The Moderator Role of Financial Well-Being on the Effect of Job Insecurity and the COVID-19 Anxiety on Burnout: A Research on Hotel-Sector Employees in Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Relationship between COVID-19 Anxiety and Burnout Syndrome

2.2. Relationship between Job Insecurity and Burnout Syndrome

2.3. The Moderating Role of Financial Well-Being

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample Procedure

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Data Analyses

4. Findings

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

4.3. CMV Evaluation

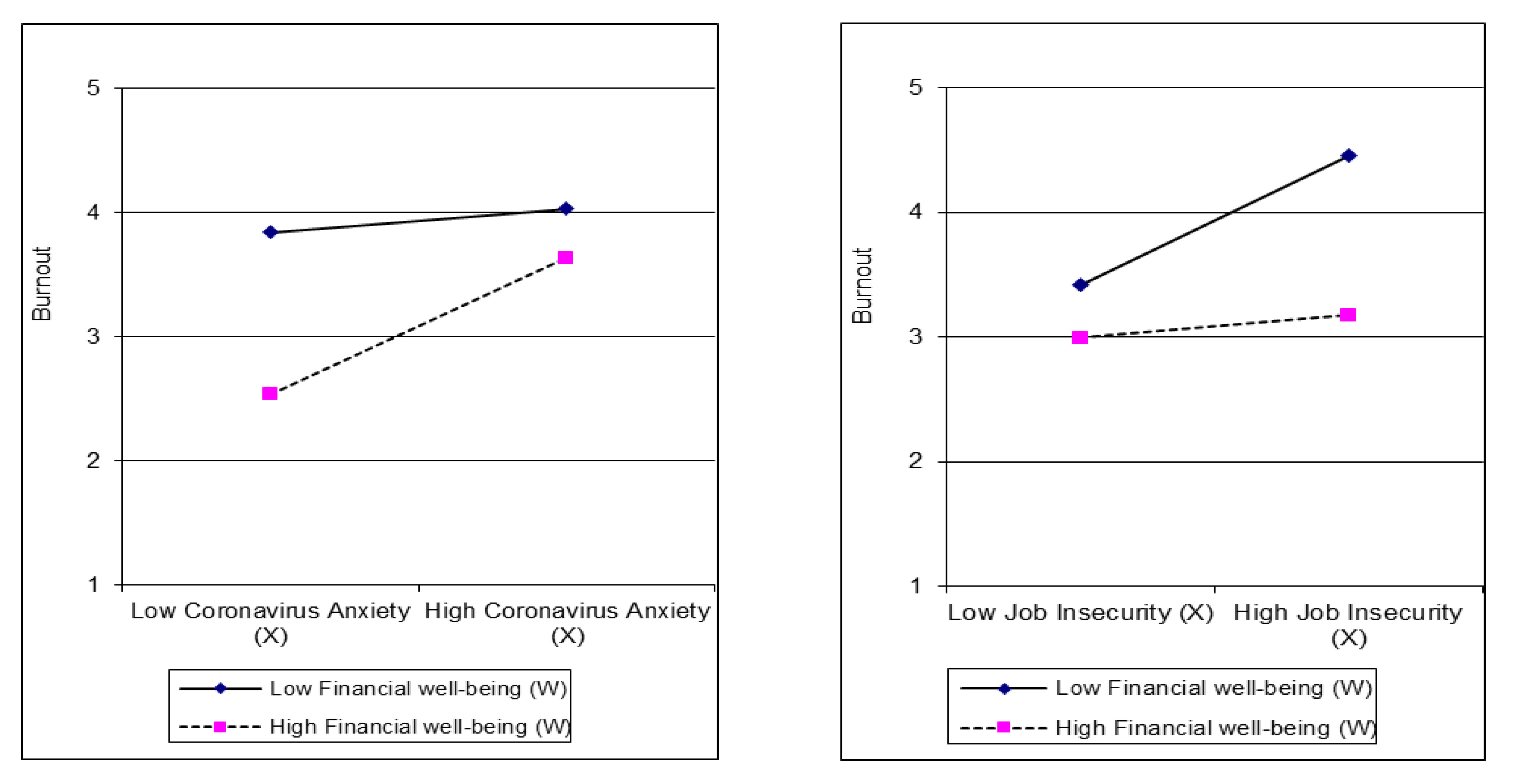

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

Theoretical and Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jung, H.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Yoon, H.H. COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, R.; McKercher, B. The impact of SARS on Hong Kong’s tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 16, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J. The Effect of the SARS Illness on Tourism in Taiwan: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Manag. 2005, 22, 497–506. [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo, G.; Dube, K.; Chikodzi, D. Impacts and Implications of COVID-19 on the Global Hotel Industry and Airbnb. In Counting the Cost of COVID-19 on the Global Tourism Industry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Lyu, J.; Latif, A.; Lorenzo, A. COVID-19 and sectoral employment trends: Assessing resilience in the US leisure and hospitality industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, D.; Melnik, O. Hurricane Katrina’s Effect on The Perception of New Orleans Leisure Tourists. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Modes of Transmission of Virus Causing COVID-19: Implications for IPC Precaution Recommendations. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331601/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Transmission_modes-2020.1-eng.pdf. (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Teng, Y.-M.; Wu, K.-S.; Lin, K.-L.; Xu, D. Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Quarantine Hotel Employees in China. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 2743–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Park, J.; Hyun, S.S. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on employees’ work stress, well-being, mental health, organizational citizenship behavior, and employee-customer identification. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo-Thanh, T.; Vu, T.-V.; Nguyen, N.P.; Van Nguyen, D.; Zaman, M.; Chi, H. COVID-19, frontline hotel employees’ perceived job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: Does trade union support matter? J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, I.; Khalid, T.J.; Qabajah, M.R.; Barnard, A.G.; Qushmaq, I.A. Healthcare Workers Emotions, Perceived Stressors and Coping Strategies During a MERS-CoV Outbreak. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 14, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baum, T.; Mooney, S.K.; Robinson, R.N.; Solnet, D. COVID-19′s impact on the hospitality workforce—New crisis or amplification of the norm? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2813–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, T.; Coulombe, S.; Khalil, C.; Meunier, S.; Doucerain, M.; Auger, É.; Cox, E. Job security and the promotion of workers’ wellbeing in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic: A study with Canadian workers one to two weeks after the initiation of social distancing measures. Int. J. Wellbeing 2020, 10, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.I.; Niazi, A.; Nasir, A.; Hussain, M.; Khan, M.I. The Effect of COVID-19 on the Hospitality Industry: The Implication for Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Wang, Y.; Rauch, A.; Wei, F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 288, 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouche, S. COVID-19 and employees’ mental health: Stressors, moderators and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Res. 2020, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vo-Thanh, T.; Vu, T.-V.; Nguyen, N.P.; Van Nguyen, D.; Zaman, M.; Chi, H. How does hotel employees’ satisfaction with the organization’s COVID-19 responses affect job insecurity and job performance? J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 907–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Dunn, R.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J.; Greenberg, N. A Systematic, Thematic Review of Social and Occupational Factors Associated With Psychological Outcomes in Healthcare Employees During an Infectious Disease Outbreak. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stergiou, D.P.; Farmaki, A. Ability and willingness to work during COVID-19 pandemic:Perspectives of front-line hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources Theory: Its Implication for Stress, Health, and Resilience. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A. The Job Demands–Resources model: Challenges for future research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasdi, R.M.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ahrari, S. Financial Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Spillover Effects on Burnout–Disengagement Relationships and Performance of Employees Who Moonlight. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 610138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathi, N.; Lee, K. Emotional exhaustion and work attitudes: Moderating effect of personality among frontline hospitality employees. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 15, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachem, R.; Tsur, N.; Levin, Y.; Abu-Raiya, H.; Maercker, A. Negative Affect, Fatalism, and Perceived Institutional Betrayal in Times of the Coronavirus Pandemic: A Cross-Cultural Investigation of Control Beliefs. Front. Psychiatr. 2020, 11, 589914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafini, G.; Parmigiani, B.; Amerio, A.; Aguglia, A.; Sher, L.; Amore, M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. Qjm Int. J. Med. 2020, 113, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. The Psychology of Pandemics: Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak of Infectious Disease; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Somani, A. Dealing with Corona virus anxiety and OCD. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 51, 102053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xiang, Y.-T.; Liu, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, B. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020, 7, e17–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.; Hou, W.K.; Sun, S.; Ben-Ezra, M. Psychological and Behavioural Responses to COVID-19: A China–Britain Comparison. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakose, T.; Malkoc, N. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical doctors in Turkey. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2021, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.A.; Sakib, N.; Gozal, D.; Bhuiyan, A.I.; Hossain, S.; Doza, B.; Al Mamun, F.; Hosen, I.; Safiq, M.B.; Abdullah, A.H.; et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and serious psychological consequences in Bangladesh: A population-based nationwide study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.M.; Ashtari, S.; Fetrat, M.K. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health of Iranian Population. Int. J. Travel Med. Glob. Health 2020, 9, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafim, A.P.; Durães, R.S.S.; Rocca, C.C.A.; Gonçalves, P.D.; Saffi, F.; Cappellozza, A.; Paulino, M.; Dumas-Diniz, R.; Brissos, S.; Brites, R.; et al. Exploratory study on the psychological impact of COVID-19 on the general Brazilian population. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, S.; Sunil, R.; Bhatt, M.T.; Bhumika, T.V.; Thomas, N.; Puranik, A.; Shwethapriya, R. Weathering the Storm: Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Clinical and Nonclinical Healthcare Workers in India. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Anxiety Disorders. In DSM-V. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; New School Library: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: http://repository.poltekkes-kaltim.ac.id/657/1/Diagnostic%20and%20statistical%20manual%20of%20mental%20disorders%20_%20DSM-5%20%28%20PDFDrive.com%20%29.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Kader Maideen, S.F.; Mohd Sidik, S.; Rampal, L.; Mukhtar, F. Prevalence, associated factors and predictors of anxiety: A community survey in Selangor, Malaysia. BMC Psychiatr. 2015, 15, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yetgin, D.; Benligiray, S. The effect of economic anxiety and occupational burnout levels of tour guides on their occupational commitment. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.W.; Piao, Z.; Ko, J.Y. Descriptive or injunctive: How do restaurant customers react to the guidelines of COVID-19 prevention measures? The role of psychological reactance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnipseed, D.L. Anxiety and Burnout in the Health Care Work Environment. Psychol. Rep. 1998, 82, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchand, G.; Russell, K.C.; Cross, R. An Empirical Examination of Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Field Instructor Job-Related Stress and Retention. J. Exp. Educ. 2009, 31, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcıoğlu, I.; Kızanıklı, M.M. The Effects of Trait Anxiety on the Intention of Leaving and Burnout of Restaurant Employees. Tour. Acad. J. 2019, 5, 238–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tarcan, G.Y.; Tarcan, M.; Top, M. An analysis of relationship between burnout and job satisfaction among emergency health professionals. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2016, 28, 1339–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumayr-Pintar, C.; Cerf, C.; Parent-Thirion, A. Burnout in the Workplace: A Review of Data and Policy Responses in the EU; Research report/Eurofound; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.J. A Phenomenological Analysis of Anxiety as Experienced in Social Situations. J. Phenomenol. Psychol. 2013, 44, 179–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Eyoun, K. Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakut, E.; Kuru, Ö.; Güngör, Y. Determination of the Influence of Work Overload and Perceived Social Support in the Effect of the Covid-19 Fears of Healthcare Personnel on Their Burnout by Structural Equation Modelling. EKEV Akad. Derg. 2020, 24, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Solmaz, F. COVID-19 burnout, COVID-19 stress and resilience: Initial psychometric properties of COVID-19 Burnout Scale. Death Stud. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakioğlu, F.; Korkmaz, O.; Ercan, H. Fear of COVID-19 and Positivity: Mediating Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, B.; Gocet-Tekin, E.; Deniz, M.E.; Satici, S.A. Adaptation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Its Association with Psychological Distress and Life Satisfaction in Turkey. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, L.; Rosenblatt, Z. Job Insecurity: Toward Conceptual Clarity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pienaar, J.; Witte, H.D.; Hellgren, J.; Sverke, M. The Cognitive/Affective Distinction of Job Insecurity: Validation and Differential Relations. S. Afr. Bus. Rev. 2013, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sverke, M.; Hellgren, J.; Näswall, K. No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoghbi-Manrique-De-Lara, P.; Ting-Ding, J.-M.; Guerra-Báez, R. Indispensable, Expendable, or Irrelevant? Effects of Job Insecurity on the Employee Reactions to Perceived Outsourcing in the Hotel Industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 58, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, D. The Moderating Effect of Self-efficacy on Job Insecurity and Organisational Commitment among Nigerian Public Servants. J. Psychol. Afr. 2006, 16, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.; Jiang, L.; Graso, M. Leader–member exchange: Moderating the health and safety outcomes of job insecurity. J. Saf. Res. 2016, 56, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauno, S.; Cheng, T.; Lim, V. The Far-Reaching Consequences of Job Insecurity: A Review on Family-Related Outcomes. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2017, 53, 717–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Stefano, G.; Venza, G.; Aiello, D. Associations of Job Insecurity with Perceived Work-Related Symptoms, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Leader–Member Exchange and the Moderating Role of Organizational Support. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgard, S.A.; Brand, J.E.; House, J.S. Perceived job insecurity and worker health in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ciccarelli, A.; Fabrizi, E.; Romano, E.; Zoppoli, P. Health, Well-Being and Work History Patterns: Insight on Territorial Differences. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Nyberg, S.T.; Batty, G.; Jokela, M.; Heikkila, K.; Fransson, E.; Alfredsson, L.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; et al. Perceived job insecurity as a risk factor for incident coronary heart disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2013, 347, f4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrie, J.E.; Shipley, M.J.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Marmot, M. Effects of chronic job insecurity and change in job security on self reported health, minor psychiatric morbidity, physiological measures, and health related behaviours in British civil servants: The Whitehall II study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.-M. When do job-insecure employees keep performing well? The buffering roles of help and prosocial motivation in the relationship between job insecurity, work engagement, and job performance. J. Bus. Psychol. 2021, 36, 659–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Probst, T.M. The rich get richer and the poor get poorer: Country- and state-level income inequality moderates the job insecurity-burnout relationship. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M. The Impact of Job Insecurity on Employee Work Attitudes, Job Adaptation and Organizational Withdrawal Behaviours. In The Psychology of Work: Theoretically Based Empirical Research; Brett, J.M., Drasgow, F., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Rothmann, S.; Jackson, L.T.B.; Kruger, M.M. Burnout and job stress in a local government: The moderating effect of sense of coherence. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2003, 29, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Çetin, Y.D.D.C. The Relationship between Job Insecurı-Ity and Burnout -Sample of Municipal Polices. Celal Bayar Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 13, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitmiş, M.G.; Ergeneli, A. How Psychological Capital Influences Burnout: The Mediating Role of Job Insecurity. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oprea, B.; Iliescu, D. Burnout and Job Insecurity: The Mediating Role of Job Crafting. Psihol. Resur. Umane 2015, 13, 232–244. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J.; Haar, J.; Harris, C. Job Insecurity and Job Burnout: Does Union Membership Buffer the Detrimental Effects? N. Z. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 17, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Katlav, E.Ö.; Çetin, B.; Perçin, N.Ş. The Effect of Tourist Guides’ Perceptions of Job Insecurity on Burnout. J. Travel Hosp. Manag. 2020, 18, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.P. The Under 40 Financial Planning Guide: From Graduation to Your First House; Silver Lake Publishing: Aberdeen, WA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, S. Personal Financial Wellness. In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research; Xiao, J.J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Halleröd, B.; Seldén, D. The Multi-dimensional Characteristics of Wellbeing: How Different Aspects of Wellbeing Interact and Do Not Interact with Each Other. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggen, E.C.; Hogreve, J.; Holmlund, M.; Kabadayi, S.; Löfgren, M. Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panisch, L.S.; Prost, S.G.; Smith, T.E. Financial well-being and physical health related quality of life among persons incarcerated in jail. J. Crime Justice 2019, 42, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CFPB (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau). Financial Well-Being: The Goal of Financial Education. 2015. Available online: https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_report_financial-well-being.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Prendergast, S.; Blackmore, D.; Kempson, E.; Kutin, J. Financial Well-Being: A Survey of Adults in Australia. ANZ Banking Group Limited. 2018. Available online: https://www.financialcapability.gov.au/files/anz-financial-wellbeing-summary-report-australia.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Swift, S.L.; Bailey, Z.; Al Hazzouri, A.Z. Improving the Epidemiological Understanding of the Dynamic Relationship Between Life Course Financial Well-Being and Health. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2019, 6, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 35, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prenovitz, S. What happens when you wait? Effects of Social Security Disability Insurance wait time on health and financial well-being. Health Econ. 2021, 30, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, S.; Fenn, K.; Meadows, R. Subjective financial well-being, income and health inequalities in mid and later life in Britain. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 100, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Garman, E.; Sorhaindo, B. Relationships Among Credit Counseling Clients’ Financial Well-Being, Financial Behaviors, Financial Stressor Events, and Health. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2003, 14, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, B.; Sorhaindo, B.; Xiao, J.J.; Garman, E.T. Negative Health Effects of Financial Stress. Consum. Interes. Annu. 2005, 51, 260–262. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, B.; Xiao, J.J.; Sorhaindo, B.; Garman, E. Financially Distressed Consumers: Their Financial Practices, Financial Well-Being, and Health. Hum. Dev. Fam. Sci. Fac. Publ. 2005, 16, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Campara, J.P.; Vieira, K.M.; Potrich, A.C.G. Satisfação Global de Vida e Bemestar Financeiro: Desvendando a percepção de beneficiários do Programa Bolsa Família. Braz. J. Public Adm. 2017, 51, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verduzco-Gutierrez, M.; Larson, A.R.; Capizzi, A.N.; Bean, A.C.; Do, R.D.Z.; Odonkor, C.A.; Bosques, G.; Silver, J.K. How Physician Compensation and Education Debt Affects Financial Stress and Burnout: A Survey Study of Women in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. PM&R 2021, 13, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar, G.İ.; Akduman, G.; Hatïpoğlu, Z. The Relationship of Financial Wellbeing to Burnout According to Generations. Istanb. Manag. J. 2018, 29, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sabri, M.F.; Aw, E.C.-X. Untangling financial stress and workplace productivity: A serial mediation model. J. Work. Behav. Health 2020, 35, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Tourism Statistics (January–September 2020). Available online: https://yigm.ktb.gov.tr/Eklenti/81888,30032020yilliksinirbulteni-xlsx-1xlsx.xlsx?0. (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Soper, D.S. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software]. 2021. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Lee, S.A. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evren, C.; Evren, B.; Dalbudak, E.; Topcu, M.; Kutlu, N. Measuring anxiety related to COVID-19: A Turkish validation study of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale. Death Stud. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-González, S.; Fernández-López, S.; Rey-Ares, L.; Rodeiro-Pazos, D. The Influence of Attitude to Money on Individuals’ Financial Well-Being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 148, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malach-Pines, A. The Burnout Measure, Short Version. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravetter, F.; Wallnau, L. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 8th ed.; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuller, C.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-J.; Van Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. From the Editors: Common method variance in international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Kim, S.; Zhang, S.X.; Foo, M.-D.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Yáñez, J.A. Hospitality workers’ COVID-19 risk perception and depression: A contingent model based on transactional theory of stress model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Ali, F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, P.M. Public health and the world economic crisis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.-S.; Gunnell, D.; Sterne, J.A.; Lu, T.-H.; Cheng, A.T. Was the economic crisis 1997–1998 responsible for rising suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia? A time–trend analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, M.; Gili, M.; Garcia-Campayo, J.; García-Toro, M. Economic crisis and mental health in Spain. Lancet 2013, 382, 1977–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.C.-C.; Cheung, F.; Wu, A.M. Job Insecurity, Occupational Future Time Perspective, and Psychological Distress Among Casino Employees. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019, 35, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Biswas-Diener, R. Will Money Increase Subjective Well-Being? Soc. Indic. Res. 2002, 57, 119–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci, N.; Giorgi, G.; Roncaioli, M.; Perez, J.F.; Arcangeli, G. The correlation between stress and economic crisis: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Houdmont, J.; Kerr, R.; Addley, K. Psychosocial factors and economic recession: The Stormont Study. Occup. Med. 2012, 62, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giorgi, G.; Shoss, M.; Leon-Perez, J.M. Going beyond workplace stressors: Economic crisis and perceived employability in relation to psychological distress and job dissatisfaction. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2015, 22, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimoff, J.K.; Kelloway, E.K. Mental Health Problems are Management Problems: Exploring the Critical Role of Managers in Supporting Employee Mental Health. Organ. Dyn. 2018, 48, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Yavas, U.; Babakus, E.; Deitz, G.D. The effects of organizational and personal resources on stress, engagement, and job outcomes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-M.; Mohammad, A.A.; Kim, W.G. Understanding hotel frontline employees’ emotional intelligence, emotional labor, job stress, coping strategies and burnout. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.; Yu, J.; Chua, B.-L.; Lee, S.; Han, H. Relationships among Emotional and Material Rewards, Job Satisfaction, Burnout, Affective Commitment, Job Performance, and Turnover Intention in the Hotel Industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 371–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.K.; Probst, T.M. Multilevel Outcomes of Economic Stress: An Agenda for Future Research. In The Role of the Economic Crisis on Occupational Stress and Well Being; Perrewé, P.L., Halbesleben, J.R.B., Rosen, C.C., Eds.; Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2012; Volume 10, pp. 43–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W. Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands—Resources model. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 12, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bohle, P.; Quinlan, M. Managing Occupational Health and Safety: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 2nd ed.; Macmillan: Melbourne, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Üngüren, E.; Koç, T.S. Konaklama İşletmelerinde İş Sağlığı ve Güvenliği Uygulamalarının Örgütsel Güven Üzerindeki Etkisi. ISGUC J. Ind. Relat. Hum. Resour. 2016, 18, 123–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.-Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bareket-Bojmel, L.; Shahar, G.; Margalit, M. COVID-19-Related Economic Anxiety Is As High as Health Anxiety: Findings from the USA, the UK, and Israel. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; de Los Santos, J.A.A. Fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Bakker, A. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watterson, A. COVID-19 in the UK and Occupational Health and Safety: Predictable not Inevitable Failures by Government, and Trade Union and Nongovernmental Organization Responses. EW Solut. J. Environ. Occup. Health Policy 2020, 30, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factors | Mean | SD | Estimate | S.E. | t Value | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Anxiety | 1.49 | 1.04 | |||||

| I felt dizzy, lightheaded, or faint, when I read or listened to news about the coronavirus | 1.37 | 1.24 | 0.883 | Fixed | −0.058 | −0.251 | |

| I had trouble falling or staying asleep because I was thinking about the coronavirus. | 1.66 | 1.27 | 0.830 | 0.043 | 22.007 *** | −0.157 | −0.894 |

| I felt paralyzed or frozen when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus. | 1.61 | 1.15 | 0.806 | 0.044 | 20.561 *** | −0.023 | −0.335 |

| I lost interest in eating when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus | 1.51 | 1.17 | 0.837 | 0.048 | 21.946 *** | −0.059 | −0.447 |

| I felt nauseous or had stomach problems when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus. | 1.35 | 1.16 | 0.850 | 0.046 | 22.535 *** | −0.084 | −0.580 |

| Perceived Job Insecurity | 3.44 | 0.96 | |||||

| I worry about the continuation of my career | 3.30 | 1.12 | 0.920 | Fixed | 0.109 | −0.518 | |

| I am certain/sure of my job environment | 3.43 | 1.11 | 0.895 | 0.032 | 29.602 *** | 0.004 | −0.694 |

| I am very sure that I will be able to keep my job | 3.46 | 1.16 | 0.881 | 0.035 | 28.113 *** | 0.050 | −0.143 |

| I think that I will be able to continue working here | 3.49 | 1.08 | 0.870 | 0.037 | 27.106 | 0.087 | −0.375 |

| I fear that I might get fired | 3.47 | 1.13 | 0.793 | 0.039 | 22.025 *** | 0.381 | −0.485 |

| I fear that I might lose my job | 3.45 | 1.10 | 0.809 | 0.041 | 22.838 *** | 0.046 | −0.984 |

| There is only a small chance that I will become unemployed | 3.45 | 1.06 | 0.775 | 0.041 | 21.025 *** | 0.121 | −0.669 |

| I feel uncertain about the future of my job | 3.47 | 1.08 | 0.848 | 0.038 | 25.363 *** | 0.090 | −0.751 |

| Financial Well-Being | 2.76 | 0.99 | |||||

| I tend to worry about paying my normal living expenses | 2.65 | 1.11 | 0.924 | Fixed | −0.016 | −0.899 | |

| I have too much debt right now | 2.84 | 1.08 | 0.844 | 0.040 | 23.430 *** | −0.315 | −0.614 |

| I pay my bills on time | 2.81 | 1.05 | 0.880 | 0.039 | 25.751 *** | −0.310 | −0.708 |

| Burnout (When I think about COVID-19 overall) | 3.52 | 0.74 | |||||

| I often feel tired | 3.40 | 0.90 | 0.872 | Fixed | −0.205 | −0.769 | |

| I often feel disappointed with people | 3.70 | 0.98 | 0.873 | 0.045 | 24.300 *** | −0.161 | −1.00 |

| I often feel hopeless | 3.51 | 0.89 | 0.819 | 0.047 | 21.378 *** | −0.145 | −0.941 |

| I often feel trapped. | 3.57 | 0.93 | 0.818 | 0.049 | 21.284 *** | −0.071 | −0.911 |

| I often feel helpless | 3.53 | 0.92 | 0.776 | 0.049 | 19.556 *** | 0.041 | −1.16 |

| I often feel depressed | 3.58 | 0.89 | 0.792 | 0.050 | 20.202 *** | 0.434 | −1.05 |

| I feel physically weak/sickly | 3.53 | 0.93 | 0.727 | 0.053 | 17.581 *** | 0.387 | −0.920 |

| I often feel worthless/like a failure | 3.44 | 0.89 | 0.771 | 0.049 | 19.265 *** | 0.229 | −0.874 |

| I often feel difficulties sleeping | 3.46 | 0.90 | 0.716 | 0.057 | 17.172 *** | 0.277 | −0.924 |

| I often feel “I’ve had it” | 3.46 | 0.83 | 0.802 | 0.048 | 20.614 *** | 0.173 | −1.28 |

| Model | X2 | df | X2/df | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA | Model Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆X2 | ∆df | p (∆X2) | ||||||||

| Four factors a | 434.93 | 293 | 1.48 | 0.984 | 0.031 | 0.035 | - | - | ||

| Three factors b | 1191.49 | 296 | 4.02 | 0.896 | 0.080 | 0.088 | 2 vs. 1 | 756.56 | 3 | 0.000 |

| Two factors c | 2591.48 | 298 | 8.69 | 0.735 | 0.152 | 0.140 | 3 vs. 1 | 215.55 | 5 | 0.000 |

| One factor d | 4107.09 | 299 | 13.73 | 0.560 | 0.152 | 0.180 | 4 vs. 1 | 3672.16 | 6 | 0.000 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | α | AVE | CR | MSV | ASV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) COVANX | (0.841) a | 0.923 | 0.708 | 0.924 | 0.195 | 0.087 | |||

| (2) PERJINS | 0.250 ** | (0.850) a | 0.954 | 0.723 | 0.954 | 0.353 | 0.220 | ||

| (3) BURNOUT | 0.442 ** | 0.594 ** | (0.798) a | 0.945 | 0.637 | 0.946 | 0.353 | 0.288 | |

| (4) FINWLBNG | 0.041 | −0.496 ** | −0.561 ** | (0.883) a | 0.913 | 0.780 | 0.809 | 0.315 | 0.187 |

| Variable | β | SE | t | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.51 | 0.026 | 133.615 *** | Supported |

| H1: COVANX → BURNOUT | 0.32 | 0.025 | 9.604 *** | Supported |

| H2: PERJINS → BURNOUT | 0.30 | 0.028 | 8.012 *** | Supported |

| H3: FINWELL → BURNOUT | −0.42 | 0.028 | −11.142 *** | Supported |

| H3a: COVANX × FINWELL → BURNOUT | 0.25 | 0.024 | 7.138 *** | Supported |

| H3b: PERJINS × FINWELL → BURNOUT | −0.20 | 0.027 | −5.911 *** | Supported |

| R2 = 0.545; *** p < 0.001 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Üngüren, E.; Tekin, Ö.A.; Avsallı, H.; Kaçmaz, Y.Y. The Moderator Role of Financial Well-Being on the Effect of Job Insecurity and the COVID-19 Anxiety on Burnout: A Research on Hotel-Sector Employees in Crisis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169031

Üngüren E, Tekin ÖA, Avsallı H, Kaçmaz YY. The Moderator Role of Financial Well-Being on the Effect of Job Insecurity and the COVID-19 Anxiety on Burnout: A Research on Hotel-Sector Employees in Crisis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):9031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169031

Chicago/Turabian StyleÜngüren, Engin, Ömer Akgün Tekin, Hüseyin Avsallı, and Yaşar Yiğit Kaçmaz. 2021. "The Moderator Role of Financial Well-Being on the Effect of Job Insecurity and the COVID-19 Anxiety on Burnout: A Research on Hotel-Sector Employees in Crisis" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 9031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169031

APA StyleÜngüren, E., Tekin, Ö. A., Avsallı, H., & Kaçmaz, Y. Y. (2021). The Moderator Role of Financial Well-Being on the Effect of Job Insecurity and the COVID-19 Anxiety on Burnout: A Research on Hotel-Sector Employees in Crisis. Sustainability, 13(16), 9031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169031