1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has deeply affected education, as over 1.59 billion students could not go back to school [

1]. To cope with school closures and maintain education from home, several universities worldwide have shifted from face-to-face to remote teaching. Hodges et al. [

2] defined remote teaching as “a temporary shift of instructional delivery to an alternate delivery mode due to crisis circumstances. It involves the use of fully remote teaching solutions for instruction or education that would otherwise be delivered face-to-face or as blended or hybrid courses, and that will return to that format once the crisis or emergency has abated”. However, the lack of quality teaching resources [

3] and social interaction and innovative learning strategies [

4,

5,

6] has raised significant challenges in conducting online education, which made the students reluctant about taking online courses in this exceptional pandemic and during the post-pandemic period and negatively affected their perception of online education.

On the other hand, many studies have pointed out the importance of integrating playful teaching, as it arouses students’ attitudes and increases their engagement in online learning, thereby positively affecting their learning experience and outcomes [

7]. Other studies have shown that university support, in the form of policies, training, etc., could promote the adoption of online learning, especially in emergencies [

8,

9]. While massive research studies have been published during the COVID-19 pandemic, most of them focused on the advantages and challenges of remote/online education [

5,

6,

10,

11] without paying too much attention to what facilitates the adoption of online education in crises which could enhance the adoption of online education in the future and also in emergencies where no other options could be found. Remarkably, this study uses the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to investigate the impact of university students’ participation intention (PI) in online education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.1. Literature Review

Providing online learning was one of the solutions to maintain education from home during the COVID-19 pandemic [

12], as online learning is not limited by time and space [

13], allowing students and teachers to participate anywhere at any time [

6]. Notably, teachers and students can share their points of view and communicate online through text, pictures, videos, etc. [

14]. Additionally, students can view courses in advance and practice knowledge points they have not mastered through online learning [

5].

Although online learning could be a good solution in crises, Huang et al. [

6] pointed out that teachers and students can face several challenges in this first-ever application of pure long-term online learning (without face-to-face learning or blended learning), including students’ boredom, social isolation and a lack of engaging pedagogies. Several researchers have suggested implementing the playfulness concept when providing online learning experiences [

15]. Playfulness is defined as the subjective level of enjoyment felt by the learner [

16], which consists of five components: creativity, curiosity, humor, pleasure, and initiative [

17], and includes many fun activities, like teasing, imitating, and sharing [

18]. Playfulness provides students with a sense of security and a creative atmosphere. Many teachers consider it a core educational process, given the positive effects of playfulness on teaching effectiveness [

19]. For instance, playful learning can make the learning experience more fun and engaging [

20], resulting in better learning outcomes [

21]. Playful activities are also incorporated into early childhood education to motivate kids to learn and enhance their interest in a particular subject [

18]. Furthermore, perceptual playfulness can also help increase the willingness to use instructional management systems [

7]. However, current empirical studies on perceived playfulness and university support in online learning in a crisis are scarce.

In addition to an excellent online learning experience design, several research studies have pointed out that university support to adopt online learning is crucial for a successful shift from offline to online learning, especially in crises [

3]. For example, Ali [

22] and Demuyakor [

23] pointed out that providing information and communication technology support can provide a good foundation for a successful online learning process and reduce teachers’ workload. Robust digital learning systems can also enhance universities’ teaching and learning practices, especially in emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic [

11]. Aguilera-Hermida [

9] argued that students are actively involved in online learning when supported by technology and resources to make the online learning activities run more smoothly. University support can make online learning more enjoyable for college students by providing, for instance, stable Internet connections, technical support, and adapted learning tools [

24], which have a positive effect on the students’ adoption of online learning [

25].

1.2. Research Gap

As discussed above, although several studies have pointed out the importance of playfulness and university support in typical situations (i.e., not in crises or emergencies), no research study, to the best of our knowledge, discussed these two elements, namely playfulness and university support, in emergencies and how they could be helpful for teachers to shift from face-to-face to online learning rapidly. In this context, several organizations and scholars have pointed out the need to investigate the design of future education in times of uncertainties and emergencies [

1,

3,

6,

24]. In line with this, this study aims to investigate how playfulness and university support could facilitate students’ adoption of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Adedoyin and Soykan [

26], Ali [

22], Bao [

3], Dai D and Lin [

12], Dhawan [

27], and Zhou et al. [

5] analyzed the necessity, application strategies, and opportunities faced by online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic through a review of previous literature. Several scholars have focused on the importance of online learning during COVID-19 and investigated college students’ views, use, performance, and attitude during online learning during COVID-19 without a theoretical framework [

9,

23,

24,

28]. It can be concluded from the above research that, despite the vast body of research investigating students’ adoption of online learning during the COVID-19, few studies used theoretical frameworks to discuss their results [

9,

23,

24,

28], which makes their conclusions and insights more limited (i.e., specific to their context) and hard to be reproduced. Therefore, this study uses the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to explore the factors affecting students’ participation intention in online education. TAM was proposed by Davis et al. [

29] and is widely used in research on various online education platforms, shopping websites, and business offices. According to a large number of literature searches and content analyses, TAM is also used in a large number of empirical studies to explore users’ participation intention [

30,

31,

32].

In the context of COVID-19, Almaiah et al. [

8] determined the factors influencing the adoption of online learning through an interview method, Al Kurdi et al. [

13] studied the usage behavior of college students using the SEM method, Thongsri et al. [

25] studied the determinants of online learning adoption based on a hybrid SEM. However, none of the above empirical studies focused on students’ intention to participate, and neither did they include perceived playfulness. Playfulness [

33,

34] and university support [

35,

36,

37] are important for optimizing online education’s effects. Departing from the current research, this study will also consider the mediating effect of the online learning participation attitude (PA) and the moderating effect of university support to obtain more research findings and practical enlightenment to improve the effectiveness of online education.

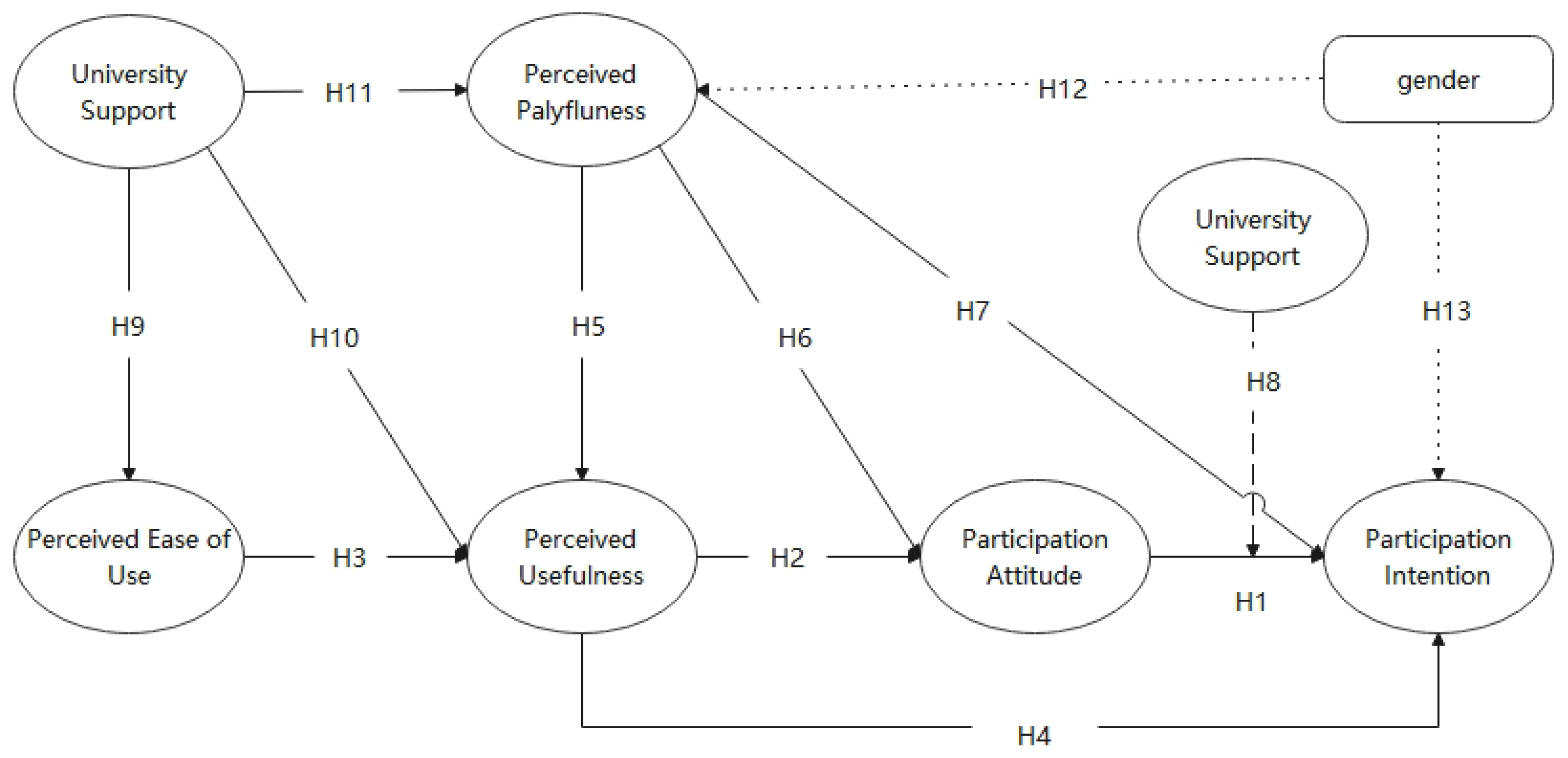

2. Hypothesis

This study focuses on the influencing factors of university students’ participation intention in online education by using TAM as the research framework, introducing university supports, constructing research models, exploring the effects of perceived usefulness, ease of use, and playfulness on online education participation attitudes, and then discussing how participation attitudes influence the participation intention in online education while verifying the mediation role of participation attitude and the regulatory influence of university support.

In the model of this study, an attitude refers to the individual’s subjective judgment of specific behavior. Attitude is an important variable, that drives behavioral intentions [

29]. A good attitude is an essential factor for an individual to develop a particular behavioral participation intention [

38]. Huang et al. [

39] conducted research on mobile learning behavior based on the TAM model and confirmed that behavior attitude significantly affects behavior intention. Teo and Zhou [

40] believe that attitude is the most potent predictor of using new technologies. In a MOOC study with Chinese subjects as sample, it was found that the subjects’ attitudes towards MOOC and perceived behavior control had a significant impact on their participation intention to continue using it [

41]. Baydas [

42] collected data from 276 pre-service teachers, analyzed them through structural equation models and found that pre-service teachers’ learning attitude and cognitive needs significantly impact their participation intention in online learning. The positive influence of behavior attitude on behavior intention has been verified in many studies [

43,

44,

45]. Based on the above analysis, participation intention reflects the participation intention of university students to participate in online education and is a necessary condition for university students to take action. Therefore, the hypotheses proposed in this study are as follows:

Hypothesis 1. Participation attitude has a positive effect on university students’ participation intention in online education.

In this study, Perceived Usefulness (PU) refers to the subjective judgment that university students’ participation in online educational activities will enhance or improve university students’ learning effects, make learning more effective, and gain more knowledge. Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) refers to university students’ perception of whether the online education platform is easy to use or of the effort required [

46]. Huang et al. [

47] found that usefulness has a positive effect on the participation intention to use in a study on mobile learning with undergraduates. Wu and Zhang’s [

48] research found that the perceived ease of use has a crucial impact on users’ attitudes and perceived usefulness of online learning systems. Safsouf et al. [

34] concluded that the perceived ease of use and usefulness have a significant impact on behavior intention, and this conclusion is similar to the results of related TAM studies. Rafique et al. [

49] found through research that perceived usefulness positively affects the behavioral participation intention to learn online. Based on the above analysis, the hypotheses proposed in this study are as follows:

Hypothesis 2. Perceived Usefulness has a positive effect on participation attitude.

Hypothesis 3. Perceived Ease of Use has a positive effect on perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 4. Perceived Usefulness has a positive effect on university students’ participation intention in online education.

This study identified Perceived Playfulness (PP) as the pleasure and interest of university students participating in online education. According to the self-determination theory, internal motivation refers to individual participating in, and accomplishing something related to his inner interests and beliefs [

50]. At present, PP has been widely introduced into online education research. If users are truly interested in learning a given content or have a firm belief in their ability to complete a given course, their participation intention will also increase. The design of a digital learning system requires more playfulness integration [

51]. Huang et al. [

39] confirmed that perceptual playfulness significantly affects attitudes in mobile learning research. Teo and Noyes [

52] conducted research based on TAM and found that perceived playfulness is an essential predictor of perceived ease of use, usefulness, and behavioral participation intention. Alraimi et al. [

33] believe that playfulness is intrinsically motivating and significantly impacts users’ behavioral intentions. Sarrab et al. [

15] investigated the acceptance factors of mobile learning based on TAM and found that ease of use, practicality, and playfulness greatly impact learners’ participation in online learning. Safsouf et al. [

34] found that the PP of online learners indirectly affects usefulness, behavior, and attitudes through PEU. Based on the above analysis, the hypotheses proposed in this study are as follows:

Hypothesis 5. Perceived playfulness has a positive effect on perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 6. Perceived playfulness has a positive effect on participation attitude.

Hypothesis 7. Perceived playfulness has a positive effect on participation intention.

This study’s University Support (US) refers to the relevant supporting policies and management systems for online education in the colleges and universities to which the students belong. Davis and Murrell [

53] believe that the support provided by colleges and universities can enhance students’ participation intention. Venkatesh and Bala [

35] believe that the external social environment will affect the individual’s participation intention to use the information system. Schierz et al. [

54] pointed out that the effects of the outside world and the influence of other people will cause changes in individual thoughts, attitudes, or behaviors. Lakhal et al. [

36] found that external promotion conditions and social influence are also important driving forces for behavioral intentions. Tosuntaş et al. [

37] found that the school’s external support positively affects the participation intention to use. Against the background of the credit system, students may have different learning attitudes when participating in online education. Students’ perception of the degree of support for online education by colleges and universities may also affect their attitudes toward participation in online education. The publicity of online education policies will affect university students’ views and behavioral wishes on implementing “stop classes without suspension.” “University support” will examine the system introduced by colleges and universities to develop online education from three aspects: credit certification, promotion, and support and guarantee. Based on the above analysis, the hypotheses proposed in this study are as follows:

Hypothesis 8. University support has a positive moderation effect on the participation attitude of university students in online education to their participation intention.

Hypothesis 9. University Support has a positive effect on perceived ease of use.

Hypothesis 10. University Support has a positive effect on perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 11. University Support has a positive effect on perceived playfulness.

Hypothesis 12. The different genders have different perceptual playfulness.

Hypothesis 13. The different genders have different participation intentions.

The 13 hypotheses proposed in this study are shown in

Figure 1.