An Endless Endeavor: The Evolution and Challenges of Multi-Level Coastal Governance in the Global South

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

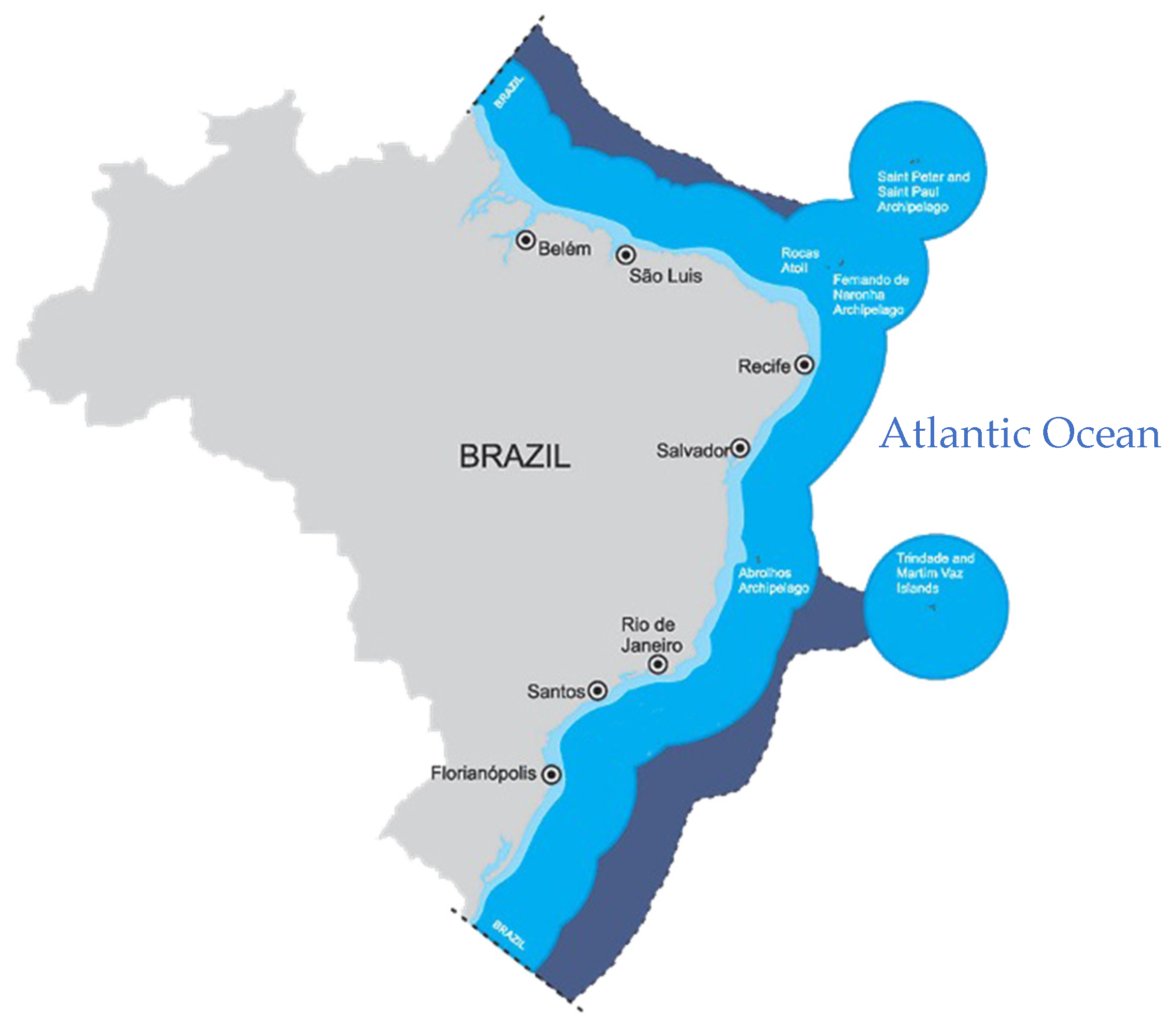

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Delving into Brazil’s Integrated Coastal Zone Management Policies

3.2. The Evolution of Twenty-Five Years of Coastal Management

- Period 1—the beginning of a new Era for coastal management (1996–2000)

- Period 2: Expansion of organizational forms and resistance to changes (2001–2012)

- Period 3—Homogeneity and Stability at conservation phase (2013–2016)

- Period 4—Stakeholder’s engagement at GIGERCO (2017–2018)

- Period 5—GIGERCO at a critical juncture (2019–2021)

4. An Endless Endeavor and an Opportunity for Future Transformation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Organizations Acronym | Full Name | Mandate | By 2018 | From 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SECIRM | Secretary of the Interministerial Commission for Sea Resources | Supports Navy to coordinate matters relating to the achievement of the National Policy for the Resources of the Sea (PNRM). | X | X |

| MMA | Environmental Ministry | Responsible for implementing the National Policy of Environmental and its deployments, such as the Coastal Management Plan, National System for Protected Areas, and others related to the coast and maritime zones. | X | X |

| MME | Energy and Mining Ministry | Oversees the gas and oil operation, as well as mining activities in the coastal areas. | X | X |

| ANAMMA | National Association of Municipalities of Environment | Civil entity, non-profit nor partisan, representative of the municipal government in the environmental area, with the objective of strengthening the Municipal Environment Systems to implement environmental policies, such as the municipal coastal management plans. | X | X |

| ABEMA/G17 | Brazilian Association of State Environmental Entities/Coastal State Integration Subgroup | Civil entity, non-profit nor partisan, representative of the state government in the environmental area, with the objective of strengthening the State Environment Systems to implement environmental policies, such as the state coastal management plans. And G-17 represents the 17 Brazilian coastal states. | X | X |

| IBAMA | Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources | It is the executive body responsible for the implementation of the National Environmental Policy and carries out various activities for enforcement and compliance of coastal and marine regulations, such as licensing. | X | X |

| MAPA | Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply | It is responsible for the management of public policies to stimulate agriculture and livestock. It houses the Fisheries Secretary, and hence it has the role to promote fisheries management. | ||

| MPF | Federal Prosecution Office | The MPF acts in federal cases, regulated by the Constitution and federal laws, whenever the issue involves public interest. For coastal areas, it works whenever an action to implement certain policies is requested. | X | X |

| Economy Ministry/SPU | Economy Ministry/Union Heritage Secretariat | It oversees budget planning. The Union Heritage Secretary authorizes the occupation of federal public real estate, establishing guidelines for free use, promotion, donation, or assignment when there is public interest. It is also responsible for the management of coastal territory and in control of the use of common goods of the people, among other duties. | X | X |

| Navy | Navy | Develops a comprehensive monitoring and control strategy for the protection of the coastal zone, as well as strengthens knowledge of the maritime environment and position available operational means to respond to any crises or emergencies in the Brazilian territorial sea. | X | X |

| MCTIC/MCTI | Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovations and Communications (by 2018)/Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovations (from 2019) | It collaborates with knowledge production and supports a variety of ocean observation systems for collection, quality control, operational distribution of oceanographic data, and oceanographic and climatological monitoring in the Southern and Tropical Atlantic Ocean. | X | X |

| MI | Infrastructure Ministry | It is responsible for national transit and transport policies, which include ports and marinas. | ||

| MDR | Regional Development Ministry | It has the role of implementing policies regarding sewage, coast protection, housing, and a variety of urban services. | X | |

| MTur | Tourism Ministry | It seeks to develop tourism as a self-sustaining economic activity in generating jobs and income. | X | |

| Civil Society/CONAMA | Civil Society—National Council of Environment | CONAMA may indicate environmental NGOs to occupy their seat on commissions, such as GIGERCO, and it normally mandates shifts depending on who is represented here. | X | X |

| Universities/PPGMAR | Universities | PPGMAR is a program to train human resources for the study of the sea and coast. It includes a variety of disciplines, and they are responsible for indicating the representatives of higher education and research institutions at GIGERCO. | X | X |

References

- Folke, C.; Pritchard, L.; Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Svedin, U. The Problem of Fit between Ecosystems and Institutions: Ten Years Later. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westley, F.R.; Tj, O.; Schultz, L.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Bodin, O.; Crona, B.; Tjornbo, O.; Schultz, L.; Olsson, P.; et al. A Theory of Transformative Agency in Linked Social-Ecological Systems E&S Home. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 24026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Romero, J.G.; Pressey, R.L.; Ban, N.C.; Vance-Borland, K.; Willer, C.; Klein, C.J.; Gaines, S.D. Integrated Land-Sea Conservation Planning: The Missing Links. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2011, 42, 381–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berkes, F. Evolution of Co-Management: Role of Knowledge Generation, Bridging Organizations and Social Learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehler, C.; Douvere, F. Marine Spatial Planning: A Step-by-Step Approach toward Ecosystem-Based Management. In Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and Man and the Biosphere Programme; Unesco: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 1–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenpagdee, R.; Pascual-Fernández, J.J.; Szeliánszky, E.; Luis Alegret, J.; Fraga, J.; Jentoft, S. Marine Protected Areas: Re-Thinking Their Inception. Mar. Policy 2013, 39, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.D.; Charles, A.; Stephenson, R.L. Key Principles of Marine Ecosystem-Based Management. Mar. Policy 2015, 57, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmus, M.L.; Nicolodi, J.; Eymael, M.; Scherer, G.; Gianuca, K.; Costa, J.C.; Goersch, L.; Hallal, G.; Victor, K.D.; Washington, L.; et al. Simples Para Ser Útil: Base Ecossistêmica Para o Gerenciamento Costeiro Simple to Be Useful: Ecosystem Base for Coastal Management Gerenciamento Costeiro a Um Contexto de Gestão. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 2018, 44, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halpern, B.S.; McLeod, K.L.; Rosenberg, A.A.; Crowder, L.B. Managing for Cumulative Impacts in Ecosystem-Based Management through Ocean Zoning. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Moore, M.L.; Westley, F.R.; McCarthy, D.D.P. The Concept of the Anthropocene as a Game-Changer: A New Context for Social Innovation and Transformations to Sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westley, F.; Antadze, N. Making a Difference Strategies for Scaling Social Innovation for Greater Impact FRANCES. Innov. J. Public Sect. Innov. J. 2010, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Galaz, V.; Olsson, P.; Hahn, T.; Folke, C. The problem of fit among biophysical systems, environmental and resource regimes, and broader governance systems: Insights and emerging challenges. In Institutions and Environmental Change: Principal Findings, Applications, and Research Frontiers; MIT Press Series; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; p. 371. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.H.; Abel, N.; Anderies, J.M.; Ryan, P. Resilience, Adaptability, and Transformability in the Goulburn-Broken Catchment, Australia. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.B.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Swilling, M.; Allison, E.H.; Österblom, H.; Gelcich, S.; Mbatha, P. A Transition to Sustainable Ocean Governance. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.C. Sustainability Science: A Room of Its Own. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1737–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Young, O.R. Governing Complex Systems: Social Capital for the Anthropocene, 1st ed.; MIT Press Series; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Mooney, H.; Hull, V.; Davis, S.J.; Gaskell, J.; Hertel, T.; Lubchenco, J.; Seto, K.C.; Gleick, P.; Kremen, C.; et al. Systems Integration for Global Sustainability. Science 2015, 347, 6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonçalves, L.R.; Oliveira, M.; Turra, A. Assessing the Complexity of Social-Ecological Systems: Taking Stock of the Cross-Scale Dependence. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J. Toward a “just” Sustainability? Continuum 2008, 22, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Aprova a Listagem Atualizada Dos Municípios Abrangidos Pela Faixa Terrestre Da Zona Costeira Brasileira; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2021; pp. 1–2.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Constituição Da República Federativa Do Brasil De 1988 Presidência Da República; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 1988.

- Jablonski, S.; Filet, M. Coastal Management in Brazil—A Political Riddle. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2008, 51, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardinger, L.C.; Gorris, P.; Gonçalves, L.R.; Herbst, D.F.; Vila-Nova, D.A.; de Carvalho, F.G.; Glaser, M.; Zondervan, R.; Glavovic, B.C. Healing Brazil’s Blue Amazon: The Role of Knowledge Networks in Nurturing Cross-Scale Transformations at the Frontlines of Ocean Sustainability. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 4, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polette, M.; Marenzi, R.; Turra, A. As mudanças do brasil nestes 25 anos do Plano Nacional de Gerenciamento Costeiro. In Os 25 Anos Do Gerenciamento Costeiro No Brasil: Plano Nacional De Gerenciamento Costeiro (PNGC); Ministério do Meio Ambiente: Brasília, Brazil, 2014; p. 181. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, S.N.; Menezes-Filho, N. Opportunistic and Partisan Election Cycles in Brazil: New Evidence at the Municipal Level. Public Choice 2011, 148, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, E.; Gonçalves, V.K. Brazil Ups and Downs in Global Environmental Governance in the 21st Century. Rev. Bras. Politica Int. 2019, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polette, M.; Freire Vieira, P.H. Avaliação Do Processo de Gerenciamento Costeiro No Brasil: Bases Para Discussão; UFSC: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2005; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Wever, L.; Glaser, M.; Gorris, P.; Ferrol-Schulte, D. Decentralization and Participation in Integrated Coastal Management: Policy Lessons from Brazil and Indonesia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2012, 66, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnside, P.M. Brazilian Politics Threaten Environmental Policies. Science 2016, 80, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, L.R. The Role of Brazil in the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (Iccat); RBPI: Brasília, Brazil, 2019; Volume 62, ISBN 0034732920190. [Google Scholar]

- Klumb-Oliveira, L.A.; Souto, R.D. Integrated Coastal Management in Brazil: Analysis of the National Coastal Management Plan and Selected Tools Based on International Standards. Rev. Gestão Costeira Integr. 2015, 15, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J.; Silver, J.; Evans, L.; Armitage, D.; Bennett, N.J.; Moore, M.L.; Morrison, T.H.; Brown, K. The Dark Side of Transformation: Latent Risks in Contemporary Sustainability Discourse. Antipode 2018, 50, 1206–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S.; Kofinas, G.P.; Folke, C. Principles of Ecosystem Stewardship: Resilience-Based Natural Resource Management in a Changing World; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, B.C.; Garmestani, A.S.; Gunderson, L.H.; Benson, M.H.; Angeler, D.G.; Tony, C.A.; Cosens, B.; Craig, R.K.; Ruhl, J.B.; Allen, C.R. Transformative Environmental Governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holling, C.S. The resilience of terrestrial ecosystems: Local surprise and global change. In Sustainable Development of the Biosphere; Clark, W.C., Munn, R.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986; p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- Dorado, S. Institutional Entrepreneurship, Partaking, and Convening. Organ. Stud. 2005, 26, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroni, E.V.; Asmus, M.L. Historical Antecedents and Local Governance in the Process of Public Policies Building for Coastal Zone of Brazil. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 76, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, M.E.G.; Asmus, M.L. Ecosystem-Based Knowledge and Management as a Tool for Integrated Coastal and Ocean Management: A Brazilian Initiative. J. Coast. Res. 2016, 75, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolodi, J.L.; Asmus, M.; Turra, A.; Polette, M. Evaluation of Coastal Ecological-Economic Zoning (ZEEC) in Brazil: Methodological Proposal. Desenvolv. Meio Ambiente 2018, 44, 378–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- dos Santos, C.R.; Polette, M.; Vieira, R.S. Gestão e Governança Costeira No Brasil: O Papel Do Grupo de Integração Do Gerenciamento Costeiro (Gi-Gerco) e Sua Relação Com O Plano de Ação Federal (PAF) de Gestão Da Zona Costeira. Rev. Costas 2019, 1, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.T.; Whiteway, T. Global Distribution of Large Submarine Canyons: Geomorphic Differences between Active and Passive Continental Margins. Mar. Geol. 2011, 285, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes, R.C.M.; Castro, C.B.; Pires, D.O.; Seoane, J.C.S. Depth and Water Mass Zonation and Species Associations of Cold-Water Octocoral and Stony Coral Communities in the Southwestern Atlantic. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 397, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sumida, P.Y.G.; Bernardino, A.F.; de Léo, F.C. Brazilian Deep-Sea Biodiversity; Springer International Publishing AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Mello BaezAlmada, G.V.; Bernardino, A.F. Conservation of Deep-Sea Ecosystems within Offshore Oil Fields on the Brazilian Margin, SW Atlantic. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente (MMA). Biodiversidade Brasileira: Avaliação e Identificação de Áreas Prioritárias Para Conservação, Utilização Sustentável e Repartição de Benefícios Da Biodiversidade Brasileira; MMA: Brasilia, Brazil, 2002.

- Wiesebron, M. Blue Amazon: Thinking about the Defense of the Maritime Territory. Aust. Braz. J. Strategy Int. Relat. 2013, 2, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.P. Brazil’s Recent Agenda on the Sea and the South Atlantic Contemporary Scenario. Mar. Policy 2017, 85, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros-Platiau, A.F.; Søndergaard, N.; Prantl, J. Policy Networks in Global Environmental Governance: Connecting the Blue Amazon to Antarctica and the Biodiversity beyond National Jurisdiction (Bbnj) Agendas. Rev. Bras. Politica Int. 2019, 62, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Cria a Comissão Interministerial Para Os Recursos Do Mar (CIRM) e Dá Outras Providências; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 1974.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Extingue e Estabelece Diretrizes, Regras e Limitações Para Colegiados Da Administração Pública Federal; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2019.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Aprova o X Plano Setorial Para Os Recursos Do Mar; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2020.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Dispõe Sobre a Comissão Interministerial Para Os Recursos Do Mar; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2019.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Aprova a Política Nacional Para Os Recursos Do Mar—PNRM; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2005.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Institui o Plano Nacional de Gerenciamento Costeiro e Dá Outras Providências; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 1988.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Regulamenta a Lei No 7.661/88, Que Institui o Plano Nacional de Gerenciamento Costeiro; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2004.

- Scherer, M.; Sanches, M.; de Negreiros, D.H. Gestão das zonas costeiras e as políticas públicas no Brasil: Um diagnóstico. In Manejo Costero Integrado y Política Pública en Iberoamérica: Un diagnóstico. Necesidad de Cambio; Barragán Muñoz, J.M., Ed.; Red IBERMAR: Cádiz, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Estabelece a Composição, as Competências e a Forma de Atuação Do GIGERCO; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2019.

- Gerhardinger, L.C.; Quesada-Silva, M.; Gonçalves, L.R.; Turra, A. Unveiling the Genesis of a Marine Spatial Planning Arena in Brazil. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 179, 104825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente (MMA). Primeiro Plano de Ação Federal Para a Zona Costeira; MMA: Brasília, Brazail, 1998.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Cria o Grupo de Integração Do Gerenciamento Costeiro; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 1996.

- Comissão Interministerial para Recursos do Mar (CIRM). Proceedings of the Ata Da Comissão Interministerial Para Os Recursos Do Mar. Grupo De Integração Do Gerenciamento Costeiro—Gi-Gerco-2-SESSÃO ORDINÁRIA, Brasília, Brazil, 24 April 1997.

- Comissão Interministerial para Recursos do Mar (CIRM). Proceedings of the Ata Da Comissão Interministerial Para Os Recursos Do Mar. Grupo De Integração Do Gerenciamento Costeiro—Gi-Gerco, Brasília, Brazil, 12 December 1997.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Dispõe Sobre a Política Nacional Do Meio Ambiente, Seus Fins e Mecanismos de Formulação e Aplicação, e Dá Outras Providências; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 1981.

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente (MMA). 2o Macrodiagnóstico Da Zona Costeira e Marinha Do Brasil; MMA: Brasília, Brazail, 2008.

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente (MMA). 1o Macrodiagnóstico Da Zona Costeira e Marinha Do Brasil; MMA: Brasília, Brazail, 1996.

- Comissão Interministerial para Recursos do Mar (CIRM). Ata Da 30a Sessão Ordinária Do Grupo De Integração Do Gerenciamento Costeiro (Gi-Gerco); CIRM: Brasília, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, L.; Holling, C.S. Panarchy Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; ISBN 9789004310087. [Google Scholar]

- Comissão Interministerial para Recursos do Mar (CIRM). Ata Da 51a Sessão Ordinária Do Grupo De Integração Do Gerenciamento Costeiro (Gi-Gerco); CIRM: Brasília, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente (MMA). Terceiro Plano de Ação Federal Para a Zona Costeira; MMA: Brasília, Brazail, 2014.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Institui Os Grupos Técnicos Para Assessoramento Da CIRM; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2019.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Revoga Portarias; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2020.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Altera o Decreto N 99.274, de 6 de Junho de 1990, Para Dispor Sobre a Composição e o Funcionamento Do Conselho Nacional Do Meio Ambiente—Conama; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2019.

- Governo Federal do Brasil. Resultado Do Sorteio de Que Trata o §10 Do Artigo 5o Do Decreto N. 99.274, de 6 de Junho de 1990, Para a Composição Da Representação Das Entidades Ambientalistas Do CONAMA; Governo Federal do Brasil: Brasilia, Brazil, 2021.

- Gelcich, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Defeo, O.; Fernández, M.; Foale, S.; Gunderson, L.H.; Rodríguez-Sickert, C.; Scheffer, M.; et al. Navigating Transformations in Governance of Chilean Marine Coastal Resources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16794–16799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nicolodi, J.L.; Asmus, M.L.; Polette, M.; Turra, A.; Seifert, C.A.; Stori, F.T.; Shinoda, D.C.; Mazzer, A.; de Souza, V.A.; Gonçalves, R.K. Critical Gaps in the Implementation of Coastal Ecological and Economic Zoning Persist after 30 Years of the Brazilian Coastal Management Policy. Mar. Policy 2021, 128, 104470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stori, F.T.; Shinoda, D.C.; Turra, A. Sewing a Blue Patchwork: An Analysis of Marine Policies Implementation in the Southeast of Brazil. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 168, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, M.M.; Berenguer, E.; Argollo de Menezes, M.; Viveiros de Castro, E.B.; Pugliese de Siqueira, L.; Rita de Cássia, Q.P. The COVID-19 Pandemic as an Opportunity to Weaken Environmental Protection in Brazil. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 255, 108994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, A.A.; Gerhardinger, L.C.; Madalosso, S.; Faroni-Perez, L.; Kefalas, H.C.; da Guarda, A.B. Mandato Coletivo: Atuação Inter-Redes Em Políticas Públicas Na Interface Com A Zona Costeira E Marinha Brasileira. In I Relatório do Programa Horizonte Oceânico Brasileiro: Ampliando o Horizonte da Governança Inclusiva para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável do Oceano Brasileiro; Horizonte Oceânico Brasileiro: Vitoria, Brazil, 2020; p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Young, O.R.; Webster, D.G.; Cox, M.E.; Raakjær, J.; Øfjord, L. Moving beyond Panaceas in Fisheries Governance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 2018, 115, 9065–9073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Phases of Change in Complex Adaptive Systems [35] | Definition |

|---|---|

| Exploitation | There is potential for the emergence of new institutions, with some degree of flexibility and predictability required for ambitious projects. The new norms and beliefs are not yet fully institutionalized but favor the development of new arrangements. |

| Conservation | Dominated by a few actors, homogeneity within actors and high stored capital—where actors may prefer stability and are inclined to resist change. |

| Release | Organizational forms are disaggregated, hence loosely connected to resources, hampering the ability to mobilize resources and the willingness to take risks necessary for social innovation. Share few organizational or institutional forms and often arise following a major political crisis, transitions or reforms. |

| Reorganization | New organizational forms and new linkages between actors emerge, creating opportunities for connecting ideas and resources strategically through various partnerships. Share in common a multiplicity and diversity of loosely coupled organizational forms. |

| Dimensions of Change | Categories | Definition | Type of Information (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of institutionalization (potential) | Stored Capital | A phase with stability and resistance to change. The accumulating potential could be from information, skills, networks of human relationships, and mutual trust. | GIGERCO report meetings neglecting pledges for more seats to environmental NGOs. |

| Released Capital | Shocks or crisis can lead individuals to question existing institutional arrangements and may promote change in the system, releasing resources for novel strategies or new actions. Resources can be material, cognitive or social. | Normative and legislation changes, such as CIRM and GIGERCO extinction and GIGERCO recreation Ordinance. | |

| Organizational forms (connectedness) | Homogeneity | Few actors. Loosely connected. Collaboration or patterns of conflict become so established and routine that the system becomes rigid/stable. | List of participants of GIGERCO meetings evidencing variety of goals proposed by different actors. GIGERCO meetings reports evidencing maintenance of issues Federal Action Plans indicating stability. |

| Heterogeneity | Various actors with more access to information resources. When those actors connect networks, organizations and/or individuals. Change in the system routine. | List of participants of GIGERCO meetings evidencing variety of goals proposed by different actors. Federal Action Plans evidencing variety of goals proposed by different actors |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonçalves, L.R.; Gerhardinger, L.C.; Polette, M.; Turra, A. An Endless Endeavor: The Evolution and Challenges of Multi-Level Coastal Governance in the Global South. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810413

Gonçalves LR, Gerhardinger LC, Polette M, Turra A. An Endless Endeavor: The Evolution and Challenges of Multi-Level Coastal Governance in the Global South. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810413

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonçalves, Leandra R., Leopoldo C. Gerhardinger, Marcus Polette, and Alexander Turra. 2021. "An Endless Endeavor: The Evolution and Challenges of Multi-Level Coastal Governance in the Global South" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810413

APA StyleGonçalves, L. R., Gerhardinger, L. C., Polette, M., & Turra, A. (2021). An Endless Endeavor: The Evolution and Challenges of Multi-Level Coastal Governance in the Global South. Sustainability, 13(18), 10413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810413