Abstract

The advent of fintech is blowing a new wind into the financial industry. New business models have been created and consumers’ access to financial services is higher than ever. Internet-only banks based on advanced information technologies have emerged as a leader in the fintech industry, and these banks are fiercely competing with large banks using internet banking as a weapon to attract new customers. The purpose of this study is to explore the factors that influence customers’ intention to switch to internet-only banking services from traditional internet banking services in Korea. To this end, a research model was developed based on the push-pull-mooring model (PPM), which is a migration theory. The research model was analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The findings will provide the practitioners of the new internet-only bank with strategic guidance for attracting new customers and help practitioners of traditional banks to retain current customers.

1. Introduction

With the recent development of mobile technology, fintech services that combine information technologies with existing financial industries are rapidly growing. Fintech is a compound word for finance and technology, which means information technology-driven changes in the financial industry based on advanced information technologies such as mobile, big data, and social network services (SNS). The fintech industry is rapidly increasing globally following the development of fourth industrial revolution-based technologies such as big data, artificial intelligence (AI), block chain, the internet of things, deregulation of fintech companies, and changes in consumer expectations of digitization. Appropriate responses to these rapid changes and growth can bring about the sustainable development of the national economy. Therefore, some countries are already attempting to foster the fintech industry as a national initiative and, based on such initiatives, internet only-banks have been established and operated. Internet-only banks refer to no-store banks that provide financial services through non-face-to-face authentication based on the internet, mobile, automated teller machines (ATMs), and call centers. In today’s fourth industrial revolution era, internet-only banks are a new field of the financial industry, offering improved consumer convenience, easy accessibility, and personal profitability, and can bring about the development of the financial industry based on new innovative technologies. Thus, major countries on the basis of economies in the world are already encouraging fintech companies to establish and operate internet-only banks, and governments expect these banks to act as a driving force to transform existing store-oriented banks into more innovative ones and to serve as a catalyst for financial market development.

As mentioned above, internet-only banks have recently emerged as the core of the fintech industry [1] that leads the future of finance and are expected to have a huge impact on financial consumers; however, research on internet-only banks so far is very limited. In particular, though internet-only banks are playing a role in replacing traditional banks’ internet banking, little is known about this. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the intention of consumers to switch to internet-only banks from traditional banks’ internet banking. To this end, in this study, we developed a research model using a push-pull-mooring (PPM) model, which is the most widely used theory in research related to the switching behavior of consumers toward services or products, and empirically analyzed it for Kakao Bank, Korea’s leading internet-only bank. Although numerous studies on internet banking, including mobile banking, have been conducted before, this study differs from these studies in two aspects. First, this study used the PPM model in terms of switching rather than the technology acceptance model (TAM) [2], which has often been used as a theoretical basis for user acceptance in establishing the research model [3]. Second, this research topic was set as the internet-only bank, which is the latest fintech area, not the internet banking of the traditional bank.

The study is anticipated to provide a theoretical basis for follow-up studies to analyze the transition to new innovative technology-based services. In addition, in practice, it will provide strategic guidelines for practitioners of new internet-only banks to attract new customers and, conversely, help practitioners of traditional banks to retain current customers. Therefore, it is expected to contribute to the sustainable development of the national economy by activating competition in the financial industry between new internet-only banks and traditional banks.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Internet-Only Banks

An internet-only bank refers to a bank that provides most of its banking services in cyberspace with no or very few branches, using personal computers and mobile. Inter-net-only banks perform almost all financial services online, such as opening financial accounts using a non-face-to-face authentication method, loans, bank transfers, and remittances abroad, which traditional banks do through offline branches [4].

Internet-only banks are similar to traditional banks’ internet banking in that they provide financial services to customers using the internet. As traditional banks strengthen their internet banking functions, the difference in service between internet-only banks and internet banking is reducing. In particular, some traditional banks are actively participating as major shareholders in internet-only banks. However, internet banking is a convenient and supportive information system for customers of traditional banks that allows banking on mobile or on the internet, which is only available when customers register at an offline branch. In other words, traditional banks conduct face-to-face business activities in offline branches and use non-face-to-face channels using internet banking as an additional service method. In contrast, internet-only banks do most of their business using only electronic media such as ATMs, mobile, and the internet as the primary channels for transactions with customers. In particular, internet-only banks have recently provided financial transaction services using short message services (SMS) or internet messengers that are not available in internet banking. Internet-only banks partially overlap with internet banking functions, but perform all banking transactions related to customers such as account opening, cash withdrawals, account transfers, loans, and payments in a non-face-to-face manner using the internet. In summary, internet-only banking is fundamentally different from the internet banking of traditional banks that use the internet as a secondary vehicle, in terms of conducting all business in cyberspace [5].

2.2. Literature Review on Internet Banking

Internet-only banks are actively utilizing the latest information technologies, such as AI, big data, and SNS, with some similarities to internet banking because they use the internet and, in particular, mobile technologies as customer contact channels. As internet-only banks use the internet as a technological base, a wide range of studies on the existing customer’s intention to use internet banking was reviewed for this study.

Most of the existing internet banking studies and research models were developed and analyzed based on various theories to analyze the customer’s intention of using internet banking. The theoretical frameworks used in these studies are the TAM of Davis [2], the theory of reasoned action (TRA) of Fishbein and Ajzen [6], the theory of planned behavior (TPB) of Ajzen [7], the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) of Venkatesh et al. [8], diffusion of innovation (DOI) of Rogers [9], the theory of trust and perceived risk, norm theory [10], the D&M IS success model of DeLone and McLean [11,12], and task technology fit (TTF) of Goodhue and Thompson [13,14]. In these studies, research frameworks have used the variables of existing theories, which are perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of the TAM: subjective norms, attitude to use, and perceived behavioral control of the TRA and the TPB, relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, observability, and trialability of the DOI, performance, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions of the UTAUT, system quality, information quality, service quality of the D&M IS model, the task characteristics, task technology fit, technology characteristics of the TTF model, trust and perceived risk.

Previous studies have added a variety of variables to these fundamental theories to build their research models that can be classified into: technical characteristics variables of the internet and mobile banking, characteristics variables of banks, propensity and characteristic variables of customers, and external environment variables. The technical characteristics variables are accessibility, content, convenience, design, feature availability [15], image [16,17], privacy and security [18], speed [15], and web service quality [18]. The characteristics variables of banks are bank management and image [15], banks initiative [17], customer feedback [18], fees and charges [15], perceived credibility [19], and technical support [20]. Propensity and characteristic variables of customers are self-efficacy [17], personal innovativeness [21], personal and media norms [22], web usage intensity [21], and prior e-shopping experience [21]. Finally, the external environment variables include government support [23].

2.3. The Push-Pull-Mooring Model

The push-pull-mooring (PPM) model is a migration theory that includes the mooring effect suggested by Moon [24] with the push-pull model [25] published in the 1880s to describe human migration. Originally, the PPM model was developed to describe human cultural and geographical movements, but it has also been applied as a useful theoretical basis for explaining the determinants of consumers’ service switching behavior to better services or products [26]. The PPM model consists of three effects to describe human migration: the push effect, pull effect, and mooring effect. First, the push effect refers to factors that induce people to leave their place of origin. Second, the pull effect refers to factors that attract people to a destination. Third, the mooring effect refers to intervention variables for push and pull effects that facilitate or inhibit the determination of movement. Due to these three effects, it is explained that people move from their existing settlements to new places. Since the PPM model can also be adapted to explain the transition from familiar habits and behaviors to new behaviors by existing individuals, it has been used as a useful theoretical framework to describe the actions of consumers and organizations in the fields of marketing and organizational behavior [26,27,28] recently, it has also been used in examining online behavior in the field of information and communication technology [29,30,31,32]. Table 1 shows previous studies on switching services or technologies based on the PPM model.

Table 1.

Research on switching intention based on the PPM model.

Previous studies on switching services or technologies showed that push effects have been related to dissatisfaction, low quality, high prices, and low trust, yet these factors were found to have a positive effect on the customers’ switching behavior. On the contrary, pull factors have been related to alternative attractiveness, relative advantage, enjoyment, peer influence, etc., and these factors were also found to have a positive effect on customers’ switching behavior. Mooring factors are related to factors such as switching cost, subjective norm, habit, and inertia, and were found to have a negative effect on the customer’s switching behavior.

3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Research Model

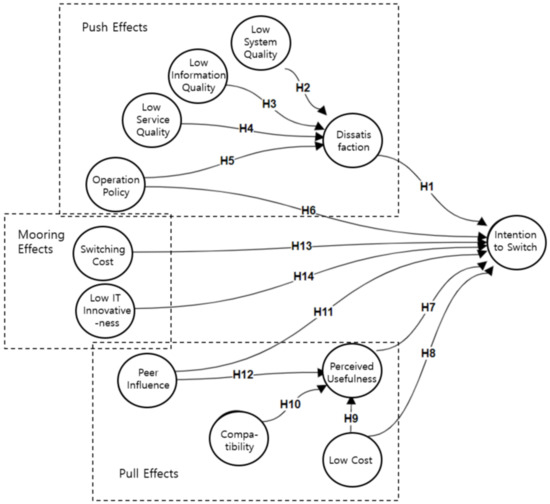

This research model is based on the PPM model consisting of push effects, pull effects, and mooring effects. The variables of the research model were derived from existing internet banking and switching behavior studies. Perceived usefulness, system quality, information quality, and service quality were derived from the technical characteristics of internet banking because they encompass technical characteristic variables such as accessibility, content, convenience, and availability that have been previously presented in the internet banking literature. The operational policy is derived from the nature of the bank in that it determines how the bank operates, including customer feedback and fees. IT innovativeness is a representative individual characteristic variable related to the use of information technology; thus, it was derived as a variable indicating the characteristics of internet banking customers. Finally, dissatisfaction, switching cost, low cost, and peer influences, which were most frequently used in switching behavior studies, were derived as variables of the research model. The research model posits that low system quality, low information quality, low service quality, and operation policy influences dissatisfaction. In addition, peer influences, low cost, and compatibility influence perceived usefulness. Consecutively, dissatisfaction, perceived usefulness, switching cost, and low IT innovativeness influence the intention to switch to internet-only banking. Figure 1 represents this research model.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.2. Push Effects

The push effects drive customers to switch to an alternative service or product, and this effect results from negative factors for incumbent services or products. The proposed model considered dissatisfaction, low system quality, low information quality, low service quality, and operation policy as push factors.

3.2.1. Dissatisfaction

Dissatisfaction refers to feelings that follow the failure to meet expectations or hopes. Many PPM researchers argue that dissatisfaction has a push effect on individuals’ migration decisions [38]. Zengyan et al. [34] stated that dissatisfaction is more closely related to switching intentions because most people migrate due to dissatisfaction with the original place. In services-related research, customer dissatisfaction is considered an indicator of switching intentions. The relationship between customer dissatisfaction with a service provider and switching intentions has been well supported in previous studies [26]. In the information systems (IS) literature, user satisfaction, IS success variable that increases the use of IS and increases personal performance [11], has been known to have a positive effect on the continued use of IT [52]. Conversely, it is argued that dissatisfaction with incumbent IT has a positive effect on switching intentions [36]. Many researchers found that dissatisfaction has a positive effect on users’ switching behavior across different IT, such as SMS and instant messaging applications [32,33]. Therefore, customers’ dissatisfaction with the incumbent internet banking is expected to act as a push factor affecting the switching to internet-only banking. Thus, the following hypothesis was established:

Hypothesis 1.

Dissatisfaction with incumbent internet-banking positively affects the intention to switch to internet-only banking.

3.2.2. Information System Quality

In the IS literature, user satisfaction has been known to be formed by the quality of IS, such as system quality, information quality, and service quality [53]. System quality is the performance of the information system itself, and measures such as response time, ease of use, system reliability, and security have been used to evaluate system quality [54]. System quality has been empirically analyzed suggesting its effect on user satisfaction with studies of various information technologies. Information quality is an output of an information system, which includes measurement indicators such as relevance, usefulness, up-to-date information, and ease of understanding. Information quality has also been empirically analyzed as having a profound effect on user satisfaction with studies targeting various information technologies as well as system quality. Service quality, which has been used as a key variable of customer satisfaction with marketing literature, has been claimed to have a great influence on information system user satisfaction and has been empirically analyzed. Service quality is an evaluation of the service provided by an information system provider and includes measurement indicators such as responsiveness, assurance, and reliability.

In internet banking literature, Koo et al. [12] found that system quality and information quality positively influence customer satisfaction with relation to internet banking use. Tam and Oliveira [55] also empirically analyzed that system, information, and service quality had a positive effect on user satisfaction with mobile banking. Conversely, dissatisfaction with incumbent internet banking can be formed by the system, information, and service quality. According to Tam and Oliveira [55], poor system quality can increase the difficulty of using mobile banking, resulting in user dissatisfaction with mobile banking services. Weak information quality would negatively affect the satisfaction of users with mobile banking services because users spend a lot of effort finding information. In addition, poor service quality can affect the user’s trust, which may negatively affect the satisfaction with mobile-banking services [55]. Therefore, we set the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2.

Low system quality positively affects dissatisfaction with incumbent internet banking.

Hypothesis 3.

Low information quality positively affects dissatisfaction with incumbent internet banking.

Hypothesis 4.

Low service quality positively affects dissatisfaction with incumbent internet banking.

3.2.3. Operation Policy

Due to its technical nature, internet banking provides customers convenient financial transactions, improving space and time limits. However, banks set different operating policies to ensure efficient internet banking operations and safe customer financial transactions. The operational policies of internet banking include procedures for collecting and agreeing on personal information, methods of authentication for transactions (e.g., security cards and one-time passwords (OTP)), closing hours and backup hours, exceeding the number of password errors, limiting the number of daily deposits and withdrawals, and remittance fees. These may limit the convenience and autonomy of some customers. For example, banks with early closing times and long backup times may limit customers’ convenience when using internet banking to handle financial transactions at any time, and if OTP become a necessity for every transaction, including small transactions, it may lead to customer dissatisfaction. In addition, if the number of password errors permitted is low, the safety of the customer can be enhanced, but it can cause inconvenience due to the number of password errors exceeded. In particular, internet banking’s operating policy that mandates customers to visit offline stores due to an exceeded number of password errors may affect the transition to internet-only banking, which handles all such transactions online. Therefore, we set the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5.

Operation policy of incumbent internet banking positively affects the intention to switch to internet-only banking.

Hypothesis 6.

Operation policy of incumbent internet banking positively affects dissatisfaction with incumbent internet banking.

3.3. Pull Effects

Pull effects draw customers toward alternative services or products, and these effects are created by positive factors of alternative services or products. The proposed model considered perceived usefulness, low cost, compatibility, and peer influences as pull factors.

3.3.1. Perceived Usefulness

Previous studies of service switching showed that if new providers had better service, lower prices, and polite staff, customers would more likely move from their current provider [56]. Similarly, people will use new technology or services if it helps them work more efficiently. Perceived usefulness is the degree to which an individual believes that using a particular technology will enhance his or her ability to perform a job [2]. The perceived usefulness in the information technology literature was analyzed as the factor that has the greatest influence on users’ acceptance of new technology. Furthermore, in internet banking literature, perceived usefulness has been suggested as the most important factor that influences customers’ acceptance of internet banking and has been empirically analyzed. Therefore, we established the following hypothesis concerning the perceived usefulness of internet-only banking:

Hypothesis 7.

The perceived usefulness of internet-only banking positively affects the intention to switch to internet-only banking.

3.3.2. Low Cost

In studies pertaining to switching intention based on the PPM model, the attractiveness of alternatives has been suggested as the most important pull factor. In the marketing field, low-price products or low-cost services have been considered as attractive factors for customers to purchase the product or use the service. The advantages of internet-only banks are that they exempt transaction fees when using internet banking compared to existing banks, provide higher interest rates in terms of receiving rates by reducing the fixed costs through no-store policy, and provide cost reduction benefits through medium-rate loans. According to the Bank of Korea which is not a for-profit commercial bank, but a state-run banks that oversees commercial banks, internet-only banks reduce non-interest costs for liquid deposits by one third compared to traditional banks through non-face-to-face channels, reducing the cost incurred by customers. The cost of using internet-only banks, which is lower than that of traditional banks, is recognized as an attractive factor for customers and is expected to affect customers’ adoption of internet-only banks. Therefore, we set the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 8.

Low cost of internet-only banking positively affects the intention to switch internet-only banks.

Hypothesis 9.

Low cost of internet-only banking positively affects the perceived usefulness of internet-only banks.

3.3.3. Compatibility

Compatibility is the extent to which innovation is perceived to be consistent with existing values, past experiences, and potential adopters’ needs [9]. In the case of high compatibility, it has been shown that the probability of adopting innovation is very high [57]. Internet-only banks provide deposit and loan products tailored to the customer’s lifestyle and various customized services through big data analysis [5]. Therefore, the high compatibility of internet-only banks through customer customization services can enhance the perceived usefulness of internet-only banking. Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 10.

Compatibility of internet-only banking positively affects the perceived usefulness of internet-only banks.

3.3.4. Peer Influence

As a component of subjective norms, peer influence has been considered an important factor affecting behavior, such as adopting new technologies [58]. Many researchers [35,37,48] presented and empirically analyzed the peer influence as a pull factor that affects user intentions in using interactive technologies, such as SNS. Internet-only banks provide functions that enable financial transactions using messengers that are already used for customer convenience. The customers of Kakao Bank, which is an internet-only bank in Korea, can send money to friends using KakaoTalk, a messenger without an account number or public certificate. When people receive a remittance request from their friend via messenger, they will more likely process the banking transaction within that messenger. To revitalize financial transactions using messengers, KakaoTalk invites friends to a meeting account and enhances the ability to check the balance, deposit, and withdrawal status with friends. Thus, it is inferred that this method of financial transaction using messengers will increase peer influence in the use of internet-only banks, a new technology. Therefore, the following hypothesis is established:

Hypothesis 11.

Peer influence positively affects the intention to switch to internet-only banks.

As described above, it is expected that peer influence will have a direct influence on the customer’s intention to switch to an internet-only bank, and it is inferred that peer influence will be useful because many friends recommend using internet-only banks. Therefore, the following hypothesis is also established:

Hypothesis 12.

Peer influence positively affects the perceived usefulness of internet-only banks.

3.4. Mooring Effects

Mooring effects are situational and personal factors that can either keep consumers with the incumbent service or facilitate switching to an alternative service. In the proposed model, we suggest switching costs as a situational factor and low IT innovativeness as a personal factor.

3.4.1. Switching Cost

Previous switch behavior studies suggested that switching costs are the most frequently used mooring factor (see Table 1). These studies argued that high levels of switching costs are less likely to induce service switching behavior [38]. Switching cost refers to the cost of converting one product or service to another of a competitor from a user’s point of view, and is composed of setup cost, sunk cost, and continuity cost [26,33]. In the transition from the traditional banks to an internet-only bank, it is expected that the sunk cost, which is the initial tangible and intangible cost for using new banking services, or the sunk cost that has already occurred, such as the investment cost for using the existing traditional bank, is insignificant. However, due to the transition to internet-only banking services, the cost of continuity giving up various benefits, such as low-interest rates and fee exemptions, as the main customer of a previous traditional bank, is expected to be high. Therefore, the following hypothesis is established:

Hypothesis 13.

The switching cost for incumbent internet banking negatively affects the intention to switch to internet-only banks.

3.4.2. Low IT Innovativeness

Although IT innovativeness is rarely used in switching behavior studies, it has been argued and confirmed as an individual trait that individual innovation influences the adoption of new technologies [59]. IT innovativeness refers to individuals’ willingness to actively try new information technologies. It has been known as an influential personal trait variable concerning technology innovation adoption behavior. Lu et al. [60] argued that individuals had more positive intentions for adopting IT innovation, as highly innovative individuals tend to take more risks. Conversely, if an individual’s IT innovativeness is low, it is inferred that he or she will have resistance to accepting new technologies or changes because they are less likely to take risks. Internet-only banking is a new technology that has brought significant changes in financial transactions. Those with low IT innovation are aware of the risk associated with changes in financial transactions and are therefore hesitate to switch to internet-only banks. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 14.

Low IT innovativeness negatively affects the intention to switch to internet-only banks.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

The data collection of this study was conducted for nearly 5 months from March 2020 to July 2020 targeting Kakao Bank, a Korean internet-only bank, in Mokpo, a small city in Korea. Data for empirical analysis of the research model were collected through a web-based online survey using a messenger link and a QR code provided by a cloud-based social science research automation site (ssra.or.kr). Since most people today have experience using internet banking, the respondents for data collection were randomly selected from university students and the public on campuses and on the streets. A total of 275 questionnaires were collected and used for empirical analysis of the research model. About 61% of respondents were male and 39% were female; 80% of respondents were over 30 years old and over 40% were workers. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for respondents.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of respondents’ characteristics.

4.2. Measurement Development

The measurements for this study were taken or modified from items that have been assured for reliability and validity in previous studies in order to increase the face validity of the constructs. The measurements for the low system quality, low information quality, and low service quality, which are constructs of push factors, were adapted from Tam and Oliveira [14]. The measurements for dissatisfaction and operation policy were adapted from Fei and Bo [42]. The measurements for switching cost and low IT innovativeness of the mooring factors were adapted from Lin and Huang [28] and Yoon et al. [59], respectively. The measurements for the perceived usefulness, compatibility, and peer influence of pull factors were adapted from Yoon et al. [59], Tan and Teo [20], and Cheng et al. [48], respectively. The measurements for the low cost of pull factors were new in this study. All measurement items employed a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). The measurements for this study are presented in the Appendix A.

5. Results

The partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique was employed to analyze the research model. PLS-SEM is known to be advantageous in analyzing complex research models [61] and has high statistical power [62] compared to the covariance-based SEM. Since the research model in this study is relatively large and composed of many constructs, we chose the PLS-SEM technique. For PLS-SEM analysis, this study used the PLS-PM package of the open-source software R [63].

5.1. Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Items

To evaluate the reliability and the validity of the measurement items for the constructs in the research model, internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity tests were performed. First, we evaluated the composite reliability (CR) value for the constructs in order to test internal consistency. In general, more than 0.7 of CR implies that each construct has an internal consistency of the measurement items [64]. Table 3 shows that the CR values of all constructs was much higher than 0.70. Thus, the results indicated the reliability of all measurement items for the construct.

Table 3.

Reliability.

Second, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using PLS-SEM in order to test the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs in the research model. In the convergent validity testing using the CFA, convergent validity is verified when the measurement items load significantly (t > 1.96) on their assigned construct [65] and when the average variance extracted (AVE) of the constructs is higher than 0.50 [66]. As shown in Table 4, the smallest t-value among the measurement items is 12.16, and all t-values are well over 1.96, and the AVE values of all constructs in Table 3 also far exceed the recommended value of 0.5. The results show convergent validity for all constructs.

Table 4.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

In the discriminant validity testing using the CFA, discriminant validity is verified when the value of correlations between constructs is less than the square root of the AVEs of their constructs [65,66]. As shown in Table 5, all correlation values between the constructs are less than the square root of the AVEs of their constructs. Therefore, the results show the discriminant validity of all constructs.

Table 5.

Average Variance Extracted and Correlation Matrix.

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

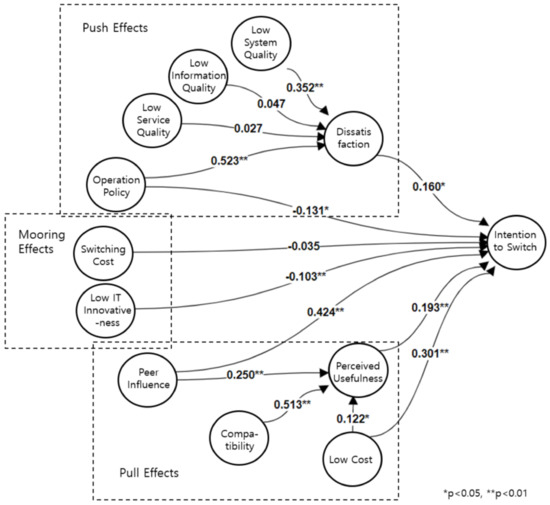

The hypothesis testing was performed based on the structural model produced after path analysis using PLS-SEM for the research model. Figure 2 shows the structural model including the path coefficients of the constructs and their significance.

Figure 2.

Path diagram of the research model.

In the structural model, the results showed that low system quality and operation policy significantly affected dissatisfaction, and in turn significantly affected the intention to switch, with α = 0.01; H1, H2, and H5 were therefore supported. Although the operational policy was shown to have a significant impact on the intention to switch, H6 was rejected due to a positive effect that was different from the hypothesis. In addition, low cost, compatibility, and peer influences significantly affected perceived usefulness, with α = 0.05 and α = 0.01, respectively; in turn, perceived usefulness, peer influences, and low cost significantly affected the intention to switch, with α = 0.01. H7, H8, H9, H10, H11, and H12 were therefore supported. Lastly, low IT innovativeness significantly affected the intention to switch, with α = 0.01; thus, H14 was supported. However, switching cost did not have a significant effect on the intention to switch; thus, H13 was rejected.

Table 6 shows the path coefficients, their t-values, and p-values on the hypotheses established in this study in detail. It also shows the coefficient of determination (R2) for each dependent construct.

Table 6.

Hypothesis testing results.

6. Discussion and Contributions

The results of the hypothesis testing showed that low system quality and operation policy influenced dissatisfaction, which in turn influenced customers’ intention to switch to internet-only banking. In addition, peer influence, low cost, and compatibility influenced perceived usefulness, resulting in customers’ intention to switch to internet-only banking. Low IT innovativeness, a mooring factor, influenced the intention to switch to internet-only banking. However, switching cost did not appear to affect customers’ intention to switch to internet-only banking.

As expected, dissatisfaction with incumbent internet banking was found to have a positive effect on switching to internet-only banking. In addition, the low system quality of incumbent internet banking and dissatisfaction with the operation policy was found to have a positive effect on dissatisfaction with internet banking. However, it was found that low information quality and low service quality of incumbent internet banking had no effect on dissatisfaction with internet banking. The study conducted by Tam and Oliveira [54], on mobile banking based on D&M models, the quality of information and quality of service, as well as the quality of the system, affected user satisfaction. However, this study, which was set as dissatisfaction, showed different results. These results can be explained by Frederick Herzberg’s two-factor theory that the motivators or factors affecting job satisfaction and the hygiene factors or the factors affecting job dissatisfaction are different. The results of the information system factors for dissatisfaction with this study might be found in the nature of internet banking. Internet banking is a system with a strong functional aspect that supports financial transactions, while the function of providing the information is relatively inadequate. In addition, with increasing advancements in internet banking technology, inquiries about how to use internet banking and system errors are decreasing and dependence on services is lowered; thus, low service quality does not seem to affect dissatisfaction.

In the results regarding the pull factors, peer influence was found to have the greatest influence on switching to internet-only banking (with a path coefficient of 0.424). As internet-only banks induce financial transactions using messenger, recent technology and interactive technology, peer influence, and social influence seem to have the most important influence on users’ switching to internet-only banks. As expected, the perceived usefulness was found to have a positive effect on the intention to switch. Perceived usefulness, a key variable of TAM, has been verified as an important factor in accepting various new technologies in the information system literature. For customers, internet-only banks are perceived as new information technology, and the perceived usefulness seems to have affected customers’ switching to internet-only banks. In addition, low cost, which is an important factor in service switching, was also shown to have a positive effect on the intent to switch. In addition, as expected, low cost, compatibility, and peer influence were shown to play an important role in shaping the perceived usefulness of internet-only banking.

In the results regarding the mooring factors, low IT innovativeness was found to have a negative effect on the intention of switching, similar to those in previous studies. However, unlike the results found by previous studies [28,32,38], switching cost did not have a significant effect on the intention to switch, suggesting that users have no financial or mental difficulties in transition from traditional internet banking to internet-only banking.

6.1. Contributions and Implications

This study has important academic and practical implications. First, it contributes to internet-only banking literature. Internet banking is a popular topic and many research studies have been conducted, but little is known about internet-only banks based on the latest fintech technologies. As an early work on internet-only banks, this study is expected to inspire further research. Second, this study developed and empirically analyzed a research model based on the PPM model in terms of switching, rather than the TAM or the DOI, which have often been used as a theoretical basis for the adoption of internet banking. The results showed that the predicted rate of the intention to switch was as high as 72%. These results demonstrate the theoretical contribution of this study as we have shown that PPM models can be used as a theoretical framework in internet-only banking acceptance research for customers. In addition, the research model is expected to be able to be used in research to analyze the churn of traditional bank customers. Third, this study focused on the fact that internet-only banks use interactive technology, and found that peer influence, which was not used in existing internet banking studies, had a great influence on conversion to internet-only banks. This result can be used as an important factor when constructing a model in subsequent studies related to internet-only banks.

This study provides not only the theoretical contributions described above, but also the following implications for practitioners. First, the study found that peer influence had a significant impact on the increased usefulness and intention to switch to internet-only banking. These results suggest that to effectively attract internet-only banking customers, system administrators need to develop effective financial transaction functions that can interact with customers. Second, the study found that low IT innovativeness had a negative impact on the intention to switch to a new information system. To reduce the negative impact of low IT innovativeness, managers of the internet-only banks should conduct intensive marketing on customers with high personal innovation for more effective customer acquisition. Lastly, dissatisfaction with the information system is an important factor that should be effectively managed for successful operation. This study proved that dissatisfaction with the incumbent internet banking had a significant impact on the intention to switch to internet-only banking. As the results of this study showed that the low system of internet banking and operation policy affected dissatisfaction, internet banking managers need to keep these results in mind.

6.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Although this study has several implications for researchers and practitioners, it has some limitations. First, the sample size for the empirical analysis in this study is rather small. Hence, it is important to identify powerful datasets and ensure that the data represent a diverse banking environment to assist future researchers in contributing more to this area. Second, this study used a survey method for the empirical analysis. In the future, combining in-depth interviewing techniques with bank customers is required to produce prescriptive and actionable results that can provide both theoretical and practical contributions. Third, since this study was conducted only in Korea with a high level of IT technology, the results may be different in other countries. Therefore, to generalize the research results, future research needs to be repeated in other countries. Fourth, this study was unable to perform various descriptive statistical analyzes on demographic variables, such as gender and age, in the process of accepting internet-only banks due to a lack of preparation for research design for descriptive statistical analysis. These descriptive statistical analyses can provide unexpected and interesting results. Therefore, future research needs to provide diverse and meaningful results with a research design for more detailed technical statistics. Fifth, other factors such as trust, perceived enjoyment, perceived risk, and culture, in addition to the variables of this research model, can influence customer adoption of internet-only banks. Future research needs to include these factors to better understand customers’ adoption of internet-only banks. Finally, the expansion of financial services by consumers from traditional banks of a new type of internet-only bank does not simply mean a change in the environment. Therefore, it is necessary for follow-up studies to conduct more systematic research design and in-depth analysis, and to present clear implications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y.; methodology, C.Y.; validation, C.Y.; formal analysis, C.Y. and D.L.; investigation, C.Y. and D.L.; simulation, C.Y.; writing— original draft preparation, C.Y.; writing—review and editing, D.L.; visualization, C.Y.; project administration, D.L.; funding acquisition, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be obtained through the website. Please see the text for details.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

- Low System Quality: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- There is an inconvenience in processing transactions using incumbent mobile banking.

- Incumbent mobile banking does not provide enough functionality to handle the business.

- Overall, the functionality level of incumbent mobile banking is low.

- Low Information Quality: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 4.

- The information provided by incumbent mobile banking is less useful.

- 5.

- The information provided by incumbent mobile banking is not interesting.

- 6.

- The completeness of the information provided by incumbent mobile banking is low.

- Low Service Quality: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 7.

- Availing services from incumbent mobile banking service centers is not easy.

- 8.

- Incumbent mobile banking service centers do not provide sufficient service.

- 9.

- Overall, the service quality of incumbent mobile banking service centers is low.

- Operation Policy: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 10.

- The operational policy of incumbent mobile banking is not reasonable.

- 11.

- I am somewhat dissatisfied with incumbent mobile banking management policies.

- Dissatisfaction: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 12.

- I am dissatisfied with incumbent mobile banking.

- 13.

- Overall, my satisfaction with incumbent mobile banking is low.

- Low Cost: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 14.

- Kakao Bank has a low transaction fee.

- 15.

- Kakao Bank has lower interest rates for loans.

- 16.

- I think it is economical to use Kakao Bank.

- Compatibility: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 17.

- Kakao Bank is compatible with my lifestyle.

- 18.

- Kakao Bank is suitable for my financial management method.

- 19.

- Kakao Bank fits perfectly into my financial business style.

- Peer Influence: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 20.

- My colleagues and friends think that I should use Kakao Bank.

- 21.

- People I know think that using Kakao Bank is better.

- Perceived Usefulness: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 22.

- Using Kakao Bank is effective for financial transactions.

- 23.

- Using Kakao Bank is useful for my financial transactions.

- Switching Cost: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 24.

- Overall, I will need a lot of time and effort to sign up for a new internet-only bank and use it.

- 25.

- In general, I will take a lot of time and effort to switch from current mobile banking to internet-only banking.

- Low IT Innovativeness: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 26.

- Among my peers, I am usually late in using new information technologies.

- 27.

- I don’t like to experiment with new information technologies.

- 28.

- Overall, I have a low interest in new information technologies.

- Intention to Switch: Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

- 29.

- I plan to primarily use Kakao Bank soon.

- 30.

- I will try to use Kakao Bank as much as possible.

References

- Chen, K.C. Implications of Fintech Developments for Traditional Banks. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2020, 10, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teka, B.M. Factors affecting bank customers usage of electronic banking in Ethiopia: Application of structural equation modeling (SEM). Cogent Econ. Financ. 2020, 8, 1762285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.J.; Lee, S.H. The effect of consumers’ perceived value on acceptance of an internet-only bank service. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoon, C.; Lim, D. An empirical study on factors affecting customers’ acceptance of internet-only banks in Korea. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1792259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, H.C. Processes of opinion change. Public Opin. Q. 1961, 25, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koo, C.; Wati, Y.; Chung, N. A study of mobile and internet banking service: Applying for IS success model. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 23, 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Goodhue, D.L.; Thompson, R.L. Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.; Oliveira, T. Performance impact of mobile banking: Using the task-technology fit (TTF) approach. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, W.C. Users’ adoption of e-banking services: The Malaysian perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2008, 23, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjaluoto, H.; Püschel, J.; Mazzon, J.A.; Hernandez, J.M.C. Mobile banking: Proposition of an integrated adoption intention framework. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2010, 28, 389–409. [Google Scholar]

- Marakarkandy, B.; Yajnik, N.; Dasgupta, C. Enabling internet banking adoption. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2017, 30, 263–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, H.A.; Al-Zubi, A.I. Determinants of internet banking adoption among customers of commercial banks: An empirical study in the Jordanian banking sector. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, A.A.; Ayo, C.K. An empirical investigation of the level of users’ acceptance of e-banking in Nigeria. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2010, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Teo, T.S. Factors influencing the adoption of Internet banking. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santouridis, I.; Kyritsi, M. Investigating the determinants of internet banking adoption in Greece. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 9, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zolait, A.H.S.; Sulaiman, A. The influence of communication channels on internet banking adoption. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2009, 2, 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, A.Y.L.; Ooi, K.B.; Lin, B.; Tan, B.I. Online banking adoption: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2010, 28, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moon, B. Paradigms in migration research: Exploring ‘moorings’ as a schema. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1995, 19, 504–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenstein, E.G. The laws of migration. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1889, 52, 241–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H.S.; Taylor, S.F.; St James, Y. “Migrating” to new service providers: Toward a unifying framework of consumers’ switching behaviors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.R. Understanding career commitment of IT professionals: Perspectives of push–pull–mooring framework and investment model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Huang, S.L. Understanding the determinants of consumers’ switching intentions in a standards war. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2014, 19, 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.C.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Roan, J.; Tseng, K.J.; Hsieh, J.K. The challenge for multichannel services: Cross-channel free-riding behavior. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2011, 10, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.C.; Liu, C.C.; Chen, K. The push, pull and mooring effects in virtual migration for social networking sites. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.K.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Chiu, H.C.; Feng, Y.C. Post-adoption switching behavior for online service substitutes: A perspective of the push–pull–mooring framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1912–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, S.; Wu, X.; Shen, X.L.; Zhang, X. Understanding users’ switching behavior of mobile instant messaging applications: An empirical study from the perspective of push-pull-mooring framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengyan, C.; Yinping, Y.; Lim, J. Cyber migration: An empirical investigation on factors that affect users’ switch intentions in social networking sites. In Proceedings of the 2009 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2009; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.Z.; Lee, M.K.; Cheung, C.M.; Chen, H. Understanding the role of gender in bloggers’ switching behavior. Decis. Support Syst. 2009, 47, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, A.C.; Chern, C.C.; Chen, H.G.; Chen, Y.C. ‘Migrating to a new virtual world’: Exploring MMORPG switching through human migration theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Potter, R. The role of habit in post-adoption switching of personal information technologies: An empirical investigation. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2011, 28, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.Y.; Debbarma, S.; Ulhas, K.R. An empirical study of consumer switching behaviour towards mobile shopping: A Push–Pull–Mooring model. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2012, 10, 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z.; Cheung, C.M.; Lee, M.K. Online service switching behavior: The case of blog service providers. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Q. Understanding Post Adoption Switching Behavior for Mobile Instant Messaging Application in China: Based on Migration Theory. In Proceedings of the 19th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Chengdu, China, 24–28 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, A.C.; Shang, R.A.; Huang, C.C.; Wu, K.L. The effects of Push-pull-mooring on the Switching Model for Social Network sites Migration. In Proceedings of the 19th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Chengdu, China, 24–28 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Park, S.C. Why end-users move to the cloud: A migration-theoretic analysis. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.; Bo, X. Do I switch? Understanding users’ intention to switch between social network sites. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 551–560. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.Y.; Wang, J. Switching attitudes of Taiwanese middle-aged and elderly patients toward cloud healthcare services: An exploratory study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 92, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. Examining user switch between mobile stores: A push-pull-mooring perspective. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. (IRMJ) 2016, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Wong, K.H.; Li, S.Y. Applying push-pull-mooring to investigate channel switching behaviors: M-shopping self-efficacy and switching costs as moderators. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2017, 24, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Vassileva, J.; Zhao, Y. Understanding users’ intention to switch personal cloud storage services: Evidence from the Chinese market. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.H.; Tang, K. Involuntary migration in cyberspaces: The case of MSN messenger discontinuation. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Lee, S.J.; Choi, B. An empirical investigation of users’ voluntary switching intention for mobile personal cloud storage services based on the push-pull-mooring framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, M.J.; Choi, J.S. Empirical Study on the Factors Affecting Individuals’ Switching Intention to Augmented/Virtual Reality Content Services Based on Push-Pull-Mooring Theory. Information 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, Z.; Chen, L. An empirical study of brand microblog users’ unfollowing motivations: The perspective of push-pull-mooring model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. Understanding Users’ Switching Between Social Media Platforms: A PPM Perspective. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Serv. Sect. (IJISSS) 2021, 13, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Limayem, M.; Cheung, C.M. User switching of information technology: A theoretical synthesis and empirical test. Inf. Manag. 2012, 49, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, C.; Kim, S. Developing the causal model of online store success. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2009, 19, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.; Oliveira, T. Understanding mobile banking individual performance. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 538–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveney, S.M. Customer switching behavior in service industries: An exploratory study. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Wang, Y.S.; Yang, Y.F. Understanding the determinants of RFID adoption in the manufacturing industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.Y.; Ku, C.Y.; Chang, C.M. Critical factors of WAP services adoption: An empirical study. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2003, 2, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.; Jeong, C.; Rolland, E. Understanding individual adoption of mobile instant messaging: A multiple perspectives approach. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2015, 16, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yao, J.E.; Yu, C.S. Personal innovativeness, social influences and adoption of wireless Internet services via mobile technology. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2005, 14, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Liang, H.; Xue, Y. Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: A principal-agent perspective. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, G.; Trinchera, L.; Russolillo, G. plspm: Tools for Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM); R package version 0.4. Available online: https://rdrr.io/cran/plspm/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).