1. Introduction

With strategies for sustainable investment, foundations in Germany should be able to bring together the funding aspects and asset sides of their work. Thanks to the twofold connection of charitable foundations with civil society and asset management, they have a major potential for leverage because they have to bring their capital into sync with the aims of their foundation [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In this context, innovative financing options such as crowdfunding are also emerging, which enable smaller foundations in particular to be more impact-oriented, linked to the foundation’s purpose [

5,

6]. But this rarely leads to an orientation towards sustainability in the investment strategies of foundations. This gives rise to the issues of which possibilities asset-investing employees envisage and where they experience constraints with regard to sustainable financial investment. Their position is not to be confused with programme managers who concentrate exclusively on spending money on projects concerned with foundations’ goals [

7], nor should it be confused with the top echelons of a foundation who are usually only concerned with the funding side.

The altered capital market landscape as a result of continuing low interest rates has clear consequences for foundations’ room for manoeuvre. Revenues have until now merely been regarded as a means to an end. Because of changed conditions on the capital market, however, asset investment is becoming an issue in its own right and the question of why revenues are going down has come under scrutiny [

1] (p. 32). Staff members responsible for investment strategy as a result assume a completely different profile within institutions. They are increasingly operating in a realm of conflicting priorities between expected returns and foundation goals. Because foundations are designed for perpetuity, they need as a matter of course to think long-term about capital investment, taking account of global and societal trends. The question of reputation arises in connection with this since the goals and capital holdings of charitable bodies are considered in tandem. In this way, areas of tension emerge between morality and profit, thereby giving rise to a discourse where before there was none.

Responsible employees therefore encounter the problem that they can only with difficulty assert their knowledge and experience of the moral as well as economic benefits of a sustainable financial investment policy. They have to initiate a new discourse within their foundation. This means re-negotiating the power to define fields of interest and action [

8]. This process is of course already active in civil society but is not yet prevalent within foundations. The social discourse on sustainable investment has to find its way into foundations in order to direct approaches to earning money besides the current one-sided focus on spending money on foundations’ goals by investing in social projects. This is an ongoing process that needs interest groups and allies in order to concentrate single discursive incidents into an accepted and influential position [

9]. The employees interviewed for this study are endeavouring to open up a new knowledge space that will involve a fresh orientation of activities and structures, and often feel helpless in their role as lone fighters within their foundations. They must engage in social interaction with colleagues and members of governing bodies such as, for example, executive or advisory boards, a board of trustees or expert committees. As initiators of discourse they thus act as sense givers.

The interpretation of patterns (frames) relating to sustainable investment available to employees responsible for assets was undertaken by way of qualitative interviews. Analysed on the basis of the framing approach, these give a picture of the obstacles but also pathways to rethinking financial investment activity (sense giving). With this focus, the present study serves as research into a discourse that has only recently emerged within the investment arms of foundations.

2. Literature Review on Foundations

Because the financial sector does not exist in isolation from the social realm but is rather a part of it, institutional investors are coming under increasing pressure to contribute towards environmental and climate protection. In 2018 the European Union published its Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth [

10] laying out recommendations for activities to finance the climate-related political goals enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement, as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), by redirecting the flow of capital. Sustainable investments complement the classic financial criteria with Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria. A distinction is made between various investment processes in the implementation, such as exclusion criteria, best-in-class, engagement or impact investment.

Crucial legislative reforms were enacted in 2000, 2002, 2007 and 2013 to encourage the growth of the foundation sector. Foundations should be set up as an active and vital pillar of civil society [

1] (pp. 18–19). But no research in Europe that deals with the implementation of such goals exists apart from in Switzerland, which has published a set of guidelines for foundations. Research on foundations is chiefly concerned with funding and the importance of foundations and charitable institutions to civil society. The complex processes of investing under today’s market conditions and the growing demand for sustainable investment has only recently started to become a research topic.

Studies of asset investment are another strand of research. Foundations need to observe two basic principles—assets must be productive and the foundation’s capital preserved. The core economic component of a foundation is the material basis for its business activity [

11] (p. 268). Investigations into asset management in the foundation context mainly concentrate on conditions imposed by legal frameworks and especially on legal restrictions set out in laws covering foundations and tax [

11,

12]. In the economic evaluation of sustainable capital investment, asset management as a means for achieving ends is increasingly the focus of this type of research. Investment strategies of foundations are mainly subject to quantitative inquiry, whereby strategies and measures of performance are analysed by way of simulation models [

13].

There are no official channels for gathering data about the amounts and patterns of assets held by German charitable bodies and foundations, and neither are there informative statistics regularly collected by associations. Occasional surveys are therefore an important source of data. According to the latest figures from the National Association of German Foundations, foundations in Germany have at their disposal capital worth at least €67.92 billion [

1] (p. 32). There is only limited information, on the basis of a few surveys, relating to the general distribution of foundations’ assets across various asset classes. According to the current and most up-to-date survey from 2017, 34.6 % of foundations hold their assets in fixed-interest securities, 11.9% in shares, 26.1% in property and 21.1% as cash reserves or fixed-term deposits [

14] (p. 43).

Sustainable financial investments by implication enable a foundation’s goals to be synchronised with the requirements of asset investment, because the attention paid to strategies of sustainable investment can not only be considered as policy guides for investment strategy in light of the social purposes of foundations, but also with an eye towards the principle of investing for profitability [

15]. At the same time, the issue of sustainability in the field of asset investment has taken on ever more importance over recent years. A meta-study that included over 2000 individual pieces of research indicates that the integration of sustainability criteria has had a positive impact on returns [

15]. Sustainability is mainstream, both in the social discourse around sustainable development and in the financial sector as ‘sustainable finance’ [

16,

17]. There are a number of initiatives at the national and international level [

18] that take into account stakeholders’ responsibilities and influence [

19,

20].

The aim of successful foundation management is to benefit society in accordance with the foundation’s charter. In terms of their long-term goals and the duty towards responsible corporate activities [

21], foundations also have a legal obligation to operate within the context of sustainability clause 80, paragraph 2 [

21]. Although 40% of the foundations surveyed stated that they would like to invest a proportion of their capital sustainably, with these types of survey only those foundations with a strong commitment to the future tend to be contacted. A response rate for this survey was a mere 38.9 % of the 437 initially contacted [

22].

The question of how decisions surrounding investment are made within foundations, and particularly of how sustainability criteria are reflected in this process, is one of discourse formation and the emergence of action-directed ways of thinking that cannot adequately be encapsulated in quantitative studies. Qualitative research is needed to explore interpretative frames and their structures and elaborations (through sense giving), and to understand how changes can occur and what obstacles to this change may exist. There is often a gap between the purpose of a foundation and a particular investment. The links between foundations’ goals and their investments has however been rarely researched. The investment of assets in sustainable capital instruments is principally of interest to foundations because this leads to the emergence of synergies between asset investment and the fulfilment of a foundation’s aims, whereby it is hoped that conflicts between financial management and fund allocation can be avoided. There has not to date been a study that grapples with discourses around sustainability within charitable bodies, so this study should therefore be viewed as exploratory. Its contribution lies in the awareness that the sustainability discourse has not yet reached the investment strategies of charitable foundations, not even of the big ones. And it shows how difficult it is for those who are in charge of such strategies to bring this discourse into their institutions.

3. Theoretical Basis and Research Question

This paper examines the process of sense giving on the part of ‘change agents’ (sense givers) responsible for foundations’ investments. As management leaders, they have the opportunity to steer the parameters of meaning within their organisations. Sense giving, in turn, describes the process of framing [

23]. Therefore this research uses the framing approach.

Sense giving and sense making are related phenomena, whereby the sense giver must first go through a process of constructing meaning in order to trigger in an audience the interpretative framework thus gained [

24]. In this depiction sense making and sense giving are instances of meaning creation and a realising of sense in practice which can be analysed by means of organisational processes of change in social interaction [

25]. This study will nevertheless focus on sense giving as an act of influencing or persuasion [

26]—that is, the initiation of a discourse.

Sense making describes the process by which individuals and organisations cope with complex environmental situations by jointly creating contexts of meaning [

27].

Sense giving is an interpretative process of constructing a new reality and actively influencing other actors in order to steer the sense making of other agents in a preferred direction [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The organisational reality and therefore the prevailing meanings in internal corporate discourse are decisively influenced via the framing produced by management [

32]. The sense giving process includes interpretations concerning new aims, which are generally passed down from top management echelons to those working at an organisation’s lower levels. These can appear, for example, in the form of consistent communication of a vision [

27].

As a theoretical basis, the concept of sense giving fits well with the methodological procedures and the claim of framing analysis: “sense giving is about framing” [

33] (p. 123), since “sense giving is a fundamental leadership activity” [

28]. Frames are interpretative frameworks that sense givers have shaped out of a preceding process of sense making, and which are put into effect by them in the exercising of a claim to leadership in an organisation. Actions, messages and utterances from management provide action-guiding attributions of value and meaning for sense making processes among staff, governing board members and stakeholders [

32]. They are thus interpretative frameworks that need to be negotiated in the interaction between sense givers and hierarchies, both internal and external to the enterprise [

34]. “[Framing] denotes an active, processual phenomenon that implies agency and contention at the level of reality construction. […] The resultant products of this framing activity are referred to as ‘collective action frames’” [

35] (p. 614).

The framing approach has established itself in research [

36] as a “new theoretical perspective” [

37]. It allows conclusions to be drawn regarding solution-oriented accounts and motives for action of participants in social movements. Foundation staff members tasked with investing assets are part of an established social movement because, when they advocate for sustainable development, they have built up for themselves frameworks of meaning that hark back to the environmental movement. In fact, every interviewee was in favour of sustainable development. All respondents positioned themselves in the context of the environmental movement, albeit to different degrees and at varying points in their careers. The findings from the present study afford insights into possibilities for, but also hindrances to, implementing orientations of value which are often encountered by people tasked with asset management who often feel themselves trapped in decisions as to what, where and indeed whether to invest. The reasons are clear to them as to why the sustainability movement’s strong potential for mobilisation comes to a halt in the operations of foundations and other charitable entities, and what changes are needed, in their view, to break through encrusted structures. In order to break through this crust, the Federal Association of German Foundations offers courses in a special foundation academy that increase the skills of the participants and thus contribute to professionalisation.

Social movements are often analysed with the aid of the framing approach—for example, movements against nuclear energy or for citizens’ or women’s rights [

38]. Foundation employees responsible for managing assets should thus be seen as actors who bring the principles of the movement into their foundation. The research questions that arise in this context in order to gain insights into established practice are: Which interpretative structures (frames) serve people as guiding convictions and how do they translate these into practice within their foundations (sense giving)? What pathways do they take and where do they see obstacles to implementing a sustainable investment strategy?

5. Findings and Reflections

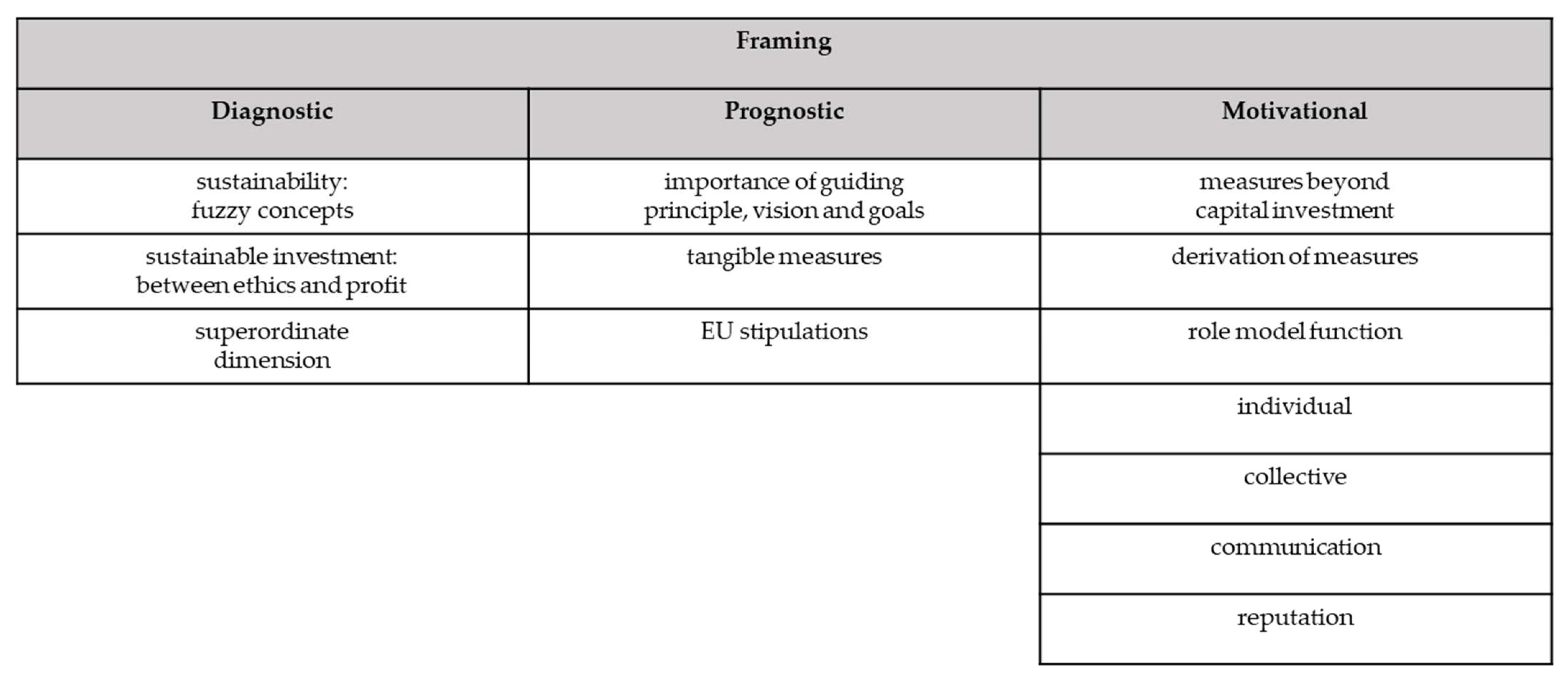

Diagnostic, prognostic and motivational categories are the framework for presenting the following findings. The framing structure of the asset-responsible foundation staff interviewed can be assessed with the aid of the following frames (

Figure 1), and this can highlight where sense givers see opportunities or obstacles to implementing sustainable investment.

The difference between small and large foundations, of relevance at times, should be noted at the beginning.

In smaller foundations, the attachment of old board members to their personal conception of the foundation’s goals manifests itself as an obstacle to the novel theme of sustainability. Many foundation staff, occupying positions on the governing board till they die, hang on to their extremely specific notions of the foundation’s goals. The admonition that the helm should be taken only by younger board members who have grown up within the discourse surrounding sustainability shows that it is not only personal convictions that present a serious hurdle, even when decision-making hierarchies are relatively indistinct and where decision-making pathways are short, but also the helplessness of the responsible actors (“There’s a new generation coming up—at least that’s what I hope—which is much more obliged to make sustainability a central theme. Well, I do hope so.”) Changes are therefore delegated to young decision-makers. It also became evident that in smaller foundations there is a basic lack of knowledge about business performance indicators since functions relating to this aspect tend to be carried out by volunteers.

On the other hand and in terms of their decision-making hierarchies, large foundations have a lot in common with the big companies that have in many cases established them. The predicament in those cases is one of structure and cumbersome decision-making procedures, as will be shown below.

5.1. Diagnostic Framing: Fuzzy Concepts, Encrusted Structures and Outdated Foundation Tenets

A diagnostic frame shows the underlying principles of a problem. This frame consists of three subcategories which focus on specific definitions, discussions on moral implications and on fundamental readjustments.

Fuzzy concepts and terminology surrounding the issue of sustainability is diagnosed by interview partners as a central problem as there is no single solution for sustainable investing. However, examination of the foundation’s own system of values is unavoidable, as external finance managers need clear instructions. Due to national differences there is a certain helplessness about what counts as exclusion criteria in the context of a strategy of sustainable investment. Nuclear energy, weapons, child labour and violations of human rights are crystallising as the market standard. A definition of exclusion criteria lays the groundwork for defining the scope of an investor’s value system. The interviews clearly showed that every foundation has to become aware of its own values—those that fit in with its goals—and this entails a complex and time-consuming process of discussion that turns out to be difficult to manage.

Under the subcategory sustainable investment: between ethics and profit, a clear tension is felt. Ethical conceptions are required in the effecting of exclusion criteria. Some cite a pragmatic relevance to financial return as the sole convincing argument for a change in thinking as sustainable investment relates to future-oriented technologies. They point to well-known studies that have established a positive correlation between profit and the integration of sustainability criteria. Some refer to the danger that the world of investment is being constrained by too many exclusion criteria and that performance ends up being sacrificed on this altar as a result. In this context, pros and cons of the lack of standards governing sustainable investment are discussed. The upside of labels is that clear criteria are set out, the disadvantage being that individual criteria for specific foundation goals can no longer be taken into account. This subcategory also reveals a certain helplessness when it comes to implementation so that only sustainable investment in the context of exclusion criteria and returns on investment are spoken about. Interviewees approach ethics and profit-orientation as two notions in conflict but they do not venture to tackle explicitly how to negotiate exclusion criteria specific to foundations. Whilst increasingly asset managers are successfully handling funds held by their institutions by means of sustainable strategies, discussions around exclusion criteria appear to be the greatest obstacle at the foundation level. The experts tended to interpret this as a hindrance to discussions that “go into every detail” or cause “disagreements”, pushing operationally necessary decisions down the road or even blocking implementation. This process in large foundations is costly and time-consuming, while one interview partner mentions that, in small foundations, decisions can be made more quickly and informally due to flat hierarchies. On the other side, small foundations suffer from having less personnel capacity so they can only resort to existing funds.

Interviewees point out, in terms of the superordinate dimension, that sustainability ultimately calls for innovative visions and readjustments, which would change the image of a foundation for the better in the eyes of benefactors. To cling onto exclusion criteria might therefore be a too much of a short cut. The experts are calling for role models, even though they are themselves seasoned financial market professionals. The idea of themselves assuming a role model function within their foundation seems—especially if that foundation is large—beyond their capacities. Their wish is for helpful entities from outside. Although most interviewees agree that foundations act to enhance the common good, the sustainability aspect is, due to the slowness of change, displaced to following generations. In the case of large-scale foundations with internal hierarchies focusing for example on funding or sponsorship, personnel or assets make an overall vision extremely difficult. In small foundations strategic readjustments can in contrast be quickly and informally decided upon and may therefore play a pioneering role in defining sustainability goals.

In diagnostic framing—that is, in the analysis of causes—the helplessness of actors is evident, making it obvious that many charitable entities do not regard sustainable investment as a new vision on top of their specific foundation goals, so that the interviewees need to initiate a wholly new discourse. Small foundations seem to be reaching a consensus more rapidly than larger bodies still caged by their own structural frameworks. It is astounding though that the simple profit argument is at the moment having little effect.

Fuzzy concepts, the age of the original establishers of foundations who concentrate on ‘their’ foundation’s goals in the context of institutional strategy and who oppose changes, and encrusted structures in large foundations seem to be the reasons for institutional inertia. This paints a picture of passivity and of being at the mercy of others. At least the agents in big foundations point to the need for role models and tangible sustainability labels, since complex discussions around criteria for exclusion seem to be hard to instigate.

Key findings of the diagnostic frame are obstacles to implementation through the existence of encrusted structures. Even though concepts relating to sustainability are still relatively fuzzy, every foundation has to become aware of its own value as a vehicle for achieving these ends. The discourse on sustainability needs to be promoted and encouraged. Although returns are used as an argument, discussions about sustainable investment are often emotional. There is a need for role models to showcase how the personal and economic benefits, to the wider public as well as to the foundations themselves, can be combined in the service of sustainable asset investment.

5.2. Prognostic Framing: A Call to Orientate, Labels, Role Models and Missing Tools

Prognostic framing functions in an intermediate position between defining a set of problems (diagnostic frame) and mobilising to address them (motivational frame). In the present study the frame consists of three subcategories (

Figure 1), involving an exposition of possible goals, instruments, strategies, and methods. Prognostic framing clarifies in the minds of actors what needs to be done to solve a problem. The interviews also aim to identify opportunities and obstacles that can be identified in establishing sustainable investment strategies.

Discussions relating to the first category importance of guiding principle, vision and goals focuses on how tangible investment criteria should be, and what else is required for introducing this new discourse. The pragmatic upside of rather unspecific visions is mentioned—for instance, with respect to investment guidelines, which in their legal formulation constitutes a parallel system of rules, since explicit sustainability criteria could change at the operational level with no requirement for these changes to be voted upon or agreed to at the board level. In contrast, one interviewee said that “sustainability should be materialised” in order to pass muster in front of overwhelmingly male-dominated committees, so that the emotional dimension is kept away from the topic. In the context of visions and strategic reorientation of investments, there was also the view that the presence of more women, similar to a younger foundation board profile, would somehow contribute to a different set of attitudes towards sustainability. Helplessness is also manifest here in a call for role models or ‘heroes’ who can relieve staff of the burden of fashioning a new discourse.

But others mentioned specific steps that should be taken. Some experts see the need to facilitate discussion so as to clarify in advance what the agents involved—from employees to committee members—view sustainability to entail. The difficulty of finding a consensus around sustainability criteria could be met with a ‘development thread’ in order to kickstart a process in stages by first steering one’s way towards the market standards and to further refine sustainability criteria that can be adapted to the foundation’s goals over time. The leadership level is also cited as a starting point for initiating and conveying a vision. Again, it becomes clear that sustainability has not yet been absorbed into the organisational culture of some foundations. Helplessness is evident in the lack of a suitable toolkit for strategy development and implementation. All experts emphasise that change can only be tackled in stages. However, there is uncertainty around where the starting point for this process should occur—with the foundation’s goals, with a guiding principle or mission statement, initially with operational questions or with the question of where a foundation currently stands—in order to develop a strategy.

The subcategory tangible measures refers to instruments, for example investment guidelines, which are commonly established in every financial institution to provide a framework for activities. As with the importance of strategies, tangible measures in the form of investment guidelines are mentioned several times as a basis that can be made use of in committees to provide a binding policy framework built on consensus. At the same time, techniques and methods would also need to be learnt for operational implementation to be enabled. Investment guidelines are however only effective if they are put into action, and this requires consensus. There was sometimes no clear distinction made between exclusion criteria and more far-reaching strategies. No consideration was given to whether, for example, the National Association of German Foundations could develop advisory services, instruments or strategies that could be offered to smaller members in particular.

Under the third category, European Union stipulations, interview partners focused on the strategic meta-level; that is, they made suggestions about which strategies could be set in place by the EU. Standardisation is discussed as being beneficial but also that it could lead to the risk of excessive regulation and costly auditing and these are deemed to limit the orienting of investment criteria that can be adapted to a foundation’s goals. The call for common standards and labels is a striking theme among experts and begs the question of individual definition, because even labels do not free employees from the responsibility for addressing the goals and concomitant investment criteria of their foundation. (“I still believe that there’s no other way than making rules”) Yet the call for recognised institutions to orientate themselves comes loud and clear, corresponds with the desire for role models to ease the burden and is again an expression of helplessness.

Prognostic framing as a means of pointing out solutions and of identifying strategies and tactics shows the need for instruments and strategic developments like investment guidelines or labels. In fact, over half of the foundations in Germany lack the fundamental instrument of the investment guideline. Interviewees are unanimous in their criticism that there is no willingness to develop policies that unite the goals of a foundation with its investment strategy. However, there are also deficits in technique with respect to possible approaches. Apart from that, no interview partner had specific ideas about how such a discourse could be launched within their foundation.

The key findings from prognostic framing are that change happens in stages, and that role models are therefore required to show stakeholders how they can advance their goals of investing sustainably. Tools like investment guidelines can provide a framework for this and can also help to reduce possible liability in future.

5.3. Motivational Framing: Lack of Toolkit and Hierarchy Entrapment

Motivational framing deals with the transmission to stakeholders of motivations to invest sustainably, in order to set out the benefits of this approach or to receive assurance from personal and organisational networks and reveal options for action. The interview partners present tangible motivations. The division into seven subcategories (

Figure 1) shows the complex ways in which foundation employees view their scope for action. There is a great deal of overlap here with diagnostic framing, since the interviewees are still occupied with identifying obstacles but rarely produce actionable options.

In terms of the subcategory measures beyond capital investment, the EU debate around taxation of carbon emissions is mentioned as a means to initiate new structures and internal discussions in order to ascertain the carbon footprint of each investment. This reference to external pressure as being necessary to induce internal reorientation is once again evidence that interviewees often feel insufficiently capable of acting in the face of inflexible hierarchies or foundation originators entrenched in their positions.

In the subcategory derivation of measures (with sustainability as the starting point), behavioural changes within every organisation but also in the personal sphere are mentioned, for example concerning travel preferences and patterns of consumption during work times which might help to create general awareness.

Under the subcategory role model function, the potential of small foundations to act as a role model for larger charitable bodies was addressed as a small foundation’s scope for investment is constrained by its limited resources of capital but, on the other hand, decisions can be more streamlined and strategies designed more easily (“Well, we, as small foundations, can act much more easily. Although we do have our restrictions, such as a rather small capital and number of projects. But I think we can show the bigger foundations, how we go about things—we can give them inspiration, can’t we?)”.

The most comprehensive subcategory concerns the individual. Five out of the eight interviewees mentioned the individual in terms of possible courses of action. The value systems of each individual within a charitable body hence play a leading role as he or she is generating and translating into action his or her own perspectives, thereby addressing both the sense making process and alluding to the importance of leaders—that is, sense givers—who should push through changes and put into practice appropriate conceptions of value. What is less understood here is the role of sense makers as embodiments of leadership, which is only vaguely sketched out. Options for action include appeals to make a decision as an individual agent in order to engender a consensus around exclusion criteria, or references to the pressure to act that can arise when interest rates are low. Such mentions remain, however, unspecific in terms of specific procedures. Interviewees express resignation that foundations lack the will to negotiate sustainability criteria. It is often the higher echelons that do not act, and the hierarchical nature of decision-making forms an especial obstacle.

To readjust a corporate culture is no easy process, as is seen in commercial companies where, for instance, agile teams are supposed to work across hierarchies. Here, too, a scarcity of help and orientation is referenced which characterises not just the standpoint of the sense giver but also describes the organisation as a whole. Hope for the requisite pressure from outside again indicates the desire not to have to initiate a new discourse, which for many actors is inconceivable.

The subcategory communication was mentioned as a crucial aspect by half the experts. They see the need to ensure that the governing board communicates competently by providing information around the issue of sustainability and investment strategies (“Well, and there I can only advise everybody to inform the steering committee in-depth, so that it really understands the topic being discussed”). External pressure is again referenced, for example due to periods of low interest rates. The conclusion to draw from this is that arguments can be put forward based solely on the bottom line. One interview partner sees the possibility of going on the offensive by communicating investment strategy to the public, for example in the annual report or on the foundation’s website. Foundations currently have no statutory obligations towards transparency or public disclosure. Proactive public communication would open up the opportunity to obtain donations or expand fundraising. This would ultimately be a way to use external actors, which would serve as a catalyst for change. A sense of resignation particularly prevails among actors from large-scale charitable bodies as often only superficial compromises can be achieved because the impulse for strategic decisions is the ‘tone from the top’. No substantive change will occur otherwise. This observation leads into the next category, since it covers the question of what could shake up the higher levels of the hierarchy if managers were to address the theme of sustainability.

The final subcategory looks at aspects surrounding reputation and the admonition not to belittle it. The outcomes of operational activities would need to be considered. To confront top echelons with risks to reputation, thereby producing emotions that would initiate changes, is pitted against the argument that it would be better to steer the topic towards improvements in performance rather than to ethical questions. This statement tallies with findings from the diagnostic frame: emotions overburden discussions around exclusion criteria with too much content relating to morality. One problem arising from this is that, in the case of foundations, moral considerations cannot be separated from rational ones regarding investment, and that investment criteria should represent foundation goals. It is argued that foundations must create their own landscape of values in order to avoid reputational risk.

Most subcategories appear as part of the motivational frame and this shows the amount of thought interviewees have given to this topic. Asset-responsible employees in foundations have ideas about achieving change and mention procedures for triggering motivation for action in the relevant governing committees. The task of the sense giver to take hold of the reins and spur on processes of change clearly comes across in their statements. It is important to hold superiors to account and to enhance communication. This frame also shows how foundation staff responsible for assets feel to a large extent trapped in hierarchies and cannot exercise the desired clout. They have to bring governing boards and executive committees along with them in their efforts at persuasion, which takes time and succeeds only to a limited degree. They may perhaps manage to put in place a partial strategy for asset management by relying on labels, kitemarks or agreed standards to reflect their basic tenets. However, an impact on the foundation as a whole cannot be definitively ascertained. In smaller-scale charitable bodies, those responsible for assets tend to be members of the governing board so the ‘tone from the top’ comes from a single source, such that the issue of sustainability is a total package of the foundation’s strategy across all departments. This makes many things easier. The main finding from the motivational frame is the requirement for a toolkit that sets out clearly the steps that foundations need to take to professionalise communication across several hierarchies or among different stakeholder.

6. Discussion

6.1. Main Findings and Contribution of This Research

The key conclusion to be drawn from this research is that charitable foundations need to realise that foundation-compliant investment has become an indispensable part of a foundation’s purpose. This knowledge is consistently lacking, regardless of the size of the foundation. People still act as if financing projects were the real task. On the financing side, only the weaving in of donations or the use of funding pots is seen. Sustainable forms of investment that would have to be adapted to the purposes of the foundation are nowadays indispensable. The contribution of the present research to the academic debate is to identify the obstacles that those responsible for investment encounter if they want to introduce such a social sustainability discourse in their foundations.

This study was carried out with qualitative methods because the aim was to explore people’s everyday practices and experiences in investing money in foundations with all the challenges and dilemmas this entails. This is not possible to a comparable depth with quantitative methods.

6.2. Trapped in Isolation

The experts interviewed are striving to introduce the social debate surrounding sustainability into the investment decisions of their foundations, but often contend with huge obstacles in doing so, because they are confronted with the task of galvanising a new internal discourse and are often, especially in large foundations, left to do this alone.

While many obstacles arise in the course of implementing policies, options for action remain largely indeterminate in the actors’ thinking. Many interviewees call for labels, role models, exemplars or ‘heroes’, by means of whom they hope either for external pressure to be applied on their organisations or for more interest in sustainability to somehow organically arise. These calls point to a certain hopelessness and thus to their dilemma of having few opportunities available to them to wield influence. Their prevailing attitude is one of resignation. In their isolation, they are overwhelmed by the task of establishing a new discourse. This set of problems is exacerbated by the fact that many governing board members as a rule lack the requisite financial knowledge, so that opening up a new discourse requires high hurdles to be cleared. Isolation is especially evident in large-scale and structurally complex foundations. Small foundations, on the other hand, have informal and short decision-making channels. Because these are mostly staffed by volunteers, however, the dearth of financial know-how and lack of resources for obtaining expert advice are particular stumbling blocks.

In terms of solutions, interviewees touched upon lines of argument taken with board members—for example, that guidelines covering sustainable investment can ultimately reduce liability or can enhance the foundation’s image with financial donors. The profitability argument is also strongly advanced. How they can reach the members of governing boards is, however, not made explicit. Interviewees are well aware that a straightforward discussion, particularly in large foundations, will hardly lead to success. Although they are devising possible ways to evolve investment criteria in order to stimulate the development of a vision of criteria for sustainability, hard-nosed financial arguments stand in opposition to a step-by-step process because, as sense givers, the interviewees need to be in contact with colleagues, governing committees and other foundation stakeholders. It is precisely in large foundations where their management tools for such a complex process are deficient.

Agents of change in large-scale charitable bodies especially suffer from isolation, whereas those in small foundations, by contrast, tend to become active themselves since hierarchies are flat. However, change agents in small foundations can face failure because the founders of these entities have first and foremost the specific goals of ‘their’ foundation in mind. It turns out nevertheless that devising tangible investment strategies is more realistic in small foundations.

Change agents responsible for assets need a targeted array of instruments—a toolkit—to steer communication and manage a change process. Whether detailed investment criteria are devised or foundations orientate themselves first towards standards that are easy to implement, the core challenge is to introduce this topic in the first place and thereby set in motion a more or less extensive strategic reorientation. This task appears to be too complex, especially for actors in large foundations.

The findings show above all that change agents strive as individuals to kickstart the required debate within their foundations instead of equipping themselves and building networks to this end. What is decisive is that they acknowledge their isolation in order to realise that, within their foundations, the direct path cannot be the first stage in inaugurating a discourse around sustainability. Rather, the communication tools and conflict resolution strategies of change management must first be acquired and networking, both inside and outside their foundations, is essential. A federal entity based in Berlin—the National Association of German Foundations—could provide targeted further training courses to offer change agents exactly those toolkits that protagonists lack. Networking events could also be organised to bring change agents together to exchange experience and best practice around this issue.

7. Outlook

The present study has addressed the question of how staff in foundations working in the realm of investment can stimulate strategies regarding sustainable investment. For this purpose, it examined their interpretative frames relating to awareness of sustainable investment.

The analysis of the interviewees’ interpretative frames has shown that they are faced, as change agents, with the task of bringing into foundations a sustainability discourse that is already far advanced in wider society. Sense makers’ scope for action is hindered by isolation, which is the case above all in large-scale charitable bodies as a consequence of their complex organisational structures. The call for salvation from outside (especially in large foundations) by means of EU guidelines and labels, but also role models and exemplary figures, cannot be ignored, whereas sense givers in small foundations tend to take a more active stance as they tend to work in flatter hierarchies. Although options for action were mentioned, with respect to large foundations these tend to remain rather vague where experts lack the requisite instruments, such as communication tools and conflict resolution strategies, to stimulate a wholly novel internal discourse. They must initially recognise their isolation. The first step is not to undertake hasty and sporadic forays within foundations but to accept that a fundamental process of change needs to be initiated that is too big a task for any one agent alone.

Further research should address more closely the isolation of change agents, especially in large foundations, and investigate suitable instruments for targeted processes of change for these bodies. Small foundations should be considered separately because structures in these cases tend to have less influence on strategic reorientations of investment strategy.