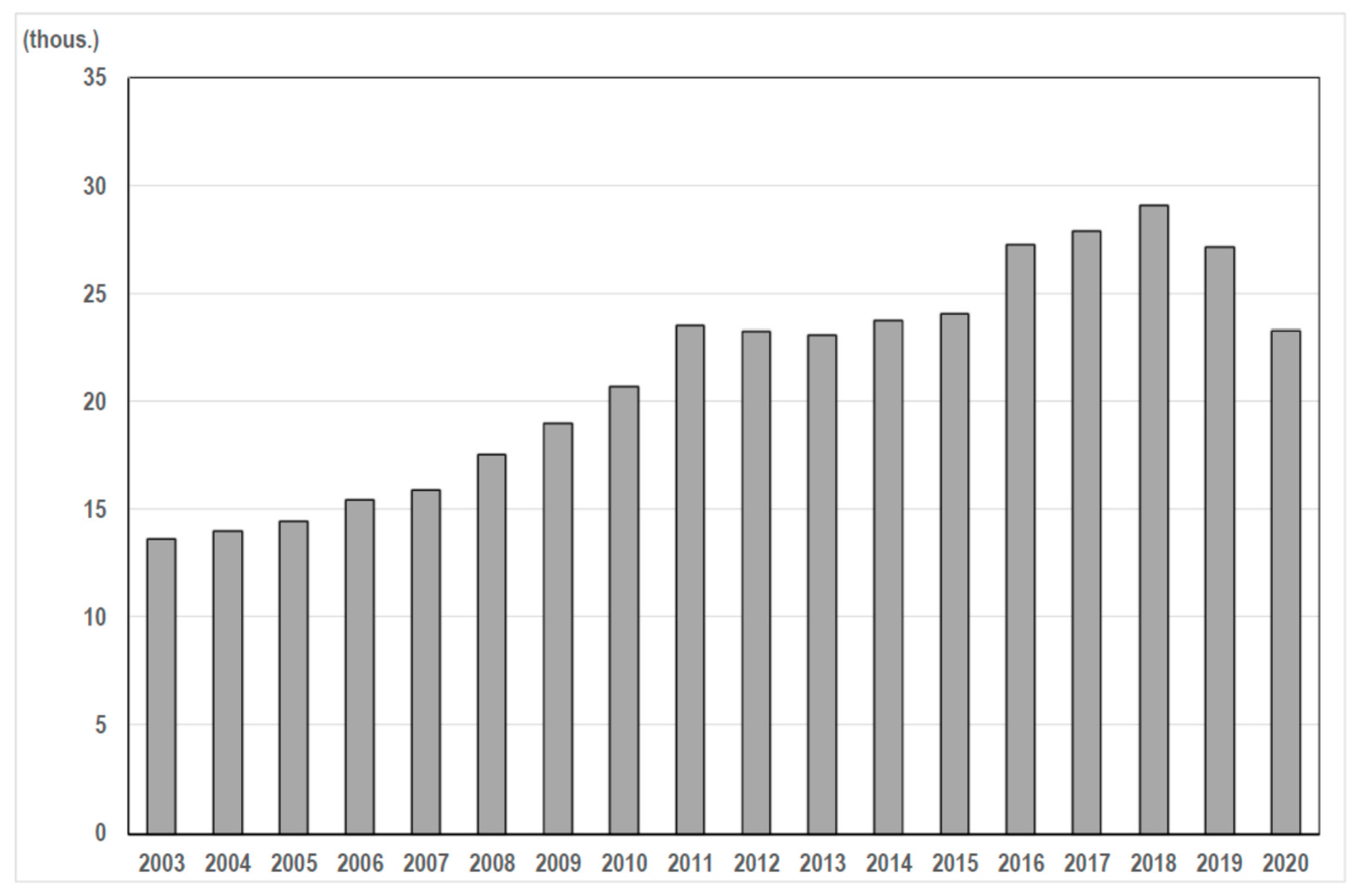

4.1. Tourism in Kraków before COVID-19

4.2. From Lockdown to Recovery

4.3. How Kraków Responded to COVID-19

4.3.1. Activities for the Local Tourism Industry: National Level

4.3.2. Activities for the Local Tourism Industry: Regional Level

4.3.3. Local Authority Action for Tourism Business

Creating a New City Image for Pandemic and Post-Pandemic Times

Local Cooperation for Tourism and New Tourism Programs for the Future

- Kraków’s sustainable tourism policy for 2021–2028

- Kraków Cultural Program, focused on the development of culture and heritage protection

- Kraków Network Protocol.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Will the city’s tourism offering be revised and become more sustainable? Will post-pandemic tourism cities become sustainable tourism destinations and thus become better places to live? As many academics expect [14,15,16], post-pandemic tourism should be more sustainable, and tourist destinations should base their development patterns on sustainable development goals. On the other hand, the practice to date, especially in urban environments, and despite many declarations, has been strongly connected with growth strategies that were strengthening urban tourism hypertrophy [115]. Will the experience of the pandemic crisis and the corrective actions discussed and/or implemented effectively change this? Or are the sceptics who predict the return of ‘business as usual’ right?

- Will culture be a real driver for a post-covid tourism city? And, if so, to what extent? How will the new technological improvements in culture be received by their participants? What will the trajectories of technology acceptance be between different groups (e.g., generations) of recipients (such as cultural visitors)? What will the absorption of new cultural offerings by local communities be? Will any changes become permanent? Murzyn-Kupisz and Hołuj [108] previously indicated that the negative impacts of overtourism can be mitigated to some extent by museums. Will the introduced solutions allow for the effective management of cultural urban attractions that previously carried the stigma of overcrowding and a reduced experience for cultural participants?

- Will ‘being a tourist in one’s own city’, promoted during the pandemic, become a permanent model of leisure activity for inhabitants of tourism cities? Richards [120,121] sees the new practices of cultural tourism in this form. Is it just a temporary fashion or will a permanent new trend develop? A close and important issue related to these questions is destination (tourism city) resilience: will the local demand for culture and leisure be effective in building destination resilience and setting new (e.g., co-creation) frameworks for shaping the relationship between residents and visitors? Finally, referring to the ideas for social inclusion through culture and tourism [122]: will such activities be a driver for strengthening the cultural capital of the local community or will the cultural turn of cities depend on community cultural and social capital?

- The reactions of tourists and other city users to the changes in the tourism city introduced by, and thanks to, the pandemic seem to be equally interesting. Will city tourists absorb and accept the proposed changes? What changes do they expect themselves to see in post-pandemic tourism cities?

- It is also worth referring to the CEE context. Will the support for tourism received in CEE cities allow for the revival of this sector? Which direction will post-pandemic tourism take in CEE cities? Will there be a change in the approach to tourism development in CEE cities, or will laissez-faire still be practiced? Will a model based on growth in international city-break tourism in CEE historical cities be revised? It is also interesting how the pandemic has influenced relations between tourism stakeholders in these destinations. Have they managed, as shown in Kraków, to constitute a front of cooperation between public and private tourism stakeholders? The case of post-Soviet Samarkand (not CEE, but Uzbekistan’s tourism city), described by Wróblewski et al. [123], shows that the challenges may be found in the local tourism industry’s reluctance to cooperate with the authorities, the weaknesses of the organizations that represent the industry, as well as a belief that businesses must solve pandemic-related problems on their own. In other words, with regard to CEE tourism cities, an attractive direction for post-covid research seems to be related to their still ongoing transition and the issue of shaping (institutional and non-institutional) cooperation. As it follows from institutional theory [124], the effectiveness of regulatory and recovery actions depends on the coexistence and mutual support of formal and informal institutions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henderson, J.C. Communicating in a crisis: Flight SQ 006. Tour Manag. 2003, 24, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, E.; Prideaux, B. Tourism Crises: Management Responses and Theoretical Insight; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-7890-3208-2. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; Hui, E.L. Terrorism, economic uncertainty and outbound travel from Hong Kong. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M.; Xu, J.B.; Wong, S.M. Crisis management research (1985–2020) in the hospitality and tourism industry: A review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism, and global change: A rapid assessment of Covid-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis, and disaster management. Ann. Tour Res. 2019, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N.; Ram, Y. National tourism strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour Res. 2020, 103076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNTWO. Worst Year in Tourism History with 1 Billion Fewer International Arrivals. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/2020-worst-year-in-tourism-history-with-1-billion-fewer-international-arrivals (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Pescaroli, G.; Alexander, D. Critical infrastructure, panarchies and the vulnerability paths of cascading disasters. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCartney, G.; Pinto, J.; Liu, M. City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. Cities 2021, 112, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Zare, S. COVID19 and Airbnb: Disrupting the disruptor. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visacovsky, S.E.; Zenobi, D.S. When a crisis is embedded in another crisis. Soc. Anthropol. 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism Economics, City Tourism Outlook and Ranking: Coronavirus Impacts and Recovery. Available online: https://resources.oxfordeconomics.com/hubfs/City-Tourism-Outlook-and-Ranking.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson-Fischer, U.; Liu, S. The Impact of a Global Crisis on Areas and Topics of Tourism Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davahli, M.R.; Karwowski, W.; Sonmez, S.; Apostolopoulos, Y. The Hospitality Industry in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Current Topics and Research Methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G. The impact of the coronavirus outbreak on Macao. From tourism lockdown to tourism recovery. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, K.; Singer, R.; Cui, R. Urban and rural tourism under COVID-19 in China: Research on the recovery measures and tourism development. Tour. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; To, W.M. The economic impact of a global pandemic on the tourism economy: The case of COVID-19 and Macao’s destination-and gambling-dependent economy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCFT. Report on Recovery and Development of World Tourism Amid COVID-19. Available online: https://en.wtcf.org.cn/Research/WTCFAcademicAchievement/2020091419631.htm (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, Design and Method, 4th ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1412960991. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlusiński, R.; Kubal-Czerwińska, M. A new take on an old structure? Creative and slow tourism in Krakow (Poland). J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2018, 16, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, M.; Kurek, W. Ocena i perspektywy rozwoju Krakowa jako ośrodka turystycznego. In Kraków Jako Ośrodek Turystyczny; Mika, M., Ed.; Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ: Kraków, Poland, 2011; pp. 291–304. ISBN 978-83-88424-60-1. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4522-2609-5. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G. A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure. Qual. Inq. 2011, 17, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, S.; Altan, H. Assessing the Implementation of Renewable Energy Policy within the UAE by Adopting the Australian ‘Solar Town’ Program. Future Cities Environ. 2019, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0803957671. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshmehzangi, A. 10 Adaptive Measures for Public Places to face the COVID 19 Pandemic Outbreak. City Soc. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.G.; Peixoto, J.P.J. COVID-19 pandemic: A review of smart cities initiatives to face new outbreaks. IET Smart Cities 2020, 2, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, N.N.; Dimovski, V.; Peterlin, J.; Meško, M.; Roblek, V. Data-Driven Solutions in Smart Cities: The case of Covid-19 Apps. In Proceeding of the WWW ‘21: Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A. Covid-19 crisis: A new model of tourism governance for a new time. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyk, W.; Sołtysik, M.; Oleśniewicz, P.; Borzyszkowski, J.; Weinland, J. Human resources management as a factor determining the organizational effectiveness of DMOs: A case study of RTOs in Poland. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 828–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, I.; Font, X. Changes in air passenger demand as a result of the COVID-19 crisis: Using Big Data to inform tourism policy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M.; Bellini, N.; Rossi, S. Sustainability in Overtouristified Cities? A Social Media Insight into Italian Branding Responses to Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Nowacki, M. Factors influencing Generation Y’s tourism-related social media activity: The case of Polish students. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2020, 11, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A. Technology and the sustainable tourist in the new age of disruption. J. Sustain. Tour 2021, 29, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Fuchs, M.; Baggio, R.; Hoepken, W.; Law, R.; Neidhardt, J.; Pesonen, J.; Zanker, M.; Xiang, Z. e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A call for transformative research. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Chen, P.J.; Lew, A.A. From high-touch to high-tech: COVID-19 drives robotics adoption. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, A.O.; Koh, S.G. COVID-19 and extended reality (XR). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bec, A.; Moyle, B.; Schaffer, V.; Timms, K. Virtual reality and mixed reality for second chance tourism. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.C. The effect of the SARS illness on tourism in Taiwan: An empirical study. Int. J. Manag. 2005, 22, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhamo, G.; Dube, K.; Chikodzi, D. Counting the Cost of COVID-19 on the Global Tourism Industry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 377–402. ISBN 978-3-030-56231-1. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Tourism and Transport: Commission’s Guidance on How to Safely Resume Travel and Reboot Europe’s Tourism in 2020 and Beyond. 2020. Available online: https://europeansting.com/2020/05/13/tourism-and-transport-commissions-guidance-on-how-to-safely-resume-travel-and-reboot-europes-tourism-in-2020-and-beyond/ (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Hao, F.; Xiao, Q.; Chon, K. COVID-19 and China’s hotel industry: Impacts, a disaster management framework, and post-pandemic agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC. ‘Safe Travels’: Global Protocols & Stamp for the New Normal. 2020. Available online: https://wttc.org/COVID-19/Safe-Travels-Global-Protocols-Stamp (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Statistical Office in Krakow. Available online: http://krakow.stat.gov.pl/en/ (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Purchla, J. Kraków Prowincja Czy Metropolia? Universitas: Kraków, Poland, 1996; ISBN 8370523900. [Google Scholar]

- Sýkora, L.; Bouzarovski, S. Multiple transformations: Conceptualising the post-communist urban transition. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, M.K.; Puczkó, L. Post-Socialist Tourism Trajectories in Budapest: From Under-Tourism to Over-Tourism. In Tourism Development in Post-Soviet Nations; Slocum, S.L., Klitsounova, V., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020; pp. 109–123. ISBN 978-3-030-30717-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Tourismification of the Housing Resources of Historical Inner Cities. The Case of Krakow. Studia Miejskie 2019, 35, 9–25. Available online: https://depot.ceon.pl/handle/123456789/19361 (accessed on 20 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kádár, B. Hotel development through centralized to liberalized planning procedures: Prague lost in transition. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romańczyk, K.M. Krakow–The city profile revisited. Cities 2018, 73, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlusiński, R.; Kubal, M. Tradycje turystyczne Krakowa. In Kraków Jako Ośrodek Turystyczny; Mika, M., Ed.; Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ: Kraków, Poland, 2011; pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-83-88424-60-1. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.K.; Klicek, T. Tourism Cities in Post-Communist Countries. In Routledge Handbook of Tourism Cities, 1st ed.; Morrison, A.M., Coca-Stefaniak, J.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 493–507. ISBN 978-042-924-460-5. [Google Scholar]

- Szubert-Zarzeczny, U. Turystyka w Rozwoju Gospodarczym Polski; Wyd. Wyższej Szkoły Zarządzania „Edukacja”: Wrocław, Poland, 2002; ISBN 838770895X. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, W.; Faracik, R. Selected issues in the development of tourism in Krakow in the 21th century. Tourism 2008, 18, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski, K.; Grabiński, T.; Seweryn, R.; Rotter, L.; Mazanek, L.; Grabińska, E. Ruch Turystyczny w Krakowie w 2019 Roku; Monografia; Malopolska Organizacja Turystyczna: Kraków, Poland, 2020; ISBN 978-83-66288-56-0. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski, K.P. Triangulacja Subiektywnych Odczuć Osób Wypoczywających w Krakowie w Aspekcie Poczucia Bezpieczeństwa Osobistego Podczas Rekreacyjnego Pobytu w Destynacji. Badania Diagnostyczne 2008–2018; Małopolska Organizacja Turystyczna: Krakow, Poland, 2019; ISBN 978-83-66029-99-6. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Office. Kraków: Statistical Data, 2021, Warsaw, Poland. Available online: www.bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Jokilehto, J. The World Heritage List. What Is OUV? Defining the Outstanding Universal Value of Cultural World Heritage Properties; International Council on Monuments and Sites: Paris, France, 2008; ISBN 978-3-930388-51-6. Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/435/1/Monuments_and_Sites_16_What_is_OUV.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Kowalska, S. Cultural Heritage in Poland—the Background, Opportunities and Dangers; Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu: Poznań-Kalisz, Poland, 2012; ISBN 978-83-62135-55-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlusiński, R. International inbound tourism to the Polish Carpathians—The main source markets and their growth opportunities. Acta Fac. Studiorum Humanit. Nat. Univ. Prešoviensis Prírodné Vedy Folia Geogr. 2015, 2. Available online: http://www.foliageographica.sk/public/media/27015/2 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Zmyślony, P.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Urban tourism hypertrophy: Who should deal with it? The case of Krakow (Poland). Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmyślony, P.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Dembińska, M. Deconstructing the overtourism-related social conflicts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kruczek, Z. Turyści vs. Mieszkańcy. Wpływ Nadmiernej Frekwencji Turystów na Proces Gentryfikacji Miast Historycznych na Przykładzie Krakowa. Turystyka Kulturowa 2018, 3, 29–41. Available online: http://turystykakulturowa.org/ojs/index.php/tk/article/view/956 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Polityka Zrównoważonej Turystyki Krakowa na lata 2021–2028 [Sustainable Tourism Policy in Kraków 2021–2028], Urząd Miasta Krakowa [Krakow City Council], Kraków 2021. Available online: https://www.bip.krakow.pl/_inc/rada/posiedzenia/show_pdfdoc.php?id=117239&_ga=2.182696230.1617955323.1620064872-98079949.1616671209 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Szromek, A.; Kruczek, Z.; Walas, B. The Attitude of Tourist Destination Residents towards the Effects of Overtourism—Kraków Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pawlusiński, R.; Mróz, K.; Grochowicz, M. Rozwój gospodarki nocnej w miastach historycznych—Aspekty przestrzenne. Przykład krakowskiej dzielnicy Kazimierz. Konwersatorium Wiedzy Mieście 2020, 5, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, N.N. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, 2nd ed.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0812973815. [Google Scholar]

- Urząd Miasta Krakowa [City of Krakow]. Ruch Turystyczny w Krakowie w 2021 [Tourism in Krakow 2021], Department of Tourism. 2021. Available online: https://www.bip.krakow.pl/?sub_dok_id=58088 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Walas, B.; Kruczek, Z. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism in Kraków in the eyes of tourism entrepreneurs. Studia Perieget. 2020, 2, 79–95. Available online: http://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.ceon.element-72ad3faa-9566-3f86-be0e-733ebda5035e (accessed on 15 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Korinth, B.; Ranasinghe, R. Covid-19 pandemic’s impact on tourism in Poland in March 2020. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2020, 31, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Koens, K. The paradox of tourism extremes. Excesses and restraints in times of COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarynowski, A.; Wójta-Kempa, M.; Płatek, D.; Krzowski, Ł.; Belik, V. Spatial Diversity of COVID-19 Cases in Poland Explained by Mobility Patterns—Preliminary Results. SSRN 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duszyński, J.; Afelt, A.; Ochab-Marcinek, A.; Owczuk, R.; Pyrć, K.; Rosińska, M.; Rychard, A.; Smiatacz, T. Understanding COVID-19. Report by the Covid-19 Advisory Team to the President of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 14 September 2020. Available online: https://institution.pan.pl/images/Understanding_COVID-19_final_version.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Krzysztofik, R.; Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Spórna, T. Multidimensional Conditions of the First Wave of the COVID-19 Epidemic in the Trans-Industrial Region. An Example of the Silesian Voivodeship in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochowicz, M. Sytuacja Branży Gastronomicznej w Pierwszych Miesiącach Trwania Pandemii COVID-19 na Przykładzie Krakowa. Urban Dev. Issues 2020, 67, 5–16. Available online: http://obserwatorium.miasta.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/UDI67_Grochowicz.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Dziadosz, P.; Banasik, M. Gastronomia ma dość Lockdownu. Krakowskie Restauracje Otwierają się Mimo Zakazu. Krakow Nasze Miasto. Information Portal KrakowNasze Miasto.pl, 13 January 2021. Available online: https://krakow.naszemiasto.pl/gastronomia-ma-dosc-lockdownu-krakowskie-restauracje/ar/c1-8084495 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Kołodziejczyk, K. Koronawirus im Niestraszny. Kolejne Restauracje Otwierają się dla Klientów, WP Info Portal, 13 January 2021. Available online: https://wiadomosci.wp.pl/koronawirus-im-niestraszny-kolejne-restauracje-otwieraja-sie-dla-klientow-6596717755784064a (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Dziennik Polski [Daily Local Paper]. Czarny Scenariusz dla Krakowa: Tysiące Firm Przetrwa Kryzys, Ale Zostanie Bez Klientów. Rząd im nie Pomoże. Lepsze Wieści Dla Podhala, May 2020. Available online: https://dziennikpolski24.pl/czarny-scenariusz-dla-krakowa-tysiace-firm-przetrwa-kryzys-ale-zostanie-bez-klientow-rzad-im-nie-pomoze-lepsze-wiesci-dla/ar/c3-14995887 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Krakow.pl. [Official Business Portal. City of Krakow]. Mapa Krakowskiej Gastronomii ma Już Miesiąc! November 2020. Available online: https://business.krakow.pl/informacje_na_temat_dzialan_i_projektow_umk/244658,1643,komunikat,mapa_krakowskiej_gastronomii_ma_juz_miesiac_.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Augustyniak, M. Samorząd Terytorialny w ŚWIETLE wybranych Regulacji Ustawy COVID-19 i jej Zmian; Wolters Kluwer: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; ISBN 978-83-8187-988-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dębkowska, K.; Kłosiewicz-Górecka, U.; Szymańska, A.; Ważniewski, P.; Zybertowicz, K. Polskie Miasta w Czasach Pandemii; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; ISBN 978-83-66698-08-6. [Google Scholar]

- Grochowicz, M.; Salata-Kochanowski, P. Działania Miast Podczas Pandemii; Ekspertyzy i Opracowania Badawcze, Obserwatorium Polityki Miejskiej, Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Warszawa-Kraków, Poland, 2020; Available online: http://obserwatorium.miasta.pl/dzialania-miast-podczas-pandemii-raport/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Pomiędzy Nadzwyczajnymi Zadaniami a Ograniczonymi Możliwościami—Samorząd Terytorialny w Czasie Pandemii; Raport Samorząd, Open‘20 Eyes Economy Summit; Fundacja Gospodarki i Administracji Publicznej: Kraków, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://oees.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Raport-samorzad.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Stojczew, K. Ocena wpływu pandemii koronawirusa na branżę turystyczną w Polsce. Prace Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2021, 65, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juszczak, A. Trendy Rozwojowe Turystyki w Polsce Przed i w Trakcie Pandemii COVID-19; Report, PARP Grupa PFR; Instytut Turystyki w Krakowie sp. z.o.o.: Krakow, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://www.silesia-sot.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Ekspertyza_Trendy-rozwojowe-turystyki-w-Polsce-przed-i-w-trakcie-pandemii-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Bercha, O. The impact of coronavirus on small business in Poland. Sci. Notes Ostroh Acad. Natl. Univ. Econ. Ser. 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszak, A.M. Lack of social security of the workers of gastronomic business in Poland due to the epidemic covid-19. OPUS Uluslararası Toplum Araştırmaları Dergisi 2021, 17, 3185–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajkowski, R.; Żukowska, B.A. Family Businesses during the COVID-19 Crisis—Evidence from Poland. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sectio H Oeconomia 2020, 3, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazeta Wyborcza. “Tarcz” Nie Obejmie Wielu Firm Obsługujących Turystów Zagranicznych. Odbije SIĘ to na budżecie Krakowa, September 2020. Available online: https://krakow.wyborcza.pl/krakow/7,44425,26334161,turystyczna-tarcza-nie-dla-krakowa.html. (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Wasza Turystyka [Internet Tourism Information Portal]. Sejm Uchwalił Ustawę o Bonie Turystycznym, June 2020. Available online: https://www.waszaturystyka.pl/sejm-uchwalil-ustawe-o-bonie-turystycznym/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Ministry of Economic Development, Labour and Technology. [Official Website]. Tourist Voucher. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/development-labour-technology/tourist-voucher (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Wirtualna Polska [Internet Information Portal]. Bon Turystyczny. Problemy z Aktywacją i Skargi, September 2020. Available online: https://finanse.wp.pl/bon-turystyczny-problemy-z-aktywacja-i-skargi-6551361602878272a (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Bankier.pl [Internet Information Portal]. Trzeba Powiązać Wsparcie dla Turystyki ze Spadkiem Obrotów, a nie z Kodem PKD, December 2020. Available online: https://www.bankier.pl/wiadomosc/KO-Trzeba-powiazac-wsparcie-dla-turystyki-ze-spadkiem-obrotow-a-nie-z-kodem-PKD-8021731.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Zarządzenie nr 7. Ministra Rozwoju, Pracy i Technologii z dnia 26 stycznia 2021 r. w sprawie utworzenia Rady Ekspertów do spraw Turystyki [Ordinance No. 7 of the Minister of Development, Labor and Technology of 26 January 2021 on the establishment of the Tourism Experts Council], Dz.Urz.MRPiT.2021.8. Available online: https://sip.lex.pl/akty-prawne/dzienniki-resortowe/utworzenie-rady-ekspertow-do-spraw-turystyki-35852436 (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Pandemic and Tourism in Małopolska till 2021, Interview with Grzegorz Biedron (CEO, DMO Małopolska), 10 June 2020, Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.forum-ekonomiczne.pl/pandemic-and-tourism-in-malopolska-till-2021/?lang=en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Malopolska. [Malopolska Voivodiship Official Website]. Małopolska Turystyka Kontra Koronawirus, March 2021. Available online: https://www.malopolska.pl/aktualnosci/turystyka/walka-z-koronawirusem-a-malopolska-turystyka (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Malopolska. [Malopolska Voivodiship Official Website]. Certyfikat “Małopolska—Bezpieczna Turystyka”, August, 2020. Available online: https://www.malopolska.pl/aktualnosci/turystyka/certyfikat-malopolska-bezpieczna-turystyka (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Krakow Nasze Miasto [Local Information Portal]. Zamieszanie Wokół Tarczy Antykryzysowej, September 2020. Available online: https://krakow.naszemiasto.pl/zamieszanie-wokol-tarczy-antykryzysowej-przedsiebiorcy/ar/c3-7878429 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Urząd Miasta Krakowa [City of Krakow], Pauza Program dla Przedsiębiorców [Program Pauza—Support for Business in COVID-19 time], Zarządzenie Prezydenta UMK.; March 2020. Available online: https://www.bip.krakow.pl/?dok_id=124203 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Krakow Nasze Miasto [Local Information Portal]. Przedsiębiorcy Mogą Wysyłać Wnioski o Obniżenie Stawek Czynszowych w Lokalach Miejskich, February 2021. Available online: https://krakow.naszemiasto.pl/krakow-przedsiebiorcy-moga-wysylac-wnioski-o-obnizenie/ar/c3-8124859 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Bądz Turysta w Swoim Miescie [Official Website]. Available online: badzturysta.pl/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- The #zwiedzajKrakow [#visitKrakow] Program Regulations Implemented as Part of the Krakow Undiscovered Promotional Campaign. Available online: http://media.krakow.travel/get/47312 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Information Brochure Staying Safe in Krakow. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjnv7iEuI_xAhXByYUKHecBDH0QFjAAegQIBBAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.krakow.pl%2Fzalacznik%2F334202&usg=AOvVaw3qEhU8DounMhyimruarwQU (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Kraków‘Culture [Official Website]. Available online: https://krakowculture.pl/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Murzyn-Kupisz, M.; Hołuj, D. Museums and Coping with Overtourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krakow Network Protocol. 2021. Available online: https://krakownetwork.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Krakow_Network_Protocol_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Kaohsiung Protocol. Strategic Recovery Framework for the Global Events Industry, ICCA. Available online: https://www.iccaworld.org/cnt/docs/ICCA%20Kaohsiung%20Protocol.pdfttps://www.iccaworld.org/newsarchives/archivedetails.cfm?id=4090333 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Szromek, A.R.; Kruczek, Z.; Walas, B. Stakeholders’ attitudes towards tools for sustainable tourism in historical cities. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nientied, P.; Toto, R. Learning from overtourism: New tourism policy for the city of Rotterdam. Urban Res. Pract. 2020, 13, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P. Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19) Cities Policy Responses, July 2020. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/cities-policy-responses-fd1053ff/ (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Hipertrofia Turystyki Miejskiej–Geneza i Istota Zjawiska. Konwersatorium Wiedzy Mieście 2019, 32, 7–18. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11089/35068 (accessed on 20 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Rutynskyi, M.; Kushniruk, H. The impact of quarantine due to COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry in Lviv (Ukraine). Problem. Perspect. Manag. 2020, 18, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, D.; Arnaboldi, M.; Lampis, A. Italian state museums during the COVID-19 crisis: From onsite closure to online openness. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2020, 35, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, B.M. Integrating culture in post-crisis urban recovery: Reflections on the power of cultural heritage to deal with crisis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct 2021, 60, 102277. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/35681 (accessed on 15 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council. A Common Path to Safe and Sustained Re-opening, Brussels 17.3.2021, COM 129 final. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/communication-safe-sustained-reopening_en.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Richards, G. Tourists in their own city—Considering the growth of a phenomenon. Tour. Today 2016, 16, 8–16. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/34925642/Tourists_in_their_own_city_published_version (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Richards, G. Rethinking Cultural Tourism; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1 78990-543-4. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N. Cultural sustainability, tourism, and development: Articulating connections. In Cultural Sustainability, Tourism and Development. (Re)articulation in Tourism Context; Duxbury, N., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-036-720-175-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewski, S.; Patterson, I.; Nartov, P. Institutional advancement as a reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic in the tourim city of Samarkand, Uzbekistan. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2021, 8, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautet, F. The Role of Institutions in Entrepreneurship: Implications for Development Policy. Bus. Public Adm. Stud. 2020, 14, 29–35. Available online: https://www.bpastudies.org/index.php/bpastudies/article/view/242 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Grochowicz, M.; Pawlusiński, R. How a Tourism City Responds to COVID-19: A CEE Perspective (Kraków Case Study). Sustainability 2021, 13, 7914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147914

Kowalczyk-Anioł J, Grochowicz M, Pawlusiński R. How a Tourism City Responds to COVID-19: A CEE Perspective (Kraków Case Study). Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147914

Chicago/Turabian StyleKowalczyk-Anioł, Joanna, Marek Grochowicz, and Robert Pawlusiński. 2021. "How a Tourism City Responds to COVID-19: A CEE Perspective (Kraków Case Study)" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147914

APA StyleKowalczyk-Anioł, J., Grochowicz, M., & Pawlusiński, R. (2021). How a Tourism City Responds to COVID-19: A CEE Perspective (Kraków Case Study). Sustainability, 13(14), 7914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147914