Abstract

To survive in the current competitive era, organizations need continuous performance and development. The performance of any organization is linked with their employees’ performance. However, employees give their best when they see subjective career success in the organization. There are certain factors such as work–family enrichment (WFE) that affect employee’s subjective career success. The purpose of this research is to investigate the relationship between work–family enrichment and subjective career success through the mediating effect of work engagement. The data for this study were collected from various private banks located in a large metropolitan city through a self-administered questionnaire. The data were analyzed through the structural equation modeling (SEM) method. The results confirmed that work–family enrichment (WFE) positively affects subjective career success (SCS), and job engagement (JE) completely mediates this relationship. These findings will be helpful for banking sector policymakers to improve the subjective career success of personnel at the workplace through WFE and JE.

1. Introduction

Career setting has transformed throughout the previous couple of years because of the swiftly changing and vague environment. Firms have experienced changes to compete with environmental instability and meet market demands. Globalization and technological improvements are causes of rapidly dynamic market requirements [1,2]. The business world has become competitive enough that every firm is striving to secure its market share. Ultimately, the banking industry is also influenced by this phenomenon [3]. Now, this sector is also becoming more competitive. Work operations of banks have changed drastically because of mergers, acquisitions, downsizing, and technological enhancements [4]. Employees of banks have a greater urge to develop their careers than before. However, the prime objectives of the banks are to maximize revenues and profits, gain a competitive edge over competitors and increase customer satisfaction [5]. Financial institutions are nominated as more stressed as compared to other sectors in Pakistan [6]. Employees have to work for long hours, feel more pressure, and have to become experts in modern technologies. They feel difficulty in maintaining balance between work and life due to their highly demanding jobs.

Career success is an accomplishment of anticipated job outcomes in one’s work encountered over time [7]. Career success has twofold perspectives such as workers’ distinct achievement can ultimately influence organizational attainment [8,9]. Therefore, scholars, for instance, Wayne et al. [10], Boudreau, Boswell & Judge [11], Seibert et al. [12], Savickas [13], and Kraimer, Greco, Seibert, & Sargent [14], point out personal and organizational facets which help employees’ career success. This construct is conceptualized by objective career success, i.e., salary or pay, number of advancements [8], or professional rank [15]. It is also hypothesized via subjective career success denoting to person’s perception of accomplishments in a career [16,17]. The objective results of a career have been assumed abundant consideration in the past, although subjective points of view (career satisfaction) have not been studied frequently. Usually, when individuals feel that work has a positive impact on their family lives, then they are satisfied emotionally and psychologically. Nonetheless, researchers have been giving much attention to the work–family perspective for the last twenty-five years. Now, the work–family conflict is accepted as negative, whereas another positive emergent perspective is work–family enrichment. This refers to a segment that proficiencies in one role can convey positive experiences and results in the second part [18,19]. Work–family enrichment must also be observed as significant for organizations and employees [20]. Various studies have found antecedents of work–family enhancement [1,21], yet the discoveries do not provide complete knowledge of its results and association with career success amongst both genders [19,22].

Work engagement is one of the most popular areas in organizational science [23]. Work engagement is an affirmative, substantial topic brimming with the motivational condition of job-related success, which is delineated by power, responsibility, and assimilation [24,25]. Organizations need employees who are vigorous, energetic, and consumed by a job that is connected to their work [26]. Family and work-life are important arenas that affect each other; for example, the job can disturb family life. So, work– family conflict may reduce job satisfaction [27]. Furthermore, employees have to play specific parts such as employee and fathers concurrently, and such roles conflict with each other. Usually, research focused upon work–family conflict and employee problems is connected to taking part in various roles [28]. Allen, French, Dumani, & Shockley [29] made thorough endeavors to clarify the connection amongst work–family antecedents, its conflict, and its strains. Scholars contended that there may be an affirmative connection amongst the family and work parts of people’s lives through positive outcomes for role effectiveness [28].

Work and family conflicts are linked to an individual’s family welfare, work domains, and influence aspects of lifespan, for instance, family as well as marital life, job contentment, and work stress [30]. Research shows that the work–family balance has critical implications on people, firms, and eventually on the general public [31]. Work–life balance seeks to obtain an adequate level of fulfillment at home and work equally [32]. Generally, researchers argue that work–life balance is a matching of individual and household life with paid work [33]. The work–life balance paradigm is based on the notion that an individual’s life and work harmonize each other to bring precision to his life [34]. The attention of researchers is currently more towards investigating qualities and welfares of the work and family interface as opposed to its shortcomings [35]. Consequently, the objective of the current study is to look at the positive conditions among work and family roles to investigate the connection between subjective career success and work–family enrichment of the financial sector workforce in Pakistan. However, the mediating role of job engagement between these variables is also measured.

This research devises an important role in career literature. A prosperous career is a growing prerequisite for males and females everywhere throughout the world in addition to Pakistan because of dynamic economic and market demands. Pakistan is a society of male dominance [36,37]. It is a social norm that men are responsible for work outside whereas women take care of household responsibilities, for instance, cooking and the upbringing of children. The banking industry of Pakistan is male dominant, similar to other professions. Prior studies on family and work were conducted mostly in the health service sector [20,38,39,40,41,42] and a deep investigation of the literature reveals that the present study in the context of the financial sector, such as the private banks of Pakistan, still lacks quantitative and qualitative explanations. Despite the significant contribution of many studies, such as [19,43,44,45,46,47], few have examined both the main and interaction effect of work–family enrichment upon subjective career success within the work engagement framework. Similarly, there have been no previous studies that attempted to investigate the mediation effect of job engagement in a single framework. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: the next part elaborates related literature to form hypotheses and the research framework of the current study. The methodology and results segments cover the sample, data collection, instrumentation of the present study, and how the data was collected in detail. Lastly, in the final part, the paper exhibits the discussion section, which contains the implications and limitations for future research.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

The present study seeks support from social exchange theory [48], the theory of role accumulation [49], work–family enrichment theory [19], and conservation of resources theory [50] to formulate hypotheses. Therefore, this research argues that when organizations support their employees positively, then they feel ownership and make efforts to achieve organizational objectives. Thus, employees who observe their firm as being supportive of them managing both work and home roles might have a commitment to return in the shape of more affirmative emotions regarding their jobs and achieve subjective career success [51]. In the same way, work–family enrichment theory explains that family and job facets have a bidirectional relationship. According to this model, work roles influence family roles positively, and household obligations also affect job roles in the same manner. Hence, this research asserts that the workforce considers that their job and family are interlinked affirmatively. In addition, such relation boosts work devotion and immersion. Different scholars employed work–family enrichment theory to comprehend the contribution of enrichment towards job engagement [52,53]. Likewise, the conservation of resources theory contends that people tend to defend, hold, and accumulate resources (both intrinsic and extrinsic) that are worthwhile and helpful to achieve higher-order goals, fulfillment, and emotional well-being [54]. Thus, job engagement predicts subjective career success significantly [55,56].

The work–family interface has grabbed the attention of researchers in recent years. Research indicates that work–family balance has important inferences for individuals, companies, and ultimately society [44,57]. The work atmosphere may affect the nonwork-related circumstances of staff, as well as personal factors, which can influence job environment, which is known as the work-to-family or family-to-work interface [58]. In such an environment, the workforce tends to focus on leisure time, social contact with fellows, relatives, and neighbors. Organizations may improve work–life balance by allowing employees more mobility, autonomy, and job protection when they match their official tasks with life aspects [34,59]. Researchers prefer to use this concept as the work–life interface [60]. Studies have revealed that work–life balance has positive outcomes for employees, such as job satisfaction among nurses [61,62]. Likewise, work–life balance influences faculty’s performance positively and significantly through the role of job fulfillment [63]. However, according to prior examinations, the intersection among work and family is mostly dedicated to an adverse viewpoint, i.e., work/family conflict [64]. On the other hand, numerous research has studied the affirmative relationships of the work–family interface. Now, scholars pay more attention to discovering the strong points and advantages of the work–family interface instead of its flaws [21]. The theory of affirmative interdependence occurs among work and family roles using constructs such as enrichment, facilitation, enhancement, and positive spillover. Although, these paradigms are somewhat dissimilar from one another but are still positive. Scholar believe that enrichment is diverse as opposed to other concepts: as they perceive it, enrichment goes beyond positive spillover and incorporates supplementary resources, for instance, social capital, which is not part of such an affirmative construct [65,66]. In addition, enrichment is diverse from facilitation as it significantly affects systems, whereas enhancement influences people [67]. The greater stress for choosing enrichment (a positive approach) over conflict would improve knowledge of the work–life interface and will perform an essential part in a study that emphasizes the conflict approach [68]. Furthermore, this method concentrates on people but not the system. However, it is important to comment that individuals support systems, so they are more valuable resources for organizations.

Work–family advancement is considered the degree to which experience of a part improves individual satisfaction in the second role [19]. Carlson, et al. [69] clarified WFE as family roles that take advantages due to work parts by developmental assets, affirmative effects, and emotional capital derived from contribution in the job. Furthermore, scholars outlined family–work enrichment (FWE) such as job parts benefitting because of family roles through formative resources, the positive effect, and enhanced productivity received from family participation. Work–family improvement is additionally bidirectional, which means work–family enhancement (WFE) occurs when benefits from a job are valuable for a family. Likewise, family–work enrichment (FWE) happens where the advantages of a family may enhance work [44,68]. Greenhaus and Powell [19] proposed a work–family enhancement model to explain its process. The model clarifies two systems, i.e., the instrumental and emotional paths by which resource exchange occurs from one role to the second role. The instrumental mechanism is characterized as the transmission of assets that happens directly from one part to the second part. While the emotional path refers to resources produced in one part promoting positive impact in one part that at last makes positive influence in the second role [40]. Lu [46] directed Chinese longitudinal research on work–family advancement and discovered a connection between WFE and career satisfaction. He likewise concluded a relation between FWE and family fulfillment. Scholars such as Edwards & Rothbard [70] have observed a connection between work and family while assuming their significant role to clarify this relationship.

The literature recommends that work–family enhancement may help in the assessment of workers’ career success [71] since the careers of people have been significantly influenced either affirmatively or negatively through work–family conflict [72]. The exchange of resources occurs in work–family enrichment, which might be supportive for the career accomplishment of the people. Many researchers have emphasized the relationship between work–family balance and career achievement [1,40]. Similarly, the study demonstrated that work–family facilitation was positively connected with job fulfillment [73]. Work–family enrichment is interlinked to family as well as job-related results and eventually promotes subjective career success of personnel [74,75].

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

“Work–family enrichment significantly affects subjective career success”.

Some studies consist of factors that support the positive relationship among work–family roles and most of them favor job engagement. For instance, Grzywacz and Smith [76] mentioned facets that helped role development such as decision self-sufficiency and family support that related to positive spillover amongst work and family. A significant connection is observed between work engagement and the two-path process underlying work–family enhancement [21,77]. Moreover, they identify that involved employees think their work is imperative and can shape up knowledge, expertise, and diverse resources, which in turn are readily moved to their family domain. Consequently, according to these authors, just the presence of work and family resources might not lead to work–family enrichment; nevertheless, they can be used to improve job engagement and ultimately support WFE. The most imperative concept to work–family enrichment is moveable job-related possessions and work–family enrichment will probably happen when resources in one domain are useable and might be utilized in other areas [41].

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Work–family enrichment significantly affects job engagement.

Bakker and Demerouti [78] described that engaged workers often have an exposure of positive feelings, for instance, satisfaction, pleasure, and energy; experience better wellbeing; produce their job and individual resources; and furthermore, transfer their engagement to other co-workers. Cheerful employees are more sensitive to opportunities at the job, are more active, are more cooperative with fellows, and more confident and optimistic [55,79]. Job engagement has a strong association with work performance [80,81]. Well-engaged workers accept challenges and believe that they will continuously learn and grow from their work [82,83]. Engagement is also linked to career development [84,85].

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Job engagement significantly affects subjective career success.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Job engagement mediates the relationship between subjective career success and work–family enrichment.

3. Methodology

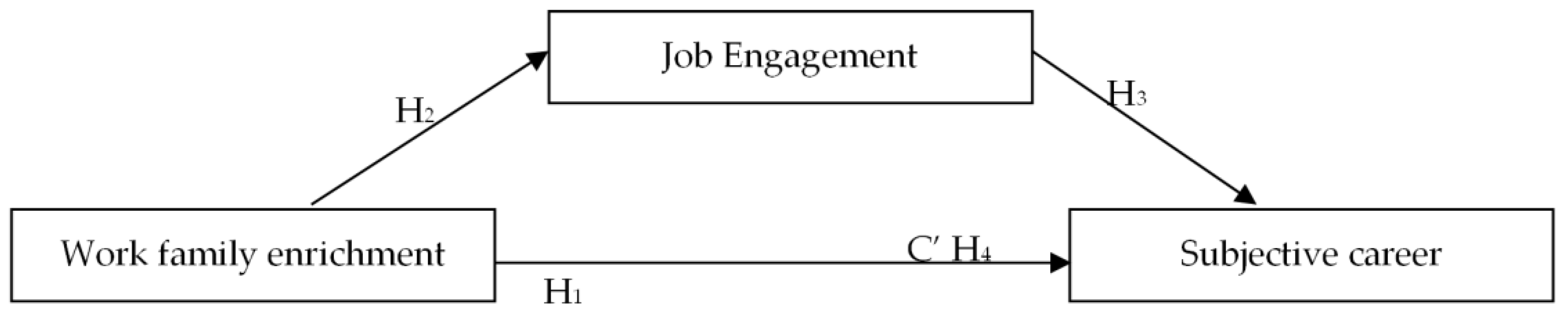

The target sector to analyze the hypnotized relationships (Figure 1) for the present research is the banking sector of Pakistan. To represent the financial sector, the researchers purposefully nominated the five largest private banks from the city of Lahore, which is the second-largest metropolitan in the country. The selected banks include Habib Bank Limited, United Bank Limited, MCB Bank, Allied Bank Limited, and Bank Alfalah Limited. The reason for choosing these banks lies in the fact that all of these have the largest branches in Pakistan and Lahore as well. Similarly, these banks have thousands of staff. The city has a huge population of corporate employees and particularly bankers who are striving to build their careers in this sector. They have their feelings, attitudes, and behaviors similar to other organizations and may need to be researched.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model, conceptualized by the researchers. This model consists of three variables: work–family enrichment (WFE) = the independent variable (X), Job Engagement (JE) = the mediating variable (M), and subjective career success (SCS) = the dependent variable (Y).

The sampling frame was available for this study, but accessibility was a serious concern. When the lists of employees working in banks were requested to HR departments of main branches, they turned down the request to provide the particulars of their workers. Employees’ privacy and security are obstacles to obtaining the complete list of all personnel working in banks. Thus, researchers do not have access to the list of employees. Nevertheless, HR departments permitted the researchers to collect data from employees. The researchers requested the HR departments of the main branches to suggest branches from where the data might be collected conveniently. However, before starting the actual data analysis segment, the authors communicated with the human resource executives of the nominated banks to seek their assistance and approval to collect the data from their workforces. The authors also signed a contract with the ethical bodies of these banks to keep ethical standards in the procedure of data collection. Moreover, the authors obtained informed agreement from all respondents to take part in the survey voluntarily. Unfortunately, the extensive COVID-19 pandemic made it difficult for the authors to collect the data from the banking staff directly as the top management of the majority of the banks did not permit the authors to keep their presence in a bank for numerous hours to gather the data. Consequently, as an alternative arrangement, the scholars, accompanied by the help of human resource representatives of the banks, requested the senior management to assign some persons within the bank who might collect the data on behalf of the researchers. In this manner, the authors asked every bank to recommend five individuals to collect the data from the selected banks. Thus, the authors provided the necessary guidance to these people on how to fill the survey. The authors disseminated a total of 500 surveys amongst these five banks and received 269 filled questionnaires from various individuals. Thus, the response rate of the current survey was about 54%. The data were gathered in two waves with a time-lagged difference of 4 weeks. The data collection process was completed during the month of January and March in the year 2021. This research was executed as per the ethical rules specified in Helsinki Declaration.

Measures and Handling Social Desirability

Current research adapted the scales from earlier prevailing studies, and so, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire were pre-tested. At this stage, to compute predictor variable (work–family enrichment) among men and women, an 18-items scale is utilized which is established by Carlson, et al. [86]. In order to, measure the dependent variable (level of subjective career success) between workforces, a scale of Greenhaus, et al. [87] is used in this research. This instrument is comprised of 5 items. Similarly, to calculate job engagement, the Utrecht Work Engagement scale of Schaufeli, et al. [88] is applied, and it has 17 items. The authors employed a five-point Likert scale for the present survey.

The authors took numerous steps to deal with the issue of social desirability. For instance, all items of the questionnaire were arbitrarily dispersed throughout the survey. The scholars performed this procedure to disrupt any order of answering the responses. Such a measure is also useful to handle the probability of any interest and disinterest for a specific concept. Similarly, the questionnaire was examined for precision and appropriateness by specialists in the field. This act is indispensable to avoid any vagueness or misperception in an item statement because of multiple or double-meaning words. In the same way, the authors cleared the data collection team to request the individuals for their accurate responses so that the results produced by their input might reflect the genuineness. Various researchers also endorse these measures to alleviate the level of social desirability [89,90,91,92]. Table 1 shows the demographic details of the sample.

Table 1.

Demographic detail.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

The researchers initiated the data analysis segment with testing for the existence of common method bias (CMB). The authors performed the CMB test as the data for all concepts in the present survey was gathered from a single respondent. Thus, to doubt the existence of CMB is not without reason. Consequently, the authors determined to discover any possible presence of CMB. As a result, the authors executed a single-factor analysis in SPSS according to the suggestion of Harman [93]. Therefore, the authors permitted all the survey items to load on a single factor. According to the guidelines of Harman, if the output of single-factor analysis confirms a single-factor that shares a variance of 50% or more, then it is indicated that the data asks for some significant consideration by the researchers to address the problem of CMB. In this context, the single-factor analysis outcomes validated the absence of any such factor that was sharing more than 50% variance. The maximum variance shared by a single factor was 38.68%, which is less than the threshold level. Hence, the authors authenticated that CMB is not a plausible concern in the present study.

4.2. Convergent Validity, Factor Loadings, and the Reliability Analysis

In the following section of data analysis, the scholars conducted various tests to confirm the reliability and validity. Accordingly, the authors, firstly, tested for convergent validity, which was validated by the statistics of average-variance extracted (AVE) for each variable. For this purpose, the authors evaluated the factor loadings of all items of a concept and observed no problem in item loadings for a variable since the loading range for all items was beyond the threshold degree of 0.5. Afterward confirming the factor loadings, the authors measured AVE for each concept by determining the sum of squares of all item loadings and then dividing it by the number of items. For instance, in the case of WFE, there were 18 items, and hence the researchers first computed the sum of squares loadings of all these 18 items and then divided it by 18. Thus, the authors determined AVEs for all concepts. The AVE statistics offer the base to determine the foundation of convergent validity as if the value of AVE for a particular variable is greater than 0.5, it is a validation that the items of that concept are converging, and therefore, the general standard of convergent validity is verified. The findings of convergent validity (AVE values) for each construct have been described in Table 2 by the authors. It is apparent from the results of Table 2 that all AVEs are beyond the threshold level of 0.5, which indicates there is no problem of convergent validity in the dataset of the current study. Similarly, the reliability results were estimated on the basis of composite reliability (C.R) statistics. The common rule to form the reliability of an instrument is that the values of C.R would be equal to or greater than 0.7. According to the statistical results stated in Table 2, there is no reliability problem since all three constructs are generating adequate values of reliability. Thus, the researchers authenticated that there is no issue of reliability in the present research.

Table 2.

Factor loading, convergent validity, and reliability results.

The researchers next conducted correlation analysis, discriminant validity analysis and the findings of the various model fit indices. These results have been described by the scholars in Table 3. According to these findings, values of correlation among all variables are affirmative and significant which shows that all the concepts of the present research are significantly correlated. For instance, the value of the correlation between Work–family enrichment (WFE) and subjective career success (SCS) is 0.638** that is positive and considerable. This confirms a positive and significant relationship between these variables. To authenticate discriminant validity, the authors computed the square root of AVE for each concept individually. After determining all square root statistics of AVEs, the researchers compared the square root value of AVE for each variable with correlation values. Consistent with the criteria of Fornell and Larcker [94], if the correlation values are smaller than square root values of AVE for a concept, the discriminant validity is established, e.g., the square root of AVE for SCS is 0.78, which is larger than the correlation value between WFE and SCS (0.638**). Therefore, in line with the recommendation of Fornell and Larcker [94], the discriminant validity criteria is confirmed. The authors also measured various model fit indices to validate the goodness of data fit. In this regard, the researchers perceived diverse model fit statistics compared to the standard threshold and discovered that the findings of model fit indices specified a good fit among theory and data. Finally, the scholars emphasized the issue of multicollinearity by checking the variance-inflation-factor (VIF). The researchers looked for assistance from the guidance of Hair, et al. [95] to infer the existence of multicollinearity in the current study. According to the criteria of Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham [95], the overall value of VIF was less than three, approving the absence of a multicollinearity problem. Thus, the authors were assured that that the problem of multicollinearity may generate any weakening impact of coefficient estimation.

Table 3.

Correlation, discriminant validity, and model fit indices results.

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

This research employed the structural equation modeling method (SEM) to verify the hypotheses. SEM is a second-generation co-variance-based data analysis method, which is preferred by the majority of modern researchers to examine the data at an advanced level [96,97,98] as this process enables scholars to estimate several interrelations at once. To estimate the hypotheses of the present research, the authors executed structural models using AMOS in three ways. In the initial phase, the scholars investigated the direct relationships suggested in hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. Therefore, the authors conducted a structural model without any involvement of the mediating variable. The findings of the direct impact analysis for hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 are stated in Table 4. In accordance with these results, the model fit statistics were in the tolerable ranges (χ2/df = 3.36, RMSEA = 0.052, CFI = 0.934, GFI = 0.931, NFI = 0.925). Moreover, the results of hypothesis 1 were statistically noteworthy (β1 = 0.63**, p < 0.001), approving that WFE positively affects the SCS of the workforces in the banking sector. Consequently, grounded on these results, hypothesis 1 is accepted. Similarly, the researchers confirmed hypothesis 2 of the present study by replicating the steps described above. In this way, the outcomes again validated that WFE positively relates to JE, approving that hypothesis 2 is also positive and significant (β2 = 0.60 **, p < 0.001). In addition, hypothesis 3 is also accepted as the findings display that job engagement influences positively subjective career success (β3 = 0.30**, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

The results for hypotheses 1, 2, and 3.

In the second phase, the authors performed a structural model to measure the mediating effect of JE between WFE and SCS. Thus, the researchers chose a bootstrapping option by selecting a large bootstrapping sample of 2000 through a bias-corrected confidence interval with 95%. The method of bootstrapping to evaluate the mediation effect is desired by numerous scholars on the conventional method suggested by Baron and Kenny [99]. This established technique was excessively disapproved by renowned scholars such as Hayes [100] and Zhao, et al. [101]. Furthermore, the Sobel test method for mediation is also opposed because of its low power as compared to bootstrapping method [102].

The findings of bootstrapping method (Table 5) verified that JE completely mediates between WFE and SCS. The authors assumed that there is partial mediation as the beta value was decreased from β1 = 0.63** to β4 = 0.18**, and it is significant (p < 0.001). Moreover, the model fit indices statistics were also enhanced, in contrast to the direct effect model, which explains that it is a superior fit among theory and data (χ2/df = 2.44, RMSEA = 0.046, CFI = 0.956, GFI = 0.947, NFI = 0.948). Therefore, based on such results, hypothesis 4 is accepted, and it is confirmed that JE mediates between WFE and SCS.

Table 5.

Mediation results for H4.

5. Discussion and Implications

The present research was conducted to inquire about the impact of WFE on SCS from the perspective that JE mediates this relation. Hence, the findings of the current study confirmed that WFE positively improves SCS in the banking sector of Pakistan. The participants of this study validated that they are persuaded to achieve career satisfaction when they perceive their firms as supporting them to balance job and family roles by making employee-centered policies. Social exchange theory and the theory of role accumulation impressively explain this phenomenon. These theories might be used to explain how enrichment is linked to job-related and non-job-associated consequences. When workforces observe that firms are supporting them to assimilate work and family roles, they perceive their organizations as being more helpful and thus feel obliged to return with favorable inclinations to the company and job. In fact, employees desire more respect, reputation, good relationships, learning, and peace of mind. If the employee’s job is bringing family enrichment, its effects on job performance will be profound. The banks may bring work–family enrichment in multiple ways, for example, by avoiding unnecessary late sittings, more stressful environments, and undue pressures for meeting unrealistic targets. They might also allow the employees some paid vacations or events where they can participate with their families. These trivial events and gestures can bring more desire for a subjective career. Likewise, the more desire for a subjective career by the employees can stimulate the working environment towards a learning environment instead of just focusing too much on pay increments or promotion conflicts. This finding of the relationship between work–family enrichment and subjective career success is in line with Shah’s [40] views.

It is inferred by the results that if the job is bringing work–family enrichment it will positively bring more engagement to a certain extent. The possible explanation of having a strong and significant impact of work–family enrichment is peace of mind and personal satisfaction. When employees are satisfied in their personal lives, they can concentrate more on their work. The psychological anxiety or interruption of family life unpleasantly affects job engagement. Similarly, the researchers find support from the theory of work–family enrichment to elucidate these findings. According to work–family enrichment theory, when employees observe job and family resources influencing each other, they perceive that they are energetic, enthusiastic, and immersed in their work. Workers who feel as though their organizations urge them to both improve their work and home domains are more vigorously motivated to be involved in work-related tasks. The findings of the present survey are also consistent with the results of Hakanen and Peeters [103].

In the same way, the results of the current study also validated that job engagement affects subjective career success significantly. The authors are in line with the view of the conservation of resources theory. Nevertheless, subjective career success is only possible when the workers are psychologically and emotionally involved in their jobs. Psychological and emotional detachment cannot bring a sense of achievement and success. It is verified from the results that subjective career success is a product of job engagement. There are many motivational quotes that provide ample support that people derive better work experiences when they are enjoying their work and mentally and are emotionally engaged with their job. In the banking sector, which requires daily routine decisions and processes, the importance of job engagement is manifold. The human resource department needs to design a job in a way where, despite daily routines, employees feel more psychological and emotional experiences and attachment. Paid leaves, comfortable working environment, increments, and promotions are good tools in the banking sector, but the psychological and emotional associations with the employer, colleagues, and sense of autonomy can also bring cognitive and emotional attachment. More job engagement in the banking sector means more emphasis on the soft side of working experiences along with paid leaves, increments, and promotions.

These findings are harmonized with the previous literature of Bakker and Demerouti [104] and Joo and Ready [105] and are relevant to the relationship between work engagement and career success. However, in the banking sector, more focus is given on the quantitative side of career success, e.g., promotions, bonuses, and paid leave, whereas the qualitative side of career success, i.e., psychological and emotional gratification, views of society for life fulfillment, is focused on less.

This research augments in the pool of literature that work–family enrichment is a phenomenon that must be read in the industries where jobs are of more routine natures with long working hours. Likewise, the meaning of subjective career success where most of the reward system is focused around quantitative/monetary terms needs more empirical investigation regarding subjective career success.

It is evident that work–family enrichment brings job engagement in the banking sector, thus, HR departments need to focus more on devising such strategies that can bring a work–life enrichment into the lives of banking employees. More job engagement results in more commitment to the job, which is the desired outcome for every employer. Similarly, it is high time that the focus be given to the subjective side of career success in the banking sector. Most of the reward system in the banking sector is more focused around promotions and bonuses, but the subjective side of career success that is desired by most of the respondents in this research needs a different reward system.

The present study is also important for practitioners. First of all, this research offers a practical implication by emphasizing the significance of work–family enrichment for banking sector policymakers to achieve their objective to develop career satisfaction in workforces. In addition, this survey assists managers to improve awareness about the subjective career success of their subordinates. Practitioners should emphasize learning how employees of private banks recognize their careers. Managers should also design the jobs in a way to enhance the career satisfaction of employees. Moreover, another important practical inference of this research is that it highlights the role of work engagement to improve job fulfillment among bankers. Therefore, policymakers of the financial sector are recommended to endorse such job practices which promote the career gratification of employees. Banking sector specialists may arrange training for staff to avail job resources for their career success.

5.1. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this research offers theoretical as well as practical recommendations to private banks for improving their policies towards the well beings of employees, a few limitations need to be discussed. For instance, the scope of this study, the sample selection, and other factors could influence subjective career success. Nevertheless, these limitations also offer direction for upcoming investigations in this field. First, as a scope of the study, it only comprises private banks operating in Pakistan, and this might have restricted the applicability of outcomes. So, in order to extend outcomes, it can be beneficial to also duplicate this research in the public sector. Second, the sample size of the population can be increased to make the research more rigorous. This research is centered on the selection of individuals as a sample pool that can bound the generalization of results. Therefore, to infer broader generalizations, a larger sample is recommended. Similarly, the research merely mentioned private banks that were situated in a single city, and thus the geographical focus raises objections on the generalization of this study. Future scholars are appreciated by adding more cities such as Karachi, Faisalabad, and Rawalpindi to deal with such limitations. Another potential limitation of the current study is the inability of authors to stay in banks for longer duration due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers provided instructions to nominated bankers to manage this problem about how to fill the questionnaires and visited banks whenever they had any opportunity. However, respondents would feel insecure and lack of secrecy while providing their responses. A further limitation of the current research is that it employed cross-sectional data and predicts causation based on cross-sectional data that comprises certain risks. So, future investigations need to use longitudinal data. Moreover, in the literature, specific data on mediating role of job engagement between subjective career success and work–family enrichment is not available. Hence, future investigations could include a more in-depth study to comprehend the influence of factors on subjective career success. Moreover, potential researchers may find out the relationship between demographic factors (for example, married or unmarried employees, parents with children or single parents, etc.) and work–family enrichment. This might be helpful for the reader to make his understanding about results.

5.2. Conclusions

In conclusion, this research seeks to uncover the impact of work–family enrichment on subjective career success among bankers. Work engagement is also examined as a mediating variable between WFE and SCS in the banking sector of Pakistan, which is also a significant contribution to the literature of organization management. It is deduced that the work and family domains are interdependent on each other. Therefore, according to work–family enrichment theory, work may influence family life positively, and family characteristics can also affect work-related tasks. WFE affects work engagement positively such as when work and family roles take benefits from each other and employees feel more immersion in their jobs. Moreover, it can be inferred that workers seek not only monetary rewards in banking sector jobs but also desire inner satisfaction in their jobs in the form of subjective career success. In addition, WFE and work engagement are strong predictors of SCS. To summarize, this study discovered that top management might take advantage of the findings in the development of career satisfaction policies for the employees. The results of the present study bring attention from executives towards subjective career success of their workforces. This study also has a significant contribution to help practitioners understand the feelings of subordinates about their careers because banking jobs are more repetitive in nature. Furthermore, this survey points out that work engagement is a contributor to career satisfaction which can assist policymakers to design job descriptions of bankers to clarify their career path.

Author Contributions

K.A., N.A., R.T.N., M.S., M.A. and H.H. contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing and editing of the original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the respondents of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hauw, S.; Greenhaus, J. Building a Sustainable Career: The Role of Work–Home Balance in Career Decision Making. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; Volume 15, p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H. Employee Mobility in the Context of Sustainable Careers. In Employee Inter- and Intra-Firm Mobility; Cirillo, B., Tzabbar, D., Eds.; Advances in Strategic Management; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; Volume 41, pp. 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Nazaritehrani, A.; Mashali, B. Development of E-banking channels and market share in developing countries. Financ. Innov. 2020, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahman, Z.; Ali, A.; Jebran, K. The effects of mergers and acquisitions on stock price behavior in banking sector of Pakistan. J. Financ. Data Sci. 2018, 4, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YuSheng, K.; Ibrahim, M. Service innovation, service delivery and customer satisfaction and loyalty in the banking sector of Ghana. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1215–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Braganca, E.; Awang, Z.; Cyril De Run, E. You abuse but I will stay. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 899–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M.B.; Khapova, S.N.; Wilderom, C.P. Career success in a boundaryless career world. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Higgins, C.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Barrick, M.R. The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Pers. Psychol. 1999, 52, 621–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, A.E.; Spurk, D.; Volmer, J. The construct of career success: Measurement issues and an empirical example. Z. Für Arb. 2011, 43, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wayne, S.J.; Liden, R.C.; Kraimer, M.L.; Graf, I.K. The role of human capital, motivation and supervisor sponsorship in predicting career success. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, J.W.; Boswell, W.R.; Judge, T.A. Effects of personality on executive career success in the United States and Europe. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seibert, S.E.; Kraimer, M.L.; Liden, R.C. A social capital theory of career success. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 219–237. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L. Career construction theory and practice. Career Dev. Couns. Putt. Theory Res. Work 2013, 2, 144–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kraimer, M.L.; Greco, L.; Seibert, S.E.; Sargent, L.D. An investigation of academic career success: The new tempo of academic life. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2019, 18, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hirschi, A.; Dries, N. Antecedents and outcomes of objective versus subjective career success: Competing perspectives and future directions. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 35–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Cable, D.M.; Boudreau, J.W.; Bretz, R.D. An empirical investigation of the predictors of executive career success. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 485–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shockley, K.M.; Ureksoy, H.; Rodopman, O.B.; Poteat, L.F.; Dullaghan, T.R. Development of a new scale to measure subjective career success: A mixed-methods study. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 128–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.N.; Greenhaus, J.H.; Allen, T.D.; Johnson, R.E. Introduction to special topic forum: Advancing and expanding work-life theory from multiple perspectives. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, C.; Gatti, P.; Molino, M.; Cortese, C.G. Work–family conflict and enrichment in nurses: Between job demands, perceived organisational support and work–family backlash. J. Nurs. Manag. 2017, 25, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, L.M.; Li, Y.; Kwan, H.K.; Greenhaus, J.H.; DiRenzo, M.S.; Shao, P. A meta-analysis of the antecedents of work–family enrichment. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Greenhaus, J.H. How role jugglers maintain relationships at home and at work: A gender comparison. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasco-Saul, M.; Kim, W.; Kim, T. Leadership and employee engagement: Proposing research agendas through a review of literature. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Taris, T.W. Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 2008, 22, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work Engagement. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S. Work engagement: Current trends. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdamar, G.; Demirel, H. Investigation of work-family, family-work conflict of the teachers. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 4919–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wayne, J.H.; Butts, M.M.; Casper, W.J.; Allen, T.D. In search of balance: A conceptual and empirical integration of multiple meanings of work–family balance. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 70, 167–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; French, K.A.; Dumani, S.; Shockley, K.M. Meta-analysis of work–family conflict mean differences: Does national context matter? J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 90, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Thompson, M.J.; Andrews, M.C. Looking good and doing good: Family to work spillover through impression management. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNall, L.A.; Scott, L.D.; Nicklin, J.M. Do positive affectivity and boundary preferences matter for work–family enrichment? A study of human service workers. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.C. Work/Family Border Theory: A New Theory of Work/Family Balance. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulk, L.; Groeneveld, S. Work–life balance support in the public sector in Europe. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2012, 33, 384–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, J.; Yean Tan, F.; Tjik Zulkarnain, Z.I. Autonomy, workload, work-life balance and job performance among teachers. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.K.; Thomas, C.R.; Petts, R.J.; Hill, E.J. The Work-Family Interface. In Cross-Cultural Family Research and Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 323–354. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah; Zhou, D.; Shah, T.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, W.; Din, I.U.; Ilyas, A. Factors affecting household food security in rural northern hinterland of Pakistan. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, N.; Syed, G.K.; Mirani, D.A. Exploring the representation of gender and identity: Patriarchal and citizenship perspectives from the primary level Sindhi textbooks in Pakistan. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2018, 66, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Ferguson, M.; Hunter, E.M.; Clinch, C.R.; Arcury, T.A. Health and turnover of working mothers after childbirth via the work–family interface: An analysis across time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Zivnuska, S.; Ferguson, M.; Whitten, D. Work-family enrichment and job performance: A constructive replication of affective events theory. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S. The Role of Work-family Enrichment in Work-life Balance & Career Success: A Comparison of German & Indian Managers. Ph.D. Thesis, lmu, Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.; Kalliath, T.; Chan, X.W.; Kalliath, P. Enhancing job satisfaction through work–family enrichment and perceived supervisor support: The case of Australian social workers. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 2055–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beham, B.; Drobnič, S.; Präg, P.; Baierl, A.; Lewis, S. Work-to-family enrichment and gender inequalities in eight European countries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaga, A.; Bagraim, J. The relationship between work-family enrichment and work-family satisfaction outcomes. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2011, 41, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNall, L.A.; Nicklin, J.M.; Masuda, A.D. A meta-analytic review of the consequences associated with work–family enrichment. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.W.; Siu, O.L.; Cheung, F. A study of work–family enrichment among Chinese employees: The mediating role between work support and job satisfaction. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 63, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L. A Chinese longitudinal study on work/family enrichment. Career Dev. Int. 2011, 16, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.N.; Greenhaus, J.H. Is the opposite of positive negative? Untangling the complex relationship between work-family enrichment and conflict. Career Dev. Int. 2006, 11, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Justice in Social Exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, S.D. Toward a theory of role accumulation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1974, 39, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koekemoer, E.; Olckers, C. Women’s Wellbeing at Work: Their Experience of Work-Family Enrichment and Subjective Career Success. In Theory, Research and Dynamics of Career Wellbeing; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi, M.; Chaudhary, R. Job crafting and work-family enrichment: The role of positive intrinsic work engagement. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 651–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, G.; Zhou, E. Bidirectional work–family enrichment mediates the relationship between family-supportive supervisor behaviors and work engagement. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2017, 45, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.-K.; Lee, I. Workplace Happiness: Work Engagement, Career Satisfaction, and Subjective Well-Being. In Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017; Volume 5, pp. 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, B.E.; Lüthi, F. Job resources and career success of IVET graduates in Switzerland: A different approach to exploring the standing of VET. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2020, 72, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNall, L.A.; Bennett, M.; Nicklin, J. Work-Family Enrichment. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Maggino, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.; Oh, J.; Park, J.; Kim, W. The Relationship between Work Engagement and Work–Life Balance in Organizations: A Review of the Empirical Research. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2020, 19, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, M.K.; Stritch, J.M. Family-Friendly Policies, Gender, and Work–Life Balance in the Public Sector. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2017, 39, 422–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Richardson, J.; Boiarintseva, G. All of work? All of life? Reconceptualising work-life balance for the 21st century. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holland, P.; Tham, T.L.; Sheehan, C.; Cooper, B. The impact of perceived workload on nurse satisfaction with work-life balance and intention to leave the occupation. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2019, 49, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousin, O.; Collins, N.; Bartram, T.; Stanton, P. The relationship between work-life balance, the need for achievement, and intention to leave: Mixed-method study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 1478–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, A.A.; Breitenecker, R.J.; Shah, S.A.M. Relation of work-life balance, work-family conflict, and family-work conflict with the employee performance-moderating role of job satisfaction. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2018, 7, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S. Research on Work, Family, and Gender: Current Status and Future Directions. In Handbook of Gender and Work; Powell, G.N., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 391–412. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, J.H. Reducing Conceptual Confusion: Clarifying the Positive Side of Work and Family. In Handbook of Families and Work: Interdisciplinary Perspectives; University Press of America: Lanham, ML, USA, 2009; pp. 105–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, J.H.; Matthews, R.; Crawford, W.; Casper, W.J. Predictors and processes of satisfaction with work–family balance: Examining the role of personal, work, and family resources and conflict and enrichment. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 59, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Matthews, R.A.; Odle-Dusseau, H.; Casper, W.J. Fit of role involvement with values: Theoretical, conceptual, and psychometric development of work and family authenticity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R. Work-Family Balance. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J.C., Tetrick, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D.S.; Thompson, M.J.; Crawford, W.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Spillover and crossover of work resources: A test of the positive flow of resources through work–family enrichment. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, J.R.; Rothbard, N.P. Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beigi, M.; Wang, J.; Arthur, M.B. Work–family interface in the context of career success: A qualitative inquiry. Hum. Relat. 2017, 70, 1091–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Kossek, E.E. The contemporary career: A work–home perspective. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aryee, S.; Srinivas, E.S.; Tan, H.H. Rhythms of life: Antecedents and outcomes of work-family balance in employed parents. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, K.M.; Singla, N. Reconsidering work—family interactions and satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 861–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koekemoer, E.; Olckers, C.; Nel, C. Work–family enrichment, job satisfaction, and work engagement: The mediating role of subjective career success. Aust. J. Psychol. 2020, 72, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Smith, A.M. Work–Family Conflict and Health among Working Parents: Potential Linkages for Family Science and Social Neuroscience. Fam. Relat. 2016, 65, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siu, O.-L.; Lu, J.-F.; Brough, P.; Lu, C.-Q.; Bakker, A.B.; Kalliath, T.; O’Driscoll, M.; Phillips, D.R.; Chen, W.-Q.; Lo, D. Role resources and work–family enrichment: The role of work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Multiple levels in job demands-resources theory: Implications for employee well-being and performance. In Handbook of Well-Being; Diener, E., Oishi, S., Tay, L., Eds.; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Wright, T.A. When a" happy" worker is really a ”productive” worker: A review and further refinement of the happy-productive worker thesis. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2001, 53, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Cropanzano, R. (Eds.) From Thought to Action Employee Work Engagement and Job Performance; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-H.; Chen, H.-T. Relationships among workplace incivility, work engagement and job performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 3, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Leiter, M.P. (Eds.) Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lizano, E.L. Work Engagement and Its Relationship with Personal Well-Being: A Cross-Sectional Exploratory Study of Human Service Workers. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.B.; McKechnie, S.; Swanberg, J. Predicting employee engagement in an age-diverse retail workforce. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.; Eissenstat, S.J. An application of work engagement in the job demands–resources model to career development: Assessing gender differences. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2018, 29, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Wayne, J.H.; Grzywacz, J.G. Measuring the positive side of the work–family interface: Development and validation of a work–family enrichment scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S.; Wormley, W.M. Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 64–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire a cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Arshad, M.Z.; waqas Kamran, H.; Scholz, M.; Han, H. Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility at the Micro-Level and Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior and the Moderating Role of Gender. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Han, H.; Scholz, M. Corporate social responsibility at the micro-level as a “new organizational value” for sustainability: Are females more aligned towards it? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Rabbani, M.R.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cheng, G.; Zia-Ud-Din, M.; Fu, Q. CSR, Co-Creation and Green Consumer Loyalty: Are Green Banking Initiatives Important? A Moderated Mediation Approach from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Saeed, A.; Iqbal, M.K.; Saeed, U.; Sadiq, I.; Faraz, N.A. Linking corporate social responsibility to customer loyalty through co-creation and customer company identification: Exploring sequential mediation mechanism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar, J.J. Applications of structural equation modelling with AMOS 21, IBM SPSS. In Structural Equation Modelling; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 35–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, J.-H.; Memon, M.A.; Richard, J.E.; Ting, H.; Cham, T.-H. CB-SEM latent interaction: Unconstrained and orthogonalized approaches. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, W.; Tripopsakul, S. The Impact of Digital Social Responsibility on Preference and Purchase Intentions: The Implication for Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Assessing Mediation in Communication Research. In The Sage Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication; Sage Publications: Shozen Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hakanen, J.; Peeters, M. How do work engagement, workaholism, and the work-to-family interface affect each other? A 7-year follow-up study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joo, B.-K.; Ready, K.J. Career satisfaction. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).