Youth Participation in Agriculture: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (i)

- Identify the existing challenges and opportunities for youth in agriculture in Africa;

- (ii)

- Based on the evidence, propose an integrated agricultural-based approach for promoting youth participation and inclusivity in agriculture and the future food system in Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Challenges and Opportunities for Youth in Agriculture

3.3. Youth Aspirations, Interest and Participation in Agriculture

3.4. Role of Youth in the Food System

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

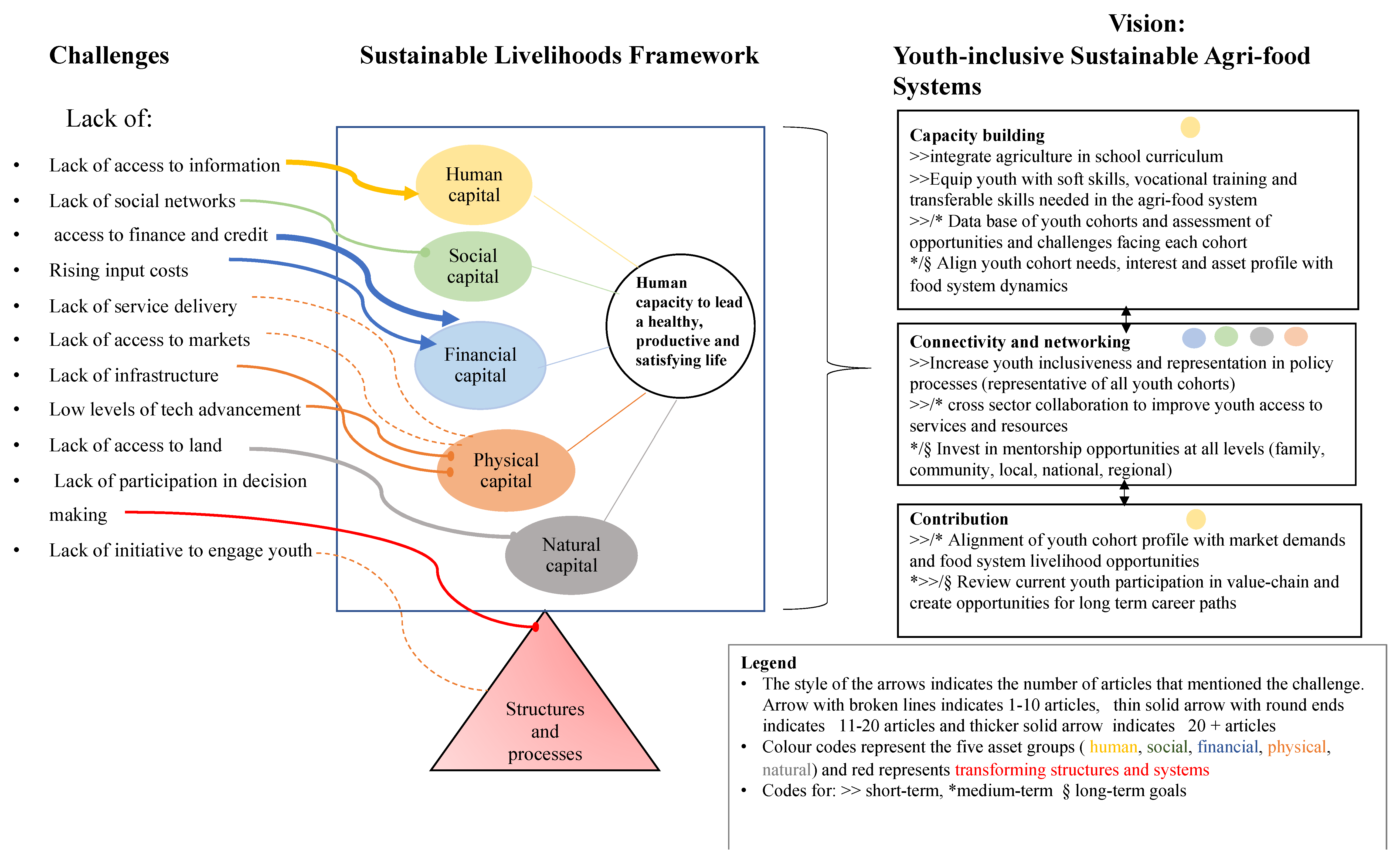

6. Way Forward: The Role of Youth in Future Food Systems

- The exposure to agricultural studies at secondary and tertiary level could influence youth’s intention to participate in agripreneurship. This will expose youths to the full range of career options in the agricultural sector at earlier stages. This is being carried out in Zambia through the UniBRAIN program by promoting agricultural innovation and improving tertiary agribusiness education in Africa. In South Africa, the Junior LandCare programme creates an environment for school children to participate in sustainable agriculture activities through food gardens that supplement the school feeding scheme.

- National agricultural policies need to account for youth aspirations, contributing factors, challenges facing youth under different contexts, and characterise data based on age groups. This will assist in developing youth tailored initiatives relevant to the context.

- For youths who are inclined to work in agriculture, high-potential value chains that align with their aspirations and have the potential for increased economic returns should be identified, including the provision of support and removing barriers for youth participation, for example, the YEAP program in Nigeria and Youth Agropastoral Entrepreneurship Programme in Cameroon. These initiatives are creating decent employment opportunities along the agricultural value chain for youths in rural areas. Initiatives can be facilitated through the implementation of regional policies such as the Malabo declaration and Agenda 2063.

- For youths who are not inclined to work in the farm, including those without access to land and production resources, mobilization of support through government and the private sector could position these youths in nonfarm activities that drive agricultural transformation and the improvement of rural markets. For example, marketing and trading of agricultural related products.

- Regional strategies for developing the agricultural value chain (for example the SADC Regional Agricultural Policy) must mainstream youth considerations, with the objective of youth inclusion, capacity development, and sustainable employment opportunities. There is a need for more deliberate investments to be made to create opportunities for youth throughout the value chain.

- Efforts must be made to create a supportive environment to increase opportunities through which youths can pursue food system-related careers and interests. This can be achieved through increasing social capital, improving youths’ connectivity to value-chain actors, promoting networking, peer-to-peer learning, raising awareness, mentorship, and other forms of linkages.

- Modernisation of agricultural production systems and promoting the development of local value-chains to increase awareness, provoke youth interest, and establish relevant role models. Additionally, the design of national policies should explicitly support informal businesses in rural and peri-urban areas.

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Youth Employment in Agriculture as a Solid Solution to Ending Hunger and Poverty in Africa. 2018. Available online: http://www.fao.org/about/meetings/youth-in-agriculture/en/ (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Mueller, V.; Thurlow, J. Africa’s Rural Youth in the global Context. In Youth and Jobs in Rural Africa; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Proceeding of The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, A.D. African Economic Outlook Chapter 2: Jobs, Growth and Firm Dynamism. 2019. Available online: https://www.icafrica.org/fileadmin/documents/Publications/AEO_2019-EN.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Castañeda, A.; Doan, D.; Newhouse, D.; Nguyen, M.C.; Uematsu, H.; Azevedo, J.P.; World Bank Data for Goals Group. A new profile of the global poor. World Dev. 2018, 101, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, D.; Goedhuys, M. Youth Aspirations and the Future of Work a Review of the Literature and Evidence; ILO Working Papers: Geneva, Swizerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dercon, S.; Gollin, D. Agriculture in African development: Theories and strategies. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2014, 6, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, K.; Zorya, S.; Gautam, A.; Goyal, A. Agriculture as a Sector of Opportunity for Young People in Africa; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Akinnifesi, F.K. Can South-South Cooperation offer sustainable agriculture-led solutions to youth unemployment in Africa? Nat. Faune 2013, 28, 19. [Google Scholar]

- African Union. The African Youth Decade 2009–2018 Plan of Action. In Accelerating Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development-Road Map towards the Implementation of the African Youth Charter; African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NEPAD. Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme; New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD): Midrand, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Global Partnership for Youth Employment. Promoting Agricultural Entrepreneurship among Rural Youth. 2014. Available online: https://iyfglobal.org/sites/default/files/library/GPYE_RuralEntrepreneurship.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- AGRA. Africa Agriculture Status Report. Feeding Africa’s Cities: Opportunities, Challenges, and Policies for Linking African Farmers with Growing Urban Food Markets 2020; Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA): Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation. Youth E–Agriculture Entrepreneurship; Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidu, K. Entrepreneurship Intention and Involvement in Agribusiness Enterprise among Youths in Gombe Metropolis, Gombe State, Nigeria: Potentials of Agribusiness in Nigeria. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 2015, 5, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chinsinga, B.; Chasukwa, M. Youth, agriculture and land grabs in Malawi. IDS Bull. 2012, 43, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindsjö, K.; Mulwafu, W.; Djurfeldt, A.A.; Joshua, M.K. Generational dynamics of agricultural intensification in Malawi: Challenges for the youth and elderly smallholder farmers. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sumberg, J.; Yeboah, T.; Flynn, J.; Anyidoho, N.A. Young people’s perspectives on farming in Ghana: A Q study. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Checkoway, B. What is youth participation? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinsinga, B.; Chasukwa, M. Agricultural policy, employment opportunities and social mobility in rural Malawi. Agrar. South J. Political Econ. 2018, 7, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeboah, F.K.; Jayne, T.S. Africa’s evolving employment trends. J. Dev. Stud. 2018, 54, 803–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, A.-A. Understanding Farming Career Decision Influencers: Experiences of Some Youth in Rural Manya Krobo, Ghana. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2015, 7, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auta, S.J.; Abdullahi, Y.M.; Nasiru, M. Rural youths’ participation in agriculture: Prospects, challenges and the implications for policy in Nigeria. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2010, 16, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadzamira, M.A.; Kazembe, C. Youth engagement in agricultural policy processes in Malawi. Dev. South. Afr. 2015, 32, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwebel, D.; Estruch, E. Policies for Youth Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Youth and Jobs in Rural Africa: Beyond Stylized Facts; IFPRI; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Betcherman, G.; Khan, T. Jobs for Africa’s expanding youth cohort: A stocktaking of employment prospects and policy interventions. IZA J. Dev. Migr. 2018, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ILO. Youth Employment Interventions in Africa: A Mapping Report of the Employment and Labour Sub-Cluster of the Regional Coordination Mechanism (RCM) for Africa; International Labour Organization: Addis Ababa, Ethopia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ayinde, J.O.; Torimiro, D.O.; Koledoye, G.F.; Adepoju, O.A. Assessment Of Rural Youth Involvement In The Usage Of Information And Communication Technologies (Icts) Among Farmers’in Osun State, Nigeria. Sci. Pap. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2015, 15, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Amsler, K.; Hein, C.; Klasek, G. Youth Decision Making in Agricultural Adaptation to Climate Change; CCAFS Working Paper no. 206; CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; PRISMA-P Group; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; The PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trivelli, C.; Morel, J. Rural Youth Inclusion, Empowerment, and Participation. J. Dev. Stud. 2020, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q-International. NVivo 11 for Windows: Getting Started Guide. 2015. Available online: http://download.qsrinternational.com/Document/NVivo11/11.3.0/en-US/NVivo11-Getting-Started-Guide-Pro-edition.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2015).

- Flanagan, S.M.; Greenfield, S.; Coad, J.; Neilson, S. An exploration of the data collection methods utilised with children, teenagers and young people (CTYPs). BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheteni, P. Youth participation in agriculture in the Nkonkobe district municipality, South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 55, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsson, I.; Staland-Nyman, C.; Svedberg, P.; Nygren, J.M.; Carlsson, I.-M. Children and young people’s participation in developing interventions in health and well-being: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayinde, J.O.; Olatunji, S.O.; Ajala, A.O. Assessment of rural youth adoption of cassava production technologies in Southwestern Nigeria. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2018, 18, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kidido, J.K.; Bugri, J.T.; Kasanga, R.K. Dynamics of youth access to agricultural land under the customary tenure regime in the Techiman traditional area of Ghana. Land Use Policy 2017, 60, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naamwintome, B.A.; Bagson, E. Youth in agriculture: Prospects and challenges in the Sissala area of Ghana. Net. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 1, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nwankwo, O. Major Factors Militating against Youths Participation in Agricultural Production in Ohafia Local Government Area of Abia State, Nigeria. J. Environ. Issues Agric. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 6, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Adeogun, S.O. Participatory diagnostic survey of constraints to youth involvement in cocoa production in cross river state of Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 60, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusa, P.M.; Giroh, D.Y. Determinants of Youth Participation in Food Crops Production in Song Local Government Area of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2017, 17, 427–434. [Google Scholar]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Simpson, G. Assessing the State of the Water-Energy-Food (WEF) Nexus in South Africa; WRC Report No KV 365/18; Water Research Commission; University of KwaZulu-Natal: Durban, South Africa, 2018; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- SADC. Regional Agricultural Policy; Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources (FANR) Directorate: Gaborone, Botswana, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- African Union. Agenda 2063 Report of the Commission on the African Union Agenda 2063 The Africa We Want in 2063; African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mukembo, S.C.; Edwards, M.C.; Ramsey, J.W.; Henneberry, S.R. Intentions of Young Farmers Club (YFC) Members to Pursue Career Preparation in Agriculture: The Case of Uganda. J. Agric. Educ. 2015, 56, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falola, A.; Ayinde, O.E.; Ojehomon, V.E. Economic analysis of rice production among the youths in Kwara State, Nigeria. Albanian J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 12, 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Agboola, A.; Adekunle, I.; Ogunjimi, S. Assessment of youth participation in indigenous farm practices of vegetable production in Oyo State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext. Rural. Dev. 2015, 7, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Emmanuel, F.O.; Olaseinde, A.T. Assessing the future of agriculture in the hands of rural youth in oriade local government area of osun state, Nigeria. Int. J. Agric. Ext. 2016, 4, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Adesina, T.K.; Favour, E. Determinants of participation in youth-in-agriculture programme in Ondo state, Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext. 2016, 20, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okon, D.; Nsa, S. Determinants of sustained youth participation in fishing in Mbo Local Government Area of Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Biotechnol. Ecol. 2012, 5, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ayinde, J.; Olarewaju, B.; Aribifo, D. Perception of youths on government agricultural development programmes in Osun State, Nigeria. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2016, 16, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Carreras, M.; Sumberg, J.; Saha, A. Work and Rural Livelihoods: The Micro Dynamics of Africa’s ‘Youth Employment Crisis’. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00310-y (accessed on 7 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Townsend, R.B.R.; Prasann, A.; Maria, L. Future of Food: Shaping the Food System to Deliver Jobs; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Internation Labour Organization. World Employment and Social Outlook Trends 2020; Internation Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen, M.; van Emmerik, H.; Van Gils, A.; Meng, C.; de Grip, A. Does early-career underemployment impact future career success? A path dependency perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 90, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serrat, O. The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach, in Knowledge Solutions; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda-Parr, S. The human development paradigm: Operationalizing Sen’s ideas on capabilities. Fem. Econ. 2003, 9, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frediani, A.A. Sen’s Capability Approach as a framework to the practice of development. Dev. Pract. 2010, 20, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Challenge of Capacity Development: Working Towards Good Practice; OECD: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Future of Rural Youth in Developing Countries: Tapping the Potential for Local Value Chains; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dewbre, J.; Cervantes-Godoy, D.; Sorescu, S. Agricultural Progress and Poverty Reduction: Synthesis Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bezu, S.; Holden, S. Are Rural Youth in Ethiopia Abandoning Agriculture? World Dev. 2014, 64, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maina, W.N.; Maina, F.M.P. Youth Engagement in Agriculture in Kenya: Challenges and Prospects. J. Cult. Soc. Development 2015, 7, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, M.S.; Harttgen, K. What Is Driving the ‘African Growth Miracle’? National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; CTA; IFAD. Youth and Agriculture: Key Challenges and Concrete Solutions; FAO: Rome, Italy; CTA: Rome, Italy; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Magagula, B.; Tsvakirai, C.Z. Youth perceptions of agriculture: Influence of cognitive processes on participation in agripreneurship. Dev. Pract. 2020, 30, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IFPRI. 2020 Global Food Policy Report: Building Inclusive Food Systems; IFPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, S.F.; Hamilton, M.A. The Youth Development Handbook: Coming of Age in American Communities, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, D.; Sumberg, J. Youth and food systems transformation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Policy | Challenges Faced by Youth | Youth Role and Participation in Agriculture | Youth Investment Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| African Youth Charter | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

|

| African Youth Decade Plan of Action |

| Not mentioned |

|

| Agenda 2063 |

| Not mentioned |

|

| CAADP | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Malabo Declaration | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

|

| SADC Regional Agricultural Policy | youth is poor, rural, has poor access to economic activities, education, land and capital. | Participation for most of the rural youth in farming is based on circumstances and limited economic opportunities |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geza, W.; Ngidi, M.; Ojo, T.; Adetoro, A.A.; Slotow, R.; Mabhaudhi, T. Youth Participation in Agriculture: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9120. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169120

Geza W, Ngidi M, Ojo T, Adetoro AA, Slotow R, Mabhaudhi T. Youth Participation in Agriculture: A Scoping Review. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):9120. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169120

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeza, Wendy, Mjabuliseni Ngidi, Temitope Ojo, Adetoso Adebiyi Adetoro, Rob Slotow, and Tafadzwanashe Mabhaudhi. 2021. "Youth Participation in Agriculture: A Scoping Review" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 9120. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169120

APA StyleGeza, W., Ngidi, M., Ojo, T., Adetoro, A. A., Slotow, R., & Mabhaudhi, T. (2021). Youth Participation in Agriculture: A Scoping Review. Sustainability, 13(16), 9120. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169120