Entrepreneurship Competence in Pre-Service Teachers Training Degrees at Spanish Jesuit Universities: A Content Analysis Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Spanish Context: Pre-Service or Initial Teacher Education in Higher Education

3. Reference Frameworks on Entrepreneurial Competence: EntreComp, EntreCompEdu, ECI Order

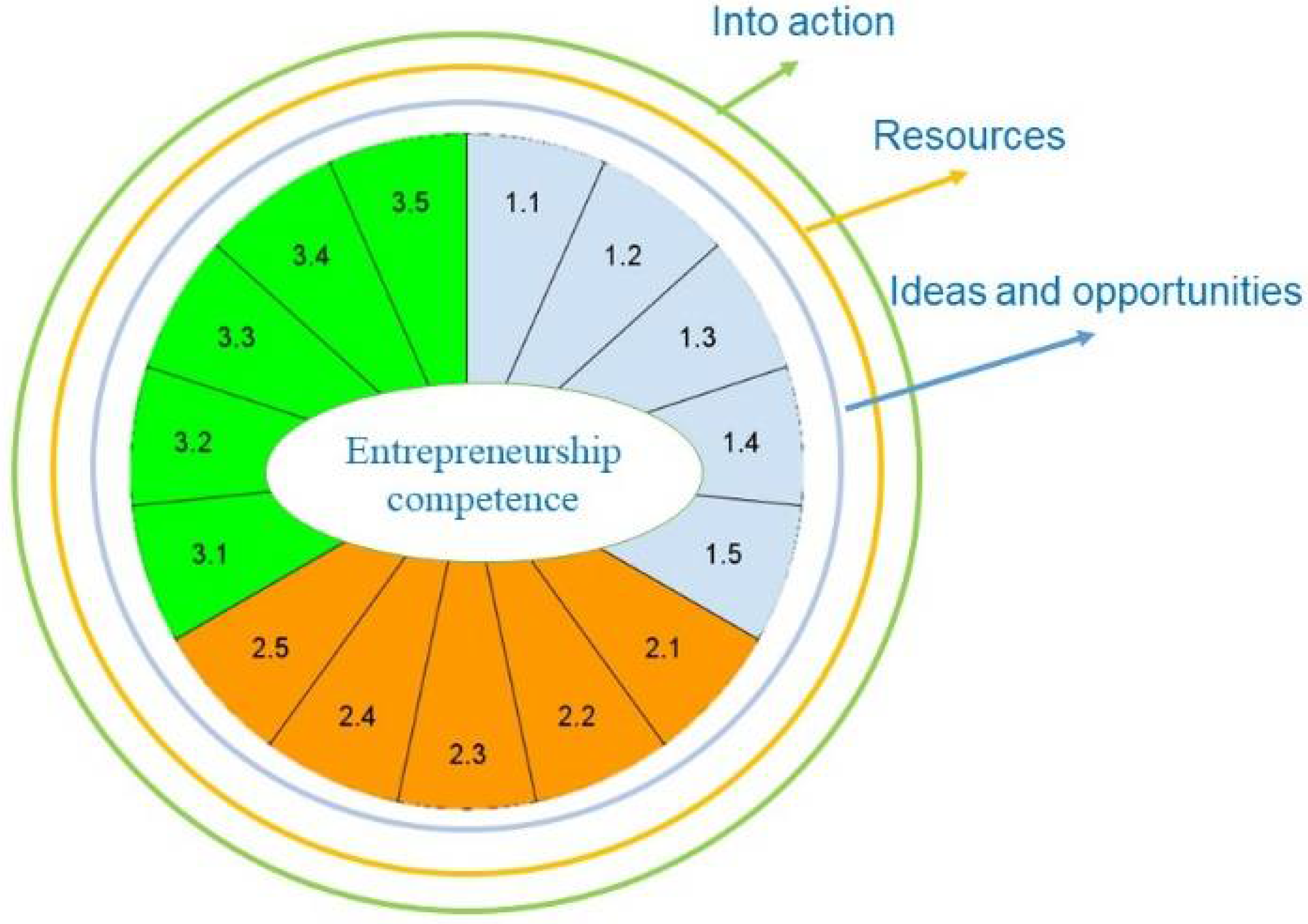

3.1. EntreComp

3.2. EntreCompEdu

3.3. ECI Order

4. Aims of the Study

- 1.

- To compare the competence areas proposed by the European Commission’s EC Framework for the citizen (EntreComp) and the EC Framework for the educator (EntreCompEdu) proposed by Bantani Education within the framework of the European Union’s Erasmus + program.

- 2.

- Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu, to analyze the incorporation of EC in the formulation of the competencies of the primary education degrees offered by the Spanish Jesuit universities.For this second objective, four more specific objectives are set out:

- 1.1

- Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu, to recognize the incorporation of EC in the basic competencies proposed by the Spanish Jesuit universities that offer primary education degrees.

- 2.1

- Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu, to recognize the incorporation of EC in the general competencies proposed by the Spanish Jesuit universities that offer primary education degrees.

- 3.1

- Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu, to recognize the incorporation of EC in the transversal competencies proposed by the Spanish Jesuit universities that offer primary education degrees.

- 4.1

- Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu, to recognize the incorporation of EC in the specific competencies proposed by Spanish Jesuit universities that offer primary education degrees.

5. Method

6. Results

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Commission of the European Communities. Green Paper Entrepreneurship in Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bacigalupo, M.; Kampylis, P.; Punie, Y.; Van den Brande, G. EntreComp: The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bughin, J.; Hazan, E.; Lund, S.; Dahlstrom, P.; Wiesinger, A.; Subramaniam, A. Skill Shift. Automation and the Future of the Workforce; McKinsey Global: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. La Iniciativa Emprendedora en la Enseñanza Superior, Especialmente en Estudios no Empresariales; Comisión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. Entrepreneurship Education: Enabling Teachers as a Critical Success Factor; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. Plan de Acción sobre Emprendimiento 2020: Relanzar el Espíritu Emprendedor en Europa; Comisión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. Educación en Emprendimiento. Guía del Educador, Unidad «Emprendimiento 2020»; Comisión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. Entrepreneurship Education: A Road to Success; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. Agenda de Capacidades Europea para la Competitividad Sostenible, la Equidad Social y la Resiliencia; Comisión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle, A.; Kariv, D.; Matlay, H. (Eds.) The Role and Impact of Entrepreneurship Education: Contextual Perspectives; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Grigg, R. EntreCompEdu, a professional development framework for entrepreneurial education. Educ. Train. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.; Lewis, K. A review of entrepreneurship education research. Educ. Train. 2018, 60, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackeus, M. Entrepreneurship in Education. What, Why, When, How; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boldureanu, G.; Ionescu, A.M.; Bercu, A.M. Entrepreneurship Education through Successful Entrepreneurial Models in Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hameed, I.; Irfan, Z. Entrepreneurship education: A review of challenges, characteristics and opportunities. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 2, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, A.S. Teachers’ perception on the significance of entrepreneurship educational as a tool for youth empowerment. Int. J. Sci. Res. Multidiscip. Stud. 2019, 5, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sadewo, Y.D. The Effect of Learning Outcomes in Entrepreneurship Education Programs of Interest in Entrepreneurship. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Economics Education and Entrepreneurship, Batam, Indonesia, 28–31 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, C.; van der Sijde, P. Understanding the concept of the entrepreneurial university from the perspective of higher education models. High. Educ. 2014, 68, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, H.; Paiva, T. Entrepreneurship Education: Background and Future. In Handbook of Research on Approaches to Alternative Entrepreneurship Opportunities; Leitão, J.G., Cagica, L., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Von Graevenitz, G.; Harhoff, D.; Weber, R. The effects of entrepreneurship education. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2010, 76, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Welsh, D.H.B.; Tullar, W.L.; Nemati, H. Entrepreneurship education: Process, method, or both? J. Innov. Knowl. 2016, 1, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning; Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Entrepreneurship Education at School in Europe; Eurydice Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Deveci, I.; Seikkula-Leino, J. A review of entrepreneurship education in teacher education. Malays. J. Learn. Instr. 2018, 15, 105–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Europea. Una Nueva Agenda de Capacidades para Europa. Trabajar Juntos para Reforzar el Capital Humano, la Empleabilidad y la Competitividad; Comisión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, T.; Alves, M.L.; Sampaio, J.H. Entrepreneurship Education: Background and Future. In Global Considerations in Entrepreneurship Education and Training; Cagica, L., Dias, A., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Wibowo, A.; Saptono, A.; Suparno, S. Does Teachers’ Creativity Impact on Vocational Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention? J. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Suska, M. Entrepreneurial studies in higher education: Some insights for Entrepreneurship education in Europe. Horyz. Polityki 2018, 9, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Atmojo, I.R.W.; Sajidan, S.; Sunarno, W.; Ashadi, A. Improving the Entrepreneurship Competence of Pre-Service Elementary Teachers on Professional Education Program through the Skills of Disruptive Innovators. Elem. Educ. Online 2019, 18, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Galvão, A.; Ferreira, J.J.; Marques, C. Entrepreneurship education and training as facilitators of regional development: A systematic literature review. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2018, 25, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zangeneh, H.; Kavousi, A.; Bahrami, Z. Teachers’ Attitudes toward Teaching-Learning Methods of Entrepreneurship Education in Elementary Education. Educ. Strateg. Med Sci. 2020, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. La educación Para el Emprendimiento en el Sistema Educativo Español. 2015. RediE. Available online: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/d/20842/19/0 (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Arruti, A.; Paños-Castro, J. Análisis de las menciones del grado de educación primaria desde la perspectiva de la competencia emprendedora. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2019, 30, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orden ECI/3857/2007, de 27 de Diciembre, Por la Que se Establecen Los Requisitos Para la Verificación de los Títulos Universitarios Oficiales Que Habiliten Para el Ejercicio de la Profesión de Maestro en Educación Primaria. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 29 de diciembre de 2007. Volume 312, pp. 53747–53750. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2007/12/29/pdfs/A53747-53750.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de Diciembre, por la que se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 30 de Diciembre de 2010. Volume 314, pp. 122868–122953. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2020/12/30/pdfs/BOE-A-2020-17264.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de Diciembre, Para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 10 de Diciembre de 2013. Volume 295, pp. 1–64. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2013/BOE-A-2013-12886-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Penaluna, A.; Penaluna, K.; Polenakovikj, R. Developing entrepreneurial education in national school curricula: Lessons from North Macedonia and Wales. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 3, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guibert, J.M. Para Comprender la Pedagogía Ignaciana; Ediciones Mensajero: Bilbao, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lowney, C. El Liderazgo al Estilo de los Jesuitas; Granica: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass Warner, K.; Lieberman, A.; Roussos, P. Ignatian Pedagogy for Social Entrepreneurship: Twelve Years Helping 500 Social and Environmental Entrepreneurs Validates the GSBI Methodology. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2016, 11, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooke, P.; Zhiyuan, W.; Domfang, M.C.; Okoh, M.; Bossou, C. The Power of Purpose: Jesuits for Social Entrepreneurship; Santa Clara University, Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. EntreComp: The European Entrepreneurship Competence Framework; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, E.; Weicht, R.; McMullan, L.; Price, A. EntreComp into Action—Get Inspired, Make It Happen: A User Guide to the European Entrepreneurship Competence Framework; Office for Official Publications of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Real Decreto 1509/2008, de 12 de Septiembre, Por el Que se Regula el Registro de Universidades, Centros y Títulos. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 25 de Septiembre de 2008. Volume 232, pp. 38854–38857. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2008/09/12/1509/dof/spa/pdf (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Ruiz Olabuénaga, J.I. Teoría y Práctica de la Investigación Cualitativa; Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Mexico City, México, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, R. Metodología de la Investigación Educativa; Editorial La Muralla: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Arruti, A.; Paños-Castro, J. How do future primary education student teachers assess their entrepreneurship competences? An analysis of their self-perceptions. J. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, A.; Poblete, M. Competency-Based Learning: A Proposal for the Evaluation of Generic Competencies, 2nd ed.; University of Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arruti, A.; Paños-Castro, J. International entrepreneurship education for pre-service teachers: A longitudinal study. Educ. Train. 2020, 62, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Llanos, L.M.; Hernández, T.; Mejía, D.; Heilbron, J.; Martín, J.; Mendoza, J.; Senior, D. Competencias emprendedoras en básica primaria: Hacia una educación para el emprendimiento. Pensam. Gestión 2017, 43, 150–188. [Google Scholar]

- Paños-Castro, J. Educación emprendedora y metodologías activas para su fomento. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2017, 20, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Autonomous Community | University | Decree | Entrepreneurial Competence to Be Developed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basque Country | Deusto University | Decree 236/2015, of December 22, establishing the Basic Education curriculum and implementing it in the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country. | Article 7. Basic transversal competencies. (d) Competence for initiative and entrepreneurship. To show initiative by managing the entrepreneurial process with a resolution, efficiency, and respect for ethical principles in different contexts and personal, social, academic, and work situations, in order to transform ideas into actions. |

| Andalusia | Jaén University and Sagrada Familia Professional Centre. Loyola Andalucía University. | Decree 97/2015, of March 3, which establishes the organization and curriculum of Primary Education in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia. | Article 6. Key competences. (f) Sense of initiative and entrepreneurial spirit. |

| Madrid | Pontificia Comillas University. | Decree 89/2014, of July 24, of the Governing Council, by which the Primary Education Curriculum is established for the Community of Madrid. | Article 5. Competences. 6. Sense of initiative and entrepreneurial spirit. * The students will be able to take some other area in the block of subjects of free autonomic configuration, as is the case of “Creativity and Entrepreneurship”. The competence called “sense of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial spirit”, associated with this area will be included in the “Creativity and Entrepreneurship” block of subjects. Entrepreneurship and creativity, understood as the ability to build and transform the circumstances and the environment in which we live, refer to a constant exercise of “creating value” whatever the context: personal, social, or business. |

| Catalonia | Ramón Llull University. | Decree 119/2015, of June 23, on the organization of the teaching of Primary Education. | Article 6 and Annex 1. Basic competencies. 8. Competence of autonomy, personal initiative, and entrepreneurship. It is the acquisition of awareness and application of a set of interrelated personal values and attitudes, such as responsibility, perseverance, self-knowledge and self-esteem, creativity, self-criticism, emotional control, the ability to choose, to imagine projects and to turn ideas into actions, to learn from mistakes, to take risks and to work in teams. |

| Competences Areas | Competences |

|---|---|

| 1. Professional knowledge and understanding of entrepreneurial education | 1.1 Knowing entrepreneurial education |

| 1.2 Valuing entrepreneurial education | |

| 1.3 Understanding how learners develop entrepreneurial competences | |

| 2. Planning | 2.1 Setting entrepreneurial learning goals that are ethical and sustainable |

| 2.2 Making connections | |

| 2.3 Creating an empowering entrepreneurial learning environment | |

| 3. Teaching and training | 3.1 Instructing to enthuse and engage |

| 3.2 Creating value for others | |

| 3.3 Teaching through real-world contexts | |

| 3.4 Encouraging self-awareness and self-confidence to support learning | |

| 3.5 Promoting productive working with others | |

| 4. Assessment | 4.1 Checking and reporting on progress |

| 4.2 Sharing feedback | |

| 4.3 Recognising progress and achievement | |

| 5. Professional Learning | 5.1 Evaluating impact |

| 5.2 Researching practice | |

| 5.3 Building and sustaining networks |

| 1. Know the curricular areas of primary education, the interdisciplinary relationship between them, the evaluation criteria, and the body of didactic knowledge about the respective teaching and learning procedures. |

| 2. Design, plan and evaluate teaching and learning processes, both individually and in collaboration with other teachers and professionals of the center. |

| 3. Effectively deal with language learning situations in multicultural and multilingual contexts. Encourage reading and critical commentary of texts from the various scientific and cultural domains contained in the school curriculum. |

| 4. Design and regulate learning spaces in contexts of diversity and that attend to gender equality, equity, and respect for human rights that shape the values of citizenship formation. |

| 5. Promote coexistence in the classroom and outside it, solve discipline problems, and contribute to the peaceful resolution of conflicts. To stimulate and value effort, perseverance, and personal discipline in students. |

| 6. Know the organization of primary schools and the diversity of actions that comprise its operation. Perform the functions of tutoring and guidance with students and their families, attending to the unique educational needs of students. To assume that the exercise of the teaching function must be perfected and adapted to scientific, pedagogical, and social changes throughout life. |

| 7. Collaborate with the different sectors of the educational community and the social environment. To assume the educational dimension of the teaching function and to promote democratic education for active citizenship. |

| 8. Maintain a critical and autonomous relationship with respect to knowledge, values, and public and private social institutions. |

| 9. Value the individual and collective responsibility in the achievement of a sustainable future. |

| 10. Reflect on classroom practices in order to innovate and improve teaching. Acquire habits and skills for autonomous and cooperative learning and promote it among students. |

| 11. Know and apply information and communication technologies in the classroom. To selectively discern audiovisual information that contributes to learning, civic formation, and cultural richness. |

| 12. Understand the role, possibilities, and limits of education in today’s society and the fundamental competencies that affect primary schools and their professionals. To know models of quality improvement with application to educational centers. |

| EntreComp | EntreCompEdu | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Competences areas | Competences | Competences | Competences areas |

| Ideas and opportunities | 1.1. Spotting opportunities | 2.2 Making connections | 2. Planning |

| 1.2 Creativity | 3.2 Creating value for others | 3. Teaching and training | |

| 1.3. Vision | 2.1 Setting entrepreneurial learning goals that are ethical and sustainable | 2. Planning | |

| 1.4 Valuing ideas | 4.3 Recognising progress and achievement | 4. Assessment | |

| 1.5 Ethical and sustainable thinking | 2.1 Setting entrepreneurial learning goals that are ethical and sustainable | 2. Planning | |

| Resources | 2.1 Self-awareness and self-efficacy | 3.4 Encouraging self-awareness and self-confidence to support learning 4.2 Sharing feedback 4.3 Recognising progress and achievement | 3. Teaching and training 4. Assessment |

| 2.2 Motivation and perseverance | 3.1 Instructing to enthuse and engage | 3. Teaching and training | |

| 2.3 Mobilising resources | 2.3 Creating an empowering entrepreneurial learning environment | 2. Planning | |

| 2.4 Financial and economic literacy | 3.3 Teaching through real-world contexts | 3. Teaching and training | |

| 2.5. Mobilising others | |||

| Into action | 3.1 Taking the initiative | 2.3 Creating an empowering entrepreneurial learning environment | 2. Planning |

| 3.2. Planning and management | 2.1 Setting entrepreneurial learning goals that are ethical and sustainable | 2. Planning | |

| 3.3 Coping with uncertainty, ambiguity and risk | 2.3 Creating an empowering entrepreneurial learning environment 3.4 Encouraging self-awareness and self-confidence to support learning | 2. Planning 3. Teaching and training | |

| 3.4 Working with others | 3.5 Promoting productive working with others 5.3 Building and sustaining networks | 3. Teaching and training 5. Professional learning | |

| 3.5 Learning through experience | 4.1 Checking and reporting on progress 4.2 Sharing feedback 5.1 Evaluating impact 5.2 Researching practice | 4. Assessment 5. Professional learning | |

| UD | UJ | LAU | PCU | RLLU | Total Sum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | 2/5 (40%) | 2/5 (40%) | 2/5 (40%) | 2/5 (40%) | 2/5 (40%) | 10 |

| GC | 15/44 (34%) | 12/50 (24%) | 8/12 (66,6%) | 5/16 (31,2%) | 18/20 (60%) | 58 |

| TC | 0 (0%) | 5/5 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 |

| SC | 39/75 (52%) | 13/69 (18, 8%) | 16/71 (22, 5%) | 20/85 (23, 5%) | 29/42 (20, 4%) | 117 |

| 56(29, 3%) | 32(16, 7%) | 27(14, 1%) | 27(14, 3%) | 49(25, 6%) | 191 (30%) |

| BC | GC | TC | SC | TOTAL | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | C | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | T | 2 | 3 | T | C | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | T | |||||

| EntreComp (222) | 1 | E1.1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 57 | |||||||||||||

| E1.2 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 9 | |||||||||||

| E1.3 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 26 | ||||||||||

| E1.4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | |||||||||||||||

| E1.5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 16 | |||||||||

| 2 | E2.1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 72 | ||||||||||||

| E2.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| E2.3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 23 | ||||||||

| E2.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| E2.5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 14 | 5 | 31 | 46 | ||||||||

| 3 | E3.1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 93 | |||||||||||

| E3.2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 26 | 33 | ||||||||||

| E3.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| E3.4 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 25 | 44 | ||||||||

| E3.5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 9 | ||||||||||||

| EntreCompEdu (138) | 1 | EDU1.1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 20 | ||||||||||||

| EDU1.2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 | |||||||||||||||

| EDU1.3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | EDU2.1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 14 | 48 | ||||||||

| EDU2.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| EDU2.3 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 19 | 30 | ||||||||

| 3 | EDU3.1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 34 | ||||||||||||||

| EDU3.2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| EDU3.3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| EDU3.4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |||||||||||||

| EDU3.5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 21 | |||||||||||

| 4 | EDU4.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| EDU4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| EDU4.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 5 | EDU5.1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 36 | ||||||||||||

| EDU5.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| EDU5.3 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 21 | ||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arruti, A.; Morales, C.; Benitez, E. Entrepreneurship Competence in Pre-Service Teachers Training Degrees at Spanish Jesuit Universities: A Content Analysis Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168740

Arruti A, Morales C, Benitez E. Entrepreneurship Competence in Pre-Service Teachers Training Degrees at Spanish Jesuit Universities: A Content Analysis Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168740

Chicago/Turabian StyleArruti, Arantza, Cristina Morales, and Estibaliz Benitez. 2021. "Entrepreneurship Competence in Pre-Service Teachers Training Degrees at Spanish Jesuit Universities: A Content Analysis Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168740

APA StyleArruti, A., Morales, C., & Benitez, E. (2021). Entrepreneurship Competence in Pre-Service Teachers Training Degrees at Spanish Jesuit Universities: A Content Analysis Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu. Sustainability, 13(16), 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168740