A Framework of Engagement Practices for Stakeholders Collaborating around Complex Social Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Part 1: Exploring and Identifying the Core Theoretical Concepts

2.2. Part 2: Framework Development: The Preliminary Framework

2.3. Part 3: Framework Evaluation: Towards an Enhanced Framework

- Who are the target beneficiaries and who do you partner with?

- Is there a need for guidelines or frameworks to assist in managing stakeholder relationships, and do they exist?

- What are important considerations for managing stakeholder relationships in a stakeholder network?

- Do you agree with the stakeholder engagement themes and the principles contained in the framework?

- Are they appropriate to your context?

3. Literature Review (Part 1): Exploring and Identifying the Core Theoretical Concepts

3.1. Conceptual Review of Innovation Platforms

3.2. Concepts from the Systematized Literature Review: Towards a Preliminary Framework

4. Preliminary Framework (Part 2): An Inventory of Implementation Principles

5. Results and Discussion (Part 3): Evaluation and Evolution of the Framework

5.1. Insights from the Interviews

5.1.1. Stakeholders Present in South Africa’s Initiatives to Empower the Marginalised

5.1.2. The Evolutionary Nature of Development Initiatives

5.1.3. Relative Importance of Engagement Practices

5.1.4. Stakeholder Identification Practice

5.1.5. The Content of the Framework

5.2. Practical Application: The Case Study

5.2.1. Results from the Case Study

Issue 1: Formal Versus Informal Network Processes

Issue 2: Lack of Skills Necessary to Market the IP’s Interventions

Issue 3: Avoiding the Duplication of Efforts

Issue 4: Stakeholders’ Expectations Are Mismatched

5.2.2. Recommendations for Improved Engagement Developed from the Framework

Recommendation for Issue 1: Formalising the Network without Disregarding the Value of Informal Processes

Recommendation for Issue 2: Identify and Integrate a “Marketing Champion”

5.2.3. Reflections from the Case Study

5.3. Framework Evolution: Addressing the Gaps

6. Conclusions

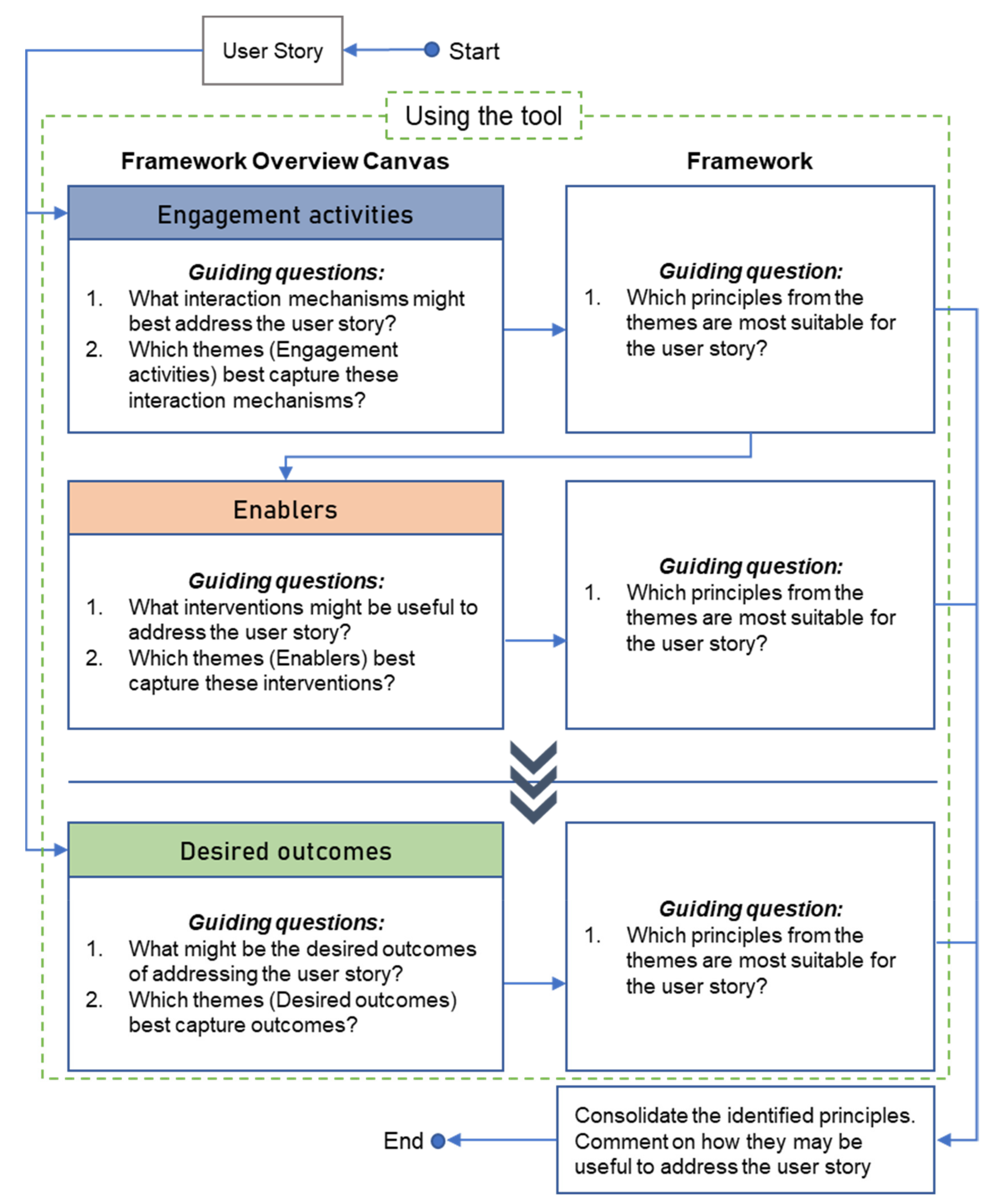

6.1. Enhanced Framework and Management Tool

6.2. Concluding Remarks

- A more thorough investigation of the common barriers to stakeholder engagement and how to overcome them would benefit the research domain. It may inform the appropriate additions to the conceptual framework for stakeholder engagement in IPs.

- The final conceptual framework and the overall management tool for stakeholder engagement in IPs may be improved by including recommendations for “how” its implementation principles may be addressed.

- Future research might consider when to engage stakeholders. This may require an investigation into the different IP lifecycle phases and the needs of the IP at these different stages. This may be a complex investigation as IPs are diverse and may have several lifecycle phases.

- The impact of cognitive biases on decision-making and the consequences of unchecked biases on stakeholder engagement need further investigation.

- The case study did not consider an IP where the marginalised stakeholders and beneficiaries of the intervention are direct participants. Future research should identify case studies where this is the case.

- Drawing from the previous point, further investigations into the conditions which warrant the exclusion of the beneficiaries as participants in the innovation process are required. They may include considering who makes the decision as to who has the right or possibility to participate.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Search Terms | Search Position | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search string 1 | Innovation platforms | “innovation platforms” | “multi-stakeholder partnerships” | Title, abstract, keywords |

| Developing countries | “developing country” | “developing countries” | Title, abstract, keywords | |

| Search string 2 | Innovation platforms | “innovation platforms” | “multi-stakeholder partnerships” | Title, abstract, keywords |

| Actor | “actor” | “participant” | Title, Abstract, Keywords | |

| “stakeholder” | “player” | |||

| Role/responsibility | “role” | “responsibility” | Title, Abstract, Keywords | |

| “task” | “function” | |||

| Search string 3 | Innovation platforms | “innovation platforms” | “multi-stakeholder partnerships” | Title, Abstract, Keywords |

| Innovation for inclusive development | “innovation for inclusive development” | “inclusive innovation” | Title, Abstract, Keywords | |

| “frugal innovation” | “responsible innovation” | |||

| “inclusion” | “base-of-the-pyramid” | |||

Appendix B

| Participant Profile | Qualifications and Experience | |

|---|---|---|

| First-pass interview | The pharmaceutical services manager at a not-for-profit organisation (NPO) specialising in clinical care and treatment services and health and community systems strengthening, the interviewee has over 17 years’ experience in South Africa’s pharmacy industry. The organisation is a leader in public health innovation and facilitates direct programme implementation and technical assistance for the South African Government and the interviewee manages several of these programmes. They work closely with many stakeholders, including local, regional and national government and local marginalised communities. | The interviewee holds a Bachelor’s degree in Pharmacy, a Certificate in Advanced Health Management (Yale University in collaboration with the Foundation for Professional Development’s Business School) and a Master of Science degree in Global Health (Northwestern University). |

| Evaluation interviews | Interviewee 1 is a cofounder and director of a well-established NPO and research organisation conducting innovative research to strengthen public engagement in many of South Africa’s health research projects. The interviewee has a passion to see marginalised communities empowered using innovative participatory approaches, including visual participatory methods and action-orientated approaches. They have many years of experience working with over-researched communities and navigating the dynamics that are associated with the participation of marginalised individuals. The interviewee believes that their approach to research should be accessible to others to learn from, improving engagement practices and policy-making. | The interviewee holds a PhD in Immunology and Genetics (University of Cambridge). They have held several research positions both in the United Kingdom and in South Africa. |

| Interviewee 2 is an expert in community informatics, specialising in collaborative communities. They have experience in both academic and research and development (R&D) contexts and consult for a variety of communities, organisations and interorganisational networks in both the developing and the developed world. Their services include community visioning and innovation strategy advice, community network mapping, collaborative sense-making and project management. The interviewee adopts an ecosystems perspective coupled with an innovative stakeholder mapping approach to understand the dynamics of stakeholder networks. | The interviewee holds a PhD in Information Management (Tilburg University). They held several research positions in both the academic and the private sector before starting their own business, an applied research consultancy on collaborative communities. | |

| Interviewee 3 has experience developing volunteer networks in a diverse range of contexts in both the developed and the developing world. They piloted a volunteer platform in a marginalised community in the Western Cape. They have a novel approach to incentivising volunteering to realise tangible community impact and social development. Their passion for people and technology is combined in an innovative way to realise transformative social impact in marginalised communities. The insight they have into the importance of the initial rollout phases of development initiatives and the stakeholder dynamics associated with the early adoption and dissemination of interventions proved very attractive to inform this research. | The interviewee holds qualifications in Computer Science (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and has founded and cofounded several innovative platforms leveraging technology to relieve social and economic disparity in South Africa. | |

| Interviewee 4 is an independent consultant and founder and managing director of an NPO with a vision to provide holistic support to the poor by facilitating the collaboration of other NPOs and channelling crowd efforts. Their experience as a champion to facilitate the collaborative efforts of NPOs within a single community places them at the centre of a larger stakeholder network. Their experience managing on-the-ground issues was attractive to inform the research. Their approach to empower a very marginalised part of society, those living at the BOP and suffering from the realities of homelessness provided important insight into the dynamics of participatory mechanisms aimed at these members of society. | The interviewee holds a Bachelor’s degree in Industrial Engineering and has industry experience in management consulting and entrepreneurship. |

Appendix C

| PoE | Implementation Principles |

|---|---|

| Action |

|

| Alignment |

|

| Championing |

|

| Communication |

|

| Conflict management | IP’s participants are encouraged to continuously discount self-interests and to focus on collaboration |

| Facilitation |

|

| Gender and racial dynamics |

|

| Managing power dynamics |

|

| Monitoring, evaluation and feedback |

|

| Participation |

|

| Resources and capacity |

|

| Shared learning |

|

| Strategic representation |

|

| Transparency |

|

| Trust building |

|

| Visioning and planning |

|

Appendix D

| PoE Theme | Implementation Principles |

|---|---|

| Engagement activities | |

| Communication |

|

| Conflict management |

|

| Managing gender and racial dynamics |

|

| Managing power dynamics |

|

| Transparency |

|

| Trust building |

|

| Enablers | |

| Facilitation |

|

| Monitoring, evaluation and feedback |

|

| Rolldown of participation |

|

| Strategic representation |

|

| Visioning and planning |

|

| Desired outcomes | |

| Alignment |

|

| Championing |

|

| Implementation of interventions |

|

| Participation |

|

| Resources and capacity |

|

| Shared learning |

|

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. FOCUS: Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/pages/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Jatana, N.; Currie, A. Hitting the Targets—The Case for Ethical and Empowering Population Policies to Accelerate Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals; Population Matters: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. The Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/hia/evidence/doh/en/ (accessed on 4 June 2019).

- Govender, J. Social justice in South Africa. Civ. Rev. Ciências Sociais 2016, 16, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, V.; Schaay, N.; Schneider, H.; Sanders, D. Addressing social determinants of health in South Africa: The journey continues. South. Afr. Health Rev. 2017, 2017, 77–87. Available online: https://www.hst.org.za/publications/SouthAfricanHealthReviews/8_AddressingsocialdetermininantsofhealthinSouthAfrica_thejourneycontinues.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2019).

- Rispel, L.; Setswe, G. Stewardship: Protecting the Public’s Health. S. Afr. Health Rev. 2007, 1, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lorraine, M.M.; Molapo, R.R. South Africa’s Challenges of Realising Her Socio-Economic Rights. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mehlomakulu, B. Lack of Government Coordination Robs South Africa of Economic Transformation. Available online: https://www.sabs.co.za/media/docs/Lack-of-government-coordination.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Van der Westhuizen, M.; Swart, I. The struggle against poverty, unemployment and social injustice in present-day South Africa: Exploring the involvement of the Dutch Reformed Church at congregational level. STJ Stellenbosch Theol. J. 2015, 1, 731–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Killander, M. Criminalising homelessness and survival strategies through municipal by-laws: Colonial legacy and constitutionality. S. Afr. J. Hum. Rights 2019, 35, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homann-Kee Tui, S.; Adekunle, A.; Lundy, M.; Tucker, J.; Birachi, E.; Schut, M.; Klerkx, L.; Ballantyne, P.; Duncan, A.; Cadilhon, J.; et al. What Are Innovation Platforms? Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/34157/Brief1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- Duncan, A.J.; Le Borgne, E.; Maute, F.; Tucker, J. Impact of Innovation Platforms. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/34271/Brief12.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- Tucker, J.; Schut, M.; Klerkx, L. Linking Action at Different Levels through Innovation Platforms. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/34163/Brief9.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Van Rooyen, A.; Swaans, K.; Cullen, B.; Lema, Z.; Mundy, P. Facilitating Innovation Platforms. Innovation Platforms Practice Brief. 10. 2013. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/34164/Brief10.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Grobbelaar, S.S. Developing a local innovation ecosystem through a university coordinated innovation platform: The University of Fort Hare. Dev. South. Afr. 2018, 35, 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jabareen, Y. Building a Conceptual Framework: Philosophy, Definitions, and Procedure. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlmann, F.R.P.; Grobbelaar, S.S. Identifying practices of engagement in innovation platforms: Towards understanding innovation platforms in healthcare. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Johannesburg, South Africa, 29 October–1 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Software Development GmbH, What Is Atlas.ti? 2019. Available online: https://atlasti.com/product/what-is-atlas-ti/ (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.,: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Research in Education: A Conceptual Introduction, 3rd ed.; HarperCollins College Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Research Methodology: Business and Management Contexts, 7th ed.; Oxford University Press Southern Africa (Pty) Ltd.: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bless, C.; Higson-Smith, C.; Sithole, L. Fundamentals of Social Research Methods: An. African Perspective, 5th ed.; Juta and Company (Pty) Ltd.: Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research: Perspectives on Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marais, A.; Grobbelaar, S.S.; Meyer, I.; Kennon, D.; Herselman, M. Supporting the formation and functioning of innovation platforms in healthcare value chains. Sci. Public Policy 2021, 48, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schut, M.; Klerkx, L.; Sartas, M.; Lamers, D.; Mc Campbell, M.; Ogbonna, I.; Kaushik, P.; Atta-Krah, K.; Leeuwis, C. Innovation Platforms: Experieces with their Institutional Embedding in Agricultural Research for Development. Exp. Agric. 2016, 52, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.; Tucker, J.; Snyder, K.; Lema, Z.; Duncan, A. An analysis of power dynamics within innovation platforms for natural resource management. Innov. Dev. 2014, 4, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaans, K.; Boogaard, B.; Bendapudi, R.; Taye, H.; Hendrickx, S.; Klerkx, L. Operationalizing inclusive innovation: Lessons from innovation platforms in livestock value chains in India and Mozambique. Innov. Dev. 2014, 4, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, C.; Lawrence, T.B.; Grant, D. Discourse and collaboration: The role of conversations and collective identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei-Nsiah, S.; Klerkx, L. Innovation platforms and institutional change: The case of small-scale palm oil processing in Ghana. Cah. Agric. 2016, 25, 65005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Acheampong, R.; Jiggins, J.; Quartey, E.T.; Karikari, N.M.; Jonfia-Essien, W.; Quarshie, E.; Osei-Fosu, P.; Amuzu, M.; Afari-Mintah, C.; Ofori-Frimpong, K.; et al. An innovation platform for institutional change in Ghana’s cocoa sector. Cah. Agric. 2017, 26, 35002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiggins, J.; Hounkonnou, D.; Sakyi-Dawson, O.; Kossou, D.; Traoré, M.; Röling, N.; van Huis, A. Innovation platforms and projects to support smallholder development- experiences from Sub-Saharan Africa. Cah. Agric. 2016, 25, 64002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, A.; Grobbelaar, S.S.; Kennon, D. A conceptual framework towards the development of Innovation Platforms that facilitate the integration of technology in healthcare value chains. In Proceedings of the International Association for Management of Technology (IAMOT) 2017, Vienna, Austria, 14–18 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marais, A. A Management Tool towards the Development of Healthcare Innovation Platforms. Ph.D. Thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marais, A.; Grobbelaar, S.S.; Kennon, D. A conceptual framework for managing healthcare innovation platforms: A value chain perspective. In Proceedings of the International Association for Management of Technology (IAMOT) 2018, Birmingham, UK, 22–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dondofema, R.; Grobbelaar, S.S. A methodology for case study research to analyse innovation platforms in South African healthcare sector. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Johannesburg, South Africa, 29 October–1 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dondofema, R.A.; Grobbelaar, S.S. Conceptualising innovation platforms through innovation ecosystems perspective. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Valbonne, France, 17–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ngongoni, C.N.; Grobbelaar, S.S.; Schutte, C.S. Platforms in the Healthcare Innovation Ecosystems: The Lens of an Innovation Intermediary. In Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE S.A. Biomedical Engineering Conference, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 4–6 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ngongoni, C.N.; Grobbelaar, S.S.; Schutte, C.S. Event Structure Analysis as a Tool for Investigating Sustainability in Innovation Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technology Management, Operations and Decisions (ICTMOD) (Virtual conference), Marrakech, Morocco, 24–27 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ngongoni, C.N.; Grobbelaar, S.S. Creation in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Learnings from a Norwegian perspective. In Proceedings of the IEEE Africon 2017, Cape Town, South Africa, 18–20 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ngongoni, C.N.; Grobbelaar, S.S.; Schutte, C.S. Making Sense of the Unknown: Using Change Attractors to Explain Innovation Ecosystem Emergence. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Poutanen, P. Success factors of innovation ecosystems—Initial insights from a literature review. In CO-CREATE 2013 -The Boundary-Crossing Conference on Co-Design in Innovation; Smeds, R., Irrmann, O., Eds.; Aalto University: Espoo, Finland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Merwe, M.D.; Grobbelaar, S.S.; Schutte, C.S.; von Leipzig, K.H. Towards an enterprise growth framework for entering the Base of the Pyramid (BoP) market. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2018, 15, 1850035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hart, S.L. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Strategy + Bus. 2002, 1, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, I.; Robey, J. What is the Opportunity for Companies at the Bottom of the Pyramid? 2016. Available online: http://www.eighty20.co.za/bottom-of-the-pyramid/ (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Statistics South Africa. Poverty Trends in South. Africa: An. Examination of Absolute Poverty between 2006 and 2015; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017.

- Foster, C.; Heeks, R. Conceptualising Inclusive Innovation: Modifying Systems of Innovation Frameworks to Understand Diffusion of New Technology to Low-Income Consumers. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2013, 25, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, P. How effective is inclusive innovation without participation? Geoforum 2016, 75, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyet, V.; Schlaepfer, R.; Parlange, M.B.; Buttler, A. A framework to implement Stakeholder participation in environmental projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 111, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, D.R.; Hayes, L.; Unwin, N.C. Diabetes in Africa. Challenges to health care for diabetes in Africa. J. Cardiovasc. Risk 2003, 10, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edlmann, F.R.P.; Grobbelaar, S.S. The preliminary validation of practices of engagement in innovation platforms: Towards understanding innovation platforms in healthcare. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Antibes, France, 17–19 June 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pigford, A.-A.E.; Hickey, G.M.; Klerkx, L. Beyond agricultural innovation systems? Exploring an agricultural innovation ecosystems approach for niche design and development in sustainability transitions. Agric. Syst. 2018, 164, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellbrock, W.; Knierim, A. Unravelling Group Dynamics in Institutional Learning Processes. Outlook Agric. 2014, 43, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawde, N.C.; Sivakami, M.; Babu, B.V. Building Partnership to Improve Migrants’ Access to Healthcare in Mumbai. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kefasi, N.; Oluwole, F.; Adewale, A.; Gbadebo, O. Promoting effective multi-stakeholder partnership for policy development for smallholder farming systems: A case of the Sub Saharan Africa challenge programme. African J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 3451–3455. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.; Nixon, L.; Baker, R. Moving research to practice through partnership: A case study in Asphalt Paving. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2015, 58, 824–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobbelaar, S.S.; Schiller, U.; de Wet, G. University-supported inclusive innovation platform: The case of university of Fort Hare. Innov. Dev. 2017, 7, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, N.R.; Swart, J. Building a roundtable for a sustainable hazelnut supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1398–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, P.; Dziegielewska-Geitz, M.; Schouten, T.; Butterworth, J.; Verhagen, J.; Manning, N.; Da Silva, C.; Bury, P.; Sutherland, A.; Batchelor, C.; et al. Building more effective partnerships for innovation in urban water management. In Water and Urban Development Paradigms: Towards an Integration of Engineering, Design and Management Approaches-Proceedings of the International Urban Water Conference, Heverlee, Belgium, 15–19 September 2008; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 557–565. [Google Scholar]

- Dolinska, A. Bringing farmers into the game. Strengthening farmers’ role in the innovation process through a simulation game, a case from Tunisia. Agric. Syst. 2017, 157, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, D.; Schut, M.; Klerkx, L.; van Asten, P. Compositional dynamics of multilevel innovation platforms in agricultural research for development. Sci. Public Policy 2017, 44, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, S.P.; Farrow, A.; Trienekens, J.H.; Omta, S.W.F. Stakeholder roles for fostering ambidexterity in Sub-Saharan African agricultural netchains for the emergence of multi-stakeholder cooperatives. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2016, 16, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dight, I.J.; Scherl, L.M. The International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI): Global priorities for the conservation and management of coral reefs and the need for partnerships. Coral Reefs 1997, 16, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, A.A.; Fatunbi, A.O. Approaches for Setting-up Multi-Stakeholder Platforms for Agricultural Research and Development. World Appl. Sci. J. 2012, 16, 981–988. [Google Scholar]

- Malley, Z.J.; Hart, A.; Buck, L.; Mwambene, P.L.; Katambara, Z.; Mng’Ong’O, M.; Chambi, C. Integrated agricultural landscape management: Case study on inclusive innovation processes, monitoring and evaluation in the Mbeya Region, Tanzania. Outlook Agric. 2017, 46, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téno, G.; Cadilhon, J.-J. Capturing the impacts of agricultural innovation platforms: An empirical evaluation of village crop-livestock development platforms in Burkina Faso. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2017, 29, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, M.; Ballantyne, P.G.; Le Borgne, E.; Lema, Z. Communication in Innovation Platforms. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/34161 (accessed on 7 June 2018).

- Leahy, M.; Davis, N.; Lewin, C.; Charania, A.; Nordin, H.; Orlič, D.; Butler, D.; Lopez-Fernadez, O. Smart Partnerships to Increase Equity in Education. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2016, 19, 84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kilelu, C.W.; Klerkx, L.; Leeuwis, C. Unravelling the role of innovation platforms in supporting co-evolution of innovation: Contributions and tensions in a smallholder dairy development programme. Agric. Syst. 2013, 118, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.; Tucker, J.; Homann-Kee Tui, S. Power Dynamics and Representation in Innovation Platforms. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/34166 (accessed on 7 June 2018).

- Sanyang, S.; Jean-Baptiste Taonda, S.; Kuiseu, J.; Coulibaly, T.; Konaté, L. A paradigm shift in African agricultural research for development: The role of innovation platforms. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2016, 14, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, P.; Oliver, D. Building Trust in Multi-stakeholder Partnerships: Critical Emotional Incidents and Practices of Engagement. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 1835–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefasi, N.; Siziba, S.; Mango, N.; Mapfumo, P.; Adekunhle, A.; Fatunbi, O. Creating food self reliance among the smallholder farmers of eastern Zimbabwe: Exploring the role of integrated agricultural research for development. Food Secur. 2012, 4, 647–656. [Google Scholar]

- Klerkx, L.; Adjei-Nsiah, S.; Adu-Acheampong, R.; Saïdou, A.; Zannou, E.; Soumano, L.; Sakyi-Dawson, O.; van Paassen, A.; Nederlof, S. Looking at agricultural innovation platforms through an innovation champion lens: An analysis of three cases in West Africa. Outlook Agric. 2013, 42, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobratee, N.; Bodhanya, S. How can we envision smallholder positioning in African agribusiness? Harnessing innovation and capabilities. J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2017, 12, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cadilhon, J.J.; Birachi, E.A.; Klerkx, L.; Schut, M. Innovation Platforms to Shape National Policy. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/34156 (accessed on 7 June 2018).

- Mulema, A.A.; Snyder, K.A.; Ravichandran, T.; Becon, M. Addressing Gender Dynamics in Innovation Platforms. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/67920 (accessed on 7 June 2018).

- Anttiroiko, A.-V. City-as-a-Platform: The Rise of Participatory Innovation Platforms in Finnish Cities. Sustain. 2016, 8, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, M.; Le Borgne, E.; Birachi, E.A.; Cullen, B.; Boogaard, B.K.; Adekunle, A.A.; Victor, M. Monitoring Innovation Platforms. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/34159 (accessed on 7 June 2018).

- Boogaard, B.K.; Dror, I.; Adekunle, A.A.; Le Borgne, E.; Rooyen, A.F.V.; Lundy, M. Developing Innovation Capacity through Innovation Platforms. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/34162 (accessed on 7 June 2018).

- Daneri, D.R.; Trencher, G.; Petersen, J. Students as change agents in a town-wide sustainability transformation: The Oberlin Project at Oberlin College. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema, Z.; Schut, M. Research and Innovation Platforms. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/34158/Brief3.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- Addy, N.A.; Poirier, A.; Blouin, C.; Drager, N.; Dubé, L. Whole-of-society approach for public health policymaking: A case study of polycentric governance from Quebec, Canada. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2014, 1331, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritter, J.Q.; McCallum, A. The snakes and ladders of user involvement: Moving beyond Arnstein. Health Policy 2006, 76, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, R.; Vera-Muñoz, C.; Belli, A. People olympics for social innovation: Co-creating the silver sharing economy for the aging society. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Valbonne, France, 17–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Western Cape Government, Homelessness. 2019. Available online: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/general-publication/homelessness-0 (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Booth, B.M.; Sullivan, G.; Koegel, P.; Burnam, A. Vulnerability Factors for Homelessness Associated with Substance Dependence in a Community Sample of Homeless Adults. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2002, 28, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankivsky, O.; Vorobyova, A.; Salnykova, A.; Rouhani, S. The Importance of Community Consultations for Generating Evidence for Health Reform in Ukraine. Int. J. Heal. Policy Manag. 2016, 6, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hickey, S.; Mohan, G. (Eds.) Participation: From Tyranny to Transformation? Exploring New Approaches to Participation in Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, N.; Wright, S. Power and Participatory Development: Theory and Practice; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Penderis, S. Theorizing participation: From tyranny to emancipation. J. African Asian Local Gov. Stud. 2012, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Effective Evaluation: Improving the Usefulness of Evaluation Results through Responsive and Naturalistic Approaches; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. ECTJ 1981, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruyt, K.; Gozal, D. Development of pediatric sleep questionnaires as diagnostic or epidemiological tools: A brief review of Dos and Don’ts. Sleep Med. Rev. 2011, 15, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHorney, C.A.; Bricker, D.E.; Robbins, J.; Kramer, A.E.; Rosenbek, J.C.; Chignell, K.A. Chignell, The SWAL-QOL Outcomes Tool for Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults: II. Item Reduction and Preliminary Scaling. Dysphagia 2000, 15, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PoE Theme | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Action | The culmination of various planning activities in functional activities of practical value. Action gives the IP something to show for its efforts. | [13,14,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67] |

| Alignment | Developing needs-driven platform’s objectives which are rooted in the interests and needs of the platform’s participants, coordination of the activities, expectations, interests and knowledge of the platform’s participants towards realising the platform’s objectives. | [13,14,16,34,35,36,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] |

| Championing | The role taken up by platform’s stakeholders to perform the critical platform’s activities with outstanding vigour. Champions are motivated by their eagerness to see the platform operate successfully and to see the platform’s objectives realised. | [34,35,36,58,59,61,63,66,70,71,79,80] |

| Communication | The articulation of information. Communication is critical to establish and maintain stakeholder relationships. Communication is the power source to any partnership [72]. Includes both formal and informal channels of communication. A broad range of communication practices using different types of media is included. | [13,16,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,71,72,73,74,76,79] |

| Conflict management | The mitigation of potential misunderstandings and issues which may lead to conflicts between stakeholders. Conflicts are addressed immediately. The objectives of conflict management include maintaining collaboration and alignment amongst stakeholders. | [13,16,58,60,61,62,65,68] |

| Facilitation | The process of maintaining a healthy platform through mediation. Facilitation oversees the implementation of the other PoE concepts. Facilitation is often an assigned role in the platform. | [13,16,34,36,59,61,62,66,67,68,69,70,72,74,75,76,79,81,82] |

| Gender dynamics | Deals with ensuring that inclusivity among gender roles is achieved. The interests of women are represented, and women have a voice in the platform. Requires an understanding of cultural norms. | [82] |

| Managing power dynamics | The equity among platform’s stakeholders is maintained by managing power dynamics. This serves to counter the effects of self-interest and competitiveness among stakeholders. Weaker platform’s participants are empowered. | [13,16,35,58,61,62,63,64,65,66,72,75,81,83] |

| Monitoring evaluation and feedback | The processes and techniques coupled to the continuous tracking of platform’s activities, the appraisal of these activities and reporting the outcomes. Allows for problems to be identified and improvements to be implemented. The participants who are responsible for various platform’s activities are held accountable. | [16,34,35,36,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,72,73,74,75,76,84] |

| Participation | The engagement of stakeholders with various platform’s activities. Stakeholders contribute their knowledge and skillsets towards realising the platform’s objectives through participation. Participation is required for real inclusion to be realised [52]. | [13,34,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,68,70,75,83] |

| Resources and capacity | Considers the physical, financial and human resources which are critical to a platform’s functioning. Additionally, considers the existing capacities of the platform’s stakeholders and how these capacities are to be leveraged and further developed towards increasing the platform’s own capacity. | [13,14,15,16,34,35,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,71,72,73,80,85,86] |

| Shared learning | Refers to the effects of the continuous flow of information within and across platform’s boundaries. Includes the sharing of knowledge between platform’s stakeholders. The partnership approach of the platform encourages the sharing of new ideas and the development of improved solutions. The consequence of shared learning is the increase in the capacity of stakeholders. | [13,35,58,59,60,63,64,65,66,70,71,80,81,86,87] |

| Strategic representation | Linking diverse stakeholders to form the platform. Careful consideration is given to which stakeholder groups should be represented in the platform. Strategic representation empowers I4ID. Desirable stakeholders should be strategically identified using stakeholder analysis techniques. | [34,35,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,80,83,86] |

| Transparency | The free flow of information across platform’s borders. Transparency includes honest and accurate reporting on the implementation of platform’s activities and the consequences thereof. Transparency also relates to the interactions of platform’s stakeholders. Nothing that is of relevance to the platform and its stakeholders is withheld. | [35,36,60,61,62,63,64,66,70,72,73] |

| Trust building | Efforts made to develop and maintain relationships of trust among platform’s stakeholders, as well as to develop and maintain a feeling of trust in the platform and its intentions. Trust influences a person’s willingness to be honest and cooperate. In a partnership approach, trust is both the glue that holds the partnership together and the lubricant that allows it to operate effectively [60,67,76,77]. | [13,35,36,58,60,61,62,63,64,66,67,68,69,71,73,76,77,78,88] |

| Visioning and planning | The development of a “roadmap” [63,64] of what the platform is looking to achieve and how. Visioning is followed by the planning of executable activities towards realising the vision. If visioning and planning are not followed by action, the platform has little to show for its efforts. | [13,61,62,63,64,66,83] |

| Category | Item |

|---|---|

| Implementation | Intended beneficiaries and/or users are sufficiently aware of intervention activities |

| Stakeholders clearly understand the purpose and benefits of intervention activities | |

| Stakeholders clearly understand how intervention activities work | |

| Alignment | Stakeholder visions and directions coexist cooperatively |

| Championing | Champions provide an entry point to local communities |

| Conflict management | Stakeholders make their expectations known |

| Stakeholders can communicate their concerns, e.g., the presence of a facilitator | |

| Acknowledge that conflict will happen and must be managed | |

| Facilitation | A facilitator is accessible to stakeholders |

| A facilitator is culturally relevant to the context of the challenge landscape | |

| Gender and racial dynamics | Awareness of dynamics existing between stakeholders of different races |

| Stakeholders’ cultural norms are understood and respected | |

| Managing power dynamics | Stakeholders value the expertise of other stakeholders |

| Shared information is not obscured to the benefit of specific stakeholders | |

| Conflicts of interest are identified and managed | |

| Pre-empt and mitigate effects of factors which increase participant vulnerabilities | |

| Mechanisms of resistance are recognised and managed | |

| Participation | Approaches to encourage involvement in interventions are in place, e.g., incentives for participation |

| Stakeholders (including the beneficiaries) take ownership of the initiatives | |

| Participatory approach is people-centric to empower participants | |

| Improved understanding of lifestyle challenges experienced by the commonly marginalised communities | |

| Stakeholders govern the dissemination of information to external parties | |

| Resources and capacity | Help stakeholders identify what challenges are present in their context |

| Existing knowledge and resources are acknowledged and used | |

| Strategic representation | Potential champions are identified and are the first to be engaged |

| Existing stakeholder networks are leveraged in stakeholder identification | |

| Transparency | Stakeholders are fully informed with accurate information |

| Trust building | Visible signs of interest in the activities of stakeholders even outside of the context of the IP |

| Engage stakeholders in a sincere and respectful manner | |

| Credibility is necessary when engaging participants | |

| Vision and direction are important when engaging stakeholders | |

| Visioning and planning | Challenges present in the contexts for interventions are understood |

| Long-term goals are established and recognisable | |

| Vision coexists with and supports stakeholders’ visions | |

| Rolldown of participation | Keep stakeholders informed about progress and achievements of initiatives |

| Acknowledge stakeholders for their contributions once their participation has concluded |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Edlmann, F.R.P.; Grobbelaar, S. A Framework of Engagement Practices for Stakeholders Collaborating around Complex Social Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910828

Edlmann FRP, Grobbelaar S. A Framework of Engagement Practices for Stakeholders Collaborating around Complex Social Challenges. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910828

Chicago/Turabian StyleEdlmann, Frederick Robert Peter, and Sara Grobbelaar. 2021. "A Framework of Engagement Practices for Stakeholders Collaborating around Complex Social Challenges" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910828

APA StyleEdlmann, F. R. P., & Grobbelaar, S. (2021). A Framework of Engagement Practices for Stakeholders Collaborating around Complex Social Challenges. Sustainability, 13(19), 10828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910828