A Guest at Home: The Experience of Chinese Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

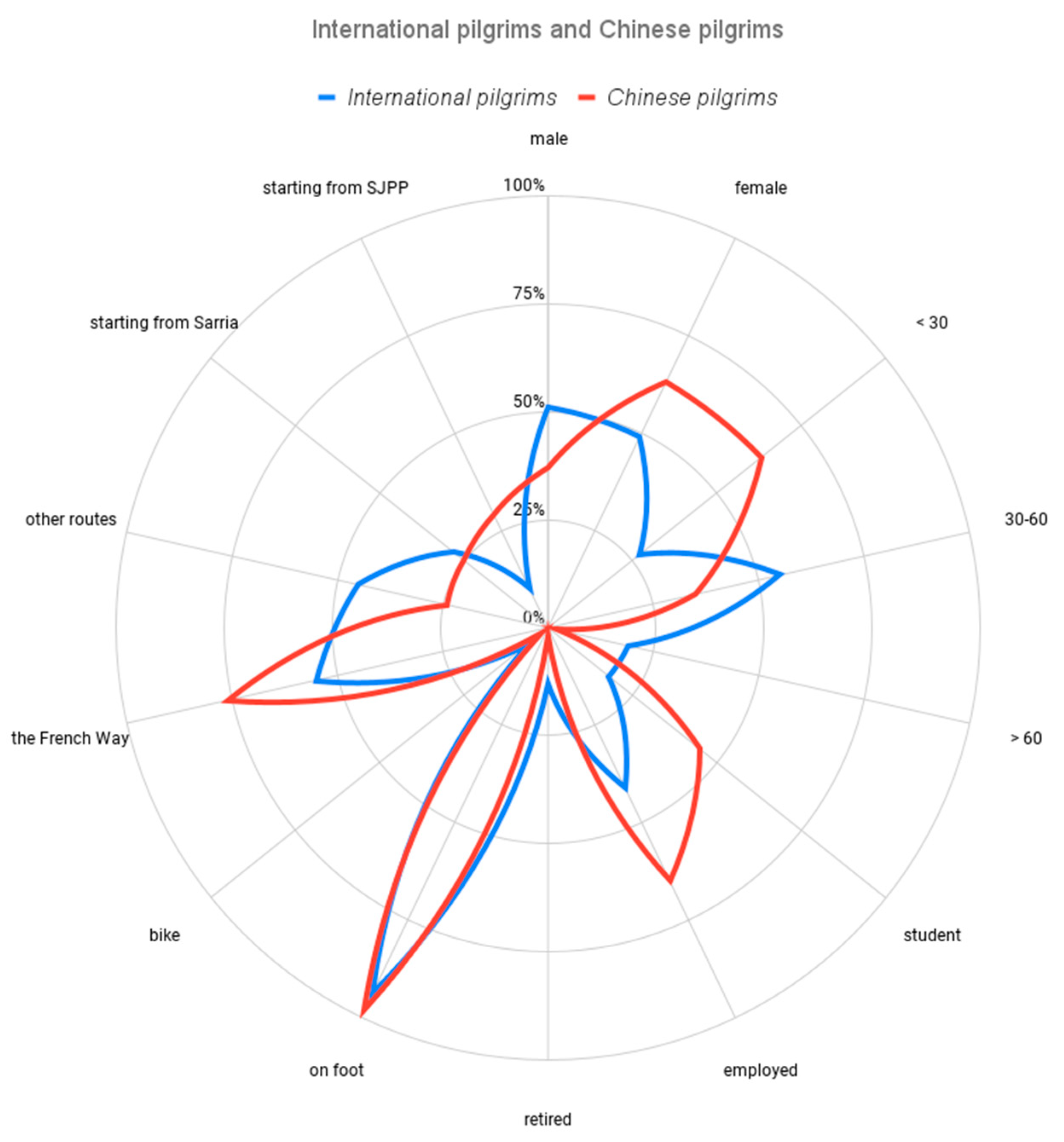

3.1. Pilgrim Profile

3.2. Movitations

‘I chose to walk the Camino not only because I watched the movie The Way. Most importantly it’s because I wanted to stop, to ask questions about myself, to clarify doubts for myself. (JR35)‘I don’t seem to have a clear goal for walking the Camino, I simply wanted to become stronger and more courageous.’ (JR90)‘I was attracted by the natural landscape, the cultural landscape such as architecture, local life along the Camino presented in the movie The Way. It’s like a landscape movie, but it has much spiritual elements, reflections, etc., (which leads me to make) reflections on my own present life.’ (IN9)

3.3. Experience of Spain

‘When the locals give us a thumbs up, we feel incredible strength! Everyone greets us kindly and respects the pilgrims with backpacks and shells.’ (IN6)‘Walking in Spain is a very comfortable experience. Besides the picturesque landscape, the relaxing and calm life attitude of the local people shows a confident universal value that can exist only after one is self-sufficient.’ (JR6)‘Maybe it’s under the influence of Christian views or Western customs on life and death, their cemeteries are located inside their village, their relatives can go and visit them anytime, they don’t take death as a taboo like us.’ (JR64)

3.4. The Camino as a Unique Culture

‘In the mountains I encountered several times ‘fruit self-service’, not machines, ‘self-service’ here means not supervised. Owners put out for sale their grapes, bananas, apples, oranges, packed nuts, etc, each for 1 euro, and they left a locked cash box next to it. I’ve never seen this in cities, I think I’ll never see it. Only here on the Camino you can see something like this.’ (JR103)The volunteers at the Gaucelmo Albergue reminded me of other warm-hearted volunteers along the way, such as Grandpa Francisco, Antie Rosa, Uncle Jose Luis, etc.. The volunteers are indeed a beautiful sight of the Camino. In fact I want to thank them for their warmth and welcome to all pilgrims regardless of their cultures and backgrounds, which have allowed the Camino to become a unique, charming route of cultural diversity.’ (JR73)‘The Camino stands for a lifestyle in its original and simple form: walking, carrying your own bags, living in hostels with limited conditions.’ (IN2)

‘A Western grandpa brought his little grandson to experience the Camino. It seems Westerners start to cultivate independence in their children at an earlier age than Easterners.’ (JR63)‘It was raining in the morning when I left…Auntie Irene from Scotland illuminated my path like an angel and reminded me from time to time about mud and puddles. I encountered all the time angels like her on the way, it has nothing to do with nationality or age.’ (JR28)‘I’m very lucky that I encountered a community that’s like a family: we use ‘Camino family’ to address each other and name our team as ‘Camino legend’. We have ten young people from eight countries and five continents: we are Chinese, German, Irish, Canadian, American, French, Australian and Brazilian.’ (JR54)

3.5. Evaluation of the Pilgrimage Route

‘Many things happened before the Camino, I was preoccupied and felt split into two: one being the body and the other the mind. On the Camino the two ‘I’s became one again…I recalled what I originally intended to pursue.’ (IN10)‘After those days on the way I now understand why the Camino is called a journey that touches the mind, and I come to believe that everyone can find here the meanings for the self.’ (JR65)‘The Camino is truly a platform for cross-cultural communication… This route is a get-together for the world, open your heart and you can dialogue with the world. Isn’t that exciting!’ (JR22)

‘There are no such hiking trails in China, with supplies in every 20 km along the entire trail. The facilities are perfect. That’s rare.’ (IN8)‘It is not very commercialized and has maintained the original ecology. The preservation of natural environment and culture is very good.’ (IN3)‘I had little preparation in understanding the churches. We visited some of them but didn’t really understand them. If there are any stories or background history, we must have missed that.’ (IN2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Journey of Authenticity and Harmony

4.2. Evolving Modes and Plural Centers of Travel Experience

4.3. Similarities and Differences between Chinese and Western Pilgrims

4.4. Key Attractions of the Camino for Chinese Pilgrims

4.5. Reflection on Sustainable Management of Cultural Route Heritage

- (1)

- First and foremost, authenticity should be positioned as the most fundamental and central attribute of heritage in order to keep the Camino attractive and cherished.

- (2)

- Multilingual information on the history, culture, and art of heritage sites along the Camino would also help Chinese pilgrims to intellectually appreciate their Camino more, e.g., by providing relevant digital information accessible through an on-site QR code, or adding images of the food on restaurant menus to improve the gastronomic experience.

- (3)

- An inclusive approach that welcomes multicultural diversity and universal fraternity would continue to inspire and foster cross-cultural dialogue, mutual understanding, and collaboration in the face of the common challenges of the contemporary world, such as the pandemic and climate change.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The Camino tends to be attractive to young, middle-class professionals from large cities in China and also to Chinese students living in Europe. The promotion targeted at these groups might be more effective in motivating them to experience the cultural route heritage. However, this does not rule out the possible appeal of the Camino to more general Chinese tourists who have become more diversified and experience-seeking [70], particularly among lovers of outdoor activities, religious tourists, and, perhaps, among the well-off retired population [71].

- (2)

- Adoption of the online platforms that are most familiar to the prospective groups, such as the most popular travel websites and social media accounts used by young, middle-class professionals, or the school newsletters or cultural activity programs in European universities where Chinese students study or utilizing the networks of university professors who teach Chinese students, particularly in Spain.

- (3)

- In addition to highlighting the natural landscape and cultural heritage, the authentic quality of the gastronomy, multicultural encounters, and the spiritual profoundness that makes the Camino experience so unique could also be featured in the promotional efforts aimed at Chinese tourists.

- (4)

- The presentation of the Camino could be delivered through various media, including online journals and articles, books, movies, video clips, promotional conferences, exhibitions, etc., and the attention could be focused on the personal stories of pilgrims through these presentations, as this is more likely to ‘wake up’ the otherwise latent desires of other tourists for personal growth and intercultural experiences.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, M. The Cultural Heritage of Pilgrim Itineraries: The Camino de Santiago. Journeys 2014, 15, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lois-González, R.; Santos, X.M. Tourists and pilgrims on their way to Santiago. Motives, Caminos and final destinations. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2015, 13, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim’s Office. Available online: https://oficinadelperegrino.com/en/statistics/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Nash, D.; Smith, V.L. Anthropology and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N. The tourist experience: Conceptual developments. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Ryu, K.; Hussain, K. Influence of Experiences on Memories, Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions: A Study of Creative Tourism. J. Trav. Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. The shaping of tourist experience: The importance of stories and themes. In The Tourism and Leisure Experience: Consumer and Management Perspectives; Morgan, M., Lugosi, P., Ritchie, J.R.B., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2010; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. A phenomenology of tourist experience. Sociology 1979, 13, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliade, M. The Myth of Eternal Return; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1971; pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V. The center out there: The pilgrim’s goal. Hist. Relig. 1973, 12, 191–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Stage authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociolo. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.L. Introduction: The quest in guest. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, T. Asian tourism and the retreat of anglo-western centrism in tourism theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Cohen, S.A. Current Sociological Theories and Issues in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 2177–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jensen, Ø.; Lindberg, F.; Østergaard, P. How Can Consumer Research Contribute to increased Understanding of Tourist Experiences? A Conceptual Review. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luik, E. Meaningful pain: Suffering and the narrative construction of pilgrimage experience on the Camino de Santiago. Suomen Antropol. J. Finn. Anthropol. Soc. 2012, 37, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, L. How Long Does the Pilgrimage Tourism Experience to Santiago de Compostela Last? Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2013, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, M.; Tesfahuney, M. Performing the “post-secular” in Santiago de Compostela. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Antunes, A.; Henriques, C. A closer look to Santiago de Compostela’s pilgrims through the lens of motivations. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojo, L. Chinese tourism in Spain: An analysis of the tourism product, attractions and itineraries offered by Chinese travel agencies. Cuad. Tur. 2016, 37, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medina-Muñoz, D.R.; Medina-Muñoz, R.D.; Zúñiga-Collazos, A. Tourism and Innovation in China and Spain: A Review of Innovation Research on Tourism. Tour. Econ. 2013, 19, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights, 2019 ed.; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights, 2020 ed.; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, V. The Chinese Outbound Travel Market. European Commission. Available online: https://ecty2018.org/ready-for-china/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Majdoub, W. Analyzing cultural routes from a multidimensional perspective. Almatourism J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2020, 1, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Overall, J. The Wrong Way: An alternative critique of the Camino de Santiago. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 22, 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. The Santiago de Compostela Declaration. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806f57d6 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- UNESCO. Routes of Santiago de Compostela: Camino Francés and Routes of Northern Spain. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/669/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Lois-González, C.R.; Santos-Solla, X.M.; Taboada-de-Zuniga, P. New Trends in Urban and Cultural Tourism: The Model of Santiago de Compostela; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2011; pp. 209–237. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, L.; Santos, X.M. Analysis of Territorial Development and Management Practices along the Way of St James in Galicia. In Managing Religious Tourism; Griffiths, M., Wiltshier, P., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Li, W.; Liu, J. A study on status, features and development strategies of Chinese cultural routes. Chin. Land. Arch. 2016, 9, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Song, Y. Cultural Routes in China; China publishing Group: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, C.; Pimenta, E.; Gonçalves, F.; Rachao, S. A new research approach for religious tourism: The case study of the Portuguese route to Santiago. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2012, 4, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, L.; De Courcier, S.; Farias, M. Rise of Pilgrims on the Camino to Santiago: Sign of Change or Religious Revival? Rev. Relig. Res. 2014, 56, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farias, M.; Coleman III, T.J.; Bartlett, J.E.; Oviedo, L.; Soare, P.; Santos, T.; Bas, M.C. Atheists on the Santiago Way: Examining Motivations to Go On Pilgrimage. Sociol. Relig. A Quar. Rev. 2019, 80, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.S.; King, B. The sacred and the profane: Identifying pilgrim traveler value orientations using means-end theory. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, N.L. Pilgrim Stories: On and Off the Road to Santiago; University of California, Press Berkeley: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, K. Fumbling: A Pilgrimage Tale of Love, Grief, and Spiritual Renewal on the Camino de Santiago; Doubleday: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Genoni, P. The pilgrim’s progress across time: Medievalism and modernist on the road to Santiago. Stud. Travel Writ. 2011, 15, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husemann, K.C.; Eckhardt, G.M. Consumer deceleration. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 45, 1142–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Corinto, G.; Malek, A. New Trends of Pilgrimage: Religion and Tourism, Authenticity and Innovation, Development and Intercultural Dialogue: Notes from the Diary of a Pilgrim of Santiago. AIMS Geosci. 2016, 2, 152–165. [Google Scholar]

- Slavin, S. Walking as spiritual practice: The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Body Soc. 2003, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, A. The unexpected real: Negotiating fantasy and reality on the road to Santiago. Liter Aesthet. 2009, 19, 50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V.W. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure; Aldine Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V.W.; Turner, E. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cazaux, F. To be a pilgrim: A contested identify on Saint James’ Way. Tourism 2011, 59, 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Business Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, D. The blogosphere as a market research tool for tourism destinations: A case study of Australia’s Northern Territory. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffe, D.; Lacy, S.; Fico, F.G. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using the matica nalysis in psychology. Qual.Res.Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua Online Chinese Dictionary. Available online: http://xh.5156edu.com/html5/70211.html (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 27, 835–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. ‘Authenticity’ in tourism studies: Aprés la lutte. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2007, 32, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C. Tourism and the spiritual philosophies of the ‘Orient’. In Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys; Timothy, D.J., Olsen, D.H., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, J. Discussion on Confucian Self–Cultivation and Buddhist Practice. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. 2020, 29, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Scott, N.; Tao, L.; Ding, P. Chinese tourists’ motivation and their relationship to cultural values. Anatolia 2018, 30, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Stringer, L.A. The Impact of Taoism on Chinese Leisure. World Leis. J. 2000, 42, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, X. The position and modern value of Taoism in Chinese traditional cultural. J. Hunan Univ. 2006, 20, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, H. Analysing the Cultural Meaning of ‘yuan’ and ‘yuanfen’. Nankai Linguist. 2004, 1, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Zuo, B. Contextual Incidents, Interpersonal Orientation and Interpersonal Satisfaction. Psychol. Explor. 2008, 28, 88–92, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P.L.; Wu, M.; Osmond, A. Puzzles in Understanding Chinese Tourist Behavior: Towards a Triple-C Gaze. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2013, 38, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, T.; Pali, S. Pilgrimage today: The meaning- making potential of ritual. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2013, 16, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, T.; Nilsson, M.; Santos, X. The way to Santiago beyond Santiago. Fisterra and the pilgrimage’s post-secular meaning. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 12, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Barlar, S.H. Modern Influences along an Ancient Way: Pilgrimage and Globalization. In Pilgrimage as Transformative Process; Warfield, H.A., Hetherington, K., Eds.; Brill: Leidon, The Netherlands; Rodopi: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, E. Tourist Destination Management: Issues, Analysis and Policies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tilson, D.J. Religious-spiritual tourism and promotional campaigning: A church-state partnership for St. James and Spain. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2005, 12, 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Riera, I. Proyección de las Rutas Compostelanas en China. Available online: https://www.mundiario.com/articulo/claves-de-china/proyeccion-rutas-compostelanas-china/20210324204410215309.html (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- UNWTO. Guidelines for the Success in the Chinese Outbound Tourism Market; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Jin, X.; Weaver, D. Profiling the elite middle-age Chinese outbound travelers: A 3rd wave? Cur. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Percentage | International Pilgrims (2019) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gender | Male | 46 | 37% | 51% |

| Female | 78 | 63% | 49% | |

| age | <30 | 78 | 63% | 55% |

| 30–60 | 44 | 35% | 27% | |

| >60 | 2 | 2% | 19% | |

| occupation | student | 55 | 45% | 18% |

| employed | 51 | 41% | 65% | |

| retired | 3 | 2% | 13% | |

| not indicated/other occupation | 15 | 12% | 4% | |

| religion | non | 114 | 92% | Not available |

| Christian | 4 | 3% | Not available | |

| not indicated | 6 | 5% | Not available | |

| route | French Way | 94 | 76% | 55% |

| other routes | 30 | 24% | 45% | |

| starting point | Saint Jean Pied de Port | 36 | 29% | 10% |

| Sarria | 31 | 25% | 28% | |

| mode | on foot | 121 | 98% | 94% |

| bike | 3 | 2% | 6% | |

| organization | alone | 66 | 53% | Not available |

| with companions | 58 | 47% | Not available |

| Key Words of Benefit | Numbers of Pilgrims Who Used the Key Word | Percentage among All Pilgrims | Key Words of Attribute | Number of Pilgrims Who Used the Key Word | Percentage among All Pilgrims |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| growth | 17 | 14% | life metaphor | 29 | 23% |

| happiness | 14 | 11% | magical | 28 | 23% |

| feeling touched | 10 | 8% | journey of the mind | 27 | 22% |

| goodness | 9 | 7% | personal | 18 | 15% |

| inner peace | 9 | 7% | worthwhile | 14 | 11% |

| purity | 9 | 7% | intercultural | 14 | 11% |

| warmth | 9 | 7% | unforgettable | 12 | 10% |

| gratefulness | 7 | 6% | historical-cultural | 7 | 6% |

| liberated | 6 | 5% | universal | 3 | 2% |

| life answer | 6 | 5% | |||

| new life | 4 | 3% | |||

| rebalance | 3 | 2% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, K.; Labajo, V.; Ramos, I.; González del Valle-Brena, A. A Guest at Home: The Experience of Chinese Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910658

Zhang K, Labajo V, Ramos I, González del Valle-Brena A. A Guest at Home: The Experience of Chinese Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910658

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ke, Victoria Labajo, Ignacio Ramos, and Almudena González del Valle-Brena. 2021. "A Guest at Home: The Experience of Chinese Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910658

APA StyleZhang, K., Labajo, V., Ramos, I., & González del Valle-Brena, A. (2021). A Guest at Home: The Experience of Chinese Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. Sustainability, 13(19), 10658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910658