Residents’ Perception of a Collaborative Approach with Artists in Culture-Led Urban Regeneration: A Case Study of the Changdong Art Village in Changwon City in Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Collaborative Approach

2.2. Culture-Led Urban Regeneration

2.3. Artist Participation in Culture-Led Urban Regeneration

2.4. Research Significance and Purpose

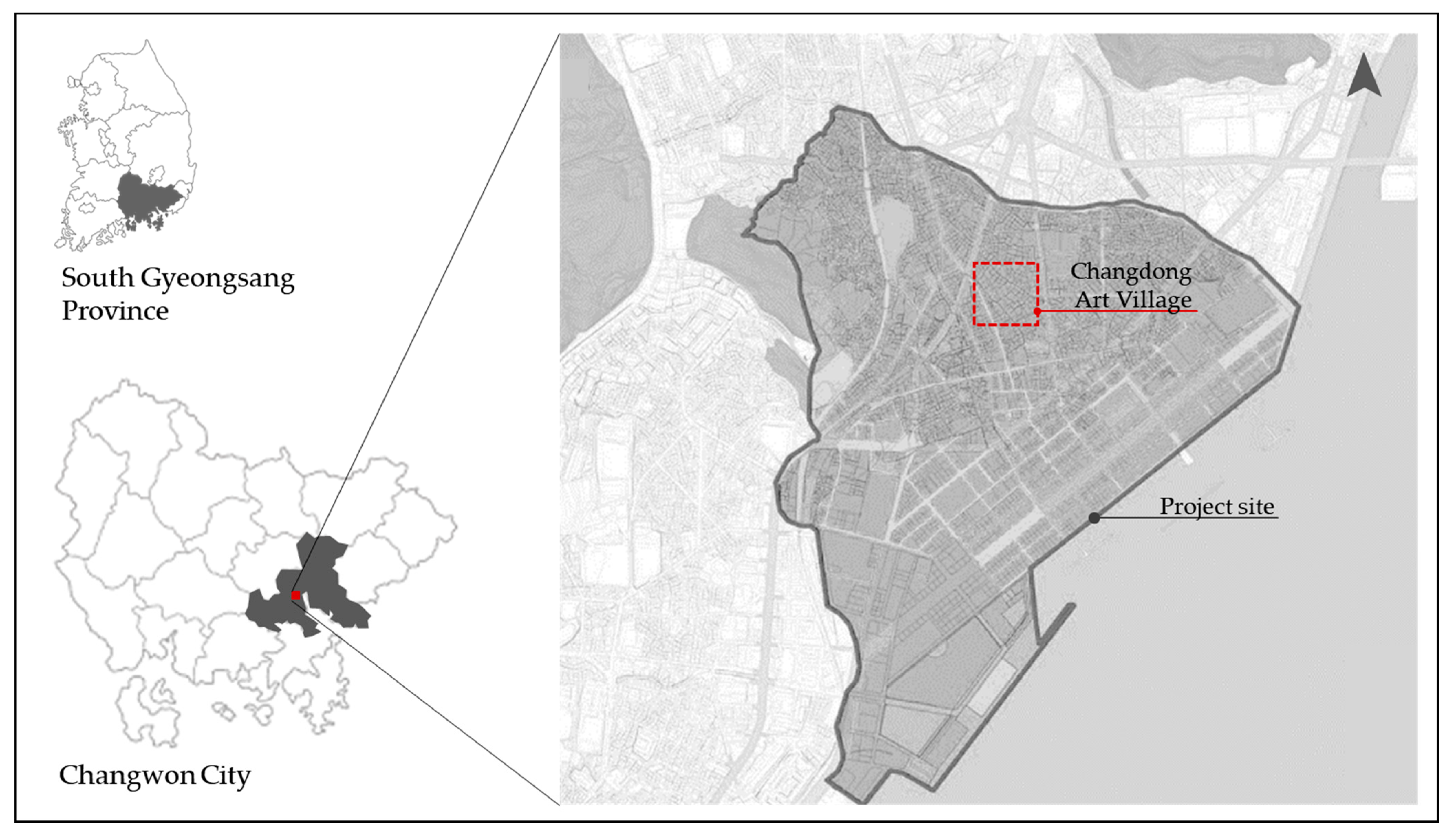

3. Culture-Led Urban Regeneration in Changwon City

3.1. Overview of the Urban Renewal Projects

3.2. Collaborative Network between Artists and Residents

4. Research Method

4.1. Analytical Framework

4.2. Selecting the Control Group

4.3. Measurement Instrument

4.4. Research Hypotheses

5. Empirical Results

Regression Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Respondents | Gender | Age Group | Ownership of Property | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | 10 s | 20 s | 30 s | 40 s | 50 s | 60 s~ | One’s Own | Jeonse * | Rent | ||||||

| (n) | 78 | 111 | 2 | 19 | 29 | 52 | 52 | 31 | 127 | 36 | 26 | |||||

| (%) | 41.3 | 58.7 | 1.1 | 10.3 | 15.7 | 28.1 | 28.1 | 16.8 | 67.2 | 19.0 | 13.8 | |||||

| Respondents | Residential Type | Family Member | Duration | |||||||||||||

| Detached House | Multi-Family Residential | Apartment | Studio Apartment | Flats Above Retail | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Average (Year) | |||||||

| (n) | 50 | 19 | 83 | 11 | 26 | 26 | 37 | 44 | 82 | 3.2 | ||||||

| (%) | 26.5 | 10.1 | 43.9 | 5.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 19.6 | 23.3 | 43.4 | |||||||

Appendix B

| Dependent Variable | Questionnaire | Factor Analysis | Credibility | ||

| Factor Loadings | SS Loadings | Proportion Var. | Cronbach’s α | ||

| Resident satisfaction and the expectation with urban renewal project | Satisfaction with urban renewal projects | 0.58 | 3.16 | 0.63 | 0.89 |

| Expectations for improving living environments | 0.85 | ||||

| Expectations for improving the local economy | 0.94 | ||||

| Expectations for improving neighborly relations | 0.75 | ||||

| Expectations for the result of the renewal project | 0.81 | ||||

Appendix C

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Resident satisfaction and expectation with urban renewal project | 1 | |||||||||

| (2) Level of satisfaction with living environments | 0.220 | *** | 1 | |||||||

| (3) Neighborly trust | 0.392 | *** | 0.088 | 1 | ||||||

| (4) Need for urban renewal projects | 0.407 | *** | 0.027 | 0.136 | * | 1 | ||||

| (5) Level of the resident’s opinions reflected in the project | 0.695 | *** | 0.182 | ** | 0.268 | *** | 0.196 | *** | 1 | |

| (6) Experience (or amount) of participation in urban renewal programs | 0.198 | *** | -0.279 | 0.183 | ** | 0.193 | *** | 0.011 | 1 | |

References

- Hall, T.; Robertson, I. Public Art and Urban Regeneration: Advocacy, claims and critical debates. Landsc. Res. 2001, 26, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. Down by the sea: Visual arts, artists and coastal regeneration. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2015, 24, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.L.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, Z.J. Contested memory amidst rapid urban transition: The cultural politics of urban regeneration in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2020, 102, 102755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodey, B. Art-ful places: Public art to sell public spaces? In Place Promotion: The Use of Publicity and Marketing to Sell Towns and Regions; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1994; pp. 153–179. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Law Information Center. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engMain.do (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Urban Regeneration Information System. Available online: https://www.city.go.kr/index.do (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Chung, H.; Kim, H. Revitalizing Urban Space and Cultivating Its Creativity by Culture and Arts: A Case Study of Seoul Art Spaces Geumcheon, Mullae, and Seogyo. Geogr. J. Korea 2011, 45, 279–293. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J. A Comparative Study on Creation Network of Mullae in Seoul, Daein Art Market in Gwangju, Totatoga in Busan. Seoul Stud. 2013, 14, 159–173. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H. Can we implant an artist community? A reflection on government-led cultural districts in Korea. Cities 2016, 56, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.M. The Effect of Creative Space Supporting Project on The Artist’s Continues The Intention to Move and Regional Revitalization: Focused on Totatoga in Busan. Master’s Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea, 2015. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Cha, D.I. A Study on the User’s Consciousness about City Brand of Urban Regeneration: Focused on the Chang-dong Art Village in Chang-won. J. Brand Des. Assoc. Korea 2015, 13, 17–28. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.Y.; Kim, Y.; Shin, J.W.; Kim, J.T. A Study on the Factor Analysis of Commercial Regeneration Strategy in Chang-won(Masan) City. J. Resid. Environ. Inst. Korea 2017, 15, 157–169. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Son, J.-M.; Koo, J.-H. An Analysis of the Effect of the Support Program for Gwangju Dae-in Art Market on the Sustainable Activity Intent of Artists. J. Korea Plan. Assoc. 2019, 54, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Choi, Y. A Study on Retailers’ Recognition about Commercial Power Altering Due to Urban Regeneration Project: Case of Changwon Urban Regeneration Priority Project. J. Korean Soc. Civ. Eng. 2018, 38, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.K.; Shon, J.H. The regenerated old city center in Masan as the culture-led center: Focused on the case of Changwon Urban Regeneration Priority Project. Urban Plan. 2018, 5, 26–30. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.H. An Analysis on Characteristics of the Process of Creative City Formation through Urban Regeneration: Focusing on Dashanzi 798 Art Zone in Beijing and Chang-dong Art Village in Changwon. J. Gov. Stud. 2013, 8, 55–94. Available online: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART001832448 (accessed on 3 June 2021). (In Korean).

- Seo, I.J. An Empirical Analysis on the Type of Cultural Urban Regeneration: Focused on the Case of Masan Old Downtown in Changwon City. Resid. Environ. 2016, 14, 363–382. Available online: http://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE07091971 (accessed on 3 June 2021). (In Korean).

- Brown, A.; O’Connor, J.; Cohen, S. Local music policies within a global music industry: Cultural quarters in Manchester and Sheffield. Geoforum 2000, 31, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haughton, G.; While, A. From corporate city to citizens city? Urban leadership after local entrepreneurialism in the United Kingdom. Urban Aff. Rev. 1999, 35, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, U.S. Urban regeneration governance, community organizing, and artists’ commitment: A case study of Seongbuk-dong in Seoul. City Cult. Soc. 2020, 21, 100328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobadilla, N.; Goransson, M.; Pichault, F. Urban entrepreneurship through art-based interventions: Unveiling a translation process. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 31, 378–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.; Sykes, H. Urban Regeneration: A Handbook; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T.H.; Lee, J.; Yap, M.H.; Ineson, E.M. The role of stakeholder collaboration in culture-led urban regeneration: A case study of the Gwangju project, Korea. Cities 2015, 44, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J.; Mccarthy, T.; Mccarthy, T. The Theory of Communicative Action; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Planning through debate: The communicative turn in planning theory. Town Plan. Rev. 1992, 63, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forester, J. Planning in the Face of Power; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E. Planning Theory’s Emerging Paradigm: Communicative Action and Interactive Practice. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1995, 14, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Retracking America: A Theory of Transactive Planning; Anchor Press: Norwell, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bäcklund, P.; Mäntysalo, R. Agonism and institutional ambiguity: Ideas on democracy and the role of participation in the development of planning theory and practice—the case of Finland. Plan. Theory 2010, 9, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. Collaborative planning in the network: Consensus seeking in urban planning issues on the Internet—the case of China. Plan. Theory 2013, 12, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forester, J. Critical Theory, Public Policy, and Planning Practice; SUNY Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sager, T. Communicative Planning Theory; Avebury: Aldershot, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E. Group Processes and the Social Construction of Growth Management: Florida, Vermont, and New Jersey. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1992, 58, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. The communicative turn in planning theory and its implications for spatial strategy formations. Environ. Plan B Plan. Des. 1996, 23, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, L.; Xu, Z. Collaborative governance: A potential approach to preventing violent demolition in China. Cities 2018, 79, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Enhancing Collaborative Innovation in the Public Sector. Adm. Soc. 2011, 43, 842–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlak, A.K.; Heikkila, T. Building a Theory of Learning in Collaboratives: Evidence from the Everglades Restoration Program. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2011, 21, 619–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kort, M.; Klijn, E.-H. Public-Private Partnerships in Urban Regeneration Projects: Organizational Form or Managerial Capacity? Public Adm. Rev. 2011, 71, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keating, M.; De Frantz, M. Culture-led strategies for urban regeneration: A comparative perspective on Bilbao. Int. J. Iber. Stud. 2004, 16, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators; Earthscan: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, C.; Greene, L.; Matarasso, F.; Bianchini, F. The Art of Regeneration. In Urban Renewal through Cultural Activity; Stroud: Comedia: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nedučin, D.; Krklješ, M.; Gajić, Z. Post-socialist context of culture-led urban regeneration—Case study of a street in Novi Sad, Serbia. Cities 2019, 85, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Measure for Measure: Evaluating the Evidence of Culture’s Contribution to Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 959–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferilli, G.; Sacco, P.L.; Blessi, G.T.; Forbici, S. Power to the people: When culture works as a social catalyst in urban regeneration processes (and when it does not). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 25, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darchen, S.; Tremblay, D.-G. The local governance of culture-led regeneration projects: A comparison between Montreal and Toronto. Urban Res. Pr. 2013, 6, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, C.; Freestone, P. The impact of culture-led regeneration on regional identity in north east England. Reg. Urban Regen. Eur. Peripher. 2008, 51, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, E.C.M.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Ou, Y. Urban community regeneration and community vitality revitalization through par-ticipatory planning in China. Cities 2021, 110, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzini, D.; Rossi, U. Becoming a Creative City: The Entrepreneurial Mayor, Network Politics and the Promise of an Urban Renaissance. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 1037–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G. It’s not just a question of taste: Gentrification, the neighbourhood, and cultural capital. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Markusen, A. Urban Development and the Politics of a Creative Class: Evidence from a Study of Artists. Environ. Plan. A: Econ. Space 2006, 38, 1921–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.Y. Cultural entrepreneurs and urban regeneration in Itaewon, Seoul. Cities 2016, 56, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S. “Our Tyne”: Iconic Regeneration and the Revitalisation of Identity in NewcastleGateshead. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulldemolins, J.R. Culture and authenticity in urban regeneration processes: Place branding in central Barcelona. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 3026–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Paddison, R. Introduction: The Rise and Rise of Culture-led Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Place-making for the people: Socially engaged art in rural China. China Inf. 2018, 32, 244–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A. Urban Regeneration: From the Arts Feel Good’ Factor to the Cultural Economy: A Case Study of Hoxton, London. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1041–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, B. Urban Regeneration, Arts Programming And Major Events. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2004, 10, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Miles, S.; Stark, P. Culture-Led Urban Regeneration and The Revitalisation of Identities in Newcastle, Gateshead and the North East of England. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2004, 10, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, M.; Nasar, J.L.; Chun, B. Neighborhood satisfaction, physical and perceived naturalness and openness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basolo, V.; Strong, D. Understanding the neighborhood: From residents’ perceptions and needs to action. Hous. Policy Debate 2002, 13, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.; Converse, P.E.; Rodgers, W.L. The Quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations, and Satisfactions; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1976; Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=h_QWAwAAQBAJ (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Mohan, J.; Twigg, L. Sense of Place, Quality of Life and Local Socioeconomic Context: Evidence from the Survey of English Housing, 2002/03. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 2029–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, K.J.; Shelton, G.G. Assessment of neighborhood satisfaction by residents of three housing types. Soc. Indic. Res. 1987, 19, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D.M.; Baba, Y. Social determinants of neighborhood attachment. Sociol. Spectr. 1990, 10, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassopoulos, A.; Monnat, S.M. Do Perceptions of Social Cohesion, Social Support, and Social Control Mediate the Effects of Local Community Participation on Neighborhood Satisfaction? Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S. The Effect of Urban Regeneration on the Village Satisfaction and Community Spirit of the Citizens of Seoul. Korean Assoc. Public Soc. 2014, 4, 66–92. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Suh, N.J.; Kim, H.C. A Study on the Determinants of Residents’ Satisfaction in Urban Regeneration Projects: Focused on Urban Vitality Promotion Projects. Korea Real Estate Soc. 2019, 53, 25–46. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Chang-dong Art Village. Available online: http://changdongartvillage.kr (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Changwon City Urban Regeneration Center. Available online: http://www.cwurc.or.kr (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Joo, H.S.; Ma, S.R.; Jo, J.H. Strategies of Urban Regeneration Considering the Contexts of South Gyeongsang Province; Gyeongnam Institute: Sacheon, Korea, 2019; pp. 1–450. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- The Revitalization Plan of Changwon Urban Regeneration Project; Ministry of Environment and Urban Affairs Bureau: Changwon, Korea, 2014. (In Korean)

- Kim, T.D.; Sung, S.A.; Hwang, H.Y. Comparative resident satisfaction studies between Changwon and Cheongju regener-ation projects. J. Environ. Policy Adm. 2014, 22, 153–181. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.G.; Hwang, H.Y. Effects of Collaborative Governance on the Residents Satisfaction Level in Self-Help Residential Regeneration Projects: Focused on Cheong-Ju Sajik 2-Dong. Korean Reg. Dev. Assoc. 2014, 26, 207–228. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.H.; Song, H.S. A Study on Factors Affecting Satisfaction with Urban Regeneration Project between Participants: Focused on the Resident Group and Expert Group in Urban Regeneration Areas in Seoul. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2017, 33, 3137. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias, C.; Palen, J. Neighborhood satisfaction, expectations, and urban revitalization. J. Urban Aff. 1986, 8, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, J. Migration as an Adjustment to Environmental Stress. J. Soc. Issues 1966, 22, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speare, A. Residential Satisfaction as an Intervening Variable in Residential Mobility. Demography 1974, 11, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.A.; Moore, E.G. The intra-urban migration process: A perspective. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 1970, 52, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permentier, M.; Bolt, G.; Van Ham, M. Determinants of neighbourhood satisfaction and perception of neighbourhood reputa-tion. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 977–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Woolley, M.; Mowbray, C.; Reischl, T.M.; Gilster, M.; Karb, R.; Macfarlane, P.; Gant, L.; Alaimo, K. Predictors of Neighborhood Satisfaction. J. Community Pract. 2006, 14, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Content |

|---|---|

| Type | Support/renewal of neighborhoods |

| Site | Seongho, Dongseo, and Odong neighborhoods of Masan-happo district, Changwon city, South Gyeongsang province |

| Area | 1,780,000 m2 |

| Period | 2014–2017 (4 years) |

| Budget | 20 billion KRW (national expenditure = 10 billion KRW, local expenditure = 10 billion KRW) |

| Category | Content |

|---|---|

| Site | Changdong Art Village |

| Period | 2015–2017 (3 years) |

| Content | (1) Strengthening artists’ abilities and network (2) Communicating with residents and business owners (3) Organizing diverse cultural programs (4) Managing operational systems for the Art Village |

| Organizer | Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) The local government of Changwon city |

| Budget | 1 billion KRW (national expenditure = 500 million KRW, provincial expenditure = 150 million KRW, city expenditure = 350 million KRW) * |

| Category | Content |

|---|---|

| Art School | Cultural and art classes for citizen Providing 10–12 courses in every the first/second half of the year The number of people in a course is 10–15 people (e.g.,) the classes in the first half of 2021: barista, harmonica, calligraphy, metalcraft, photography, Western painting, Argentine tango, etc. |

| Art Ground | Artists leading daily classes for citizens or visitors who can make a diverse stuff (e.g.,) the classes in 2021: wood cutting board, card wallet, light fixture, accessories, flowerpot, etc. |

| Cultural Event | Concert of celebrating the Village opening (May), culture art festival for children (May), The Art Village’s Culture and Art Festival (October/November), flea market |

| Others | The Art Village Tour Program Collaboration with the local culture center ((e.g.,) the artists had art classes(calligraphy, painting, modern art, etc.) in the Culture Hall in the local department store) |

| Sacheon | Gimhae | Miryang | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Support/renewal of city centers | Support/renewal of neighborhoods | |

| Location | Dongseo, Seongu, and Dongseogeum neighborhoods, Sacheon city, South Gyeongsang province | Mugye neighborhood, Gimhae city, South Gyeongsang province | Naei and Naeil neighborhoods, Miryang city, South Gyeongsang province |

| Area | 291,829 m2 | 199,600 m2 | 147,000 m2 |

| Period | 2018–2022 (5 years) | 2018–2022 (5 years) | 2018–2021 (4 years) |

| Budget | 25 billion KRW (national expenditure 15 = billion KRW, local expenditure = 10 billion KRW) | 25 billion KRW (national expenditure = 15 billion KRW, local expenditure = 10 billion KRW) | 16.7 billion KRW (national expenditure = 10 billion KRW, local expenditure = 6.7 billion KRW) |

| Variable | Questionnaire Item | Scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Resident satisfaction and expectation with the urban regeneration project | Please indicate your opinion on the level of satisfaction with the urban renewal project in your neighborhood. | ① Extremely unsatisfied ~ ④ Extremely satisfied | |

| Please indicate your expectations(in living environment, economic, neighborly relation, urban regeneration project) for the ongoing urban renewal project in your neighborhood. | ① Extremely unexpected ~ ④ Extremely expected | |||

| Independent variables | Resident participation in the urban regeneration project | Experience(or amount) of participation in urban renewal programs | How many times have you participated in urban renewal programs (including public hearing/discussion, residents’ council, education, seminar) on the ongoing project in your neighborhood? | ① No, ② Yes (① No = 0, ② Yes = 1) |

| Level of the resident’s opinions reflected in the project | Please indicate your general opinion on the degree of the residents’ opinion reflected on the ongoing urban renewal project in your neighborhood. | ① Extremely low ~ ④ Extremely high | ||

| Need for urban renewal projects | Please indicate your general opinion on the need to implement an urban renewal project in your neighborhood. | ① Extremely unnecessary ~④ Extremely necessary | ||

| Neighborly relation | Neighborly trust | What is your subjective trust level with neighborly relations in your neighborhood? | ① Extremely unreliable ~ ④ Extremely reliable | |

| Living condition | Level of satisfaction with living environments | How satisfied are you with the overall living environment of your current neighborhood as compared with surrounding neighborhoods? | ① Extremely unsatisfied ~ ④ Extremely satisfied | |

| Variables | Comparison between Groups * | Hypothesis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resident participation in urban regeneration project | Experience (or amount) of participation in urban renewal programs | Experimental group > Control group | Hypothesis 1 |

| Level of the resident’s opinions reflected in the project | Hypothesis 2 | ||

| Need for urban renewal projects | Hypothesis 3 | ||

| Neighborly relation | Neighborly trust | Hypothesis 4 | |

| Variables | Average | Standard Deviation | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expectations for improving living environments | 3.1 | 0.7 | 1 | 4 |

| Expectations for improving the local economy | 3 | 0.7 | 1 | 4 |

| Expectations for improving neighborly relations | 3 | 0.7 | 1 | 4 |

| Expectations for the result of the renewal project | 3 | 0.7 | 1 | 4 |

| Satisfaction with urban renewal projects | 2.7 | 0.8 | 1 | 4 |

| Level of satisfaction with living environments | 3.7 | 1.2 | 1 | 4 |

| Need for urban renewal projects | 3.5 | 0.6 | 2 | 4 |

| Level of the resident’s opinions reflected in the project | 2.8 | 0.8 | 1 | 4 |

| Neighborly trust | 2.8 | 0.7 | 1 | 4 |

| Experience (or amount) of participation in urban renewal programs | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1 | 4 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | B | β | ||||

| SE | t(p) | SE | t(p) | ||||

| Resident participation in the urban renewal project | Need for urban renewal projects | 0.235 | 0.192 | 0.274 | 0.283 | ||

| 0.089 | 2.654 | ** | 0.067 | 4.092 | *** | ||

| Level of the resident’s opinions reflected in the project | 0.461 | 0.573 | 0.458 | 0.549 | |||

| 0.064 | 7.190 | *** | 0.056 | 8.170 | *** | ||

| Experience (or amount) of participation in urban renewal programs | 3.722 | 0.220 | 0.760 | 0.065 | |||

| 1.187 | 3.135 | *** | 0.834 | 0.912 | |||

| Neighborly relation | Neighborly trust | 0.162 | 0.204 | 0.120 | 0.134 | ||

| 0.060 | 2.695 | ** | 0.063 | 1.913 | * | ||

| Living condition | Level of satisfaction with living environments | 0.346 | 0.385 | 0.032 | 0.047 | ||

| 0.071 | 4.900 | *** | 0.046 | 0.693 | |||

| Intercept | −19.87 | 0 | 7.182 | 0.000 | |||

| 9.197 | −2.161 | ** | 6.069 | 1.183 | |||

| R (Adj-R2) | 0.846 (0.822) | 0.581 (0.561) | |||||

| F-statistic (p) | 35.21 *** | 29.40 *** | |||||

| Significant Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Comparison between Groups | Hypothesis Testing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β(p) | β(p) | ||||||

| Resident participation in urban regeneration project | Experience (or amount) of participation in urban renewal programs | 0.220 | *** | 0.065 | - | Hypothesis 1 (supported) | |

| Level of the resident’s opinions reflected in the project | 0.573 | *** | 0.549 | *** | Experimental group > Control group | Hypothesis 2 (supported) | |

| Need for urban renewal projects | 0.192 | ** | 0.283 | *** | Experimental group < Control group | Hypothesis 3 (unsupported) | |

| Neighborly relation | Neighborly trust | 0.204 | ** | 0.134 | * | Experimental group > Control group | Hypothesis 4 (supported) |

| Living condition | Level of satisfaction with living environments | 0.385 | *** | 0.047 | - | - | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, Y.; Jung, C.; Joo, H. Residents’ Perception of a Collaborative Approach with Artists in Culture-Led Urban Regeneration: A Case Study of the Changdong Art Village in Changwon City in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158320

Baek Y, Jung C, Joo H. Residents’ Perception of a Collaborative Approach with Artists in Culture-Led Urban Regeneration: A Case Study of the Changdong Art Village in Changwon City in Korea. Sustainability. 2021; 13(15):8320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158320

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Yoonjee, Changmu Jung, and Heesun Joo. 2021. "Residents’ Perception of a Collaborative Approach with Artists in Culture-Led Urban Regeneration: A Case Study of the Changdong Art Village in Changwon City in Korea" Sustainability 13, no. 15: 8320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158320