Dialogues in Sustainable HRM: Examining and Positioning Intended and Continuous Dialogue in Sustainable HRM Using a Complexity Thinking Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sustainable HRM

2.1. HRM and Sustainability

2.2. The Paradoxical Nature of Sustainable HRM

2.3. The Ideological Nature of Sustainable HRM

3. Dialogue Literature

3.1. Defining Dialogue

3.2. Two Dominant Views: Intentional and Continuous Dialogue

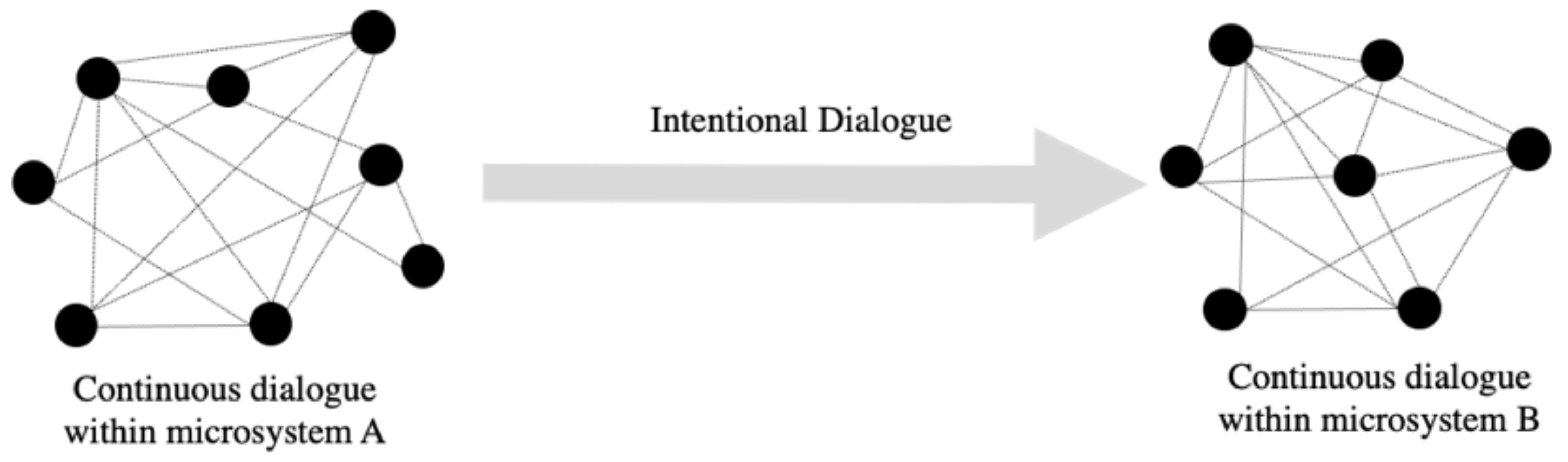

4. Dialogue and Complexity Thinking

4.1. Understanding Intentional and Continuous Dialogue Using Complex Adaptive Systems

4.1.1. Self-Organization, Emergence, and Nonlinearity

4.1.2. Attractors

4.1.3. Power Distribution

4.1.4. Values and Norms

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.1.1. Dialogue in the Context of Sustainable HRM

5.1.2. The Role of Power Distributions in Dialogue

5.1.3. Emerging Outcomes of Dialogue

5.2. Implications for Future Research

5.3. Implications for Practice

5.3.1. Pattern Sensitivity

5.3.2. Narrative and Linguistic Sensitivity

5.3.3. Temporality

5.3.4. Reflexivity

5.4. Avenues for Future Research

5.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford Paperbacks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; ISBN 978-0-19-282080-8. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Triple Bottom-Line Reporting: Looking for Balance. Aust. CPA 1999, 69, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3. United Nations General Assembly. In United Nations Resolution 70/1: Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Janssens, M.; Steyaert, C. HRM and Performance: A Plea for Reflexivity in HRM Studies. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Akkermans, J. Sustainable Careers: Towards a Conceptual Model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Wes, H.; Zink, K.J. Sustainability and HRM. In Sustainability and Human Resource Management; CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Ehnert, I., Harry, W., Zink, K.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 3–32. ISBN 978-3-642-37523-1. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Freitas, W.R.; Jabbour, C.C.J.; Santos, F.C.A. Continuing the Evolution: Towards Sustainable HRM and Sustainable Organizations. Bus. Strategy Ser. 2011, 12, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond Strategic Human Resource Management: Is Sustainable Human Resource Management the next Approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, A.; Brandl, J.; Aust, I. Handling Tensions in Human Resource Management: Insights from Paradox Theory. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 33, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, T.S.-C.; Law, K.K. Sustainable HRM: An Extension of the Paradox Perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 100818, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bücker, J.; Peters, P.; El Aghdas, N. Managing the future workforce in a sustainable way: Exploring paradoxical tensions associated with flexible work. In Human Resource Management at the Crossroads: Challenges and Future Directions; Lopez-Cabrales, A., Valle-Cabrera, R., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2019; pp. 160–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I. Paradox as a lens for theorizing sustainable HRM. In Sustainability and Human Resource Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Parkin Hughes, C. A Paradox Perspective on Sustainable Human Resource Management. In Sustainable Human Resource Management: Strategies, Practices and Challenges; Management, Work & Organizations; Mariappanadar, S., Ed.; Red Globe: London, UK, 2019; pp. 61–77. ISBN 978-1-137-53059-2. [Google Scholar]

- Geare, A.; Edgar, F.; McAndrew, I. Employment Relationships: Ideology and HRM Practice. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 1190–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prins, P.; Van Beirendonck, L.; De Vos, A.; Segers, J. Sustainable HRM: Bridging Theory and Practice through the ’Respect Openness Continuity (ROC)’-Model. Manag. Rev. 2014, 25, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafenbrädl, S.; Waeger, D. Ideology and the Micro-Foundations of CSR: Why Executives Believe in the Business Case for CSR and How This Affects Their CSR Engagements. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 60, 1582–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhueser, W. Empirical Research on Human Resource Management as a Production of Ideology. Manag. Rev. 2011, 22, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenwood, M.; Van Buren, H.J. Ideology in HRM Scholarship: Interrogating the Ideological Performativity of ‘New Unitarism’. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 142, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buren, H.J. The Value of Including Employees: A Pluralist Perspective on Sustainable HRM. Empl. Relat. 2020. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G. Images of Organization; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Örtenblad, A.; Putnam, L.L.; Trehan, K. Beyond Morgan’s Eight Metaphors: Adding to and Developing Organization Theory. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kira, M.; Lifvergren, S. Sowing seeds for sustainability in work systems. In Sustainability and Human Resource Management; CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Ehnert, I., Harry, W., Zink, K.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-37523-1. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Grosser, T.J.; Roebuck, A.A.; Mathieu, J.E. Understanding Work Teams From a Network Perspective: A Review and Future Research Directions. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 1002–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, H.; Keegan, A. The Ethics of Engagement in an Age of Austerity: A Paradox Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 162, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammond, S.C.; Sanders, M.L. Dialogue as Social Self-Organization: An Introduction. Emergence 2002, 4, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K. Organizational visions of sustainability. In Creating Sustainable Work Systems: Developing Social Sustainability; Docherty, P., Kira, M., Shani, A.R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- De Prins, P. ’Beyond the Clash?’: Union—Management Partnership through Social Dialogue on Sustainable HRM. Lessons from Belgium. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 1–21, OnlineFirst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Savanevičienė, A. Designing Sustainable HRM: The Core Characteristics of Emerging Field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ackers, P. Neo-pluralism as a research approach in contemporary employment relations and HRM: Complexity and dialogue. In Elgar Introduction to Theories of Human Resources and Employment Relations; Townsend, K., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- Aust, I.; Brandl, J.; Keegan, A. State-of-the-Art and Future Directions for HRM from a Paradox Perspective: Introduction to the Special Issue. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, H.; Ramdhony, A.; Reddington, M.; Staines, H. Opening Spaces for Conversational Practice: A Conduit for Effective Engagement Strategies and Productive Working Arrangements. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2713–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, S.C.; Anderson, R.; Cissna, K.N. Chapter 5: The Problematics of Dialogue and Power. In Communication Yearbook; Kalbfleish, P.J., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 2003; Volume 27, pp. 125–157. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.; Zediker, K. Dialogue as Tensional, Ethical Practice. South. Commun. J. 2000, 65, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomme, R.J. Leadership, Complex Adaptive Systems, and Equivocality: The Role of Managers in Emergent Change. Organ. Manag. J. 2012, 9, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, R.G.L.; Bright, J.E.H. Applying Chaos Theory to Careers: Attraction and Attractors. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherblom, S.A. Complexity-Thinking and Social Science: Self-Organization Involving Human Consciousness. New Ideas Psychol. 2017, 47, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, R. Tool and Techniques of Leadership and Management: Meeting the Challenge of Complexity; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, J.W.; Ramstad, P.M. Talentship, Talent Segmentation, and Sustainability: A New HR Decision Science Paradigm for a New Strategy Definition. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.J.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Olanre, F.O. Green Human Resource Management: A Systematic Literature Review from 2007 to 2019. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 27, 2005–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management; Contributions to Management Science; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-7908-2187-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mariappanadar, S. Sustainable HRM practices: Values and characteristics. In Sustainable human resource management: Strategies, practices and challenges; Management, Work & Organizations; Mariappanadar, S., Ed.; Red Globe: London, UK, 2019; pp. 81–104. ISBN 978-1-137-53059-22. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward a Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic Equilibrium Model of Organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulrich, D.; Kryscynski, D.; Brockbank, W.; Ulrich, M. Victory through Organization: Why the War for Talent Is Failing Your Company and What You Can Do about It; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-259-83765-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.W.; Smith, W.K. Paradox as a Metatheoretical Perspective: Sharpening the Focus and Widening the Scope. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2014, 50, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calton, J.M.; Payne, S.L. Coping With Paradox: Multistakeholder Learning Dialogue as a Pluralist Sensemaking Process for Addressing Messy Problems. Bus. Soc. 2003, 42, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeau-Vallée, M.; Denis, J.-L.; Normandin, J.M.; Therrien, M.-C. Alternate Prisms for Pluralism and Paradox in Organizations. In The Oxford Handbook or Organizational Paradox; Smith, W.K., Lewis, M.W., Jarzabkowski, P., Langley, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 263–286. [Google Scholar]

- De Prins, P.; Stuer, D.; Gielens, T. Revitalizing Social Dialogue in the Workplace: The Impact of a Cooperative Industrial Relations Climate and Sustainable HR Practices on Reducing Employee Harm. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1684–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M. Organizational Symbolism and Ideology. J. Manag. Stud. 1991, 28, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, P.M.; Matthews, L.; Dóci, E.; McCarthy, L.P. An Ideological Analysis of Sustainable Careers: Identifying the Role of Fantasy and a Way Forward. Career Dev. Int. 2020. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Do HRM Systems Impose Restrictions on Employee Quality of Life? Evidence from a Sustainable HRM Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geare, A.; Edgar, F.; McAndrew, I.; Harney, B.; Cafferkey, K.; Dundon, T. Exploring the Ideological Undercurrents of HRM: Workplace Values and Beliefs in Ireland and New Zealand. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2275–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aust, I.; Matthews, B.; Muller-Camen, M. Common Good HRM: A Paradigm Shift in Sustainable HRM? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prins, P. Bridging sustainable HRM theory and practice: The Respect, Openness and Continuitive model. In Sustainable Human Resource Management: Strategies, Practices and Challenges; Management, Work & Organizations; Mariappanadar, S., Ed.; Red Globe: London, UK, 2019; pp. 188–215. ISBN 978-1-137-53059-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, H.; Kuvaas, B. Human Resource Management Systems, Employee Well-Being, and Firm Performance from the Mutual Gains and Critical Perspectives: The Well-Being Paradox. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 59, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D.; Nichol, L. (Eds.) On Dialogue; Routledge Classics; Routledge: London, UK , 2004; ISBN 978-0-415-33641-3. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, F.J.; Powley, E.H.; Pearce, B. Hermeneutic philosophy and organizational theory. In Philosophy and Organization Theory; Research in the Sociology of Organizations; Tsoukas, H., Chia, R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; Volume 32, pp. 181–213. ISBN 978-0-85724-596-0. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs, W. Dialogue: The Art of Thinking Together; Currency Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-307-48378-2. [Google Scholar]

- Reitz, M. Dialogue in Organizations: Developing Relational Leadership; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-137-48912-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, R.; Barker, S.; Boydell, K.; Buus, N.; Rhodes, P.; River, J. Dialogical Inquiry: Multivocality and the Interpretation of Text. Qual. Res. 2020, 21, 1468794120934409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M.J.; Ehrlich, S. 5. The dialogic organization. In The Transformative Power of Dialogue; Research in Public Policy Analysis and Management; Roberts, N.C., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2002; Volume 12, pp. 107–131. ISBN 978-1-84950-165-1. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.; Baxter, L.A.; Cissna, K.N. Concluding voices, conversation fragments, and a temporary synthesis. In Dialogue: Theorizing Difference in Communication Studies; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Deetz, S.; Simpson, J. Critical organizational dialogue. In Dialogue: Theorizing Difference in Communication Studies; Anderson, R., Baxter, L.A., Cissna, K.N., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dafermos, M. Relating Dialogue and Dialectics: A Philosophical Perspective. Dialogic Pedagog. 2018, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Womack, P. Dialogue; The New Critical Idiom; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-415-32921-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays; University of Texas Press Slavic Series; 18th Paperback Printing; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-292-71534-9. [Google Scholar]

- Buber, M. I and Thou/artin Buber; Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1970; ISBN 978-0-684-71725-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, H.J.M.; Gieser, T. (Eds.) Handbook of Dialogical Self Theory; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume XIV, p. 503. ISBN 978-1-107-00651-5. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, S.R.; e Cunha, M.P. Organizational Dialectics; Smith, W.K., Lewis, M.W., Jarzabkowski, P., Langley, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Industrial Relations & Conflict Management. Shaping Inclusive Workplaces through Social Dialogue, 1st ed.; Arenas, A., Di Marco, D., Euwema, M.C., Munduate, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-66393-7. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, R.; Mowles, C. Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics. The Challenge of Complexity Tot Ways of Thinking about Organisations, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grill, C.; Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Wikström, E.; Lindgren, E.-C. Multiple Balances in Workplace Dialogue: Experiences of an Intervention in Health Care. J. Workplace Learn. 2015, 27, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, B.; Bineham, J.L. From Debate to Dialogue: Toward a Pedagogy of Nonpolarized Public Discourse. South Commun. J. 2000, 65, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stacey, R. Complexity and Group Processes: A Radically Social Understanding of Individuals; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J.; Hazy, J.K.; Lichtenstein, B.B. Complexity and the Nexus of Leadership: Leveraging Nonlinear Science to Create Ecologies of Innovation, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-230-62227-2. [Google Scholar]

- Marion, R. The Edge of Organization: Chaos and Complexity Theories of Formal Social Systems; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-7619-1265-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M. Complexity: A Guided Tour; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-19-512441-5. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.; McShea, D.W. Individual versus Social Complexity, with Particular Reference to Ant Colonies. Biol. Rev. 2001, 76, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chia, R. From Complexity Science to Complex Thinking: Organization as Simple Location. Organization 1998, 5, 341–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letiche, H.; Lissack, M.; Schultz, R. Coherence in the Midst of Complexity: Advances in Social Complexity Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Colbert, B.A.; Kurucz, E.C. A Complexity Perspective on Strategic Human Resource Management. In The SAGE Handbook of Complexity and Management; Allen, P., Maguire, S., McKelvey, B., Eds.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4462-0974-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan, P.J.; Xu, Y. Fostering Corporate Sustainability. In Sustainability and Human Resource Management; CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Ehnert, I., Harry, W., Zink, K.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 225–245. ISBN 978-3-642-37523-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers, B.S.; Stoker, J.I. Development and Performance of Self-Managing Work Teams: A Theoretical and Empirical Examination. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloux, F. Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage in Human Consciousness; Nederlandse Editie; Uitgeverij Lannoo: Tiel, Belgium; Het Eerste Huis: Haarzuilens, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Magpili, N.C.; Pazos, P. Self-Managing Team Performance: A Systematic Review of Multilevel Input Factors. Small Group Res. 2017, 49, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wax, A.; DeChurch, L.A.; Contractor, N.S. Self-Organizing Into Winning Teams: Understanding the Mechanisms That Drive Successful Collaborations. Small Group Res. 2017, 48, 665–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerheim, W.; Van Rossum, L.; Ten Have, W.D. Successful Implementation of Self-Managing Teams. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2019, 32, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wheatley, M.J. Leadership and the New Science: Learning about Organization from an Orderly Universe, 1st ed.; Berrett-Koehler Publ.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-1-881052-44-9. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall, P.; Purcell, J. Strategic Human Resource Management: Where Have We Come from and Where Should We Be Going? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2000, 2, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F. Theories of Power and Social Change. Power Contestations and Their Implications for Research on Social Change and Innovation. J. Polit. Power 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, B.H. A Power/Interaction Model of Interpersonal Influence: French and Raven Thirty Years Later. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1992, 7, 217–244. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, N.; Scotson, J.L. The Established and the Outsiders; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Leirvik, B. Dialogue and Power: The Use of Dialogue for Participatory Change. AI Soc. 2005, 19, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuis, J.W.; Peters, P. A Social Complexity perspective. In Human Centered Organizational Culture: Global Dimensions; Human Centered Management; Lepeley, M.-T., Morales, O., Essens, P., Beutell, N., Majluf, N., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-00-309202-5. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, K.A.; Cilliers, P.; Lissack, M. Complexity Science: A ‘Grey’ Science for the ‘Stuff in Between. Emergence 2001, 3, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbord, M.R.; Janoff, S. Future Search: Getting the Whole System in the Room for Vision, Commitment, and Action, Updated and Expanded, 3rd ed.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-60509-428-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yanow, D.; Ybema, S. Interpretivism in organizational research: On elephants and blind researchers. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D.A., Bryman, A., Eds.; SAGE Publication Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 39–60. ISBN 978-1-4129-3118-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn, A.; Potter, J. Discourse analytic practice. In Qualitative Research Practice; SAGE Publication Inc.: Thousans Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; Volume 168. [Google Scholar]

- Audet, R. The Double Hermeneutic of Sustainability Transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2014, 11, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, C.E. The Science of “Muddling Through". Public Adm. Rev. 1959, 19, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, S. Managerial Narratives: A Critical Dialogical Approach to Managerial Identity. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2010, 5, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wortham, S. Narratives in Action: A Strategy for Research and Analysis; Counseling and Development Series; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-8077-4076-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kärreman, D.; Spicer, A.; Hartmann, R.K. Slow Management. Scand. J. Manag. 2021, 37, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, N. Involvement and Detachment; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1987; ISBN 978-0-631-12682-9. [Google Scholar]

| Distinction | Description |

|---|---|

| Conversational practice | Dialogue can be discerned clearly from other conversational practices like debate and dialectics. |

| Praxis–poiesis | Dialogue can be regarded as praxis (intuitive, practical wisdom), or as poiesis (procedural, technical). |

| Generic–local | Dialogue can be seen on a generic, institutional level or dialogue on a local level within microsystems. |

| Dialogue1–Dialogue2 | Dialogue is a teachable, structured procedure, or dialogue is an elusive, communing process. |

| Noun–verb | Dialogue can be seen as a noun (normative, episodic) or as a verb (processual, non-episodic). |

| Intentional Perspective on Dialogue | Continuous Perspective on Dialogue |

|---|---|

| Dialogue as a ‘noun’ | Dialogue as a ‘verb’ |

| Dialogue as an explicit, episodic activity | Dialogue as an implicit, continuous process |

| Dialogue as poiesis (making) | Dialogue as praxis (doing) |

| Dialogue is content-driven, monovocal (predefined topics) | Dialogue is process-driven, plurivocal (undefined outcomes) |

| Dialogue is procedure-focused and learnable (Dialogue1) | Dialogue is process-focused and elusive (Dialogue2) |

| Intentional (someone defines the intention of the dialogical endeavour) | Emergent (dialogue has emergent outcomes that can result in intentions) |

| Liberal humanistic conceptual positioning: one should do dialogue | Critical hermeneutic/postmodern positioning: dialogue happens |

| Prescriptive perspective on dialogue | Descriptive perspective on dialogue |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nuis, J.W.; Peters, P.; Blomme, R.; Kievit, H. Dialogues in Sustainable HRM: Examining and Positioning Intended and Continuous Dialogue in Sustainable HRM Using a Complexity Thinking Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910853

Nuis JW, Peters P, Blomme R, Kievit H. Dialogues in Sustainable HRM: Examining and Positioning Intended and Continuous Dialogue in Sustainable HRM Using a Complexity Thinking Approach. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910853

Chicago/Turabian StyleNuis, Jan Willem, Pascale Peters, Rob Blomme, and Henk Kievit. 2021. "Dialogues in Sustainable HRM: Examining and Positioning Intended and Continuous Dialogue in Sustainable HRM Using a Complexity Thinking Approach" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910853

APA StyleNuis, J. W., Peters, P., Blomme, R., & Kievit, H. (2021). Dialogues in Sustainable HRM: Examining and Positioning Intended and Continuous Dialogue in Sustainable HRM Using a Complexity Thinking Approach. Sustainability, 13(19), 10853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910853