Human Resources Management Practices Perception and Extra-Role Behaviors: The Role of Employability and Learning at Work

Abstract

:1. Introduction

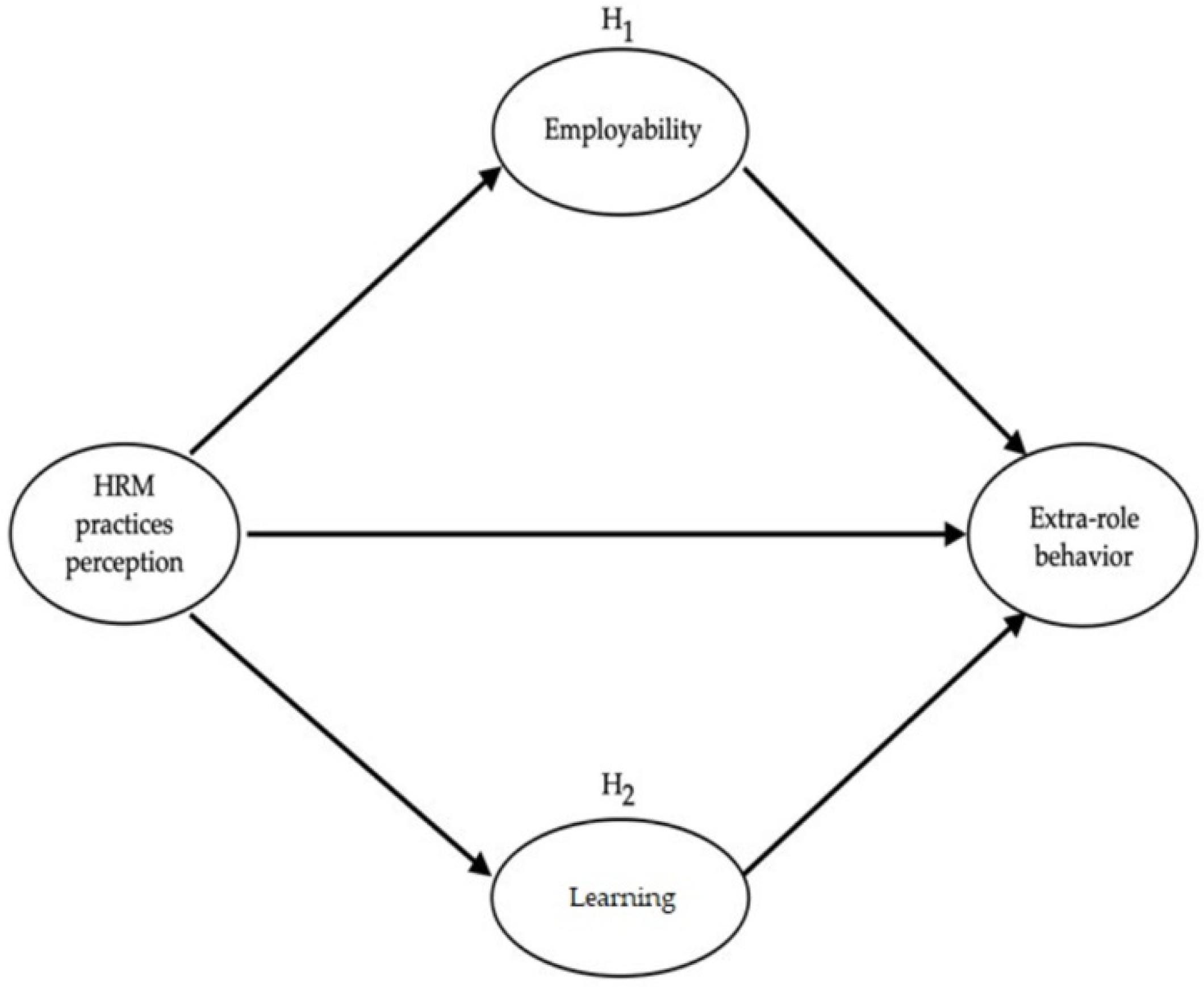

1.1. Employability as a Mediator of the Relationship from HRM Practices to Extra-Role Behavior

1.2. Learning in the Workplace as a Mediator of the Relationship from HR Practices to Extra-Role Behavior

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walton, R.E. From control to commitment in the workplace. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1985, 63, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, T.; Lydka, H.; Fenton O’Crevy, M. Can Commitment Be Managed? A Longitudinal Analysis of Employee Commitment and Human Resource Policies. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 1993, 3, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Bierman, L.; Shimizu, K.; Kochhar, R. Direct and moderating effects of human capital on strategy and performance in professional service firms: A resource-based perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, B.; Gerhart, B. The impact of human resource management on organizational performance: Progress and prospects. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 779–801. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, L.; Reeves, T. Human resource strategies and firm performance: What do we know and where do we need to go? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1995, 6, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, P.M.; Dunford, B.B.; Snell, S.A. Human resources and the resource based view of the firm. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delery, J.E.; Doty, D.H. Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 802–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huselid, M.A. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 635–672. [Google Scholar]

- MacDuffie, J.P. Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: Organizational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry. ILR Rev. 1995, 48, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.; Liu, Y.; Hall, A.; Ketchen, D. How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Gardner, T.M.; Moynihan, L.M.; Allen, M.R. The relationship between HR practices and firm performance: Examining causal order. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 409–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J. New Perspectives on Human Resource Management; Routledge: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gould-Williams, J.; Davies, F. Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of HRM practice on employee outcomes: An analysis of public sector workers. Public Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marchington, M.; Grugulis, I. ‘Best practice’ Human Resource Management: Perfect opportunity or dangerous illusion? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 11, 1104–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Qun, W.; Abdullah, M.I.; Alvi, A.T. Employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility impact on employee outcomes: Mediating role of organizational justice for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Sustainability 2018, 10, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, P.M.; Boswell, W.R. Desegregating HRM: A review and synthesis of micro and macro Human Resource Management Research. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 247–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, M.; Romero-Fernandez, P.M.; Aust, I. Socially responsible Human Resource Management and employee perception: The influence of manager and line managers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. The impact of organizational citizenship behavior on organizational performance: A review and suggestions for future research. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Budhwar, P.S.; Chen, Z.X. Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R. The Social Psychology of Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In Personnel Selection in Organizations; Schmitt, N., Borman, W.C., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Gevers, J.M. Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Parker, S.K. 7 redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 317–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Crafting the change: The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1766–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Harten, J.; De Cuyper, N.; Guest, D.; Fugate, M.; Knies, E.; Forrier, A. Special issue of international human resource management journal HRM and employability: An international perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 2831–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forrier, A.; Verbruggen, M.; De Cuyper, N. Integrating different notions of employability in a dynamic chain: The relationship between job transitions, movement capital and perceived employability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, A.; Arnold, J. Self-perceived employability: Development and validation of a scale. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingusci, E.; Ripa Montesano, D.; De Luca, K.; Iacca, C.; De Giuseppe, M.C.; Varallo, F. Employability e job crafting: Nuovi sviluppi per la ricerca. In “Work in Progress” for a Better Quality of Life, Proceedings of the Conference Work in Progress for a Better Quality of Life, Lecce, Italy, 6 June 2016; Ingusci, E., Tanucci, D., Ripa Montesano, D., Eds.; Milella: Lecce, Italy, 2016; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffers, J.; van der Heijden, B.; Schrijver, I. Towards a sustainable model of innovative work behaviors’ enhancement: The mediating role of employability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forrier, A.; Sels, L. The concept employability: A complex mosaic. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2003, 3, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricout, J.C.; Bentley, K.J. Disability status and perceptions of employability by employers. Soc. Work Res. 2000, 24, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, D. From full employment to employability: A new deal for Britain’s unemployed? Int. J. Manpow. 2000, 21, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, L. Defining and measuring employability. Qual. High. Educ. 2001, 7, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntson, E.; Marklund, S. The relationship between perceived employability and subsequent health. Work Stress 2007, 21, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntson, E.; Sverke, M.; Marklund, S. Predicting perceived employability: Human capital or labour market opportunities. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2006, 27, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M. Understanding and managing employability in changing career contexts. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2008, 32, 258–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J. A dispositional approach to employability: Development of a measure and test of implications for employee reactions to organizational change. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 81, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirves, K.; Kinnunen, U.; De Cuyper, N.; Mäkikangas, A. Trajectories of Perceived employability and their associations with well-being at work. J. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 13, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Tims, M.; Beijer, S.; De Cuyper, N. Should employers invest in employability? Examining employability as a mediator in the HRM–commitment relationship. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A.M. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Spreitzer, G.; Gibson, C. Antecedents and consequences of thriving across six organizations. Presented at the 2008 Academy of Management Meeting, Anaheim, CA, USA, 8–13 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Porath, C.L.; Spreitzer, G.; Gibson, C.; Garnett, F.G. Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frazier, M.L.; Tupper, C.; Fainshmidt, S. The path(s) to employee trust in direct supervisor in nascent and established relationships: A fuzzy set analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Misati, E. Does ethical leadership enhance group learning behavior? Examining the mediating influence of group ethical conduct, justice climate, and peer justice. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 72, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Wang, S.; Weadon, H. Thriving at work as a mediator of the relationship between workplace support and life satisfaction. J. Manag. Organ. 2020, 26, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G.; Sajjad, I.; Elahi, N.S.; Farooqi, S.; Nisar, A. The influence of prosocial motivation and civility on work engagement: The mediating role of thriving at work. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1493712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbasi, A.; Porath, C.L.; Parker, A.; Spreitzer, G.; Cross, R. Destructive de-energizing relationships: How thriving buffers their effect on performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, U.R.; Mishra, M.K. Impact of high performance HR practices on organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and turnover intentions of insurance professionals. Psyber News 2018, 9, 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kuo, M.H. Examining the relationships among coaching, trustworthiness, and role behaviors: A social exchange perspective. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2015, 51, 152–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, B.; Ali, M.; Ahmed, S.; Moueed, A. Impact of managerial coaching on employee performance and organizational citizenship behavior: Intervening role of thriving at work. Pakistan J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2017, 11, 790–813. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, B.; Cardona, P.; Ng, I.; Trau, R.N. Are prosocially motivated employees more committed to their organization? The roles of supervisors’ prosocial motivation and perceived corporate social responsibility. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2017, 34, 951–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettner, S.L.; Grzywacz, J.G. Workers’ perceptions of how jobs affect health: A social ecological perspective. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, A.K.; Rudolph, C.W.; Zacher, H. Thriving at work: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 973–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Škerlavaj, M.; Štemberger, M.I.; Dimovski, V. Organizational learning culture—the missing link between business process change and organizational performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2007, 106, 346–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.; Levenson, A.; Finegold, D.; Chattopadhyay, P. Extra-role behaviors among temporary workers: How firms create relational wealth in the United States of America. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 530–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive | Correlations | Reliability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | CR | AVE |

| 1. HRM practices perception | 3.05 | 1.31 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.53 | |||

| 2. Learning | 3.45 | 1.10 | 0.530 ** | 1 | 0.87 | 0.64 | ||

| 3. Employability | 3.18 | 1.24 | 0.400 ** | 0.318 ** | 1 | 0.88 | 0.59 | |

| 4. Extra-role behavior | 3.79 | 1.16 | 0.361 ** | 0.428 ** | 0.365 ** | 1 | 0.90 | 0.71 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pace, F.; Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Sciotto, G. Human Resources Management Practices Perception and Extra-Role Behaviors: The Role of Employability and Learning at Work. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168803

Pace F, Ingusci E, Signore F, Sciotto G. Human Resources Management Practices Perception and Extra-Role Behaviors: The Role of Employability and Learning at Work. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168803

Chicago/Turabian StylePace, Francesco, Emanuela Ingusci, Fulvio Signore, and Giulia Sciotto. 2021. "Human Resources Management Practices Perception and Extra-Role Behaviors: The Role of Employability and Learning at Work" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168803

APA StylePace, F., Ingusci, E., Signore, F., & Sciotto, G. (2021). Human Resources Management Practices Perception and Extra-Role Behaviors: The Role of Employability and Learning at Work. Sustainability, 13(16), 8803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168803