Planning for Urban Social Sustainability: Towards a Human-Centred Operational Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

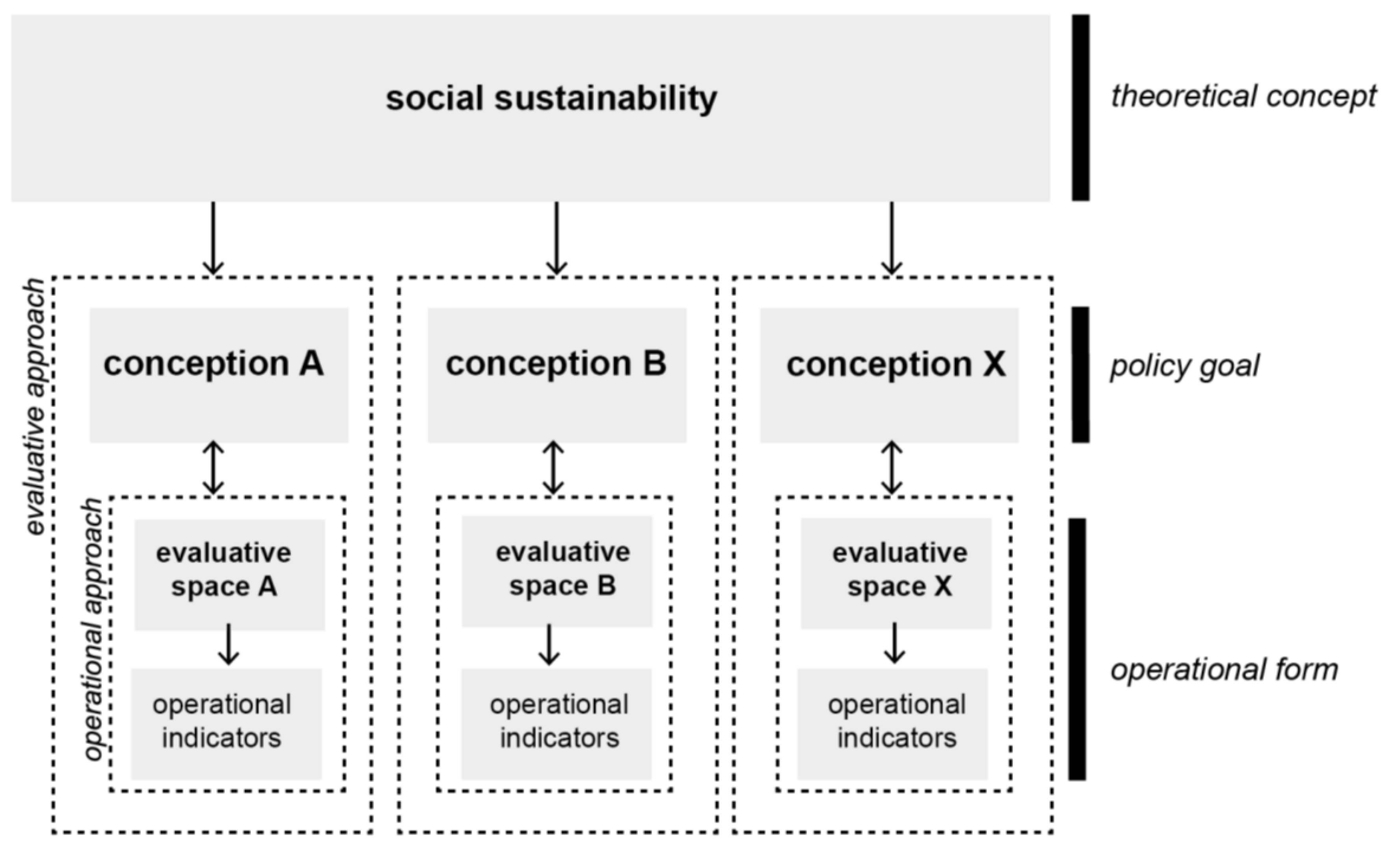

2. Steps of Operationalisation: From a Value-Laden Plurality to Concrete Indicators

3. A Capability Conception to Social Sustainability

4. Operationalising Social Sustainability in Dutch Urban Planning Practice

4.1. Emprical Exploration

4.2. Three Dimensions of Policy Operationalisation in The Netherlands

5. Discussion: Complementarity between Resources and Capabilities

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dixon and Woodcraft [31] | Dempsey et al. [15] | Shirazi and Keivani [29] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible | |||

| decent housing | - | decent housing mixed tenure | quality of home building typology social mix |

| transport | transport links | accessibility (e.g., to local services and facilities/employment/green space) | |

| daily facilities | - | - | access to facilities |

| recreation | provision for teenagers and young people shared spaces that enable neighbours to meet space that can be used by local groups | walkable neighbourhood; pedestrian friendly | quality of centre |

| jobs | - | employment | - |

| schools | schools | education and training | - |

| public spaces | public space playgrounds | attractive public realm | - |

| healthcare | services for older people healthcare | - | - |

| urban design | - | urbanity local environmental quality and amenity sustainable urban design neighbourhood | quality of neighbourhood density mixed land use urban pattern and connectivity |

| Intangible | |||

| social interaction | how people living in different parts of a neighbourhood relate to each other how well people from different backgrounds co-exist | social interaction social justice social order social cohesion | social networking and interaction |

| social networks | relationships between neighbours and local social networks | social capital social inclusion (and eradication of social exclusion) social networks | social networking and interaction |

| cultural expression | - | cultural traditions | - |

| feeling of belonging | how people feel about their neighbourhood sense of belonging and local identity | sense of community and belonging | sense of attachment |

| feeling of community | - | community cohesion (i.e., cohesion between and among different groups) | - |

| safety | feelings of safety | safety residential stability (vs turnover) | safety and security |

| well-being | quality of life and well-being | health, quality of life and well-being | - |

| existence of informal groups and associations | the existence of informal groups and associations that allow people to make their views known | active community organizations | - |

| representation by local governments | local governance structures responsiveness of local government to local issues | local democracy | - |

| levels of participation | - | participation | participation |

| levels of influence | residents’ perceptions of their influence over the wider area and whether they will get involved to tackle wider problems. | - | - |

| Social Sustainability | Leefbaarometer |

|---|---|

| Tangible | |

| decent housing | housing part before 1900 housing part between 1900–1920 housing part between 1920–1945 housing part between 1945–1960 housing part between 1961–1971 housing part between 1971–1980 housing part between 1991–2000 historical housing dominance of pre-war dominance of early post-war dominance of late post-war dominance of recent buildings part of single household row-housing large freestanding and duo-housing medium-size freestanding and duo-housing small freestanding and duo-housing dominance pre-war single household part of small single household before 1900 part of small pre-war single household housing part of small single household housing 1900–1945 part of small single household housing 1970–1990 part of small multiple household housing after 1970 part of single household social rent part of single household for sale part of multiple household for sale |

| transport | distance to train station distance to transfer station distance to driveway highway |

| daily facilities | number of shops for daily groceries within 1 km distance to closest atm day recreation facilities disappeared supermarket |

| recreation | number of cafes within 1 km cafes and cafeterias (combined index) number of restaurants within 1 km catering industry and shops (combined index) smaller shops library within 2 km number of stages within 10 km distance to closest swimming pool proximity to forest part of green proximity to parks proximity to IJsselmeer/Markermeer proximity to recreative water proximity to North Sea coast proximity to North Sea |

| jobs | - |

| schools | number of primary schools within 1 km education and healthcare (combined index) |

| public spaces | - |

| healthcare | number of general practitioners within 3 km distance to closest hospital |

| urban design | urban facilities part of national monuments part of buildings with industrial function part of buildings with public function density proximity to residential area proximity to ‘open, dry, natural area’ water in neighbourhood high voltage pylonsnoise pollution distance to main road network distance to high way number of trains proximity to rail track proximity to roads proximity to chloride area industry nearby flood risk earthquake risk |

| - | mutation rate |

| - | part of wester migrants part of ‘moe-landers’ part of non-western migrants part of Moroccans part of Surinamese part of Turks part of other non-western migrants single parent families families with children families without children part of incapacitated part of welfare recipients elderly development of households development of 15–24 year old’s |

| Intangible | |

| social interaction | socio-cultural facilities |

| social networks | - |

| cultural expression | - |

| feeling of belonging | - |

| feeling of community | - |

| safety | nuisance (combined index) order disturbance abolishment violent crimes robberies burglaries |

| well-being | - |

| existence of informal groups and associations | - |

| representation by local governments | - |

| levels of participation | - |

| levels of influence | - |

References

- European Commission. Urban. Agenda for the EU; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- EUROCITIES. A Better Quality of Life for All—Eurocities’ Strategic Framework 2020–2030. Available online: https://eurocities.eu/about-us/a-better-quality-of-life-for-all-eurocities-strategic-framework/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Urban Land Institute. Zooming in on the “S” in ESG: A Road Map for Social Value in Real Estate; Urban Land Institute: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Musterd, S.; Marcińczak, S.; van Ham, M.; Tammaru, T. Socioeconomic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 1062–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersen, H.T. Governing European Cities: Social Fragmentation, Social Exclusion and Urban; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wennekers, A.; Boelhouwer, J.; Campen, C.; Kullberg, J. De Sociale Staat van Nederland 2019; Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Justitie en Veiligheid. Maatschappelijke Onrust Neemt Toe. Available online: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/ministeries/ministerie-van-justitie-en-veiligheid/strategische-documenten/centrale-eenheid-strategie/maatschappelijke-samenhang/maatschappelijke-onrust-neemt-toe (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Manzi, T.; Lucas, K.; Jones, T.L.; Allen, J. Social Sustainability in Urban Areas: Communities, Connectivity and the Urban Fabric; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T. Measuring Socially Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Europe; Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Larimian, T.; Sadeghi, A. Measuring urban social sustainability: Scale development and validation. Environ. Plan. B Urban. Anal. City Sci. 2019, 48, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiu, R.L. 12 Social Sustainability, Sustainable Development and Housing Development. In Housing and Social Change: East-West Perspectives; Forrest, R., Lee, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 221–239. [Google Scholar]

- Moroni, S. The just city. Three background issues: Institutional justice and spatial justice, social justice and distributive justice, concept of justice and conceptions of justice. Plan. Theory 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Alfred, A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littig, B.; Griessler, E. Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Langergaard, L.L. Interpreting ‘the social’: Exploring processes of social sustainability in Danish nonprofit housing. Local Econ. 2019, 34, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. Critical reflections on the theory and practice of social sustainability in the built environment—A meta-analysis. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1526–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davidson, M. Social sustainability and the city. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M. A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Sustainability 2012, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dempsey, N.; Brown, C.; Bramley, G. The key to sustainable urban development in UK cities? The influence of density on social sustainability. Prog. Plan. 2012, 77, 89–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingaertner, C.; Moberg, A. Exploring Social Sustainability: Learning from Perspectives on Urban Development and Companies and Products. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rashidfarokhi, A.; Yrjänä, L.; Wallenius, M.; Toivonen, S.; Ekroos, A.; Viitanen, K. Social sustainability tool for assessing land use planning processes. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1269–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitelaar, E. Maximaal, Gelijk, Voldoende, Vrij; Trancity*Valiz: Haarlem, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman, A.; Janssen-Jansen, L. Identifying distributive injustice through housing (mis) match analysis: The case of social housing in Amsterdam. Hous. Theory Soc. 2018, 35, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, B. Essential Injustice: When Legal Institutions Cannot Resolve Environmental and Land Use Disputes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G.; Dempsey, N.; Power, S.; Brown, C. What is ‘social sustainability’, and how do our existing urban forms perform in nurturing it? In Proceedings of the Planning research conference, London, UK, 3 April 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hamiduddin, I. Social sustainability, residential design and demographic balance: Neighbourhood planning strategies in Freiburg, Germany. Town Plan. Rev. 2015, 86, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. The triad of social sustainability: Defining and measuring social sustainability of urban neighbourhoods. Urban. Res. Pract. 2019, 12, 448–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dixon, T.; Woodcraft, S. Creating strong communities–measuring social sustainability in new housing development. Town Ctry. Plan. 2013, 82, 473–480. [Google Scholar]

- Robeyns, I. The capability approach in practice. J. Political Philos. 2006, 14, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Equality of what? Tanner Lect. Hum. Values 1979, 1, 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S. Why the capability approach? J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasper, D. What is the capability approach? Its core, rationale, partners and dangers. J. Socio-Econ. 2007, 36, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frediani, A.A. Sen‘s Capability Approach as a framework to the practice of development. Dev. Pract. 2010, 20, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Unterhalter, E. Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach and Social Justice in Education; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brummel, A. Sociale Verbinding in de Wijk. Mogelijkheden voor Sociale Inclusie van Wijkbewoners Met Een Lichte Verstandelijke Beperking of Psychische Aandoening; Delft Academische Uitgeverij Eburon: Delft, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Biagi, B.; Ladu, M.G.; Meleddu, M. Urban quality of life and capabilities: An experimental study. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Hickman, R. Urban transport and social inequities in neighbourhoods near underground stations in Greater London. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2019, 42, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, I. Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice: The Capability Approach Re-Examined; Open Book Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Basta, C. On Marx’s human significance, Harvey’s right to the city, and Nussbaum’s capability approach. Plan. Theory 2017, 16, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadin, V.; Stead, D. European Spatial Planning Systems, Social Models and Learning. Plan. Rev. 2008, 44, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuiling, D. Stadsvernieuwing door de jaren heen. Rooilijn 2007, 40, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Platform31. Kennisdossier Krachtwijkenbeleid: Afronding en Evaluatie. Available online: https://www.platform31.nl/wat-we-doen/kennisdossiers/stedelijke-vernieuwing/zeventig-jaar-stedelijke-vernieuwing/afronding-en-evaluatie (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Uyterlinde, M.; van der Velden, J.; Gastkemper, N. Zeventig Jaar Stedelijke Vernieuwing; Platform31: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Permentier, M.; Kullberg, J.; van Noije, L. Werk AAN de Wijk; SCP: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Uyterlinde, M.; van der Velden, J.; Bouwman, R. Wijk in Zicht: Kwalitatief Onderzoek Naar de Dynamiek van Leefbaarheid in Kwetsbare Wijken; Platform31: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Engbersen, G.; Snel, E.; der Boom, J. De Adoptie van Wijken; Erasmus Universiteit/RISBO Contractresearch: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Musterd, S.; Ostendorf, W. Integrated urban renewal in The Netherlands: A critical appraisal. Urban. Res. Pract. 2008, 1, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoekstra, J. Reregulation and Residualization in Dutch social Housing: A critical Evaluation of new Policies. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2017, 4, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nieboer, N.; Gruis, V. The continued retreat of non-profit housing providers in the Netherlands. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2016, 31, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leidelmeijer, K.; Marlet, G.; Ponds, R.; Schulenberg, R.; van Woerkens, C.; van Ham, M. Leefbarometer 2.0: Instrumentontwikkeling; RIGO Research en Advies & Atlas voor Gemeenten: The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hochstenbach, C. Dit Discriminerende Meetinstrument Bepaalt Overheidsbeleid. Available online: https://www.vpro.nl/programmas/tegenlicht/lees/artikelen/2020/leefbaarometer.html (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Leijdelmeijer, K.; Frissen, J.; van Iersel, J. Veerkracht in het Corporatiebezit; Aedes: The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Heurkens, E.; Hobma, F.; Verheul, W.J.; Daamen, T. Financiering van Gebiedstransformatie; Programma Stedelijke Transformatie/Platform31: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ham, M.; Manley, D.; Bailey, N.; Simpson, L.; Maclennan, D. Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives. In Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives; van Ham, M., Manley, D., Bailey, N., Simpson, L., Maclennan, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, P. Are mixed community policies evidence based? A review of the research on neighbourhood effects. In Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 267–294. [Google Scholar]

- Raad voor de Leefomgeving en Infrastructuur Toegang Tot de Stad; RLI: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2020.

- McClymont, K. Stuck in the Process, Facilitating Nothing? Justice, Capabilities and Planning for Value-Led Outcomes. Plan. Pract. Res. 2014, 29, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tangible | Intangible |

|---|---|

| decent housing | social interaction |

| transport | social networks |

| daily facilities | cultural expression |

| recreation | feeling of belonging |

| jobs | feeling of community |

| schools | safety |

| public spaces | well-being |

| healthcare | existence of informal groups and associations |

| urban design | representation by local governments |

| levels of participation | |

| levels of influence |

| Social Sustainability | Leefbaarometer | |

|---|---|---|

| Tangible | decent housing | housing quality; housing typology; housing tenure |

| transport | distance to train station and to highway; | |

| daily facilities | number of shops; distance to ATM | |

| recreation | day recreation facilities; number of cafes, restaurants and shops; distance to library; number of stages; distance to swimming pool; proximity to parks and natural areas | |

| jobs | - | |

| schools | number of primary schools | |

| public spaces | - | |

| healthcare | number of general practitioners; distance to hospital | |

| urban design | - | |

| - | demographics | |

| - | mutation rate | |

| Intangible | social interaction | - |

| social networks | - | |

| cultural expression | socio-cultural facilities | |

| feeling of belonging | - | |

| feeling of community | - | |

| safety | nuisance; order disturbance; abolishment; violent crimes; robberies; burglaries | |

| well-being | - | |

| existence of informal groups and associations | - | |

| representation by local governments | - | |

| levels of participation | - | |

| levels of influence | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janssen, C.; Daamen, T.A.; Verdaas, C. Planning for Urban Social Sustainability: Towards a Human-Centred Operational Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9083. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169083

Janssen C, Daamen TA, Verdaas C. Planning for Urban Social Sustainability: Towards a Human-Centred Operational Approach. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):9083. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169083

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanssen, Céline, Tom A. Daamen, and Co Verdaas. 2021. "Planning for Urban Social Sustainability: Towards a Human-Centred Operational Approach" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 9083. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169083

APA StyleJanssen, C., Daamen, T. A., & Verdaas, C. (2021). Planning for Urban Social Sustainability: Towards a Human-Centred Operational Approach. Sustainability, 13(16), 9083. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169083