The Influence of Media Usage on Iranian Students’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

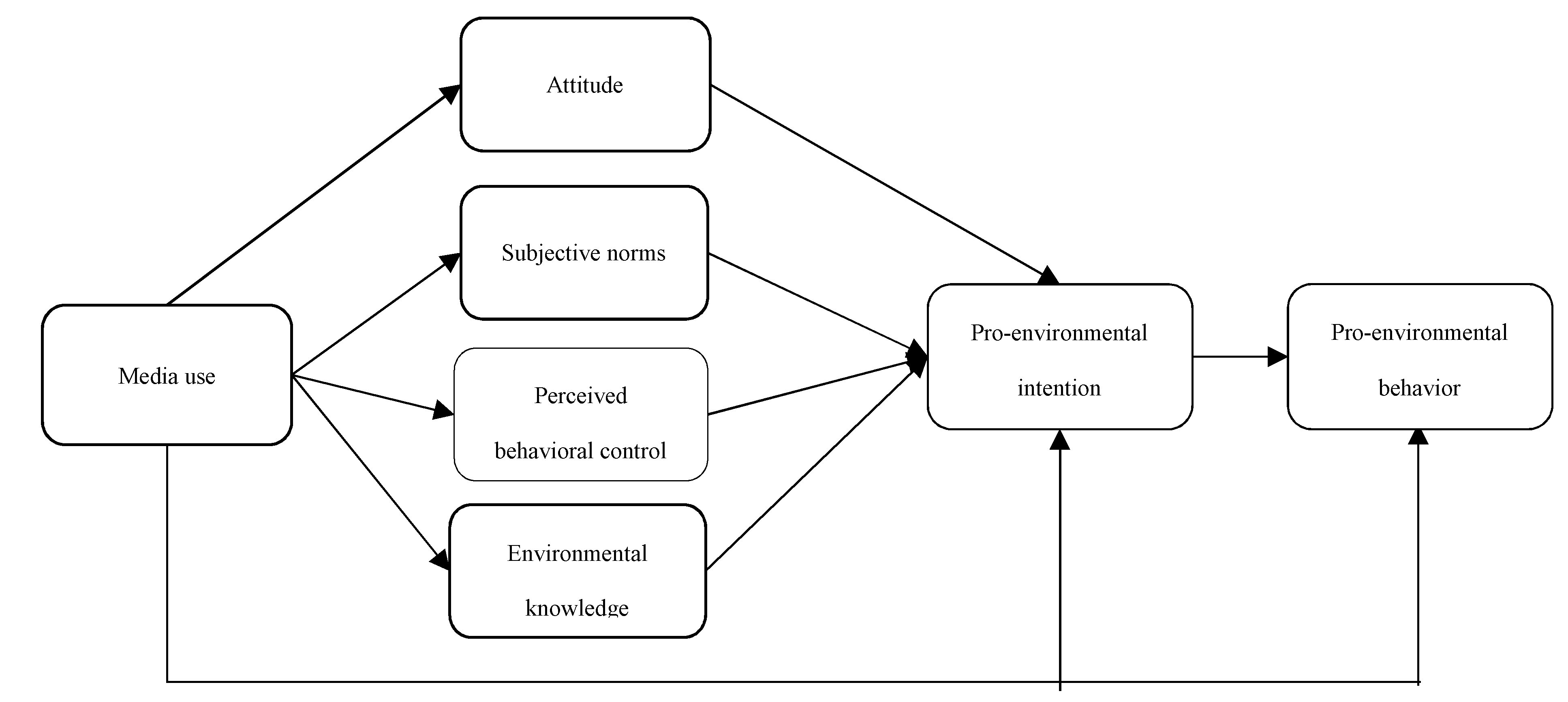

1.1. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

1.2. Inclusion of Environmental Knowledge in the TPB

1.3. Inclusion of Media Use in the TPB

1.4. Media Use and the TPB Constructs

1.5. Media Use and Environmental Knowledge

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Data Collection

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model Assessment

3.2. Structural Model Assessment

4. Discussions

5. Implications

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, G.A. Framing a model for green buying behavior of Indian consumers: From the lenses of the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeland, E.K.; Kettenring, K.M. Strategic plant choices can alleviate climate change impacts: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 222, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liutsko, L. The integrative model of personality and the role of personality in a Planetary Health context. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 151, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2020 Environmental Performance Index; Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy: New Haven, CT, USA. Available online: https://epi.yale.edu/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Karimi, S.; Saghaleini, A. Factors influencing ranchers’ intentions to conserve rangelands through an extended theory of planned behavior. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadeh, F. Environmental Awareness, Attitudes, and Behaviour of Secondary School Students and Teachers in Tehran, Iran. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2007, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D. The “Gateway Belief” illusion: Reanalyzing the results of a scientific-consensus messaging study. J. Sci. Commun. 2017, 16, A03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thondhlana, G.; Hlatshwayo, T.N. Pro-Environmental Behaviour in Student Residences at Rhodes University, South Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karimi, S. Pro-environmental behaviours among agricultural students: An examination of the value-belief-norm theory. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, T.-K. The Moderating Effects of Students’ Personality Traits on Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intentions in Response to Climate Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clayton, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Swim, J.K.; Bonnes, M.; Steg, L.; Whitmarsh, L.; Carrico, A. Expanding the role for psychology in addressing environmental challenges. Am. Psychol. 2016, 71, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asilsoy, B.; Oktay, D. Exploring environmental behaviour as the major determinant of ecological citizenship. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors?: The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. How do motives and knowledge relate to intention to perform environmental behavior? Assessing the mediating role of constraints. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergek, A.; Mignon, I. Motives to adopt renewable electricity technologies: Evidence from Sweden. Energy Policy 2017, 106, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.; Fernández-Sainz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Does gender make a difference in pro-environmental behavior? The case of the Basque Country University students. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi Moghaddam, M.; Maknoon, R.; Babazadeh Naseri, A.; Khanmohammadi Hazaveh, M.; Eftekhari Yegane, Y. Evaluation of Awareness, Attitude and Action of Amirkabir University of Technology Students on General Aspects of Environment. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 14, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Marzban, A.; Barzegaran, M.; Hemayatkhah, M.; Ayasi, M.; Delavari, S.; Sabzehei, M.; Rahmanian, V. Evaluation of environmental awareness and behavior of citizens (case study: Yazd urban population). Iran. J. Health Environ. 2019, 12, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pouratashi, M.; Zamani, A. University students’ level of knowledge, attitude and behavior toward sustainable development: A comparative study by GAMES. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikiene, G.; Mandravickaitė, J.; Bernatonienė, J. Theory of planned behavior approach to understand the green purchasing behavior in the EU: A cross-cultural study. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 125, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.; Bishop, B. A moral basis for recycling: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maki, A.; Rothman, A.J. Understanding proenvironmental intentions and behaviors: The importance of considering both the behavior setting and the type of behavior. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 157, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fielding, K.; McDonald, R.; Louis, W. Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Hua, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, G. Determinants of consumer’s intention to purchase authentic green furniture. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liang, J.; Qiang, Y.; Fang, S.; Gao, M.; Fan, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, B.; Feng, Y. Analysis of the environmental behavior of farmers for non-point source pollution control and management in a water source protection area in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.-G.; Tang, D.; Wu, G.; Lan, J. Understanding intention and behavior toward sustainable usage of bike sharing by extending the theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, G.; Ren, G.; Feng, Y. Analysis of the environmental behavior of farmers for non-point source pollution control and management: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M.S. The Importance of Environmental Knowledge for Private and Public Sphere Pro-Environmental Behavior: Modifying the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J.B.; Durfee, J.L. Testing Public (Un)Certainty of Science. Sci. Commun. 2004, 26, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballew, M.T.; Omoto, A.M.; Winter, P. Using Web 2.0 and Social Media Technologies to Foster Proenvironmental Action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10620–10648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H. Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.H.; Patel, J.; Acharya, N. Causality analysis of media influence on environmental attitude, intention and behaviors leading to green purchasing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Zhong, Z.-J. Extending media system dependency theory to informational media use and environmentalism: A cross-national study. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 50, 101378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.S.; Liao, Y.; Rosenthal, S. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior and Media Dependency Theory: Predictors of Public Pro-environmental Behavioral Intentions in Singapore. Environ. Commun. 2014, 9, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, H.-C.; Choong, W.-W.; Alwi, S.R.W.; Mohammed, A.H. Using Theory of Planned Behaviour to explore oil palm smallholder planters’ intention to supply oil palm residues. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Lans, T.; Mulder, M. Understanding the Role of Cultural Orientations in the Formation of Entrepreneurial Intentions in Iran. J. Career Dev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstreet, R.E.; Cegielski, C.; Hall, D. Predictors of the intent to adopt preventive innovations: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.D.; Stride, C. Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M. E-waste recycling behaviour: An integration of recycling habits into the theory of planned behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 124182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Exploring young adults’ e-waste recycling behaviour using an extended theory of planned behaviour model: A cross-cultural study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Long, X.; Li, L.; Liang, H.; Wang, Q.; Ding, X. Determinants of intention and behavior of low carbon commuting through bicycle-sharing in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The Explanatory and Predictive Scope of Self-Efficacy Theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zuo, J.; Cai, H.; Zillante, G. Construction waste reduction behavior of contractor employees: An extended theory of planned behavior model approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zha, L.; Liu, F.; He, L.; Sun, X.; Jing, X. Environmental awareness and pro-environmental behavior within China’s road freight transportation industry: Moderating role of perceived policy effectiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujata, M.; Khor, K.-S.; Ramayah, T.; Teoh, A.P. The role of social media on recycling behaviour. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 20, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoker, E.N.; Van Der Linden, S. Fleshing out the theory of planned of behavior: Meat consumption as an environmentally significant behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to predict Iranian students’ intention to purchase organic food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Yu, P.; Chu, G. What influences tourists’ intention to participate in the Zero Litter Initiative in mountainous tourism areas: A case study of Huangshan National Park, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.C. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate pur-chase intention of green products among Thai consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pothitou, M.; Hanna, R.F.; Chalvatzis, K. Environmental knowledge, pro-environmental behaviour and energy savings in households: An empirical study. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, N. Consistency and “awareness gaps” in the environmental behaviour of Hungarian companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, N.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryxell, G.E.; Lo, C.W.H. The Influence of Environmental Knowledge and Values on Managerial Behaviours on Behalf of the Environment: An Empirical Examination of Managers in China. J. Bus. Ethic 2003, 46, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.; Leonidou, C.N.; Kvasova, O. Antecedents and outcomes of consumer environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviour. J. Mark. Manag. 2010, 26, 1319–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernandez-Sainz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: Comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Han, C.; Teng, M. The influence of Internet use on pro-environmental behaviors: An integrated theoretical framework. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T.H.; Laverie, D.A.; Wilcox, J.F.; Duhan, D.F. Differential Effects of Experience, Subjective Knowledge, and Objective Knowledge on Sources of Information used in Consumer Wine Purchasing. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 29, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiaslis, A.; Krontalis, A.K. Green Consumption Behavior Antecedents: Environmental Concern, Knowledge, and Beliefs. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S. Do we know what we need to know? Objective and subjective knowledge effects on pro-ecological behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Aguilar, F.; Yang, J.; Qin, Y.; Wen, Y. Predicting citizens’ participatory behavior in urban green space governance: Application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M.E.; Shaw, D.L. The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media. Public Opin. Q. 1972, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, N.; Chao, N.; Wang, C. Predicting the Intention of Sustainable Commuting among Chinese Commuters: The Role of Media and Morality. Environ. Commun. 2020, 15, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A. Media(ted)discourses and climate change: A focus on political subjectivity and (dis)engagement. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Höijer, B. Emotional anchoring and objectification in the media reporting on climate change. Public Underst. Sci. 2010, 19, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masud, M.M.; Akhtar, R.; Afroz, R.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Kari, F.B. Pro-environmental behavior and public understanding of climate change. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2013, 20, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, L. The Role of Media System Development in the Emergence of Postmaterialist Values and Environmental Concern: A Cross-National Analysis. Soc. Sci. Q. 2012, 93, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, L.; Hutchins, B.; Lester, E. Power games: Environmental protest, news media and the internet. Media, Cult. Soc. 2009, 31, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, B.; Tandoc, E.; Duan, R.; Van Witsen, A. Revisiting Environmental Citizenship. Environ. Behav. 2016, 49, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.J.; Dunwoody, S.; Neuwirth, K. Proposed Model of the Relationship of Risk Information Seeking and Processing to the Development of Preventive Behaviors. Environ. Res. 1999, 80, S230–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K. The role of media exposure, social exposure and biospheric value orientation in the environmental attitude-intention-behavior model in adolescents. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Personal Values and Environmental Concern in China and the US: The Mediating Role of Informational Media Use. Commun. Monogr. 2012, 79, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelms, C.; Allen, M.W.; Craig, C.; Riggs, S. Who is the Adolescent Environmentalist? Environmental Attitudes, Identity, Media Usage and Communication Orientation. Environ. Commun. 2017, 11, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C.-L. The Influence of Mass Media and Interpersonal Communication on Societal and Personal Risk Judgments. Commun. Res. 1993, 20, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, T.A.; Duck, J.M. Communication and Health Beliefs. Commun. Res. 2001, 28, 602–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, M.; Wang, F.; Yu, N. Internet use encourages pro-environmental behavior: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, M. The Effects of Consumers’ Media Exposure, Attention, and Credibility on Pro-environmental Behaviors. J. Promot. Manag. 2019, 26, 434–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Role of Affective Mediators in the Effects of Media Use on Pro-environmental Behavior. Sci. Commun. 2020, 43, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Ho, S.S.; Yang, X. Motivators of Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sci. Commun. 2015, 38, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junsheng, H.; Akhtar, R.; Masud, M.M.; Rana, S.; Banna, H. The role of mass media in communicating climate science: An empirical evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbert, R.L.; Kwak, N.; Shah, D.V. Environmental Concern, Patterns of Television Viewing, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Integrating Models of Media Consumption and Effects. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2003, 47, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.K. Mass media and environmental knowledge of secondary school students in Hong Kong. Environmentalist 1998, 19, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.T.; Fok, L.; Tsang, E.P.; Fang, W.; Tsang, H. Understanding residents’ environmental knowledge in a metropolitan city of Hong Kong, China. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 21, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J. Geo-Graphing: Writing the World in Geography Classrooms; Institution of Education in London: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brothers, C.C.; Fortner, R.W.; Mayer, V.J. The Impact of Television News on Public Environmental Knowledge. J. Environ. Educ. 1991, 22, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostman, R.E.; Parker, J.L. A Public’s Environmental Information Sources and Evaluations of Mass Media. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Media Use and Global Warming Perceptions. Commun. Res. 2009, 36, 698–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.J.; Riley, M. Traditional Ecological Knowledge from the internet? The case of hay meadows in Europe. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, E.; Roehrig, G. Constructing Media Artifacts in a Social Constructivist Environment to Enhance Students’ Environmental Awareness and Activism. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2014, 24, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Kong, Y.; Chang, H. Media Use and Health Behavior in H1N1 Flu Crisis: The Mediating Role of Perceived Knowledge and Fear. Atl. J. Commun. 2015, 23, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vaithianathan, S. A fresh look at understanding Green consumer behavior among young urban Indian consumers through the lens of Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, M.I.; Tanwir, N.S. Do pro-environmental factors lead to purchase intention of hybrid vehicles? The moderating effects of environmental knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.-S.; Ooi, H.-Y.; Goh, Y.-N. A moral extension of the theory of planned behavior to predict consumers’ purchase intention for energy-efficient household appliances in Malaysia. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, H. Merging Theory of Planned Behavior and Value Identity Personal norm model to explain pro-environmental behaviors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, E.M.; Goldberg, L.R.; Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. Profiling the “Pro-Environmental Individual”: A Personality Perspective. J. Pers. 2011, 80, 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jagers, S.C.; Martinsson, J.; Matti, S. The Environmental Psychology of the Ecological Citizen: Comparing Competing Models of Pro-Environmental Behavior. Soc. Sci. Q. 2016, 97, 1005–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Wei, W. Consumers’ Pro-Environmental Behavior and Its Determinants in the Lodging Segment. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.; Wilson, M.R. Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Gender differences in Egyptian consumers? green purchase behaviour: The effects of environmental knowledge, concern and attitude. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, G.; Chi, O.H.; Gursoy, D. An examination of the gap between carbon offsetting attitudes and behaviors: Role of knowledge, credibility and trust. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S. Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 31, 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–358. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.S.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Hashim, N.H.N.; Rashid, M.; Omar, N.A.; Ahsan, N.; Ismail, D. Small-scale households renewable energy usage intention: Theoretical development and empirical settings. Renew. Energy 2014, 68, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, W.; Farhat, K.; Arif, I. Regular to sustainable products: An account of environmentally concerned consumers in a developing economy. Int. J. Green Energy 2020, 18, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W.; Ford, N. The household energy gap: Examining the divide between habitual- and purchase-related conservation behaviours. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 1425–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, N.P. Information Systems Innovation for Environmental Sustainability. MIS Q. 2010, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, H.; Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Examining antecedents of consumers’ pro-environmental behaviours: TPB extended with materialism and innovativeness. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Saghaleini, A. What Drives Ranchers’ Intention to Conserve Rangelands: The Role of Environmental Concern (A Case Study of Angoshteh Watershed in Borujerd County, Iran). J. Rangel. Sci. 2021. Available online: http://www.rangeland.ir/article_681126.html (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutsaert, P.; Pieniak, Z.; Regan, A.; McConnon, A.; Kuttschreuter, M.M.M.M.; Lores, M.; Lozano-Monterrubio, N.; Guzzon, A.; Santare, D.; Verbeke, W. Social media as a useful tool in food risk and benefit communication? A strategic orientation approach. Food Policy 2014, 46, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. Does education increase pro-environmental behavior? Evidence from Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 116, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaiser, F.; Schultz, P.W.; Berenguer, J.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Tankha, G. Extending Planned Environmentalism. Eur. Psychol. 2008, 13, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.N.; Taylor, C.J.; Strick, S.K. Wine consumers’ environmental knowledge and attitudes: Influence on willingness to purchase. Int. J. Wine Res. 2009, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onel, N.; Mukherjee, A. Consumer knowledge in pro-environmental behavior. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 13, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | A | CR | AVE | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-environmental behavior | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.17 |

| Pro-environmental intention | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.40 |

| Attitude | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Subjective norms | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.57 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Environmental knowledge | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.72 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Media use | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.51 | - | - |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Pro-environmental behavior | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2-Pro-environmental intention | 0.57 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3-Attitude | 0.41 | 0.40 | - | - | - | - |

| 4-Subjective norms | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.49 | - | - | - |

| 5-Perceived behavioral control | 0.53 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 0.80 | - | - |

| 6-Environmental knowledge | 0.53 | 0.74 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.76 | - |

| 7-Media use | 0.60 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| Hypotheses | Β | t Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | |||

| Attitude → Intentions | 0.08 | 1.88 | H1: Not supported |

| Subjective norms → Intentions | 0.13 * | 2.19 | H2: Supported |

| PBC → Intentions | 0.25 ** | 3.25 | H3: Supported |

| PBC → PEB | 0.14 * | 2.07 | H4: Supported |

| Intentions → PEB | 0.23 ** | 3.64 | H5: Supported |

| Environmental knowledge → Intentions | 0.38 ** | 5.47 | H6: Supported |

| Environmental knowledge → PEB | 0.13 * | 1.96 | H7: Supported |

| Media use → Intentions | 0.08 | 1.89 | H8: Not supported |

| Media use → PEB | 0.40 ** | 8.03 | H9: Supported |

| Media use → Attitude | 0.10 | 1.56 | H10: Not supported |

| Media use → Subjective norms | 0.25 ** | 4.31 | H11: Supported |

| Media use → PBC | 0.21 ** | 3.81 | H12: Supported |

| Media use → Environmental knowledge | 0.26 ** | 4.77 | H13: Supported |

| Indirect effect | |||

| Media use → Attitude → Intentions | 0.01 | 1.05 | 0.00–0.03 |

| Media use → Subjective norms → Intentions | 0.03 | 1.77 | 0.00–0.07 |

| Media use → PBC → Intentions | 0.05 * | 2.52 | 0.02–0.10 |

| Media use → Environmental knowledge → Intentions | 0.10 ** | 3.86 | 0.05–0.15 |

| Media use → Environmental knowledge → PEB | 0.03 | 1.71 | 0.00–0.07 |

| Media use → Intentions → PEB | 0.02 | 1.57 | 0.00–0.05 |

| Media use → PBC → PEB | 0.03 | 1.86 | 0.00–0.07 |

| Subjective norms → Intentions → PEB | 0.03 | 1.80 | 0.00–0.07 |

| PBC → Intentions → PEB | 0.06 * | 2.29 | 0.02–11 |

| Environmental knowledge → Intentions → PEB | 0.09 ** | 2.72 | 0.04–0.16 |

| Total effect | |||

| Media use → Intentions | 0.28 ** | 4.70 | - |

| Media use → PEB | 0.53 ** | 11.14 | - |

| Attitude → PEB | 0.02 | 1.35 | - |

| Subjective norms → PEB | 0.03 | 1.80 | - |

| PBC → PEB | 0.19 ** | 2.98 | - |

| Environmental knowledge → PEB | 0.22 ** | 3.46 | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karimi, S.; Liobikienė, G.; Saadi, H.; Sepahvand, F. The Influence of Media Usage on Iranian Students’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158299

Karimi S, Liobikienė G, Saadi H, Sepahvand F. The Influence of Media Usage on Iranian Students’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability. 2021; 13(15):8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158299

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarimi, Saeid, Genovaitė Liobikienė, Heshmatollah Saadi, and Fatemeh Sepahvand. 2021. "The Influence of Media Usage on Iranian Students’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior" Sustainability 13, no. 15: 8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158299