1. Introduction

With the global ecological and environmental crisis intensifying, more countries have formulated systematic environmental protection strategies and policies, designed environmental education programs, and encouraged the public’s pro-environmental behavior [

1]. The motive behind the promotion of environmental protection by the states and political parties is both scientific and political. Many political parties have added “green policy” to their programs and guided the sustainable development of society through political and ideological propaganda. However, previous studies have paid little attention to the mechanism of politics, which has played a significant role in environmental protection and needs to play an even greater role.

In recent years, the Chinese ecological environment has continued to deteriorate, which has attracted the attention of the Communist Party of China and raised the degree of the environmental concerns from the departmental level to the national level. As a result, the concept of ecological civilization has been proposed, and large-scale ideological and political education has been carried out. This type of education has taken many forms, including extensive social education through slogans and theoretical education for university students through political courses. Politics-oriented environmental education brings new knowledge on the national environmental strategy to university students and combined with the scientific knowledge brought by the traditional science-oriented education. It has the potential to change the public’s attitude and behavior. Is there a difference in the influence of these two types of education? How does politics-oriented education play a role in shaping public’s pro-environmental behavior? This study, taking Chinese university students as an example, investigates the relationship between environmental politics education and pro-environmental behavior through a large-scale questionnaire survey.

2. Literature Review

The pro-environmental behavior is influenced by many factors [

2,

3], such as education [

4,

5,

6], pro-social conditions [

7,

8], culture [

9], and policy [

10].

Many scholars have a positive attitude to the relationship of pro-environmental knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Fortner and Teates [

11] showed a significant correlation between knowledge and attitude for primary and middle school students regarding the marine environment. Arcury [

12] found a positive correlation between the environmental knowledge of North American consumers and their attitude and behavior. Polonsky et al. [

13] found that environmental knowledge and related attitude act as catalysts for environmentally friendly purchasing behavior. Bang et al. [

14] identified the willingness of consumers to spend more on renewable energy and concluded that there was a positive relationship between knowledge and attitude. Fujii [

15] demonstrated that environmental knowledge has a significant positive effect on the reduction of waste, and the attitude to the economy has a significant positive effect on the reduction of energy consumption, particularly that of electrical resources.

However, some scholars have denied these correlations. Hopper and Nielsen [

16] took garbage collection as an example and showed that environmental attitude had nothing to do with behavior and that people with a positive environmental attitude did not take the initiative to recycle. Tanner and Wölfing Kast [

17] argued that environmental knowledge targeting action can influence environmental behavior, but the knowledge of facts cannot influence the behavior. Sweeney et al. [

18] concluded that an energy-saving attitude does not lead to energy-saving behavior. Paço and Lavrador [

19] suggested that there is no difference between the environmental attitude and behavior of students with different levels of environmental knowledge and that environmental knowledge has little effect on their attitude and behavior. Liu et al. [

20] argued that environmental knowledge is an important distal variable but does not have a significant direct effect on environmentally friendly behavior.

Previous studies have paid attention to the relationship between pro-environmental knowledge, attitude, and behavior and to the influencing factors of pro-environmental behavior. However, few scholars have considered and distinguished the important role of politics-oriented education in pro-environmental behavior. The main contribution of this paper is to investigate the university students’ environmental knowledge in two groups, science-oriented knowledge (SOK) spread by traditional environmental education and politics-oriented knowledge (POK) spread through political education and compare their diverse effects on behavior. The findings will provide a basis for pro-environmental political education in other countries.

3. Theoretical Basis and Research Methodology

3.1. China’s Ecological Environment Protection Strategy, Education, and Knowledge

Since the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in 1972, China has implemented several measures on ecological and environmental protection and management, which can be divided into two stages. The first stage involves the environmental protection strategy led by ministries from 1972 to 2012. The second stage involves the ecological civilization strategy led by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China from 2012 to the present day. Ecological environmental protection has been raised to an unprecedented level and included in the state constitution and also in the constitution of the Communist Party of China.

To implement the ecological environment protection strategy, China’s environmental education was divided into two groups: Science- and politics-oriented environmental education (

Figure 1). The former has been continuing since 1972 and mainly includes elementary, middle, and high school basic education on environmental pollution, wetland functions, garbage classification, and other basic environmental topics. The latter has been intensified since 2012 through vigorously promoted strategies, such as ecological civilization, “five in one” [

1], and “beautiful China” [

2] via central documents, provincial government documents, and various media channels. The former is highly valued in most countries of the world, and its influence on pro-environmental behavior has been previously studied. However, there is a lack of research on the influencing factors of the latter on pro-environmental behavior.

3.2. KAP Theory

Knowledge-Attitude-Practice (KAP) is a behavioral intervention theory and one of the most commonly used models for explaining how personal knowledge and beliefs affect healthy behavior. It was first proposed by the British scientist John Coster in the 1960s. The theory divides the change in human practice into three continuous processes: Acquiring knowledge, producing attitude, and forming practice [

21]. Among them, “knowledge” is the understanding of relevant information, “attitude” is correct belief and positive attitude, and “practice” is behavior.

The model has been used in research in the fields of medicine and public health to explain how personal knowledge and attitude change health practice [

22,

23,

24]. In this study, the KAP model is introduced into the field of sociology of resources and environment to study its impact on pro-environmental behavior based on diverse education.

3.3. Research Assumptions

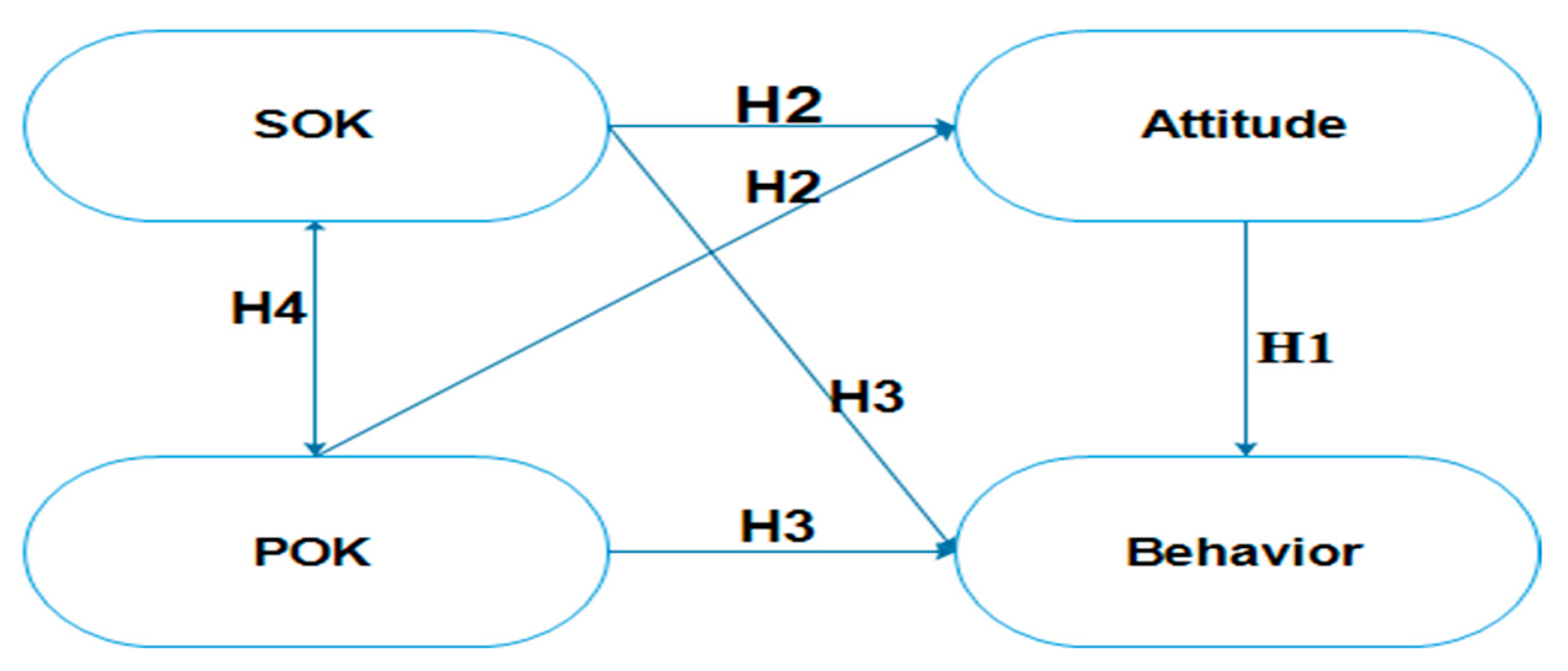

Hypothesis (H1). University students’ pro-environmental attitude has a positive effect on their behavior.

Behavior is the external expression of attitude, and attitude has positive influence on behavior [

5,

25]. Attitude is a person’s evaluation of an object. It expresses a psychological tendency to like or dislike something, or a specific emotional tendency towards something [

26], as a significant predictor for interpreting and promoting behavioral intentions [

27]. Environmental attitude can promote pro-environmental behavior [

3,

28,

29]. For example, consumers with a positive attitude are more likely to buy “green” and energy-efficient products, they do not find it inconvenient to buy green products [

30,

31]. Additionally, the environmental attitude of visitors predicts the timing of their environmental behavior [

32,

33]. Therefore, H1 proposes that the stronger the pro-environmental attitude of university students, the more likely it is that they will transfer that attitude into pro-environmental behavior in their daily life.

Hypothesis (H2). Pro-environmental knowledge has a positive effect on university students’ attitude.

University students’ pro-environmental knowledge can foster a positive environmental attitude [

34,

35,

36,

37]. An environmental attitude changes positively as knowledge increases [

38,

39]. A pro-environmental attitude is more positive for groups with more experience and knowledge about natural resources [

40]. For example, aquarium visits and publications related to marine protected areas can greatly improve the marine environmental protection attitude of visitors by increasing their knowledge [

41]. Knowing more about the environment plays an important role in building attitude towards energy conservation and emissions reduction [

42]. Therefore, H2 proposes that the more relevant knowledge university students master, the stronger attitude they will have.

Hypothesis (H3). University students’ pro-environmental knowledge has a positive effect on their behavior.

If one is ignorant of environmental issues, one cannot consciously care about the environment or act in an environmentally friendly manner [

43]. Environmental knowledge is one of the most powerful predictors of pro-environmental behavior in classical meta-analysis [

44], which can promote pro-environmental behavior [

9,

45]. Therefore, H3 proposes that the more relevant knowledge university students have, the more action they will take to protect the ecological environment.

Hypothesis (H4). SOK and POK reinforce each other.

SOK and POK, as two aspects of promoting pro-environmental knowledge, influence each other. Generally, employees that have a deep understanding of the rules and regulations are more inclined to learn the basic theoretical knowledge, and those who have a good grasp of the relevant theoretical knowledge have a deeper understanding of the rules and regulations. Similarly, university students that have a deeper understanding of political knowledge are more likely to learn and supplement SOK, while those who have a richer SOK have a clearer understanding of POK. Therefore, H4 proposes that SOK and POK promote each other.

Given the above proposed hypotheses, a research framework is developed for this study as shown in

Figure 2 below.

3.4. Questionnaire

Based on KAP theory and the proposed research hypothesis, a questionnaire was prepared from SOK, POK, attitude and behavior (

Figure 3) to carry out the evaluation index and questionnaire design.

Questionnaire distribution and data collection. The questionnaire was issued in December 2015 and completed in March 2016 by the Center of Ecological Civilization (CEC) of China University of Geosciences. The survey was conducted using the snowball sampling method. First, we recruited university students from different provinces. Then, they recruited their former classmates who study in different regions and universities to become the next level of volunteers, and this process was repeated. To ensure the randomness of the sample distribution as much as possible, we set the following rules: Each volunteer cannot recruit more than five people and these volunteers cannot attend university in the same province. We finally had 250 volunteers who distributed the electronic questionnaire through their social network (e.g., Tencent and WeChat).

The survey participants were from approximately 150 universities in 30 provinces except for Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. Among the 14,097 questionnaires that were completed and returned, 693 were invalid and thus excluded based on the data verification requirements, thus, 95.08% of the returned questionnaires (13,404 questionnaires) were valid and used in the model.

3.5. Structural Equation Model

Structural equation model (SEM) is a general statistical modeling technique, which is widely used in many fields, such as psychology, sociology, and economics. SEM is a composite of econometrics, social econometrics, and psychometrics and often used to analyze data with multiple latent and observational variables, as well as examine the effect of a single index on the entire system and the relationship between each index. It is a multivariate statistical technique combining path analysis and factor analysis and has the advantage of being global and systematic, unlike the general regression analysis. Therefore, it can substitute the methods of multiple regression, path analysis, factor analysis, and covariance analysis. This study used SEM as the main analysis tool in the AMOS22.0 statistical software.

4. Research Results and Scientific Discussion

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test

Reliability analysis was done.

Table 1 shows that the Cronbach’s α values of SOK, POK, attitude and behavior vary between 0.6 and 0.7. The Cronbach’s α value of the total scale is 0.792, which is greater than 0.7 and close to 0.8, indicating that the questionnaire showed good reliability.

The validity analysis was passed.

Table 2 shows that the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy is greater than 0.8, and that the P-value of the Bartlett sphericity test is 0.000 at the 1% significance level. These results indicate the validity of the total scale. The result shows that the data of this scale are suitable for factor analysis.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

According to the survey results, the university students’ mastery of SOK is not optimistic. Less than 20% of the students have a good knowledge of environmental pollution, ecological functions, and waste classification, and more than 40% have little or no knowledge (

Table 3). This knowledge is learned in primary school, junior high school, and senior high school and is part of the basic scientific and ecological knowledge. However, university students still exhibit a lack of knowledge in this area, and popular science activities still need to be improved by schools.

University students know more about the policy aspects of ecological civilization. Approximately 50% and 40% of the students are aware of “five-in-one” and “Green GDP (GGDP)”, respectively, which shows that the students have a good understanding of POK (

Table 4). The “five-in-one” strategy has been emphasized frequently in various documents of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, while GGDP is communicated as an academic and professional concept.

University students’ attitude towards courses, future planning efforts, and pro-environmental behavior are weak (

Table 5). More than 90% of students do not support or care that schools offer courses related to ecological civilization, and more than 80% of university students do not know or want to learn about the development direction of combining professional with ecological civilization. Approximately 42.32% and 37.23% of students think that the ecological environment is not very important or not important at all when they choose the city of employment, which shows that university students do not value ecological civilization in future development efforts. This is related to their awareness of the ecological environment. More than 80% of students are not too worried or not worried at all about the overall ecological environment of the country.

Most university students practice pro-environmental behavior (

Table 6). Approximately 55% of students have participated in ecological civilization activities organized by school clubs, but the vast majority of students do not have a high degree of recognition of these activities. More than 90% of students are willing to take part in ecological public welfare activities, and nearly 30% of them have already taken part in those activities. More than 90% of university students publicize their knowledge of ecological civilization to others, which indicates that university students gradually realize the importance of communicating new ideas. Garbage classification used to be a poor behavior in China, and only 10% of university students pay constant or frequent attention to it.

4.3. Structural Equation Model Results

According to the data presented in

Table 7, among the measures of absolute fit indices, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) is 0.972, which is in accordance with the fitness standard (>0.90) and indicates that the model path graph has a good degree of adaptation to actual data. The adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) of 0.958 meets the fitness criterion (>0.90), and the AGFI estimate is usually less than the GFI estimate in the model estimate. The root mean square residual (RMR) of 0.036 meets the fitness criterion (<0.05), and the model is acceptable, the smaller the value of RMR, the better. The value of the standardized RMR (SRMR) is 0.038, which meets the fitness criterion (<0.05). The value of root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is usually considered the most important fitness indicator. When RMSEA is less than 0.05, the model has excellent fitness. RMSEA between 0.05 and 0.08 means the fitness of the model is satisfactory. The RMSEA of 0.052 in

Table 7 indicates that the fitness of the model is satisfactory. In the incremental fit measures index group, all the five indices are in accordance with the adaptation standard, which indicates that the fit degree of the model was good. In the parsimonious fit measures index group, the estimated values of the indices are all greater than 0.5 and thus meet the fitness standard, indicating that the model results are in an acceptable range.

There are significant correlations among SOK, POK, attitude, and behavior (

Figure 4 and

Table 8). The standardized path coefficient is the correlation coefficient, which measures the correlation between the two variables. SOK has a significant positive impact on pro-environmental attitude, with the path coefficient of 0.565, which means that the more SOK the students master, the higher the degree of pro-environmental attitude will be. SOK also has direct and indirect effects on behavior. SOK has a direct and positive effect on pro-environmental behavior with a path coefficient of 0.137. At the same time, SOK has an effect on behavior through the variable of attitude, and this standardized indirect path coefficient is 0.259.

POK has a negative impact on attitude with the path coefficient of −0.201 (

Table 8), which means that the increase in POK will create a less positive attitude towards the environment. The standardized indirect path coefficient between POK and behavior is −0.092. POK indirectly influences behavior through attitude, and the indirect effect of this path is a weak negative effect. Although POK has a negative effect on attitude, it has a significant positive effect on behavior with the path coefficient of 0.432. The path coefficient of behavior for POK is larger than that for SOK.

Attitude has a significant positive impact on behavior, and the path coefficient is 0.459 (

Table 8). In addition, note that the correlation coefficient between SOK and POK is 0.75, which means that they are positively related to each other, thereby showing the fusion of the knowledge groups.

4.4. Scientific Discussion

SOK can, directly and indirectly, influence behavior, and the latter has more influence than the former. On the one hand, SOK significantly affects pro-environmental attitude, and indirectly affects behavior. The effect of SOK on attitude is obvious, which is usually manifested by long-term moral influence, enhancing university students’ environmental protection beliefs [

46], and indirectly influencing their pro-environmental behavior [

47]. This indirect effect means that SOK is easily absorbed by individuals, translated into individual environmental attitude, and promotes pro-environmental behavior [

48]. Therefore, schools should impart pro-environmental knowledge, which is widely accepted in many countries [

49,

50]. It not only increases environmental awareness among students [

51], but also promotes pro-environmental behavior [

52,

53,

54]. On the other hand, SOK can directly promote to a generation the positives of pro-environmental behavior. The knowledge learned in the class is mostly fragmented and theoretical, thus, students may perceive it as less relevant to life, hence, this type of knowledge has a lower direct impact on pro-environmental behavior [

55]. However, its indirect influence on behavior through attitude is stronger [

56]. Therefore, it is important to improve university students’ SOK and enhance their pro-environmental attitude.

POK has a negative impact on attitude but has a significant direct positive impact on pro-environmental behavior. The government’s encouraging policies can significantly improve audience participation, especially in the short term [

57]. Therefore, POK has a more direct and positive effect on pro-environmental behavior than SOK. However, POK is a “top-down” policy constraint, meaning that its command and control is effective, but the initiative to accept it is limited [

10], thus, it cannot improve attitude.

Attitude has a direct and positive effect on pro-environmental behavior. People with a positive environmental attitude are more likely to help solve environmental problems [

58]. For example, these particular people are more likely to buy environmentally friendly products [

29,

39,

59] and regularly participate in environmental activities [

60]. Attitude is a more powerful promoter of pro-environmental behavior than knowledge, and attitude shapes behavior by intention [

61]. A strong attitude creates an internal drive to develop behavioral guidelines [

62].

There is a significant positive correlation between SOK and POK, which indicates that they support each other. SOK is represented by “bottom-up” moral influence, while POK is represented by “top-down” policy constraints, which should expand the comprehensive reform of “top” and “bottom” coordination [

63]. The distribution of pro-environmental knowledge based on the SOK and POK aspects should be strengthened, and the concrete understanding of general knowledge should be combined with the macro guidance of policy knowledge to enrich pro-environmental education.

5. Conclusions

Based on China’s eco-environmental protection strategy in the new era, the pro-environmental knowledge of university students can be divided into science-oriented knowledge spread by traditional environmental education and politics-oriented knowledge spread through political education. In order to study the different impacts of these two types of education on pro-environmental behavior, a questionnaire was conveyed to more than 14,000 students from 152 universities in China via the snowball method to analyze the conduction path of knowledge, attitude, and behavior using the structural equation model. This method closes the gap caused by neglecting the influence of political power on pro-environmental behavior in previous studies and provides a reference for pro-environmental education in other countries.

The main conclusions of this study are as follows.

Compared to SOK, POK has a quicker and stronger effect on pro-environmental behavior. Because China’s political party system determines that the government’s encouraging policies can significantly improve university students’ participation, especially in the short term. It also shows that ideological and political course, that is, the integration of national policies into the classroom, has been widely implemented and achieved obvious results in China. Therefore, if pro-environmental behavior is expected to improve rapidly, politics education should be strengthened through courses, TV, mobile phones, banners, and APPs to support the understanding and mastery of POK.

SOK has a positive effect on attitude, but POK has a negative impact on attitude because the former is obtained from the education received from childhood and comes from the bottom-up path, which is easier to form a strong sense of identity. But the latter is the knowledge instilled from top to bottom, which may not be understood enough by university students. Thus, the characteristics of POK should be enhanced. The SOK in primary, middle, and high schools, as well as in daily life, has been deeply rooted in the minds of every student, while POK has only been trumpeted in recent years in China, thus, university students do not have a strong sense of POK. Using new media technologies to make policy education work (e.g., “internet + education,” watching movies, group discussions, and brainstorming) will promote students’ understanding and recognition of POK.

There is a significant positive correlation between SOK and POK. Therefore, the integrated education of SOK and POK should be promoted. SOK should continue to be taught combined with POK. They can together, directly and indirectly, promote the pro-environmental behavior of university students. On the one hand, university students should be encouraged to participate in extracurricular knowledge competition to understand the basic knowledge of the ecological environment, such as garbage classification, water resources, land resources, atmosphere, and biodiversity, as well as their influencing factors. On the other hand, primary school students who will be university students in about ten years should be encouraged to participate in Policy Knowledge Q and A activities to advance their contact time of POK, so that they have more time to understand national policies and enhance their recognition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and E.W.; methodology, R.W.; software, T.J. and K.Z.; validation, R.W., T.J. and E.W.; formal analysis, J.C.; investigation, R.W. and R.Q.; resources, J.C.; data curation, R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W. and T.J.; writing—review and editing, R.W. and T.J.; visualization, R.Q.; supervision, J.C.; project administration, J.C. and R.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 14CKS014 and Ministry of Education Philosophy and Social Sciences Fund, grant number. 19YJZH168.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 14CKS014), Ministry of Education Philosophy and Social Sciences Fund (No.19YJZH168), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan). The authors would like to thank the Chinese college students who took part in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in collection, analyses, or interpretation of data in the manuscript, and the authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Filho, L.W.; Brandli, L.L.; Becker, D.; Skanavis, C.; Kounani, A.; Sardi, C.; Papaioannidou, D.; Paço, A.; Azeiteiro, U.; de Sousa, L.O.; et al. Sustainable Development Policies as Indicators and Pre-conditions for Sustainability Efforts at Universities: Fact or Fiction? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuthnott, K.D. Education for Sustainable Development beyond Attitude Change. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2009, 10, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levy, B.L.M.; Marans, R.W. Towards a Campus Culture of Environmental Sustainability: Recommendations for a Large University. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2012, 13, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana-Ríos, A.; Pozo-Llorente, M.T.; Poza-Vilches, M.D.F. Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Teaching Practice in Secondary Schools Located in Natural Protected Areas from the Perception of Students: The Case of Níjar Fields (Almería—Spain). Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2017, 237, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening Due to Environmental Education? Environmental Knowledge, Attitudes, Consumer Behavior and Everyday Pro-Environmental Activities of Hungarian High School and University Students. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, H. Do Pro-Social Students Care More for the Environment? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 761–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, T.M.; Sullivan, A.V.; Stapp, J.R. Campus Prosociality as a Sustainability Indicator. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chwialkowska, A.; Bhatti, W.A.; Glowik, M. The Influence of Cultural Values on Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H. System Construction of Polycentric Governance in Local Universities. Univ. Educ. Sci. 2012, 06, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fortner, R.W.; Teates, T.G. Baseline Studies for Marine Education: Experiences Related to Marine Knowledge and Attitudes. J. Environ. Educ. 1980, 11, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcury, T. Environmental Attitude and Environmental Knowledge. Hum. Organ. 1990, 49, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Grau, S.L.; Garma, R.; Ferdous, A.S. The Impact of General and Carbon-Related Environmental Knowledge on Attitudes and Behaviour of Us Consumers. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.K.; Ellinger, A.E.; Hadjimarcou, J.; Traichal, P.A. Consumer Concern, Knowledge, Belief, and Attitude to-Ward Renewable Energy: An Application of the Reasoned Action Theory. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S. Environmental Concern, Attitude toward Frugality, and Ease of Behavior as Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behavior Intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.R.; Nielsen, J.M. Recycling as Altruistic Behavior: Normative and Behavioral Strategies to Expand Participation in a Community Recycling Program. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Kast, S.W. Promoting Sustainable Consumption: Determinants of Green Purchases by Swiss Consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Kresling, J.; Webb, D.; Soutar, G.N.; Mazzarol, T. Energy Saving Behaviours: Development of a Practice-Based Model. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, A.M.F.D.; Lavrador, T. Environmental Knowledge and Attitudes and Behaviours Towards Energy Consumption. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How Does Environmental Knowledge Translate into Pro-environmental Behaviors? The Mediating Role of Environmental Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, A.; Dowling, M. Knowledge and Attitudes of Mental Health Professionals in Ireland to the Concept of Recovery in Mental Health: A Questionnaire Survey. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 16, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazrou, S.; Saddik, B.; Jradi, H. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Saudi Physicians Regarding Cervical Cancer and the Human Papilloma Virus Vaccine. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharagozlou, M.; Afrough, R.; Malekzadeh, I.; Tavakol, M. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of General Practitioners and Pediatricians Regarding Food Allergy in Iran. Rev. Fr. Allergol. 2019, 59, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastva, A.; Phadnis, S.; Rao, N.K.N.; Gore, M. A Study on Knowledge and Self-Care Practices about Diabetes Mellitus among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus at-Tending Selected Tertiary Healthcare Facilities in Coastal Karnataka. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 8, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shafiei, A.; Maleksaeidi, H. Pro-Environmental Behavior of University Students: Application of Protection Motivation Theory. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, E. Research Status and Development Trend of the Relationship between Attitude and Behavior. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 15, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iozzi, L.A. What Research Says to the Educator: Part Two: Environmental Education and the Affective Domain. J. Environ. Educ. 1989, 20, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young Consumers’ Intention Towards Buying Green Products in a Developing Nation: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Cleaner Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting Consumers Who Are Willing to Pay More for Environmentally Friendly Products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malik, C.; Singhal, N. Consumer Environmental Attitude and Willingness to Purchase Environmentally Friendly Products: An SEM Approach. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2017, 21, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding and Developing Visitor Pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untaru, E.N.; Epuran, G.; Ispas, A. A Conceptual Framework of Consumers’ Pro-Environmental Attitude and Behaviours in the Tourism Context. Bull. Transylv. Univ. Brasov Ser. V: Econ. Sc. 2014, 7, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escario, J.-J. Heterogeneity in the Association between Environmental Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Multilevel Regression Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escario, J.-J.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, C. Analyzing Differences between Different Types of Pro-environmental Behaviors: Do Attitude Intensity and Type of Knowledge Matter? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaiser, L.; Briones, M.S.; Hayden, F.G. Performance of Virus Isolation and Directigen® Flu a to Detect Influenza a Virus in Experimental Human Infection. J. Clin. Virol. 1999, 14, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H.; Huang, G.W. The Influence of Recreation Experiences on Environmentally Responsible Behavior: The Case of Liuqiu Island, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Taylor, N. Strick Wine Consumers’ Environmental Knowledge and Attitudes: Influence on Willingness to Purchase. Int. J. Wine Res. 2009, 1, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flamm, B. The Impacts of Environmental Knowledge and Attitudes on Vehicle Ownership and Use. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2009, 14, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, H.O.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Oliveira, H.M.F.; Pardal, M.A. Conserving Brazilian Sardine: Fisher’s Attitudes and Knowledge in the Marine Extractive Reserve of Arraial Do Cabo, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Fish. Res. 2018, 204, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyles, K.J.; Pahl, S.; White, M.P.; Morris, S.; Cracknell, D.; Thompson, R.C. Towards a Marine Mindset: Visiting an Aquarium Can Improve Attitudes and Intentions Regarding Marine Sustainability. Visit. Stud. 2013, 16, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Pan, W. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards Zero Carbon Buildings: Hong Kong Case. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and Social Factors That Influence Pro-environmental Concern and Behaviour: A Review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Filimonau, V. The Effect of National Culture on Pro-environmental Behavioural Intentions of Tourists in the UK and China. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, J.A.P.D.M.; Gouveia, V.V.; De Souza, G.H.S.; Milfont, T.L.; Barros, B.N.R. Emotions toward Water Consumption: Conservation and Wastage. Rev. Latinoam. de Psicol. 2016, 48, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carmi, N.; Arnon, S.; Orion, N. Transforming Environmental Knowledge into Behavior: The Mediating Role of Environmental Emotions. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C. How Do Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Sensitivity, and Place Attachment Affect Environmentally Responsible Behavior? An Integrated Approach for Sustainable Island Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K. A Vision on the Role of Environmental Higher Education Contributing to the Sustainable Development in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplowitz, M.D.; Levine, R. How Environmental Knowledge Measures up at a Big Ten University. Environ. Educ. Res. 2005, 11, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, M.J.; Greasley, S.; John, P.; Richardson, L. Can We Make Environmental Citizens? A Randomised Control Trial of the Effects of a School-Based Intervention on the Attitudes and Knowledge of Young People. Environ. Polit. 2010, 19, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, M. The Effect of Summer Environmental Education Program (Seep) on Elementary School Students’ Environmental Literacy. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Gbadamosi, T.V. Effect of Service Learning and Educational Trips Instructional Strategies on Primary School Pupils’ Environmental Literacy in Social Studies in Oyo State, Nigeria People. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mullenbach, L.E.; Green, G.T. Can Environmental Education Increase Student-Athletes’ Environmental Behaviors? Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto-Martell, E.A.; McNeill, K.L.; Hoffman, E.M. Connecting Urban Youth with their Environment: The Impact of an Urban Ecology Course on Student Content Knowledge, Environmental Attitudes and Responsible Behaviors. Res. Sci. Educ. 2011, 42, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.-E.; Lee, E.A.; Ko, H.R.; Shin, D.H.; Lee, M.N.; Min, B.M.; Kang, K.H. Korean Year 3 Children’s Environmental Literacy: A Prerequisite for a Korean Environmental Education Curriculum. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2007, 29, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N. Research on the Effectiveness of Government Supportive Policies in Promoting the Development of Cross-Border Electronic Commerce—From the Perspective of Complex Network. Zhejiang Soc. Sci. 2016, 10, 57, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dresner, M.; Handelman, C.; Braun, S.; Rollwagen-Bollens, G. Environmental Identity, Pro-environmental Be-Haviors, and Civic Engagement of Volunteer Stewards in Portland Area Parks. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 991–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arı, E.; Yılmaz, V. Effects of Environmental Illiteracy and Environmental Awareness among Middle School Students on Environmental Behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 19, 1779–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, D.; Pe’er, S.; Yavetz, B. Environmental Literacy of Youth Movement Members—Is Environmentalism a Component of Their Social Activism? Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 486–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of Goal-Directed Behavior: Attitudes, Intentions, and Perceived Behavioral Control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Croyle, R.T. Attitudes and Attitude Change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1984, 35, 395–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X. Top-down and ‘Bottom-up’ in Deepening the Comprehensive Reform of Higher Education. China High. Educ. Res. 2016, 6, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).