Investigating Moderators of the Influence of Enablers on Participation in Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Group Norms Governing VCs

2.2. Intrinsic Motivation for Knowledge Sharing in VCs

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Types of Self-Awareness

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Level of Anonymity

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measurements

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Validation

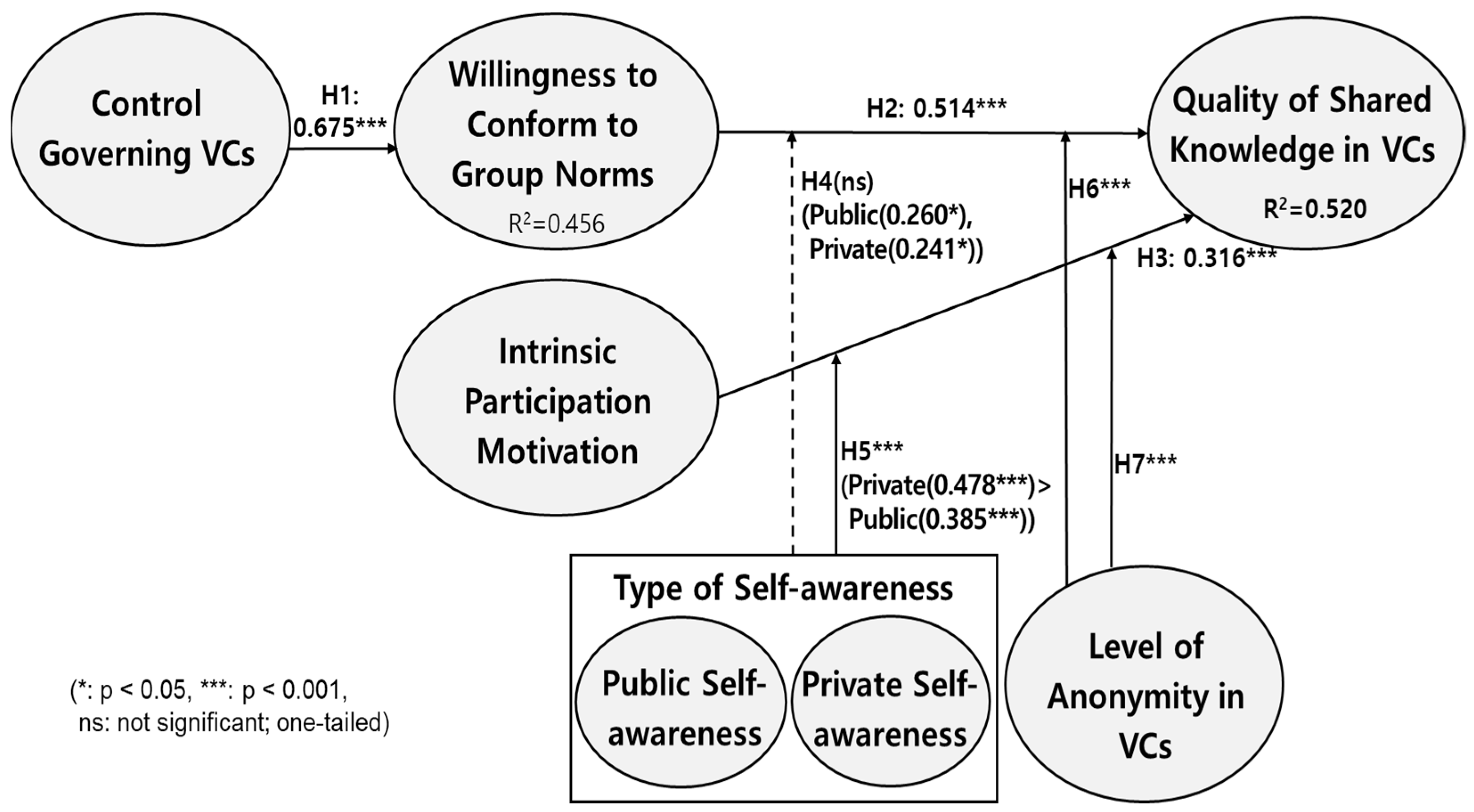

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Findings and Discussion

5.2. Contributions and Implications

5.3. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lechner, U.; Hummel, J. Business models and system architectures of virtual communities: From a sociological phenomenon to peer-to-peer architectures. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2002, 6, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S.; Orlikowski, W. Entanglements in practice: Performing anonymity through social media. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 873–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Intentional social action in virtual communities. J. Interact. Mark. 2002, 16, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.H.; Chiu, C.M. In justice we trust: Exploring knowledge-sharing continuance intentions in virtual communities of practice. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingshead, A.B. Dynamics of leader emergence in online groups. In Strategic Uses of Social Technology: An Interactive Perspective of Social Psychology; Birchmeier, Z., Dietz-Uhler, B., Stasser, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.M.; Hsu, M.H.; Wang, E.T. Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.J.J.; Hung, S.W.; Chen, C.J. Fostering the determinants of knowledge sharing in professional virtual communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F. Determinants of successful virtual communities: Contributions from system characteristics and social factors. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luarn, P.; Hsieh, A.Y. Speech or silence: The effect of user anonymity and member familiarity on the willingness to express opinions in virtual communities. Online Inf. Rev. 2014, 38, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, A.; Shin, K.S.; Lee, J. The Effects of Multi-identity on One’s Psychological State and the Quality of Contribution in Virtual Communities: A Socio-Psychological Perspective. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2010, 20, 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Siponen, M. Why do adults engage in cyberbullying on social media? An integration of online disinhibition and deindividuation effects with the social structure and social learning (SSSL) model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2016, 27, 962–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reicher, S.D.; Spears, R.; Postmes, T. A social identity model of deindividuation phenomenon. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 6, 161–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.S.; McLeod, D.M. Social-psychological influences on opinion expression in face-to-face and computer-mediated communication. Commun. Res. 2008, 35, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.K.; Lee, A.R.; Lee, U.K. Impact of anonymity on roles of personal and group identities in online communities. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodzicki, K.; Schwämmlein, E.; Cress, U.; Kimmerle, J. Does the type of anonymity matter? The impact of visualization on information sharing in online groups. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopherson, K. The positive and negative implications of anonymity in Internet social interactions: ‘On the Internet, Nobody Knows You’re a Dog’. Comput. Human Behav. 2007, 23, 3038–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P.G. The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Arnold, W.J., Levine, D., Eds.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Stets, J.E. Role identities and person identities: Gender identity, mastery identity, and controlling one’s partner. Sociol. Perspect. 1995, 38, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.; Rolland, E. Knowledge-sharing in virtual communities: Familiarity, anonymity and self-determination theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2012, 31, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, U.K.; Lee, A.R.; Kim, K.K. The Effect of Anonymity on Virtual Team Performance in Online Communities. J. Soc. e-Bus. Stud. 2015, 20, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D. Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, E.; Weingart, L.R. Group goals and group performance. Brit. J. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 32, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.S.; Bateman, P.J.; Gray, P.H.; Diamant, E.I. An attraction–selection–attrition theory of online community size and resilience. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 699–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadin, T.; Gnambs, T.; Batinic, B. Personality traits and knowledge sharing in online communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.M.; Chen, T.T. Knowledge sharing in interest online communities: A comparison of posters and lurkers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, S.; Kudaravilli, S.; Wasko, M. Leading collaboration in online communities. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, P.L.; Smith, S.G.; Zinkiewicz, L. An exploration of sense of community, part 3: Dimensions and predictors of psychological sense of community in geographical communities. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 30, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Trost, M. Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed.; Gilbert, D., Fiske, S., Lindzey, G., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Postmes, T.; Spears, R.; Sakhel, K.; de Groot, D. Social influence in computer-mediated communication: The effects of anonymity on group behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaturi, K.; Chua, C.E.H. Framing Group Norms in Virtual Communities. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 15–17 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Majchrzak, A.; Malhotra, A.; John, R. Perceived individual collaboration know-how development through information technology–enabled contextualization: Evidence from distributed teams. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, E. The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D. On the Conflicts Between Biological and Social Evolution and Between Psychology and Moral Tradition. Zygon J. Relig. Sci. 1976, 11, 167–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Culture and Social Behavior; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asch, S.E. Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1956, 70, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crutchfield, R.S. Conformity and character. Am. Psychol. 1955, 10, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, V.L. Situational factors in conformity. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 2, 133–175. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, M.; Gerard, H.B. A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1955, 51, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M.; Hill, K.G.; Hennessy, B.A.; Tighe, E.M. The work preference inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 950–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S.; Chang, S.F.; Liu, C.H. Understanding knowledge-sharing motivation, incentive mechanisms, and satisfaction in virtual communities. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2012, 40, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, R.; Hao, J.X.; Chen, X. Motivation factors of knowledge collaboration in virtual communities of practice: A perspective from system dynamics. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 466–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Li, D.; Hou, W. Task design, motivation, and participation in crowdsourcing contests. Int. J. Electron. Comm. 2011, 15, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination theory: A view from the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 312–318. [Google Scholar]

- Füller, J. Refining virtual co-creation from a consumer perspective. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2010, 52, 98–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, K.R.; Von Hippel, E. How open source software works: “Free” user-to-user assistance. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 923–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Elmore, K.; Smith, G. Self, self-concept, and identity. In Handbook of Self and Identity, 2nd ed.; Leary, M.R., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 69–104. [Google Scholar]

- Vignoles, V.L.; Regalia, C.; Manzi, C.; Golledge, J.; Scabini, E. Beyond self-esteem: Influence of multiple motives on identity construction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 308–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. Deindividuation and the self-regulation of behavior. In The Psychology of Group Influence, 2nd ed.; Paulus, P.B., Ed.; Lawence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Trafimow, D.; Triandis, H.C.; Goto, S.G. Some tests of the distinction between the private self and the collective self. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govern, J.M.; Marsch, L.A. Development and validation of the situational self-awareness scale. Conscious. Cogn. 2001, 10, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froming, W.; Walker, R.; Lopyan, K. Public and private self-awareness: When personal attitudes conflict with societal expectations. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 18, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C. The analysis of social influence. In Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 68–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, B.; Migdal, M.J.; Rozell, D. Self-awareness, deindividuation, and social identity: Unraveling theoretical paradoxes by filling empirical lacunae. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimeister, J.M.; Ebner, W.; Krcmar, H. Design, implementation, and evaluation of trust-supporting components in virtual communities for patients. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 2, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.Y.; Kim, S.S. Internet Users’ Information Privacy-Protective Responses: A Taxonomy and a Nomological Model. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 503–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spears, R.; Lea, M. Panacea or Panopticon? The hidden power in computer-mediated communication. Commun. Res. 1994, 21, 427–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Croft, W.B.; Smith, D.A. Online community search using thread structure. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Hong Kong, China, 2 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Faraj, S.; Johnson, S.L. Network exchange patterns in online communities. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butler, B.S. Membership size, communication activity, and sustainability: A resource-based model of online social structures. Inf. Syst. Res. 2001, 12, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Huang, L.; Dou, W. Social factors in user perceptions and responses to advertising in online social networking communities. J. Interact. Advert. 2009, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsonneault, A.; Heppel, N. Anonymity in group support systems research: A new conceptualization, measure, and contingency framework. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1997, 14, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and voice mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.C. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hess, T.J.; Fuller, M.; Campbell, D.E. Designing interfaces with social presence: Using vividness and extraversion to create social recommendation agents. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2009, 10, 889–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings, 5th ed.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.K.; Umanath, N.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Ahrens, F.; Kim, B. Knowledge complementarity and knowledge exchange in supply channel relationships. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 32, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, M.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.; Saarinen, T.; Tuunainen, V.; Wassenaar, A. A Cross-cultural Study on Escalation of Commitment Behavior in Software Projects. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, C.W.; Kankanhalli, A.; Sabherwal, R. Usability and sociability in online communities: A comparative study of knowledge seeking and contribution. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2009, 10, 721–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, H.L.; Forde, P.J. Internet anonymity practices in computer crime. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2003, 11, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 152 | 50.2 |

| Female | 151 | 49.8 | |

| Age | 10–19 | 9 | 3.0 |

| 20–29 | 106 | 35.0 | |

| 30–39 | 104 | 34.3 | |

| 40–49 | 49 | 16.2 | |

| 50–59 | 26 | 8.6 | |

| Over 60 | 9 | 3.0 | |

| Member’s Community Tenure | Less than 1 month | 33 | 10.9 |

| 1–6 months | 40 | 13.2 | |

| 6 months–1 year | 36 | 11.9 | |

| 1 year–3 years | 65 | 21.5 | |

| Longer than 3 years | 129 | 42.6 | |

| Level of Anonymity | Full anonymity | 62 | 20.5 |

| Partial anonymity | 225 | 74.3 | |

| Real name | 16 | 5.3 | |

| Variable | Operationalized Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Control governing VCs | The degree of control by which members perceive that the VC is well governed | [61] |

| Willingness to conform to group norms | The degree to which VC members are willing to conform to norms established for the benefit of the community as a whole | [62] |

| Intrinsic participation motivation | The degree to which a member is intrinsically motivated to participate in the VC because he or she feels interested in and intrinsically satisfied by being active in the VC | [43] |

| Public self-awareness | The degree to which an individual is conscious and aware of his or her self as seen by others | [63] |

| Private self-awareness | The degree to which an individual is conscious and aware of his or her inner self | [63] |

| Level of anonymity | The level of anonymity provided by the VC | [20] |

| Quality of shared knowledge | The quality of knowledge that is shared in the VC | [6] |

| Variable | Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Control governing VCs | This community encourages the active participation of its members. | [61] |

| This community imposes sanctions on members for inappropriate words and actions. | ||

| This community sets goals and strives to achieve them. | ||

| This community strives to ensure community cohesion. | ||

| Willingness to conform to group norms | I support actions that can benefit this community. | [62] |

| I try my best to do things that can be helpful for this community. | ||

| I am opposed to things that may harm this community. | ||

| I try to avoid doing things that could negatively impact this community. | ||

| Intrinsic participation motivation | I enjoy answering questions and posting good posts in this community. | [43] |

| I share my posts because sometimes, in this community, I think that good posts may not come out if I don’t reply or comment. | ||

| I endeavor to answer most questions about my area of expertise because I am pleased to answer them. | ||

| Public self-awareness | I am concerned about my style of doing things. | [63] |

| I am concerned about the way I present myself. | ||

| I am conscious of the way I look to others | ||

| I am usually worried about making a good impression on others. | ||

| I am concerned about what other people think of me. | ||

| Private self-awareness | I am aware of the way my mind works. | [63] |

| I always try to recognize the direction of my inner principles and beliefs when expressing my opinion. | ||

| I am examining my motives. | ||

| I am alert to changes in my mood. | ||

| I am trying to figure myself out. | ||

| I reflect on myself. | ||

| Level of anonymity | Choose the level of anonymity that is allowed in this community and that you are using: (1) Full anonymity (2) Partial anonymity (3) Real name | [20] |

| Quality of shared knowledge | The knowledge I share in this community is relevant to the topic. | [6] |

| The knowledge I share in this community is accurate. | ||

| The knowledge I share in this community is reliable. | ||

| The knowledge I share in this community is timely. |

| Construct | Factor Loading | AVE | Composite Reliability | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control governing VCs (CGV: 4 items) | 0.748 | 0.654 | 0.882 | 0.820 |

| 0.736 | ||||

| 0.874 | ||||

| 0.865 | ||||

| Willingness to conform to group norms (WCG: 4 items) | 0.860 | 0.731 | 0.916 | 0.877 |

| 0.891 | ||||

| 0.821 | ||||

| 0.847 | ||||

| Intrinsic participation motivation (IPM: 3 items) | 0.888 | 0.613 | 0.823 | 0.707 |

| 0.623 | ||||

| 0.815 | ||||

| Public self-awareness (PUS: 5 items) | 0.841 | 0.722 | 0.928 | 0.905 |

| 0.883 | ||||

| 0.872 | ||||

| 0.813 | ||||

| 0.838 | ||||

| Private self-awareness (PRS: 6 items) | 0.808 | 0.647 | 0.916 | 0.889 |

| 0.830 | ||||

| 0.825 | ||||

| 0.660 | ||||

| 0.855 | ||||

| 0.832 | ||||

| Quality of shared knowledge (QSK: 4 items) | 0.872 | 0.797 | 0.940 | 0.915 |

| 0.902 | ||||

| 0.918 | ||||

| 0.879 |

| PUS | WCG | IPM | PRS | QSK | CGV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PUS | 0.850 | |||||

| WCG | 0.549 | 0.855 | ||||

| IPM | 0.558 | 0.481 | 0.783 | |||

| PRS | 0.570 | 0.572 | 0.482 | 0.804 | ||

| QSK | 0.491 | 0.666 | 0.563 | 0.545 | 0.893 | |

| CGV | 0.529 | 0.675 | 0.584 | 0.560 | 0.697 | 0.808 |

| Path | Path Coefficient in Subgroup | Significance of Difference across Groups (t-Value by t-Test 1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Public Self-Awareness (n1 = 97) | High Private Self-Awareness (n2 = 84) | ||

| Willingness to conform to group norms → quality of shared knowledge | 0.260 * | 0.241 * | H4 Not Supported (1.069 (ns)) |

| Intrinsic participation motivation → quality of shared knowledge | 0.385 *** | 0.478 *** | H5 Supported (7.403 ***) |

| Path | Path Coefficient in Subgroup | Significance of Difference across Groups (t-Value by t-Test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Anonymity (n1 = 62) | Partial Anonymity (n2 = 255) | Real Name (n3 = 16) | ||

| Willingness to conform to group norms → quality of shared knowledge | 0.563 *** | 0.489 *** | 0.371 * | H6 supported (F vs. P: 7.670 *** F vs. R: 5.963 *** P vs. R: 6.124 ***) |

| Intrinsic participation motivation → quality of shared knowledge | 0.348 *** | 0.299 *** | 0.559 ** | H7 supported (F vs. P: 4.842 *** F vs. R: 6.758 *** P vs. R: 13.054 ***) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, A.R. Investigating Moderators of the Influence of Enablers on Participation in Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179883

Lee AR. Investigating Moderators of the Influence of Enablers on Participation in Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities. Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179883

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ae Ri. 2021. "Investigating Moderators of the Influence of Enablers on Participation in Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179883

APA StyleLee, A. R. (2021). Investigating Moderators of the Influence of Enablers on Participation in Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities. Sustainability, 13(17), 9883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179883