The Diffusion Mechanism of Megaproject Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Institutional Isomorphism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Institutional Isomorphism: The Influence of Institutional Elements on Organizational Behavior

2.2. Megaproject Citizenship Behavior

2.3. The Diffusion of MCB under Institutional Isomorphism

2.4. The Effect of Megaproject Context

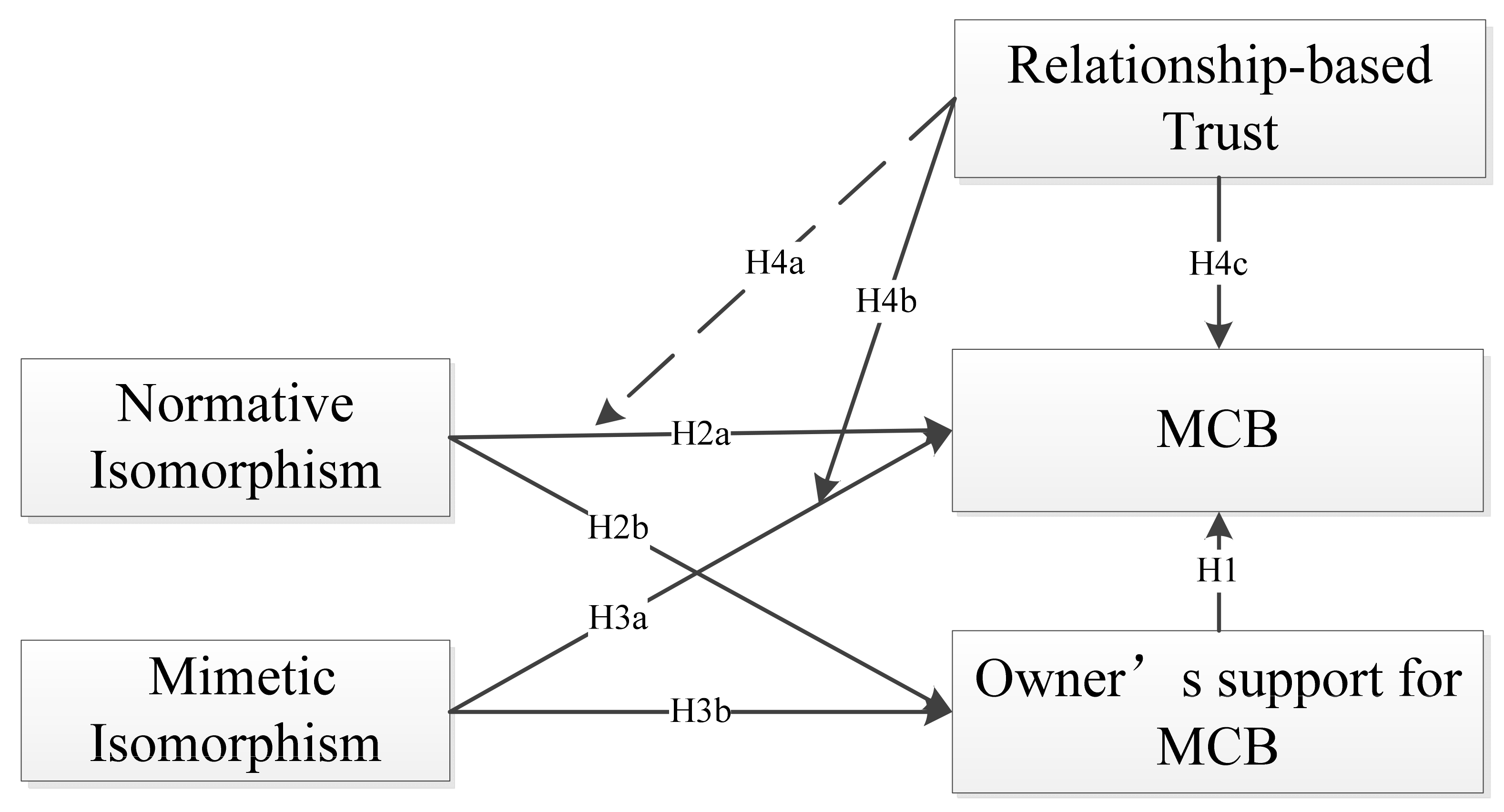

3. Research Hypothesis

3.1. The Effect of Project Owners’ Support on MCB’s Diffusion

3.2. The Effect of Institutional Isomorphism on MCB and Owners’ Support

3.2.1. Normative Isomorphism

3.2.2. Mimetic Isomorphism

3.3. The Effect of Relationship-Based Trust on the Diffusion of MCB Driven by Institutional Isomorphism

4. Research Method

5. Results

5.1. Structural Model Evaluation Results

5.2. Mediation Analysis

5.3. Moderation Analysis

6. Findings and Discussion

6.1. Promoting MCB through Normative Isomorphism

6.2. Promoting MCB through Mimetic Isomorphism

6.3. The Impact of Relationship-Based Trust in Promoting MCB through Normative Isomorphism

7. Conclusions and Implications

Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, Q.; Wang, T.; Chan, A.P.; Xu, J. Developing a List of Key Performance Indictors for Benchmarking the Success of Construction Megaprojects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04020164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; He, Q.; Cui, Q.; Hsu, S.C. Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Construction Megaprojects. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetemi, E.; Gemuenden, H.G.; Ordieres-Meré, J. Embeddedness and actors’ behaviors in large-scale project lifecycle: Lessons learned from a High-Speed Rail project in Spain. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 05020014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, Y.; Gao, J.; Shang, K.; Gao, S.; Xing, J.; Ni, G.; Yuan, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Mi, L. How the COVID-19 Outbreak Affected Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Emergency Construction Megaprojects: Case Study from Two Emergency Hospital Projects in Wuhan, China. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Kirkman, B.L.; Porter, C.O. Toward a model of work team altruism. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; He, Q.; Cui, Q.; Hsu, S.C. Non-economic motivations for organizational citizenship behavior in construction megaprojects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2020, 38, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Chen, K.; Zhang, M. Ultra-rapid delivery of specialty field hospitals to combat COVID-19: Lessons learned from the Leishenshan Hospital project in Wuhan. Autom. Constr. 2020, 119, 103345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, S.; Lin, H.; Tam, V.W.Y. Does megaproject social responsibility improve the sustainability of the construction industry? Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 27, 975–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninan, J.; Clegg, S.; Mahalingam, A. Branding and governmentality for infrastructure megaprojects: The role of social media. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesenthal, C.; Clegg, S.; Mahalingam, A.; Sankaran, S. Applying institutional theories to managing megaprojects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Ende, L.V.; Van Marrewijk, A. Teargas, taboo and transformation: A neo-institutional study of community resistance and the struggle to legitimize subway projects in Amsterdam 1960–2018. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuganesan, S.; Floris, M. Investigating perspective taking when infrastructure megaproject teams engage local communities: Navigating tensions and balancing perspectives. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2020, 38, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. The institutional environment of global project organizations. Eng. Proj. Organ. J. 2012, 2, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, J.; Sydow, J. Projects and institutions: Towards understanding their mutual constitution and dynamics. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Cui, Q.; Han, Y. Organizational behavior in megaprojects: Integrative review and directions for future research. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 04019009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Chen, H.; Sheng, Z.; Cheng, S. Governance of institutional complexity in megaproject organizations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.S.F.; Javernick-Will, A.M. Institutional effects on project arrangement: High-speed rail projects in China and Taiwan. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnen, M. Institutional development, divergence and change in the discipline of project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, N.; Stafford, A.; Musonda, I. Duality by Design: The Global Race to Build Africa’s Infrastructure; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Denicol, J.; Davies, A.; Krystallis, I. What Are the Causes and Cures of Poor Megaproject Performance? A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Proj. Manag. J. 2020, 51, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, G.; Mariani, G.; Sainati, T.; Greco, M. Corruption in public projects and megaprojects: There is an elephant in the room! Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daniel, E.; Daniel, P.A. Megaprojects as complex adaptive systems: The Hinkley point C case. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Turner, R.; Andersen, E.S.; Shao, J.; Kvalnes, Ø. Ethics, trust, and governance in temporary organizations. Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.Y.; Shen, G.Q.; Yang, J. Stakeholder management studies in mega construction projects: A review and future directions. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Sui, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, L.; Zeng, S. CEO narcissism, public concern, and megaproject social responsibility: Moderated mediating examination. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.J.; Scott, W.R.; Levitt, R.E.; Artto, K.; Kujala, J. Global Projects: Distinguishing Features, Drivers, and Challenges. In Global Projects: Institutional and Political Challenges; Scott, W.R., Levitt, R.E., Orr, R.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; Volume 43, pp. 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hosseini, M.R.; Banihashemi, S.; Martek, I.; Golizadeh, H.; Ghodoosi, F. Sustainable delivery of megaprojects in Iran: Integrated model of contextual factors. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zafar, I. Dynamic Stakeholder-Associated Topic Modeling on Public Concerns in Mega infrastructure Projects: Case of Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macao Bridge. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.Y.; Benbasat, I. Organizational buyers’ adoption and use of B2B electronic marketplaces: Efficiency-and legitimacy-oriented perspectives. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 55–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheung, S.O.; Wei, K.W.; Yiu, T.W.; Pang, H.Y. Developing a trust inventory for construction contracting. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2011, 29, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C.F. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flyvbjerg, B. The Oxford Handbook of Megaproject Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Da, P.; Zhang, Y. Organizational network evolution and governance strategies in megaprojects. Constr. Econ. Build. 2015, 15, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leung, K. Theorizing about Chinese organizational behavior: The role of cultural and social forces. In Handbook of Chinese Organizational Behavior: Integrating Theory, Research and Practice; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Galaskiewicz, J.; Wasserman, S. Mimetic Processes Within an Interorganizational Field: An Empirical Test. Adm. Sci. Q. 1989, 34, 454–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winch, G.; Leiringer, R. Owner project capabilities for infrastructure development: A review and development of the “strong owner” concept. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boateng, P.; Chen, Z.; Ogunlana, S.O. An analytical network process model for risks prioritisation in megaprojects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1795–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, P. Owner organization design for mega industrial construction projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2011, 29, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, J.; Peltokorpi, A.; Artto, K. Megaprojects as organizational platforms and technology platforms for value creation. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chan, A.P.; Le, Y. Understanding the determinants of program organization for construction megaproject success: Case study of the shanghai expo construction. J. Manag. Eng. 2014, 31, 05014019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Shen, L.; Xia, B.; Li, B. Key attributes underpinning different markup decision between public and private projects: A China study. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eweje, J.; Turner, R.; Müller, R. Maximizing strategic value from megaprojects: The influence of information-feed on decision-making by the project manager. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2012, 30, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanderson, J.; Winch, G. Public policy and projects: Making connections and starting conversations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvuur, A.M.; Kumaraswamy, M.M. Effects of Teamwork Climate on Cooperation in Crossfunctional Temporary Multi-Organization Workgroups. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04015054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shim, D.C.; Faerman, S. Government employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: The impacts of public service motivation, organizational identification, and subjective OCB norms. Int. Public Manag. J. 2015, 20, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Olsen, J.P. Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.; Wan, J.B.; Zhang, R. Discussion on Successful Practices and Experience of Working Competition on the South-to-North Water Transfer Project. South-to-North Water Transf. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 11, 174–176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Love, P.E.D.; Ahiaga-Dagbui, D.D. Debunking fake news in a post-truth era: The plausible untruths of cost underestimation in transport infrastructure projects. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 113, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giezen, M.; Bertolini, L.; Salet, W. Adding value to the decision-making process of megaprojects: Fostering strategic ambiguity, redundancy, and resilience. Transp. Policy 2015, 44, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heere, N.; Xing, X. BOCOG’s road to success: Predictors of commitment to organizational success among Beijing Olympic employees. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2012, 12, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Chen, Y.; You, J.; Yao, H. Asset Specificity and Contractors’ Opportunistic Behavior: Moderating Roles of Contract and Trust. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Skitmore, M.; Yan, L. How contractor behavior affects engineering project value-added performance. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 04019012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, L.H.; Ho, Y.L. Guanxi and OCB: The Chinese cases. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddednes. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Toward a Structural Theory of Action: Network Models of Social Structure, Perception and Action; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, H.H.; Wei, K.K.; Benbasat, I. Predicting Intention to Adopt Interorganizational Linkages: An Institutional Perspective. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 19–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powell, W.P.; Bromley, P. New Institutionalism in the Analysis of Complex Organizations. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 101, 764–769. [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay, S. Non-Contractual Relations in Business: A Preliminary Study. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1963, 28, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Maynes, T.D.; Spoelma, T.M. Consequences of unit-level organizational citizenship behaviors: A review and recommendations for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35 (Suppl. 1), S87–S119. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, J. What leads to post-implementation success of ERP? An empirical study of the Chinese retail industry. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Andersen, E.S.; Kvalnes, Ø.; Shao, J.; Sankaran, S.; Turner, R.; Biesenthal, C.; Walker, D.; Gudergan, S. The interrelationship of governance, trust, and ethics in temporary organizations. Proj. Manag. J. 2013, 44, 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bommer, W.H.; Dierdorff, E.C.; Rubin, R.S. Does prevalence mitigate relevance? The moderating effect of group-level OCB on employee performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1481–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.G.; Carroll, S.J.; Ashford, S.J. Intra- and interorganizational cooperation: Toward a research agenda. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Lomax, R.G. An Introduction to Statistical Concepts, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Du, J.; Worthy, D.A. The impact of engineering information formats on learning and execution of construction operations: A virtual reality pipe maintenance experiment. Autom. Constr. 2020, 119, 103367. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Ling, F.Y.Y. Reducing hindrances to adoption of relational behaviors in public construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 04013017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninan, J.; Mahalingam, A.; Clegg, S. External Stakeholder Management Strategies and Resources in Megaprojects: An Organizational Power Perspective. Proj. Manag. J. 2019, 50, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, Z.H.; Lechler, T.G. Contributing beyond the call of duty: Examining the role of culture in fostering citizenship behavior and success in project-based work. RD Manag. 2009, 39, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R.; Baker, W.; Parker, A. What creates energy in organizations? MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Winch, G. Megaproject Stakeholder Management. In The Oxford Handbook of Megaproject Management; Flyvbjerg, B., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Code | Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project Compliance (PC) | PC1 | We obey project task arrangements of our own accord | 0.848 |

| PC2 | We abide project management requirements of our own accord | 0.904 | |

| PC3 | We voluntarily obey project goals | 0.871 | |

| PC4 | We strictly obey government’s project requirements | 0.770 | |

| Contingent Collaboration (CCL) | CCL2 | We remind other participants of possible mistakes out of goodwill | 0.707 |

| CCL3 | We assist other participants to solve construction related difficulties (e.g., lending equipment) | 0.785 | |

| CCL4 | We share project experiences with other participants | 0.818 | |

| CCL5 | We facilitate other participants in both upper and lower working processes and interfaces | 0.808 | |

| CCL6 | We proactively resolve conflicts with other participants | 0.794 | |

| Conscientiousness (CB) | CB2 | We strive for perfection, even under no supervision | 0.794 |

| CB3 | We consciously distribute sufficient resources (manpower, money, material) for the project | 0.880 | |

| CB4 | We join or organize team training of our own accord | 0.853 | |

| CB5 | We join and assist activities and meetings organized by project organization of our own accord | 0.789 | |

| Harmonious Relationship Maintenance (HRM) | HRM1 | We proactively build a harmonious relationship with the related government officials | 0.887 |

| HRM2 | We proactively build a harmonious relationship with the stakeholders (e.g., residents affected by the project, local government, etc.) | 0.697 | |

| HRM3 | We do not care about the past grudges and conflicts with other participants for the sake of the project | 0.833 | |

| Initiative Behavior (IB) | IB1 | We provided innovative ideas to improve the project | 0.625 |

| IB2 | We proactively applied advanced technologies (e.g., BIM, green building, etc.) | 0.762 | |

| IB3 | We pointed out potential improvements of project management | 0.855 | |

| IB4 | We voluntarily make constructive suggestions on project implementation | 0.760 | |

| Normative Isomorphic (NI) | NI1 | Media actively propagate the major contributions of megaproject participants | 0.889 |

| NI 2 | Management units (e.g., labor unions, project coordination office, etc.) organize or promote merit competition and other activities that encourage OCB | 0.905 | |

| NI3 * | Construction mode of megaprojects are in general beyond conventional and already turned into customary practice | 0.262 | |

| Mimetic Isomorphic (MI) | MI1 | Other megaprojects achieved a satisfactory result through OCB encouraging activities (e.g., merit competitions) | 0.911 |

| MI2 | Other megaprojects achieved positive social impact through enhancing participants’ OCB | 0.950 | |

| MI3 | OCB of other megaproject participants received the deserved rewards and acclaim | 0.927 | |

| Relationship-based Trust (TR) | TR1 | Based on our relationship, we believe the other party (participants who are of vital interest to us, same as below) handles things in a fair manner | 0.837 |

| TR2 | Based on our relationship, we believe the other party holds fast to morality | 0.833 | |

| TR3 | Based on our relationship, we believe the other party protects our interests | 0.891 | |

| TR4 | Based on our relationship, we believe the other party fulfills their promises | 0.921 | |

| TR5 | Based on our relationship, we believe the other party is honest | 0.927 | |

| TR6 | Based on our relationship, we believe the other party has professionalism | 0.861 | |

| TG7 | Based on our relationship, we believe the other party has dedication | 0.888 | |

| Owner’s Support (OS) | OS1 | The project has implemented several measures to promote the OCB of participants | 0.828 |

| OS2 | Promoting OCB is an important task to the project | 0.910 | |

| OS3 | The project provided supports for participants to develop OCB | 0.895 | |

| OS4 | The project confirms the value of participants’ OCB | 0.889 |

| Normalized Factor Loadings | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | CB | CCL | HGM | IB | MI | NI | PC | OS | TR | T-Value |

| CB2 | 0.7956 | 0.4924 | 0.4806 | 0.4575 | 0.2305 | 0.2734 | 0.3504 | 0.2624 | 0.2886 | 32.467 |

| CB3 | 0.8500 | 0.5018 | 0.5067 | 0.4264 | 0.1757 | 0.2825 | 0.3586 | 0.2478 | 0.2292 | 42.361 |

| CB4 | 0.8519 | 0.5039 | 0.5865 | 0.4952 | 0.2730 | 0.3328 | 0.3839 | 0.3042 | 0.3712 | 47.299 |

| CB5 | 0.7885 | 0.5349 | 0.5255 | 0.4670 | 0.2303 | 0.2816 | 0.3296 | 0.2358 | 0.1969 | 30.293 |

| CCL2 | 0.4544 | 0.7062 | 0.4275 | 0.3378 | 0.1779 | 0.2491 | 0.2701 | 0.2040 | 0.1843 | 18.297 |

| CCL3 | 0.4468 | 0.7863 | 0.4474 | 0.3961 | 0.2179 | 0.2499 | 0.3064 | 0.2506 | 0.2989 | 36.421 |

| CCL4 | 0.5155 | 0.8189 | 0.4157 | 0.4633 | 0.2344 | 0.2732 | 0.3801 | 0.3294 | 0.3500 | 38.114 |

| CCL5 | 0.4617 | 0.8066 | 0.3561 | 0.4174 | 0.1296 | 0.1745 | 0.3277 | 0.2298 | 0.2683 | 22.406 |

| CCL6 | 0.5387 | 0.7942 | 0.4419 | 0.3592 | 0.1871 | 0.2957 | 0.3775 | 0.3071 | 0.3059 | 33.066 |

| HRM1 | 0.5167 | 0.3959 | 0.8213 | 0.3891 | 0.1099 | 0.1721 | 0.2855 | 0.1602 | 0.1717 | 34.725 |

| HRM2 | 0.6152 | 0.4903 | 0.8875 | 0.4010 | 0.2332 | 0.3015 | 0.3309 | 0.2628 | 0.2774 | 67.447 |

| HRM3 | 0.4020 | 0.3999 | 0.7093 | 0.3740 | 0.0670 | 0.1385 | 0.2064 | 0.1438 | 0.2129 | 15.303 |

| IB1 | 0.3917 | 0.3544 | 0.2615 | 0.7498 | 0.2268 | 0.3019 | 0.2776 | 0.2629 | 0.1710 | 18.212 |

| IB2 | 0.4301 | 0.3812 | 0.4071 | 0.7653 | 0.3066 | 0.2506 | 0.2886 | 0.2895 | 0.2197 | 24.339 |

| IB3 | 0.4935 | 0.4551 | 0.4444 | 0.8859 | 0.3035 | 0.2585 | 0.2659 | 0.2829 | 0.2399 | 59.302 |

| IB4 | 0.5081 | 0.4487 | 0.4273 | 0.8581 | 0.2873 | 0.2941 | 0.2854 | 0.2857 | 0.1973 | 47.134 |

| MI1 | 0.2881 | 0.2383 | 0.1875 | 0.3098 | 0.6914 | 0.4523 | 0.2094 | 0.4218 | 0.3472 | 17.309 |

| MI2 | 0.3091 | 0.2271 | 0.1927 | 0.3293 | 0.7035 | 0.4162 | 0.2534 | 0.4557 | 0.3840 | 19.467 |

| MI3 | 0.2849 | 0.2223 | 0.1707 | 0.3223 | 0.6678 | 0.3875 | 0.2267 | 0.4201 | 0.3575 | 17.894 |

| NI1 | 0.3322 | 0.2670 | 0.2862 | 0.2945 | 0.3588 | 0.6583 | 0.2918 | 0.3439 | 0.3016 | 17.039 |

| NI2 | 0.3854 | 0.3023 | 0.2287 | 0.3048 | 0.4351 | 0.6495 | 0.2923 | 0.3950 | 0.3292 | 19.791 |

| PC1 | 0.4549 | 0.4306 | 0.4052 | 0.3517 | 0.1567 | 0.2103 | 0.8419 | 0.2195 | 0.2388 | 37.313 |

| PC2 | 0.5636 | 0.4312 | 0.3904 | 0.3934 | 0.1397 | 0.1987 | 0.9029 | 0.2087 | 0.1888 | 60.161 |

| PC3 | 0.5363 | 0.4870 | 0.3923 | 0.4249 | 0.1723 | 0.2286 | 0.8729 | 0.2470 | 0.1874 | 42.979 |

| PC4 | 0.4829 | 0.4252 | 0.4314 | 0.3678 | 0.1618 | 0.2045 | 0.7752 | 0.1985 | 0.2648 | 21.561 |

| OS1 | 0.2538 | 0.2676 | 0.1914 | 0.2307 | 0.3226 | 0.3299 | 0.2538 | 0.6006 | 0.3615 | 18.662 |

| OS2 | 0.3504 | 0.3308 | 0.2752 | 0.2899 | 0.4038 | 0.3806 | 0.3280 | 0.7034 | 0.4571 | 27.515 |

| OS3 | 0.2701 | 0.2569 | 0.1984 | 0.2827 | 0.3847 | 0.3174 | 0.2466 | 0.5520 | 0.3417 | 21.634 |

| OS4 | 0.3252 | 0.2858 | 0.2125 | 0.3310 | 0.4259 | 0.3564 | 0.2991 | 0.5890 | 0.3957 | 21.329 |

| TR1 | 0.2880 | 0.2640 | 0.2365 | 0.2014 | 0.3121 | 0.2844 | 0.2724 | 0.3844 | 0.5451 | 19.618 |

| TR2 | 0.3305 | 0.2966 | 0.2298 | 0.1965 | 0.2921 | 0.2932 | 0.3125 | 0.4081 | 0.5959 | 17.573 |

| TR3 | 0.3113 | 0.3415 | 0.2207 | 0.1960 | 0.3533 | 0.3315 | 0.3158 | 0.4707 | 0.7075 | 23.374 |

| TR4 | 0.3230 | 0.3472 | 0.2606 | 0.2117 | 0.3182 | 0.2932 | 0.3103 | 0.4265 | 0.6768 | 24.658 |

| TR5 | 0.3018 | 0.3007 | 0.2519 | 0.2194 | 0.3300 | 0.2987 | 0.2640 | 0.3700 | 0.6297 | 21.311 |

| TR6 | 0.3350 | 0.2976 | 0.3186 | 0.2255 | 0.3501 | 0.3074 | 0.2794 | 0.3533 | 0.5790 | 17.178 |

| TR7 | 0.4172 | 0.3967 | 0.3525 | 0.2867 | 0.4166 | 0.3663 | 0.3453 | 0.4680 | 0.7616 | 23.325 |

| Items | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s α | CB | CCL | HGM | IB | MI | NI | OS | PC | TR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB | 0.7442 | 0.8927 | 0.8410 | 0.8627 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CCL | 0.6748 | 0.8880 | 0.8438 | 0.6185 | 0.8214 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| HRM | 0.6678 | 0.8497 | 0.7256 | 0.6393 | 0.5328 | 0.8172 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| IB | 0.6706 | 0.8886 | 0.8439 | 0.5618 | 0.5052 | 0.4787 | 0.8189 | - | - | - | - | - |

| MI | 0.864 | 0.9501 | 0.9211 | 0.4310 | 0.3348 | 0.2814 | 0.4761 | 0.9295 | - | - | - | - |

| NI | 0.805 | 0.8919 | 0.7580 | 0.5530 | 0.4391 | 0.4068 | 0.4609 | 0.6088 | 0.8972 | - | - | - |

| OS | 0.7758 | 0.9326 | 0.9036 | 0.4928 | 0.4660 | 0.3648 | 0.4618 | 0.6130 | 0.5622 | 0.8808 | - | - |

| PC | 0.7277 | 0.9118 | 0.8536 | 0.6021 | 0.5231 | 0.4757 | 0.4542 | 0.3341 | 0.4463 | 0.4654 | 0.8531 | - |

| TR | 0.7753 | 0.9602 | 0.9514 | 0.4753 | 0.4918 | 0.3860 | 0.3336 | 0.5039 | 0.4582 | 0.6166 | 0.4321 | 0.8805 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, D.; Zhu, J.; Cui, Q.; He, Q.; Zheng, X. The Diffusion Mechanism of Megaproject Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Institutional Isomorphism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158123

Yang D, Zhu J, Cui Q, He Q, Zheng X. The Diffusion Mechanism of Megaproject Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Institutional Isomorphism. Sustainability. 2021; 13(15):8123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158123

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Delei, Jun Zhu, Qingbin Cui, Qinghua He, and Xian Zheng. 2021. "The Diffusion Mechanism of Megaproject Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Institutional Isomorphism" Sustainability 13, no. 15: 8123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158123

APA StyleYang, D., Zhu, J., Cui, Q., He, Q., & Zheng, X. (2021). The Diffusion Mechanism of Megaproject Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Institutional Isomorphism. Sustainability, 13(15), 8123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158123