Entrepreneurship in Crisis: The Determinants of Syrian Refugees’ Entrepreneurial Intentions in Turkey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Attitude towards the Behaviour (ATB)

2.2. Subjective Norms (SN)

2.3. Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC)

2.4. Refugee Context (RC)

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Context

3.2. Sampling Method

3.3. Description of Sample Characteristics

3.4. Variables Measurement

4. Research Results

4.1. Exploratory Study

4.2. Confirmatory Study

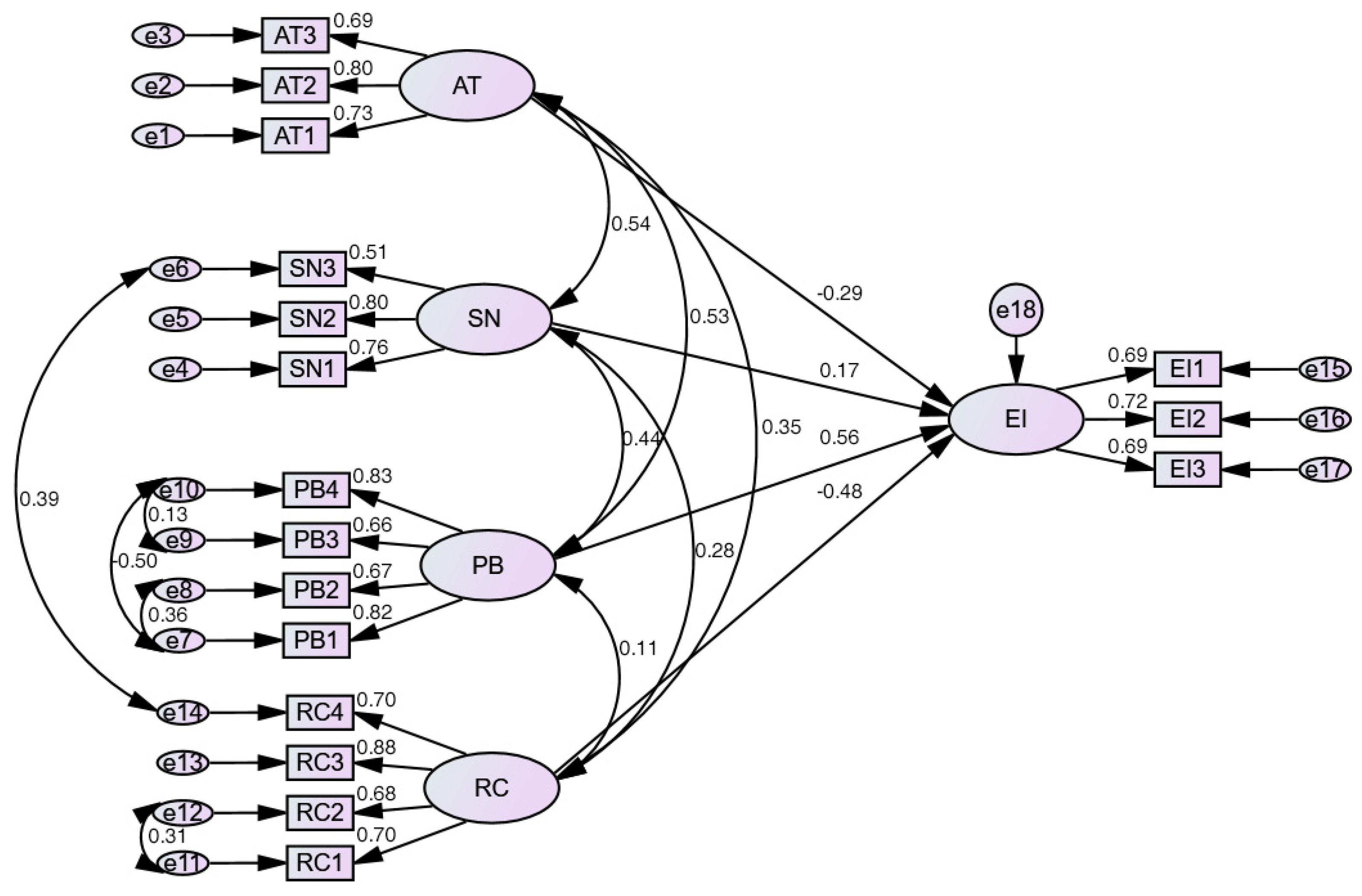

4.3. Testing the Structural Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Statements | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards the Behaviour | ||||||

| 1 | High income is a sign that I will be successful in life. | |||||

| 2 | Most business owner-managers are well off. | |||||

| 3 | I feel that money is the only thing I can really count on in asylum life. | |||||

| Subjective Norms | ||||||

| 4 | My family support me to start my own business. | |||||

| 5 | Friends support me to start my own business. | |||||

| 6 | If I become an entrepreneur, it enhances my social position among my family and close friends. | |||||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | ||||||

| 7 | I can control the creation process of a new firm. | |||||

| 8 | If I tried to start a firm, I would have a high probability of succeeding. | |||||

| 9 | I trust in my skills and abilities to start a business. | |||||

| 10 | I refuse to give up if I don’t succeed in setting up a business. | |||||

| Refugee Context | ||||||

| 11 | Funding programs announced by humanitarian organizations helped me start my own business. | |||||

| 12 | Knowledge and advisory support provided by international organizations is very necessary to overcome difficulties in setting up a business. | |||||

| 13 | Turkish laws include big facilities for refugees in particular to start their businesses. | |||||

| 14 | In Turkey, my own project it can bring me advantages such as obtaining a work permit and Turkish citizenship. | |||||

| Entrepreneurial intention | ||||||

| 15 | I saved money to start a business. | |||||

| 16 | I always look for information on how to set up a firm. | |||||

| 17 | I spent a lot of time learning how to start a firm. | |||||

References

- Obschonka, M.; Hahn, E.; Bajwa, N. Personal agency in newly arrived refugees: The role of personality, entrepreneurial cognitions and intentions, and career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 105, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.M.; Benzing, C.; McGee, C. Ghanaian and Kenyan entrepreneurs: A comparative analysis of their motivations, success characteristics and problems. J. Dev. Entrep. 2007, 12, 295–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijdenberg, L.; Masurel, E. Entrepreneurial motivation in a least developed country: Push factors and pull factors among MSES in Uganda. J. Enterprising Cult. 2013, 21, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abada, T.; Hou, F.; Lu, Y. Choice or necessity: Do immigrants and their children choose self-employment for the same reasons? Work Employ. Soc. 2014, 28, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, F.; Sepulveda, L.; Syrett, S. Enterprising refugees: Contributions and challenges in deprived urban areas. Local Econ. 2007, 22, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Locke, E.A. The relationship of achievement motivation to entrepreneurial behavior: A meta-analysis. Hum. Perform 2004, 17, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, W.H.; Calo, T.J.; Weer, C.H. Affiliation motivation and interest in entrepreneurial careers. J. Manag. Psychol 2012, 27, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J. How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob 2006, 1, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudé, W. Entrepreneurship and Economic Development. In International Development: Ideas, Experience, and Prospects; Currie-Alder, B., Kanbur, R., Malone, D.M., Medhora, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wennekers, S.; Thurik, R. Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Bus. Econ. 1999, 13, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouse, S.; Durrah, O.; McElwee, G. Rural women entrepreneurs in Oman: Problems and opportunities. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouse, S.; McElwee, G.; Meaton, J.; Durrah, O. Barriers to rural women entrepreneurs in Oman. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 998–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Gharib, M.; Durrah, O.; Mishra, V. Social well-being and livelihood challenges in conflict economies: A study of Syrian citizens’ perception of geopolitical fragility. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2020, 6, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGMM. Temporary Protection; Directorate General of Migration Management: Ankara, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan in Response to the Syria Crisis, (3RP); Turkey Country Chapter; UNHCR: Ankara, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, E.D. The career adaptive refugee: Exploring the structural and personal barriers to refugee resettlement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 105, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, B.; Lambrecht, J. Barriers to refugee entrepreneurship in Belgium: Towards an explanatory model. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2008, 34, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthanar, S.; MacEachen, E.; Premji, S.; Bigelo, B. Entrepreneurial experiences of Syrian refugee women in Canada: A feminist grounded qualitative study. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 57, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Nabi, G.; Krueger, N.F. British and Spanish entrepreneurial intentions: A comparative study. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2013, 33, 73–107. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Entrialgo, M.; Iglesias, V. The moderating role of entrepreneurship education on the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 1209–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chliova, M.; Farny, S.; Salmivaara, V. Supporting Refugees in Entrepreneurship; OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chavali, K.; Mavuri, S.; Durrah, O. Factors affecting social entrepreneurial intent: Significance of student engagement initiatives in higher education institutions. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, L.; Yli–Renko, H. The impact of environment and entrepreneurial perceptions on venture-creation efforts: Bridging the discovery and creation views of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, C.; Koenig, M. Determinants of Entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B. Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intentions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 442–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.A.; Gartner, W.B. Properties of emerging organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüthje, C.; Franke, N. The ‘making’ of an entrepreneur: Testing a model of entrepreneurial intent among engineering students at MIT. R D Manag. 2003, 33, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mishra, C.S.; Zachary, R.K. The Theory of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Res. J. 2015, 5, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H. Career Development of Refugees. In International Handbook of Career Guidance; Athanasou, J., Perera, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P. Culture, structure and regional levels of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1995, 7, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Brazeal, D.V. Entrepreneurial Potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Prac. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship. In Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship; Kent, C.A., Sexton, D.L., Vesper, K.H., Eds.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Van Gelderen, M.; Tornikoski, E.T. Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schlaegel, C.S.; He, X.; Engle, R. The direct and indirect influences of national culture on entrepreneurial intentions: A fourteen nation study. Int. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 597–609. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, B. Entrepreneurial intentions research: A review and outlook. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2015, 13, 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper, R.; Léger-Jarniou, C. Entrepreneurship intention among French Grande ÉCole and university students: An application of Shapero’s model. Ind. High. Educ. 2006, 20, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Questions raised by a reasoned action approach: Comment on Ogden (2003). Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douglas, E.; Shepherd, D. Self-employment as a career choice: Attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, and utility maximization. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 26, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.A.; Brewster, S.E.; Thomson, J.A.; Malcolm, C.; Rasmussen, S. Testing the bi-dimensional effects of attitudes on behavioural intentions and subsequent behaviour. Br. J. Psychol. 2015, 106, 656–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, I.; Gulzar, M.A. Understanding the Eco-Friendly Role of Drone Food Delivery Services. Deep Theory Plan. Behav. Sustain. 2020, 12, 1440. [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. Entrepreneurial motivation and self-employment: Evidence from expectancy theory. Int. Entrep. Mana. J. 2017, 13, 1097–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fitzsimmons, J.R.; Douglas, E.J. Entrepreneurial attitudes and entrepreneurial intentions, a cross-cultural study of potential entrepreneurs in India, China, Thailand and Australia. In Proceedings of the Babson-Kauffman Entrepreneurial Research Conference, Wellesley, MA, USA, 9–11 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kor, Y.Y.; Mahoney, J.T.; Michael, S.C. Resources, capabilities, and entrepreneurial perceptions. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 1187–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denanyoh, R.; Adjei, K.; Nyemekye, G.E. Factors that impact on entrepreneurial intention of tertiary students in Ghana. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. 2015, 5, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, B.A.; Shah, N. Developing attitudes and intentions among potential entrepreneurs. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D.; Selcuk, S.S. Which factors affect entrepreneurial intention of university students? J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2009, 33, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Keeley, R.; Klofsten, M.; Parker, G.; Hay, M. Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterp. Innov. Manag. Stud. 2001, 2, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M.; Shinnar, R.; Toney, B.; Llopis, F.; Fox, J. Explaining entrepreneurial intention of university students: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2009, 15, 571–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, N.E.; Kennedy, J. Enterprise education: Influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- La Barbera, F.; Ajzen, I. Control interactions in the theory of planned behavior: Rethinking the role of subjective norm. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gist, M.E.; Mitchell, T.R. Self-efficacy: A Theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1992, 77, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitkin, S.B.; Weingart, L.R. Determinants of risky decision-making behavior: A test of the mediating role of risk perceptions and propensity. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1573–1592. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V.; Duggal, S. How the consumer’s attitude and behavioural intentions are influenced: A case of online food delivery applications in India? Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 15, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgcomb, E.L.; Klein, J.A. Opening Opportunities, Building Ownership: Fulfilling the Promise of Microenterprise in the United States; The Aspen Institute: Washington, WA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gharib, M.; Allil, K.; Durrah, O.; Satouf, M. Impact of sustainable development on financial performance. Int. J. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2018, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Khalid, N.; Ahmed, U. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention among foreigners in Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.D.; Bygrave, W.D.; Autio, E.; Cox, L.W.; Hay, H. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor; 2002 Executive Report; Babson College, London Business School and Kauffman Foundation: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter, C.; Bruton, G.D.; Chen, J. Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). UNHCR Resettlement Handbook; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Isidor, R.; Dau, L.A.; Kabst, R. The more the merrier? Immigrant share and entrepreneurial activities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 42, 698–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naude, W.; Siegel, S.; Marchand, K. Migration, entrepreneurship and development: Critical questions. IZA J. Migr. 2017, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alrawadieh, Z.; Karayilan, E.; Cetin, G. Understanding the challenges of refugee entrepreneurship in tourism and hospitality. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 717–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, M.; Woller, G. Microenterprise development programs in the United States and in the developing world. World Dev. 2003, 31, 1567–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Z.; Silove, D.; Phan, T.; Bauman, A. Long-term effect of psychological trauma on the mental health of Vietnamese refugees resettled in Australia: A population-based Study. Lancet 2002, 360, 1056–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, M.; Bygrave, W. A dynamic model of entrepreneurial learning. Entrep. Theory Prac. 2001, 25, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.A. The economically rich refugees: A case study of the business operations of Istanbul-based Syrian refugee businesspeople. Int. Migr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.; Alkassim, R. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Given, L.M. Convenience Sample. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E.R. Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.; Gefen, D. Validation guidelines for is positivist research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 380–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohammad, D.; Durrah, O.; Ahmed, F. Deciphering the motives, barriers and integration of Syrian refugee entrepreneurs into Turkish society: A SEM Approach. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2021, 23, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ghouse, S.; McElwee, G.; Durrah, O. Entrepreneurial success of cottage-based women entrepreneurs in Oman. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dwivedi, Y.; Choudrie, J.; Brinkman, W. Development of a survey instrument to examine consumer adoption of broadband. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2006, 106, 700–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambulkar, S.; Blackhurst, J.; Grawe, S. Firm’s resilience to supply chain disruptions: Scale development and empirical examination. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 33, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrah, O.; Allil, K.; Gharib, M.; Hannawi, S. Organizational pride as an antecedent of employee creativity in the petrochemical industry. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bish, A.; Newton, C.; Johnston, K. Leader vision and diffusion of HR policy during change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2015, 28, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives, Structural Equation Modeling. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Durrah, O.; Chaudhary, M. Negative behaviors among employees: The impact on the intention to leave work. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 17, 106–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, T.; Cheung, C.; Shi, N.; Lee, M. Gender differences in satisfaction with Facebook users. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 182–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structure equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrah, O.; Allil, K.; Alkhalaf, T. The intellectual capital and the learning organization: A case study of Saint Joseph Hospital, Paris. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2018, 14, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrah, O. Injustice perception and work alienation: Exploring the mediating role of employee’s cynicism in healthcare sector. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. Software review: Software programs for structural equation modeling: AMOS, EQS, and LISREL. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1999, 16, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Maresch, D.; Harms, R.; Kailer, N.; Wimmer-Wurm, W. The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruiz-Alba, J.; Vallespín, M.; Martín-Sánchez, V.; Rodriguez-Molina, M. The moderating role of gender on entrepreneurial intentions: A TPB perspective. Intang. Cap. 2015, 11, 92–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gelderen, M.; Brand, M.; Van Praag, M.; Poutsma, E.; Bodewes, W.; Van Gils, A. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions by means of the theory of planned behavior. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 538–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L.; Isaksen, E. New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 866–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Soomro, B.A. Investigating entrepreneurial intention among public sector university students of Pakistan. Educ. Train. 2017, 59, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizri, R.M. Refugee-entrepreneurship: A social capital perspective. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinnar, R.S.; Nayır, D. Immigrant Entrepreneurship in an Emerging Economy: The case of Turkey. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Items | Loading | Communalities | Eigen Value | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes (AT) | AT1 | 0.672 | 0.672 | 2.186 | 12.856 |

| AT2 | 0.772 | 0.714 | |||

| AT3 | 0.834 | 0.728 | |||

| Subjective Norms (SN) | SN1 | 0.832 | 0.758 | 1.981 | 11.654 |

| SN2 | 0.763 | 0.710 | |||

| SN3 | 0.619 | 0.662 | |||

| Perceived Behavior (PB) | PB1 | 0.722 | 0.689 | 2.839 | 16.698 |

| PB2 | 0.865 | 0.774 | |||

| PB3 | 0.769 | 0.660 | |||

| PB4 | 0.744 | 0.687 | |||

| Refugee Context (RC) | RC1 | 0.793 | 0.730 | 2.828 | 16.634 |

| RC2 | 0.840 | 0.734 | |||

| RC3 | 0.808 | 0.752 | |||

| RC4 | 0.753 | 0.701 | |||

| Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI) | EI1 | 0.751 | 0.645 | 2.190 | 12.883 |

| EI2 | 0.775 | 0.700 | |||

| EI3 | 0.774 | 0.708 | |||

| KMO = 0.776 | Bartlett’s Test = 930.787 Sig. = 0.000 | σ2 = 70.725 | |||

| Variable | Item | Cronbach’s Alpha | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes (AT) | AT1 | 0.779 | 4.3661 | 0.70601 | −1.245 | 1.372 |

| AT2 | ||||||

| AT3 | ||||||

| Subjective Norms (SN) | SN1 | 0.705 | 4.0437 | 0.59836 | −0.897 | 2.086 |

| SN2 | ||||||

| SN3 | ||||||

| Perceived Behavior (PB) | PB1 | 0.838 | 4.2787 | 0.61674 | −0.608 | 0.023 |

| PB2 | ||||||

| PB3 | ||||||

| PB4 | ||||||

| Refugee Context (RC) | RC1 | 0.847 | 3.6393 | 0.97545 | −0.388 | −0.607 |

| RC2 | ||||||

| RC3 | ||||||

| RC4 | ||||||

| Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI) | EI1 | 0.730 | 3.3169 | 0.81633 | 0.020 | −0.337 |

| EI2 | ||||||

| EI3 |

| Components | Total | Variance | Cumulative | Total | Variance | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.736 | 27.861 | 27.861 | 4.736 | 27.861 | 27.861 |

| 2 | 3.267 | 19.218 | 47.078 | |||

| . | . | . | . | |||

| . | . | . | . | |||

| 16 | 0.205 | 1.208 | 98.931 | |||

| 17 | 0.182 | 1.069 | 100.000 |

| Constructs | Items | Standardized Factor Loadings SFL > 0.50 | Square Multiple Correlation SMC > 0.30 | Composite Reliability CR > 0.70 | Average Variance Explained AVE > 0.50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes (AT) | AT1 | 0.729 | 0.532 | 0.805 | 0.581 |

| AT2 | 0.798 | 0.637 | |||

| AT3 | 0.686 | 0.470 | |||

| Subjective Norms (SN) | SN1 | 0.760 | 0.577 | 0.785 | 0.552 |

| SN2 | 0.799 | 0.638 | |||

| SN3 | 0.513 | 0.363 | |||

| Perceived Behavior (PB) | PB1 | 0.819 | 0.671 | 0.894 | 0.565 |

| PB2 | 0.666 | 0.444 | |||

| PB3 | 0.658 | 0.432 | |||

| PB4 | 0.830 | 0.689 | |||

| Refugee Context (RC) | RC1 | 0.698 | 0.487 | 0.909 | 0.596 |

| RC2 | 0.685 | 0.469 | |||

| RC3 | 0.884 | 0.782 | |||

| RC4 | 0.702 | 0.493 | |||

| Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI) | EI1 | 0.693 | 0.480 | 0.810 | 0.541 |

| EI2 | 0.718 | 0.515 | |||

| EI3 | 0.694 | 0.482 |

| Variable | T > 0.05 | VIF < 10 | AT | SN | PB | CR | EI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 0.731 | 1.368 | 1 | 0.403 ** | 0.420 ** | 0.288 ** | −0.034 | 0.762 |

| SN | 0.741 | 1.350 | 1 | 0.390 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.075 | 0.742 | |

| PB | 0.765 | 1.307 | 1 | 0.162 | 0.292 ** | 0.751 | ||

| CR | 0.871 | 1.149 | 1 | −0.329 ** | 0.772 | |||

| EI | - | - | 1 | 0.735 |

| Fit Indices | CMIN/DF | RMR | RMSEA | GFI | CFI | IFI | PGFI | PNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | 1.775 | 0.072 | 0.079 | 0.905 | 0.907 | 0.911 | 0.582 | 0.623 |

| Recommended | <5 | <0.08 | <0.08 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.50 | >0.50 |

| Hypotheses | Path | Estimate | T-Value; T > 1.96 | p-Value; p < 0.05 | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | AT  EI EI | −0.29 | −1.84 | 0.065 | Not Supported |

| H2 | SN  EI EI | 0.17 | 1.27 | 0.203 | Not Supported |

| H3 | PB  EI EI | 0.56 | 3.56 | *** | Supported |

| H4 | RC  EI EI | −0.48 | −3.78 | *** | Supported |

Significant Effect,

Significant Effect,  Insignificant Effect. *** Significant at 0.001.

Insignificant Effect. *** Significant at 0.001.Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almohammad, D.; Durrah, O.; Alkhalaf, T.; Rashid, M. Entrepreneurship in Crisis: The Determinants of Syrian Refugees’ Entrepreneurial Intentions in Turkey. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8602. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158602

Almohammad D, Durrah O, Alkhalaf T, Rashid M. Entrepreneurship in Crisis: The Determinants of Syrian Refugees’ Entrepreneurial Intentions in Turkey. Sustainability. 2021; 13(15):8602. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158602

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmohammad, Dawoud, Omar Durrah, Taher Alkhalaf, and Mohamad Rashid. 2021. "Entrepreneurship in Crisis: The Determinants of Syrian Refugees’ Entrepreneurial Intentions in Turkey" Sustainability 13, no. 15: 8602. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158602

APA StyleAlmohammad, D., Durrah, O., Alkhalaf, T., & Rashid, M. (2021). Entrepreneurship in Crisis: The Determinants of Syrian Refugees’ Entrepreneurial Intentions in Turkey. Sustainability, 13(15), 8602. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158602