Abstract

Recent advances in the literature regarding local government and governance are demonstrating that models of intermunicipal cooperation are becoming widespread and having an impact on both the organizational dimension and the policy making/service planning side. The success of these arrangements can vary according to several variables such as the regional context, and the services on which is focused the cooperation and the presence/absence of normative constrains that promote these models of cooperation. The aim of this article is to develop a better understanding of a new regional policy focused on area social plans which requires a change in the governance of interorganizational collaborations. This article addresses the gap in the literature on local governance of interorganizational collaborations and area social plans. An empirical study was conducted of four emblematic case studies in one of the most important Italian regions. The results confirm that the new governance of interorganizational collaborations must be characterized by positive interaction between structures, processes, and actors. The results also showed that the presence of certain circumstances such as close ties, many pre-existing relations among the municipalities, and a high level of trust among political parts and administrative offices, appears to smooth the path to success of intermunicipal coordination.

1. Introduction

In order to cope with the challenges arising from the emergence of new social needs as a result of the economic crisis, governments are redefining welfare state provisions as well as the governance models which influence the planning and supply of social services. These changes are occurring in nearly all the nations member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and involve various government levels. In particular, and this is the target of our reflection, it is at the local level that it is possible to observe a significant redefinition in the organization of social policies and, consequently, in the governance models that pertain to this sector of public policies, further characterized by a significant process of decentralization. This devolution of powers, authority, and resources to lower levels has as a consequence the amplification of the fragmentation issue per se that is a characterizing feature of governance systems due to the need to foster and improve specialization. The unavoidable output of this situation is the quest for coordination and cooperation between and within governance levels otherwise, as stated by van Popering-Verkerk and van Buuren [1], every effort to realize governance system tasks could be in vain. From here, our aim is to develop a better understanding of the change in the governance of interorganizational collaboration required by a new regional policy focused on a reorganization of area social plans.

From a scientific perspective, our research is relevant because it fills a gap in the literature on local governance of interorganizational collaborations and area social plans, contributing to the development of broader literature devoted to the analysis of how local governance and government arrangements can determine, through the definition of particular tools of area planning [2,3,4,5], the conditions for failure or success of intermunicipal coordination. In particular, we will inquire why municipalities do (not) enter into forms of cooperation [6,7,8,9,10], what forms this cooperation take, and what the explanations for municipal preferences are [11,12,13]. Our study has proved to be particularly remarkable because, through the analysis of the Italian Piani di Zona’s (area social plans) experience and of their peculiar form of area planning and inter-municipal cooperation, it reveals how the definition of an institutionalized arena (composed of structure, process, and actors) needs the presence of close and routinized relationships among members and a substantial levels of mutual trust, plus the presence of leadership roles, in order to positively respond to external pressure for change. The contextual presence of all these conditions is a valuable indicator about the organizational isomorphism and the degree of adaptability of a governance/government arena [14]. Therefore, this article reveals the importance of the presence of a strong and structured model of governance for interorganizational relationships to the area of planning success. This article is organized as follows: In Section 2, we present a review of the literature; in Section 3, we present the research methodology; in Section 3, we introduce the case of area social plans in the Lombardy Region with regards to the new policy provided by the Regional government, and explain its rationale and its aims; in Section 4, we present and discuss the four case studies; and finally we present our conclusions.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

One of the main aspects that characterize the transformations that are occurring to the social protection systems in Europe is the enforcing process of territorialization which, briefly said, can be defined as the task to bring social services and welfare provisions as close as possible to citizens, trying to enforce the effectiveness and the personalization of the services, to better cope with new social issues [2,5,15]. The transformations in local governance are strictly connected to this process and as a result both of the changes in local government model and of the competencies attributed to public and private actors [16]. More importantly, at least for the purpose of our article, the core of the new model of social governance relies on the need for actors to seek, feed, and guarantee a new strict and effective model of cooperation. As a result of this point of view, the public actor is becoming more and more involved in building this kind of cooperation and partnerships with social actors, third sector, and other local authorities in order to produce new services, and thus employ a course of action that is defined as interaction or building of governance networks [17]. As stated previously, these changes are connected to the process of decentralization that is occurring in various countries, a sort of new trend in administrative development that is redefining the relationships among actors at different levels [6]. This devolution of powers, authority, and resources to lower levels has as a consequence the amplification of the fragmentation issue [18,19] per se that is a characterizing feature of governance systems due to the need to foster and improve specialization and coordination [1,18,20]. Furthermore, the quest for cooperation and collaboration is essential to overcome inefficiencies and shortcomings produced by fragmentation in local governance and government arrangements [7,21].

The quest for institutionalized cooperation at a local level may involve different sectors and experiences, for example, the research of new arrangements in order to revise and control total spending of municipalities such as in the Netherlands case [22], the management of solid waste in rural environments (impacting both the costs of the service and its quality) [23], the impact of private providers in public service delivery such as local road and park services [24], and the role of intermunicipal consortia in different contexts such as Spain or Brazil [25].

From this point of view, the Italian experience can be seen as peculiar because it is characterized by high levels of administrative and social fragmentation that require public actors to confront the dilemma of detecting and defining governance instruments that are able to solve this problem through the enforcement of horizontal [26] or multilevel models of coordination [18,27], using both formal and informal tools [28]. The improvement of intermunicipal cooperation and coordination has become essential, especially for the planning and supply of social services, which, in the Italian case, are a competence of municipalities which often, due to the lack of available resources and the scarce ability in the planning of innovative policies, must pursue new local governance arrangements, and therefore strengthen the dimension and pervasiveness of the area planning [5]. It is known that these cooperative arenas are characterized by the following: (a) a high level of complexity because they are composed of multiple actors and interests [29], (b) a high level of interdependence among partners in order to be more effective they need to develop [4], (c) a desire to develop shared tools in order to solve collective problems and find solutions [29], and (d) the presence of a steady and continuous flow of information between actors, which assures a channel of information and avoid asymmetry among actors [30]. Considering all these variables, the best way to determine the effectiveness of area planning and a cooperative arena is to understand which elements contribute to defining the coordination level and determining the organization’s course of action [31].

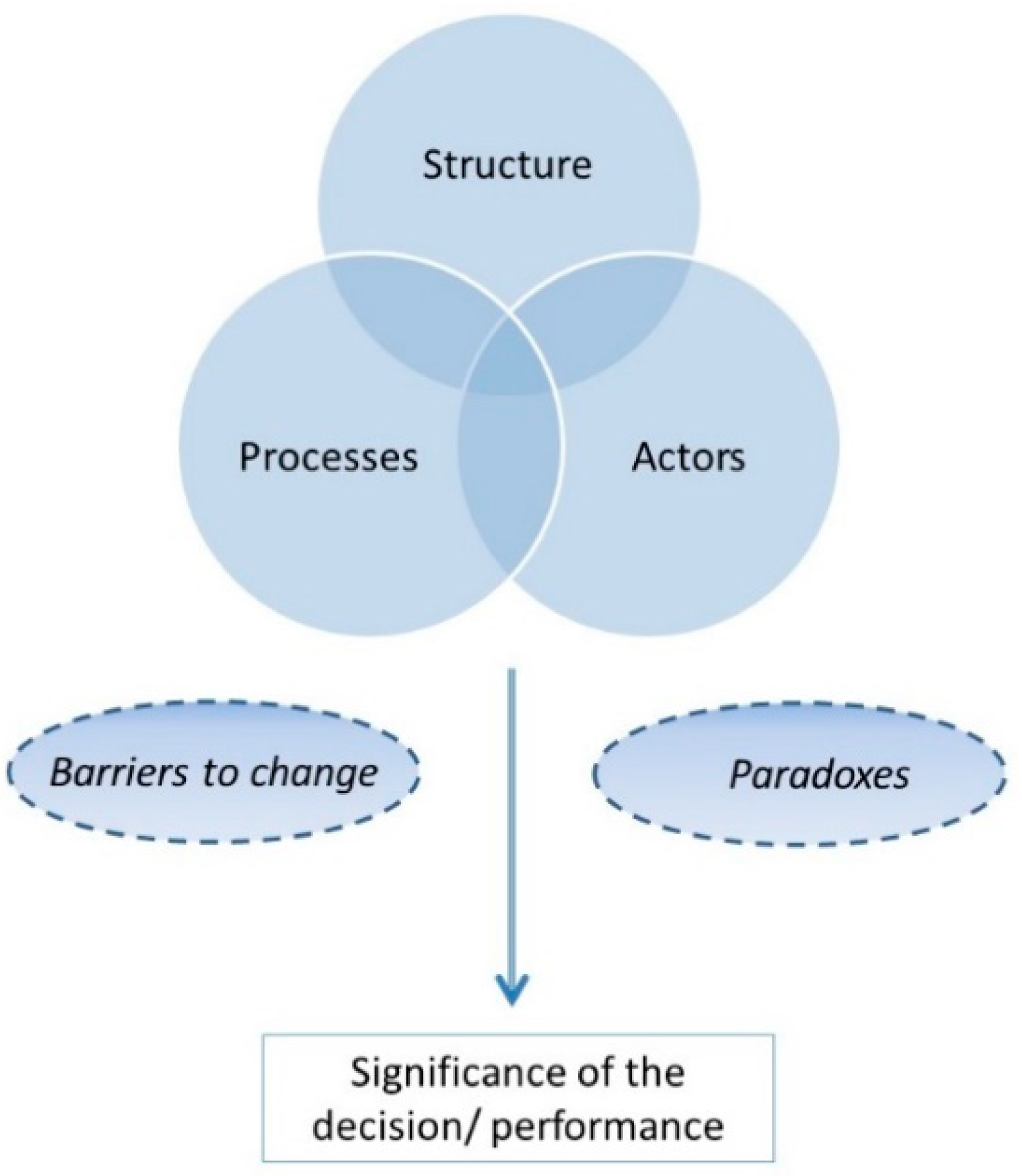

Consequently, our study is precisely focused on the need for municipalities to seek, supply, and guarantee new structures and effective models of cooperation, which bypass the traditional hierarchal organization of authority [32]. Hence, we used an adaptation of the framework (Figure 1) of analysis developed by Vangen et al. [33]. They distinguished three main factors, i.e., structures, processes and actors. Structure is a complex system of interconnected elements which determines the definition of ties and opportunities according to which actors can operate and influence the distribution of power and resources, the agenda setting, the decision-making models, etc. Briefly, talking about structure in connection with the theme of intermunicipal cooperation, means to refer to elements such as the complexity of the relationship among actors and the number and size of municipalities. In particular, it is interesting to ask if complexity is based on a system of weak or strong ties. A second characteristic of structure complexity is the number and size of municipalities; this has an effect on the costs and benefits of cooperation because it involves both the resources that municipalities control and the power exerted by them, according to their size [34,35]. The process aspect is connected to the way in which coordination takes place, how actors cooperate, communicate, make decisions, and share responsibilities. Obviously, the processual dimension is very dynamic and can take different shapes, also within the same governance network, the implication being that some processes can strengthen one actor and damage others, while others provide win-win solutions for all the different actors. Here, the reference is to non-structural relationships that useful for promoting interorganizational collaborations (both formal and informal) such as joint projects, workshops, convening committees, routinized working cooperation, etc. Here, we encounter both formalized mechanisms such as information, coordination, and control mechanisms, and less formalized and “soft” mechanisms [36,37,38]. Finally, when the reference concerns actors, the attention is on a wide array of subjects which include both institutional and non-institutional subjects, for example, politicians, bureaucrats, administrative staff, experts, citizens, associations, and the third sector, as well as profit and non-profit organizations. Furthermore, this heterogeneity finds a straightforward confirmation in the presence of power asymmetries and differences that can pertain both to the organizational level and to the individual partners. Differences in interests and informal relationships can frequently lead to collaboration that does not work in the expected manner, and that is why the presence of leadership that is able to foster trust and cooperation among actors is so important [39,40]. According to Crosby et al. [41], there are four leadership roles, i.e., sponsors, champions, catalysts, and implementers. Finally, our framework must be completed by an evaluation of the performance. Kenis and Provan [42] (p. 442) stated that it is complicated to answer the question “what is performance?” in public networks and ask how performance should be measured. Furthermore, it is essential to consider that in interorganizational collaborations new actors can take the stage and others may leave, thus, weakening the trust level within the network, or a new policy may impinge on what has previously been done, thus, limiting the effectiveness of those choices. Accordingly, much of the research on intermunicipal arrangements have emphasized that the failure of local governance efforts is a more likely alternative to success [43]. For these reasons, we decided to consider performance as the so-called significance of a decision [1]. An act can be defined as a decision if none of the significant actors and partners involved in that decision defect or sabotage the effectiveness of that decision [44]. Finally, along this process it was possible to identify a series of barriers and paradoxes that could be obstacles to successfully reaching a new arrangement.

Figure 1.

Framework of analysis.

3. Methodology and Data

To address the question in this paper, we propose an exploratory research approach based on case study evidence. Case studies are key to understanding phenomena that require a holistic interpretation of structures, actors, and relationships/processes. We have followed an abductive approach to the case studies, since it is valued as an appropriate method for making sense of an unknown situation, through an inference from observed facts. In this case, the research is based on the literature regarding the governance of interorganizational collaborations, and the aim is to understand if it can be complemented or improved with perspectives from exemplar cases. Hence, the decision to use this qualitative methodology is due to its heuristic perspective in the study of the early stages of policy implementation [45]. First of all, the Lombardy Region was selected, because is one of the few regions in Italy that is currently experimenting a new model for the planning and organization of local social services and welfare. In order to identify cases of potential interest from this viewpoint, we tried to map all the territories that had been reported by the regional government as succeeding in the implementation of the new policy. At the same time, we asked the regional government for some cases of emblematic failure of new policy implementation. To enrich the analysis, different data sources (search engines, municipality reports, and publications) were combined to verify if there were other emblematic cases of success or failure in the Lombardy Region with respect to implementing new policy for the establishment of a new area social plan. The result was a number of potentially interesting cases for our research, i.e., ten in total. The municipalities were contacted and asked for materials and documents about the policy and its implementation. We also asked about their availability to be interviewed and studied in depth. After this step, four cases stood out as being particularly relevant to our research purposes (as exemplar cases), providing data and being accessible to researchers. Unfortunately, it was not possible to obtain an interview from a representative of the third sector for each of the four cases, which partially limits the robustness of our qualitative results, but the choice has been to privilege the data homogeneity among the four cases.

The interview outcomes were triangulated, also taking into account other data sources including reports and official written documents, web sites, press releases, archival materials, direct participation in workshops and organizational meetings, and field notes taken after formal and informal meetings. The interviews (see Appendix A) and the meeting participation were carried out between 2017 and 2018 and were analyzed according to a chronological description for each single observed case study [46]. Each interview lasted approximately 90 min. Open-ended questions were used throughout the interviews. All interviews were audiotaped for subsequent transcription and for verification of accurate interpretation. The total number of semi-structured interviews was 36. After all the interviews, they were coded through a codebook based on the categories of structure, processes, actors, barriers, and paradoxes in order to underline the dimensions of interest. The results were submitted to the process of intercoder reliability (which results proved the robustness of the coding effort).

The following interviewees were chosen because of their role in the policy process: the policy makers (officials of the Lombardy Region), the territorial agencies who are in charge of supporting the policy implementation (directors of local health agencies), and the subjects that have to realize the reform (municipalities and area social plans). All this different data enabled us to reconstruct the path of the reform, and therefore to build a chronological description for every single case, using process tracing in order to unfold and explain this path and its effectiveness.

4. Area Social Plans and the Context of Local Change

In order to fully understand this process of reorganization, it is necessary to give a brief overview of the legislative relationship that occurs between the region and the municipalities regarding the definition of social policies (under the framework of the national law which regulates social services). Furthermore, this linkage should be connected to the high level of territorial and administrative fragmentation, which is an issue that characterizes the regional (and national) framework and that deeply affects the organization and supply of social services. The reduction of this fragmentation has been one of the main ideational drivers behind this reform process.

The Italian government tried to reorganize the delivery of social services through the law 328/2000. This law states that Italian municipalities must unite in intermunicipal groupings called Piani di Zona, which are interlocal agreements for the associated planning of services and social interventions of municipalities able to match their resources, and respond to needs, within a limited territorial area. Theoretically this organizational instrument should (a) give small and medium size municipalities the opportunity to provide better services, (b) reduce fragmentation, and (c) boost cooperation. Unfortunately, these demanding goals have not been fully realized and a series of contradictions have characterized this experience. These limitations are further exacerbated by the fact that, in Lombardy, a high level of institutional fragmentation still persists, i.e., a region with more than 10 million inhabitants who are divided into 1512 municipalities (1042 municipalities have less than 5000 inhabitants) and with 98 area social plans in charge of planning and coordinating social services. In Table 1, the state of affairs in Lombardy on 31 December 2017, before the start of the new planning phase, is presented.

Table 1.

Area social plans in Lombardy on 31 December 2017.

The table shows a high level of fragmentation, that, as stated by the Regional Director of the department for Social Services, “limits the ability of municipalities to answer to the challenges provided by the emergence of new social needs, with a high number of area social plans that are frequently responsible for a small number of citizens”. In reaction to this fragmentation, the regional government issued a new policy in December 2017, the Regional Resolution no. 7631, with the aim of activating a process of redefining the area social plan borders, in the words of a regional officer, “by implying a partial top down strategy also based on a mechanism of monetary reward, so as not to infringe on the autonomy of municipalities”. The crucial element of this reform concerns, in particular, the delineation of a new “optimal level” for defining the administrative territorial borders for the supply of social services, which is connected to the number of inhabitants within the administrative borders. Resolution no. 7631 determined that each area social plan should have more than 80.000 inhabitants, with the exception of areas of high population density (in this case the limit was more than 120,000) and of mountain zones (more than 25,000 inhabitants). It is interesting to point out that, currently, 29 out of 98 area social plans do not respect this new threshold. However, for these areas, the reform is a voluntary choice, and therefore they can decide if, when, and with whom to stipulate the new agreement. The regional government gave the area social plans a different type of timeframe to eventually define the new district area. In order to encourage these territorial aggregations, the new form of delivery was based on an innovative (at least for the Lombardy Region) reward mechanism, i.e., the constitution of a new area would be rewarded with a sum of 30,000 euros which must be dedicated to the enforcement of the administrative structure of the area social plan. The definition of a new area social plan then provided access to a second level of contribution (30,000 euro) which was strictly connected to the achievement of three goals of social innovation. These two levels are conceived as strictly connected because a new larger area social plan (in terms of inhabitants), is fundamental to more effective planning and a more efficient administrative structure and is the prerequisite to introducing real innovative elements in the actions promoted at the local level. On the 31 December 2018 only 48 out of 98 area social plans had subscribed to the new policy, of which only three area social plans were the result of a merge between two or more plans. A further 24 plans, even if they had not reached the new limit set by the regional resolution, are currently on stand-by. As stated by a regional officer, “I don’t understand this situation, especially the reason why, despite the monetary incentive, the voluntary aggregation has been a substantial failure”.

5. Case Studies and Discussion

In this section, the four case studies are presented. For all these cases, we applied our research model in order to understand how the change determined by the new policy impacted on interorganizational relationships (Table 2).

Table 2.

Local area plans (before and after).

The local area plan A was characterized by an extremely high level of administrative fragmentation with 51 municipalities, of which 41 were very small with less than 5000 inhabitants. The structure was also characterized by close ties, with many pre-existing relations among the municipalities, with a high level of trust and a strong cultural and territorial identity. The political homophily among the three leading mayors also played a clear role, enabling initial doubts to be overcome and, as stated by a mayor, “a new territorial integration and a scale which allows the planning and the supply capacity of the 51 municipalities involved in the project to be improved”. The processes did not present any particular characteristics, especially as they were based on informal relationships and on the will of all the actors to reach a new intermunicipal agreement. The routinized cooperation among the involved administrative sectors clearly represented an asset in order to reach an agreement, because the main risks and opportunities were previously known and, additionally, there was a high level of trust among the bureaucrats.

Finding an agreement among the political parts was quite straightforward and was reached after only two to three formal meetings. With regards to the actors, it is worthwhile to point out that the path toward a successful application of Resolution no. 7631, was made possible by the coordination efforts of the political leadership which worked to reduce uncertainty among the participants and tried to create as clear a framework as possible for cooperation. In our context, this variable was particularly important for boosting collaboration in an extremely fragmented context where partisan aspects were seen as fundamental to fostering new models of collaboration and reducing transaction costs [47], making more sustainable and effective the cooperation. In addition to the fundamental role of “sponsors”, the National Association of Families of the Mentally Handicapped played an important role as “catalyst”. Over a long period of time, it had developed some important projects in partnership with many of the involved municipalities. As said by the director, “we see this new aggregation as an opportunity to provide new scale and scope in all our projects”. Finally, the efforts to create the new intermunicipal governance model were also supported by the external aid of the university researchers who cooperated directly with the mayors and administrative officers, by playing the role of “champion and orchestrator” [30]. As stated by one mayor, “the role of the university as network orchestrator was crucial. It made interorganizational relationships easier and more profitable by enforcing exchanges between organizations, supporting and transferring knowledge, being committed to field work and so creating a real ‘bridge’ between our organizations”. This aspect is particularly interesting because knowing that the presence of an external actor that is not involved in terms of authority and resource pooling can exert a facilitating role in promoting an agreement about the definition of a complex organizational arrangement. The presence of a sort of “guarantor” is an important asset for promoting and supporting intermunicipal cooperation.

Furthermore, no barriers hindered the path towards the definition of the new network. Only one temporary paradox was observed, when a group of municipalities were initially scared by the possibility of the biggest town playing a dominant role and it was particularly keen on cooperation, innovation, and pooling resources. One mayor said, “on the one hand, their presence and efforts are a very useful asset, on the other hand, we fear that it could dominate our network by controlling the cooperation process”. But, after an initial period of uncertainty and a couple of joint meetings with the support of the university, these municipalities also agreed to join the new network. The performance overall was very positive. The new interlocal agreement was signed before the end of June. As said by the director of local health agency, “you are in time for the first window of opportunity and with a high level of participation from all the actors involved. We congratulate all of you, we are sure that this new model of local government will be an example of best practice for the entire Lombardy Region”.

In case A, the potential risks of failure connected to the high degree of fragmentation and the presence of a big city as the leader of the new intermunicipal cooperation rapidly turned to a positive asset. The political actors, characterized by strong tights as a result of a high level of political homophily, interpreted these elements as an opportunity to overturn the limits of their pre-existing arrangement, i.e., a larger Local Area Plan with a big city as coordinator can have more opportunities to produce more effective policy decisions, strengthen the planning capacity, and gain more external resources.

Differently from the previous case, in case B there was no political leadership, nor political homophily. However, there were close ties and a high level of trust among the administrative offices, developed in previous effective interorganizational collaborations. As stated by a local area plan director, “this high level of trust among partners meant the absence of free rider behavior, and the continuous and active cooperation among all the actors, also by giving partners the opportunity to opt out in the case of dissent on certain decisions without the risk that conflicts become disruptive. All these elements mean that the benefits of cooperation are high and available to all participants”. This is an important aspect because it means that in the “absence” of strong involvement and control by the political part, the administrative side is able to take the lead of an intermunicipal agreement. Broadly speaking, this confirms that in a governance environment the output and efficiency dimensions are more important than political accountability and scrutiny.

In regard to the processes, this case underlines formal planning; the administrative offices were strongly involved in the writing and planning of the formal agreements and paid great attention to their contents. The two mayor assemblies embarked on a path of cooperation which resulted in a series of joint meetings between the two, where common reflections about the needs, problems, and opportunities for cooperation were shared. In March 2018, the two assemblies asked their administrative offices to prepare a study on the pros and cons of a merge between the two area social plans. This assignment started a phase of study in which all the aspects concerning the function of the two area social plans were analyzed. This phase ended with the drafting of a document, produced by a joint committee, in which it emerged that the creation of a new interlocal agreement could be accepted due to the great commonality among the actions and organizational models of the two area social plans. Furthermore, the committee demonstrated the potential benefits produced by this merger in some strategic areas such as effective provision of more specialized services, the empowerment of specific social policy, and more power and strength in potential confrontation with other institutional actors. From our interviews, the idea arose that this choice was not taken simply as a compliance with the law, but as stated by an officer, ”as a way to coordinate and share positive and valuable administrative experiences, organizational models and services which can become a common asset for the new interlocal agreement, and give citizens the opportunity to choose among different and effective services, thus creating an added value compared to the simple sum of the two previous intermunicipal agreements”.. In this process, the administrative officers played a relevant role as “implementers”. The positive interaction between these elements led to a very low degree of resistance to change. In addition, this confirms, as previously observed, the relevance of the pivotal role of administrative officials who are able to solve or anticipate shortcomings, tensions, or conflicts by acting in a preventive way through informal bargaining to define stronger agreements.

Moreover, as stated by one officer, “this opportunity will only work if the definition of the new governance system respects some gradualist criteria and preserves the good aspects which characterize both the previous experiences”. This underlines the essential importance of mutual trust and gradualness in order to improve changes in the realm of intermunicipal cooperation and governance reform.

The performance was positive and a new interlocal agreement was signed in December 2018. Finally, as stated by the director of the local health agency, “The change in this governance model is showing us that it is especially the interplay between informal and procedural interactions that best explains the dynamics and the decision-making outputs in the governance of interorganizational collaborations”.

Case C is quite interesting because it illustrates how the presence/absence of some characteristics such as the level of trust substantiated by an absence of political leadership, the scarcity of previous relationships and the resistance to change, is more relevant than other characteristics for a negative or positive output. Despite a fairly homogenous political homophily, here, there is a low level of trust and weak ties. The political parties started to reflect on the possibility of creating a new network of cooperation in the social sector after the promulgation of the regional law, but they repeatedly failed to find an agreement. Not even the continuous support provided by the university researchers as an external network of orchestrators was able to produce favorable conditions for the agreement. From the point of view of the processes, this case tried a very interesting modality, where the third sector established a common general assembly dedicated to the development of the welfare mix in the territory. However, despite the long preparatory phase and involvement of several institutional and social actors, it was not able to boost the willingness to enforce intermunicipal cooperation among the four areas. The element that finally stopped this first attempt of a merger, was the opposition/doubts expressed by the top administrative officers who labeled the path towards the creation of a new common plan as reckless, in this way slowing down the process until they were able to stop it. The process also encountered several barriers including the fear of change related to new instruments, budget allocation, processes, and services and the fear of change related to new partners and colleagues, as stated by a mayor, “they (the others) didn’t know our territory, our population’s needs”. This stereotyping of potential partners is the tension produced by the clash between the narrative of the “newness” presented as intrinsically good and the reaction caused in the representatives of the old system. This clash contributed to the lock in the system. From here, several cover-up strategies by mayors, who by asking time after time for new planning and new simulations, postponed any possible decisions. These strategies hide difficulties, and therefore limit the opportunity to openly face problems and risks. This case points out two paradoxes. On the one hand, the mayors focused their attention on the strategy, on the other hand, they did not want to postpone the design of the new structure that would implement this strategy. As said by one mayor, “to avoid underestimating the change, we prefer to think simultaneously about the strategy and the structure that supports the strategy implementation. The risk is also that the structure can become too pervasive and lead to a lack of decision-making powers”. The second paradox regards power sharing. The mayors said they wanted a new structure, but at the same time they did not want to devolve power, and therefore did not approve the new structure. As said by a group of mayors, “we are aware that this new organization should have delegated power and resources in order to pursue its goals, but we ask if there is a risk that this devolution leads to losing control of making decisions”. The interactions among all these elements led to the failure of the new interlocal agreement. The four area social plans declined the change and preserved the existing status quo. In this case, the low level of trust and the absence of previous experiences of cooperation, both for the political and the administrative side, created an environment hostile to any form of change. What emerged here is mainly the necessity to preserve the status quo of the involved part, feeding an organizational path dependence that proved to be difficult to dismantle. In particular, it was interesting that an external actor such as the university and a well-organized structured third sector were both not able to promote any type of change.

In case D, the political and bureaucratic parts repeatedly showed a consistent amount of skepticism towards the feasibility of a common interlocal agreement. Various formal and informal talks, in 2018, underlined the differences in organizational and budgetary terms. The two administrative structures did not have any experience of previous interorganizational collaboration, and they also showed a lack of trust with regards to how to promote a possible aggregation. Finally, the political leadership on both parts did not act to reduce the uncertainty of the process or to push for the agreement. The director of the local area plan said, “we are different, with a very different budget allocation, our feeling is that we are really more efficient than others. In addition, we have no previous experience of collaboration”. Furthermore, the direct presence on the “field” of the university counsellors did not produce any concrete results and failed to facilitate the preliminary conditions for an agreement. The resistance to change was quite striking and visible from the very beginning. The willingness to change and modify rooted administrative and planning practices was absent. Here, similar to case C, the role that can be played by path dependence mechanisms which can prevent any sort of change, is particularly evident. In the words of a mayor and a local area plan director, “their plan is of low quality, and we are not able to see any positive aspect to an interorganizational collaboration”. This situation points out some paradoxes. First, one local area plan wanted to play the role of “locomotive”, leading the change, but at the same time it tried to dominate the new agreement, and this led to a low level of trust between the two local area plans. As said by the director of the other area plan, “sometimes we have the sensation that we have to compete against their political machismo. Under these conditions, an effective collaboration is quite impossible”. This means that the efficiency and effectiveness of the potential partner is seen only as a threat and not as an opportunity, the opposite of case A. Second, while they said they were quite favorable to the new agreement, at the same time they asked for a new analysis of costs and benefits in order to assess the sustainability of the process. A group of mayors asked, “we are sure of the pros of this collaboration, but first we would like to be sure of the effective benefits, with an accurate economic evaluation of cost and benefits”. Such choice revealed a low level of trust among partners and the need that an external actor certifies the impossibility to successfully fulfil the project. Third, they said there was a need to define a strategy orientation before structure, but at the same time they disputed the structure. One mayor said, “who will drive the new structure? We think that as our is the biggest territory, the appointment of the president of the new assembly is up to us”. This aspect also underlines the absence of trust, with the need formally expressed to define political and governance arrangements able to guarantee one partner against the other. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that the final outcome was the failure of the new interlocal agreement.

To sum up, our results show two cases of success and two cases of failure (Table 3); as such, it is interesting to observe whether there are any conditions, arising from the interaction between structures, processes, and actors that can explain these different performances. With regards to structure, it is important to highlight that these new aggregations should not be the product of a simple sum of municipalities but, instead, should be the result of an aggregation of actors who have previously collaborated and that are now in a position to promote a new planning model for social policies in an enlarged territory. The presence of pre-existing strong relations, with a good level of trust appears to be critical to a good performance. These characteristics were present in two local area plans but were absent in the other two plans. From this point of view, it seems that the presence of previous experiences of collaboration may help in breaking path dependence in the organizational model and pave the way for the creation of a new intermunicipal agreement. The number and size of the involved municipalities seems to not impact on performance. Both local area plans, with a large number and a small number of municipalities, can reach a positive new agreement, as well as plans that involve both small and medium sized municipalities. Amazingly, processes appear not to be so critical. Neither formal nor informal ties, plans nor workshops and meetings seem to make a difference. Certainly, they work, but they are not crucial. From this point of view, one local area plan showed a very interesting experience, with its structured involvement of the third sector and of all the territorial stakeholders. Nevertheless, the new interlocal agreement was a failure. With regards to actors, our analysis shows how the role of leadership is one of the key ingredients for success. In the first case, we found simultaneously the roles of sponsor, champion, and catalyst. While in the second case, the role of implementers was played by the administrative officers. In the two cases of failure, no leadership roles were present. Finally, it is possible to conclude that even if it is true that it is probable that local governance change failure is a more likely outcome than success, under some conditions this change can succeed. In particular, giving large autonomy to local actors regarding the organizational arrangements appears to be an effective way to implement new policy [11], by improving and strengthening intermunicipal cooperation, in the presence of clear leadership roles and accompanied by pre-existing close relations, and a good level of trust among the involved actors. Political homophily also seems to be an important ingredient for successful cases. Stimulating municipal self-organization when creating a new system of intermunicipal collaboration rather than imposing it from the top, also seems to be a useful way of providing a possible solution for governance fragmentation [19]. Under these circumstances, while monetary incentives play an important role, they are not, however, enough to start the change process.

Table 3.

Comparative evaluation among local area plans.

Our research also outlines a series of barriers that can be obstacles to successfully reaching the goal [26] as follows: conflicting convictions concerning good policy making, which pertain to the possible tensions between old and new models of governance and concern the redefinition of old processes and organizational arrangements; the stereotyping of potential partners; the framing of the situation which pertains to the way in which the change opportunity is presented to actors and that can put pressure on who has the task of implementing changes; fear concerning the risk of failure; and cover-up strategies that can hide difficulties and so limit the opportunity for actors to openly face problems and risks. Finally, the path towards a more integrated intermunicipal collaboration also highlighted the negative effect of some paradoxes that are produced by uncertainty and that are strictly related to the models of cooperation. Paradoxes tell us how difficult it is to achieve cooperation and make it work, and how easy it is to nourish uncertainty.

6. Conclusions

In this article, we have analyzed the experience of the Lombardy Region and the attempt by its regional government to reduce fragmentation and improve coordination in the governance system of social services. To achieve this goal, the Lombardy Region employed both the hard power of policy regulation via Resolution no. 7631 and the soft power of incentive via monetary rewards and complete autonomy as far as the type of aggregation of the new interlocal agreement was concerned. The resolution failed substantially in its initial period of application. Hence, we developed our analysis in order to explain (or even forecast) the motivations that can lead to the failure or success of a policy that aims to implement a change in area social plans. We have produced some interesting novelties for the literature devoted to intermunicipal cooperation and organization of local welfare. In particular, among the observed elements, we show that the presence/absence of two of the elements have a stronger explanatory capacity as compared with the others, for example, the form of the structure with close pre-existing relations and a good level of trust, and the presence of leadership roles, even better if with a high level of political homophily. The case studies showed that if neither of these conditions is in place, the output is failure and this consideration is even more important, if we consider that, as observed in our case studies, the interaction between structures, processes, and actors, produces strong barriers to change.

The evidence confirms that improvement of intermunicipal cooperation in the sector of social services cannot be reached if its main drivers are just rationalization or revision of public spending, which are two elements that frequently nurture negative output instead of opening a phase of better coordination and improvement in services delivery [7,19,22]. The results also confirm that self-organization and autonomy in the definition of cooperative paths are crucial to boosting a successful output [11].

Furthermore, this research identifies the main elements that can act as leverage to stimulate cooperation and coordination in an historical moment that requires new efforts in order to ensure social cohesion [15] and sustainability [48] through the changes in local welfare [49]. Sustainability is not exclusively referred to an economic/budgetary option. It concerns the capacity to define organizational arrangements (in the local welfare realm) that can guarantee the involvement and participation of social forces and local communities, which through their effort, coped with those of institutional actors, are able to mobilize and use community resources to thrive in an environment characterized by change and uncertainty [48,49,50,51]. New social risks and uncertainty require organizational arrangements that can activate different and scattered resources, investing in the generative potential of communities and of welfare mix [52]. From this point of view, this research, among others devoted to the organizational and governance topics [53,54], are essential in order to understand the possible evolutionary paths for local welfare.

Clearly, our research is exploratory, and the collection of more and different data and experiences is needed. It is worthwhile to mention the limits of a small N in terms of effective generalizability, replicability, and reliability. However, we preferred to start with a preliminary enquiry founded on the qualitative richness of the analysis based on a relevant variety of data. The influence that the presence of the university in some organizational meetings had on the interaction among context, setting, and actors should be taken into consideration. Finally, the decision to judge performance by whether the municipalities managed to reach an agreement leads to a partial point of view only, since it does not consider how well the agreements worked in practice and whether the agreed objectives and outcomes were delivered.

However, despite these caveats, these results could be extremely useful to researchers and to practitioners, and they could be applied to various experiences, organizational issues in public administrations, and to several policy fields (not only social policies). In particular, it appears to be essential to foster mutual trust among possible partners, creating organizational conditions such as a clear division of competences, an effective chain of delegation, and a consensual management of monetary resources, which may enable pooling resources and devolving part of authority on a determined policy sector. In addition, the strict interaction between the political and the administrative side may result to be strategic to foster successful cooperation. This point supports the definition of informal practices and agreements that can pave the way for cooperation and positive coordination. These aspects, among others, are the elements that create a direct intervention, and therefore could be useful to practitioners that have to define a managerial intervention to reach an agreement among local institutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P. and E.S.; methodology, P.P. and E.S.; investigation, E.S.; resources, P.P.; data curation, P.P. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, P.P. and E.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions. (Part of the data is contained within the article).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Appendix A. Interviews

| Actors | Lombardy Region | Area Social Plan | Municipality | Local health agency | Non- profit organizations |

| Legal entity | Regional Government | Local government | Public institution | Public institution | Non-profit companies |

| Main activity | To guide, plan, coordinate and control the management of the Regional territory | Local welfare planning | Italian basic administrative division | Health agency in charge of planning, coordination and control of health and social services in each Province | To provide social services |

| Interviews | 4 | 8 | 15 | 4 | 5 |

| Interviewees | Head of Department of Social Services and3 Officers | For each local plan we interviewed the head of local planning and some officers | For each local plan we interviewed one or more Mayors | Deputy Manager and Director | Presidents and Directors |

References

- van Popering-Verkerk, J.; van Buuren, A. Decision-making patterns in multilevel governance: The contribution of informal and procedural interactions to significant multilevel decisions. Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 951–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, L. Citizenship and Governance at a Time of Territorialisation: The Italian Local Welfare between Innovation and Fragmentation. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2014, 23, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Warner, M.E. Inter-municipal cooperation and costs: Expectations and evidence. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 93, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holum, M.L.; Jakobsen, T.G. Inter-municipal cooperation and satisfaction with services: Evidence from the Norwegian Citizen Study. Int. J. Public Adm. 2016, 39, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previtali, P.; Salvati, E. Social planning and local welfare. The experience of the Italian area social plan. Int. Plan. Stud. 2019, 24, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haveri, A. Complexity in local government change. Public Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, P.J.; Denters, B.; Boogers, M.; Sanders, M. Intermunicipal Cooperation in the Netherlands: The Costs and the Effectiveness of Polycentric Regional Governance. Public Adm. Rev. 2018, 78, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Thurmaier, K. Interlocal agreements as collaborations: An empirical investigation of impetuses, norms, and success. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2009, 39, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkin, D.S.; Frederickson, H.G. Metropolitan governance: Institutional roles and interjurisdictional cooperation. J. Urban Aff. 2009, 31, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeRoux, K.; Carr, J.B. Prospects for centralizing services in an urban country: Evidence from eight self organized networks of local public services. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C.; Scholz, J.T. Self-Organizing Governance of Institutional Collective Action Dilemmas: An Overview; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, R.; Deller, S.C.; Halstead, J.M. Alternative methods of service delivery in small and rural municipalities. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previtali, P. The italian administrative reform of small municipalities: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Public Adm. Q. 2015, 39, 548–568. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, A.; Mingione, E.; Polizzi, E. Local Welfare Systems: A Challenge for Social Cohesion. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 1925–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.H. Governance and Governance Networks in Europe. Public Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, C.; Agranoff, R. The limitations of public management networks. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazepov, Y. Rescaling Social Policies: Towards Multilevel Governance in Europe; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.W.; Feiock, R.C. Overcoming the barriers to cooperation: Intergovernmental service agreements. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. Unraveling the Central State, But How? Types of Multi-Level Governance. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2003, 97, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Amsler, L.B. Collaborative Governance: Integrating Management, Politics, and Law. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allers, M.A.; De Greef, J.A. Intermunicipal cooperation, public spending and service levels. Local Gov. Stud. 2018, 44, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Mur, M. Intermunicipal cooperation, privatization and waste management costs: Evidence from rural municipalities. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2772–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindholst, A.C.; Helby Petersen, O.; Houlberg, K. Contracting out local road and park services: Economic effects and their strategic, contractual and competitive conditions. Local Gov. Stud. 2018, 44, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello, L.; Lago-Peñas, S. Local Government Cooperation for Joint Provision: The Experiences of Brazil and Spain with Inter-Municipal Consortia. In The Challenge of Local Government Size. Theoretical Perspectives, International Experience, and Policy Reform; Lago-Peñas, S., Martinez-Vazquez, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Termeer, C.J. Barriers to new modes of horizontal governance: A sense-making perspective. Public Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, G.S.; Mydske, P.K.; Dahle, E. Multi-level coordination of climate change adaptation: By national hierarchical steering or by regional network governance? Local Environ. 2013, 18, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montin, S. Between Fragmentation and Coordination. Public Manag. Int. J. Res. Theory 2000, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovik, S.; Hanssen, G.S. The Impact of Network Management and Complexity on Multi-Level Coordination. Public Adm. 2015, 93, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofoli, D.; Meneguzzo, M.; Riccucci, N. Collaborative administration: The management of successful networks. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, M. Collaborative public management: Assessing what we know and how we know it. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, S.; Klijn, E.H.; Edelenbos, J.; Van Buuren, A. What makes governance networks work? A fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis of 14 Dutch spatial planning projects. Public Adm. 2013, 91, 1035–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangen, S.; Hayes, J.; Cornforth, C. Governing cross-sector, inter-organizational collaborations. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1237–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R.; Tufte, E.R. Size and Democracy; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Denters, B.; Goldsmith, M.; Ladner, A.P.; Mouritzen, E.; Rose, L.E. Size and Local Democracy; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Provan, K.G.; Kenis, P. Modes of network governance: Structure, management and effectiveness. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.H.; Edelenbos, J.; Steijn, B. Trust in governance networks: Its impact on outcomes. Adm. Soc. 2010, 42, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, I.M.; Boenigk, S. Public nonprofit partnership performance in a disaster context: The case of Haiti. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 1385–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, J. Accelerating innovation in local government. Public Money Manag. 2015, 35, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, R. The New Civic Leadership: Place and the co-creation of public innovation. Public Money Manag. 2019, 39, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, B.C.; ‘t Hart, P.; Torfing, J. Public value creation through collaborative innovation. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenis, P.; Provan, K.G. Towards an exogenous theory of public network performance. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A. Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren, A.; Gerrits, L. Decisions as dynamic equilibriums in erratic policy processes: Positive and negative feedback as drivers of non-linear policy dynamics. Public Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousan Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, D. Understanding process tracing. PS Political Sci. Politics 2011, 44, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, E.R.; Henry, A.D.; Lubell, M. Political homophily and collaboration in regional planning networks. Am. J. Political Sci. 2013, 57, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M. The transformative role of the social investment welfare state towards sustainability. Criticisms and potentialities in fragile areas. Sociol. Politiche Soc. 2016, 3, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previtali, P.; Salvati, E. Local Welfare and the Organization of Social Services; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Magis, K. Community resilience: An indicator of social sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Barrientos, A. Welfare regimes and the welfare mix. Eur. J. Political Res. 2004, 43, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previtali, P.; Salvati, E. Governance e Performance nel Welfare Locale. Un’Analisi dei Piani di Zona della Provincia di Pavia. Econ. Aziend. Online 2016, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Salvati, E. Riorganizzare il welfare locale. Il modello del governance network e l’esperienza dei Piani di Zona lombardi. Stu. Org. 2020, 1, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).