Actions Speak Louder than Words: Investigating the Interplay between Descriptive and Injunctive Norms to Promote Alternative Fuel Vehicles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

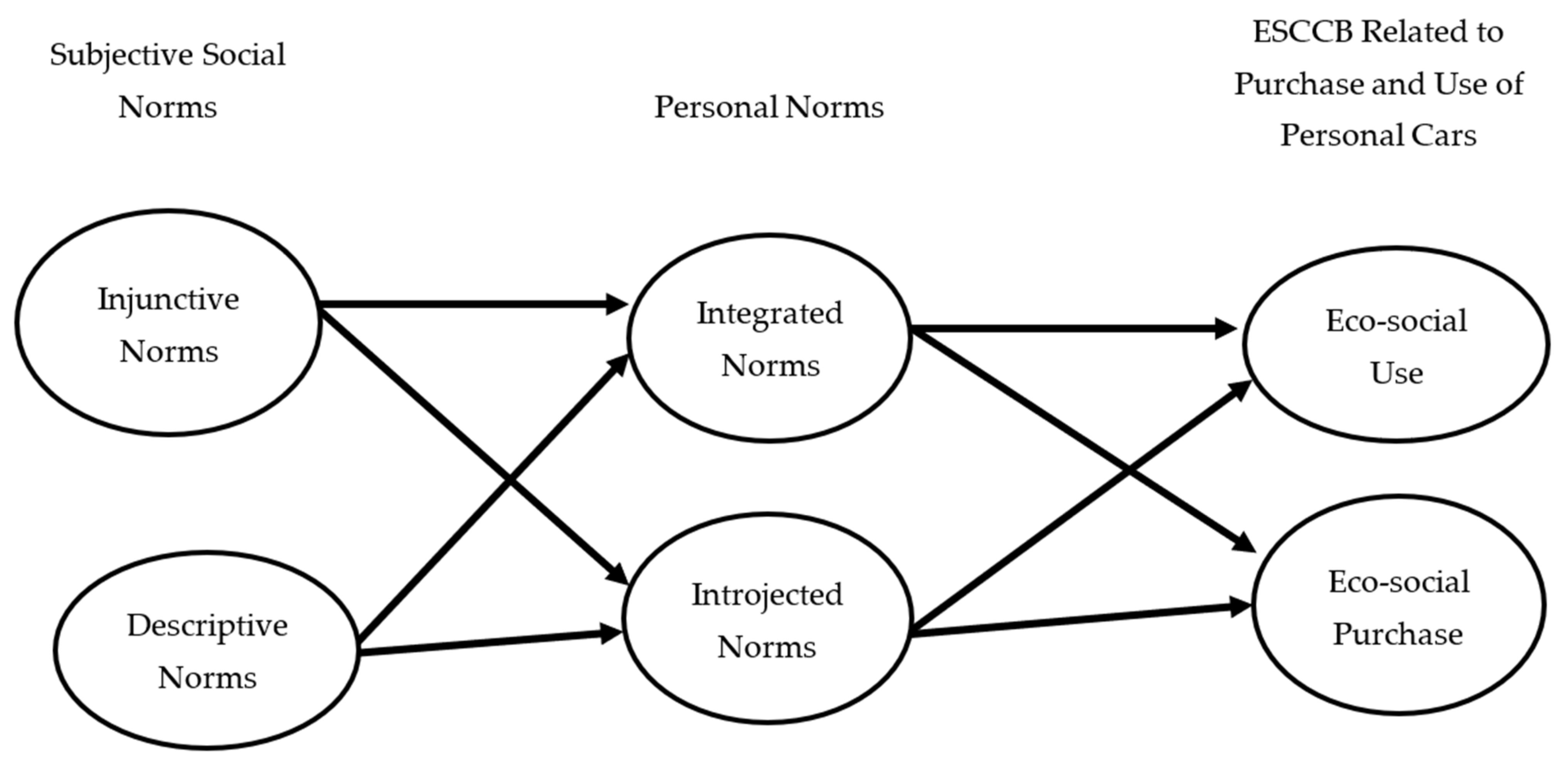

2. Background and Research Framework

2.1. Subjective Norms: Descriptive and Injunctive Norms

2.2. Personal Norms: Introjected and Integrated Norms

2.3. Mediating Role of Personal Norms

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Sample Size

3.3. Measurement Instrument

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Profile

4.2. Measurement Model Validation

4.3. Statistical Analysis

4.4. Structural Model Evaluation

4.5. Robustness Checks

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Hypotheses | Statement | Result |

|---|---|---|

| H1a | Descriptive norms are positively associated with eco-social purchase of personal cars | Supported |

| H1b | Descriptive norms are positively associated with eco-social use of personal cars | Supported |

| H2a | Injunctive norms are positively associated with eco-social purchase of personal cars | Not supported |

| H2b | Injunctive norms are positively associated with eco-social use of personal cars | Supported |

| H3a | Integrated norms are positively associated with eco-social purchase of personal cars | Supported |

| H3b | Integrated norms are positively associated with eco-social use of personal cars | Supported |

| H4a | Introjected norms are positively associated with eco-social purchase of personal cars | Supported |

| H4b | Introjected norms are positively associated with eco-social use of personal cars | Not supported |

| H5a | Injunctive norms are associated with integrated norms | Supported |

| H5b | Injunctive norms are associated with introjected norms | Supported |

| H6a | Descriptive norms are associated with integrated norms | Supported |

| H6b | Descriptive norms are associated with introjected norms | Supported |

| H7a | Integrated norms mediate the relationship of injunctive norms with eco-social purchase of personal cars | Supported |

| H7b | Integrated norms mediate the relationship of injunctive norms with eco-social use of personal cars | Supported |

| H8a | Introjected norms mediate the relationship of injunctive norms with eco-social purchase of personal cars | Supported |

| H8b | Introjected norms mediate the relationship of injunctive norms with eco-social use of personal cars | Not supported |

| H9a | Integrated norms mediate the relationship of descriptive norms with eco-social purchase of personal cars | Not Supported |

| H9b | Integrated norms mediate the relationship of descriptive norms with eco-social use of personal cars | Supported |

| H10a | Introjected norms mediate the relationship of descriptive norms with eco-social purchase of personal cars | Not supported |

| H10b | Introjected norms mediate the relationship of descriptive norms with eco-social use of personal cars | Not supported |

Appendix B

| Constructs | Items | Description of Items |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Injunctive Norms | SbInNr1 | People who are important to me will support me when I drive an environment-friendly car |

| SbInNr2 | People who are important to me try to convince me to drive an environment-friendly car | |

| SbInNr3 | Most people who are important to me think I should buy an environment-friendly car | |

| SbInNr5 | People whose opinions I value would prefer me to do carpooling whenever possible for commuting | |

| SbInNr6 | Many of the people that are important to me insinuated that I should consider environmental protection while buying a car | |

| 2. Descriptive Norms | SbDNr1 | Most of the people that are important to me own environment-friendly cars |

| SbDNr2 | I believe that most of the people that are important to me are considering buying an environmentally friendly car | |

| SbDNr3 | Most of the people that are important to me do carpooling for commuting | |

| 3. Eco-social Purchase | ESCBPInt1 | I would buy an alternative fuel vehicle even if its quality is lower than a conventional car |

| ESCBPInt2 | I would buy an alternative fuel vehicle even if its performance is lower than a conventional car | |

| ESCBPInt3 | I would buy an alternative fuel vehicle even if it has a less appealing design | |

| 4. Eco-social Conservation | ESCBCInt1 | I have selected a car with a high rear axle ration since that produces the least friction and saves energy |

| ESCBCInt2 | I avoid using wide thread tires since that causes road friction and consumes more fuel | |

| ESCBCInt3 | I consider using radial tires since that helps to preserve fuel resources | |

| 5. Eco-social Use | ESCBUInt1 | If I have multiple car choices available, given all other factors are the same, I will choose the one with better environmental performance |

| ESCBUInt2 | Knowing that excessive speed is inefficient, requiring more energy to stop the car, I consider observing speed limits | |

| ESCBUInt3 | Knowing that excessive speed is inefficient, requiring more energy to stop the car, I consider observing a steady pace | |

| 6. Integrated Norms | PersIntegNorm1 | I feel an obligation to choose an environment-friendly car instead of a traditional one |

| PersIntegNorm2 | I feel personally obliged to reduce the use of a personal car as much as possible | |

| PersIntegNorm3 | Regardless of what others do, I feel it is my moral obligation to use an environment-friendly car | |

| PersIntegNorm4 | Regardless of what others do, I feel it is my moral obligation to avoid using the car as much as possible for commuting | |

| PersIntegNorm7 | I feel it obligatory to bear the environment and nature in mind in my daily life behavior | |

| 7. Introjected Norms | PersIntroNorm3 | I sometimes have a bad conscience because I use my personal car excessively when I can avoid it |

| PersIntroNorm4 | I sometimes have a bad conscience that I own a powerful and spacious car | |

| PersIntroNorm5 | I would sometimes have a bad conscience if I owned a powerful and spacious car | |

| PersIntroNorm6 | I sometimes have a bad conscience that I am using my personal car when I can use public transport |

References

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vocino, A.; Polonsky, M.J. The influence of eco-label knowledge and trust on pro-environmental consumer behaviour in an emerging market. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 25, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.-C. Effects of green brand on green purchase intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, M.; Hargrove, W.L.; Tomaka, J.; Korc, M. Transportation Matters: A Health Impact Assessment in Rural New Mexico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adnan, N.; Nordin, S.M.; Amini, M.H.; Langove, N. What make consumer sign up to PHEVs? Predicting Malaysian consumer behavior in adoption of PHEVs. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 113, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y. Using the sustainable modified TAM and TPB to analyze the effects of perceived green value on loyalty to a public bike system. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 88, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.A.; Eagle, L.; Low, D. Market segmentation based on eco-socially conscious consumers’ behavioral intentions: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.A.; Eagle, L.; Low, D. Climate change behaviors related to purchase and use of personal cars: Development and validation of eco-socially conscious consumer behavior scale. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 59, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannberg, A.; Jansson, J.; Pettersson, T.; Brännlund, R.; Lindgren, U. Do tax incentives affect households׳ adoption of ‘green’ cars? A panel study of the Stockholm congestion tax. Energy Policy 2014, 74, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wadud, Z.; MacKenzie, D.; Leiby, P. Help or hindrance? The travel, energy and carbon impacts of highly automated vehicles. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 86, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chowdhury, M.; Salam, K.; Tay, R. Consumer preferences and policy implications for the green car market. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2016, 34, 810–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A.; de Haan, P.; Woersdorfer, J.S. Consumer support for environmental policies: An application to purchases of green cars. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2078–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, J.D.; Lee, S.H. Hybrid car purchase intentions: A cross-cultural analysis. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, H.; Tol, R.S.J. The impact of tax reform on new car purchases in Ireland. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7059–7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nayum, A.; Klöckner, C.A.; Prugsamatz, S. Influences of car type class and carbon dioxide emission levels on purchases of new cars: A retrospective analysis of car purchases in Norway. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 48, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobeth, S.; Kastner, I. Buying an electric car: A rational choice or a norm-directed behavior? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 73, 236–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiawan, P.F.; Schmöcker, J.-D.; Fujii, S. Effects of Peer Influence, Satisfaction and Regret on Car Purchase Desire. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 17, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saleem, M.A.; Eagle, L.; Low, D. Determinants of eco-socially conscious consumer behavior toward alternative fuel vehicles. J. Consum. Mark. 2021, 38, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N.; Haslam, S. Social identity theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Van Lange, P.A., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 379–398. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.W.; Hong, Y.-y.; Chiu, C.-y.; Liu, Z. Normology: Integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2015, 129, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J. Norms for environmentally responsible behaviour: An extended taxonomy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Cieciuch, J.; Vecchione, M.; Torres, C.; Dirilen-Gumus, O.; Butenko, T. Value tradeoffs propel and inhibit behavior: Validating the 19 refined values in four countries. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R. A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: A Theoretical Refinement and Reevaluation of the Role of Norms in Human Behavior. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Volume 24, pp. 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Arpita, K. Antecedents to green buying behaviour: A study on consumers in an emerging economy. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, E.-J.; Hur, W.-M. The Normative Social Influence on Eco-Friendly Consumer Behavior: The Moderating Effect of Environmental Marketing Claims. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2012, 30, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, K.; Ling, F.; Feng, Z.; Wang, K.; Shao, C. Why do drivers continue driving while fatigued? An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 98, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, K.; Grolleau, G.; Ibanez, L. Social Norms and Pro-environmental Behavior: A Review of the Evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, A.; Elliott, C.G.; Bang, F.; Roberts, K.C.; Thompson, W.; Prince, S.A. Population health measurement of social norms for sedentary behaviour: A systematic review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 47, 101631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, M.; Nilsson, A.; Schultz, W.P. A meta-analysis of field-experiments using social norms to promote pro-environmental behaviors. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 59, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, A.B.; Steg, L.; Gorsira, M. Values Versus Environmental Knowledge as Triggers of a Process of Activation of Personal Norms for Eco-Driving. Environ. Behav. 2017, 50, 1092–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jansson, J.; Pettersson, T.; Mannberg, A.; Brännlund, R.; Lindgren, U. Adoption of alternative fuel vehicles: Influence from neighbors, family and coworkers. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 54, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, N.; Karjaluoto, H. Environmental values and customer-perceived value in industrial supplier relationships. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuda Bakti, I.G.M.; Rakhmawati, T.; Sumaedi, S.; Widianti, T.; Yarmen, M.; Astrini, N.J. Public transport users’ WOM: An integration model of the theory of planned behavior, customer satisfaction theory, and personal norm theory. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 48, 3365–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A.; Ohms, S. The importance of personal norms for purchasing organic milk. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 1173–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, H.B.; Nordfjærn, T.; Jørgensen, S.H.; Rundmo, T. The value-belief-norm theory, personal norms and sustainable travel mode choice in urban areas. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Leonard, B., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation. In Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldo, R.; Castro, P. The outer influence inside us: Exploring the relation between social and personal norms. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 112, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.H.; Seock, Y.-K. The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lede, E.; Meleady, R.; Seger, C.R. Optimizing the influence of social norms interventions: Applying social identity insights to motivate residential water conservation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 62, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savani, K.; Wadhwa, M.; Uchida, Y.; Ding, Y.; Naidu, N.V.R. When norms loom larger than the self: Susceptibility of preference–Choice consistency to normative influence across cultures. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2015, 129, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzig, J.; Gruchmann, T. Consumer Preferences for Local Food: Testing an Extended Norm Taxonomy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saleemi, U. ‘Big Three’ Dominate Pakistan’s Car Market for Yet Another Year. Available online: https://www.pakwheels.com/blog/big-three-dominate-pakistans-car-market-yet-another-year/ (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Bickman, L.; Rog, D.J. The SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.; Khan, H.T.A.; Raeside, R.; White, D. Sampling. In Research Methods for Graduate Business and Social Science Students; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- LaRose, R.; Tsai, H.-y.S. Completion rates and non-response error in online surveys: Comparing sweepstakes and pre-paid cash incentives in studies of online behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 34, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.E.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Moons, I.; De Pelsmacker, P. An Extended Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict the Usage Intention of the Electric Car: A Multi-Group Comparison. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6212–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doran, R.; Larsen, S. The Relative Importance of Social and Personal Norms in Explaining Intentions to Choose Eco-Friendly Travel Options. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ADB. Policy Brief on Female Labor Force Participation in Pakistan. 2016. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/209661/female-labor-force-participation-pakistan.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- CIA. The World Factbook—Pakistan. 2020. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pk.html (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most From Your Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis: Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wismeijer, A.A.J. Dimensionality Analysis of the Thought Suppression Inventory: Combining EFA, MSA, and CFA. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2012, 34, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saleem, M.A.; Yaseen, A.; Wasaya, A. Drivers of customer loyalty and word of mouth intentions: Moderating role of interactional justice. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, R.; Cote, J.A.; Baumgartner, H. Multicollinearity and Measurement Error in Structural Equation Models: Implications for Theory Testing. Mark. Sci. 2004, 23, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benitez, J.; Henseler, J.; Castillo, A.; Schuberth, F. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Kwon, J. The role of trait and emotion in cruise customers’ impulsive buying behavior: An empirical study. J. Strateg. Mark. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, N.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.; Feistel, M.S.G. The link between customer satisfaction and loyalty: The moderating role of customer characteristics. J. Strateg. Mark. 2018, 26, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, A.E.; Jaramillo, F. Salesperson implementation of sales strategy and its impact on sales performance. J. Strateg. Mark. 2020, 28, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. How to Write Up and Report PLS Analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2015; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; I Moisescu, O.; Radomir, L. Structural model robustness checks in PLS-SEM. Tour. Econ. 2019, 26, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J.B. Tests for Specification Errors in Classical Linear Least-Squares Regression Analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1969, 31, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Mooi, E. A Concise Guide to Market Research: The Process, Data, and Methods Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, B.; Eva, N.; Fazlelahi, F.Z.; Newman, A.; Lee, A.; Obschonka, M. Addressing common method variance and endogeneity in vocational behavior research: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 121, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hair, J.F.; Proksch, D.; Sarstedt, M.; Pinkwart, A.; Ringle, C.M. Addressing Endogeneity in International Marketing Applications of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Gupta, S. Handling Endogenous Regressors by Joint Estimation Using Copulas. Mark. Sci. 2012, 31, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J. Consumer eco-innovation adoption: Assessing attitudinal factors and perceived product characteristics. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettie, R.; Burchell, K.; Barnham, C. Social normalisation: Using marketing to make green normal. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-T. Consumer characteristics and social influence factors on green purchasing intentions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Age | 19–26 | 436 | 63.6 |

| >26–33 | 128 | 18.7 | |

| >33–40 | 78 | 11.4 | |

| >40–47 | 6 | 0.9 | |

| >47–54 | 22 | 3.2 | |

| >54–61 | 12 | 1.7 | |

| >61 | 4 | 0.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 382 | 55.7 |

| Female | 304 | 44.3 | |

| Education | No formal education | 6 | 0.9 |

| Primary (year 5) | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Secondary school certificate (year 10) | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Higher secondary school certificate (year 12) | 33 | 4.8 | |

| Undergraduate (Year 16) | 172 | 25.1 | |

| Masters (year 18) | 230 | 33.5 | |

| MBBS or BDS | 186 | 27.1 | |

| DVM | 18 | 2.6 | |

| BE | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Others | 33 | 4.8 | |

| Income a | 45,000–55,000 | 269 | 39.2 |

| >55,000–65,000 | 65 | 9.5 | |

| >65,000–75,000 | 116 | 16.9 | |

| >75,000–85,000 | 47 | 6.9 | |

| >85,000–95,000 | 57 | 8.3 | |

| >95,000–105,000 | 50 | 7.3 | |

| >105,000 | 82 | 12.0 | |

| Location | City | 594 | 86.6 |

| Suburb | 27 | 3.9 | |

| Village | 65 | 9.5 | |

| Marital status | Single | 483 | 70.4 |

| Married | 186 | 27.1 | |

| Divorced | 14 | 2.0 | |

| Widowed | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Constructs | Dimension | Items | Standardized Loadings | AVE | α | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Social Norms | Injunctive Norms—Belief Strength | 0.700 | 0.785 | 0.875 | ||

| SN1 | 0.834 | - | - | - | ||

| SN2 | 0.869 | - | - | - | ||

| SN3 | 0.806 | - | - | - | ||

| Injunctive Norms—Motivation to Comply | 0.661 | 0.745 | 0.854 | |||

| MotCply1 | 0.795 | - | - | - | ||

| MotCmply2 | 0.832 | - | - | - | ||

| Motcmply3 | 0.811 | - | - | - | ||

| Descriptive Norms | 0.692 | 0.779 | 0.871 | |||

| DescNorm1 | 0.801 | - | - | - | ||

| DescNorm2 | 0.825 | - | - | - | ||

| DescNorm3 | 0.869 | - | - | - | ||

| Personal Norms | Introjected Norms | 0.618 | 0.796 | 0.866 | ||

| PersIntroNorm3 | 0.801 | - | - | - | ||

| PersIntroNorm4 | 0.859 | - | - | - | ||

| PersIntroNorm5 | 0.766 | - | - | - | ||

| PersIntroNorm6 | 0.712 | - | - | - | ||

| Integrated Norms | 0.596 | 0.830 | 0.880 | |||

| PersIntegNorm1 | 0.809 | - | - | - | ||

| PersIntegNorm2 | 0.801 | - | - | - | ||

| PersIntegNorm3 | 0.796 | - | - | - | ||

| PersIntegNorm4 | 0.715 | - | - | - | ||

| PersIntegNorm7 | 0.736 | - | - | - | ||

| ESCCB purchase and use of personal cars | Eco-social Use | 0.609 | 0.839 | 0.886 | ||

| ESCCBCInt1 | 0.795 | - | - | - | ||

| ESCCBCInt2 | 0.793 | - | - | - | ||

| ESCCBCInt3 | 0.831 | - | - | - | ||

| ESCCBUInt1 | 0.749 | - | - | - | ||

| ESCCBUInt2 | 0.729 | - | - | - | ||

| Eco-social Purchase | 0.754 | 0.837 | 0.902 | |||

| ESCCBPInt1 | 0.883 | - | - | - | ||

| ESCCBPInt2 | 0.842 | - | - | - | ||

| ESCCBPInt3 | 0.878 | - | - | - | ||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.910 | |||||

| Bartlett’s Test | 0.000 | |||||

| Total Variance Explained | 52.99% | |||||

| Constructs | VIF | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Injunctive Norms—Belief Strength | 1.599, 1.519 | 0.836 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| B. Injunctive Norms—Motivation to Comply | 1.514, 1.456 | (0.687) 0.530 ** | 0.813 | - | - | - | - | - |

| C. Descriptive Norms | 1.368, 1.291 | (0.554) 0.435 ** | (0.514) 0.392 ** | 0.832 | - | - | - | - |

| D. Introjected Norms | 1.535 | (0.355) 0.290 ** | (0.364) 0.289 ** | (0.328) 0.266 ** | 0.786 | - | - | - |

| E. Integrated Norms | 1.880 | (0.547) 0.445 ** | (0.518) 0.415 ** | (0.510) 0.415 ** | (0.706) 0.588 ** | 0.772 | - | - |

| F. Eco-social Use | NA | (0.670) 0.546 ** | (0.669) 0.535 ** | (0.663) 0.543 ** | (0.440) 0.378 ** | (0.705) 0.593 ** | 0.780 | - |

| G. Eco-social Purchase | NA | (0.242) 0.195 ** | (0.289) 0.231 ** | (0.367) 0.305 ** | (0.341) 0.274 ** | (0.358) 0.299 ** | (0.373) 0316 ** | 0.868 |

| Predictor | Dependent Variable | Direct Effect * | S.D | p-Value | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injunctive Norms—Belief Strength | Integrated Norms | 0.239 (0.151, 0.332) | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.053 |

| Introjected Norms | 0.146 (0.056, 0.247) | 0.050 | 0.004 | 0.016 | |

| Eco-social Use | 0.187 (0.112, 0.260) | 0.038 | 0.000 | 0.047 | |

| Eco-social Purchase | −0.025 (−0.118, 0.066) | 0.046 | 0.604 | 0.000 | |

| Injunctive Norms—Motivations to Comply | Integrated Norms | 0.198 (0.101, 0.274) | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.037 |

| Introjected Norms | 0.158 (0.062, 0.252) | 0.048 | 0.001 | 0.019 | |

| Eco-social Use | 0.205 (0.121, 0.285) | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.060 | |

| Eco-social Purchase | 0.078 (−0.007, 0.177) | 0.047 | 0.101 | 0.005 | |

| Descriptive Norms | Integrated Norms | 0.236 (0.145, 0.321) | 0.047 | 0.000 | 0.060 |

| Introjected Norms | 0.142 (0.044, 0.228) | 0.047 | 0.000 | 0.018 | |

| Eco-social Use | 0.246 (0.168, 0.324) | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.097 | |

| Eco-social Purchase | 0.201 (0.098, 0.296) | 0.050 | 0.000 | 0.035 | |

| Introjected Norms | Eco-social Use | 0.015 (−0.048, 0.078) | 0.033 | 0.657 | 0.000 |

| Eco-social Purchase | 0.140 (0.041, 0.243) | 0.050 | 0.007 | 0.015 | |

| Integrated Norms | Eco-social Use | 0.314 (0.223, 0.401) | 0.045 | 0.000 | 0.113 |

| Eco-social Purchase | 0.113 (0.016, 0.209) | 0.050 | 0.025 | 0.008 |

| Predictor (X) | Consequent | Indirect Effect a | SD | t-Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator (M) | Dependent Variable (Y) | ||||

| Injunctive Norms—Belief Strength | Integrated norms | Eco-social Use | 0.074 ** (0.042, 0.107) | 0.017 | 4.487 |

| Introjected norms | 0.003 ns (−0.007, 0.013) | 0.005 | 0.416 | ||

| Integrated norms | Eco-social Purchase | 0.026 * (0.005, 0.054) | 0.013 | 2.105 | |

| Introjected norms | 0.020 ns (0.005, 0.046) | 0.010 | 1.947 | ||

| Injunctive Norms—Motivation to Comply | Integrated norms | Eco-social Use | 0.061 ** (0.032, 0.098) | 0.017 | 3.519 |

| Introjected norms | 0.002 ns (−0.007, 0.016) | 0.005 | 0.411 | ||

| Integrated norms | Eco-social Purchase | 0.024 ns (0.004, 0.049) | 0.012 | 1.882 | |

| Introjected norms | 0.022 * (0.006, 0.045) | 0.010 | 2.156 | ||

| Subjective Descriptive Norms | Integrated norms | Eco-social Use | 0.073 ** (0.039, 0.119) | 0.020 | 3.632 |

| Introjected norms | 0.001 ns (−0.007, 0.013) | 0.005 | 0.418 | ||

| Integrated norms | Eco-social Purchase | 0.026 ns (0.005, 0.062) | 0.014 | 1.865 | |

| Introjected norms | 0.019 ns (0.005, 0.046) | 0.010 | 1.948 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saleem, M.A.; Ismail, H.; Ali, R.A. Actions Speak Louder than Words: Investigating the Interplay between Descriptive and Injunctive Norms to Promote Alternative Fuel Vehicles. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179662

Saleem MA, Ismail H, Ali RA. Actions Speak Louder than Words: Investigating the Interplay between Descriptive and Injunctive Norms to Promote Alternative Fuel Vehicles. Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179662

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaleem, Muhammad A., Hina Ismail, and Rao Akmal Ali. 2021. "Actions Speak Louder than Words: Investigating the Interplay between Descriptive and Injunctive Norms to Promote Alternative Fuel Vehicles" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179662

APA StyleSaleem, M. A., Ismail, H., & Ali, R. A. (2021). Actions Speak Louder than Words: Investigating the Interplay between Descriptive and Injunctive Norms to Promote Alternative Fuel Vehicles. Sustainability, 13(17), 9662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179662