The Construction Industry as the Subject of Implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (the Case of Poland)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

- Owners and managers of small construction enterprises perceive CSR activities only as a cost that will not bring any additional benefits.

- conducting a registered business activity,

- whose activities, in accordance with the Polish Classification of Activities, are carried out under section F, division 41: works related to the erection of buildings,

- not in bankruptcy or liquidation,

- operating in Poland.

4. Results

4.1. Scope of Implementation

4.2. Motivations

4.3. Barriers

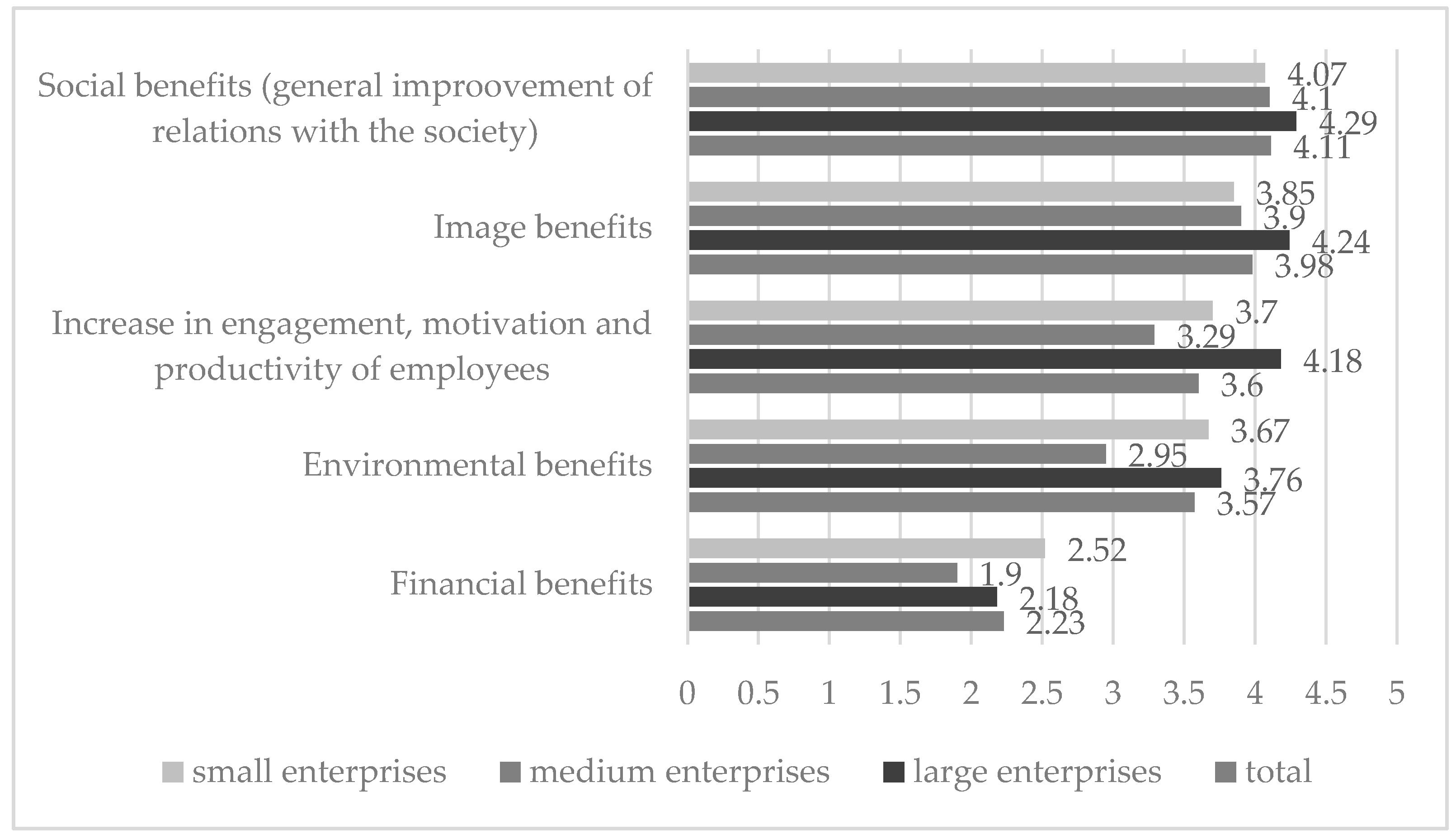

4.4. Benefits

5. Discussion

- the existence of a large potential in the implementation of CSR in construction industry enterprises. Our study confirmed that less than 40% of enterprises in Poland consciously implement it, which also translates to the results of other researchers regarding other countries [62,63] and confirms that this is an industry where there is a great need for such activities [64];

- the significant dependence of potential and motivation in implementing CSR on company size, turnover, seniority, and origin of capital. The general regularity is that the larger the enterprise and the higher the share of foreign capital (presumably a higher level of internationalisation), the higher the propensity and effectiveness of implementing measures (Table 10);

- the perception of benefits from the implementation of CSR is related to the size of the enterprise, the only benefit that is ‘strengthening the enterprise’s image outside’ was indicated as significant by enterprises from each of the size ranges, the others show greater differentiation. Similar conclusions were reached i.a. by Laudal [30], Santoso and Feliana [65] or Graafland [66].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lou, E.C.W.; Lee, A.; Mathison, G. Recapitulation of corporate social responsibility (CSR) for construction SMEs in the UK. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual ARCOM Conference, Bristol, UK, 5–7 September 2011; Egbu, C., Lou, E.C.W., Eds.; Association of Researchers in Construction Management: Bristol, UK, 2011; pp. 673–682. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, J. The state of sustainability reporting in the construction sector. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2012, 1, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladinrin, T.O.; Ogunsemi, D.R.; Aje, I.O. Role of Construction Sector in Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence from Nigeria. FUTY J. Environ. 2012, 7, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Bakış, A. Sustainability in Construction Sector. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seriki, O.O. Looking through the African lenses: A critical exploration of the CSR activities of Chinese International Construction Companies (CICCs) in Africa. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2020, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinuzzi, A.; Kudlak, R.; Faber, C.; Wiman, A. CSR Activities and impacts of the construction sector. RIMAS Work Pap. 2011, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, M.; Bryde, D.; Fearon, D.; Ochieng, E. Stakeholder Engagement: Achieving Sustainability in the Construction Sector. Sustainability 2013, 5, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Z.-Y.; Zhao, X.-J.; Davidson, K.; Zuo, J. A corporate social responsibility indicator system for construction enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 29, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaburda, M.; Bernaciak, A. Environmental protection in the perspective of CSR activities undertaken by polish enterprises of the construction industry. Econ. Environ. 2020, 75, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.X.; Couani, P. Managing risks in green building supply chain. Arch. Eng. Des. Manag. 2012, 8, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, R.; Loosemore, M. Breaking down the site hoardings: Attitudes and approaches to community consultation during construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2014, 32, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wong, J.K. Key activity areas of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the construction industry: A study of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea, A.S.; Popa, I. Legitimacy Theory. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Idowu, S.O., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., Gupta, A.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 21, pp. 1579–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, J.; Larrinaga-González, C.; Moneva-Abadía, J.M. Legitimating reputation/the reputation of legitimacy theory. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janang, J.S.; Joseph, C.; Said, R. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Society Disclosure: The Application of Legitimacy Theory. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 21, 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, G.; Wyrwicka, M.K.; Krugiełka, A. Socially responsible activities in medium-sized enterprises and their perception by students and graduates of selected universities in Greater Poland. Manag. Probl. 2010, 8, 182–201. [Google Scholar]

- Oczkowska, R. The Development and Implementation of CSR in Polish Retailing. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Krakowie. Sci. J. Krakow Univ. Econ. 2012, 880, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak, M.; Wołoszyn, J.; Stawicka, E. Concept of CSR in the aspect of employees on the example of agribusiness enterprises from Mazowieckie Voivodeship. Polityka ekonomiczna. Prace Naukowe UE we Wrocławiu. Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. Econ. Policy 2012, 246, 381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski, R. The Practice of CSR Implementation in Polish Companies According to the CSR Advisors. Annales. Etyka w życiu gospodarczym (Ann. Ethics Econ. Life) 2016, 19, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piskalski, G. Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Biznesu w Polskich Realiach. Teoria a Praktyka, Raport z Monitoringu Społecznej Odpowiedzi-alności Największych Polskich Przedsiębiorstw (Corporate Social Responsibility in the Polish Reality. Theory and Practice, Report on the Monitoring of the Social Responsibility of the Largest Polish Enterprises); Fundacja CentrumCSR.PL: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak, M. Implementation of key components of CSR concept in small and medium-sized enterprises of agribusiness from Lesser Poland. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2015, 402, 307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Gołata, K. Corporate social responsibility and the destruction of the company’s image. Legal Econ. Sociol. Mov. 2017, 79, 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Strategy for the Sustainable Competitiveness of the Construction Sector and Its Enterprises. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52012DC0433 (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Loosemore, M.; Lim, B.T.H. Linking corporate social responsibility and organizational performance in the construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liston-Heyes, C.; Ceton, G.C. Corporate social performance and politics: Do liberals do more? J. Corp. Citizensh. 2007, 25, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, E. Strategic CSR: A panacea for profit and altruism? An empirical study among executives in the Bangladeshi RMG supply chain. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2017, 29, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G.; Phillips, H.C.; Lyall, J. Corporate social responsibility and economic performance in the top British companies: Are they linked? Eur. Bus. Rev. 1998, 98, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papasolomou-Doukakis, I.; Krambia-Kapardis, M.; Katsioloudes, M. Corporate social responsibility: The way forward? Maybe not! A preliminary study in Cyprus. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2005, 17, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.J. CSR in SMEs: Strategies, practices, motivations and obstacles. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 32, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudal, T. Drivers and barriers of CSR and the size and internationalization of firms. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus-Leppan, T.; Metcalf, L.; Benn, S. Leadership Styles and CSR Practice: An Examination of Sensemaking, Institutional Drivers and CSR Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanesh, G.S. Why Corporate Social Responsibility? An Analysis of Drivers of CSR in India. Manag. Commun. Q. 2015, 29, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P.; Garde Sánchez, R.; López Hernández, A.M. Managers as drivers of CSR in state-owned enterprises. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 777–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.; Smid, H. Decoupling Among CSR Policies, Programs, and Impacts: An Empirical Study. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 231–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Kakakhel, S.J. An exploratory evidence of practice, motivations, and barriers to corporate social responsibility (CSR) in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakhtunkhwa (KPK). Abasyn J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 9, 479–494. [Google Scholar]

- Cera, G.; Belas, J.; Marousek, J.; Cera, E. Do size and age of small and medium-sized enterprises matter in corporate social responsibility? Econ. Sociol. 2020, 13, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudłak, R. Instytucjonalne uwarunkowania społecznej odpowiedzialności biznesu (Institutional Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility). Ph.D. Thesis, Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, Poznań, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Albareda, L.; Lozano, J.M.; Tencati, A.; Midttun, A.; Perrini, F. The changing role of governments in corporate social responsibility: Drivers and responses. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2008, 17, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, R.-J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Business, R.R.S.A.M. Drivers and customer satisfaction outcomes of CSR in supply chains in different institutional contexts. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Spena, T.; Tregua, M.; De Chiara, A. Trends and Drivers in CSR Disclosure: A Focus on Reporting Practices in the Automotive Industry. J. Bus. Ethic 2016, 151, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, I.M.; Ouschan, R.; Jarvis, W.; Soutar, G.N. Drivers and relationship benefits of customer willingness to engage in CSR initiatives. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2020, 30, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, A.; Falivena, C. Corporate social responsibility and firm value: Do firm size and age matter? Empirical evidence from European listed companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.S.; Canelas, C.; Chen, Y.-L. Relationships between Environmental Initiatives and Impact Reductions for Construction Companies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Mihai, L.S. An Integrated Framework on the Sustainability of SMEs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahidy, A.A.; Sorooshian, S.; Abd Hamid, Z. Critical Success Factors for Corporate Social Responsibility Adoption in the Construction Industry in Malaysia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popescu, C.R.G. Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Governance and Business Performance: Limits and Challenges Imposed by the Implementation of Directive 2013/34/EU in Romania. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Badulescu, A.; Badulescu, D.; Saveanu, T.; Hatos, R. The Relationship between Firm Size and Age, and Its Social Responsibility Actions—Focus on a Developing Country (Romania). Sustainability 2018, 10, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graafland, J.; van de Ven, B. Strategic and moral motivation for corporate social responsibility. J. Corp. Citizensh. 2006, 22, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grimstad, S.M.F.; Glavee-Geo, R.; Fjørtoft, B.E. SMEs motivations for CSR: An exploratory study. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2020, 32, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.; Kaptein, M.; Mazereeuw, C. Motives of socially responsible business conduct. Macroeconomics 2010, 74, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watts, G.; Dainty, A.; Fernie, S. Making sense of CSR in construction: Do contractor and client perceptions align. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual ARCOM Conference, Lincoln, UK, 7–9 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.; Eadie, R. Socially responsible procurement. A service innovation for generating employment in contruction. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2019, 9, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Oo, B.L.; Lim, B.T.H. Drivers, motivations, and barriers to the implementation of corporate social responsibility practices by construction enterprises: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lim, B.T.H.; Oo, B.L. Drivers, Motivations and Barriers for Being a Socially Responsible Firm in Construction: A Critical Review. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Environmental Management, Science and Engineering (IWEMSE 2018), Xiamen, China, 10–25 January 2018; pp. 568–575. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul, Z.; Ibrahim, S. Executive and management attitudes towards corporate social responsibility in Malaysia. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2002, 2, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elving, W.J. Scepticism and corporate social responsibility communications: The influence of fit and reputation. J. Mark. Commun. 2013, 19, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, S.; Anderson-Macdonald, S.; Thomson, M. Overcoming the ‘Window Dressing’ Effect: Mitigating the Negative Effects of Inherent Skepticism Towards Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Olanipekun, A.; Chen, Q.; Xie, L.; Liu, Y. Conceptualising the state of the art of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the construction industry and its nexus to sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Perrini, F. Investigating Stakeholder Theory and Social Capital: CSR in Large Firms and SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigri, G.; Del Baldo, M. Sustainability Reporting and Performance Measurement Systems: How do Small—And Medium-Sized Benefit Corporations Manage Integration? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bazarnik, J.; Grabiński, T.; Kąciak, E.; Mynarski, S.; Sagan, A. Badania Marketingowe. Metody i Oprogramowanie Komputerowe (Marketing Research. Computer Methods and Software); Canadian Consortium of Management Schools, Akademia Ekonomiczna w Krakowie: Warszawa-Kraków, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, E.A.M.; Yung, P. Implementation of corporate social responsibility in Australian construction SMEs. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2015, 22, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, W.; Kowalczyk, R. How to achieve sustainability?-Employee’s point of view on company’s culture and CSR practice. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanipekun, A.O.; Oshodi, O.S.; Darko, A.; Omotayo, T. The state of corporate social responsibility practice in the construction sector. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2020, 9, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, A.H.; Feliana, Y.K. The Association Between Corporate Social Responsibility And Corporate Financial Performance. Issues Soc. Environ. Account. 2014, 8, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Put Reputation at Risk by Inviting Activist Targeting? An Empirical Test among European SMEs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Category | Sub-Themes | Most Frequent Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Drivers | policy pressure, market pressure, innovation and technology development | Critical stakeholders’ (e.g., clients, investor, shareholders customers, end-users, joint venture) demand or pressure, market shift; Competitor pressure (e.g., competitors’ CSR strategies) |

| Motivations | financial benefits, branding, reputation and image, relationship building, organizational culture, strategic business direction | Branding, image management, public reputation; Public expectation/pressure, media pressure; Organizational culture and awareness: core business value, personal values of the founder or entrepreneur, ethical beliefs and consideration, doing the right thing, business imperatives |

| Barriers | government policy, construction enterprise (business organization), the attributes of CSR, the stakeholder perspective, the construction industry | Lack of awareness, knowledge, and information within the organization; Lack of capacity and expertise; Lack of internal resources; Lack of strategic guidance and support from senior leaders or managers within the organization; The negative attitude within the organization |

| Employment Volume | Size of the General Population | Share of Enterprises in the General Population (%) | Number of Enterprises Surveyed | Share of Enterprises in the Test Sample (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| from 10 to 49 | 6543 | 88.55 | 106 | 59.89 |

| from 50 to 249 | 794 | 10.75 | 49 | 27.68 |

| 250 and above | 52 | 0.70 | 22 | 12.43 |

| Σ | 7389 | 100 | 177 | 100 |

| Surveyed Enterprises | N = 177 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Number of Observations | Percentage of Observation in the Research Sample (in%) | |

| Origin of capital (ownership form) | only domestic | 155 | 87.57 |

| only foreign | 6 | 3.39 | |

| mixed with foreign capital participation | 16 | 9.04 | |

| Annual turnover in the year under review in EUR million | up to EUR 10 million | 114 | 64.41 |

| above EUR 10 million up to EUR 50 million | 43 | 24.29 | |

| over EUR 50 million | 20 | 11.30 | |

| Market presence in years | up to 10 years | 57 | 32.20 |

| over 10 years to 20 years | 36 | 20.34 | |

| over 20 years | 84 | 47.46 | |

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables |

|---|---|

| enterprise size annual turnover time of presence on the market capital ownership | scope of CSR activities carried out by enterprises motives for implementing CSR concepts barriers to implementing CSR concepts benefits of implementing CSR concepts disadvantages of implementing CSR concepts |

| Description | Total | Company Size | Origin of Capital | Annual Turnover (EUR Million) | Market Presence (Years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | Domestic | Foreign and Mixed 1 | ≤10 | >10 ≤50 | >50 | ≤10 | >10 ≤20 | >20 | ||

| Yes | 63 | 25 | 43 | 77 | 33 | 68 | 22 | 53 | 85 | 30 | 36 | 42 |

| No | 37 | 75 | 57 | 23 | 67 | 32 | 78 | 47 | 15 | 70 | 64 | 58 |

| N | 177 | 106 | 49 | 22 | 155 | 22 | 114 | 43 | 20 | 57 | 36 | 84 |

| No | Barriers | Dominant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Companies | ||||

| Small | Medium | Large | ||

| 1 | Lack of knowledge about the benefits | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | Lack of time | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| 3 | Lack of support and advisory institutions | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | Lack of awareness of the existence of CSR | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| 5 | Lack of suitable staff | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 6 | Lack of immediate effects | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | Lack of knowledge of the management in this field | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 8 | Lack of commitment and awareness of the management | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 9 | Complexity of the issues | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 10 | Costs of implementing and implementing CSR | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 11 | Lack of legislation on CSR | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 12 | Difficult economic situation of the enterprise | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | Economic crisis | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Variable | Component | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Lack of knowledge of the management in this field | 0.875 | - |

| Lack of support and advisory institutions | 0.873 | - |

| Difficult economic situation of the enterprise | - | 0.828 |

| Economic crisis | - | 0.824 |

| No | Benefits | Dominant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Companies | ||||

| Small | Medium | Large | ||

| 1 | Increase in sales of services | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | Enhancing the enterprise’s good external image | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | Solving an urgent/important social problem | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | Increased trust on the part of local authorities | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 5 | Increased motivation and identification of employees with the company | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 6 | Contribution to the improvement of environmental protection | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 7 | Increase in investors’ interest | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 8 | Increase in competitiveness | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 9 | Improving relations with the local community | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 10 | Increase in the enterprise’s profitability | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 11 | Better access to financial capital | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 12 | Introduction/enhancement of environmental technologies | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 13 | Application of CSR principles by suppliers and subcontractors | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| No | Disadvantages | Dominant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Companies | ||||

| Small | Medium | Large | ||

| 1 | Generating high costs | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | Reduction of the enterprise’s efficiency | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Lack of public understanding and broader acceptance of such activities | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | Conflicts between different stakeholder groups about their own interests | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 5 | Reduction of competitiveness on the market | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | Restriction of the enterprise’s development | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | Departure from the profit maximisation principle | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Category | Most Frequent Attributes | Most Frequent Attributes in Poland |

|---|---|---|

| Motivations | Branding, image management, public reputation; Public expectation/pressure, media pressure; Organizational culture and awareness: core business value, personal values of the founder or entrepreneur, ethical beliefs and consideration, doing the right thing, business imperatives | Social benefits, image benefits, increase in engagement, motivation and productivity of employees, environmental benefits, financial benefits |

| Barriers | Lack of awareness, knowledge, and information within the organization; Lack of capacity and expertise; Lack of internal resources; Lack of strategic guidance and support from senior leaders or managers within the organization; The negative attitude within the organization | Lack of knowledge, time, support and advisory institutions; Lack of awareness of the existence of CSR; Lack of suitable staff; Lack of immediate effects; Complexity of the issues; Costs; Lack of legislations |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernaciak, A.; Halaburda, M.; Bernaciak, A. The Construction Industry as the Subject of Implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (the Case of Poland). Sustainability 2021, 13, 9728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179728

Bernaciak A, Halaburda M, Bernaciak A. The Construction Industry as the Subject of Implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (the Case of Poland). Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179728

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernaciak, Arnold, Małgorzata Halaburda, and Anna Bernaciak. 2021. "The Construction Industry as the Subject of Implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (the Case of Poland)" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179728