The Collaborative Process of Sustainable Innovations under the Lens of Actor–Network Theory

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Characteristics of Sustainable Innovations

2.2. The Collaborative Process of Sustainable Innovation

2.3. The Sociotechnical Analysis of ANT

2.4. The Translation Approach of ANT

3. Method and Data

3.1. Case Study and Selection

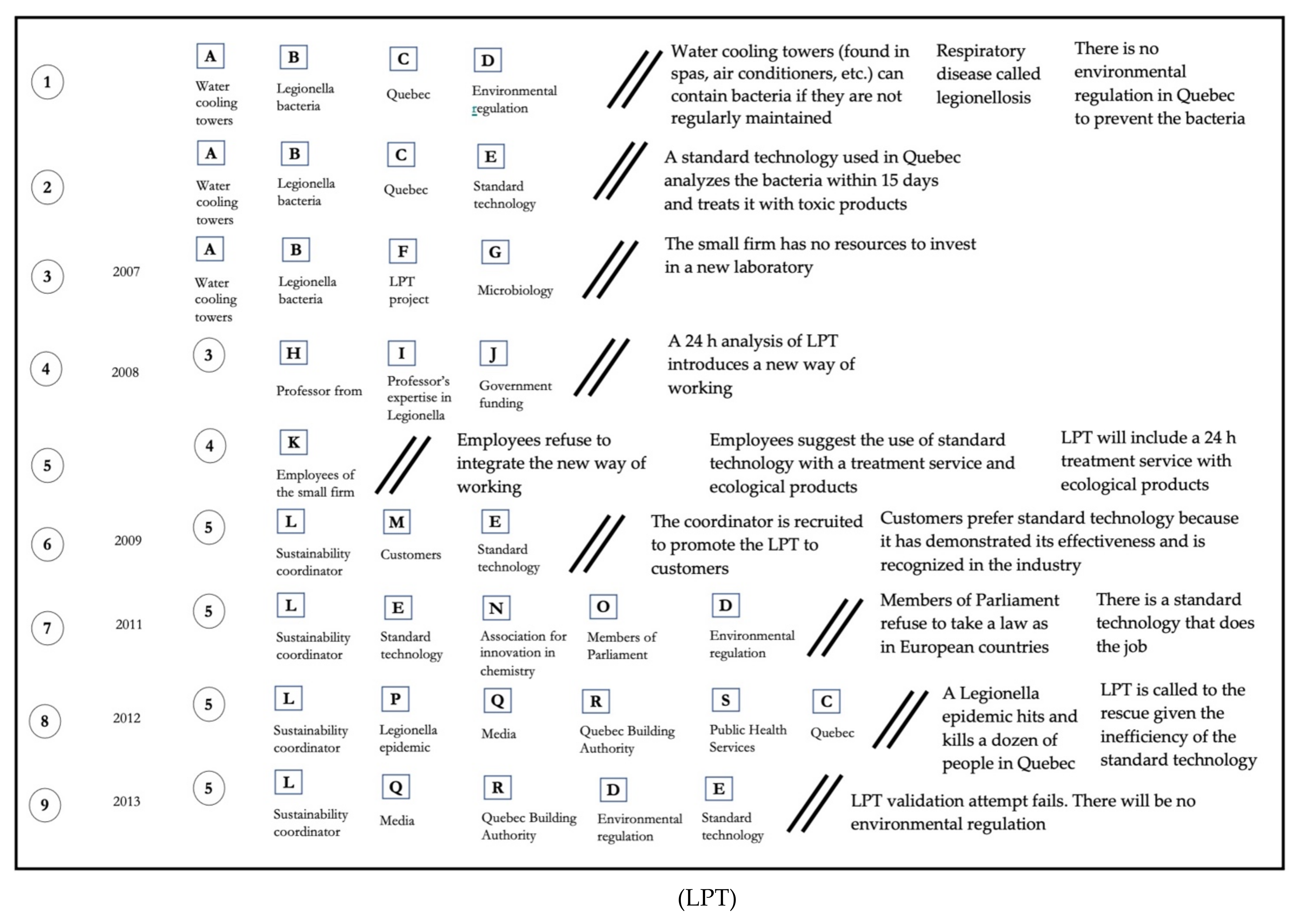

3.1.1. The Case of the Legionella Preventive Treatment (LPT)

“The development of our technology has been a challenge above all because no company uses it, although in the world of scientific research its basic foundations are known.”

“I have met about 300 companies, over 1000 managers. The problem is the analytical technique used in our green chemistry was very controversial for those of the managers who were chemists, scientists, or researchers. The preference was for the more traditional analytical technique. Under these conditions, my message was no longer focused on our technology, but on the passing of a law or a new regulation.”

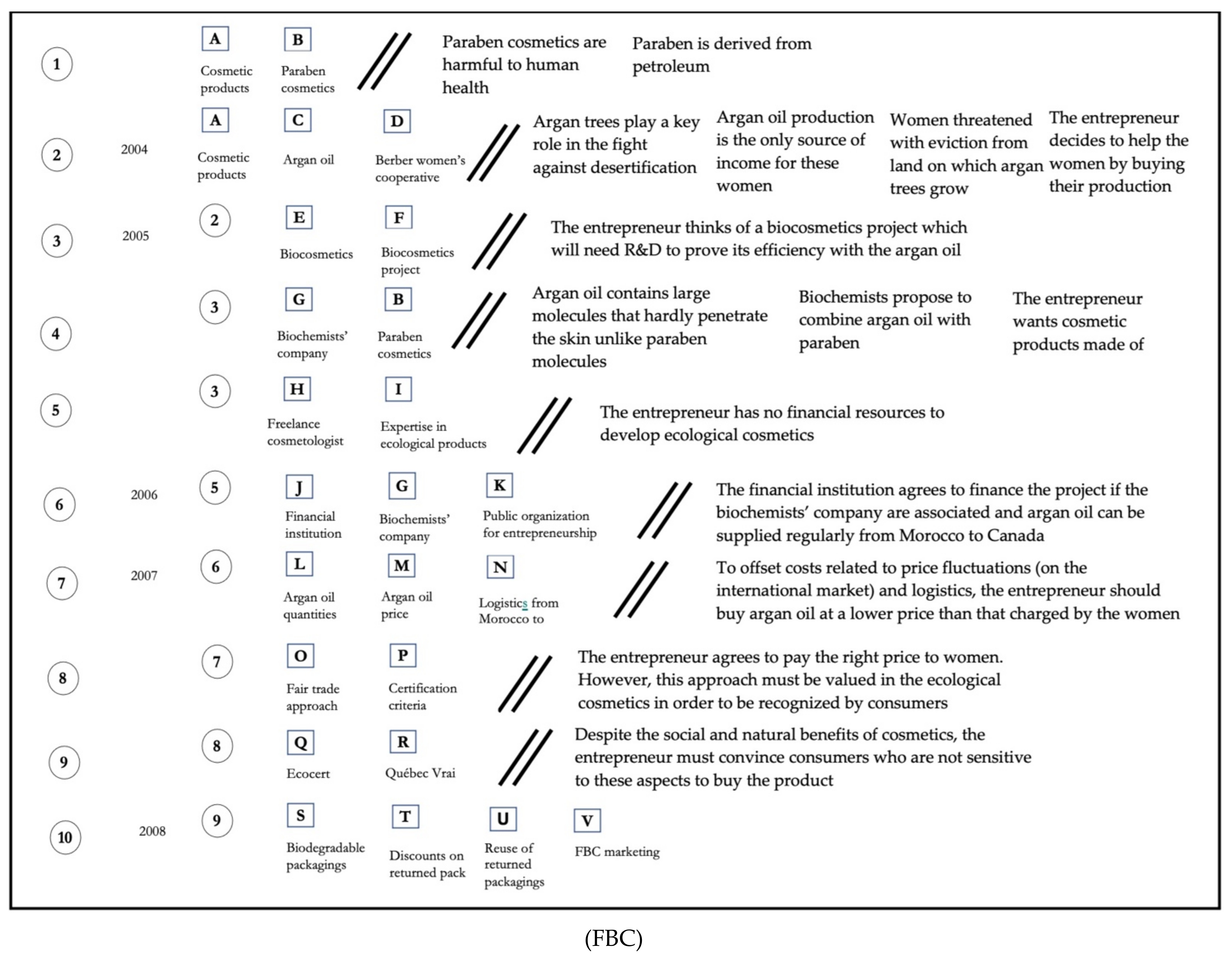

3.1.2. The Case of the Fair Biocosmetic (FBC)

“Developing a cosmetic product from plants and especially argan oil was not really done when technology allowed it, at least we believed in it. So, we did a lot of compromises as well as research and development (20% of turnover) for almost two years to arrive at an ecological and fair product certified by Ecocert (Ecocert is an independent organization responsible for monitoring, on the ground, the respect of environmental and social requirements through its own standards (e.g., ecological and biological cosmetics). Through its contribution to the development of organic farming, this company has become a benchmark for organic certification worldwide.) and Québec Vrai (Québec Vrai is an organization accredited in Quebec to certify products according to ISO standards as well as to verify the supply chain of certified products.).”

- The innovation must follow the definition of SI: as indicated in the introduction of this paper, SIs are innovations (such as technology, products/services, organizational or commercial methods, institutional change) that significantly reduce their negative (or improve their positive) economic, environmental, and/or social effects.

- The SI must be developed within SMEs: the manager’s commitment to sustainability issues, the organizational flexibility of SMEs, the closed relationships (proximity) with stakeholders, and the importance of external collaborations, are unique to the context of SMEs, and are conditions needed to develop SIs [31,109,110].

- The SI process must be representative of a failure and a success. Whereas the “tendency” is often to neglect the failure and to emphasize the success, behind the failure, there are more lessons to learn from than the success [111,112]. It is the moment when, for a future situation, someone can give advice or insight to another individual [111].

- The story of each SI development must allow observing interactions between actors and difficulties emerging from this process: the authors of [111] warn against believing for a moment those edifying stories of innovations that retrospectively invoke the absence of competing demands that generate difficulties during the collaborative process.

3.2. Data Collection and Organizing

3.3. The Sociotechnical Graph Method

4. Results

4.1. The Characteristics of the SIs

“In Canada and Quebec, there is no company that has such technology, and it takes expertise to be able to apply it. Rather, companies in the industry have been using another well-known technology for many years. However, it has shown its limits in the fight against the bacteria and does not consider environmental aspects (e.g., excess concentrations of chlorine and ineffective chemical treatments harmful to the environment) and social (e.g., risk of contamination to humans due to the very long detection time of the bacteria, i.e., two weeks, toxicity of the treatment products which may have negative effects on health).”

“There are two types of cosmetics, i.e., synthetic cosmetics using excipients derived from the oil industry, and biocosmetics which use vegetable excipients and certified organic. For a cosmetic to carry the organic label, it must meet the reference codes of the various organic certification bodies. Therefore 95% of its ingredients must be certified organic. Herbal excipients are as effective as chemical excipients. They also provide vitamins, minerals, proteins, and unsaturated fatty acids to the skin. Another advantage is the absence of side effects caused by parabens derived from petroleum which are used as preservatives and emulsifiers in the cosmetics industry. Indeed, these are found more and more in cancerous tissues. Therefore, in Europe, cosmetics companies have almost all removed them from their products, but here in Quebec, 75% contain them.”

4.2. The Collaborative Process of SIs

- Version (1): there are two actors (A and B) at the beginning of the process. Actor A holds the rank 1 and B, the rank 2 in the alphabetical order (E1 = 2) meaning that the FBC have interested two different actors. The sustainable issues of the classic cosmetics (derived from parabens and harmful to humans) lead to the development of the FBC (version 2).

- Version (2): two new actors (C and D, N2 = 2). Actor A remains in the process and then becomes an ally (A2 = 1), C holds the rank 3, and D, the rank 4 in the alphabetical order (E2 = 4), meaning that the FBC has interested four different actors. The aggregation of new actors mobilized in the process is ANA2 = 2 (i.e., C and D), but B leaves the process (it is a loss, LNA2 = 1). The socioeconomic issue of the cooperative’s women prompts the manager to pursue the development of the FBC (version 3).

- Version (3): two new actors (E and F, N3 = 2). All actors at version 2 (i.e., A, C, and D) remain in the process and there are now three allies (A3 = 3). E holds the rank 5 and F, the rank 6 in the alphabetical order (E3 = 6). The aggregation of new actors is now ANA3 = 2 (i.e., E and F), no loss of actors (LNA3 = 0). The development of a biocosmetic made with 100% argan oil needs R&D capacities, which the manager does not have (version 4).

- Version (4): two new actors (G and B come back in the process, N3 = 2). All actors at version 3 (i.e., A, C, D, E, and F) remain and there are now five allies (A4 = 5). G holds the rank 7 in the alphabetical order (E4 = 7), the aggregation of new actors is ANA4 = 2 (i.e., G and B), and no loss of actors (LNA4 = 0). The biochemist company proposes to combine argan oil with paraben (version 5).

- Version (5): two new actors (H and I, N5 = 2). All actors at version 3 remain (A5 = 5), H holds the rank 8 and I, the rank 9 in the alphabetical order (indicator E5 = 9). The aggregation of new allies is ANA5 = 2 (i.e., H and I), but G and B leave the process at version 4 (LNA5 = 2). The manager does not have resources to invest in ecological biocosmetics (version 6).

- Etc.

“The company embarked on the development of the innovation which will involve internal players, namely the company’s laboratory technicians. The latter foresee a change in their tasks which will henceforth be devoted to the development of the technology. For some technicians, especially the oldest in the company, given that it is a question of solving a problem that does not yet exist in Quebec, it is not necessary to invest in the development of a new analysis technology if there is already a technology that has a broad consensus in the industry. We must be content with conventional technology while focusing on the use of ecological products instead of toxic products. For technicians, the company can stand out above all in terms of treatment with ecological products. Based on this new idea coming from the laboratory technicians, we decide to develop a prototype that combines the new analysis technology and treatment with ecological products.”(Vice-president of SI)

“Thanks to biochemists and the cosmetologist, I understand that I can use the argan oil to develop a cosmetic product thus ensuring regular income for the women’s cooperative. I did not know anything about the cosmetics industry. The more I learned about this world, the more I realized that many of the ingredients in cosmetics are derived from petroleum, and people put them on their faces! Under these conditions, I understand that there is another opportunity that presents to me: showing Quebec women the virtues of argan oil for their skin.”

“Owners of cooling towers were telling me that it’s not even mandatory to do preventative testing, although they know their cooling towers are contaminated. In fact, they don’t want to do it for economic reasons. And it reminded me of the movie called ‘Erin Brockovich Alone Against All’. In this movie, people in a small town in California contracted serious illnesses (such as cancer) caused by drinking water containing toxic discharges from the cooling water of a factory. In short, owners of cooling towers resistance have led us to focus on the legislative aspect.”(Sustainability manager)

“For representatives of Public Health Services, although they are convinced of the relevance of our technology, but it is not the standard in North America and Canada, although it allows screening in 24 h with products that are not harmful to humans and the environment, while with usual technologies, it takes 15 days with toxic chemical treatments.”(V.P. of an SI)

“Thus, faced with 15 members of parliament we present ourselves as ‘the representatives of the bacteria’. We ask MPs to wear a pin bearing the sign of the bacteria. Our arguments were first supported by the crises that took place in France, the United Kingdom, Australia, and above all, by the existence of legislation in France, a country from which the laws of Quebec are generally based.”(Sustainability manager)

“For some members of parliament, ‘there is already a regulation’; which is not in fact the case. For others, ‘we must not frighten the population since there is no epidemic, and anyway there is already the classical technology to fight the bacteria if it occurs’. The company claims that this technology has shown its limits even in France in terms of response time and the negative environmental impact of treatments. In addition, a law can be adopted for prevention. Among these members of parliament, only one, himself a scientist, supports the ‘representatives of the bacteria’. He then offers to discuss the case with his colleagues. Finally, the meeting gives birth to a mouse.”(V.P. of Communication)

“In 2012, a Legionella epidemic broke out in Quebec, and the media echoed the families of a dozen dead and more than a hundred infected people. The company is then called to the rescue first by the media and then by the authorities in place, the ‘Régie des Bâtiment du Québec (RBQ)’, the Public Health Services and the city where the contaminated tower was located.”(VP of an SI)

“For us, this makes all the difference in a crisis situation and with regulations that require periodic screening. However, a collaborative attempt to establish comparison protocol from similar samples to validate the two technologies fails, after the epidemic.”(Technical manager)

“A first meeting then takes place with biochemists. They make me understand that although argan oil has virtues, but it contains large molecules that hardly penetrate the skin. However, in the case of cosmetics, consumers often expect products that have quick effects, are suitable for different skin types, and are adapted to the climate. Under these conditions, biochemists believe that we must first develop products which combine argan oil with synthetic excipients, therefore, not vegetable. According to biochemists, ‘Although it is possible to extract active ingredients from argan oil that ensure good penetration into the skin in specific places, it remains a technical challenge that requires a lot of money’.”(The founder and president)

“Having heard about what I did to help the cooperative, the cosmetologist then contacted me and offered to prepare, on a voluntary basis, a 100% natural cosmetic whose composition rarely exceeds the five ingredients, a record for the cosmetic industry. In fact, she told me that it costs between $25,000 and $55,000 to develop a cosmetic product. She offered to pay her when I sold my first product. To develop this cosmetic, I propose a collaboration between the biochemists and the independent cosmetologist. The involvement of these two actors strengthens the credibility of the product, which can therefore benefit from the financial support of the Business Development Bank of Canada to finalize its realization.”(The founder and president)

“The meeting is held with about sixty Berber women. Discussions mainly revolve around volumes and prices. While volumes can be assured, market-dependent prices cannot. The strong variations in the price of raw materials, which are caused by human beings, artificially increase prices by 20% each year. For me, it would be unfair to charge its variations to women who only extract an oil from a natural resource (the argan tree) of which the human being is not the creator. So, I was torn between the economics of the product and what it was emotionally for me. I decide to pay the right price to the women.”(The founder and president)

“Thereafter, I got the idea to add a component to ecological cosmetics that reflects and even justifies the sacrifice made in terms of price: cosmetics that are not only ecological, but also fair. However, to be qualified as fair, the cosmetic must pass certification processes.”(Vice-president)

“The ecological and fair cosmetics being ready, we meet the distributors of classic cosmetic products as well as ecological and fair products. With the latter, partnerships are easier. They know their business, their customers, their environmental language and above all they know how to present biocosmetic products. This is not the case with distributors of traditional cosmetics such as pharmacies. For them, the word ‘green’, ‘organic’, is not what is in their language. Rather, it’s the word, ‘high efficiency’, and the prices that count. So, we must be able to prove it to them. Which we did very well, telling them that our products are as effective if not more than what is available on the market. And in this, the certifications obtained from Ecocert and Québec Vrai help us enormously because they also certify the quality of the product.”(Vice-president)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Article Title | Date | Author | Newspaper | Number of Pages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 Juin 2003 | - | Les Affaires | 1 |

| 12 Juin 2013 | V.-P. Innovation et DD | 3 E Colloque IDP | 25 |

| 20 Mars 2013 | Pierre Turbis | Le Courrier du Sud | 2 |

| 20 Août 2012 | Pierre Pelchat | Le Soleil | 2 |

| 20 Septembre 2012 | Annie Mathieu | Le Soleil | 2 |

| 28 Août 2012 | - | TVA Interactif | 3 |

| 2 Octobre 2012 | Matthieu Boivin | Le Soleil | 2 |

| 16 Janvier 2013 | Matthieu Boivin | Le Soleil | 2 |

| 5 Septembre 2012 | - | L’Écho de Saint-Jean | 2 |

| 11 Février 2012 | Patrick Bellerose | Les Affaires, No: 6 | 2 |

| 20 Septembre 2012 | - | TVA interactif | 3 |

| 22 Novembre 2011 | - | Canada NewsWire | 1 |

| 28 Août 2012 | - | CTV News | 2 |

| 19 Septembre 2012 | - | Canada NewsWire | 2 |

| 30 Octobre 2009 | - | Canada NewsWire | 1 |

| 21 Septembre 2012 | Mathieu Boivin | Le Soleil | 1 |

Appendix B

| Article Title | Date | Author | Newspaper | Number of Pages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 Septembre 2013 | Martine Letarte | La Presse | 2 |

| 12 Juin 2013 | Vice-president | Colloque IDP | 13 |

| 1 Décembre 2007 | Pierre Théroux | Les Affaires | 3 |

| 10 Mai 2008 | Marc Gosselin | Les Affaires | 3 |

| 15 Juillet 2007 | - | Affaires—Progrès Villeray, 73(10) | 2 |

| 28 Mars 2013 | Annie Lafrance | Le Soleil | 2 |

| 14 Juin 2011 | - | La Moisson | 2 |

| 15 Mai 2013 | - | 24 Heures Montréal | 2 |

| 28 Octobre 2013 | Emilie Laperrière | La Presse | 3 |

| 2013 | Géraldine Zaccaardelli | Boutique Biosphere | 5 |

| 19 Octobre 2010 | Ève Dumas | Cyberpresse | 2 |

| 17 Juin 2013 | Boualem Hadjouti | GaïaPresse | 3 |

| 23 Décembre 2008 | Pelletier-Legros, Marie-Luce | Métro (Montréal) | 3 |

| 2 Mai 2008 | Marc Gosselin | Les Affaires | 2 |

| 20 Mai 2007 | - | Le Progrès Villeray, 73(2) | 2 |

| 1 Décembre 2009 | - | Nouvelles Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, 2(48) | 2 |

| 19 Novembre 2011 | Marie Lyan | Les Affaires No: 42 | 3 |

| 26 Juin 2007 | - | Les Affaires | 2 |

| 29 Mai 2010 | - | Les Affaires—Cahier Spécial | 3 |

| 29 Mai 2010 | Anne-Marie Tremblay | Les Affaires | 2 |

References

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future: World Commission on Environment and Development Edition; Oxford Paperbacks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-19-282080-8. [Google Scholar]

- Aka, K.G. Actor-Network Theory to Understand, Track and Succeed in a Sustainable Innovation Development Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Eco-Innovation in Industry: Enabling Green Growth: OECD Innovation Strategy; OECD: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida, J.M.G.; Gohr, C.F.; Morioka, S.N.; Medeiros da Nóbrega, B. Towards an Integrative Framework of Collaborative Capabilities for Sustainability: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Von Daniels, C.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Balkenende, A.R. A Process Model for Collaboration in Circular Oriented Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 125499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistov, V.; Aramburu, N.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J. Open Eco-Innovation: A Bibliometric Review of Emerging Research. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellano, M.; Lambey-Checchin, C.; Medini, K.; Neubert, G. A Methodological Framework to Support the Sustainable Innovation Development Process: A Collaborative Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Moggi, S.; Campedelli, B. Spreading Sustainability Innovation through the Co-Evolution of Sustainable Business Models and Partnerships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mercado-Caruso, N.; Segarra-Oña, M.; Ovallos-Gazabon, D.; Peiró-Signes, A. Identifying Endogenous and Exogenous Indicators to Measure Eco-Innovation within Clusters. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velter, M.G.E.; Bitzer, V.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Kemp, R. Sustainable Business Model Innovation: The Role of Boundary Work for Multi-Stakeholder Alignment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; McMeekin, A. An introduction: Mapping the field(s) of sustainable innovation. In Handbook of Sustainable Innovation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78811-256-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gente, V.; Pattanaro, G. The Place of Eco-Innovation in the Current Sustainability Debate. Waste Manag. 2019, 88, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, N.; Zhang, X. Evolving Theories of Eco-Innovation: A Systematic Review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 19, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.M.A.; Kovaleski, J.L.; Yoshino, R.T.; Pagani, R.N. Knowledge and Technology Transfer Influencing the Process of Innovation in Green Supply Chain Management: A Multicriteria Model Based on the DEMATEL Method. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuo, T.-C.; Smith, S. A Systematic Review of Technologies Involving Eco-Innovation for Enterprises Moving towards Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; del Río, P.; Könnölä, T. Diversity of Eco-Innovations: Reflections from Selected Case Studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Bossink, B.A.G. Firms’ Capabilities for Sustainable Innovation: The Case of Biofuel for Aviation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 1263–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, G.; Kennedy, S. Sustainability as process. In The SAGE Handbook of Process Organization Studies; Sage: London, UK, 2017; pp. 417–431. ISBN 978-1-4462-9701-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lupova-Henry, E.; Dotti, N.F. Governance of Sustainable Innovation: Moving beyond the Hierarchy-Market-Network Trichotomy? A Systematic Literature Review Using the ‘Who-How-What’ Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaget, P.; Geissdoerfer, M.; Kharrazi, A.; Evans, S. The Theoretical Foundations of Sociotechnical Systems Change for Sustainability: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 878–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemigala, M. Tendencies in Research on Sustainable Development in Management Sciences. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancino, C.A.; La Paz, A.I.; Ramaprasad, A.; Syn, T. Technological Innovation for Sustainable Growth: An Ontological Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Coenen, L. The Geography of Sustainability Transitions: Review, Synthesis and Reflections on an Emergent Research Field. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 17, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability Transitions: An Emerging Field of Research and Its Prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, B.V.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; de Medeiros, J.F. Collaboration Practices in the Fashion Industry: Environmentally Sustainable Innovations in the Value Chain. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 106, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Bocken, N.; Balkenende, R. Why Do Companies Pursue Collaborative Circular Oriented Innovation? Sustainability 2019, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, D. Implementation of Collaborative Activities for Sustainable Supply Chain Innovation: An Analysis of the Firm Size Effect. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: Towards an Integrative Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Cordeiro, J.J.; Vazquez Brust, D.A. Facilitating sustainable innovation through collaboration. In Facilitating Sustainable Innovation through Collaboration; Sarkis, J., Cordeiro, J.J., Vazquez Brust, D., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-90-481-3158-7. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, A.F.; Naveiro, R.M.; Aoussat, A.; Reyes, T. Systematic Literature Review of Eco-Innovation Models: Opportunities and Recommendations for Future Research. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 1278–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation of SMEs: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijtendijk, H.; Blom, J.; Vermeer, J.; van der Duim, R. Eco-Innovation for Sustainable Tourism Transitions as a Process of Collaborative Co-Production: The Case of a Carbon Management Calculator for the Dutch Travel Industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1222–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.M.L. Assembling Interdisciplinary Energy Research through an Actor Network Theory (ANT) Frame. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 12, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyl, B.; Vallet, F.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Real, M. The Integration of a Stakeholder Perspective into the Front End of Eco-Innovation: A Practical Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossle, M.B.; Dutra de Barcellos, M.; Vieira, L.M.; Sauvée, L. The Drivers for Adoption of Eco-Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, J.C.J.M.; Truffer, B.; Kallis, G. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions: Introduction and Overview. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, C.P.; Del Río González, P.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J. Drivers and Barriers of Eco-Innovation Types for Sustainable Transitions: A Quantitative Perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiefer, C.P.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; Del Río, P. Building a Taxonomy of Eco-Innovation Types in Firms. A Quantitative Perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, C.P.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; Del Río, P.; Callealta Barroso, F.J. Diversity of Eco-Innovations: A Quantitative Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1494–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzucchi, A.; Montresor, S. Forms of Knowledge and Eco-Innovation Modes: Evidence from Spanish Manufacturing Firms. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review: Sustainability-Oriented Innovation. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M. What Drives Eco-Innovation? A Review of an Emerging Literature. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 19, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, C.; González-Moreno, Á.; Sáez-Martínez, F.J. Eco-Innovation: Insights from a Literature Review. Innovation 2015, 17, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisetti, C.; Marzucchi, A.; Montresor, S. The Open Eco-Innovation Mode: An Empirical Investigation of Eleven European Countries. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 1080–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Zhou, X. On the Drivers of Eco-Innovation: Empirical Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.J.; Yang, C.; Sheu, C. The Link between Eco-Innovation and Business Performance: A Taiwanese Industry Context. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Medeiros, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Success Factors for Environmentally Sustainable Product Innovation: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainable Innovation: State-of-the-Art and Steps towards a Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, E.; Hidalgo, A.; Nuur, C. Diffusion of Eco-Innovations: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 33, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero, A.; Moreno-Mondéjar, L.; Davia, M.A. Drivers of Different Types of Eco-Innovation in European SMEs. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 92, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiter, T.; Hirzel, S.; Worrell, E. The Characteristics of Energy-Efficiency Measures—A Neglected Dimension. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñigo, E.A.; Albareda, L. Understanding Sustainable Innovation as a Complex Adaptive System: A Systemic Approach to the Firm. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.-H.; Roh, T.; Kim, S.; Youn, Y.-C.; Park, M.; Han, K.; Jang, E. Eco-Innovation for Sustainability: Evidence from 49 Countries in Asia and Europe. Sustainability 2015, 7, 16820–16835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gremyr, I.; Siva, V.; Raharjo, H.; Goh, T.N. Adapting the Robust Design Methodology to Support Sustainable Product Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Machiba, T. Eco-innovation for enabling resource efficiency and green growth: Development of an analytical framework and preliminary analysis of industry and policy practices. In International Economics of Resource Efficiency; Bleischwitz, R., Welfens, P.J.J., Zhang, Z., Eds.; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 371–394. ISBN 978-3-7908-2600-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.G.; Grosse-Dunker, F.; Reichwald, R. Sustainability Innovation Cube—A Framework to Evaluate Sustainability-Oriented Innovations. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2009, 13, 683–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijker, W.E.; Hughes, T.P.; Pinch, T.; Douglas, D.G. The Social Construction of Technological Systems: New Directions in the Sociology and History of Technology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-262-51760-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmidt, E.J.; de Brentani, U.; Salomo, S. Performance of Global New Product Development Programs: A Resource-Based View. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2007, 24, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, Y. New Product Development Process: A Perspective for Reexamination. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1988, 5, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmelin, H.; Seuring, S. Determinants of a Sustainable New Product Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 69, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Luo, T.; Huang, S. Product Sustainability Assessment for Product Life Cycle. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yu, S.; Tao, J. Design for Energy Efficiency in Early Stages: A Top-down Method for New Product Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendeville, S.; O’Connor, F.; Palmer, L. Material Selection for Eco-Innovation: SPICE Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4516-0247-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R.; Volpi, M. The Diffusion of Clean Technologies: A Review with Suggestions for Future Diffusion Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, S14–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, J.; Fichter, K. The Diffusion of Environmental Product and Service Innovations: Driving and Inhibiting Factors. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 64–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burritt, R.L.; Herzig, C.; Schaltegger, S.; Viere, T. Diffusion of Environmental Management Accounting for Cleaner Production: Evidence from Some Case Studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; West, J. Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-19-929072-7. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J.; Matias, J.C.O. Open Innovation 4.0 as an Enhancer of Sustainable Innovation Ecosystems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerling, E.; Purtik, H.; Welpe, I.M. End-Users as Co-Developers for Novel Green Products and Services—An Exploratory Case Study Analysis of the Innovation Process in Incumbent Firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, S51–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnam, S.; Cagliano, R.; Grijalvo, M. How Should Firms Reconcile Their Open Innovation Capabilities for Incorporating External Actors in Innovations Aimed at Sustainable Development? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 950–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Río, P.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; Könnölä, T.; Bleda, M. Resources, Capabilities and Competences for Eco-Innovation. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2016, 22, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Río, P.; Peñasco, C.; Romero-Jordán, D. What Drives Eco-Innovators? A Critical Review of the Empirical Literature Based on Econometric Methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2158–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Cousins, P.D.; Lamming, R.C. Developing Eco-Innovations: A Three-Stage Typology of Supply Networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1948–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntunen, J.K.; Halme, M.; Korsunova, A.; Rajala, R. Strategies for Integrating Stakeholders into Sustainability Innovation: A Configurational Perspective. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2019, 36, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, R.; Globocnik, D.; Perl-Vorbach, E.; Baumgartner, R.J. Open Innovation and Its Effects on Economic and Sustainability Innovation Performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purtik, H.; Arenas, D. Embedding Social Innovation: Shaping Societal Norms and Behaviors Throughout the Innovation Process. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 963–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinski, N.; Bansal, P. Short on Time: Intertemporal Tensions in Business Sustainability. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Vredenburg, H. The Challenges of Innovating for Sustainable Development. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; et al. An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarasini, S.; Linder, M. Integrating a Business Model Perspective into Transition Theory: The Example of New Mobility Services. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Truffer, B. Technological Innovation Systems and the Multi-Level Perspective: Towards an Integrated Framework. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Turning Around Politics: A Note on Gerard de Vries’ Paper. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2007, 37, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska, B. Actor-network theory. In The SAGE Handbook of Process Organization Studies; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2017; pp. 160–173. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, B. Bruno Latour and Niklas Luhmann as Organization Theorists. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Gehman, J.; Kumaraswamy, A.; Tuertscher, P. From the process of innovation to innovation as process. In The SAGE Handbook of Process Organization Studies; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2017; pp. 451–465. [Google Scholar]

- Harsanto, B.; Permana, C. Understanding Sustainability-Oriented Innovation (SOI) Using Network Perspective in Asia Pacific and ASEAN: A Systematic Review. J. ASEAN Stud. 2019, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Etzion, D.; Gehman, J.; Ferraro, F.; Avidan, M. Unleashing Sustainability Transformations through Robust Action. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiland, S.; Bleicher, A.; Polzin, C.; Rauschmayer, F.; Rode, J. The Nature of Experiments for Sustainability Transformations: A Search for Common Ground. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 169, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucuzzella, C. Creativity, Sustainable Design and Risk Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernay, A.-L.; Mulder, K.F.; Kamp, L.M.; de Bruijn, H. Exploring the Socio-Technical Dynamics of Systems Integration—The Case of Sewage Gas for Transport in Stockholm, Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 44, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Latour, B. La Science Telle Qu’elle se Fait: Anthologie de la Sociologie des Sciences de Langue Anglaise; TAP/Anthropologie des Sciences et des Techniques; La Découverte: Paris, France, 1991; ISBN 978-2-7071-1998-8. [Google Scholar]

- Callon, M. Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 32, 196–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinch, T.J.; Bijker, W.E. The Social Construction of Facts and Artefacts: Or How the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology Might Benefit Each Other. Soc. Stud. Sci 1984, 14, 399–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, H.; Rawls, A.W. Ethnomethodology’s Program: Working Out Durkheim’s Aphorism; Legacies of Social Thought Series; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7425-7898-2. [Google Scholar]

- Laasch, O. An Actor-Network Perspective on Business Models: How ‘Being Responsible’ Led to Incremental but Pervasive Change. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penteado, I.M.; do Nascimento, A.C.S.; Corrêa, D.; Moura, E.A.F.; Zilles, R.; Gomes, M.C.R.L.; Pires, F.J.; Brito, O.S.; da Silva, J.F.; Reis, A.V.; et al. Among People and Artifacts: Actor-Network Theory and the Adoption of Solar Ice Machines in the Brazilian Amazon. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, A.; Eadson, W.; Pinder, J. The Role of Actor-Networks in the Early Stage Mobilisation of Low Carbon Heat Networks. Energy Policy 2016, 96, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fatimah, Y.A.; Raven, R.P.J.M.; Arora, S. Scripts in Transition: Protective Spaces of Indonesian Biofuel Villages. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 99, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, R.P.J.M.; Verbong, G.P.J.; Schilpzand, W.F.; Witkamp, M.J. Translation Mechanisms in Socio-Technical Niches: A Case Study of Dutch River Management. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2011, 23, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-Level Perspective and a Case-Study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van de Ven, A.H.; Angle, H.L.; Poole, M.S. Research on the Management of Innovation: The Minnesota Studies; OUP E-Books; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-19-513976-1. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A.; Tsoukas, H. Introduction: Process thinking, process theorizing and process researching. In The SAGE Handbook of Process Organization Studies; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-6556-9. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A.; Abdallah, C. Templates and turns in qualitative studies of strategy and management. In Research Methodology in Strategy and Management; Bergh, D.D., Ketchen, D.J., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2011; Volume 6, pp. 201–235. ISBN 978-1-78052-026-1. [Google Scholar]

- Siggelkow, N. Persuasion With Case Studies. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Rispal, M.H.; Bonniol, J.J. Analyse Des Données Qualitatives; Méthodes en Sciences Humaines; De Boeck Supérieur: Paris, France, 2003; ISBN 978-2-7445-0090-9. [Google Scholar]

- Thietart, R.A. Méthodes de Recherche en Management, 4th ed.; Stratégie Master; Dunod: Paris, France, 2014; ISBN 978-2-10-071702-6. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof, B.; Thiell, M. Collaboration Capacity for Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Mexico. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 67, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D. Mainstreaming Green Product Innovation: Why and How Companies Integrate Environmental Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrich, M.; Callon, M.; Latour, B. Sociologie de La Traduction: Textes Fondateurs; Collection Sciences Sociales; Ecole des Mines de Paris: Paris, France, 2006; ISBN 978-2-911762-75-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, R.K.; Piore, M.J. Innovation—The Missing Dimension; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-674-04010-6. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, D.; Diehl, J.C.; Molenaar, N. Innovation Process of New Ventures Driven by Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Applied Social Research Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-6099-1. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. “What’s the story?” Organizing as a mode of existence. In Agency without Actors? Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 163–177. ISBN 978-0-203-83469-5. [Google Scholar]

- Paschen, J.-A.; Ison, R. Narrative Research in Climate Change Adaptation—Exploring a Complementary Paradigm for Research and Governance. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B.; Mauguin, P.; Teil, G. Une méthode nouvelle de suivi des innovations: Le graphe sociotechnique. In La Gestion de la Recherche: Nouveaux Problèmes, Nouveaux Outils; De Boeck: Paris, France, 1991; pp. 419–567. [Google Scholar]

- Reficco, E.; Gutiérrez, R.; Jaén, M.H.; Auletta, N. Collaboration Mechanisms for Sustainable Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 1170–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Chittipeddi, K. Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation. Strat. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R.L.; Weick, K.E. Toward a Model of Organizations as Interpretation Systems. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Star, S.L.; Griesemer, J.R. Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–1939. Soc. Stud. Sci 1989, 19, 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions/Characteristics | Definition of the Dimensions/Characteristics | Authors of the Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Five SI dimensions. | Operational, collaborative, organizational, instrumental and holistic. | [52] |

| Three dimensions, nine characteristics and three levels of SOI. | Innovation objective, innovation outcome, and innovation relationship to the firm at operational and system levels (societal change). | [41] |

| Four dimensions and twelve characteristics. | Capacity, supportive environment, activity, and performance. | [53] |

| Three dimensions: ECORE. | Eco-innovation (inputs and demands from potential innovation partners, LCA actors, and stakeholders), quality management (assessment of derived value based on stakeholders’ requirements and acceptances), and LCA. | [54] |

| Five behavior dimensions/three SI types. | Level of interactions (low, medium, and high) leads to three degrees of SI types (incremental, limited radical, and radical). | [31] |

| Three dimensions: sustainable business model. | Value proposition, value configuration, and value distribution. | [48] |

| Three dimensions. | Target, mechanism, and impact dimensions. | [55] |

| Four dimensions and eight characteristics. | Design, user, product–service, and governance dimensions. | [16] |

| Three dimensions and twenty-seven characteristics: sustainability innovation cube (SIC). | Target (environmental, social, and economic effects), type (technology, product–service system, and business model), and lifecycle dimensions (manufacture, use, and end-of-life phases). | [56] |

| Dimension | Definition | Characteristic | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | From an environmental perspective, there are two different design rationales to SI: redesigning human-made systems to reduce their environmental impacts versus the search for minimization of those impacts. When these two perspectives are combined with the degree of compatibility/rupture of SIs with the established techno-economic system, three different approaches can be proposed to identify the role and impacts of SI. | Component addition | Development of additional components to minimize negative impacts without necessarily changing the processes/system that generate those impacts, as with “end-of-pipe” technologies. |

| Subsystem change | Eco-efficient solutions and the optimization of subsystems, leading to a reduction of negative environmental impacts. | ||

| System change | It involves the redesign of systems towards eco-effective solutions, remodeling the environmental impacts on the ecosystem and society at large. | ||

| User | All innovations target certain markets. Apart from economic demands, SIs also cover sustainability issues. Firms can learn about both by engaging with current and potential users. | Development | Identification of users that can provide valuable inputs in innovation projects. |

| Acceptance | Understanding user needs and wants enhances the market success of sustainable solutions. | ||

| Product–service | A “product–service system” provides value to customers through a “function” combining products and services targeted at specific needs. These systems are embedded in business models and comprise sustainability aspects. The more radical a SI is, the greater the change in the underlying “product service system”, including production, delivery, consumption, and disposal activities within a network. | Deliverable | Consists of changes in the product/service and value delivered and changes in the perception of the customer relations. |

| Process | Consists of changes in the value-chain process and relations that enable the delivery of the product–service and value capture. | ||

| Governance | The more radical and systemic the SIs are, the higher the likelihood that stakeholders beyond the boundaries of the firm will be involved. The growing importance of knowledge-related cooperation has recently been stressed. Firm governance is required in order to overcome potential obstacles and to renew and maintain cooperative relationships with all stakeholders. Firm governance can also fulfill social expectations of firm behavior. | Governance change | Changes in rules, norms, and values, which potentially renew the company’s structure and the managers’ relationships with economic, environmental, and social stakeholders. |

| Translation Moments | Collaborative Mechanisms | Manager’s Role |

|---|---|---|

| Problematization: consists in identifying actors’ nature and interests, preferences, demands, or individual issues. | How to become indispensable? The innovator formulates a priori the issue and his solution. This formulation implicitly defines who is concerned and why. The innovator finds the actors, who may have an interest in getting on the solution, proposed to resolve the problem. | Becoming indispensable to other actors by defining the nature and the issues of the latter, and then suggesting that the innovation would resolve the actors’ concerns or join their demands. |

| Interessement: consists in defining obligatory passage points (any material or immaterial devices by which each ally should inevitably go through if they want to solve their obstacles/problems and achieve their own interests), which are a part of innovation characteristics. | How to lock into process? The innovator locks allies through different mechanisms, sometimes by breaking other relationships that these allies had with others. The success of interessement confirms the validity of the problematization and the alliance it implies. | Locking the other actors into the roles that had been proposed for them in the innovation development. |

| Enrolment: consists in assigning different explicit or implicit roles, which facilitate the sociotechnical development of the innovation. | How to define and coordinate the roles? The innovator stabilizes the process as well as technical and social characteristics of the innovation by assigning roles to the actors according to their resources and capabilities. | Defining and interrelating the various roles he had allocated to others. Enrolment is a successful interessement. |

| Mobilization: consists in recruiting new allies, especially spokesmen or intermediaries that legitimately represent other humans, nonhumans, or artefacts by their credibility, reputation, or expertise. | How to mobilize representative spokesmen? The innovator extends the already established network during enrolment with new representatives’ allies. This is necessary because, as with the description of interessement and enrolment, only a few allies are involved. | Ensuring that supposed spokesmen for various relevant collectivities were properly able to represent those collectivities and not betrayed by the latter. |

| SI Case | Creation | Size | Sector | Participants | Time of Interview | Documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legionella Preventive Treatment (LPT) | 1965 | 115 | Treatment of industrial wastewater | V.-P. Sustainability innovation | 1 h (telephone), 4 h (face-to-face) | 10 (private) 16 (public) 01 (video) |

| V.-P. Communication | 2 h (face-to-face) | |||||

| Technical manager | 2 h (face-to-face) | |||||

| Sustainability manager | 2 h (face-to-face) | |||||

| Total | 4 | 11 h | 27 | |||

| Fair Biocosmetic (FBC) | 2005 | 22 | Cosmetics | Founder and president | 1 h (telephone), 4 h (face-to-face) | 15 (private) 20 (public) 02 (video) |

| Vice-president | 2 h (face-to-face) | |||||

| Total | 2 | 7 h | 37 | |||

| Step | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Manager’s script | ||

| A to Z | Actors involved in the SI process. They follow an alphabetical order indicated in a box, on a horizontal line, and a brief description. | The association (or substitution) connects previous and new actors to the SI. Actors can leave the process and they are replaced (substitution) or not by new actors. |

| 1 to n | SI transformations or versions that follow a numeric order indicated in a bubble and on a vertical line. | All change stemming from critical events leads to a new version of the SI. |

| Symbol // | At the end of each statement, the symbol indicates a brief description of critical event or difficulty about the process (e.g., tension, controversy, skepticism, lack of resources). | The presence of difficulty interrupts the association of actors and leads to a new version of the SI. |

| 2. Indicators of the translation process | ||

| Nn | New actor: actor recruited during the transition from one version to another. | The greater the number of new recruited actors, the more irreversible the SI. Ideally, the number of new actors should show a steady increase. |

| An | Ally: actor maintained in each version of the SI. | The greater the number of allies, the more attractive the SI is. Ideally, the number of allies should show a steady increase. |

| En | Project exploration index: E is obtained by considering the rank of the letters in alphabetical order. | The number of actors that have at least once been mobilized in the SI process. Some SIs are more attractive if they mobilize many new actors through the process. |

| ANAn | Aggregate of new actors: number of new actors mobilized. | The degree of the attachment of new actors who move from the indicator Nn to the indicator An+1. Ideally, the number of new aggregated actors should show a steady increase. |

| LNAn | Lost new actors: number of new lost actors. | The degree of the defection of new actors who leave the process. |

| 3. Index of the translation process | ||

| Sn = An + Nn | Size of the network: sum of allied and recruited actors for each version. | The greater the number of allies and new actors, the more the network solidifies. Ideally, the size should show a steady increase. |

| INn = Nn/Sn | Index of negotiation: IN takes values between 0 and 1. | If the ratio is high, it indicates that few new actors are being retained throughout the SI process. A stable SI should require only minimal reconfiguration or renegotiation of its characteristics as it spreads in time and space. Ideally, IN should show a steady decline. |

| Rn = An/Sn−1 | Index of reality: R takes values between 0 and 1. | The ratio compares the number of actors retained from the previous statement to the total number of actors in the present one. Ideally, R should remain consistently high throughout the SI process, which means the robustness of the SI project. |

| Yn = [Σ ANA − Σ LNA]/En | Index of yield: Y takes values between 1 and –1. | The capacity of the SI to attach itself to an increasing number of actors without losing them in the process. Ideally, Y should be consistently high and/or positive and increasing through the process. |

| SI Characteristics | LPT | FBC |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Component addition: includes an analysis and screening service in 24 h, a disinfection program with ecological products, and service of counselling to prevent the bacteria. | Component addition: the FBC replaces synthetic excipient (parabens) by vegetable excipient (argan oil); biodegradable packaging; fair trade with women’s cooperative from Morocco. |

| Subsystem (eco-efficient solution): by using a new technological process to treat the Legionella, the LPT introduces change in the industry. | Subsystem (eco-efficient solution): the FBC integrates the whole process, as the processing used to obtain molecules is different from those used in the synthetic cosmetic industry, and the company reuses the packaging in the production process. | |

| System (eco-effective solution): by changing radically the duration of the analysis (24 h vs. 2 weeks), and the way to treat the bacteria (prevention and use of non-toxic product), the LPT contributes to the public health system. | System (eco-effective solution): the FBC follows a fair-trade approach in which biodegradable packaging becomes input for the production process of the company, and raw materials for other industries, and has no negative impacts on human health. | |

| User | User development: R&D partnership with a professor help to develop the process-service. However, the employees are opposed to LPT because it changes the way of working. | User development: women’s cooperative, biochemists, and a cosmetologist work with the company. |

| User acceptance: such as the Public Health Service of Quebec, owners of cooling towers (consumers), including companies, are not obliged to use LPT. They prefer using the standard solution. | User acceptance: demand from consumers sensitive to ecological aspects. Other consumers do not make differences between ecological and synthetic cosmetics. | |

| Product–service | Product–service deliverable: the company does not only make analyses in 24 h and treatments with non-toxic products. It also offers a service of counselling to prevent the bacteria from growing and looks after cooling towers. | Product–service deliverable: the company transforms its business from selling cosmetics to offering a service including discounts and bonuses to bring back empty packaging and the reuse of this packaging. |

| Product–service process: the LPT changes the value chain process for treating the bacteria and requires a change in the maintenance of cooling towers, which prevents the appearance of the bacteria. | Product–service process: the FBC includes the entire supply chain during the production, consumption, customer service, and post-disposal of products. As a fair-trade product–service, it is certified by Ecocert and Quebec Vrai. | |

| Governance | To become a standard in the industry, the use of the LPT requires the passing of a law by the members of parliament. | Argan price variations also depend on the market and makes it difficult to negotiate with women’s cooperatives. |

| Translation | LPT | FBC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moment | Collaborative mechanisms | Target characteristic | Collaborative mechanisms | Target characteristic |

| Problematization | After business travel in France, the manager (V.-P., Sustainable Innovation) notes that there is no regulation in Quebec to prevent the Legionella, which caused deaths in many European countries. The LPT (in its initial version) could be the best solution to Legionella in Quebec compared to the standard solution. | Component addition: the initial version of the LPT includes an analysis in 24 h and a service of counselling to prevent the bacteria. | Through an international cooperation internship in Morocco, the manager (founder) decides to help a women’s cooperative threatened with losing their argan oil activity by buying their production. Back in Quebec, the manager thinks that she could use the argan oil to develop a biocosmetic. The biocosmetics could be a best solution compared to synthetic cosmetics. | Component addition: the initial version of FBC will include argan oil, a vegetable excipient extracted from argan tree, which is not harmful for humans. |

| Interessement | The company has no sufficient resources (expertise and money) to invest in a new laboratory for developing the LPT. | Component addition: adding of a disinfection program with ecological product. | The managers have no resources (expertise and money) to develop the biocosmetic and finds a biochemist’s company to work with them. | Component addition: combination of the argan oil with the paraben. This combination will improve the efficiency of the biocosmetics according to the biochemist. |

| The technical manager works with a professor interested in the project linking to his research interests. The latter helps the company to find money (from a research subsidy) and suggests improving the sustainability characteristics of the LPT. | User development: R&D partnership with a professor will help to develop the LPT. | A financial institution agrees to invest in the project if the biochemists’ company is associated and argan oil can be supplied regularly from Morocco to Quebec. The manager decides to collaborate with a cosmetologist (expert in vegetable excipient such as argan oil). A collaboration between the biochemists and the cosmetologist could be beneficial for each party in terms of expertise exchange. | User development: financial and R&D partnership with the financial institution, the biochemists and the cosmetologist | |

| The V.-P., Sustainable Innovation, also tries to attract an association of owners of cooling towers. | User acceptance: such as the public health service, owners of cooling towers prefer using the standard solution rather than the LPT. | To interest consumers, the company also improves the sustainability characteristics of the FBC. | Product–service deliverable: the company transforms its business from selling cosmetics to offering a service including discounts and bonuses to bring back empty packaging and the reuse of this packaging. | |

| Enrolment | Employees refuse to be enrolled as developers in the project because it changes the way of working. The technical manager and the professor are the producers of the LPT in the new laboratory. A sustainability manager position is also created for promoting the LPT. | Product–service process: the technical manager reassures them that the development of the LPT will, on the contrary, improve their capacities. | The biochemists and the cosmetologist collaborate (as producers) to develop an efficient biocosmetic. As the provider of the argan oil, the women’s cooperative wants to charge the company at the right price (higher than the market price). | Component addition: the FBC will be an efficient biocosmetic only made with 100% argan oil. |

| Mobilization | Before the epidemic, the V.-P. of Communication and the sustainability manager mobilize the members of parliament to pass a law, as well as the public health service, the Quebec Building Authority, the media, and the association for innovation in chemistry to support this idea. Thereafter, a Legionella epidemic will appear in the province, causing deaths. | Governance: although the LPT have been used during the epidemic, it fails to become an industry standard because that requires the passing of a law by the members of parliament. The members of parliament refuse to take a new law. The public health service refuses to support, because of the existence of the standard solution. | To keep the women mobilized into the project, the manager agrees to pay the right price. This approach will be valued in the biocosmetic by certifications (Ecocert and Quebec Vrai). | Product–service process: the FBC includes the entire supply chain during the production, consumption, customer service, and post-disposal of products. As a fair-trade product–service, it is certified Ecocert and Quebec Vrai. |

| Version | LPT | FBC | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Indicator | Index | Indicator | Index | ||||||||||||||

| N | A | E | ANA | LNA | S | IN | R | Y | N | A | E | ANA | LNA | S | IN | R | Y | |

| (1) | - | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| (2) | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.25 | - | 0.00 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.66 | - | 0.25 |

| (3) | 2 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0.40 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| (4) | 3 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 0.71 |

| (5) | 1 | 7 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.36 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0.28 | 0.71 | 0.55 |

| (6) | 3 | 8 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 0.27 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.72 |

| (7) | 3 | 10 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 0.23 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 3 | 10 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.78 |

| (8) | 5 | 9 | 19 | 5 | 4 | 14 | 0.35 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 2 | 13 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 15 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| (9) | 2 | 11 | 19 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 0.15 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 2 | 15 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.83 |

| (10) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 17 | 22 | 4 | 0 | 21 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.86 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aka, K.G.; Labelle, F. The Collaborative Process of Sustainable Innovations under the Lens of Actor–Network Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910756

Aka KG, Labelle F. The Collaborative Process of Sustainable Innovations under the Lens of Actor–Network Theory. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910756

Chicago/Turabian StyleAka, Kadia Georges, and François Labelle. 2021. "The Collaborative Process of Sustainable Innovations under the Lens of Actor–Network Theory" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910756

APA StyleAka, K. G., & Labelle, F. (2021). The Collaborative Process of Sustainable Innovations under the Lens of Actor–Network Theory. Sustainability, 13(19), 10756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910756