Can Leaders’ Humility Enhance Project Management Effectiveness? Interactive Effect of Top Management Support

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Humble Leadership

3. Top Management Support

4. Employee Creativity

5. Project Management Effectiveness

6. Humble Leadership and Project Management Effectiveness

7. The Mediating Role of Employee Creativity

8. The Moderating Role of Top Management Support

9. Methodology

Sampling and Research Tool

10. Measures

11. Data Analysis

12. Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE)

13. Measurement Model

14. Structural Model Testing

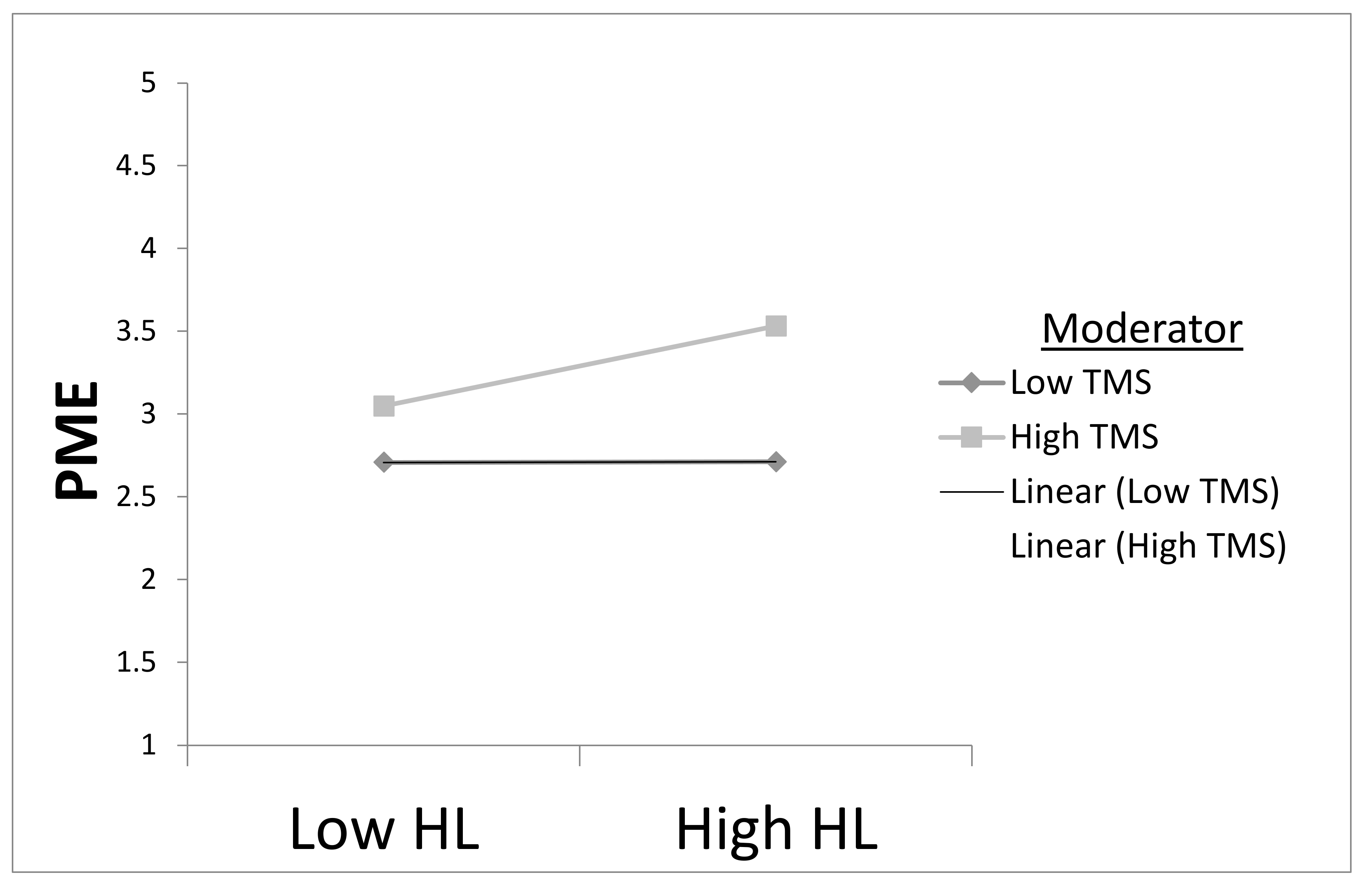

15. Moderated Mediation

16. Discussion

17. Practical Implications

18. Limitations and Future Research Directions

19. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tabassi, A.A.; Roufechaei, K.M.; Ramli, M.; Bakar, A.H.; Ismail, R.; Pakir, A.H. Leadership competences of sustainable construction project managers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floris, M.; Cuganesan, S. Project leaders in transition: Manifestations of cognitive and emotional capacity. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasapoğlu, E. Leadership styles in architectural design offices in Turkey. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 140, 04013047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, H. Essentials of Management; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Vaagaasar, A.L.; Müller, R.; Wang, L.; Zhu, F. Empowerment: The key to horizontal leadership in projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 992–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Zhang, L.; Shah Syed, J.; Khan, S.; Shah Adnan, M. Impact of humble leadership on project success: The mediating role of psychological empowerment and innovative work behavior. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Li, Z.; Haider, M.; Khan, S.; Din, Q.M.U. Does humility of project manager affect project success? Confirmation of moderated mediation mechanism. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/MRR-10-2020-0640/full/html (accessed on 16 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Zhou, J. When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to creative behavior: An interactional approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallén, F.; Domínguez-Escrig, E.; Lapiedra, R.; Chiva, R. Does leader humility matter? Effects on altruism and innovation. Manag. Decis. 2019, 58, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wu, G.; Xie, H.; Li, H. Leadership, organizational culture, and innovative behavior in construction projects: The perspective of behavior-value congruence. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 12, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.H.; Bahar, T. Factors influencing project management effectiveness in the Malaysian local councils. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 12, 1146–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, A. Top management support in multiple-project environments: An in-practice view. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Li, Z.; Khan, S.; Shah Syed, J.; Ullah, R. Linking humble leadership and project success: The moderating role of top management support with mediation of team-building. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 14, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Z.; Lin, C.; Luo, Z. Humble leadership and innovative behaviour among Chinese nurses: The mediating role of work engagement. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhber, M.; Khairuzzaman, W.; Vakilbashi, A. Leadership and innovation: The moderator role of organization support for innovative behaviors. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ou, A.Y.; Tsui, A.S.; Kinicki, A.J.; Waldman, D.A.; Xiao, Z.; Song, L.J. Humble chief executive officers’ connections to top management team integration and middle managers’ responses. Adm. Sci. Q. 2014, 59, 34–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórska, M.; Pichlak, M. Analysis of project managers’ leadership competencies: Project success relation: What are the competencies of polish project leaders? Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Yu, E.; Chu, X.; Li, Y.; Amin, K. Humble Leadership Affects Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Sequential Mediating Effect of Strengths Use and Job Crafting. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, A.Y.; Seo, J.; Choi, D.; Hom, P.W. When Can Humble Top Executives Retain Middle Managers? The Moderating Role of Top Management Team Faultlines. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 60, 1915–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, P.; Zhang, D.Z. Can leader humility enhance employee wellbeing? The mediating role of employee humility. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Chen, C.; Yam, K.C.; Huang, M.; Ju, D. The double-edged sword of leader humility: Investigating when and why leader humility promotes versus inhibits subordinate deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, K.N.; Diab, D.L. Humble Leadership: Implications for Psychological Safety and Follower Engagement. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2016, 10, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonçalves, L. The relation between leader’s humility and team creativity. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 25, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, N.; Zafar, M.S.; Bashir, S. The combined effects of managerial control, resource commitment, and top management support on the successful delivery of information systems projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Mohamad, N.A.B.; Ahmad, M.S. Effect of multidimensional top management support on project success: An empirical investigation. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, A. How do top managers support strategic information system projects and why do they sometimes withhold this support? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, R.; Sudong, Y. Critical success factors for renewable energy projects; empirical evidence from Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.-C.; Chen, J.-Y.; Wang, M.-J.; Chen, C.-Y. The Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Employees’ Innovative Behaviors: The Mediation of Psychological Capital. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheung, S.Y.; Huang, E.G.; Chang, S.; Wei, L. Does being mindful make people more creative at work? The role of creative process engagement and perceived leader humility. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2020, 159, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mishra, P.; Bhatnagar, J.; Gupta, R.; Wadsworth, S.M. How work–Family enrichment influence innovative work behavior: Role of psychological capital and supervisory support. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, A.E. Team wisdom in software development projects and its impact on project performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanakul, P. How to Achieve Effectiveness in Project Portfolio Management. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 1–13. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8989787 (accessed on 16 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Unger, B.N.; Kock, A.; Gemünden, H.G.; Jonas, D. Enforcing strategic fit of project portfolios by project termination: An empirical study on senior management involvement. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2012, 30, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Li, Z.; Durrani, D.K.; Shah, A.M.; Khuram, W. Goal clarity as a link between humble leadership and project success: The interactive effects of organizational culture. Balt. J. Manag. 2021, 16, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Cunha, M.P.e.; Simpson, A.V. The perceived impact of leaders’ humility on team effectiveness: An empirical study. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, R.; Turner, R. Leadership competency profiles of successful project managers. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brière, S.; Proulx, D.; Flores, O.N.; Laporte, M. Competencies of project managers in international NGOs: Perceptions of practitioners. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Chen, Z.X.; Herman, H.; Wei, W.; Ma, C. Why and when employees like to speak up more under humble leaders? The roles of personal sense of power and power distance. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cserháti, G.; Szabó, L. The relationship between success criteria and success factors in organisational event projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; Qian, S. Can leader “humility” spark employee “proactivity”? The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammons, D.N.; Roenigk, D.J. Exploring Devolved Decision Authority in Performance Management Regimes: The Relevance of Perceived and Actual Decision Authority as Elements of Performance Management Success. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2020, 43, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argandona, A. Humility in management. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.; Dionisi, A.M.; Barling, J.; Akers, A.; Robertson, J.; Lys, R.; Wylie, J.; Dupré, K. The depleted leader: The influence of leaders’ diminished psychological resources on leadership behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wu, Y.J. How humble leadership fosters employee innovation behavior: A two-way perspective on the leader-employee interaction. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Y. Humble leadership, psychological safety, knowledge sharing and follower creativity: A cross-level investigation. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Owens, B.P.; Hekman, D.R. How does leader humility influence team performance? Exploring the mechanisms of contagion and collective promotion focus. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1088–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. The Role of Trust in Organizational Settings. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Nehles, A.C.; Veenendaal, A.A.R. Perceptions of HR practices and innovative work behavior: The moderating effect of an innovative climate. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 2661–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, S.J.; Coote, L.V. Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A test of Schein’s model. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černe, M.; Hernaus, T.; Dysvik, A.; Škerlavaj, M. The role of multilevel synergistic interplay among team mastery climate, knowledge hiding, and job characteristics in stimulating innovative work behavior. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, P.F.; Bell, J.C.H. Effects of Team Building and Goal Setting on Productivity: A Field Experiment. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 29, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley John, H.; Hebert Frederic, J. The effect of personality type on team performance. J. Manag. Dev. 1997, 16, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montani, F.; Vandenberghe, C.; Khedhaouria, A.; Courcy, F. Examining the inverted U-shaped relationship between workload and innovative work behavior: The role of work engagement and mindfulness. Hum. Relat. 2020, 73, 59–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobni, C.B.; Klassen, M. The decade of innovation: From benchmarking to execution. J. Bus. Strat. 2021, 42, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Cao, G.; Edwards, J.S. Understanding the impact of business analytics on innovation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 281, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, F.; Woodman, R.W. Innovative behavior in the workplace: The role of performance and image outcome expectations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.-C.; Chen, C.-Y. Exploring the team dynamic learning process in software process tailoring performance: A theoretical perspective. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 33, 502–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kor, Y.Y. Experience-based top management team competence and sustained growth. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehoff, B.P.; Enz, C.A.; Grover, R.A. The impact of top-management actions on employee attitudes and perceptions. Group Organ. Stud. 1990, 15, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavan, T.N. A Strategic Perspective on Human Resource Development. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2007, 9, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schultz, C.; Graw, J.; Salomo, S.; Kock, A. How Project Management and Top Management Involvement Affect the Innovativeness of Professional Service Organizations—An Empirical Study on Hospitals. Proj. Manag. J. 2019, 50, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. Oxf. Handb. Stress Health Coping 2011, 127–147. Available online: https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195375343.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195375343-e-007 (accessed on 16 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Santos-Vijande, M.L.; López-Sánchez, J.Á.; Pascual-Fernandez, P. Co-creation with clients of hotel services: The moderating role of top management support. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 301–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwikael, O. Top management involvement in project management. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2008, 1, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuester, S.; Schuhmacher, M.C.; Gast, B.; Worgul, A. Sectoral Heterogeneity in New Service Development: An Exploratory Study of Service Types and Success Factors. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, A.N.; van Knippenberg, D.; Schippers, M.; Stam, D. Transformational and transactional leadership and innovative behavior: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, C. The cumulative power of incremental innovation and the role of project sequence management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenkov, D.S.; Manev, I.M. Top Management Leadership and Influence on Innovation: The Role of Sociocultural Context. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stuckenbruck, L. Who determines project success. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual Seminar/Symposium, Montréal, CA, Canada, 20–25 September 1986; pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Raziq, M.M.; Borini, F.M.; Malik, O.F.; Ahmad, M.; Shabaz, M. Leadership styles, goal clarity, and project success: Evidence from project-based organizations in Pakistan. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creasy, T.; Anantatmula, V.S. From Every Direction—How Personality Traits and Dimensions of Project Managers Can Conceptually Affect Project Success. Proj. Manag. J. 2013, 44, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creasy, T.; Carnes, A. The effects of workplace bullying on team learning, innovation and project success as mediated through virtual and traditional team dynamics. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shah Syed, J.; Shah Syed Asad, A.; Ullah, R.; Shah Adnan, M. Deviance due to fear of victimization: “emotional intelligence” a game-changer. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2020, 31, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, B.P.; Johnson, M.D.; Mitchell, T.R. Expressed humility in organizations: Implications for performance, teams, and leadership. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 1517–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Islam, Z.; Doshi, J.A.; Mahtab, H.; Ahmad, Z.A. Team learning, top management support and new product development success. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2009, 2, 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Testing structural equation models. Sage Focus Ed. 1993, 154, 294. [Google Scholar]

- Naseer, S.; Bouckenooghe, D.; Syed, F.; Khan, A.K.; Qazi, S. The malevolent side of organizational identification: Unraveling the impact of psychological entitlement and manipulative personality on unethical work behaviors. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. “Issues in the application of covariance structure analysis”: A further comment. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 9, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S.P. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anjum, M.A.; Liang, D.; Durrani, D.K.; Ahmed, A. Workplace ostracism and discretionary work effort: A conditional process analysis. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 1–18. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332094547_Workplace_ostracism_and_discretionary_work_effort_A_conditional_process_analysis (accessed on 16 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.J.; Zhang, L.; Khan, S.; Shah, S.A.A.; Durrani, D.K.; Ali, L.; Das, B. Terrorism vulnerability: Organizations’ ambiguous expectations and employees’ conflicting priorities. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2018, 26, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, P.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J.; Xue, Z. Helping neighbors and enhancing yourself: A spillover effect of helping neighbors on work-family conflict and thriving at work. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 1–12. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2020-45567-001 (accessed on 16 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Li, X. Resilience, leadership and work engagement: The mediating role of positive affect. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidmar, M. Enablers, Equippers, Shapers and Movers: A typology of innovation intermediaries’ interventions and the development of an emergent innovation system. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 179, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todt, G.; Weiss, M.; Hoegl, M. Mitigating Negative Side Effects of Innovation Project Terminations: The Role of Resilience and Social Support. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2018, 35, 518–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; Potočnik, K.; Zhou, J. Innovation and Creativity in Organizations: A State-of-the-Science Review, Prospective Commentary, and Guiding Framework. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Cheng, B.; Zhong, J. Is a mindful worker more attentive? the role of moral self-efficacy and moral disengagement. Ethics Behav. 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumusluoğlu, L.; Ilsev, A. Transformational Leadership and Organizational Innovation: The Roles of Internal and External Support for Innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2009, 26, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Berry, J.W. The Necessity of Others is The Mother of Invention: Intrinsic and Prosocial Motivations, Perspective Taking, and Creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yidong, T.; Xinxin, L. How Ethical Leadership Influence Employees’ Innovative Work Behavior: A Perspective of Intrinsic Motivation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat Ar, I.; Baki, B. Antecedents and performance impacts of product versus process innovation: Empirical evidence from SMEs located in Turkish science and technology parks. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2011, 14, 172–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermano, V.; Martín-Cruz, N. The role of top management involvement in firms performing projects: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3447–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberda, H.W.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Heij, C.V. Management Innovation: Management as Fertile Ground for Innovation. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2013, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Schatzel, E.A.; Moneta, G.B.; Kramer, S.J. Leader behaviors and the work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.-D.; Jia, W.-T. When and Why Leaders’ Helping Behavior Promotes Employees’ Thriving: Exploring the Role of Voice Behavior and Perceived Leader’s Role Overload. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidman, A.C.; Cheng, J.T.; Tracy, J.L. The psychological structure of humility. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 114, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 543–576. [Google Scholar]

| Measures | Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 210 | 63.2 |

| Female | 122 | 36.8 | |

| Age (years) | 20–30 | 81 | 24.9 |

| 31–40 | 92 | 27.6 | |

| 41–50 | 86 | 25.5 | |

| Above 51 | 73 | 22.0 | |

| Education | Bachelors | 237 | 71.5 |

| Master | 65 | 19.0 | |

| Diploma | 30 | 9.5 | |

| Work Experience | Less than 5year | 25 | 7.4 |

| 5–10 years | 100 | 30.6 | |

| 11–15 years | 131 | 39.5 | |

| 16 years and above | 76 | 22.6 |

| CR | Mean | SD | AVE | EC | PME | HL | TMS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | 0.91 | 3.5 | 0.85 | 0.55 | 0.74 | |||

| PME | 0.94 | 3.8 | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.27 ** | 0.78 | ||

| HL | 0.93 | 3.6 | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.19 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.761 | |

| TMS | 0.89 | 3.5 | 0.77 | 0.58 | 0.17 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.063 | 0.764 |

| Models | χ2 | χ2/df | NFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized 4 factor Model (M0) | 779.7 | 1.49 | 0.896 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.038 |

| Two Factors Model (F1 = HL + PME, F2 = EC + TMS) (M1) | 3475.2 | 6.6 | 0.537 | 0.547 | 0.576 | 0.129 |

| Two Factors Model (F1 = HL + EC, F2 = TMS + PME) (M2) | 3299.4 | 6.27 | 0.561 | 0.574 | 0.601 | 0.125 |

| Three Factors Model (F1 = HL + EC, F2 = TMS, F3 = PME) (M3) | 2311.8 | 4.412 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.101 |

| Three Factors Model (F1 = HL + PME, F2 = EC, F3 = TMS) (M4) | 2483 | 4.73 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.105 |

| Single Factor Model (M5) | 4904.9 | 9.30 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.157 |

| Path | Coefficient | SE | t-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | |||||

| Age | → | Project Management Effectiveness | 0.018 | 0.04 | 0.32 |

| Education | → | Project Management Effectiveness | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.16 |

| Work Experience | → | Project Management Effectiveness | −0.12 | 0.05 | −2.50 |

| Gender | → | Project Management Effectiveness | 0.16 | 0.08 | 1.84 |

| Main effects | |||||

| Humble Leadership | → | Project Management Effectiveness | 0.15 | 0.05 | 2.70 |

| Employee Creativity | → | Project Management Effectiveness | 0.21 | 0.05 | 3.25 |

| Humble Leadership | → | Employee Creativity | 0.18 | 0.05 | 3.26 |

| HL_X_TMS | → | Project Management Effectiveness | 0.17 | 0.04 | 2.89 |

| HL_X_TMS | → | Employee Creativity | 0.11 | 0.04 | 2.59 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zada, M.; Begum, A.; Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A. Can Leaders’ Humility Enhance Project Management Effectiveness? Interactive Effect of Top Management Support. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179526

Ali M, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Zada M, Begum A, Han H, Ariza-Montes A, Vega-Muñoz A. Can Leaders’ Humility Enhance Project Management Effectiveness? Interactive Effect of Top Management Support. Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179526

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Mudassar, Li Zhang, Zhenduo Zhang, Muhammad Zada, Abida Begum, Heesup Han, Antonio Ariza-Montes, and Alejandro Vega-Muñoz. 2021. "Can Leaders’ Humility Enhance Project Management Effectiveness? Interactive Effect of Top Management Support" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179526

APA StyleAli, M., Zhang, L., Zhang, Z., Zada, M., Begum, A., Han, H., Ariza-Montes, A., & Vega-Muñoz, A. (2021). Can Leaders’ Humility Enhance Project Management Effectiveness? Interactive Effect of Top Management Support. Sustainability, 13(17), 9526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179526