Organizational Justice and Leadership Behavior Orientation as Predictors of Employees Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Croatia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

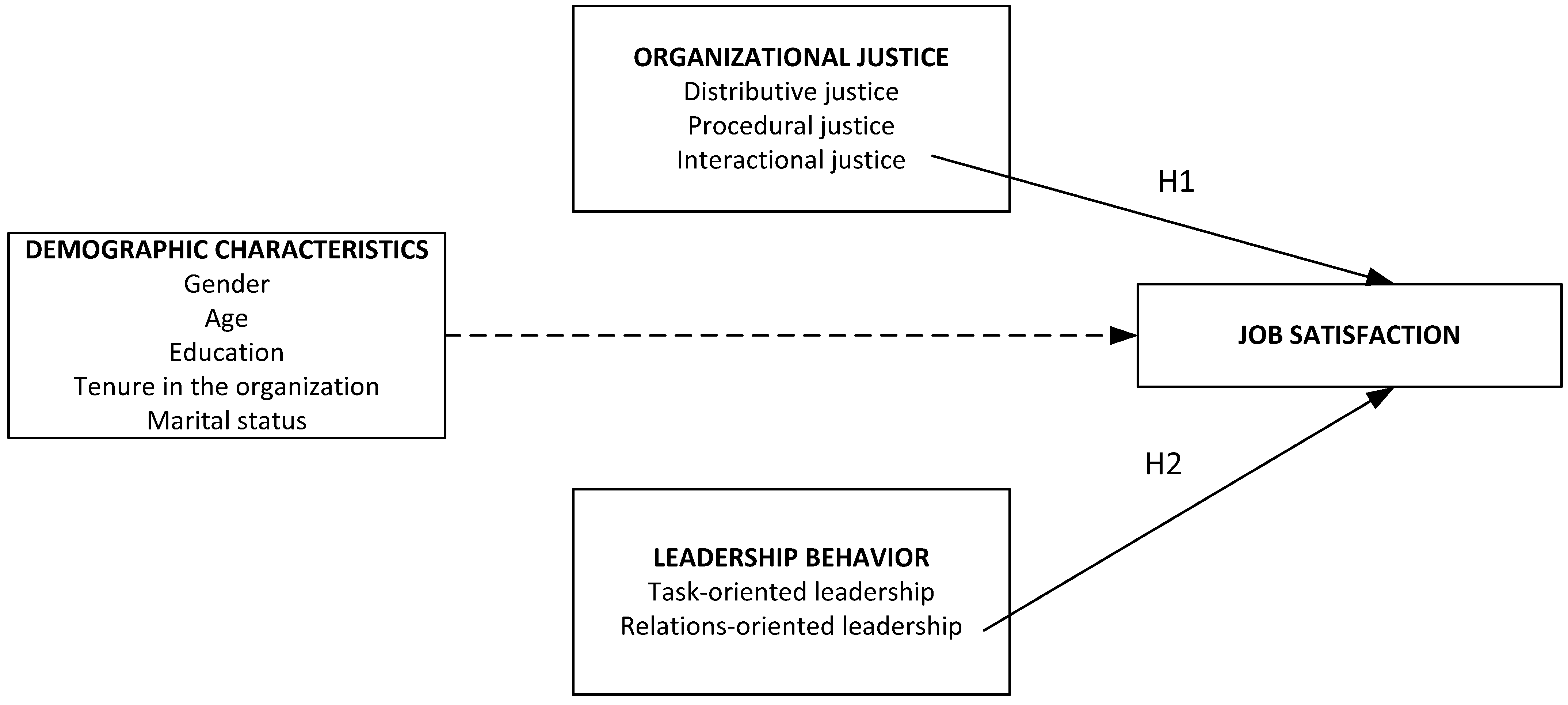

- Does organizational justice predict employees’ job satisfaction?

- Does leadership behavior orientation predict employees’ job satisfaction?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Job Satisfaction

2.2. Organizational Justice and Job Satisfaction

2.3. Leadership Behavior and Job Satisfaction

3. Methodology

3.1. Aim of the Research

3.2. Research Sample and Procedure

3.3. Research Instruments

3.4. Common Method Variance

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Research Results

5. Discussion, Implications and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Conclusions, Limitation and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dorta-Afonso, D.; González-De-La-Rosa, M.; García-Rodríguez, F.; Romero-Domínguez, L. Effects of High-Performance Work Systems (HPWS) on Hospitality Employees’ Outcomes through Their Organizational Commitment, Motivation, and Job Satisfaction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, A.N.A. Literature on The Relationships between Organizational Performance and Employee Job Satisfaction. Arch. Bus. Res. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Gursoy, D. Employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: An empirical examination. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Konstans, C.; Mashruwala, R. A Contextual Study of Links between Employee Satisfaction, Employee Turnover, Customer Satisfaction and Financial Performance; The University of Texas at Dallas: Dallas, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.R.; Raja, R. Employee Job Satisfaction and Business Performance: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment. Vision J. Bus. Perspect. 2021, 25, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, A.M. Perceived organizational justice and work-related attitudes: A study of Saudi employees. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 8, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Haque, M.; Elahi, F.; Miah, W. Impact of Organizational Justice on Employee Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Investigation. Am. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 4, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singhry, H.B. Perceptions of leader transformational justice and job satisfaction in public organizations. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2018, 14, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva, R.; Alegre, J. Emotional intelligence and job satisfaction: The role of organizational learning capability. Pers. Rev. 2008, 37, 680–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanchez-Manzanares, M.; Rico, R.; Antino, M.; Uitdewilligen, S. The Joint Effects of Leadership Style and Magnitude of the Disruption on Team Adaptation: A Longitudinal Experiment. Group Organ. Manag. 2020, 45, 836–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzgar, N. The Effect of Leaders’ Adoption of Task-Oriented or Relationship-Oriented Leadership Style on Leader-Member Exchange (LMX), In the Organizations That Are Active in Service Sector: A Research on Tourism Agencies. J. Bus. Adm. Res. 2018, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández, S. Examining the Effects of Leadership Behavior on Employee Perceptions of Performance and Job Satisfaction. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2008, 32, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zu’Bi, H.A. A Study of Relationship between Organizational Justice and Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, p102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liao-Holbrook, F. Integrating Leader Fairness and Leader-Member Exchange in Predicting Work Engagement: A Contingency Approach. Master’s Thesis, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokolo, E.; Ifeanacho, N.; Anazodo, N.N. Perceived Organizational Justice and Leadership styles as Predictors of Employee Engagement in the Organization. Nile J. Bus. Econ. 2017, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alamir, I.; Ayoubi, R.; Massoud, H.; Al Hallak, L. Transformational leadership, organizational justice and organizational outcomes. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwesigwa, R.; Tusiime, I.; Ssekiziyivu, B. Leadership styles, job satisfaction and organizational commitment among academic staff in public universities. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakotić, D. Relationship between job satisfaction and organisational performance. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2016, 29, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udovčić, A.; Požega, Ž.; Crnković, B. Analysis of leadership styles in Croatia. Ekon. Vjesn. Rev. Contemp. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Issues 2014, XXVII, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Miloloza, I. Analysis of the Leadership Style in Relation to the Characteristics of Croatian Enterprises. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst. 2018, 16, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakopec, A.; Sušanj, Z.; Stamenković, S. Uloga stila rukovođenja i organizacijske pravednosti u identifikaciji zaposlenika s organizacijom. Suvrem. Psihol. 2013, 16, 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Pomper, I.; Malbašić, I. Utjecaj transformacijskog vodstva na zadovoljstvo zaposlenika poslom i njihovu odanost organizaciji. Ekon. Pregl. 2016, 67, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, A.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Gerhart, B.A.R.R.Y.; Wright, P.M. Human Resource Management—Gaining a Competitive Advantage—International Edition, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill College: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla, J.; Djebarni, R.; Mellahi, K. Determinants of job satisfaction in the UAE: A case study of the Dubai police. Pers. Rev. 2011, 40, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamari, B. Changing management history, gender moderating pay to job satisfaction for IS users. J. Manag. Hist. 2014, 20, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafeshat, R.; Tanova, C. Servant Leadership Style and High-Performance Work System Practices: Pathway to a Sustainable Jordanian Airline Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Dorta-Afonso, D.; González-De-La-Rosa, M. Hospitality diversity management and job satisfaction: The mediating role of organizational commitment across individual differences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; De-Pablos-Heredero, M. A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study of Moderated Mediation between High-Performance Work Systems and Employee Job Satisfaction: The Role of Relational Coordination and Peer Justice Climate. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeleshi, J.; Dominic, T. Organizational Justice and Job Satisfaction among Different Employee Groups: The Mediating Role of Trust. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Razak, M.R.; Ali, E. Effect of Organizational Justice on Job Satisfaction in the Service Sector in Malaysia. Manag. Res. J. 2021, 10, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silitonga, N.; Novitasari, D.; Sutardi, D.; Sopa, A.; Asbari, M.; Yulia, Y.; Supono, J.; Fauji, A. The relationship oftransformational leadership, organizational justice and organizational commitment: A mediation effect of job satisfaction. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, S. The impact of manager and top management identification on the relationship between perceived organizational justice and change-oriented behavior. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2011, 32, 555–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.; Gallan, B.; Warren, A. Engaging creative communities in an industrial city setting: A question of enclosure. Gateways Int. J. Community Res. Engag. 2012, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen-Charash, Y.; Spector, P.E. The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 278–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folger, R.; Cropanzano, R. Fairness theory: Justice as accountability. Adv. Organ. Justice 2001, 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Härtel, C.; Azmat, F. Towards a diversity justice management model: Integrating organizational justice and diversity management. Soc. Responsib. J. 2013, 9, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenberg, J. Organizational justice: The dynamics of fairness in the workplace. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Volume 3, pp. 271–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazue, L.O.; Nwatu, O.H.; Ome, B.N. Relationship between Perceived Leadership Style, Organizational Justice and Work Alienation among Nigerian University Employees. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 18, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumari, A. National Culture and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Development of a Scale; Global Publishing House: Tamil Nadu, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Colquitt, J.A. Organizational Justice and Stress: The Mediating Role of Work-Family Conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mylona, E.; Mihail, D. Enhancing Employees’ Work Performance through Organizational Justice in the Context of Financial Crisis. A Study of the Greek Public Sector. Int. J. Public Adm. 2018, 42, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, D.L.; Sears, K.L.; Kelly, K.M. Work Engagement: The Roles of Organizational Justice and Leadership Style in Predicting Engagement among Employees. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2014, 21, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totawar, A.K.; Nambudiri, R.; Selvaraj, P. Justice, Satisfaction, Commitment: Mediation of Quality of Work Life and Psychological Capital. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2013, 2013, 15432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembiring, N.; Nimran, U.; Astuti, E.S.; Utami, H.N. The effects of emotional intelligence and organizational justice on job satisfaction, caring climate, and criminal investigation officers’ performance. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 28, 1113–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E.; Palazzeschi, L.; Di Fabio, A. How Can Organizational Justice Contribute to Job Satisfaction? A Chained Mediation Mode. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-R. An Empirical Study of Organizational Justice as a Mediator in the Relationships among Leader-Member Exchange and Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Turnover Intentions in the Lodging Industry. April 2000. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/27465 (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Zainalipour, H.; Fini, A.A.S.; Mirkamali, S.M. A study of relationship between organizational justice and job satisfaction among teachers in Bandar Abbas middle school. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 5, 1986–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosadeghrad, A.M.; Yarmohammadian, M.H. A study of relationship between managers’ leadership style and employees’ job satisfaction. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2006, 19, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saleem, H. The Impact of Leadership Styles on Job Satisfaction and Mediating Role of Perceived Organizational Politics. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yukl, G. Effective Leadership Behavior: What We Know and What Questions Need More Attention. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 26, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, B. Blending Constructs and Concepts: Development of Emerging Theories of Organizational Leadership and Their Relationship to Leadership Practices for Social Justice. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Prep. 2012, 7, n3. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ997470 (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Alonderiene, R.; Majauskaite, M. Leadership style and job satisfaction in higher education institutions. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016, 30, 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelson, A.C.; York, J.A.; Arritola, J. Communication Competence, Leadership Behaviors, and Employee Outcomes in Supervisor-Employee Relationships. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2015, 78, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research & Managerial Applications, Subsequent ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McMurray, A.; Pirola-Merlo, A.; Sarros, J.C.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, M. Leadership, climate, psychological capital, commitment, and wellbeing in a non-profit organization. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2010, 31, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.N.; Hua, N.T.A. The relationship between task-oriented leadership style, psychological capital, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: Evidence from Vietnamese small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2020, 17, 583–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleishman, E.A.; Harris, E.F. Patterns of leadership behavior related to employee grievances and turnover. Pers. Psychol. 1962, 15, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchen, M. Supervisory Methods and Group Performance Norms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1962, 7, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, A.; Griffin, M. Dimensions of transformational leadership: Conceptual and empirical extensions. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Lee, M. A study on relationship among leadership, organizational culture, the operation of learning organization and employees’ job satisfaction. Learn. Organ. 2007, 14, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sada, M.; Al-Esmael, B.; Faisal, M.N. Influence of organizational culture and leadership style on employee satisfaction, commitment and motivation in the educational sector in Qatar. EuroMed J. Bus. 2017, 12, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothfelder, K.; Ottenbacher, M.C.; Harrington, R.J. The impact of transformational, transactional and non-leadership styles on employee job satisfaction in the German hospitality industry. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2012, 12, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C. An Examination of the Correlation between Leadership Style and Job Satisfaction for Predicting Person-Organization Fit in Public Sector Organizations. Ph.D. Thesis, Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jakopec, A.; Sušanj, Z. Provjera dimenzionalnosti konstrukta pravednosti u organizacijskom kontekstu. Psihol. Teme 2014, 23, 305–325. [Google Scholar]

- Šehić, D.; Penava, S. Leadership; Univerzitet u Sarajevu, Ekonomski Fakultet: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pettijohn, C.E.; Pettijohn, L.S.; D’Amico, M. Characteristics of performance appraisals and their impact on sales force satisfaction. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2001, 12, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Zakaria, N. Relationship between Interactional Justice and Pay for Performance as an Antecedent of Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Study in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristic | Respondents | Job Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Mean | Range | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 173 | 60.1 | 3.59 | 1–5 |

| Female | 115 | 39.9 | 3.91 | 2–5 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–27 | 84 | 28.2 | 3.21 | 1–5 |

| 28–37 | 104 | 34.9 | 3.87 | 2–5 |

| 38–47 | 72 | 24.2 | 4.03 | 2–5 |

| 48–57 | 25 | 8.4 | 3.88 | 1–5 |

| 58–67 | 13 | 4.4 | 3.75 | 2–5 |

| Education | ||||

| Secondary education | 126 | 42.3 | 3.50 | 1–5 |

| College education | 38 | 12.8 | 3.70 | 2–5 |

| University education | 116 | 38.9 | 3.94 | 1–5 |

| Master’s degree or doctoral degree | 18 | 6.0 | 3.94 | 3–5 |

| Tenure in organization | ||||

| Less than 9 years | 191 | 64.5 | 3.60 | 1–5 |

| 10–19 | 74 | 25.0 | 4.01 | 2–5 |

| 20–29 | 19 | 6.4 | 3.84 | 3–5 |

| 30–39 | 10 | 3.4 | 3.63 | 1–5 |

| 40 and more | 2 | 0.7 | 3.50 | 3–4 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 127 | 42.6 | 3.44 | 1–5 |

| Married | 145 | 48.7 | 3.96 | 2–5 |

| Divorced | 21 | 7.0 | 3.70 | 1–5 |

| Widowed | 5 | 1.7 | 4.20 | 3–5 |

| Variables | Mean | Median | Mode | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction | 3.71 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.816 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 297 | |

| Organizational justice | Distributive | 3.31 | 3.60 | 4.00 | 0.931 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 298 |

| Procedural | 3.50 | 3.60 | 4.00 | 0.848 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 298 | |

| Interactional | 3.57 | 3.80 | 4.00 | 0.854 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 298 | |

| Leadership behavior orientation | Task-oriented | 3.80 | 3.90 | 4.00 | 0.675 | 1.40 | 5.00 | 298 |

| Relations-oriented | 3.66 | 3.75 | 4.00 | 0.692 | 1.50 | 5.00 | 298 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||||||

| 0.198 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 0.263 ** | 0.032 | 1 | ||||||||

| 0.251 ** | 0.328 ** | 0.082 | 1 | |||||||

| 0.239 ** | 0.089 | 0.531 ** | 0.166 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 0.101 | 0.026 | 0.722 ** | 0.009 | 0.478 ** | 1 | |||||

| 0.727 ** | 0.101 | 0.286 ** | 0.178 ** | 0.253 ** | 0.151 ** | 1 | ||||

| 0.681 ** | 0.129 * | 0.230 ** | 0.244 ** | 0.230 ** | 0.130 * | 0.770 ** | 1 | |||

| 0.720 ** | 130 * | 0.206 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.135 * | 0.787 ** | 0.847 ** | 1 | ||

| 0.582 ** | 0.061 | 0.181 ** | 0.196 ** | 0.173 ** | 0.072 | 0.608 ** | 0.675 ** | 0.704 ** | 1 | |

| 0.638 ** | 0.069 | 0.207 ** | 0.170 ** | 0.145 * | 0.101 | 0.653 ** | 0.666 ** | 0.721 ** | 0.869 ** | 1 |

| Predictor | β | R | R2 | ΔR | F | Collinearity Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||||||||

| 1. Step | Demographic variables | Gender | 0.126 * | 0.409 | 0.168 | 0.168 | 11.235 *** | 0.893 | 1.120 |

| Age | 0.330 *** | 0.449 | 2.225 | ||||||

| Education | 0.165 ** | 0.873 | 1.146 | ||||||

| Marital status | 0.125 | 0.675 | 1.482 | ||||||

| Tenure in the organization | −0.184 * | 0.473 | 2.114 | ||||||

| 2. Step | Demographic variables | Gender | 0.092 * | 0.890 | 1.123 | ||||

| Age | 0.142 * | 0.425 | 2.350 | ||||||

| Education | 0.038 | 0.831 | 1.204 | ||||||

| Marital status | 0.039 | 0.666 | 1.501 | ||||||

| Tenure in the organization | −0.156 ** | 0.466 | 2.147 | ||||||

| Organizational justice | Distributive justice | 0.327 *** | 0.786 | 0.617 | 0.450 | 108.184 *** | 0.308 | 3.249 | |

| Procedural justice | 0.076 | 0.244 | 4.096 | ||||||

| Interactional justice | 0.370 *** | 0.233 | 4.293 | ||||||

| 3. Step | Demographic variables | Gender | 0.092 * | 0.887 | 1.127 | ||||

| Age | 0.120 * | 0.420 | 2.378 | ||||||

| Education | 0.040 | 0.829 | 1.206 | ||||||

| Marital status | 0.067 | 0.647 | 1.546 | ||||||

| Tenure in the organization | −0.163 ** | 0.460 | 2.173 | ||||||

| Organizational justice | Distributive justice | 0.277 *** | 0.296 | 3.385 | |||||

| Procedural justice | 0.069 | 0.234 | 4.268 | ||||||

| Interactional justice | 0.304 *** | 0.211 | 4.734 | ||||||

| Leadership behavior orientation | Task-oriented leadership | −0.144 | 0.798 | 0.637 | 0.019 | 7.343 *** | 0.208 | 4.811 | |

| Relations-oriented leadership | 0.295 *** | 0.195 | 5.128 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakotić, D.; Bulog, I. Organizational Justice and Leadership Behavior Orientation as Predictors of Employees Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Croatia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910569

Bakotić D, Bulog I. Organizational Justice and Leadership Behavior Orientation as Predictors of Employees Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Croatia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910569

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakotić, Danica, and Ivana Bulog. 2021. "Organizational Justice and Leadership Behavior Orientation as Predictors of Employees Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Croatia" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910569