Hiring Disable People to Avoid Staff Turnover and Enhance Sustainability of Production

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainable Production

- resource efficiency (raw materials, energy, and water);

- clean energy and cleaner production;

- low emissions and climate-friendly solutions;

- responsible agriculture;

- chemical leasing;

- corporate social responsibility;

- stakeholder engagement.

1.2. Human Factor in Sustainable Production

- demographic and social changes (population growth, aging of the population; poverty, inequality, migration) with divergent global population trends (fertility, mortality)—education and solidarity;

- health management and cost pressures, changing disease burden and pandemic risks—healthy living, public health systems, and intensive research;

- rapid urbanization (megacities, mobility, security)—smart: cities, communities and homes;

- regional instability (public debts, crises, economic and financial shocks, migrations, conflicts and wars, danger of collapse)—more and more multi-circulation—new and intelligent world.

- social needs and values;

- organization and social behavior;

- social performance, responsibility, reputation;

- social value, social benefits (local, national, global);

- social justice, standard of living, quality of life;

- health and safety, working conditions, employment opportunities, education and training, community welfare;

- socioeconomic trends;

- politics, business strategy, business model.

1.3. Purpose of the Article

2. Materials and Methods

- Alternative hypothesis to H0:

- Alternative hypothesis to H0a:

3. Results and Discussion

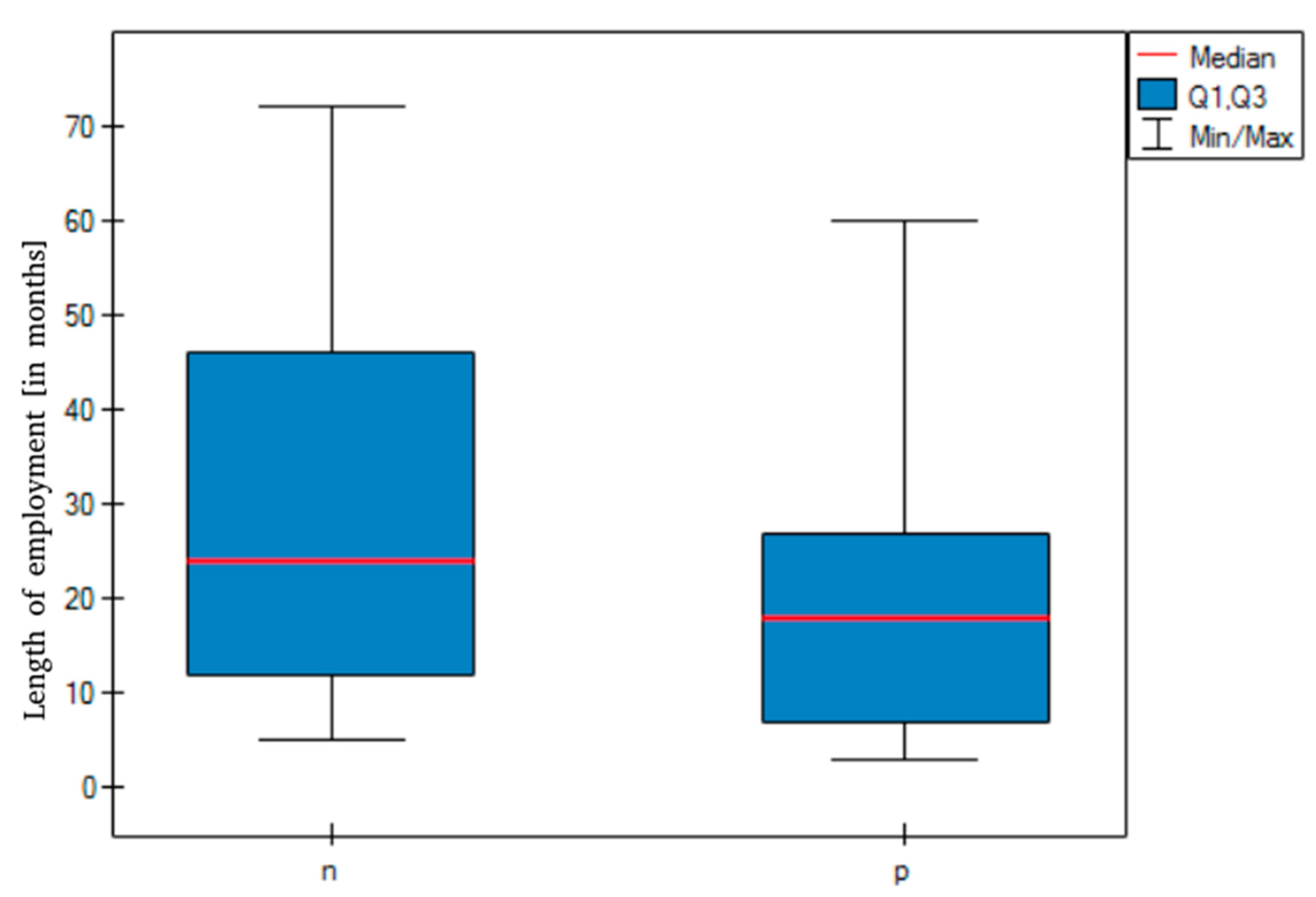

- the number of degrees of freedom equal to 9;

- significance level of p = 0.007.

- The significance level of the analysis is 0.05;

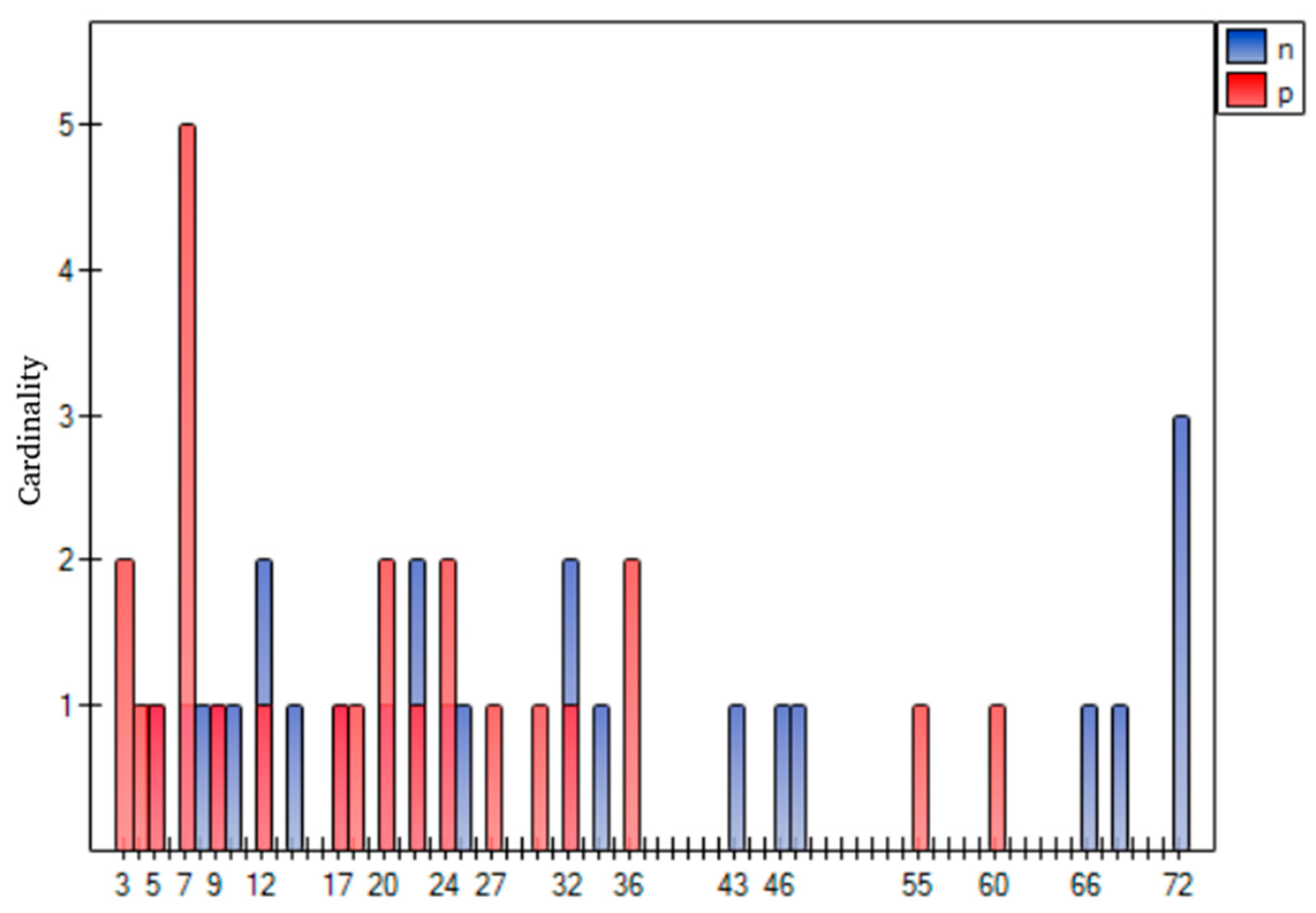

- The median time of employment for people with disabilities was 24 months;

- The median time employed for non-disabled people was 18 months;

- The exact p (two-tailed) test was 0.040588;

- The asymptotic (two-sided) p test was 0.041307.

- Alternative hypothesis to H0a:

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pagotto, E.L.; Gonçalves-Dias, S.L.F. Sustainable consumption and production from a strategic action field perspective. Ambiente Soc. 2020, 23, e00271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolis, I.; Morioka, S.N.; Sznelwar, L.I. When sustainable development risks losing its meaning. Delimiting the concept with a comprehensive literature review and a conceptual model. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 83, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perey, R. Making sense of sustainability through an individual interview narrative. J. Cult. Organ. 2015, 21, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska-Sałek, A. Managing a Sustainable Supply Chain-Statistical Analysis of Natural Resources in the Furniture Industry. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2021, 29, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vevela, V.; Ellenbecker, M. Indicators of sustainable production: Framework and methodology. J. Clean. Prod. 2001, 9, 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.; Nazam, M.; Abrar, M.; Hussain, Z.; Nazim, M.; Rizwan Shabbir, R. Unlocking the Sustainable Production Indicators: A Novel TESCO based Fuzzy AHP Approach. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1870807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Jahanzaib, M. Sustainable manufacturing—An overview and a conceptual framework for continuous transformation and competitiveness. Adv. Prod. Eng. Manag. 2018, 13, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.A.; Chomkhamsri, K. From Sustainable Production to Sustainable Consumption. In LCA Compendium—The Complete World of Life Cycle Assessment; Sonnemann, G., Margni, M., Eds.; Life Cycle Management; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Green Industry for a Low Carbon Future. Available online: http://www.unido.org/greenindustry/green-industry-initiative.html (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Glavič, P. Evolution and Current Challenges of Sustainable Consumption and Production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulewicz, R.; Kleszcz, D.; Ulewicz, M. Implementation of Lean Instruments in Ceramics Industries. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2021, 29, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R. The concept of operation and production control. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2021, 27, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, P.; Zolnieruk, M.; Oleszczyk, P.; Gisterek, I.; Kajdanowicz, T. Spatio-Temporal Profiling of Public Transport Delays Based on Large-Scale Vehicle Positioning Data From GPS in Wroclaw. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 3652–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baryshnikova, N.; Kiriliuk, O.; Klimecka-Tatar, D. Management approach on food export expansion in the conditions of limited internal demand. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 21, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimecka-Tatar, D. Analysis and improvement of business processes management—Based on value stream mapping (VSM) in manufacturing companies. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 23, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knop, K. Analysing the machines working time utilization for improvement purposes. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2021, 27, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardas, E.; Brožova, S.; Pustějovská, P.; Jursová, S. The Evaluation of Efficiency of the Use of Machine Working Time in the Industrial Company—Case Study. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2017, 25, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smirnova, E.; Kot, S.; Kolpak, E.; Shestak, V. Governmental support and renewable energy production: A cross-country review. Energy 2021, 230, 120903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendzel-Skowera, K. Circular Economy Business Models in the SME Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcz, J.; Ślusarczyk, B. Criteria of quality requirements deciding on choice of the logistic operator from a perspective of his customer and the end recipient of goods. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2021, 27, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowska, A.; Ingaldi, M. Application of Servqual and Servperf Methods to Assess the Quality of Teaching Services—Comparative Analysis. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 21, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadłubek, M.; Grabara, J. Customers’ expectations and experiences within chosen aspects of logistic customer service quality. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2015, 9, 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Klimecka-Tatar, D.; Nieciejewska, M. Small-sized enterprises management in the aspect of organizational culture. Rev. Gest. Tecnol.-J. Manag. Technol. 2021, 21, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepold, A.; Tanzer, N.; Bregenzer, A.; Jiménez, P. The Efficient Measurement of Job Satisfaction: Facet-Items versus Facet Scales. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ingaldi, M.; Ulewicz, R. Problems with the Implementation of Industry 4.0 in Enterprises from the SME Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niciejewska, M. Occupational health and safety management in terms of special employee needs—Case study. Syst. Saf. Hum.-Tech. Facil.-Environ. 2021, 3, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacz, M. The Professional Situation Od Disabled People on the Bieszczady Poviat. Syst. Saf. Hum.-Tech. Facil.-Environ. 2021, 3, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanck, P.; Adya, M.; Myhill, W.N.; Samant, D.; Chen, P. Employment of people with disabilities—Twenty-five years back and ahead. Minn. J. Law Inequal. 2007, 25, 323–353. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, J.L. Measuring autonomy in social security agencies: A four country comparison. Public Adm. Dev. SI Symp. Auton. Organ. Public Sect. 2004, 24, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R.; Skotnicka-Zasadzień, B. Developing a Model of Factors Influencing the Quality of Service for Disabled Customers in the Condition s of Sustainable Development, Illustrated by an Example of the Silesian Voivodeship Public Administration. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; University of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wysokość Dofinansowania do Wynagrodzeń Pracowników Niepełnosprawnych, Państwowy–Fundusz Rehabilitacji Osób Niepełnosprawnych. Available online: https://www.pfron.org.pl/pracodawcy/dofinansowanie-wynagrodzen/wysokosc-dofinansowania-do-wynagrodzen-pracownikow-niepelnosprawnych/ (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Rebernik, N.; Szajczyk, M.; Bahillo, A.; Goličnik Marušić, B. Measuring disability inclusion performance in cities using Disability Inclusion Evaluation Tool (DIE Tool). Sustainability 2020, 12, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- STATSOFT. Available online: https://www.statsoft.pl/Pelna-lista-programow-Statistica/?goto=statistica_enterprise#sc (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Herdan, G. The mathematical relation between Greenberg’s index of linguistic diversity and Yule’s characteristic. Biometrika 1958, 45, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PQStat Software. Available online: https://pqstat.pl/?mod_f=usersm (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Nachar, N. The Mann-Whitney U: A test for assessing whether two independent samples come from the same distribution. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2008, 4, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Company | Number of Disabled Respondents by Each Company (Total = 141) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 7 |

| 2 | 8 |

| 3 | 13 |

| 4 | 11 |

| 5 | 2 |

| 6 | 7 |

| 7 | 1 |

| 8 | 10 |

| 9 | 4 |

| 10 | 18 |

| 11 | 9 |

| 12 | 3 |

| 13 | 4 |

| 14 | 9 |

| 15 | 2 |

| 16 | 7 |

| 17 | 4 |

| 18 | 1 |

| 19 | 5 |

| 20 | 3 |

| 21 | 4 |

| 22 | 2 |

| 23 | 3 |

| 24 | 3 |

| 25 | 1 |

| Gender | Number of Individuals (of 141 Respondents) |

|---|---|

| Males | 80 |

| Females | 61 |

| Age | Number of Individuals (of 141 Respondents) |

|---|---|

| 18–25 y.o. | 10 |

| 26–30 y.o. | 24 |

| 31–35 y.o. | 31 |

| 36–40 y.o. | 25 |

| 41–45 y.o. | 15 |

| 46–50 y.o. | 35 |

| Older than 50 | 1 |

| Working Experience (Years in Service) | Number of Individuals (of 141 Respondents) |

|---|---|

| Less than 5 YEX | 17 |

| 6–10 YEX | 29 |

| 11–15 YEX | 28 |

| 16–20 YEX | 22 |

| 21–25 YEX | 17 |

| 26–30 YEX | 27 |

| More than 30 YEX | 1 |

| Number of Question | The Content of the Question | Type of Answer | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1 | What is the average period of employment of a disabled person in your enterprise over the previous 12 months? | Answer indicated as a number expressed in complete months | These questions are intended to verify and compare the differences in employment periods of disabled and able-bodied. |

| Question 2 | What is the average period of employment of the so-called able-bodied person in your company from the previous 12 months? | Answer indicated as a number expressed in complete months | |

| Question 3 | What does your company bear the average costs of employing a disabled person? | Multiple-choice answer: the cost of adapting the workplace; the cost of training the employee; other costs (what sort of?): ______ | This question is intended to allow to verify the structure of costs of employment that the company should spend to effectively address the needs of disabled persons. |

| Question 4a | What is the average amount of each of the above-mentioned costs? - cost of adapting the workplace (PLN): | Single-choice answer: (a) less than 2500; (b) 2500–4999; (c) 5000–7499; (d) 7500–9999; (e) 10,000–12,500; (f) 12,500–15,000; (g) higher (how high?): _____________ | These questions are intended to allow to verify the amount of costs of employment that the company should bear (separately on adapting the workplace and training) to effectively address the needs of disabled persons. |

| Question 4b | What is the average amount of each of the above-mentioned costs?—cost of training an employee on the job (PLN): | Single-choice answer:(a) less than 1000;(b) 1000–1999;(c) 2000–2999;(d) 3000–3999;(e) 4000–4999;(f) higher (how high?): _____________ | |

| Question 5 | If in question 3 you indicated other costs, please also provide the highest ones below other costs (please round the amount to PLN 1000): | Multiple-choice answer: -other cost 1 (please name the cost): ________________ in the amount of: ________ (please give amount of above-mentioned cost in PLN): -other cost 2 (please name the cost): ________________ in the amount of: ________ (please give amount of above-mentioned cost in PLN): -other cost 3 (please name the cost): ________________ in the amount of: ________ (please give amount of above-mentioned cost in PLN): -other cost 4 (please name the cost): ________________ in the amount of: ________ (please give amount of above-mentioned cost in PLN): -other cost 5 (please name the cost): ________________ in the amount of: ________ (please give amount of above-mentioned cost in PLN): | This question is intended to provide more detailed information about the structure of expenditures that companies bear to effectively hire the disabled persons. |

| Question 6 | In your opinion, can any of the above-mentioned costs of employing a disabled person be reduced when recruiting another disabled person for the same position in the future? (This may occur case, for example, when the adaptation of the workplace or the training materials are suitable for use by other disabled employees in the future) | Single-choice answer: (a) yes; (b) no; (c) it is difficult to say; | This question is intended to provide the information about the possibility of optimization of company expenditures on hiring disabled. |

| Question 7 | If you answered yes to the above question, which of the above-mentioned costs can be indicated as such costs? | Free written expression | This question is intended to provide more detailed information about the way to optimize the company expenditures on hiring disabled. |

| Question 8 | If you answered no to question 6, or you chose the answer c), pleaseindicate why? | Free written expression | This question is intended to provide more detailed information to understand why the company costs of hiring disabled persons are hard or impossible to be optimized. |

| Question 9 | How, in your opinion, is the productivity of a disabled person (after incurring the above costs) compared to able-bodied workers? (−90 means about 90% less work efficiency, +90 means about 90% more work efficiency) | A number between −90 to +90. | This question is intended to provide the information about the effectiveness of above-listed company expenditures on hiring disabled persons on their work productivity. |

| Question 10 | Please specify, what is the area of functioning of your company | Single-choice answer: (a) production (b) services (c) both of above (d) other (which?) ______ | It is expected that the answers may vary depending on the area (industry). This question is intended to verify the areas with higher opportunities to hire disabled effectively (where they can really compare with able-bodied persons) and where the cost of their employment can be more easily optimized. |

| Question 11 | How long is the company present on the market? | Answer indicated as a number expressed in complete years | It is expected that the answers may vary depending on the time the company is present on the market. This question is intended to verify the differentiation taking under consideration the factor of time of presence on the market. |

| Question 12 | How many employees your company employs? | Answer indicated as a number | It is expected that the answers may vary depending on the size of the company. This question is intended to verify the differentiation taking under consideration this factor. |

| Number of Question | The Content of the Question | Type of Answer | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1 | Which of the following factors are the most important in your case when choosing a job? | Single-choice answer: (a) preparation of the workplace strictly taking into account my disability; (b) the possibility of flexible selection of remote work; (c) the ability to perform 100% of entrusted tasks from home; (d) availability of a dedicated person to help people with disabilities in the company; (e) other factor (what?): .................. | This question is intended to distinguish the most important factors (when choosing the job) for disabled persons. |

| Question 2 | How long have you been employed by one employer for the longest time? | Answer indicated as a number expressed in complete months | The answers for these questions may let to compare the average time of employment declared by the disabled people and declared by employers (presented in the previous Table) |

| Question 3 | Please describe what, in your opinion, has a key impact on the situation in a given place (company), where you work well and you do not want to change job position: | Free written expression | This question is intended to distinguish the most important aspects (for disabled persons) required to long term satisfaction about their job |

| Question 4 | What is the total period of professional activity? | Answer indicated as a total number of months of taking a professional job | This question is intended to realize the value of the answers given in questions 1–3. for example, such value would be limited, if a disabled person is professionally active for a very short period. |

| Question 5 | Do you know the indicative costs that your employer has incurred to make it possible to offer a job to you? | Single-choice answer: (a) yes, it was the amount of approximately (please round to the nearest thousand PLN): _____ . (b) I don’t know. | This question is intended to analyze and verify if disabled persons are aware of the scope of expenditures made of their workplace. |

| Question 6 | Do you think that the employer’s incurrence of these costs in any way makes in the future, will it be easier for you to find another job? | Single-choice answer with one filled-in sentence: (a) yes, because: _________ (b) no. | This question is intended to analyze and verify the long-term impact of expenditures on the workplace for disabled people. |

| Question 7 | How do you rate your own performance at your job compared to the so-called able-bodied workers? (−90 means about 90% less work efficiency, +90 means about 90% more work efficiency) | A number between −90 to +90. | This question is intended to get to know and analyze the self-opinion of disabled persons about the performance of their own work. |

| Question 8 | What is your gender? | Single-choice answer: (a) female (b) male | It is expected that the answers may vary depending on the sex of the respondent. This question is intended to distinguish it. |

| Question 9 | What is your age? | Answer indicated as a number expressed in complete years | It is expected that the answers may vary depending on the age of the respondent. This question is intended to distinguish it. |

| Question 10 | What is your occupation? | Answer expressed as one filled-in sentence: ____________ | It is expected that the answers may vary depending on the occupation of the respondent. This question is intended to distinguish it. |

| Question 11 | Could you be so kind and point out what is your disability? | Answer expressed as one filled-in sentence: ____________ | It is expected that the answers may vary depending on the sort of disability of the respondent. This question is intended to distinguish it. |

| Question 12 | Where do you live? | Single-choice answer: (a) Countryside (b) City up to 50,000 residents (c) City 51–100 thousand residents (d) City 101–500 thousand residents (e) City over 500,000 residents | It is expected that the answers may vary depending on the place of living of the respondent. This question is intended to distinguish it. |

| Individual Preparation of the Workplace in Terms of the Disability of a Specific Person | Possibility of Flexible Selection of Remote Work | Possibility to Perform 100% of Entrusted Tasks from Home | Availability in the Company of a Dedicated Person to Help People with Disabilities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor disability | 27 | 7 | 9 | 9 |

| Intellectual disability | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 |

| Visual impairment | 8 | 5 | 17 | 5 |

| Hearing/speech disability | 5 | 6 | 14 | 7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chajduga, T.; Ingaldi, M. Hiring Disable People to Avoid Staff Turnover and Enhance Sustainability of Production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910577

Chajduga T, Ingaldi M. Hiring Disable People to Avoid Staff Turnover and Enhance Sustainability of Production. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910577

Chicago/Turabian StyleChajduga, Tomasz, and Manuela Ingaldi. 2021. "Hiring Disable People to Avoid Staff Turnover and Enhance Sustainability of Production" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910577

APA StyleChajduga, T., & Ingaldi, M. (2021). Hiring Disable People to Avoid Staff Turnover and Enhance Sustainability of Production. Sustainability, 13(19), 10577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910577