Does Environmental Information Disclosure Affect the Sustainable Development of Enterprises: The Role of Green Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. EID and Corporate GI

2.2. Government Level: Energy-Saving Innovation Subsidy Effect

2.3. Social Level: Media Attention Effect

2.4. Enterprise Level: Cost Effect of Debt Financing

3. Research Design

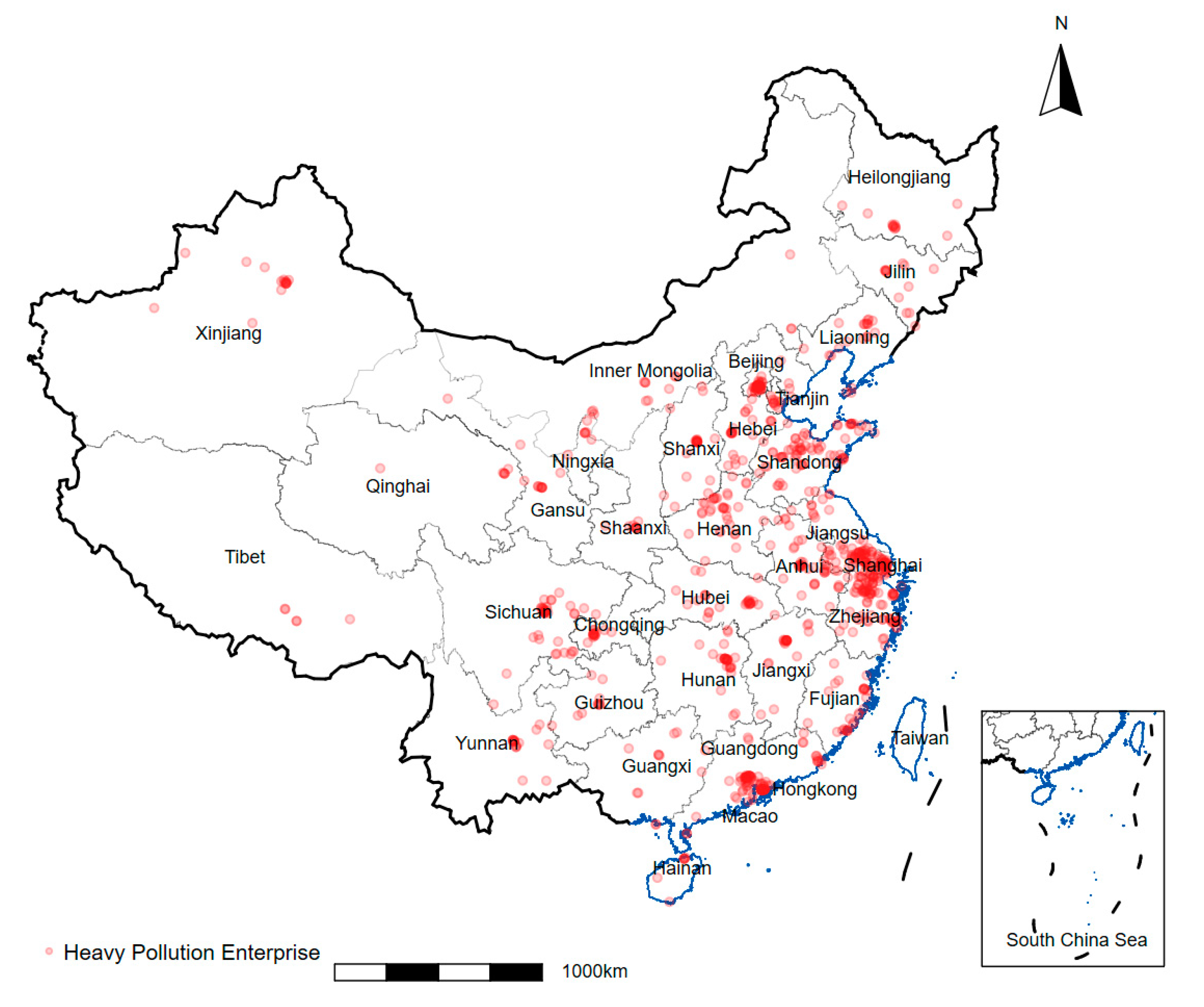

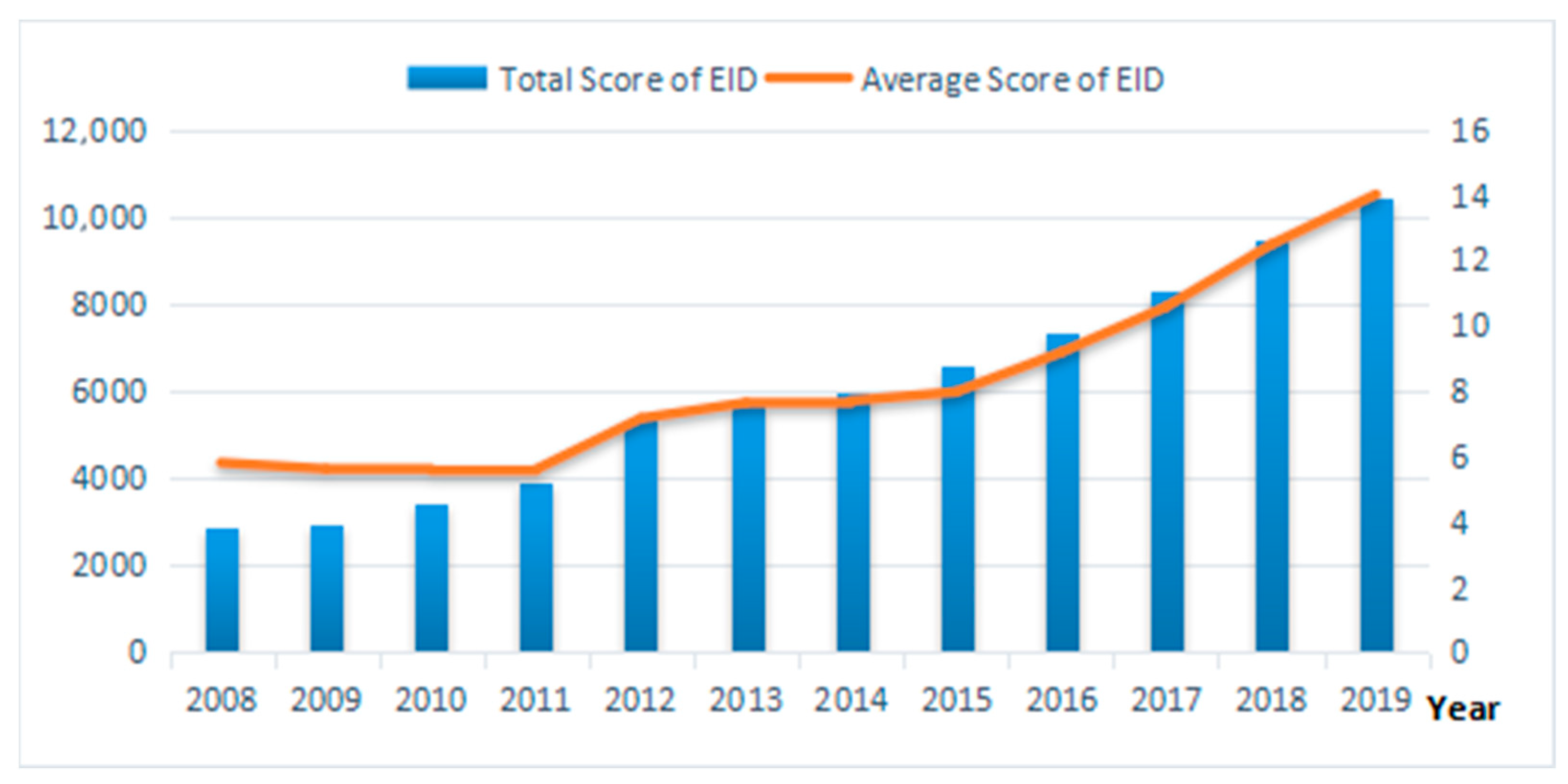

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Design

3.3. Model Setting

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Preliminary Regression Results

4.2. Mechanism Analysis

4.3. Robustness Tests

5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1. Patent Category Heterogeneity

5.2. Enterprise Heterogeneity

5.3. City Heterogeneity

6. Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

- 1)

- As a kind of voluntary environmental regulation, the effectiveness of EID on innovation is obviously insufficient. Previous studies mostly focused on the impact of command-and-control and market-incentive environmental regulation policies on innovation, including the work of some scholars in the study of the European carbon emissions trading system policy, and found that market-based instruments have no effect on GI [37], but the alternative view is that market-based tools have a more significant incentive effect on GI than command-and-control types [36]. Additionally, based on the negative binomial model and the least square model used to carry out the empirical analysis, we found that the type of EID, as a voluntary environmental regulation, significantly promoted the absolute and relative GI levels of enterprises, and when replacing the control, dependent, and independent variables, adding a city level for EID, and dividing EID into different growth types, the result was still robust.

- 2)

- After verifying that corporate EID has a positive role in promoting GI, this study used the intermediary model to conduct intermediary tests from three channels: government-level energy-saving innovation subsidies, social-level media attention, and corporate-level debt financing costs. The results found that the internal mechanism of corporate EID to promote GI mainly comes from the government-level energy-saving innovation subsidy effect and the social-level media attention effect, while failure of the corporate-level debt financing cost channel test may be due to the reduction in debt financing costs being not enough to affect the GI R&D activities that require long-term substantial funding support.

- 3)

- From the perspective of the heterogeneity of two types of patents, EID promotes GI activities in enterprises regarding alternative energy production, energy conservation, and waste management, and it had the most obvious role in promoting energy conservation innovation. Moreover, compared with green patents for utility models, corporate EID had a greater role in promoting GI activities for invention patents. From the perspective of the heterogeneity of ownership by enterprises, state-owned enterprise EID was more conducive to GI activities than private enterprises. This may be because, in order to obtain more national resources, state-owned enterprises have lower operating efficiencies and market vitalities than private enterprises [87]. Support for state-owned enterprises will cause these enterprises to respond more actively to government policies and to disclose more environmental information. In terms of the heterogeneity of administrative levels in different cities, the positive effects of corporate EID in cities with high administrative levels on GI were not significant, while corporate EID in cities with low administrative levels significantly promoted GI.

6.2. Implications

- 1)

- In view of the current situation of insufficient innovation drivers and environmental pollution in China, governments at all levels should spare no effort to implement innovation-driven development strategies. An effective innovative environmental policies at this stage through environmental information policies can encourage heavily polluting companies to implement GI development strategies, to unify economic and environmental benefits, and to provide an important guarantee for sustained and healthy development of a regional economy. Therefore, the government should adhere to the practice of combining market and administrative means, effectively implement EID policy, and introduce corresponding measures in combination with regions and enterprises, based on actual results. Companies should uphold the concept of sustainable development and green governance and should strengthen the reasonable construction of an internal EID system for companies.

- 2)

- As two important channels for EID to promote corporate GI, actively leveraging the power of government subsidies and social public opinion supervision is necessary. For enterprises that actively undertake social responsibilities and disclose high-quality environmental information, the government must commend, publicize, and provide material rewards. At the same time, in the process of supporting the GI of enterprises, a reasonable evaluation mechanism should be established to achieve transparent procedures and to prevent some enterprises from taking subsidy resources through rent-seeking activities. Public media should supervise the environmental performance and disclosure level of enterprises in real time and resolutely expose their environmental pollution and false information disclosure.

- 3)

- A differentiated EID supervision system should be developed. Blindly strengthening environmental regulations overall means not only high costs for government regulatory agencies but also lower regulatory efficiency. Therefore, in EID supervision, differentiated measures should be implemented for different types of enterprises. In order to accelerate the green transformation of enterprises, the EID system should focus on improving the quality of EID in areas with poor information disclosure to strengthen the supervision of information disclosure in this area, and on that basis strengthening the EID level of private enterprises and alleviating the overloaded state of functions in cities with high administrative levels. Sustainable economic development should also be achieved.

6.3. Research Gaps and Direction of Further Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mi, Z.; Zheng, J.; Meng, J.; Zheng, H.; Li, X.; Coffman, D.; Woltjer, J.; Wang, S.; Guan, D. Carbon emissions of cities from a consumption-based perspective. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qu, S.; Wang, H.; Liang, S.; Shapiro, A.M.; Suh, S.; Sheldon, S.; Zik, O.; Fang, H.; Xu, M. A Quasi-Input-Output model to improve the estimation of emission factors for purchased electricity from interconnected grids. Appl. Energy 2017, 200, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, C.; Xie, R. Structural, Innovation and Efficiency Effects of Environmental Regulation: Evidence from China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Pilot. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 75, 741–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wei, W. Has environmental information disclosure eased the economic inhibition of air pollution? J. Clean. Prod. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.F.; Gilpatric, S.M.; Liu, L. Regulation with direct benefits of information disclosure and imperfect monitoring. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2009, 57, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, S.X.; Xu, X.D.; Yin, H.T.; Tam, C.M. Factors that Drive Chinese Listed Companies in Voluntary Disclosure of Environmental Information. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.C.; Campbell, D.; Shrives, P.J. Content analysis in environmental reporting research: Enrichment and rehearsal of the method in a British–German context. Br. Account. Rev. 2010, 42, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A. Is sustainability reporting (ESG) associated with performance? Evidence from the European banking sector. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2019, 30, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Parker, L.D. Corporate Social Reporting: A Rebuttal of Legitimacy Theory. Account. Bus. Res. 1989, 19, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosajan, V.; Chang, M.; Xiong, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, S. The design and application of a government environmental information disclosure index in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Simon Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Guidry, R.P.; Hageman, A.M.; Patten, D.M. Do actions speak louder than words? An empirical investigation of corporate environmental reputation. Account. Org. Soc. 2012, 37, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.X.; Xu, X.D.; Dong, Z.Y.; Tam, V.W.Y. Towards corporate environmental information disclosure: An empirical study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.M.D.S.; Lucena, W.G.L.; Da Silva, W.V.; Bach, T.M.; Da Veiga, C.P. Explanatory Factors of the Environmental Disclosure of Potentially Polluting Companies: Evidence From Brazil. SAGE Open 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Anbumozhi, V. Determinant factors of corporate environmental information disclosure: An empirical study of Chinese listed companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 834–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khlif, H.; Guidara, A.; Souissi, M. Corporate social and environmental disclosure and corporate performance: Evidence from South Africa and Morocco. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2015, 5, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, X.; Tian, S.; He, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X. Quantifying the dynamics between environmental information disclosure and firms’ financial performance using functional data analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yao, C.; Li, Y. The impact of the amount of environmental information disclosure on financial performance: The moderating effect of corporate internationalization. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2893–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Du, X.; Zeng, Q. Does environmental information disclosure mitigate corporate risk? Evidence from China. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2021, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Doshi, A.R.; Dowell, G.W.S.; Toffel, M.W. How firms respond to mandatory information disclosure. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1209–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Yu, Q.; Fujitsuka, T.; Liu, B.; Bi, J.; Shishime, T. Functional mechanisms of mandatory corporate environmental disclosure: An empirical study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoshita, M.; Sakagami, M.; Kudoh, Y.; Tahara, K.; Inaba, A. Potential impacts of information disclosure designed to motivate Japanese consumers to reduce carbon dioxide emissions on choice of shopping method for daily foods and drinks. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 101, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, H. The impact of government environmental information disclosure on enterprise location choices: Heterogeneity and threshold effect test. J. Clean. Prod. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cailou, J.; Fuyu, Z.; Chong, W. Environmental information disclosure, political connections and innovation in high-polluting enterprises. Sci. Total Environ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, A.J.; McConnell, V.D. The impact of environmental regulations on industry productivity: Direct and indirect effects. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1990, 18, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.B.; Shadbegian, R.J. Plant vintage, technology, and environmental regulation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2003, 46, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. Directed Technical Change. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2002, 4, 781–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kihombo, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Chen, S.; Adebayo, T.S.; Kirikkaleli, D. Linking financial development, economic growth, and ecological footprint: What is the role of technological innovation? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umar, M.; Ji, X.; Kirikkaleli, D.; Shahbaz, M.; Zhou, X. Environmental cost of natural resources utilization and economic growth: Can China shift some burden through globalization for sustainable development? Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1678–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Kirikkaleli, D. Impact of renewable energy consumption, globalization, and technological innovation on environmental degradation in Japan: Application of wavelet tools. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, E.; Wield, D. Implementing New Technologies: Innovation and the Management of Technology; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, E.; Wield, D. Regulation as a means for the social control of technology. Technol. Anal. Strateg. 1994, 6, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H. Green innovation Strategy and Green innovation: The Roles of Green Creativity and Green Organizational Identity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShazo, J.R.; Sheldon, T.L.; Carson, R.T. Designing policy incentives for cleaner technologies: Lessons from California’s plug-in electric vehicle rebate program. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 84, 18–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calel, R.; Dechezleprêtre, A. Environmental Policy and Directed Technological Change: Evidence from the European Carbon Market. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2014, 98, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Xie, M. Can direct environmental regulation promote green technology innovation in heavily polluting industries? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Huang, J. Environmental regulation and real earnings management—Evidence from the SO2 emissions trading system in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, K.; Chen, H. Environmental regulation and corporate tax avoidance: A quasi-natural experiment based on the eleventh Five-Year Plan in China. Energy Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.; Schlick, C. The relationship between sustainability performance and sustainability disclosure - Reconciling voluntary disclosure theory and legitimacy theory. J. Account. Public Policy 2016, 35, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Endres, A.; Friehe, T.; Rundshagen, B. Environmental liability law and R&D subsidies: Results on the screening of firms and the use of uniform policy. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2015, 17, 521–541. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, G.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Corporate governance, external control, and environmental information transparency: Evidence from emerging markets. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2019, 58, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Walker, M.; Zeng, C.C. Do Chinese state subsidies affect voluntary corporate social responsibility disclosure? J. Account. Public Policy 2017, 36, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrizio, S.; Kozluk, T.; Zipperer, V. Environmental policies and productivity growth: Evidence across industries and firms. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 81, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.; Javakhadze, D. Corporate social responsibility and capital allocation efficiency. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 43, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zuo, J.; Jiang, H.; Huang, D.; Rameezdeen, R. Characteristics of public concern on haze in China and its relationship with air quality in urban areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Chen, D. Does Environmental Information Disclosure Benefit Waste Discharge Reduction? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Freedman, M. Social Disclosure and the Individual Investor. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1994, 7, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Li, O.Z.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y.G. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder Reaction: The Environmental Awareness of Investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, R.Y.K.; Lau, L.B.Y. Antecedents of green purchases: A survey in China. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibrell, C.; Craig, J.B.; Hansen, E.N. How managerial attitudes toward the natural environment affect market orientation and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S.; Ozanne, L. The Interactive Effect of Internal and External Factors on a Proactive Environmental Strategy and its Influence on a Firm’s Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, G. Motivating Innovation. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 1823–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montmartin, B.; Herrera, M. Internal and external effects of R&D subsidies and fiscal incentives: Empirical evidence using spatial dynamic panel models. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E. Leaders and followers: Perspectives on the Nordic model and the economics of innovation. J. Public Econ. 2015, 127, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peress, J.; Fang, L. Media Coverage and the Cross-Section of Stock Returns. J. Financ. 2008, 64, 2023–2052. [Google Scholar]

- Strycharz, J.; Strauss, N.; Trilling, D. The Role of Media Coverage in Explaining Stock Market Fluctuations: Insights for Strategic Financial Communication. Int. J. Strategy Commun. 2017, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mullainathan, S.; Shleifer, A. The Market for News. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 1031–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howitt, P.; Aghion, P. A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction. Econometrica 1992, 60, 323–351. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Wei, W.; Sun, H.; Xu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X. Can mandatory environmental information disclosure achieve a win-win for a firm’s environmental and economic performance? J. Clean. Prod. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, A.; Roberts, G.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 1794–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y. Environmental Information Disclosure of Listed Company Study on the Cost of Debt Capital Empirical Data: Based on Thermal Power Industry. Can. Soc. Sci. 2014, 6, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lindman, Å.; Söderholm, P. Wind energy and green economy in Europe: Measuring policy-induced innovation using patent data. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H. The real effect of partial privatization on corporate innovation: Evidence from China’s split share structure reform. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 64, 101661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, D. Induced Innovation and Energy Prices. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popp, D. International innovation and diffusion of air pollution control technologies: The effects of NOX and SO2 regulation in the US, Japan, and Germany. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2006, 51, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katmon, N.; Mohamad, Z.Z.; Norwani, N.M.; Farooque, O.A. Comprehensive Board Diversity and Quality of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from an Emerging Market. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 447–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M. Does Firm Size Comfound the Relationship Between Corporate Social Performance and Firm Financial Performance? J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 33, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Yang, L.; Xin, F. On Evaluating China’s Innovation Subsidy Policy: Theory and Evidence. Econ. Res. J. 2015, 50, 4–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Barron, D.N.; West, E.; Hannan, M.T. A Time to Grow and a Time to Die: Growth and Mortality of Credit Unions in New York City, 1914-1990. Am. J. Sociol. 1994, 100, 381–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziedonis, R.H. Don’t Fence Me In: Fragmented Markets for Technology and the Patent Acquisition Strategies of Firms. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 804–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, L.; Pangarkar, N.; Wu, J. The interactive effect of time and host country location on Chinese MNCs’ performance: An empirical investigation. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.W.; Beamish, P.W. International Diversification and Firm Performance: The S-curve Hypothesis. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 598–609. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, J.A.; Fortin, S. Auditor choice and the cost of debt capital for newly public firms. J. Account. Econ. 2004, 37, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnis, M. The Value of Financial Statement Verification in Debt Financing: Evidence from Private, U.S. Firms. J. Account. Res. 2011, 49, 457–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.; Trivedi, P. Regression Analysis of Count Data; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, D.; Xia, Y. Do Patents Drive Economic Growth in China-An Explanation Based on Government Patent Subsidy Policy. China Ind. Econ. 2016, 1, 83–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Liu, C.; Gao, C. The impact of environmental regulation on firm exports: Evidence from environmental information disclosure policy in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 37101–37113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.H.; Zeng, S.X.; Tam, C.M. From Voluntarism to Regulation: A Study on Ownership, Economic Performance and Corporate Environmental Information Disclosure in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, M.; Rajapakse, T.; Richardson, G. The effect of environmental information disclosure and energy product type on the cost of debt: Evidence from energy firms in China. Pac.-Basin. Financ. J. 2019, 54, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R. Does Reliance on SOEs Hamper the Improvement of Resource Allocation Efficiency? Econ. Res. J. 2018, 53, 80–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators |

|---|---|

| Disclosure vehicle | Annual report |

| Social responsibility report | |

| Environmental report | |

| Environmental management | Environmental protection concept, environmental policy and environmental goals, etc. |

| Environmental protection management system | |

| Environmental Education and Training | |

| Environmental protection special action | |

| Environmental incident emergency mechanism | |

| Environmental honor or award | |

| “Three Simultaneity” System | |

| Environmental liabilities | Wastewater discharge |

| SO2 emissions | |

| CO2 emissions | |

| COD emissions | |

| Smoke and dust emissions | |

| Industrial solid waste generation | |

| Environmental supervision and agency certification | Key pollution monitoring unit |

| Pollutant discharge standards | |

| Sudden environmental accidents, illegal incidents, petition cases, etc. | |

| ISO14001 certification | |

| Environmental performance and governance | Waste gas emission reduction treatment |

| Wastewater emission reduction treatment | |

| Smoke and dust control | |

| Solid waste utilization and disposal | |

| Control of noise, light pollution, radiation, etc. | |

| Implementation of cleaner production |

| Variables | Variable Definition | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGI | Number of green patents | 8533 | 0.65 | 2.43 | 0.00 | 18.00 |

| RGI | Percentage of green patents | 8533 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.83 |

| EID | Total score of environmental information disclosure | 8533 | 8.41 | 7.24 | 1.00 | 35.00 |

| Subsidy | Logarithm of government’s subsidies for innovation and energy saving | 5727 | 12.77 | 4.06 | 0.00 | 21.42 |

| Attention | Logarithm of the number of news of the company that appeared in newspapers and online media | 8533 | 5.25 | 1.04 | 0.00 | 10.17 |

| Cost | Multiply the ratio of interest expense to total average debt by 100 | 7699 | 2.70 | 1.65 | 0.15 | 8.03 |

| Scale | Logarithm of employees | 8533 | 7.80 | 1.22 | 2.71 | 13.22 |

| Age | The number of years the company has been listed | 8533 | 10.55 | 6.55 | 0.00 | 27.00 |

| Leverage | The ratio of total liabilities to total assets | 8533 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 1.05 |

| Capital | Logarithm of fixed capital per capita | 8529 | 12.96 | 1.00 | 10.64 | 15.92 |

| Competition | The ratio of operating profit to main business income | 8531 | 0.07 | 0.18 | −0.84 | 0.57 |

| Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q | 8533 | 2.13 | 1.68 | 0.21 | 9.63 |

| FA | The ratio of local budget expenditure to budget revenue | 4798 | 1.53 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 10.09 |

| HC | The ratio of the number of students in local colleges and universities to the total population | 5719 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| FDI | The ratio of industrial output of foreign-invested enterprises to total industrial output | 5688 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.46 |

| ER | Local SO2 removal rate | 5410 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGI | RGI | |||

| EID | 0.033 *** (0.005) | 0.026 *** (0.005) | 0.001 *** (0.000) | 0.001 *** (0.000) |

| Scale | 0.449 *** (0.046) | 0.502 *** (0.050) | 0.004 * (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) |

| Age | −0.012 (0.007) | −0.054 *** (0.010) | −0.001 * (0.000) | −0.002 *** (0.000) |

| Leverage | −0.808 *** (0.241) | −0.598 ** (0.247) | −0.000 (0.010) | 0.006 (0.010) |

| Capital | 0.264 *** (0.051) | 0.224 *** (0.055) | 0.004 ** (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) |

| Competition | −0.142 (0.262) | −0.048 (0.276) | 0.007 (0.009) | 0.009 (0.009) |

| Tobin’s Q | 0.021 (0.031) | 0.016 (0.032) | 0.000 (0.001) | −0.000 (0.001) |

| Constant | −7.568 *** (0.803) | −9.001 *** (1.014) | −0.051 (0.035) | −0.030 (0.044) |

| Year FE | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| City FE | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| N | 8527 | 8527 | 8527 | 8527 |

| Log likelihood | −5449.037 | −5318.838 | ||

| Wald Chi Square | 289.384 | 563.614 | 42.176 | 109.960 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| R2 | 0.020 | 0.037 | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsidy | RGI | Attention | RGI | Cost | RGI | |

| EID | 0.055 *** (0.010) | 0.001 *** (0.000) | 0.007 *** (0.001) | 0.001 *** (0.000) | −0.007 ** (0.003) | 0.001 *** (0.000) |

| Subsidy | 0.001 ** (0.000) | |||||

| Attention | 0.001 (0.002) | |||||

| Cost | −0.000 (0.001) | |||||

| Scale | 0.837 *** (0.079) | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.256 *** (0.012) | 0.002 (0.002) | −0.065 *** (0.025) | 0.002 (0.002) |

| Age | −0.035 *** (0.013) | −0.001 ** (0.001) | 0.014 *** (0.003) | −0.002 *** (0.000) | 0.005 (0.005) | −0.002 *** (0.000) |

| Leverage | −0.043 (0.400) | 0.002 (0.014) | 0.143 *** (0.055) | 0.006 (0.010) | 1.032 *** (0.119) | 0.008 (0.011) |

| Capital | 0.293 *** (0.082) | 0.005 * (0.003) | 0.147 *** (0.012) | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.250 *** (0.026) | 0.003 (0.002) |

| Competition | −0.044 (0.398) | 0.007 (0.013) | 0.113 ** (0.047) | 0.008 (0.009) | −1.077 *** (0.106) | 0.009 (0.010) |

| Tobin’s Q | 0.023 (0.047) | 0.000 (0.002) | 0.145 *** (0.006) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.119 *** (0.014) | −0.001 (0.001) |

| Constant | 2.232 (1.500) | −0.086 (0.053) | 0.199 (0.265) | −0.029 (0.045) | −0.989* (0.506) | −0.043 (0.047) |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Boot 95% CI | [0.000,0.000] | [−0.000,0.000] | ||||

| N | 5726 | 5726 | 8527 | 8527 | 7696 | 7696 |

| R2 | 0.092 | 0.035 | 0.414 | 0.037 | 0.245 | 0.038 |

| AGI | RGI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Replace Dependent and Independent Variables | Add City Level Control Variables | Replace Dependent and Independent Variables | Add City Level Control Variables | |

| EID | 0.816 *** (0.203) | 0.029 *** (0.007) | 0.034 *** (0.010) | 0.001 *** (0.000) |

| Scale | 0.459 *** (0.057) | 0.561 *** (0.070) | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.002 (0.003) |

| Age | −0.043 *** (0.012) | −0.070 *** (0.014) | −0.002 *** (0.000) | −0.002 *** (0.001) |

| Leverage | −0.607 ** (0.276) | −0.915 ** (0.362) | 0.016 (0.010) | 0.011 (0.015) |

| Capital | 0.204 *** (0.062) | 0.330 *** (0.077) | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.005 * (0.003) |

| Competition | 0.084 (0.298) | −1.052 *** (0.385) | 0.017 * (0.009) | −0.007 (0.014) |

| Tobin’s Q | −0.042 (0.037) | −0.029 (0.046) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.002 (0.002) |

| FA | −0.146 (0.104) | −0.003 (0.004) | ||

| HC | −7.792 *** (2.574) | −0.333 *** (0.119) | ||

| FDI | −0.815 (0.899) | −0.009 (0.041) | ||

| ER | 0.316 (0.272) | −0.011 (0.014) | ||

| Constant | −7.653 *** (1.185) | −9.216 *** (1.441) | −0.017 (0.043) | −0.025 (0.059) |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 8527 | 4444 | 8527 | 4444 |

| Log likelihood | −4275.912 | −2865.900 | ||

| Wald Chi Square | 429.105 | 309.318 | 104.612 | 94.632 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| R2 | 0.032 | 0.050 | ||

| AGI | RGI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Before 2015 | After 2015 Inclusive | Before 2015 | After 2015 Inclusive | |

| EID | 0.020 ** (0.008) | 0.031 *** (0.007) | 0.001 ** (0.000) | 0.001 *** (0.000) |

| Scale | 0.621 *** (0.075) | 0.574 *** (0.071) | 0.001 (0.003) | 0.005 (0.003) |

| Age | −0.080 *** (0.015) | −0.046 *** (0.012) | −0.002 *** (0.001) | −0.001 *** (0.001) |

| Leverage | −0.823 ** (0.391) | −0.379 (0.363) | 0.022 (0.015) | 0.001 (0.017) |

| Capital | 0.346 *** (0.082) | 0.246 *** (0.081) | 0.005 (0.003) | 0.003 (0.003) |

| Competition | −0.264 (0.478) | −0.113 (0.349) | 0.007 (0.013) | 0.002 (0.014) |

| Tobin’s Q | −0.053 (0.059) | 0.037 (0.040) | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.000 (0.002) |

| Constant | −9.976 *** (1.526) | −10.418 *** (1.415) | −0.029 (0.057) | −0.064 (0.060) |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 4603 | 3924 | 4603 | 3924 |

| Log likelihood | −2547.321 | −2887.713 | ||

| Wald Chi Square | 287.229 | 300.606 | 79.194 | 75.744 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| R2 | 0.041 | 0.040 | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Energy Production | Energy Conservation | Waste Management | Invention Patents | Utility Model Patents | |

| EID | 0.019 ** (0.008) | 0.039 *** (0.010) | 0.024 *** (0.006) | 0.022 *** (0.006) | 0.020 *** (0.006) |

| Scale | 0.506 *** (0.066) | 0.667 *** (0.100) | 0.427 *** (0.055) | 0.468 *** (0.052) | 0.440 *** (0.060) |

| Age | −0.036 ** (0.016) | −0.051 *** (0.019) | −0.046 *** (0.012) | −0.039 *** (0.012) | −0.050 *** (0.013) |

| Leverage | −0.475 (0.412) | −1.707 *** (0.562) | −0.665 ** (0.302) | −0.514 * (0.289) | −1.085 *** (0.344) |

| Capital | 0.202 ** (0.085) | 0.342 *** (0.112) | 0.359 *** (0.069) | 0.224 *** (0.063) | 0.170 ** (0.073) |

| Competition | 0.751 (0.500) | −1.297 ** (0.610) | −0.174 (0.334) | 0.126 (0.318) | −0.487 (0.401) |

| Tobin’s Q | 0.054 (0.052) | −0.068 (0.085) | −0.032 (0.043) | 0.012 (0.037) | −0.052 (0.050) |

| Constant | −9.677 *** (1.458) | −12.851 *** (2.159) | −10.002 *** (1.226) | −8.823 *** (1.113) | −8.679 *** (1.383) |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 8527 | 8527 | 8527 | 8527 | 8527 |

| Log likelihood | −2339.473 | −1365.575 | −3713.382 | −4126.047 | −3117.055 |

| Wald Chi Square | 254.425 | 244.203 | 457.890 | 409.291 | 375.764 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-Owned Enterprises | Private Enterprises | High-Level Administrative Cities | Low-Level Administrative Cities | |

| EID | 0.023 *** (0.006) | 0.019 ** (0.008) | 0.011 (0.008) | 0.028 *** (0.006) |

| Scale | 0.515 *** (0.073) | 0.471 *** (0.086) | 0.687 *** (0.085) | 0.510 *** (0.063) |

| Age | −0.075 *** (0.019) | −0.084 *** (0.016) | −0.014 (0.021) | −0.065 *** (0.012) |

| Leverage | −1.148 *** (0.357) | −0.357 (0.386) | −0.765 (0.487) | −0.428 (0.292) |

| Capital | 0.249 *** (0.077) | 0.205 ** (0.093) | 0.236 ** (0.097) | 0.246 *** (0.069) |

| Competition | −0.517 (0.382) | 0.582 (0.445) | −0.713 (0.545) | 0.124 (0.319) |

| Tobin’s Q | −0.019 (0.061) | 0.024 (0.043) | 0.144 ** (0.067) | −0.017 (0.038) |

| Constant | −8.278 *** (1.643) | −8.500 *** (1.720) | −10.843 *** (1.694) | −9.010 *** (1.239) |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 3901 | 4173 | 3040 | 5487 |

| Log likelihood | −2.8 × 103 | −2.3 × 103 | −1.5 × 103 | −3.7 × 103 |

| Wald Chi Square | 407.859 | 212.002 | 210.486 | 390.759 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhong, C. Does Environmental Information Disclosure Affect the Sustainable Development of Enterprises: The Role of Green Innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911064

Hu D, Huang Y, Zhong C. Does Environmental Information Disclosure Affect the Sustainable Development of Enterprises: The Role of Green Innovation. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):11064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911064

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Dameng, Yuanzhe Huang, and Changbiao Zhong. 2021. "Does Environmental Information Disclosure Affect the Sustainable Development of Enterprises: The Role of Green Innovation" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 11064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911064

APA StyleHu, D., Huang, Y., & Zhong, C. (2021). Does Environmental Information Disclosure Affect the Sustainable Development of Enterprises: The Role of Green Innovation. Sustainability, 13(19), 11064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911064