Participatory Urban Design for Touristic Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites: The Case of Negotinske Pivnice (Wine Cellars) in Serbia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Inclusive Approach to Heritage Management for Sustainable Tourism

1.2. Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites

1.3. Participatory Urban Design

1.3.1. Urban Design as Process and Product

1.3.2. Knowledge for Urban Design

1.3.3. Participation in Urban Design

1.4. The Case of “Negotinske Pivnice”(Wine Cellars of Negotin), Serbia

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

- How can local community participation contribute to the formation of the urban design knowledge base?

- How can local community knowledge and perception of WCN as a living place guide urban design and what kind of CHS presentation WCN PUD project enables?

- Are there differences between WCN locations in relation to their potential for CHS management and presentation?

2.2. Choice of the Case

2.3. Research Design

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. WCN PUD Project Location and Background

3.1.1. The Municipality of Negotin Location and Resources for Tourism Development

3.1.2. Wine Cellars of Negotin

3.1.3. History of WCN PUD Project

3.2. WCN PUD Project—Concept and Organisation

3.2.1. Goals, Assumptions and Expected Results

- How can an urban design process be used to support the involvement of local communities in WCN revitalization and presentation as CHS?

- How can urban design projects be used to present WCN as an existential space of local communities?

3.2.2. Theoretical Background and Research Methods

Participatory Approach to Urban Design Process

- Inclusion of variety of local stakeholders- actors

- Participation of local people in different phases of project

- Exploration of local people knowledge and relationship with WCN through different participation formats that enable the use of different research techniques

Existential Space Perspective to Urban Design Projects

3.2.3. WCN PUD Project Organization

WCN PUD Project Team

Limiting Factors in WCN PUD Process Organization

3.3. WCN PUD Process—Phases

3.3.1. Preparation

3.3.2. Field Research

- Both cultural and natural values of the region are important to participants

- Almost all participants had positive attitude towards the development of WCN for tourism

- Great majority of participants perceived WCN as important but recognized the need for their improvement in terms of renovation, public infrastructure and safety.

- Opinion about the character of the future relationship between WCN and village varied in accordance with the specificity of each case. It was highly rated in Rajac, Rogljevo and Smedovac, but inhabitants of Štubik didn’t show any interest in WCN.

3.3.3. Design

3.3.4. Presentation and Verification

3.4. WCN PUD Projects

3.4.1. Rajac

Context

Project

- Local communities’ key inputs to WCN presentation through UD

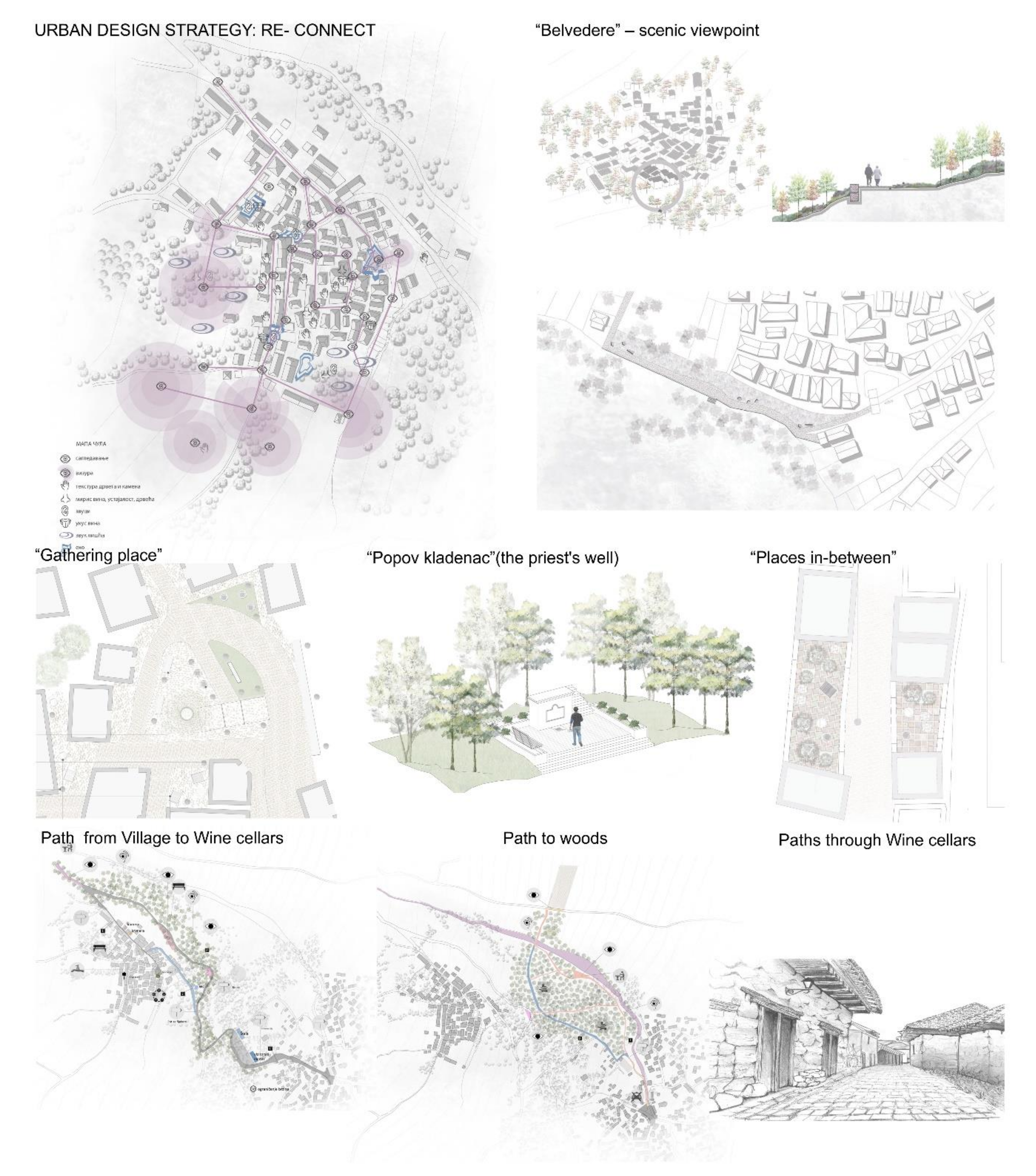

- UD Spatial Strategy (Figure 6)

- UD Projects for WCN Presentation (Figure 6):

- “Belvedere”—scenic viewpoint: designed for presenting the WC as a part of the rural landscape, with the use of local materials for ambient and educational purpose.

- “Gathering place”: designed as a “living display” of WC and a starting point for formal walking and guided tours. It is also supposed to function as place for lectures, events and activities for visitors. The place is equipped with new street lighting and furniture. Complex pattern of pavement with local materials was used for ambient and educational purpose.

- “Popov kladenac” (the priest’s well): Designed to support guided storytelling/lectures as well as to enable introspection, solitude and atmospheric experience

- “Places in-between”: designed to support everyday life and learning activities, as well as informal “display” of local life.

- “Path from the Village to Wine cellars”: designed to support walking and guided tours as well as multisensory experience of everyday local communication between two important areas of Rajac. It connects important focal points and is equipped with panels and signposts. Since visitor center is planned in the village—carriage can be used by tourists to get to wine cellars by using this route. Path is equipped with guideposts, benches and places to rest that can be used as guided tour stops.

- “Paths to woods”: these paths are designed by use of different local materials (gravel, grass, wood) and equipped by panels in order to present local nature and relationships within the cultural landscape. They connect specific places identified by locals (viewpoints, the murmur of water, bird habitats).

- “Paths through Wine cellars”: designed in order to present WC settlement as “living display” of wine-production and wine culture and to support a variety of touristic activities. New lighting was introduced, and local materials were used for ambient and educational purpose.

Integration of Local Knowledge into UD

3.4.2. Rogljevo

Context

Project

- Local communities’ key inputs to WCN presentation through UD

- UD Spatial Strategy (Figure 8)

- UD Projects for WCN presentation (Figure 8)

- “Path from the Village to Wine cellars”—presentation of local peoples’ everyday life and their functional and symbolical relation with the wine cellars is enabled by design of the path between “sounds and silence”. This path passes through different natural and built structures in WC and surroundings in which each stop “tells the story”, supported with specific design elements.

- “Gathering place”—this place is the “heart” of the WC, where local people gather during religious holidays and for all local events and celebrations. Several important structures are located here (Sabor, well and mulberry tree) and they form the specific ambient together with surrounding wine cellars. Design of pavement, street- light, and benches aims to present and shed light on both tangible and intangible values of this place as a “living display”. Also, it aims to enable a variety of touristic and presentational activities to take place (lectures, workshops, degustation and displays of local products), while at the same time keeping alive local traditional events and gatherings. This is a symbolic place of sounds in WC settlement of silence.

- Memorial drinking fountain—this is an important and symbolic place for local community and design project aimed to reveal it as such. Use of the greenery and local materials for walls and pavement, as well as discrete street light enable protection of the authenticity of place while at the same time enabling new activities of gathering in silence—for memory, meditation and contact with nature. At the same time this place is used as the starting point for tourist route that links village and WC.

- “Places in-between”—strategic design, lighting and the use of narrow segments between WC, amplifies the mysterious atmosphere and aims to support the creation of memorable touristic experiences.

Integration of Local Knowledge into UD

3.4.3. Štubik

Context

Project

- Local communities’ key inputs to WCN presentation through UD

- UD Spatial Strategy (Figure 10)

- UD Projects for WCN presentation (Figure 10)

- “Places in-between”—design of the canopy and pavement aimed to articulate space for lectures, events, activities for visitors as forms of CHS presentation.

- “Wetland”- design of the wooden path which connects segments of WC aimed to present specific relation between nature and local culture of wine production, and to create memorable experiences in walking and guided tours by contrasting ground levels, materials, vision and sounds of present and past.

Integration of Local Knowledge into UD

3.4.4. Smedovac

Context

Project

- Local communities’ key inputs to WCN presentation through UD

- UD Spatial Strategy (Figure 12)

- UD Projects for WCN presentation (Figure 12)

- “Orchestration”—spatial presentation strategy brings together and harmonise different aspects, actors, UD projects and timelines for their implementation. It applies and integrated view of designing, activating and presenting village, WC and cultural landscape.

- “School and Camp”—Reconstruction and adaptive use of the abandoned school as well as activation of its surroundings for Camping, is one of the key UD interventions, that aims to trigger future development with minimum investments. It aims to provide temporary, low-cost accommodation as well as the space for lectures, presentations, and workshops for young people and tourists.

- “Drinking Fountain and memorial”—This design project is located at the strategic point between village and WC aims to highlight local stories and history. It is an important display setting and a stop in walking and guided tours, where also lectures can take place due to new urban furniture.

- “Gathering Place”—The location consists of several important buildings that tell the story about the village and its viticulture. There are the old bell tower, gathering place building, new bell tower and the monument. By the use of different urban design elements (pavement by use of local materials, lighting, street furniture...), the project aims to enable the variety modes of presentation, while at the same time integrating the space into a unique whole that highlights the place itself as display of traditional rural architecture. Lectures, presentations of local products as well as a variety of activities for tourists and visitors are enabled through the establishment of the small “scene”.

- “Wine Streets”—the main goal of the project is to help tourists and visitors become aware of the variety and richness of the wine-cellars as both rural built heritage, part of viticulture and industrial archaeology. The different materialization of paths is used to stress different relations between the buildings, showcase the traditional use of local materials, and set thus the scene for walking and guiding tours.

- “Pavilions”—design for different wooden pavilions for different uses (“viewpoint”, “observatory”, “hedonism”, “swings”) was proposed and located in the nearby woods—in order to help experience and promote local viticulture, and rural landscape. At the same time, pavilions were supposed to be used as stops in guided and walking tours or for lectures and activities with visitors.

- “Signposts”—the network of signposts, info-panels and path directions was proposed at different locations in the village and WC as a part of presentation and communication infrastructure.

Integration of Local Knowledge into UD

4. Discussion

4.1. How Can Local Community Participation Contribute to Formation of UD Knowledge Base?

4.2. How Can Local Community Knowledge and Perception of WCN as Existential Space Guide Urban Design?

4.3. What Kind of CHS Presentation WCN PUD Project Enables?

Formal/Informal Presentation

Presentation Formats

4.4. Are There Differences between WCN Locations in Relation to Their Potential for CHS Management and Presentation?

- Location of WCN in relation to village. Spatial distance from village threats sustainability of WCN in the case of Štubik, while proximity keeps emotional and symbolic ties to WCN alive in the case of Smedovac. When the distance is not too large, functional relations exist (case of Rogljevo and Rajac).

- Capacity of the local population to use and manage WCN. The age of population functions as a limiting factor, since it diminishes active use of WCN for wine production(the case of Smedovac).

- Motivation of the local population to use and manage WCN. Local people active attitude towards tourism development of WCN has been expressed in Rajac and Rogljevo and works as a motivation factor for active involvement in the presentation of CHS. Surprisingly, although not using WCN for wine production anymore, people in Smedovac have strong emotional connections to place and expressed the will and motivation to support their revitalization and future management, while inhabitants of Štubik stayed passive.

4.5. Learning from WCN PUD Project

4.6. WCN PUD Project Quality Verification

The Relationship between Ename Charter Principles and WCN PUD Process and Projects

WCN PUD Projects’ Potentials and Limits to Accomplish Ename Charter Objectives of Interpretation and Presentation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Araoz, G.F. Preserving heritage places under a new paradigm. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (The Faro Convention). Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Fairclough, G.; Dragićević-Šešić, M.; Rogač-Mijatović, L.; Auclair, E.; Soini, K. The Faro Convention, a New Paradigm for Socially-and Culturally-Sustainable Heritage Action? Culture 2014, 1, 9–19. Available online: https://journals.cultcenter.net/index.php/culture/article/view/111 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- UNESCO; ICCROM; ICOMOS; IUCN. Managing Cultural World Heritage; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tunbridge, J.E.; Ashworth, G.J. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past As a Resource in Conflict; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- EnameCenter. Basic Guidelines for Cultural Heritage Professionals in the Use of Information Technologies—How Can ICT Support Cultural Heritage? Available online: http://www.enamecenter.org/files/documents/Know-how%20book%20on%20Cultural%20Heritage%20and%20ICT.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2145/ (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- CEMAT. European Rural Heritage Observation Guide—CEMAT. 2003. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806f7cc2 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Silberman, N.A. The ICOMOS–Ename Charter Initiative: Rethinking the Role of Heritage Interpretation in the 21st Century. Georg. Wright Forum 2006, 23, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. Negotiating Contestations for Community-Oriented Heritage Management: A Case Study of Loushang in China. Built Herit. 2019, 3, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- ICOMOS. Managing Tourism at Places of Heritage Significance. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/tourism_e.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- UNESCO. World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tourism/ (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- The World Conference on Sustainable Tourism. Charter for Sustainable Tourism. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Sustainable Tourism, Lanzarote, Canary Islands, Spain, 27–28 April 1995.

- International Conference on Responsible Tourism in Destinations. Declaration of Cape Town. Available online: https://responsibletourismpartnership.org/cape-town-declaration-on-responsible-tourism/ (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Australian Heritage Commission. Ask First: A Guide to Respecting Indigenous Heritage Places and Values. Available online: http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/ahc/publications/commission/books/ask-first.html (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Čolić, R.; Mojović, Đ.; Petković, M.; Čolić, N. Guide for Participation in Urban Development Planning; AMBERO: Belgrade, Serbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Avdoulos, E. Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia: Challenges of managing sacred places. In Personas y Comunidades: Actas del Segundo Congreso Internacional de Buenas Prácticas en Patrimonio Mundial; Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Servicio de Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 180–203. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, M.; MacLean, M.G.H.; Mason, R.; Myers, D. Heritage Values in Site Management: Four Case Studies; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2005; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/values_site_mgmnt (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Poulios, I. Moving Beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CITTA. Methodology for the Development of Management Plans for Urban World Heritage Sites; Faculty of Engineering of the University of Porto, CITTA Research Centre for Territory, Transports and Environment: Porto, Portugal, 2020; Available online: http://www.atlaswh.eu/files/publications/20_1.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Khirfan, L. World Heritage, Urban Design and Tourism—Three Cities in the Middle East; Ashgate: Surrey, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, A.; Watson, S. Community-based Heritage Management: A case study and agenda for research. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2000, 6, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, C.; Assumma, V. Role of Cultural Mapping within Local Development Processes: A Tool for the Integrated Enhancement of Rural Heritage. Adv. Eng. Forum 2014, 11, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moscardo, G. Mindful visitors: Creating sustainable links between heritage and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Lew, A.A. Tourism Geography: Critical Understandings of Place, Space and Experience, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, D. Literary Places, Tourism and The Heritage Experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberman, N.A. Process Not Product: The ICOMOS Ename Charter (2008) and the Practice of Heritage Stewardship. CRM J. Herit. Steward. 2009, 10. Available online: http://scholarworks.umass.edu/efsp_pub_articles/10 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Stewart, E.J.; Hayward, B.M.; Devlin, P.J.; Kirby, V.G. The “place” of interpretation: A new approach to the evaluation of interpretation. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaginova, I. Heritage Presentation: How Can It Enhance Management of the World Heritage Sites? VDM: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, H.W. Construction of Interpretation and Presentation System of Cultural Heritage Site: An Analysis of the Old City, Zuoying. Heritage 2021, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, M.; Drobnjak, B.; Kuletin-Ćulafić, I. The Possibilities of Preservation, Regeneration and Presentation of Industrial Heritage: The Case of Old Mint “A.D.” on Belgrade Riverfront. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Ename Charter—The Charter for the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 16th General Assembly, Québec, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Voogd, H. Marketing of Tourism Places: What Are We Doing? In Global Tourist Behaviour; Uysal, M., Ed.; The Haworth Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter, D.L.; Confer, J.J.; Graefe, A.R. An exploration of the specialization concept within the context of heritage tourism. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, J.; Milovanović-Rodić, D. Klimatski senzitivan dizajn javnih prostora kao faktor kvaliteta turističke destinacije (Climate-sensitive Public Space Design as a Quality Factor of Tourist Destination). In Savremeni Pristupi Urbanom Dizajnu za Održivi Turizam Srbije (Contemporary Approach to Urban Design for Sustainable Tourism of Serbia); Lalović, K., Radosavljević, U., Eds.; Faculty of Architecture of the University of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 2011; pp. 135–159. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/vernacular_e.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Battani-Dragoni, G. Editorial: The Rural Vernacular Habitat, a Heritage in Our Landscape. Futuropa 2008, 1, 3. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/090000168093e668 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Madanipour, A. Design of Urban Space: An Inquiry into a Sociospatial Process; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- ASBEC. Creating Places for People—An Urban Design Protocol for Australian Cities. Available online: https://urbandesign.org.au/content/uploads/2015/08/INFRA1219_MCU_R_SQUARE_URBAN_PROTOCOLS_1111_WEB_FA2.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2016).

- Carmona, M.; Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, D.; Steiner, F.R. Urban Ecological Design: A Process for Regenerative Places; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K.; Hack, G. Site Planning, 3rd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- McIndoe, G.; Chapman, R.; McDonald, C.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Sharpin, A.B. The Value of Urban Design—The Economic, Environmental and Social Benefits of Urban Design; Ministry for the Environment: Wellington, New Zealand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. Good City Form; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. A New Theory of Urban Design; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sanoff, H. Participatory Design: Theory and Techniques; Henry Sanoff: Raleigh, NC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, A. Assessment of the design participation school of thought. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2000, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Negotinske Pivnice. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5537/ (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Dul, J.; Hak, T. Case Study Methodology in Business Research; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodrick, D. Comparative Case Studies, Methodological Briefs: Impact Evaluation No. 9; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Emerald Publishing. How to Undertake Case Study Research. Available online: https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/archived/research/guides/methods/case_study.htm (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Đukanović, Z.; Cecchini, A.B. (Eds.) Wine Cellars of Negotin: Participatory Urban Design; Istituto Italiano di Cultura: Belgrade, Serbia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Municipality of Negotin. Sustainable Development Strategy of The Municipality of Negotin. Available online: https://soilprotection-bgrs.info/bazaznanja/eng/index.php/opsta-dokumenta/185-opsta-dokumenta/srbija/189-sustainable-development-strategy-of-the-municipality-of-negotin (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Tomašević, B. Negotinske pivnice, vrednosti, izazovi i turistički potencijali (Negotinske pivnice, values, challenges and tourist potential). In Etno Villages and Rural Ambient Units in Republic of Serbia and Republic of Srpska; Škorić, D., Ed.; Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018; pp. 85–99. Available online: http://dais.sanu.ac.rs/123456789/3301 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Alfirević, Đ. Customary rules of the Rajac wine cellars construction. Spatium 2011, 51, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfirević, Đ. Rajačke Pivnice: ZAŠTITA, Obnova i Razvoj—Metode Projektovanja u Kontekstu Zaštićene Celine (Rajac Wine Cellars: Protection, Restoration, Development—Design Methods in the Context of a Protected Environment); Orion Art: Beograd, Serbia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Štetić, S.; Pavlović, S.; Mihajlović, B.; Stanić, S. Wine Tourism as a Factor in the Revitalization of Rural Settlements Rajac and Rogljevo. Quaestus 2015, 6, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlović, S.; Belij, M.; Belij, J.; Ilinčić, M.; Mihajlović, B. Negotin wine region, then and now—the role of tourism in revitalising traditional winemaking. Anthropol. Noteb. 2016, 22, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Radosavljević, U.; Nedeljković, S.; Đjukanović, Z.; Bobić, A.; Milojkić, D.; Simić, I. Integralni Pristup u Održivom Razvoju Seoskog Turizma Istočne Srbije (Integrated Approach to Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism in Eastern Serbia); Arhitektonski fakultet Univerziteta u Beogradu: Beograd, Serbia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zaštita Kulturne Baštine Sela Rajac (Study of Cultural Monuments Protection in Rajac Village); Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of Serbia, Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of Niš: Beograd, Serbia, 2009.

- Studija Zaštite Graditeljskog Nasleđa na Prostoru Sela Rogljevo (Study of Protection of Building Heritage on the Territory of Rogljevo Village); Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of Serbia, Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of Niš: Beograd, Serbia, 2011.

- Djukanovic, Z.; Živković, J. VinoGrad. The Art of Wine; Faculty of Architecture University of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Živković, J.; Đukanović, Z.; Radosavljević, U. Urban Design Education for Placemaking: Learning From Experimental Educational Projects. In Keeping Up with Technologies to Create the Cognitive City; Vaništa-Lazarević, E., Krstić-Furundžić, A., Đukić, A., Vukmirović, M., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 114–137. [Google Scholar]

- Radosavljević, U.; Đorđević, A.; Živković, J.; Lalović, K.; Đukanović, Z. Educational projects for linking place branding and urban planning in Serbia. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1431–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đukanović, Z.; Živković, J.; Cecchini, A.; Beretić, N.; Plaisant, A.; Battaglini, E.; Giofrè, F.; Lalović, K. Towards Sustainable Regional Development Through Social Networking—“Negotinska Krajina” Case. In Proceedings of 4th International Academic Conference Places and Technologies 2017—Keeping up With Technologies in the Context of Urban and Rural Synergy, Arhitektonski Fakultet Univerziteta u Sarajevu, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 8–9 June 2017; Bijedić, Dž., Krstić-Furundžić, A., Zečević, M., Eds.; Arhitektonski Fakultet Univerziteta u Sarajevu: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017; pp. 312–322. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Existence, Space & Architecture; Studio Vista Limited: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt, R.A.; Rogers, P.R.; An, H. Protocols for Best Conservation Practice in Asia: Professional Guidelines for Assuring and Preserving the Authenticity of Heritage Sites in the Context of the Cultures of Asia; UNESCO Bangkok: Bangkok, Thailand, 2009; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000182617_eng (accessed on 22 July 2021).

| PUD Research Phases | Local Community (LC) Involvement—Actors | LC Participation Formats | LC Inputs to PUD Knowledge Base |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Preparation | Municipality representatives | Initiation, organization, discussion | Documentation: studies, plans, strategies |

| 2. Field research | Municipality level public, private, civic sector representatives Local level: commissioners, inhabitants | Public meetings and gatherings, guided torus by local commissioners, direct contact with locals: Data collection: survey, questionnaire, semi-structured interviews, in-situ guided tours | General: Social, economic and spatial problems and potentials at municipality and local level Specific: Stories and Places-information and values of specific WCN locations: potential resources and solutions for presentation |

| 3. Design | Municipality level public, private, civic sector representatives Local level: commissioners, inhabitants | Direct contact with local inhabitants Meeting with Municipality representatives | Additional specific information on locations Critical review of draft WCN PUD strategies and projects |

| 4. Presentation and verification | Municipality level public, private, civic sector representatives Local level: commissioners, inhabitants | Public exhibitions and discussion in Negotin, Rajac, Rogljevo, Stubik, Smedovac.. Survey | Critical review of draft WCN PUD strategies and projects |

| Local Community Knowledge | Urban Design Projects Reflecting LC Existential Space | CHS Presentation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input: Problems | Input: Potentials | Input: Stories | Input: Places | Theme Function | Location | Form | Formats and Character (Formal/Informal) | |

| Rajac | UD Strategy: Re-Connect | Formal/Informal | ||||||

| Infrastructure | Cultural heritage | Stories of celebrating and mourning | Scenic viewpoint | 1. | “Belvedere” – scenic viewpoint | Wine cellars,“In between” | Centre and place | Panels and signposts Lectures/Perform./Present Walking and guided tours |

| Lack of gathering places | Wine production(active) | “Hidden paths” between village - WCN | Paths | 2. | “Gathering place” | Wine cellars | Centre and place | Panels and signposts Displays Lectures/Perform./Present Walking and guided tours Activities for visitors |

| Local initiatives in tourism | “Popov kladenac” location | 3. | “Popov kladenac”(the priest’s well) | Village | Centre and place | Panels and signposts Lectures/Perform./Present Walking and guided tours | ||

| 4. | “Places in-between” | Wine cellars | Area and domains | “Living” Displays Activities for visitors | ||||

| Local identity | “Popov kladenac” (the priest’s well) story | Night ambiance /outdoor lighting | 5. | Path from Village to Wine cellars | “In between” | Directions and paths | Panels and signposts Walking and guided tours Activities for visitors | |

| 6. | Path to woods | “In between” | Directions and paths | Panels and signposts Walking and guided tours | ||||

| Local materials/pavement | 7. | Paths through Wine cellars | Wine cellars | Directions and paths | Panels and signposts “Living” Displays Walking and guided toursActivities for visitors | |||

| Rogljevo | UD Strategy: Sounds & Silence | Formal/Informal | ||||||

| Infrastructure | Cultural heritage | Stories of settlements for people and wine | Local materials/pavement | 1. | Path from Village to Wine cellars | “In between” | Directions and paths | Panels and signposts “Living” Displays Walking and guided tours Activities for visitors |

| Lack of gathering places | Wine production(active) | “sounds and silence” | Night ambiance /outdoor lighting | 2. | “Gathering place” | Wine cellars | Centre and place | Panels and signposts Displays Lectures/Perform./Present Walking and guided tours Activities for visitors |

| Local initiatives in tourism | Historic events | Memorial place | 3. | Memorial drinking fountain | Village | Centre and place | Panels and signposts Displays Walking and guided tours | |

| Local identity | 4. | “Places in-between” | Wine cellars | Area and domains | Panels and signposts Walking and guided tours | |||

| Štubik | UD Strategy: IN Between | Formal | ||||||

| Infrastructure | Cultural heritage | 1. | “Places in-between” | Wine cellars | Area and domains | Panels and signposts Lectures/Perform./Present Activities for visitors | ||

| Abandoned/ detached from locals | Recognised as potential by Municipality | / | / | |||||

| 2. | “Wetland” | Wine cellars | Directions and paths | Panels and signposts Walking and guided tours | ||||

| Smedovac | UD Strategy: RE + Youth, Wine, Dignity | Formal/Informal | ||||||

| 1. | Orchestration | Whole area | Area and domains | Panels and signposts Displays | ||||

| Infrastructure | Cultural heritage | Memories of: | School | |||||

| Large village, young people and school | Monument & gathering place | 2. | School and camp | Wine cellars | Area and domains | Lectures/Perform./Present Activities for visitors | ||

| Services | Local identity | Wine production | Wine street location | 3. | Drinking fountain and memorial | “In between” | Centre and place | Panels and signposts Lectures/Perform./Present Walking and guided tours |

| Depopulation | Enthusiasm and traditional knowledge | Historic events | Night ambiance /outdoor lighting | 4. | “Gathering place” | Wine cellars | Centre and place | Panels and signposts Lectures/Perform./Present Walking and guided tours Activities for visitors |

| Lack of gathering places | Drinking fountain location | 5. | “Wine street” | Wine cellars | Directions and paths | Panels and signposts “living” Displays Walking and guided tours | ||

| Local materials/ | 6. | Pavilions | Whole area | Centre and place | Displays | |||

| resources | 7. | Signposts | Whole area | Centre and place | Panels and signposts | |||

| No. | Principles (Ename) | WCN PUD Process | WCN PUD Projects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Access and Understanding | PUD process helps acquiring local knowledge for better understanding of WCN value and meanings. | PUD projects function as a support for different forms of interpretation and presentation programmes. They also aim to improve the physical condition of public spaces and their access, while at the same time contributing to memorable tourist experiences by revealing, highlighting or amplifying specific features and meanings of WCN as living heritage. Indirectly, they contribute to access and understanding of WCN by enhancing local communities’ quality of life and the environment as a prerequisite for protecting the traditional wine production and viticulture protection and presentation. |

| 2. | Information Sources | PUD process enabled gaining knowledge from different sources—scientific and living cultural traditions. | PUD projects managed to integrate local oral knowledge on places by interpreting them as elements of existential space, and following relations that exist between local people – WCN and landscapes. In locations where local participation enabled the formation of rich knowledge base and clear focus (Rajac, Rogljevo, Smedovac) it was possible to propose design strategies and project that enables a wide spectrum of presentation formats and infrastructures: panels, displays, lectures, walking and guided tours, places for activities and workshops. |

| 3. | Context and Setting | Involvement of local communities in PUD process helped reveal ways they establish their existential space. | Knowledge gained through participation of associated communities provided knowledge on how WCN relates to their wider social, cultural, historical and natural contexts and settings. This was further integrated into spatial strategies and projects of different kinds. Public space projects were designed to enable presentation of both tangible and intangible heritage of local communities. They also recognised the importance of a wider landscape for understanding viticulture and WCN and different kinds of scenic viewpoints were designed to highlight this relation. |

| 4. | Authenticity | The basic goal of PUD was to respect traditional social functions, and knowledge was gained through participation process. | Since the starting point of PUD project was to present WCN as living heritage site – protection of WCN fabric and values was of main importance. Formal conservation guidelines were strictly respected. In design projects, all visible interpretive infrastructures were designed as sensitive to the character, setting and the cultural and natural significance of the site. The use of local materials and elements of design was initiated and supported by local people. Locations for On-site concerts, dramatic performances, and other interpretive programmes were carefully planned to protect the significance and physical surroundings of the site. |

| 5. | Sustainability | PUD process helped reveal constraints for management and presentation. | PUD strategies and projects were conceptualised with sustainable development perspective in mind and based on specific spatial and social contexts. Presentation of WCN was conceptualised with a goal to support the local life of the place, which by itself becomes part of the presentation of WCN as a living heritage site. |

| 6. | Inclusiveness | Meaningful collaboration between academia, and local communities was achieved in PUD process. | Different ways of local communities’ participation helped better understanding of traditional rights and interests of property owners and host communities and their integration into urban design projects for presentation of WCN. |

| 7. | Research, Evaluation, and Training | PUD project is a continuation of previous collaboration between Negotin Municipality and UBFA. As such, it is an example of continuing research and learning for both partners. | The urban design projects are conceptualised as multifunctional and adaptable, wherever possible in order to be flexible for future revisions or expansion. Proposed projects are modest in their scope, taking into account economic constraints, but they are also based on the precautionary principle in order to be able to reflect and react to effects on the environment. |

| No. | Objectives of Interpretation and Presentation (Ename) | WCN PUD Project Potentials | WCN PUD Project Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Facilitate understanding and appreciation of cultural heritage sites and foster public awareness and engagement in the need for their protection and conservation | In PUD, different forms of local community participation in research and validation phases fostered public awareness, and contributed to better understanding, appreciation of WCN and future engagement of the local community. | Some additional value of the PUD could have been accomplished if the participation of local communities could have been organized in the form of design charrette. |

| 2. | Communicate the meaning of cultural heritage sites to a range of audiences through careful, documented recognition of significance, through accepted scientific and scholarly methods as well as from living cultural traditions | PUD project accomplished this goal through careful planning and realisation of different phases that enabled researchers to acquire different forms and ways of knowing, understanding and valuing WCN, in order to communicate authentic WCN meaning through urban design | PUD managed to test the quality of WCN presentation only as a design project. If any of the projects are delivered in the future, it will be an opportunity to validate the quality of communication of the WCN meaning to a range of audiences. |

| 3. | Safeguard the tangible and intangible values of cultural heritage sites in their natural and cultural settings and social contexts | Through different forms of participation in PUD research, different forms of knowledge was acquired that helps safeguard tangible and intangible values of WCN in their natural, social and cultural context. | Local spatial and social contexts, such in the case of Štubik village and WC, affect local communities’ involvement in participation through which specific knowledge about tangible and intangible values can be acquired and safeguarded. |

| 4. | Respect the authenticity of cultural heritage sites, by communicating the significance of their historic fabric and cultural values and protecting them from the adverse impact of intrusive interpretive infrastructure, visitor pressure, inaccurate or inappropriate interpretation. | Respect for the authenticity was one of the starting points in research that although following experts’ conservation guidelines aimed to involve local communities to participate in PUD in the situation when their heritage sites are to be presented. | PUD project time and organisational limits made it impossible to discuss authenticity in more detail with experts from the National Institute for Cultural Heritage. These shortcomings were managed through strict obedience of guidelines and plans (Rajac and Rogljevo) as well as with the application of Institutes methodology for places (Štubik and Smedovac) where studies and plans did not exist. |

| 5. | Contribute to the sustainable conservation of cultural heritage sites, through promoting public understanding of, and participation in, ongoing conservation efforts, ensuring long-term maintenance of the interpretive infrastructure and regular review of its interpretive contents. | With a main aim to “bring back hope to local people” PUD main goal was not only to enable quality presentation of WCN to tourists, but to help local recognise their place in management, interpretation and presentation of their heritage. This was achieved both through a UD process in which they were listened and respected and educated, but also through UD projects through which their stories of events and places were revealed and valued. | Wider discussion between stakeholders, not only from local, but also from regional and national level was not realised through PUD – but it would be important to organise it in order to reveal and harmonize different interests in WCN management as national CHS with potential to be WHS. |

| 6. | Encourage inclusiveness in the interpretation of cultural heritage sites, by facilitating the involvement of stakeholders and associated communities in the development and implementation of interpretive programmes. | PUD main goal was to encourage inclusiveness in the future management and interpretation of WCN – and therefore involved public, private and civic stakeholders in different forms and phases of the participative urban design process. | Inclusiveness was limited due to the specific rural context in which it is difficult to inform and organise associated communities to participate. This was partially managed through involving local commissioners. |

| 7. | Develop technical and professional guidelines for heritage interpretation and presentation, including technologies, research, and training. Such guidelines must be appropriate and sustainable in their social contexts. | This was not a part of PUD. | / |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Đukanović, Z.; Živković, J.; Radosavljević, U.; Lalović, K.; Jovanović, P. Participatory Urban Design for Touristic Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites: The Case of Negotinske Pivnice (Wine Cellars) in Serbia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810039

Đukanović Z, Živković J, Radosavljević U, Lalović K, Jovanović P. Participatory Urban Design for Touristic Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites: The Case of Negotinske Pivnice (Wine Cellars) in Serbia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810039

Chicago/Turabian StyleĐukanović, Zoran, Jelena Živković, Uroš Radosavljević, Ksenija Lalović, and Predrag Jovanović. 2021. "Participatory Urban Design for Touristic Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites: The Case of Negotinske Pivnice (Wine Cellars) in Serbia" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810039

APA StyleĐukanović, Z., Živković, J., Radosavljević, U., Lalović, K., & Jovanović, P. (2021). Participatory Urban Design for Touristic Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites: The Case of Negotinske Pivnice (Wine Cellars) in Serbia. Sustainability, 13(18), 10039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810039