Abstract

This study examined the effects of workplace flexibility at deluxe hotels on work engagement, satisfaction, and commitment, to determine the moderating effect of generational characteristics (Generation X, Y, and Z). A total of 277 deluxe hotel employees in South Korea participated in the research. The results confirmed the positive effects of workplace flexibility on the engagement and satisfaction of deluxe hotel employees; second, employees’ work engagement had a positive effect on their satisfaction; third, employees’ satisfaction had a positive impact on employees’ commitment; and fourth, the influence of workplace flexibility on engagement did not differ by generation. However, Generation Z showed the largest increase in employee engagement resulting from work flexibility. This result signifies that, when compared to other generations, Generation Z places great importance on workplace flexibility. This study suggests that deluxe hotels should create flexible policies and organizational climates to increase employees’ work engagement, satisfaction, and commitment. The paper also discusses limitations and future research directions.

1. Introduction

Leaders should have clear insight into the characteristics of their workforce, from top management to entry-level employees, to succeed in the fast-paced world of management [1]. With the diversification of workforces and rapid changes in how tasks are delegated and performed, organizations are increasingly required to ensure employees’ positive engagement [2]. Workplace flexibility is a research concept that attracts attention because it is positively associated with organizational performance related to employee retention and commitment [3,4]. In addition, from an organizational perspective, workplace flexibility can represent an organization’s ability to improve organizational profitability through practices such as employment, quality, and job rotation [5]. Peter and Blomme [6] stated that workplace flexibility satisfies needs regarding when and where to work in consideration of personal, organizational, and economic performance in work and life; they argued that workplace flexibility should have significance in organizations because it satisfies individuals’ basic psychological needs. This flexibility reduces employee burnout [7], decreases stress, increases organizational commitment [8], and acts as a buffer against negative impacts [9] while playing a central role in employer strategies that companies adopt for important competitions through enhanced organizational performance [10].

It is an era in which work–life balance, which may be the basic concept of organizational flexibility, is manifested not only in the younger generations but also in elderly employees [11]. Workplace flexibility has become an increasingly popular concept since women entered a greater number of workplaces [12]. This is particularly true in deluxe hotels, given that they have relatively higher proportions of young and female employees. The composition and form of organizational workforces have changed extensively. It has become increasingly important to understand and manage the expectations of different generations [13]. Understanding generational similarities and differences serves as a foundation for opening the perspectives and demands of various generations and their thoughts about various employees [14]. Therefore, enhancing the understanding of the hospitality industry’s next generation of employees compared to the current generation is a vital value for managers and other leaders in the hospitality industry [15]. Capnary et al. [16] reported that many organizations are implementing strategies directed at increasing employee loyalty and satisfaction through work–life flexibility because these strategies are based on the unique characteristics of most employees who are millennials. Particularly from the perspective of life stages, other values can become more important over time. Ariza-Montes et al. [17] noted that human values in the hospitality industry vary according to different groups of employees.

As characteristics that emerge in generation-specific organizations, Generation X (born between 1965–1979) places great importance on career goals and professional growth opportunities [18], whereas Generation Y (born between 1980–1994) pursues autonomy at work and emphasizes transparency in communication [19]. Generation Z (born after 1995) values well-being and job flexibility in an organization as the most important factors [20]. Generation X was a leading generation in former organizations; however, Generation Y is present throughout the entry stage of the labor market, and Generation Z has now entered the declining workforce [21]. As a result, a more subtle approach is needed to understand how the work environment differs among Generation(s) X, Y, and Z.

Therefore, this study was based on the assumption that employees’ engagement, satisfaction, and commitment can vary depending on their perceptions of workplace flexibility, and this causal relationship varies depending on an employee’s generation (Generation X, Y, and Z).

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Hypothesis Development

Workplace flexibility is an opportunity for employees to make choices that influence when, where, and for how long they participate in work-related tasks [12]. It also refers to the extent to which employees can select and adjust key aspects of their work lives. When employees are granted the opportunity to use flexibility, they can secure more resources and better control their tasks to achieve work-related goals [22]. Engagement can be defined as an individual’s positive work-related state of mind characterized by energy and commitment regarding his/her job [23]. Saks [24] defined engagement as how much employees are passionately immersed in performing their roles, and suggested that workplace flexibility can promote engagement because it is directly linked to a reduction in interference [25]. Richman et al. [3] argued that perceived flexibility increases employee engagement. Ten Brummelhuis et al. [26] reported that employees exhibited an overall higher level of work engagement on the days they worked remotely or flexible work arrangements, including telecommuting and working via email. Timms et al. [27] asserted that company policies involving flexible work arrangements positively influence employees’ levels of work commitment and engagement. According to Ugargol and Patrick [28], a higher level of flexibility in the work environment leads employees to be enthusiastic and engaging.

Job satisfaction is the extent to which job demands are satisfied and how much this satisfaction is perceived by employees [29]. It also means positive emotional states that organizational members have about their jobs according to their attitudes, values, and beliefs [30]. There are studies related to workplace flexibility and job satisfaction. According to Burud and Tumolo [31], flexible work arrangements reduce stress and absenteeism and increase employee satisfaction. Kelliher and Anderson [32] reported that employees who had flexible work arrangements showed higher levels of job satisfaction than those who did not. Origo and Pagani [33] also found a positive correlation between work environment flexibility and job satisfaction. Masuda et al. [34] stated that, at the individual level, work–life flexibility is closely related to increased satisfaction and reduced stress. Managers who use flexible work arrangements frequently report that they are more satisfied with their jobs than managers who do not. Ma [35] reported that a higher level of workplace flexibility leads to a corresponding higher level of job satisfaction, and Neirotti et al. [36] noted that the adoption of flexible work arrangements has a positive impact on job satisfaction. Davidescu et al. [37] stated that it is essential to develop workplace flexibility, including flexibility in work hours and workspaces, to increase employees’ job satisfaction. According to Ray and Pana-Cryan [38], telecommuting as part of work flexibility lowered the likelihood of job stress and increased job satisfaction. Based on these previous studies’ findings, this study assumed that workplace flexibility would increase employees’ work engagement and satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1.

Workplace flexibility positively influences employees’ work engagement.

Hypothesis 2.

Workplace flexibility positively influences employees’ satisfaction.

In a study related to work engagement and satisfaction, Griffiths and Karanika-Murray [39] stated that employees who are absorbed in their jobs inevitably have high levels of satisfaction, because this means they are addicted to their work. Yeh [40] confirmed a positive relationship between employee participation and job satisfaction. Rayton and Yalabik [41] stated that because organizations will have increased costs due to unengaged employees, employee engagement is vital for an organization, and employee engagement and satisfaction have a very close relationship. Lu et al. [42] stated that job satisfaction can be increased by improving restaurant employees’ engagement. Orgambídez-Ramos and Almeida [43] reported that job satisfaction is the most important variable that predicts work engagement, and employees with greater engagement are more satisfied with their jobs and more dedicated and loyal to their organizations. Garg et al. [44] also noted that when employees have strong engagement and persistence along with increased motives, their job satisfaction also increases. According to Rayton et al. [45], work engagement and satisfaction have a positive correlation; thus, organizational roles for enhancing employee engagement are essential to creating job satisfaction. Gong et al. [46] demonstrated that employees’ engagement for work performance has a positive impact on their attitudes toward work processing and increases job satisfaction. Based on these studies’ results, this present study assumed that employees’ work engagement would increase their satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3.

Employees’ work engagement positively influences their satisfaction.

Commitment is the degree to which individual identify with the organization to which they belong and are dedicated [47]. This means that an organization’s members accept the organization’s goals and values and try to achieve them [48]. Given that studies related to job satisfaction and commitment have been verified by multiple studies, only a few important ones have been discussed in this present study. Eisenberger et al. [49] stated that employees who feel that their jobs are valuable and are satisfied with them reciprocate with positive attitudes and behaviors. According to Williams and Anderson [50], job satisfaction and commitment have a very positive correlation. Shahah and Nisa [51] also reported that job satisfaction has a positive and significant effect on organizational commitment, and Valaei and Rezaei [52] argued that higher levels of most factors of job satisfaction, such as wages, promotions, welfare, and relationships with colleagues, lead to correspondingly higher levels of employees’ affective commitment. Lee and Ok [53] stated that employees engaged in and satisfied with their jobs are highly likely to reward their organizations through effective dedication and commitment. Eliyana et al. [54] suggested that organizational members’ commitment is affected by their satisfaction, and Ampofo [55] also argued that hotel employees’ job satisfaction predicts their affective commitment. Therefore, the following hypothesis was posited:

Hypothesis 4.

Employees’ satisfaction positively influences employees’ commitment.

A generation is a group of people in the same age group who experience similar social events in similar social positions [56]. Therefore, an organization’s managers should understand and manage the values and behavioral patterns of their organization’s members generationally. In particular, the current generations often experience difficulties adapting to the authoritarian organizational culture represented; therefore, it is essential to understand an organization’s generational characteristics [57,58]. Bennett et al. [59] stated that there are clear differences between generations in an organization, and the effective transfer of knowledge between the more experienced generation and the younger generation should be ensured through mentoring, the provision of coworking spaces, and team-based organizations. McGuire et al. [13] found the existence of generational differences in approaches and attitudes toward work, which can cause various intergenerational conflicts that potentially undermine organizational performance. These researchers thus argued that new organizational cultures should respect and optimize for each generation. In this study, the former main generation, Generation X, and the current main generations, Generation Y and Generation Z, were separated and examined to verify the moderating effect of generations [60]. Although many studies have been conducted on Generation X and Generation Y [58,61,62], studies involving Generation Z are rare. According to Deloitte [63], Generation Z will account for 20% of the workforce over the next five years, representing a considerable portion of the labor market. The entry of this generation into the labor force, coupled with the retirement of the baby boomer generation, will bring significant changes to organizational cultures and environments [64]. Steelcase [65] suggested that for Generation X, work is a challenge and should be achieved within a contract, but it should not be done at the expense of family life, whereas Generations Y and Z pursue achievement and meaningfulness simultaneously through completely integrating work and life. Pitt-Catsouphes and Matz-Costa [66] found that when employees perceived the need for flexibility more keenly, they showed higher job participation levels, and those aged 45 or above showed a greater increase in participation. Consequently, the authors suggested a positive relationship between the two variables. They explained that this was probably because employees aged 45 or older were more devoted to their families than their younger colleagues. Kim et al. [67] stated that Generation Y, compared to Generation X, places more importance on their work environment and relationships with superiors and managers. They added that, because this generation highly values empowerment, it is important to create an environment in which they can make their own decisions and take on greater responsibilities [62]. Notably, they expected Generation Y to prefer a flexible work environment, given that they pursue flexibility and autonomy in their work-related achievements. Jung et al. [68] found that the negative influence of job instability on employee engagement was stronger in Generation Y than in Generation X, and a significant cause of Generation Y’s relatively low work engagement is that the goal of self-realization becomes obscure in a situation controlled by uncertainty. According to Sakdiyakorn et al. [15], as an organizational characteristic of Generation Z, universalism is the most important value shown in this generation; it prefers organizations that contribute to society and participate in prosocial behaviors. Schawbel [69] noted that Generation Z prefers organizational flexibility. Goh and Lee [70] stated that Generation Z, compared with other generations, responds more meaningfully to intrinsic motivations, such as excitement and a sense of achievement, and that organizations should focus on fulfilling their job-related aspects. Goh and Okumus [71] believe that equal opportunity, equality, and fairness form the most important foundations for an organization’s environment and that organizations should participate in sustainable practices to promote their engagement. This study assumed that employees’ perceptions of their workplace flexibility influence employees’ engagement, and this varies depending on the generation; in particular, a more recent generation of employees would experience a stronger influence of work flexibility on their engagement.

Hypothesis 5.

Employees’ generation moderates the effects of workplace flexibility on work engagement.

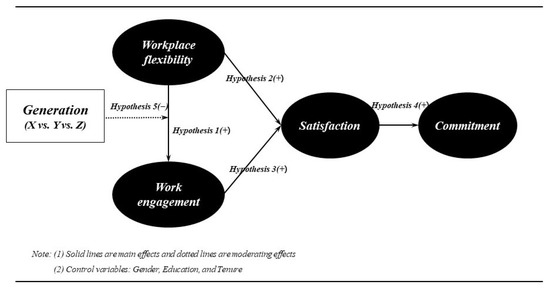

2.2. Research Model

As shown in Figure 1, workplace flexibility, work engagement, satisfaction, commitment, and employees’ generation are the independent, dependent, and moderating variables in this study.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

The population of this study for carrying out its activities was defined as employees working at deluxe hotels in Seoul, South Korea. The deluxe hotels selected as the sample of this study were limited to 5-star hotels with more than 200 bedrooms and providing comprehensive services. A survey was conducted by selecting five hotels in Seoul that allowed for this survey. A preliminary survey was performed one month before the main survey to correct or improve ambiguous or difficult-to-understand parts of the measurement items. During October 2020, 350 questionnaires were distributed: 70 questionnaires to each hotel. The researcher visited these hotels, explained the survey’s purpose, and conducted the survey using a self-report method of employees filling in the questionnaires themselves. After distribution, 326 questionnaires were collected, and 277 were used for the final analysis, excluding those that were not suitable for a double analysis.

3.2. Instrument Development

This study’s items were measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). A survey questionnaire produced in English was translated into Korean, as specified by Brislin [72]. The operational definition of each variable is mentioned in the theoretical background section, and the measurement items are as follows: The questionnaire consisted of six parts. First, the workplace flexibility as perceived by employees was measured. This study adapted Thomas and Ganster’s [73] and Rothausen’s [74] multi-item scales (five items). The second and third parts focused on employees’ work engagement and satisfaction. Employee engagement was measured with five items using a 7-point scale based on those developed by Schaufeli and Bakker [75]. Employee satisfaction was measured using five items adapted from Spector [76] and Netemeyer et al. [77]. The fourth part focused on organizational commitment and was measured by five items developed by Meyer and Allen [78] and Mayer and Schoorman [48]. Finally, to confirm the respondents’ demographic characteristics, a questionnaire was constructed that included four items: gender, age for generational inferences, education level, and organizational departments.

3.3. Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences and the Analysis of Moment Structures were used as statistical methods for data processing. A frequency analysis was employed to understand the sample’s demographic characteristics, and confirmatory factor and reliability analyses were performed to verify the validity and reliability of the measurement variables [79]. This study’s hypotheses were tested using a structural equation model, and the moderating effect of generations was verified by a multigroup analysis to examine generational differences.

4. Results

4.1. Participants’ Demographic Information

The respondents’ demographics are presented in Table 1. In terms of gender distribution, 70.4% were male, and 29.6% were female, revealing that the proportion of men was significantly higher. In terms of generations segmented by age, Generation X, Generation Y, and Generation Z accounted for 29.6%, 47.7%, and 22.7%, respectively. Regarding education level, graduation from a four-year university accounted for the highest proportion (63.5%). In terms of departments, the FOH (front of the house) and BOH (back of the house) comprised 55.6% and 44.4%, respectively.

Table 1.

Profile of the sample (n = 277).

4.2. Measurement Model

Before testing the hypotheses, the validity and reliability of the measurement items were analyzed (see Table 2). According to the results of the confirmatory factor analysis (n = 20 measurement items), the items were factorized into four factors, and the model’s goodness of fit was also at an acceptable level (χ2 = 347.598; df = 164; χ2/df = 2.119; GFI = 0.975; NFI = 0.954; CFI = 0.975; RMSEA = 0.064). The maximum and minimum factor loading values were 0.945 and 0.891, respectively; thus, both values exceeded 0.8. The Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.962–0.971, and the CCR was 0.932–0.975. In addition, all the AVE values were above the reference value (0.5), which indicates that there was no problem with concentration validity and reliability. The squared value of the correlation coefficient for the constructs and the ASV and MSV values were also smaller than the AVE values, which demonstrated outstanding validity (see Table 3) [79,80].

Table 2.

Reliability and confirmatory factor analysis properties.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling

The results of testing the study’s hypotheses are shown in Table 4. According to the results of testing the research model’s goodness of fit, the goodness-of-fit indexes included χ2 = 420.124, χ2/df = 2.531, GFI = 0.873, NFI = 0.945, CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.961, and RMSEA = 0.074. Consequently, the structured model’s overall goodness of fit was considered adequate [80]. Because of the hypothesis testing, workplace flexibility had statistically significant effects on job engagement (β = 0.545; t = 9.871; p < 0.001) and satisfaction (β = 0.326; t = 5.159; p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported. In addition, work engagement (β = 0.315; t = 4.968; p < 0.001) had a statistically significant effect on employees’ satisfaction; thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported. Employees’ satisfaction (β = 0.497; t = 8.683; p < 0.001) had a statistically significant effect on commitment; therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Table 4.

Structural parameter estimates.

Table 5 presents the results of the analysis for testing the moderating role of employees’ generation (Hypothesis 5) in the relationship between workplace flexibility and work engagement. The moderating effect of generation was analyzed using the difference in freedom between the unconstrained and constrained models, and the positive influence of workplace flexibility on work engagement did not show a significant difference according to the employees’ generation. Accordingly, Hypothesis 5 was rejected. Although there was no significant difference, Generation Z showed the largest increase in employee engagement resulting from work flexibility. This result signifies that, compared to other generations, Generation Z places great importance on workplace flexibility.

Table 5.

Moderating effects on employee generation characteristics.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study examined the effects of workplace flexibility perceived by employees at deluxe hotels on their engagement, satisfaction, and commitment, and whether the effects of work flexibility on work engagement vary according to the employees’ generation (i.e., Generation X, Y, or Z). The results confirmed the positive effects of workplace flexibility on the engagement and satisfaction of deluxe hotel employees; this result supports previous studies [25,27,34,35]. This suggests that the more that employees are aware of workplace flexibility, the more engaged and satisfied they are with their organization and job, which subsequently contributes to organizational performance. Second, employees’ work engagement had a positive effect on their satisfaction, which confirms initial studies [39,44]. This means that when an organization’s members are actively focused on their jobs, their job satisfaction increases. Third, employee satisfaction had a positive impact on employees’ commitment, which is consistent with other studies [55]. This study suggests that if individuals are satisfied with their jobs, their levels of identification with and dedication to their organizations also increases. Fourth, the influence of workplace flexibility on engagement did not differ by generation.

The theoretical implications inferred from this study’s results are as follows. This study has academic significance as an initial study that investigated the organic causal relations between workplace flexibility perceived by employees at deluxe hotels and their engagement, satisfaction, and commitment. In doing so, this study lays a theoretical foundation for understanding the association between workplace flexibility at deluxe hotels and employees’ positive responses and behaviors. This outcome helps in understanding the process of workplace flexibility affecting employee engagement, satisfaction, and commitment. It also provides a theoretical opportunity to academically explore the appropriateness of the need to implement measures at the organizational level so employees can recognize positive workplace flexibility, and this provision is also likely to contribute to the sustainability of future research. In addition, although the moderating variable (i.e., generations) did not yield a statistically significant effect, this study is still significant in terms of resolving some inadequate areas not covered in conventional studies by introducing a new moderating variable, thereby addressing the need to expand the theories of earlier studies that focused on simple causal relations. Moreover, this study may offer an opportunity for researchers and practitioners to gain more meaningful and deep insight into generational groups.

This study’s findings provide practical implications for workplace flexibility. This study suggests that deluxe hotels should create flexible policies and organizational climates to increase employees’ work engagement, satisfaction, and commitment. At the organizational level, they should aim to make employee schedules as flexible as possible and establish practical policies across hotels’ various occupational groups. For example, it is necessary to implement concrete policies, such as providing training for job sharing among two or more employees, empowering members to arrange flexible schedules, and opening channels for smooth communication. This is because providing greater autonomy and flexibility to employees is predicted to ultimately have a positive impact on organizational performance by reducing the events of embarrassment caused by stress, boredom, fatigue, or work–life conflict [81,82]. All policies implemented at the macrolevel should be based on top management’s volition and approval. Organizational flexibility should also be visible and consistent, and top management needs to show its intention for workplace flexibility via various communication channels, which should be preceded by establishing norms associated with the organization’s culture and flexibility. Although no significant moderating effect was observed in this study, among the reviewed generations, workplace flexibility had the highest influence on engagement in Generation Z. This means that, compared to other generations, Generation Z places great value on workplace flexibility. Notably, Generation Z employees prefer an active and strategic organizational environment and a flexible environment. In particular, as the proportion of Generation Z is gradually increasing in the human supply of deluxe hotels in South Korea, these results suggest meaningful implications. Therefore, considering the increased unemployment due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic depression since this crisis, the hospitality industry needs to appeal particularly to Generation X through the values that are most shared with Generation Z. Based on this study’s results, the challenge that companies face is not simply to passively manage intergenerational conflicts caused by generational diversity but to harness them as opportunities and long-term corporate gains. This study implies that this task should be accompanied by an understanding of the different generations and the resulting differentiated policies based on practices and policies consistent with human values.

This study has some limitations that help in suggesting future research directions in a meaningful way. This study’s sample included employees of deluxe hotels in Seoul, and this limited demographic characteristic makes it difficult to generalize the research results. Future research should investigate hotel employees in other environments. In addition, this study’s measurement items were measured in the form of self-reporting, and thus, the respondents could answer according to their subjective opinions and what they considered desirable. Therefore, future research should require evaluations using more objective measurement tools. Certainly, the current measurement tool has been verified through many previous studies, but it is still impossible to detect or eliminate all response biases. It is also impossible to chronologically apply and understand this study’s findings because this research was conducted as a cross-sectional study. It is desirable to conduct future research as a comparative study on cultural dimensions based on longitudinal research. Finally, although this present study was limited to a single moderating variable of generations, it will be necessary for future research to utilize various moderating variables that can be influenced by workplace flexibility.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work. All the authors contributed to the conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing of the original draft, and review and editing. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ozturk, A.; Karatepe, O.M.; Okumus, F. The effect of servant leadership on hotel employees’ behavioral consequences: Work engagement versus job satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambler, K.; Godlonton, S.; Recalde, M.P. Fellow the leader? A field experiment on social influence. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2021, 188, 1280–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, A.L.; Civian, J.T.; Shannon, L.L.; Jeffrey, H.E.; Brennan, R.T. The relationship of perceived flexibility, supportive work–life policies, and use of formal flexible arrangements and occasional flexibility to employee engagement and expected retention. Community Work Fam. 2008, 11, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Magnini, V.P.; Kim, B.P. Employee satisfaction with schedule flexibility: Psychological antecedents and consequences within the workplace. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, H.E.; Jacob, J.I.; Shannon, L.L.; Brennan, R.T.; Blanchard, V.L.; Martinengo, G. Exploring the relationship of workplace flexibility, gender, and life stage to family-to-work conflict, and stress and burnout. Community Work Fam. 2008, 11, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.; Blomme, R.J. Forget about ‘the ideal worker’: A theoretical contribution to the debate on flexible workplace designs, work/life conflict, and opportunities for gender equality. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglalang, D.D.; Sorensen, G.; Hopcia, K.; Hashimoto, D.M.; Katigbak, C.; Pandey, S.; Takeuchi, D.; Sabbath, E.L. Job and family demands and burnout among healthcare workers: The moderating role of workplace flexibility. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossek, E.E.; Pichler, S.; Bodner, T.; Hammer, L.B. Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Staines, G.; Pleck, J. Work schedule flexibility and family life. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 7, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, M.; Kok, R.A.W. Workplace flexibility and new product development performance: The role of telework and flexible work schedules. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.; Kuron, L. Generational differences in the workplace: A review of the evidence and directions for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, S139–S157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J.; Hawkins, A.J.; Ferris, M.; Weitzman, M. Finding an extra day a week: The positive influence of perceived job flexibility on work and family life balance. Fam. Relat. 2001, 50, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, D.; Todnem, B.R.; Hutchings, K. Towards a model of human resource solutions for achieving intergenerational interactions in organisations. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2007, 31, 592–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Garriety, S. The art of flexibility: Bridging five generations in the workforce. Strategic HR Rev. 2020, 19, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdiyakorn, M.; Golubovskaya, M.; Solnet, D. Understanding generation Z through collective consciousness: Impacts for hospitality work and employment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capnary, M.C.; Rachmawati, R.; Agung, I. The influence of flexibility of work to loyalty and employee satisfaction mediated by work life balance to employees with millennial generation background in Indonesia startup companies. Verslas Teor. Prakt. 2018, 19, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Montes, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Han, H.; Law, R. Employee responsibility and basic human values in the hospitality sector. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 62, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Maier, T.A.; Chi, C.G. Generational differences: An examination of work values and generational gaps in the hospitality workforce. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Gursoy, D. Generation effects on work engagement among US hotel employees. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 31, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, M.; Solmaz, B. The changing face of the employees: Generation Z and their perceptions of work. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielova, K.; Buchko, A.A. Here comes generation Z: Millennials as managers. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Neveu, J.P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Edu. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayman, J.R. Flexible work arrangements: Exploring the linkages between perceived usability of flexible work schedules and work/life balance. Community Work Fam. 2009, 12, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B.; Hetland, J.; Keulemans, L. Do new ways of working foster work engagement? Psicothema 2012, 24, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Timms, C.; Brough, P.; O’Driscoll, M.; Kalliath, T.; Siu, O.L.; Sit, C.; Lo, D. Flexibility work arrangement, work engagement turnover intent and psychological health. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 53, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugargol, J.D.; Patrick, H.A. The relationship of workplace flexibility to employee engagement among information technology employees in India. South Asian J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 5, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porter, L.W. Job Attitudes in Management: Part I. J. Appl. Psychol. 1962, 46, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betty, R.W.; Schnier, C.E. Personnel Adminstration: An Experimental Skill Building Approach, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Burud, S.; Tumolo, M. Leveraging the New Human Capital: Adaptive Strategies, Results Achieved, and Stories of Transformation; Davies-Black Publishing: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. For better or for worse? An analysis of how flexible working practices influence employees’ perceptions of job quality. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Origo, F.; Pagani, L. Workplace flexibility and job satisfaction: Some evidence from Europe. Int. J. Manpow. 2008, 29, 539–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.D.; Poelmans, S.A.; Allen, T.D.; Spector, P.E.; Lapierre, L.M.; Cooper, C.L.; Lu, L. Flexible work arrangements availability and their relationship with work-to-family conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: A comparison of three country clusters. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 61, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. The effect mechanism of work flexibility on employee job satisfaction. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1053, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirotti, P.; Raguseo, E.; Gastaldi, L. Designing flexibility work practice for job satisfaction: The relation between job characteristics and work disaggregation in different types of work arrangements. New Technol. Work Employ. 2019, 34, 116–138. [Google Scholar]

- Davidescu, A.A.; Apostu, S.A.; Paul, A.; Casuneanu, I. Work flexibility, job satisfaction, and job performance among Romanian employees—Implications for sustainable human resource management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, T.K.; Pana-Cryan, R.P. Work flexibility and work-related well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Karanika-Murray, M. Contextualising over-engagement in work: Towards a more global understanding of workaholism as an addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2012, 1, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeh, C.M. Tourism involvement, work engagement and job satisfaction among frontline hotel employees. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 214–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayton, B.A.; Yalabik, Z.Y. Work engagement, psychological contract breach and job satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2382–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, L.; Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Neale, N.R. Work engagement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: A comparison between supervisors and line-level employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 737–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; Almeida, H. Work engagement, social support, and job satisfaction in Portuguese nursing staff: A winning combination. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 36, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, K.; Dar, I.A.; Mishra, M. Job satisfaction and work engagement: A study using private sector bank managers. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2018, 20, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rayton, B.; Yalabik, Z.Y.; Rapti, A. Fit perceptions, work engagement, satisfaction and commitment. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huang, P.; Yan, X.; Luo, Z. Psychological empowerment and work engagement as mediating roles between trait emotional intelligence and job satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Schoorman, F.D. Predicting participation and production outcomes through a two-dimensional model of organizational commitment. Acad. Manag. 1992, 35, 671–684. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, M.A.; Nisa, I. The influence of leadership and work attitudes toward job satisfaction and performance of employee. Int. J. Manag. Stud. Res. 2014, 2, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Valaei, N.; Rezaei, S. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: An empirical investigation among ICT-SMEs. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 1663–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ok, C. Hotel employee work engagement and its consequences. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 133–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliyana, A.; Maarif, S.; Muzakki. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment effect in the transformational leadership towards employee performance. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, E.T. Mediation effects of job satisfaction and work engagement on the relationship between organizational embeddedness and affective commitment among frontline employee of star-rated hotels in Accra. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, K. Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge; Routledge & Kegan Pau: London, UK, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, H.; Wang, S.; Fu, X. Meeting career expectation: Can it enhance job satisfaction of generation Y? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyoun, K.; Chen, H.; Ayoun, B.; Khliefat, A. The relationship between purpose of performance appraisal and psychological contract: Generational differences as a moderator. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.; Pitt, M.; Price, S. Understanding the impact of generational issues in the workplace. Facilities 2012, 30, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.A.; Thomas, N.J.; Bosselman, R.H. Are they leaving or staying: A qualitative analysis of turnover issues for generation Y hospitality employees with a hospitality education. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, I.A.; Wan, Y.K.P.; Gao, J.H. How to attract and retain generation Y employees? an exploration of career choice and the meaning of work. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, W.D.; Kang, S.; Huh, C.; Lee, M.J. What factors influence generation Y’s employee retention in the hospitality industry? An internal marketing approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. The 2017 Deloitte Millennial Survey: Apprehensive Stability and Opportunities in an Uncertain World. 2017. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/about-deloitte/deloitte-au-about-millennial-survey-2017-030217pdf (accessed on 14 September 2017).

- Solnet, D.; Baum, T.; Robinson, R.; Lockstone-Binney, L. What about the workers? Roles and skills for employees in hotels of the future. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelcase. Generations at Work: A War of Talents: Innovating to Integrate an Emerging Generation into the Workplace. 2009. Available online: www.steelcase.com (accessed on 1 January 2009).

- Pitt-Catsouphes, M.; Matz-Costa, C. The multi-generational workforce: Workplace flexibility and engagement. Community Work Fam. 2008, 11, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Knutson, B.J.; Choi, L. The effects of employee voice and delight on job satisfaction and behaviors: Comparison between employee generations. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Yoon, H.H. COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schawbel, D. Meet the Next Wave of Workers Who Are Taking over Your Office; CNBC: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, E.; Lee, C. A workforce to be reckoned with: The emerging pivotal generation Z hospitality workforce. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Okumus, F. Avoiding the hospitality workforce bubble: Strategies to attract and retain generation Z talent in the hospitality workforce. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, L.T.; Ganster, D.C. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthausen, T. Job satisfaction and the parent worker: The role of flexibility and rewards. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 44, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spector, P.E. Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: Development of the job satisfaction survey. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1985, 13, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McKee, D.O.; McMurrian, R. An investigation into the antecedents of organizational citizenship behaviors in a personal selling context. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N. Commitment to organizational and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Anderson, J.C. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1998, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, C.; Elias, S. Flex-time as a moderator of the job stress-work motivation relationship: A three nation investigation. Pers. Rew. 2010, 39, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J.; Erickson, J.J.; Holmes, E.K.; Ferris, M. Workplace flexibility, work hours, and work-life conflict: Finding an extra day or two. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).