According to Abbasi et al. (2019) in Hunza Valley, communities have a “gender-egalitarian relationship,” which allows women to have social capital, own businesses, jobs, and take part in commercial activities. Social capital is also the reason for the women to pursue high education, and therefore, they are not highly dependent on men and are less vulnerable in disaster situations than the women of rest of Pakistan. During the data collection process, it was found that women and men do not have a gender egalitarian relationship. In the literature, two distinct concepts conceptualize gender egalitarianism: (gender) equality in the public sphere or gender roles in the private sphere, particularly within homes. Gender egalitarianism also involves the relative positioning of men and women in public domains such as politics, education, and labor market [

24]. Particularly in the context of disaster, there were several underlying factors related to women vulnerability which tacitly existed in the socio-cultural setting of Hunza Valley. Mulilis (1998) suggested that there is a difference in the engagement of males and females with hazard preparedness and mitigation activities, which could be due to the way they cognitively appraise the natural hazards and threats [

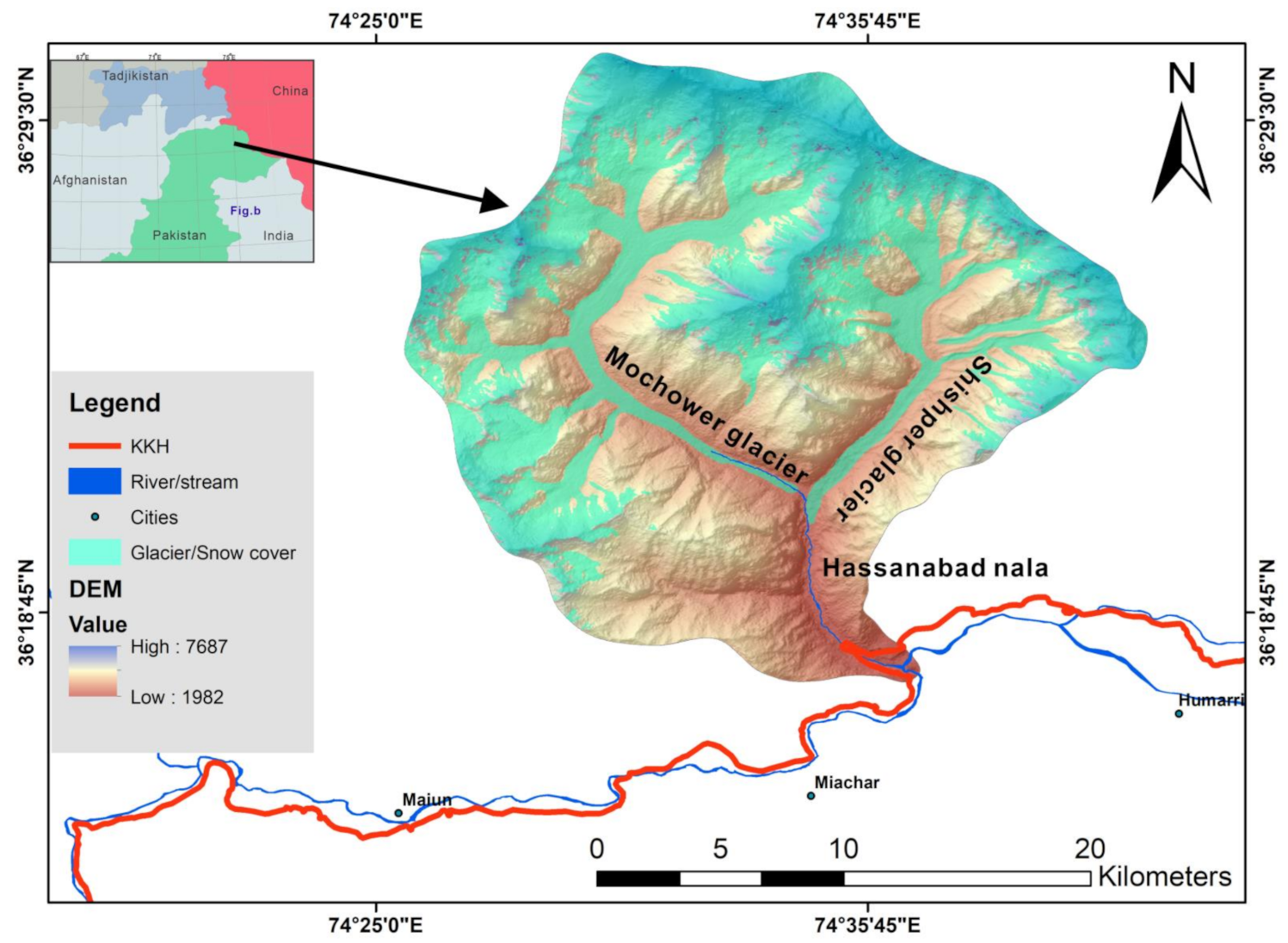

25]. Here the thematic analysis of the Shishper flood event is conducted through the gendered lens to dissect the experiences of men and women. In addition, the analysis will also show how disasters impact the lives of men and women differently according to their social and economic positionality at the communal and household level.

3.1. Gendered Perception of Hazard Risk and Vulnerability

Perception is usually influenced by factors such as age, gender, income and education, past damages and experiences with hazards, and access to information [

26,

27,

28]. Risk perception is used by the scientific community to measure public judgments, reactions, and acceptance of an event that drives human behaviors, decisions, and actions [

29]. The qualitative results of the study showed that in Hassanabad, both men and women deemed disaster and the existing vulnerability as natural and believed that when a disaster strikes, everyone is equally affected. God saves or kills whomever He wants. In a society where religion is deeply seated, people’s perceptions are usually intertwined. The interviewees demonstrated a rather complex and layered understanding of the environmental hazards. During the interview, the respondents did not separate their scientific knowledge, local knowledge and their religious beliefs. Their belief that God controls everything shaped up the general perception of people in terms of disaster and vulnerability. Interestingly, they also formed a correlation between climate change and extreme events which indicated their scientific understanding of natural hazards. However, for them there was still an element of ‘naturalness’ to the disasters. For the people the disasters were an “act of God,” and they occurred upon God’s will. Here it is important to note that language also influences the perceptions of local people. For example, the translation of “disaster” in Urdu is “

qudarti (natural),

aafat (disaster),” and “vulnerability” is “

ghair mehfooz (unsafe).” If the disaster is conceived as a natural phenomenon, then the whole causal chain and resultant impacts are trivialized by different stakeholders, mainly decision-makers [

30].

The discussion regarding men’s and women’s roles before and during natural hazard events, their strengths and weaknesses, the role of formal governmental institutions in disaster situations, and societal transformation in the recent decades helped the respondents to reflect deeper and focus more on their social positioning particularly from gender point of view. Three broad categories of perceptions emerged in the society as a result (i) men’s perception of the vulnerability of women (ii) older women’s perception of vulnerability of women (iii) young girls’ perception of women’s vulnerability.

Here, old indicates women above 40, and young indicates women between 17–25 years. These two women age groups represent a generational gap which is reflected in their perceptions. The women between the age of 25–40 had a blend of traditional and modern perception. The key differences between these categories are education and exposure. According to a report by ILO, the subordinate status of women in a society is the root cause of their vulnerability during disasters. The subordination is reflected in women’s economic insecurity, sexual and domestic violence, care-giving responsibilities, and kinship relations, among others [

31].

In Hassanabad, the vulnerability of women was associated with their physical attributes both by men and old women. According to both, the biological differentiation in the body functionality such as menstruation and pregnancy makes them more vulnerable. They argued that childbirth creates a deficiency of different vital components in women’s bodies, making them physically weak. Women who are caretakers of their family and family-owned land and cattle also do not have access to resources and experience to utilize the resources, making them more vulnerable during the hazard events. The financial dependence creates a lack of confidence and dims the ability to make decisions during stressful conditions. It was very interesting that the women in Hassanabad were not strictly restricted to their homes. They were active members of the community and maintained social relations. However, despite this involvement, women felt that they are emotional, mentally, and physically not prepared for the highly distressful time of disaster. A statement by an old woman, a mother of six children, shows not only the level of physical vulnerability but also their perception of themselves as women.

“Women are sick, they have high blood pressure and old age. Who can run at this age or be so vigilant? Women are sick, weak, and not agile.”

In the above statement, sickness, weakness, and agility could be analyzed as three separate issues in terms of physical sickness, emotional weakness, and lack of formal training. Although the emergency training sessions organized and conducted by AKAH are gender exclusive; women especially those who were old and stay at home mothers and caregivers did not feel confident that they were ready to face a hazard situation. The women however, agreed that if they were trained better and briefed properly about the situation, they could become emotionally strong during disaster situations. A married woman in her late twenties and mother of two children said,

“Women are emotional, and they are weak in decision making. During a disaster, like floods, some women cry over their land, their house, and other belongings in the house. They get emotional at that time. I think this is not right. Women must control their emotions, and they should help their male family members during this time. I do not know why women are overly attached to their houses and belongings. Everyone has a different perception.”

The deep-rooted sense of helplessness among women in disaster-like situations developed a high level of dependency on men. The gender inequality in a society is often expressed through the lower status and power of women as compared to men. These power dynamics are addressed by feminist theories such as women in development (WID), women and development (WED), and gender and development (GAD). The dependency of Hassanabad women can be analyzed through the conceptual lens of ‘power within’ and ‘power with’ which refers to one’s self-esteem and confidence and collective and organized power of a group with a unified goal [

32].

The men in Hassanabad, on the other hand, accepted this dependency as a part of their social responsibility being males. One man narrated that during the flood; they were aware of every community member’s health condition and were ready to take this responsibility of rescue and evacuation during the flood. The concept of ‘power to’ in this situation is extremely obvious because the men are quite easily stretching the limits of their boundaries to take on new roles and responsibilities without any resistance from women as an equal contender in this situation [

33]. A man in his late 20s said:

“There was a sick lady in one of the houses. She could not move, so she said everyone else to go. We stayed in touch with her while keeping an eye on the water. We planned her evacuation among ourselves in case the water level crosses the threshold.”

Within this context, we came across another woman, aged 32, who said

“I think women cannot do anything unless men are not there for them. They cannot make any decision on their own; they are not as brain smart as men.”

The above statement is an interesting reflection of women’s perception of their vulnerability. Rowlands (1997) termed it as ‘spiritual strength’ which enables an individual to recognize the way their lives are operated by power and to harness that power to alter their conditions [

34]. The low level of self-confidence in women shows that their vulnerability not only exists in the socio-economic and political context but is also present intangibly as part of their psychology and attitudes. During the data collection process, an interesting contradiction was found in the women of Hassanabad regarding their perceptions and actions. While they shared the stories of their inability to handle stress situation; their actions were simultaneously depicting another side. For example, a woman who is also a household head, decided to stay in their own house at the night of flood even though their house was very much vulnerable to flood due to physical proximity to the river. She said that she made a judgment call and stayed with the rest of the neighborhood even though she had rented a house in a safe location beforehand. Other instances are also highlighted later in the paper.

In this case, the contradiction could be attributed to of poor self-perception of women. The powerlessness expressed by women should be released through women empowerment interventions. The goal is to mobilize the resources such that the change comes from within and not from outside [

34]. The results might progress the society into achieving a ‘non-zero-sum power’ state [

33] where the power gained by women would not nullify the power held by men. Although the state of power equilibrium in a living society is idealistic, administrative regulation can at least ensure a near-equilibrium power state. In Hassanabad, AKAH has played a very active and positive role in women’s empowerment through developing and enhancing their power within.

Women also stated that excessive responsibility for their homes, children, and property makes them physically and emotionally weak. They claimed that in the case of less burden, maybe they will be less vulnerable and would respond better during disaster situations. During the interviews with the male respondents, they were asked about the role of women during disasters. Their immediate response was, “women cry and weep during the disasters.” The physical and emotional fragility of women served as a central debate for the majority of the respondents. They felt that in a crisis situation, women easily lose their nerves and most likely break down rather than becoming a proactive and responsible first responder. One man, aged 35, said:

“I think women are physically weak because of their responsibilities and bearing children. This is how the nature works. So, if in a situation where you can run and save your life, a woman might not be able to run well or in time or fast enough as compared to a man. If we look at this angle, then women are a little more vulnerable.”

The young girls aged 17–25 in Hassanabad were mostly school and college students. There was a visible difference in their attitude, conduct, and confidence. The young women respondents had an altogether different perception about themselves and their role in disaster situations. They claim that their education has changed their perception of hazards and their role during such difficult times. During the Shishper glacier event, the young women were actively involved in the community-based flood water monitoring via community volunteer programs. The volunteers, both boys and girls, were on duty throughout the night. They monitored the flood water level and communicated the latest development to the households where women, children, old and sick were present. A 21-year-old female university student, said

“We believe we are equal to boys. It is about how one is trained. Our mothers and grandmothers never had the opportunity to do things independently, but we are a different generation. We are educated. We can understand any situation, make decisions, and act accordingly without much fear.”

In this regard, the male community members were noted to be accepting and welcoming of change with no apparent tug of power. Contrary to the differences in women perception, the responses of men from different age groups were quite alike. The similarity in the responses could be attributed to the dominant position of males in the society. Due to the patriarchal societal structure men often fail to acknowledge the underlying vulnerabilities of women. Their perception was based on the obvious societal developments and progress. For example, during the interviews, men admired the development and empowerment of women in Hunza Valley. Mukhi of Sherabad said:

“Women now days are more competent than men. If they are surpassing men in different fields, including disaster management, there is nothing wrong with it. If anything, we appreciate and encourage our daughters.”

Older women also acknowledged that education provides opportunities to women such as confidence, knowledge and livelihoods that help them in decreasing their overall vulnerability. An old woman whose daughters are now college students said,

“Women who are educated have a better sense of the world. They are less vulnerable. They have the knowledge and education, and courage to face any unfavorable situation. The same is true for women who are financially independent. It is the uneducated, who face so many difficulties.”

The results show that the perception regarding the gendered vulnerability of women is changing. Factors such as education, employment, mobility, and decision making combined with formal emergency trainings are decreasing the vulnerability of women.

3.2. Gendered Access to Assets and Resources

Assets and resources include both tangible and intangible resources such as information, decision making, and mobility, etc. In this study, three main assets and resources were identified namely information, communication, and post-disaster sanitation situation. The societal layout prior to any hazard event determines the access of women to these assets and the level of vulnerability it will likely produce. Bradshaw and Fordham (2013) wrote that the global situation of women’s access to resources (in comparison to men) is poor, including income, education, health, and social networks [

35]. We are taking the liberty to address some of these resources (such as health, sanitation, and education) under other themes as they signify other important disaster-related aspects of societal fabric.

The literature shows that women are more likely to seek disaster related information, take precautionary measures and prepare for emergencies than men [

23]. In Hassanabad, women were very vocal about the hindrances they faced during the Shishper flood event. Women primarily based their social and climatic knowledge on their lived experiences and their ancestral knowledge [

36]. As the Shishper glacier surge in 2017, women received glacier-related information indirectly via their male family members, informal meetings among women in the neighborhood where they exchanged information, online social networks such as Facebook and WhatsApp or through Jammat Khana. There is a wide spread use of smart phone technology in Hassanabad especially among the youth. The women who were less technologically savvy preferred to use simple mobile phones, however almost every household had smart phone users. We will analyze all three sources, one by one. The interviews of women showed that they strived to achieve a complex balance between their desire for more involvement and direct access to information and their trust in the most common information mediums that are their male family members and Jammat Khana. The women acknowledged that the information they receive was filtered as the male family members chose to re-tell the information they deemed important. A housewife, 50, whose sons have a dry fruit market in the central village of Aliabad, said

“My son goes to the shop [in bazaar], meets other people, and we have a discussion later. We [women] stay home all day that’s why we have less information. It would be really good, if I get the information and updates directly but my brother-in-law works with AKAH as a part of the community emergency team. During the Shishper event, he took pictures of the site and showed me on his laptop. I am satisfied with the information I get.”

Ikeda (1995) argued that the social isolation of women during normal times restricts women from acquiring relevant and necessary information on risk minimization [

37]. The theoretical debate of gender and public /private sphere, i.e., “The public sphere as male and the private sphere as female,” dictates the social situation in our case study as well. Marshall and Anderson (1994) stated that the gendered segregation of public and private spheres has its roots first in patriarchy and later in capitalism [

38]; however, we argue that in Hunza Valley, further amalgamation of cultural and religious connotation made it quite a complex system. In Hassanabad, women considered the indirect information reception as a viable method because they wanted to show their trust in the male family members. Most of the time, women tend to agree with the information they receive. The women in Hassanabad were also unable to participate in hazard and risk related discussion due to a lack of proper knowledge and in-depth information. Men, on the other hand, were not bound by any customary practices and mobility restriction; therefore, they had direct access to multiple sources of information. A majority of the men from Hassanabad conducted personal site visits to Shishper glacier to assess its behavior and flow of water. They also held numerous informal communal meetings, and attended formal meetings with District Administration, District Disaster Risk Management and Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH). A man in his late twenties told me:

“Most of the time, we try to keep ourselves updated by visiting the glaciers and observing whether it has surged or remained the same. This is a weekly visit. We also keep an eye on the weather forecast.”

A community disaster committee was also formed on the village level, which constituted village notables, including Numberdar and other senior men. There were no women members of the committee. The all-males committee organized several meetings with the district government and other high officials such as Director-General Gilgit Baltistan Disaster Management Authority (GBDMA), Governor of Gilgit Baltistan, and Commander-in-Chief Pakistan Army. During the meetings, the village committee put forth their concerns, but due to the lack of women representation, there was no discussion on women’s needs during the Shishper glacier crisis.

During the interviews, men were open to admit that women face difficulty in getting disaster-related information because of their restricted mobility and limited access to resources than women themselves. The Mukhi of Sherabad mohalla said.

“Women are usually the last ones to receive information; they probably miss out on [at least] some information.”

During the study, it was analyzed that the role of Jammat Khana was very crucial in the hazard-risk-community vulnerability nexus as it was an efficient medium of information dissemination. The circulars from AKAH containing hazard updates and necessary precautionary measures were sent to each Jammat Khana, where all the attendees (both women and men) could access it firsthand. This practice was a positive step in bridging the gendered access to information. A young married woman said

“AKAH sends circulars and it is read aloud (usually on loudspeakers) from Jammat Khana. They inform us whether there will be heavy rainfall, snow avalanche, rock fall or heat stroke in the coming days. They also give precautionary steps like stock food, or do not travel, etc. with these weather updates. The warnings give us enough time to prepare ourselves for any situation. AKAH also gives us disaster trainings. I think these steps make the communities resilient and strong in their adaptive capacities.”

AKAH has been working on building community resilience using non-structural measures such as verbal lectures, practical emergency drill, and first aid trainings for several years. These trainings are arranged in the Jammat Khana, where all men and women can easily attend. Data revealed that the number of women in emergency trainings was usually higher than men; however, women faced certain issues that hindered their learning. The dominating presence of men in trainings, both as trainers and participants, usually put women in the background. Many women claimed to feel ‘shy’, ‘uncomfortable’ and ‘hesitant’ to openly participate in trainings and drills. They admitted that during trainings, if they had a query, they chose not to ask in front of many people, especially men.

Access to Sanitation and Women Vulnerability

The third prominent area of concern was the gendered sanitation post-disaster. The women of Hassanabad have had a prior experience of living in the tent set up post a landslide induced evacuation. The tents were set where the evacuated families stayed for up to three months. Women and young girls alike reflected on the uncomfortable sanitation situation. The privacy for women was the main challenge as the facility was shared. Women were culturally and socially not accustomed to open deification, whereas men were not that strictly bound by cultural or social norms in this aspect. Women from all age groups with menstrual conditions found the tent set up to be a very uncomfortable experience especially because open discussions about menstruation are still considered a taboo in the society. In Hunza, women personally disposed of their sanitary material, and it is considered extremely unethical to throw them away with the regular waste. Such customary practices made it even more troublesome for the women to adjust to the tent setup.

One older woman in her late fifties explained it in detail

“For men, it does not matter where they live or stay, but for women, it is a problem, especially sanitation and other basic necessities. When you live in tent, men can go anywhere to wash themselves but women have restrictions. We have special needs for washroom and hygiene. There was no arrangement for women sanitation in the tent.”

During the temporary stay in tents, women were forced to come back to their homes which were physically vulnerable to a landslide only to use washrooms. Although their homes were not declared safe from the threat of landslide and this unofficial arrangement put their lives at risk, the women deemed it to be most suitable.

They added that the government monitoring team was only men, and therefore, women did not feel comfortable sharing these private issues. Women explained how menstruation and other sanitation issue are private matters, and they cannot bring them up in any forum where the recipients/conductors are males. A middle-aged housewife said

“Whenever there is a disaster warning, we make sure that we keep our personal hygienic things packed, but usually, the disaster warnings are without a timeline. It creates an issue because we do not know for how long we will need to be out of our homes.”

3.3. Hazard Vulnerability and Gendered Division of Labor

‘‘The roles that people have within the family unit play a major part in what family members do, how they behave and respond during a crisis’’ [

22]. The rural areas of Pakistan in general and the mountain region, in particular, have been agrarian, especially from the female employment point of view. Women’s engagement in agriculture depends on a multitude of factors, including socio-cultural norms, agro-ecological conditions, and migration patterns [

10]. Women are not only responsible for house chores and meeting the immediate survival needs of family members but also have to play a paramount role in agricultural activities and cattle rearing [

39]. As their contribution is often in the form of unpaid labor, it is not as actively acknowledged in society. In disaster situations, the work carried out by women increases manifold, which directly impacts their vulnerability. Out-migration by male members of the families, especially off-farm seasonal migration, is a livelihood diversification strategy that is very common in Karakoram Region. They usually move to downstream urban areas or foreign countries. In Hassanabad, there were some families where males had migrated. Women who were left behind took charge of the household, cattle, and agricultural land. However, as access to resources differs for men and women, often times, women made decisions that suit them better, such as changing cropping patterns to reduce the risk of crop failure, etc. An old man, aged 55, said

“In the old days, women used to stay at home mostly, and men dealt with outside business. The decisions were made by men, and women agreed to them, but now things have changed. If you look at different communities in Hunza, you will see men and women work side by side and with cooperation. It makes the work easier for both of them.”

In the above statement, the claim that the men and women ‘work side by side’ does not mean equal division of labor or equity of labor. In Hassanabad, the mobility of men revolved around resource procurement and management, while women remain at homes, with a more prominent role in the care economy, taking care of homes, children, and managing natural resources around the homestead. Thus, the gender division of labor was quite noticeable. A woman whose husband works in Karachi said

“There are some households where men have migrated for earning. They send remittances to their families. In such cases, women become the house heads. Women make daily life decisions, but they have to keep their husbands in the loop and cannot take a decision independently without informing their husbands. Decisions are made with mutual consent. Other times men are informed, and they take care of issues over the phone by getting in touch with other men in the village/ locality. It includes issues related to land, such as what to grow on land, land rental, hiring labors for land preparing, etc. They send money accordingly then.”

Another woman’s perspective of male migration was interesting and reflected diligently on how women perceived themselves in society. The quote below shows the strength and wisdom of women that they gain by being at the social and economic forefront. During the fieldwork, it was noticed that women rarely exhibited these qualities and usually felt comfortable behind the passive, submissive facade. This behavior was more prominent in married women as compared to unmarried girls. The unmarried girls were unhesitant to showcase their confidence and understanding of the gendered dynamics of labor in their society.

“I do not think that households, where men have migrated, are more vulnerable. Women can take care of the house. Sometimes, the men are careless by nature; my own husband is like that. They do not look after the children, nor do they pay much attention to the land. In such situations, a woman becomes stronger because she takes care of land, house, and children. It is also training. If a woman does not have so many responsibilities, she will be less vulnerable in a disaster situation. Women have to worry about too many things as compared to men.”

The above statement is from a local housewife which resonates very well with the literature where several studies have concluded that females are disadvantaged because of their domestic and agricultural responsibilities. It also shows that women take disaster risks more serious and threatening as compared to men [

25]. The female-dominated agriculture sector leaves the women responsible for almost all the farming and non-farming responsibilities of their respective households. The feminization of labor in rural households of the Karakoram region places women in a vulnerable position. During most disasters, women face an immense amount of stress being the caregiver of their families and responsible for unpaid work for households [

40]. This reality highlights the role and position of women at the forefront of mitigation and adaptation activities amidst differential access to resources, ownership, and control over critical natural resources [

10]. In Hassanabad village, it was found that although women engaged in disaster preparedness, mitigation, response, and rehabilitation strategies, their responsibilities were focused on homes and families such as managing immediate resources like water and energy, preparation and provision of food, taking care of material items, keeping the house items or family possessions safe, looking after children and other family members. During flood preparation, women ensured that the important documents (degrees, property and bank documents, national identity cards, etc.) were sent to a safe location, usually a relative’s place. Flood preparations also included stocking up on essential items in advance such as rice, flour, oil, dry fruits, and essential medication. During crises, people temporarily migrate to safe locations, taking their belongings and animals [

41]. During the Shishper flood, the female-headed houses exhibited such proactive behavior more than the male-headed households. One female head rented a house in Aliabad a month prior to the flood and shifted her important furniture and possessions because her house was physically vulnerable to the flood. Another woman also said that her family rented a house in Aliabad at the beginning of 2019 and also shifted. However, when there was no flood until June, she shifted back as the rent was putting an extra financial burden on her family. She said that the responsibility of taking care of family, land, cattle, house, and other possessions are extremely unnerving for her. She claimed that had it not been for these responsibilities, women might not be so vulnerable during disasters. She further said:

“Women spend their life building these houses and filling them with furniture and other things. It is challenging for us to leave everything and go. No matter how tough the situation is, we always want to stay till the last moment to make sure that our belongings are fine.”

The behavioral differences between men and women indicate that women are generally more inclined to participate in housebound disaster preparedness and mitigation activities than men [

25]. However in households, typically natural hazard preparedness and subsequent decision making is performed jointly by the spouses [

42], however there is a chance of incomplete or inaccurate information regarding household hazard preparedness if the spouses do not agree or communicate [

23]. In both the cases stated above, women took excessive pressure onto them and took the precautionary measure to safeguard their house as well as their belongings. However, their decision to stay close to their own homes during flood also showed their care and emotional attachment to their economic assets.

3.4. Unequal Women Representation in Formal and Informal Institutions

In every society, institutions play a significant role in shaping economic activities, which leads to the speculation that these same institutions should also have a more prominent role in disaster prevention and management [

43]. The government of Pakistan has numerous programs that facilitate climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. However, unfortunately, gender component in these programs lacks serious consideration. In Hassanabad, there are several formal and informal institutions. The lack of women representation at formal institutions such as District Administration, Hunza, and District Disaster Management Authority was obvious. There are no female employees in the whole Disaster Management Department neither at the district level nor at the provincial level. The gender imbalance at the institutional level is also reflected in disaster planning, and mitigation activities carried out by the district disaster management authority.

The women of Hassanabad village were very open in critiquing the established formal institutional setup, which neglects women’s needs, especially during different phases of disaster. Although, theoretically, both men and women are free to approach the government institutions, however, there are invisible lines dictated by cultural practices and social structures that prevent women to freely access government institutions. In Pakistan, the institutional structures and processes remain patriarchal and largely male-dominated, making women uncomfortable [

10]. The structural disaster mitigation planning by the Disaster Management Authority (Hunza) during the Shishper glacial floods was much appreciated by men, but the women pointed out their invisibility in both planning and execution phases. It shows that on the formal institutional level, the gender aspect is visibly ignored. Studies indicate that if gender is not considered during disaster relief programmes; women might become invisible in the process [

44]. The gender inequality between men and women was already evident as men not only received more resources but also had more participation in the disaster planning and implementation phases. A young woman who had children under the age of five said:

“If the government would arrange disaster-related trainings specifically for women, tell them about safety parameters/measures and give them helpline numbers that would be very good. Here men are on the front foot and women are not given much attention. Men are in charge and they are included in all the tasks. I feel women should also be given some attention with regard to disaster management and training.”

ILO (2002) argued that despite having indigenous knowledge, social networks, a strong position in families, and active role in outdoor work, women are not considered as ‘front-line’ responders during crises [

31]. In Hassanabad, it was found that disaster-related trainings have had a profound positive impact on women’s understanding and perception of disasters. The young educated girls were found to be vocal and confident. For them, the hazards were not merely ‘acts of God’ and ‘guaranteed disasters—rather, they focused on the technical understanding of hazards and how they can be safe. A young girl, who goes to university in Lahore, said

“Education plays a vital role in determining the vulnerability of women. An educated girl is sensible and understands a situation in-depth, rather than taking things superficially or only at their face value. Like in this recent flooding event, the women were very much ready to take care of children and elders. The girls were on flood monitoring duty with the boys, they were actively going into homes to tell the people flood situation. Looking at that, I feel that girls are equal to boys. It is true that education enables women to act better, and educated women consider themselves safer than those who are not educated.”

The above statement reflects how education is playing a vital role in changing the narrative around women’s vulnerability and is gradually reducing the gender vulnerability gap. The data showed that education did not only empower women in terms of economic opportunities but also boosted their self confidence. During the interviews, the young women in Hassanabad clearlt stated that they are less vulnerable to the hazards as compared to their mothers ot grand mothers. The girls highlighted that due to their education, they are not only able to face unfavorable situatiions with confidence but also have the ability to take timely decisions.

The women above 40 years generally had no formal education. Despite that, they all recognized the importance of education in terms of financial security, decision making, and confidence. They also deemed education important in a disaster context, relating it with the disaster perception and the attitude towards natural hazard occurrences. One woman in her late 40s said:

“The girls who are educated are completely different from us. They have confidence and the skill to manage emotions in the time of trouble. Their decision power is also better, which helps them be less vulnerable.”

However, there are several issues that women pointed out that create hindrances for them, such as language barrier, male trainers, unified training sessions, etc. Mostly married women were more critical of this arrangement as the young girls lacked experiences of pregnancy, childbirth, postnatal complications, and other issues. A married woman in her early thirties explained it in detail. She had a graduation degree but was not employed.

“The trainings do not have any segment on women. There is no discussion about what to do if a woman is pregnant or sick. Two to three weeks before the flood, a team from Aga Khan Health Service came here and took data regarding the pregnancies or sickness or inabilities, elders. They said that in case of an emergency, we will evacuate you. People rely on external help a lot now. When there is a landslide or flood, teams come and collect data and take pictures. The community then waits for them to do something regarding this. They say that if they have collected the data and taken pictures, they will do something about it.”

During regular time, there was significant women representation and participation on a communal level, but disaster planning lacked women’s presence and also did not cater to women’s needs exclusively. A notable community member admitted that the disaster plans they made on the community level regarded the household as a unit and all people as equal. Even though there were some general clauses that recognized women, children, and the elderly as more vulnerable, there was not any separate section on women’s specific vulnerabilities. One of the male notables of the Hassanabad community said:

“When we plan, we plan as a community, we do not plan separately for women or do not discuss women related issues separately. I know there are many areas where women need more attention to decrease their vulnerability. Maybe the women did some discussion and planning for themselves separately and did not share with us, but otherwise, we did not cater to any women-specific needs in our plan. I feel like it was our mistake.”

In Hassanabad, the women have a local and informal village-level set up called Tanzeem. It is a women-based organization which provides women with a an opportunity to own a savings account from their personal income. It is one of the most common and widely used women’s social network. It is headed by a president and has a financial secretary or treasurer who keeps records for all the accounts. During the Shishper flood, women who were part of the Tanzeem discussed the looming threat among themselves. One of the members said:

“We discuss the natural hazard among ourselves. We offer to help transport people’s possessions from one place to another or provide first aid to someone in case of a casualty. We have been trained to give first aid. The majority of the community members are trained, including women, to do bandages and CPR. We were also taught to make use of the available local resources for treatment if there is no first aid kit available at the spot, e.g., use chaddar [a garment women use to cover themselves] as bandages.”

Unfortunately, Tanzeem is not recognised as a viable platform by the formal institutions to address women’s disaster related vulnerabilities and issues.

Through this above account, it is clear that although women are not very visible on government level formal institutions but on the communal and grass-root level, the presence of women is quite strong. The adaptive capacity, resilience, and knowledge that women in Hassanabad gained through experience is often times overlooked by their male counterparts and the governmental authorities who work towards disaster mitigation. Women who are left out suffer more during the disasters as they lack resources and sometimes the confidence to act upon their intrinsic knowledge. In Hassanabad, the women underestimated their skills and strength and multiple time and quoted multiple times that they cannot function without men during a crisis. The community capacity building programmes must be gender-sensitive, as this can create a difference between life and death. Moreover, the involvement of both men and women in disaster planning and mitigation can considerably reduce the impacts of natural hazards on the communities [

44].

3.5. Women Mobility, Safety, and Vulnerability

Ferdous and Mallick (2019) talked about the discriminatory cultural norms and practices such as lack of property ownership, lack of education, early marriage, the dowry system, and acceptance of domestic violence against women, which shape gendered vulnerability and make women more vulnerable in the disaster situation [

45]. These norms and values are often based on different risk perceptions. Women’s mobility and economic empowerment are also incapacitated by these discriminatory social norms. In the Shishper flood scenario, the discussion regarding women’s mobility before and after the disaster situation was quite interesting. Typically, women’s mobility within Hassanabad or nearby village settlements is neither restricted nor monitored. They do not observe any strict

purdah (in the strict interpretation of Islamic law, the women observe a veil covering their faces. They do not show their faces to men outside their immediate families), albeit they are modestly dressed. The communication between the men and women of the same village is often times smooth and non-problematic as people share a mutual trust and comfort among themselves. Before the Shishper flood, a few families moved from Hassanabad to Aliabad, mostly because of the flood. However, there was one family which did not move solely because of the flood. The women lived in Hassanabad with her children. Her husband had migrated to a city downstream. She said:

“There are six houses in my neighbourhood. Before the flood, people evacuated their houses and moved to Aliabad. We also moved but not only because of the threat of flood. There were some non-local people building a slaughterhouse nearby. I used to be alone in the house after my children went to school. My family felt unsafe and therefore we decided to move.”

They shifted back to their own house after the non-local labors went back.

The mobility pattern of women in Hassanabad is changing quite rapidly, especially because women are actively participating in education and economic sectors. Women from Hunza Valley have also travelled abroad for education, sports, and job purposes. The Mukhi of Hassanabad said

“Women in Hunza have a lot of freedom to move about for work and education. The families know about the detail of their travel, but it is not necessary for them to be accompanied by a male member. Women here drive as well without any restriction now. They are free to move forward in life. Women also go abroad, and their families, brothers and fathers support them. We want to see them progress.”

The above statement depicts the status of women in the rural society. However, when the discussion was framed in a disaster situation, another narrative represented the underlying societal boundaries that dictate women’s behavior and choices. The same Mukhi said:

“In case of danger, a man can take refugee with the nearby army camp or with police, but a woman cannot do this. She will go not to a ‘ghair mehram’ (a stranger man) for help, even if she has to lose her life. She will not prefer to ask help from a stranger. This is another instance where women are more vulnerable. Of course, this mindset that a woman’s honor is more valuable than her life is propagated by men. They create these norms and narratives in society. “

The contradiction in the positioning of women in society showed the complexity of the relational and situational context of women and patriarchy. Women in Hassanabad did not entirely agree with this arrangement. A woman in her late 50s said that:

“We are all human beings first, and one must put humanity first. All the security departments, be it army or police, they are here for us. They have respect for us. They are here to protect us like their own sisters and mothers. We should also treat them with respect as we treat our fathers and brothers.”

Counter arguing the position of women and their notion of honour, the Mukhi added:

“I am personally not in favour of ‘purdah’—why should the women do purdah? Men should respect them and in a way that there is no need for any purdah (in the form of burqa). But as men, we are always scared for our sisters and daughters. Whenever my daughter travels alone, I worry about her safety. She might feel that her father does not trust her or she is weak. So if you analyze I am propagating a mindset. If, instead of this, we give them the confidence to go ahead and not worry about anything going wrong, that would be better. I am also part of the problem here.”

Here the word

purdah is used quite loosely, mostly meaning avoiding unnecessary interaction with men and random visits to market places or other villages alone. The shift of the right and wrong and the scale of permissible and non-permissible during a disaster situation is incredible. The societal parameters of judgement for women switch, and men encourage women to take all the possible actions that might save their lives during a disaster. Saad (2009) also stated that during a crisis and immediately after that, the gender difference tends to temporarily disappear; however, once the situation settles, women suffer greater consequences as they lose their privacy and income opportunities [

46]. One of the respondent men said:

“Purdah is not valid in the time of disaster. For example, if there is a flood and people are suffering at a community level, then police, army, or other volunteers are there to help. The helpers also do not care whether it is a man, woman, or elder that they are helping. That is why nobody thinks anything negative in these troubling situations.”

Similarly, the females usually do not prefer to engage in conversation with men who are strangers, but during the crisis situation, the social norms suspend (for the time being). The male respondents believed that during disaster situations, women became “fearless” and asked for/took help from any available source, especially the young girls. The Captain of the Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) said:

“In normal times, women do not talk to strangers. But the other day, when the District Assistant Commissioner came in a disaster preparedness meeting, the young girls had a discussion with him which they would not have in a normal situation.”

The women of Hassanabad, especially the housewives disagreed with this narrative. They said that the hesitation women feel does not automatically disappear in crisis situation. The trainings that women and men of Hassanabad get in the Jammat Khana and the community meetings do not explicitly address that women have mobility and communication barriers in a normal situation, which can cause an increase in women’s vulnerability during disaster situations. The village Mukhi shared a broader perspective related to women’s safety, honour and vulnerability during disaster situations.

“If any woman does not ask for help in desperate times, I feel that the fault is at both ends. Although she should leave no stone unturned to save her life as a society, it is also our fault. We have created and propagated a negative mindset around female honour. Even during our disaster planning phase, we have never considered certain concepts in our society that might be harmful to women, and we should actively address them. Never in a meeting have we declared that everyone should seek help if their life is in danger regardless of who is providing help.”

The in-depth interviews with men of Hassanabad from different age groups brought the discussion around to these sensitive social and religious topics. The male respondents admitted that during disaster planning and mitigation, women are not given due consideration as a separate vulnerable group. During the discussion, our male respondents referred to women as their equals who are sometimes prejudiced against as a customary practice. Moreover, they implied that women are not discriminated against consciously, but rather the cultural practices are being replicated by the men and women of the community.