The Impact of Scarcity of Medical Protective Products on Chinese Consumers’ Impulsive Purchasing during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

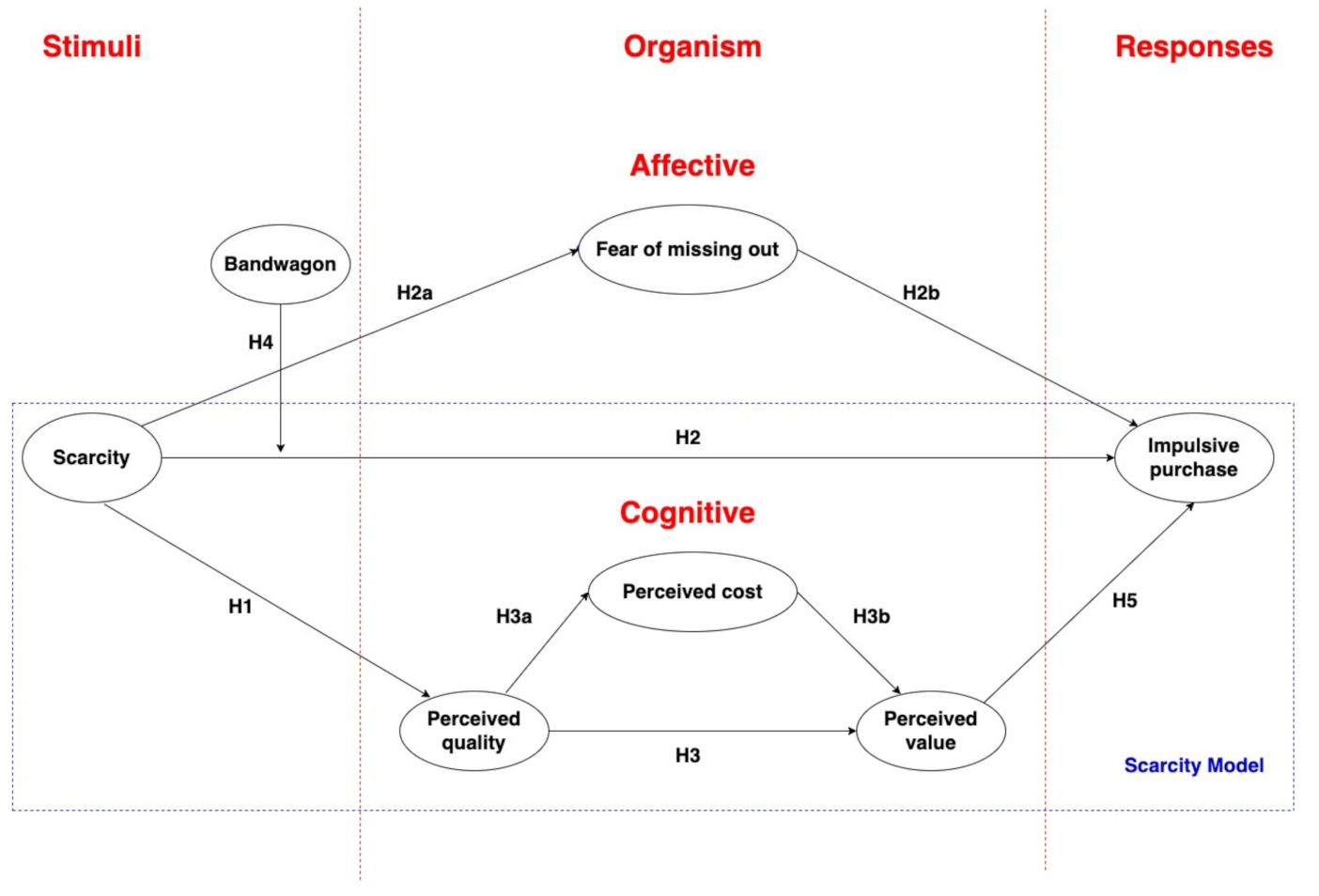

- To integrate relevant constructs from the theory of scarcity, S-O-R and bandwagon effect to develop multiple ways for explaining the scarcity effect on consumers’ impulsive purchasing;

- To find the influences of scarcity on impulsive purchasing by examining mediating ways such as fear of missing out and perception (perceived quality, perceived cost and perceived value);

- To examine the relationships between scarcity and perceived quality;

- To assess the mediating effect of perceived cost on the relationship between perceived quality and perceived value and the mediating effect of the fear of missing out on the relationship between scarcity and impulsive purchasing;

- To find the moderating effect of bandwagon on the relationship between scarcity and impulsive purchasing;

- To test the relationship between perceived value and impulsive purchasing.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Scarcity Model

2.2. S-O-R Model

2.3. Bandwagon Effect

2.4. Relationship between Scarcity and Perceived Quality

2.5. Relationship between Scarcity, Fear of Missing out and Impulsive Purchasing

2.6. Relationship between Perceived Quality, Perceived Cost and Perceived Value

2.7. Relationship between Scarcity, Bandwagon Effect and Impulsive Purchasing

2.8. Relationship between Perceived Value and Impulsive Purchasing

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Measurement and Scale

3.2. Sampling Design and Data Collection

4. Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

4.3. Discussion

5. Contributions

6. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Measurement Items |

|---|---|

| Scarcity |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Bandwagon |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Perceived quality |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Fear of Missing out |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Perceived cost |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Perceived value |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Impulsive purchasing |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

References

- Abel, J.P.; Buff, C.L.; Burr, S.A. Social media and the fear of missing out: Scale development and assessment. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2016, 4, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardin, M.A. COVID-19 and anxiety: A review of psychological impacts of infectious disease outbreaks. Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 15, e102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, K.; Hubacek, K.; Pfister, S.; Yu, Y.; Sun, L. Virtual scarce water in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7704–7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Chen, X.; Liu, T.; Li, P.; Wei, W.; Chao, M. The relationship between media involvement and death anxiety of self-quarantined people in the COVID-19 outbreak in China: The mediating roles of empathy and sympathy. OMEGA J. Death Dying 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, G.; Ji, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Mou, Q.; Shi, T. Analysis of the Influence of the Psychology Changes of Fear Induced by the COVID-19 Epidemic on the Body. World J. Acupunct. Moxibustion 2020, (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, X.; Zhu, X.; Fu, S.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Xiao, J. Psychological impact of healthcare workers in China during COVID-19 pneumonia epidemic: A multicenter cross-sectional survey investigation. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, T.; Huang, E.; Li, J. How does a public health emergency motivate people’s impulsive consumption? An empirical study during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Mathis, A.A.; Jobe, M.C.; Pappalardo, E.A. Clinically significant fear and anxiety of COVID-19: A psychometric examination of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Zhao, Y.J.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, X.H.; Zhao, N.; Cheung, T.; Ng, C.H. The COVID-19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: Managing challenges through mental health service reform. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, M.W.; Zhou, M.Y.; Ji, G.H.; Ye, L.; Cheng, Y.R.; Feng, Z.H.; Chen, J. Mask crisis during the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 24, 3397–3399. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, C.J.; He, Z.; Ming, W.K. Facemask shortage and the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak: Reflection on public health measures. MedRxiv 2020, 21, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.J.; Chien, S.H. Impulsive purchase, approach–avoidance effect, emotional account influence in online-to-offline services. J. Adv. Inf. Technol. 2019, 10, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Pitafi, A.H.; Arya, V.; Wang, Y.; Akhtar, N.; Mubarik, S.; Xiaobei, L. Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Li, E.Y. Marketing mix, customer value, and customer loyalty in social commerce: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 74–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.J.; Yun, Z.S. Consumers’ perceptions of organic food attributes and cognitive and affective attitudes as determinants of their purchase intentions toward organic food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, H.H.; Kuo, C.C.; Yang, Y.T.; Chung, T.S. Decision-contextual and individual influences on scarcity effects. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 1314–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Roy, R. Looking beyond first-person effects (FPEs) in the influence of scarcity appeals in advertising: A replication and extension of Eisend (2008). J. Advert. 2016, 45, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, M. Hoarding in the age of COVID-19. J. Behav. Econ. Policy 2020, 4, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kuruppu, G.N.; De Zoysa, A. COVID-19 and Panic Buying: An Examination of the Impact of Behavioural Biases. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labad, J.; González-Rodríguez, A.; Cobo, J.; Puntí, J.; Farré, J.M. A systematic review and realist synthesis on toilet paper hoarding: COVID or not COVID, that is the question. PeerJ. 2021, 9, e10771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, I.K.; Eru, O.; Cop, R. The effects of consumers’ FOMO tendencies on impulse buying and the effects of impulse buying on post-purchase regret: An investigation on retail stores. BRAIN. Broad Res. Artif. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Shi, Y. The impact of risk appetite on public purchasing behavior: Taking the purchase of masks as an example. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2020, 38, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- How to Protect the Rights and Interests of Buying Masks? The Reminder of Henan Consumers Association. Available online: https://4g.dahe.cn/news/20200219600294 (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Shanxi Consumers Association: Unite You and Me to Overcome Difficulties (COVID-19) Together. Available online: http://www.ce.cn/cysc/newmain/yc/jsxw/202002/04/t20200204_34216658.shtml (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Chaudhuri, H.R.; Majumdar, S. Of diamonds and desires: Understanding conspicuous consumption from a contemporary marketing perspective. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2006, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kristofferson, K.; McFerran, B.; Morales, A.C.; Dahl, D.W. The dark side of scarcity promotions: How exposure to limited-quantity promotions can induce aggression. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 43, 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, T.Y.; Yeh, T.L.; Wang, Y.J. The drivers of desirability in scarcity marketing. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 924–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.E.; Ko, Y.J.; Morris, J.D.; Chang, Y. Scarcity message effects on consumption behavior: Limited edition product considerations. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, N.G. The Effect of Scarcity Types on Consumer Preference in the High-End Sneaker Market. Ph.D. Thesis, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H.J.; Kwon, K.N. The effectiveness of two online persuasion claims: Limited product availability and product popularity. J. Promot. Manag. 2012, 18, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, T.; Figl, K. Consumers’ perceptions of different scarcity cues on e-commerce websites. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh Anh, K. Scarcity Effects on Consumer Purchase Intention in the Context of E-Commerce. Master’s Thesis, Aalto University School of Business, Espoo, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.Y.; Lu, H.Y.; Wu, Y.Y.; Fu, C.S. The effects of product scarcity and consumers’ need for uniqueness on purchase intention. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lennon, S.J. Effects of reputation and website quality on online consumers’ emotion, perceived risk and purchase intention. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2013, 7, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaf, F.; Tagg, S. Online shopping environments in fashion shopping: An SOR based review. Mark. Rev. 2012, 12, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodworth, R.S. Dynamic Psychology; Clark University Press: Worcester, MA, USA, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Bharathi, K.; Sudha, S. Store Ambiance Influence on Consumer Impulsive Buying Behavior towards Apparel: SOR Model. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2017, 8, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopdar, P.K.; Balakrishnan, J. Consumers response towards mobile commerce applications: Sor approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floh, A.; Madlberger, M. The role of atmospheric cues in online impulse-buying behavior. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainolfi, G. Exploring materialistic bandwagon behaviour in online fashion consumption: A survey of Chinese luxury consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Ha, J.; Park, J.Y. An experimental investigation on the determinants of online hotel booking intention. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, S.; Aneela, M.; Akram, M.S.; Ronika, C. Do luxury brands successfully entice consumers? The role of bandwagon effect. Int. Mark. Rev. 2017, 34, 498–513. [Google Scholar]

- Tynan, C.; McKechnie, S.; Chhuon, C. Co-creating value for luxury brands. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.W.; Sim, C.C. Aggregate bandwagon effect on online videos’ viewership: Value uncertainty, popularity cues, and heuristics. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 2382–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A. Bandwagon effect and network externalities in market demand. Asian J. Manag. Res. 2014, 4, 527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, A.; Ghafar, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Yousuf, M.; Ahmed, N. Product perceived quality and purchase intention with consumer satisfaction. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2015, 15, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Shuey, K.N. The Effects of Discount Level and Scarcity on the Perceived Product Value in Email Advertising. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, M. Scarcity’s enhancement of desirability: The role of naive economic theories. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 13, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cremer, S.; Loebbecke, C. Selling goods on e-commerce platforms: The impact of scarcity messages. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 47, 101039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierl, H.; Huettl, V. Are scarce products always more attractive? The interaction of different types of scarcity signals with products’ suitability for conspicuous consumption. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2010, 27, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Fung, B.C.; Chen, Z.; Gao, X. A cross-national study of apparel consumer preferences and the role of product-evaluative cues. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 796–812. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, T. What is value of investing? Buy paintings of Van Gogh, buy houses which is scarce. Real Estate Guide 2019, 7, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hayran, C.; Anik, L.; Gürhan-Canli, Z. A threat to loyalty: Fear of missing out (FOMO) leads to reluctance to repeat current experiences. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, C. Fear of Missing Out’ (FOMO) marketing appeals: A conceptual model. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiménez, F.R.; Cicala, J.E. Fear of missing out scale: A self-concept perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, B.C.; Flett, J.A.M.; Hunter, J.A.; Scarf, D.; Conner, T.S. Fear of missing Out (FOMO): The relationship between FOMO, alcohol use, and alcohol-related consequences in college students. Ann. Neurosci. Psychol. 2015, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moon, M.A.; Farooq, A.; Kiran, M. Social shopping motivations of impulsive and compulsive buying behaviors. UW J. Manag. Sci. 2017, 1, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, V. Study on impulsive buying behavior among consumers in supermarket in Kathmandu Valley. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 1, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalla, S.M.; Arora, A.P. Impulse buying: A literature review. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2011, 12, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.L.; Yazdanifard, R. What internal and external factors influence impulsive buying behavior in online shopping? Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2015, 15, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.Y.; Lim, K.H. Nudging moods to induce unplanned purchases in imperfect mobile personalization contexts. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 57–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mertens, G.; Gerritsen, L.; Duijndam, S.; Salemink, E.; Engelhard, I.M. Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): Predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swennen, G.R.; Pottel, L.; Haers, P.E. Custom-made 3D-printed face masks in case of pandemic crisis situations with a lack of commercially available FFP2/3 masks. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Li, F.; Chumnumpan, P. The use of product scarcity in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 380–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Föbker, N. Can You Resist? The Influence of Limited-Time Scarcity and Limited-Supply Scarcity on Females and Males in Hotel Booking Apps. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Twente, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, H. Explaining the effects of fear of missing the developments in social media (Fomo) on Instinctive Purchases by self-determination theory. Int. J. Econ. Adm. Stud. 2018, 17, 415–426. [Google Scholar]

- Rajh, S.P. Comparison of perceived value structural models. Market/Tržište 2012, 24, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Salim, T.; Onyia, O.P.; Harrison, T.; Lindsay, V. Effects of perceived cost, service quality, and customer satisfaction on health insurance service continuance. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2017, 22, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lizin, S.; Van Passel, S.; Schreurs, E. Farmers’ perceived cost of land use restrictions: A simulated purchasing experiments. Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Liang, L. Policy implications for promoting the adoption of electric vehicles: Do consumer’s knowledge, perceived risk and financial incentive policy matter? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 117, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Kumari, N. Consumer perceived value. Int. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark. 2012, 6, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.R.; Lehmann, D.R. When shelf-based scarcity impacts consumer preferences. J. Retail. 2011, 87, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.J.; Sun, T.H. Clarifying the impact of product scarcity and perceived uniqueness in buyers’ purchase behaviour of games of limited-amount version. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2014, 26, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herpen, E.; Pieters, R.; Zeelenberg, M. When demand accelerates demand: Trailing the bandwagon. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Lv, X.; Li, H. To buy or not to buy? The effect of time scarcity and travel experience on tourists’ impulse buying. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 103083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.C.; Yurchisin, J. Fast fashion environments: Consumer’s heaven or retailer’s nightmare? Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gentry, J.W. Should I buy, hoard, or hide? -consumers’ responses to perceived scarcity. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2019, 29, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.W.; Yan, S.R.; Zhou, J.L.; Kaluri, R. Cross-Border Shopping on Consumer Satisfaction Survey–The Case of COVID-19 was Analyzed; Scholars Middle East Publishers: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, K. Impact of the First Phase of Movement Control Order during the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia on purchasing behavior of Malaysian Consumers Kamaljeet Kaur1*, Mageswari Kunasegaran2, Jaspal Singh3, Selvi Salome4, and Sukjeet Kaur Sandhu5. Horizon 2020, 2, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Favier, M.; Huang, P.; Coat, F. Chinese consumer perceived risk and risk relievers in e-shopping for clothing. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciolatti, L.; Lee, S.H. Revisiting the relationship between marketing capabilities and firm performance: The moderating role of market orientation, marketing strategy and organisational power. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5597–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Firman, A.; Putra, A.H.P.K.; Mustapa, Z.; Ilyas, G.B.; Karim, K. Re-conceptualization of Business Model for Marketing Nowadays: Theory and Implications. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joensuu-Salo, S.; Sorama, K.; Viljamaa, A.; Varamäki, E. Firm performance among internationalized SMEs: The interplay of market orientation, marketing capability and digitalization. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oakes, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 119, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Serhan, O. The Impact of Religiously Motivated Boycotts on Brand Loyalty among Transnational Consumers. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, A.Y.L. Understanding mobile commerce continuance intentions: An empirical analysis of Chinese consumers. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2013, 53, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair Jr, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) an emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modelling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl. 2010, 11, 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Loxton, M.; Truskett, R.; Scarf, B.; Sindone, L.; Baldry, G.; Zhao, Y. Consumer behaviour during crises: Preliminary research on how coronavirus has manifested consumer panic buying, herd mentality, changing discretionary spending and the role of the media in influencing behaviour. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazlan, N.H.; Tanford, S.; Raab, C.; Choi, C. The influence of scarcity cues and price bundling on menu item selection. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modin, Z.; Smith, Q. Impulsive Buying Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Master’s Thesis, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Leng, X.; Liu, S. Research on mobile impulse purchase intention in the perspective of system users during COVID-19. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2020, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Measure | Item | Frequency | Percent% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 221 | 43.4 |

| Female | 288 | 56.6 | |

| Age | 25 and under | 138 | 27.1 |

| 26–35 | 220 | 43.2 | |

| 36–45 | 93 | 18.3 | |

| 46–55 | 43 | 8.4 | |

| 56 over | 15 | 2.9 | |

| Occupation | Public official | 231 | 45.4 |

| Unemployed | 40 | 7.9 | |

| Retired | 12 | 2.4 | |

| Student | 107 | 21 | |

| Other | 119 | 23.4 | |

| Income (RMB) | 2500 or less | 157 | 30.8 |

| 2501–3500 | 114 | 22.4 | |

| 3501–4500 | 91 | 17.9 | |

| 4501–5500 | 73 | 14.3 | |

| 5501–6500 | 31 | 6.1 | |

| 6501 and above | 43 | 8.4 | |

| Education Level | High school (including technical secondary school) and lower | 97 | 19.1 |

| College degree | 164 | 32.2 | |

| Graduate degree | 205 | 40.3 | |

| Postgraduate degree and higher | 43 | 8.4 | |

| You are a medical worker | Yes | 41 | 8.1 |

| No | 468 | 91.9 | |

| Medical protective products are scarcity | Yes | 371 | 72.9 |

| No | 138 | 27.1 | |

| The high price of medical protective products | Yes | 392 | 77 |

| No | 117 | 23 | |

| Total | 509 | 100 |

| Constructs | CA | CR | AVE | Discriminate Validity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOMO | 0.873 | 0.922 | 0.797 | 0.893 | ||||||

| Bandwagon | 0.880 | 0.918 | 0.736 | 0.576 | 0.858 | |||||

| Impulsive Purchasing | 0.908 | 0.932 | 0.732 | 0.521 | 0.572 | 0.855 | ||||

| Perceived Quality | 0.925 | 0.944 | 0.770 | 0.435 | 0.488 | 0.469 | 0.878 | |||

| Perceived Cost | 0.900 | 0.930 | 0.770 | 0.527 | 0.510 | 0.557 | 0.456 | 0.878 | ||

| Perceived Value | 0.830 | 0.888 | 0.666 | 0.537 | 0.599 | 0.509 | 0.541 | 0.555 | 0.816 | |

| Scarcity | 0.880 | 0.912 | 0.675 | 0.492 | 0.525 | 0.493 | 0.515 | 0.639 | 0.535 | 0.822 |

| Hypotheses | Path | Std. Beta (β) | t-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Scarcity→Perceived quality | 0.515 | 12.390 | Supported |

| H2 | Scarcity→Impulsive purchasing | Supported | ||

| Total effect | 0.338 | 6.426 | ||

| Direct effect | 0.224 | 4.003 | ||

| Indirect effect | 0.082 | 3.003 | ||

| H3 | Perceived quality→Perceived value | Supported | ||

| Total effect | 0.541 | 13.547 | ||

| Direct effect | 0.364 | 7.510 | ||

| Indirect effect | 0.177 | 6.613 | ||

| H4 | Moderating Effect 1→Impulsive purchasing | 0.136 | 3.679 | Supported |

| H5 | Perceived value→Impulsive purchasing | 0.115 | 1.967 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Jiang, N.; Turner, J.J.; Pahlevan Sharif, S. The Impact of Scarcity of Medical Protective Products on Chinese Consumers’ Impulsive Purchasing during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179749

Zhang J, Jiang N, Turner JJ, Pahlevan Sharif S. The Impact of Scarcity of Medical Protective Products on Chinese Consumers’ Impulsive Purchasing during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179749

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jingjing, Nan Jiang, Jason James Turner, and Saeed Pahlevan Sharif. 2021. "The Impact of Scarcity of Medical Protective Products on Chinese Consumers’ Impulsive Purchasing during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179749