Bridging Gaps in Minimum Humanitarian Standards and Shelter Planning by Critical Infrastructures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ: How can existing humanitarian standards and shelter planning be improved by an extension on the topic of critical infrastructure?

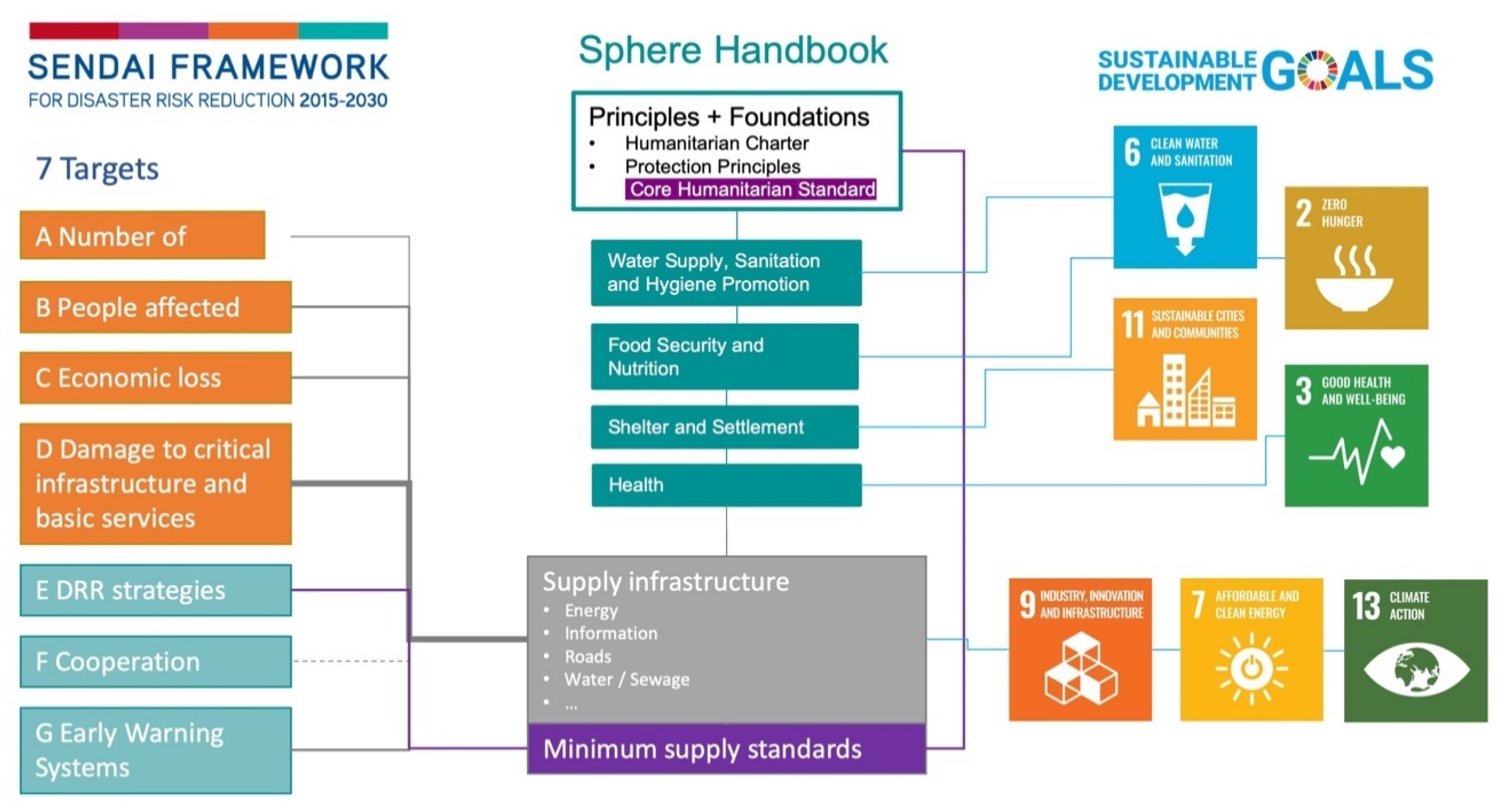

- RQ 1: Why is there a gap within minimum supply standards concerning certain basic infrastructure services?

- RQ 2: Which role and characteristic do critical infrastructure play in the literature related to disaster risk management and shelter planning?

- RQ 3: Which role and characteristic do critical infrastructure play in a humanitarian standard guideline—the Sphere handbook?

- RQ 4: How can critical infrastructure become a cross-cutting topic for both industrialised and developing country contexts?

2. Brief State of the Art and Identification of the Gap within Minimum Supply Standards Concerning Certain Basic Infrastructure Services

2.1. Sheltering, Housing and Migration as a Background

2.2. Infrastructure and Logistics within the Shelter Topic

2.3. Basic Services and Critical Infrastructure in the Shelter Topic

2.4. Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Aid

2.5. Infrastructure as a Topic within the Broader Context of Disaster Risk Reduction

3. Investigation of the Role of Critical Infrastructure in the Sphere Handbook

- Contingency/disaster/emergency management, security

- Energy (electricity, heating, etc.)

- Finance and insurance

- Governance and administration, regulation

- Information and communication

- Transport and logistics

4. Review of the Links between Critical Infrastructures, Shelter Planning and the Sendai Framework

5. Discussion of Conceptual Gaps and Opportunities for a Cross-Cutting Topic for Both Industrialised and Developing Country Contexts

5.1. Connecting Different Notions of Security, Risk and Resilience

5.2. Preparedness Stimulated by Critical Infrastructure Failures

“Besides basic income and resources, the freedoms to enjoy essential health, basic education, shelter, physical safety, and access to clean water and clean air are vitally important” (Ogata-Sen 2003)

5.3. Shelter Planning Background and Focus

5.4. Advancing Existing Risk Management Guidelines on Aspects of Resilience and Minimum Supply

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Degler, E.; Liebig, T.; Senner, A.-S. Integrating refugees into the Labour Market—Where does Germany Stand? ifo DICE Rep. 2017, 15, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhard, S.; Lenz, A.; Seibel, W.; Roth, F.; Fatke, M. Latent hybridity in administrative crisis management: The German refugee crisis of 2015/16. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogumil, J.; Hafner, J.; Kastilan, A. Städte und Gemeinden in der Flüchtlingspolitik: Welche Probleme gibt es-und wie kann man sie lösen? Studie; Stiftung Mercator: Essen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Auswärtiges Amt. Strategie des Auswärtigen Amts zur Humanitären Hilfe im Ausland 2019–2023; Auswärtiges Amt: Berlin, Germany, 2019; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Speth, R.; Becker, E. Zivilgesellschaftliche Akteure und die Betreuung geflüchteter Menschen in deutschen Kommunen. In Opusculum; Maecenata Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2016; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Greussing, E.; Boomgaarden, H.G. Shifting the refugee narrative? An automated frame analysis of Europe’s 2015 refugee crisis. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 43, 1749–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBK. Neue Strategie zum Schutz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland; BBK: Bonn, Germany, 2010; p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Hassel, A.; Wagner, B. The EU’s ‘migration crisis’: Challenge, threat or opportunity. In Social Policy in the European Union: State of Play; European Trade Union Institute (ETUI): Brussels, Belgium, 2016; pp. 61–92. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IAEG-SDGs—Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators. SDG Indicators. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/71/313 E/CN.3/2018/2; United Nations Statistical Commission: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Fekete, A. Common criteria for the assessment of critical infrastructures. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2011, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dierich, A.; Tzavella, K.; Setiadi, N.; Fekete, A.; Neisser, F. Enhanced crisis-preparation of critical infrastructures through a participatory qualitative-quantitative interdependency analysis approach. In Proceedings of the ISCRAM 2019 Conference Proceedings, ISCRAM Conference, Valencia, Spain, 19–22 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams, D. The barriers to environmental sustainability in post-disaster settings: A case study of transitional shelter implementation in Haiti. Disasters 2014, 38, S25–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, I. What have we learned from 40 years’ experience of Disaster Shelter? Environ. Hazards 2011, 10, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.; Hamza, M.; Oliver-Smith, A.; Renaud, F.; Julca, A. Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Nat. Hazards 2010, 55, 689–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D. The road to military humanitarianism: How the human rights NGOs shaped a new humanitarian agenda. Hum. Rights Q. 2001, 23, 678–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davey, E.; Borton, J.; Foley, M. A History of the Humanitarian System: Western Origins and Foundations; Overseas Development Institute Humanitarian Policy Group: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crawley, H. Managing the unmanageable? Understanding Europe’s response to the migration ‘crisis’. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 9, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slominski, P.; Trauner, F. How do member states return unwanted migrants? The strategic (non-) use of ‘Europe’during the migration crisis. JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud. 2018, 56, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtnich, M. Shifting Shelters Migrants, Mobility and the Making of Open Centers in Malta. Structures of Protection? Rethinking Refugee Shelter; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 39, p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Liebe, U.; Meyerhoff, J.; Kroesen, M.; Chorus, C.; Glenk, K. From welcome culture to welcome limits? Uncovering preference changes over time for sheltering refugees in Germany. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftheriadou, M. Fight after flight? An exploration of the radicalization potential among refugees in Greece. Small Wars Insurg. 2020, 31, 34–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, D. Anti-Shelter and the Spectacle of Deterrence. Structures of Protection? Rethinking Refugee Shelter; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 39, p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Jahre, M.; Persson, G.; Kovács, G.; Spens, K.M. Humanitarian logistics in disaster relief operations. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2007, 37, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wassenhove, L.N. Humanitarian aid logistics: Supply chain management in high gear. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2006, 57, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, L.; Ramesh, A.; Sridharan, R. Humanitarian supply chain management: A critical review. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2012, 13, 498–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, S.; Sen, A. Human Security NOW; Commission on Human Security: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- Sphere Association. The Sphere Handbook, Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response, 4th ed.; Sphere Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, C.H.; Koenig, K.L.; Lewis, R.J. Implications of hospital evacuation after the Northridge, California, earthquake. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.V.; Polatin, P.B.; Hogan, D.; Downs, D.L.; North, C.S. Needs assessment of Hurricane Katrina evacuees residing temporarily in Dallas. Community Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, N.Y.; Hamada, M. Evacuation behavior and fatality rate during the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake and tsunami. Earthq. Spectra 2015, 31, 1237–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, E.Z.; Habert, G. Global or local construction materials for post-disaster reconstruction? Sustainability assessment of twenty post-disaster shelter designs. Build. Environ. 2015, 92, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen, A. Emergency shelter topologies: Locating humanitarian space in mobile and material practice. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2014, 32, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Apte, A. Humanitarian logistics: A new field of research and action. Found. Trends Technol. Inf. Oper. Manag. 2010, 3, 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchon, S. The Vulnerability of Interdependent Critical Infrastructures Systems: Epistemological and Conceptual State-of- the-Art; Ispra: Institute for the Protection and Security of the Citizen: Rome, Italy; Joint Research Centre: Brussels, Belgium; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lauwe, P.; Harmon, C.; Pratt, A.; Gorka, S. The protection of critical infrastructure within Germany. In Toward a Grand Strategy against Terrorism; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 328–340. [Google Scholar]

- Seybold, J.; Hemmert-Seegers, C.; Solarek, A. Schlussbericht—Verbundprojekt: “Katastrophenschutz-Leuchttürme als Anlaufstelle für die Bevölkerung in Krisensituationen“—Teilvorhaben: Einbindung von Medizinischen Einrichtungen in das Konzept der Katastrophenschutz-Leuchttürme; CHARITÉ—Universitätsmedizin: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ohder, C.; Sticher, B.; Geißler, S.; Schweer, B. Bürgernaher Katastrophenschutz aus Sozialwissenschaftlicher und Rechtlicher Perspektive. Bericht der Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Recht Berlin zum Forschungsprojekt “Katastrophenschutz-Leuchttürme als Anlaufstellen für die Bevölkerung in Krisensituationen”; Kat-Leuchttürme: Berlin, Germany, 2015; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Bross, L.; Krause, S.; Wannewitz, M.; Stock, E.; Sandholz, S.; Wienand, I. Insecure security: Emergency water supply and minimum standards in countries with a high supply reliability. Water 2019, 11, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bundesministerium des Innern. Konzeption Zivile Verteidigung (KZV); Bundesministerium des Innern: Berlin, Germany, 2016; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance. Sicherheit der Trinkwasserversorgung: Teil 1: Risikoanalyse; Grundlagen und Handlungsempfehlungen für Aufgabenträger der Wasserversorgung in den Kommunen; BBK—Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bross, L.; Wienand, I.; Krause, S. Sicherheit der Trinkwasserversorgung: Teil 2: Notfallvorsorgeplanung; Grundlagen und Handlungsempfehlungen für Aufgabenträger der Wasserversorgung in den Kommunen. In Praxis im Bevölkerungsschutz; BBK—Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sayyed, M.A.; Gupta, R.; Tanyimboh, T. Modelling pressure deficient water distribution networks in EPANET. Procedia Eng. 2014, 89, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rinaldi, S.M.; Peerenboom, J.P.; Kelly, T.K. Identifying, Understanding, and analyzing critical infrastructure interdependencies. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2001, 21, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pescaroli, G.; Alexander, D. Critical infrastructure, panarchies and the vulnerability paths of cascading disasters. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neisser, F.; Pohl, J. “Kritische Infrastrukturen” und “material turn”. Eine akteur-netzwerktheoretische Betrachtung. Berichte Geogr. Landeskd. 2013, 87, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- US Government. The President’s Commission on Critical Infrastructure Protection (PCCIP); Executive Order 13010; US Government: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Moteff, J. Risk Management and Critical Infrastructure Protection: Assessing, Integrating, and Managing Threats, Vulnerabilities and Consequences; A final report from SEMA’s Assignment on Critical Societal Dependencies; Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MSB—Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency. A Summary Version of the Report: If one Goes Down—Do all Go Down? MSB—Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency: Karlstad, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNISDR. Technical Guidance for Monitoring and Reporting on Progress in Achieving the Global Targets of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (New Edition); United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- UN/ISDR. Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters (HFA); United Nations UN/ISDR—Inter-Agency Secretariat of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Yokohama strategy and plan of action for a safer world. Guidelines for natural disaster prevention, preparedness and mitigation. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Natural Disaster Reduction, Yokohama, Japan, 23–27 May 1994. [Google Scholar]

- NOTA—Rathenau-Instituut. Stroomloos: Kwetsbaarheid van de Samenleving, Gevolgen van Verstoringen van de Elektriciteitsvoorziening (Blackout. Vulnerability of Society and Impacts of Electricity Supply Failure); Rathenau Instituut: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1994; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Krings, S. Dear Neighbours … A comparative exploration of approaches to managing risks related to hazardous incidents and critical infrastructure outages. Erdkunde 2018, 72, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- André, G.; Collins, S. Raising standards in emergency relief: How useful are Sphere minimum standards for humanitarian assistance? BMJ 2001, 323, 740–742. [Google Scholar]

- FMIG—Federal Ministry of the Interior of Germany. National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure Protection (CIP Strategy); FMIG—Federal Ministry of the Interior of Germany: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UN OCHA. Agenda for Humanity. Overview. Advancing the Agenda for Humanity. Agenda for Humanity Booklet; OCHA: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Bogardi, J.J. Hazards, risks and vulnerabilities in a changing environment: The unexpected onslaught on human security? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2004, 14, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Human Security in Theory and Practice. Application of the Human Security Concept and the United Nations Trust Fund for Human Security; Human Security Unit, Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations Trust Fund for Human Security: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Van Westen, C.; Van Asch, T.W.; Soeters, R. Landslide hazard and risk zonation—Why is it still so difficult? Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2006, 65, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; von Winterfeldt, D. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthq. Spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A place-based model for understanding community resilience. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FMIG. Protecting Critical Infrastructures—Risk and Crisis Management. A Guide for Companies and Government Authorities, 2nd ed.; Federal Ministry of the Interior of Germany: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, C. Risk Assessment And Critical Infrastructure Protection In Health Care Facilities: Reducing Social Vulnerability; German Federal Service of Interior: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E.Y.; Yue, J.; Lee, P.; Wang, S.S. Socio-Demographic predictors for urban community disaster health risk perception and household based preparedness in a Chinese urban city. PLoS Curr. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhein, S. Kapazitäten der Bevölkerung zur Bewältigung Eines Lang Anhaltenden Flächendeckenden Stromausfalles: Empirische Untersuchung für das Bezugsgebiet Deutschland; Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe: Bonn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Goersch, H.G.; Werner, U. Empirical Study on the Feasibility of Measures for Public Self-Protection Capability Enhancement: Empirische Untersuchung der Realisierbarkeit von Massnahmen zur Erhoehung der Selbstschutzfaehigkeit der Bevoelkerung; Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe: Bonn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heagele, T.N. Lack of evidence supporting the effectiveness of disaster supply kits. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohder, C.; Röpcke, J.; Sticher, B.; Geißler, S.; Schweer, B. Relief Needs and Willingness to Help in the Event of Long-Term Power Blackout. Results of a Citizen Survey in Three Berlin Districts; Berlin School of Economics and Law: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Birkmann, J.; Wenzel, F.; Greiving, S.; Garschagen, M.; Vallée, D.; Nowak, W.; Welle, T.; Fina, S.; Goris, A.; Rilling, B.; et al. Extreme events, critical infrastructures, human vulnerability and strategic planning: Emerging research issues. J. Extreme Events 2016, 3, 1650017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maxwell, D. Food security and its implications for political stability: A humanitarian perspective. In Proceedings of the FAO High Level Expert Forum on Addressing Food Insecurity in Protracted Crises (FAO, Rome), Rome, Italy, 13–14 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pothiawala, S. Food and shelter standards in humanitarian action. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 15, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Urlainis, A.; Shohet, I.M.; Levy, R.; Ornai, D.; Vilnay, O. Damage in critical infrastructures due to natural and man-made extreme events—A critical review. Procedia Eng. 2014, 85, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miles, S.B. Foundations of community disaster resilience: Well-Being, identity, services, and capitals. Environ. Hazards 2015, 14, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesnetzagentur. Untersuchungsbericht über die Versorgungsstörungen im Netzgebiet des RWE im Münsterland vom 25.11.2005; Bundesnetzagentur: Bonn, Germany, 2006; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Menski, U.; Gardeman, J. Auswirkungen des Ausfalls Kritischer Infrastrukturen auf den Ernährungssektor am Beispiel des Stromausfalls im Münsterland im Herbst 2005; FH Münster: Münster, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UCTE—Union for the Co-Ordination of Transmission of Electricity. Final Report System Disturbance on 4 November 2006; UCTE—Union for the Co-Ordination of Transmission of Electricity: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- DKKV. Lessons Learned. Hochwasservorsorge in Deutschland. Lernen aus der Katastrophe 2002 im Elbegebiet; DKKV 29; DKKV—Deutsches Komitee für Katastrophenvorsorge e.V.(German Committee for Disaster Reduction): Bonn, Germany, 2003; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- DKKV (Ed.) Das Hochwasser im Juni 2013. Bewährungsprobe für das Hochwasserrisikomanagement in Deutschland; DKKV-Schriftenreihe Nr. 53; DKKV e.V.: Bonn, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pescaroli, G.; Kelman, I. How Critical infrastructure orients international relief in cascading disasters. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 2017, 25, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dufour, C.; de Geoffroy, V.; Maury, H.; Grünewald, F. Rights, standards and quality in a complex humanitarian space: Is Sphere the right tool? Disasters 2004, 28, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, G. Dilemmas and challenges for the shelter sector: Lessons learned from the sphere revision process. Disasters 2004, 28, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, I.; Alexander, D. Recovery from Disaster; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 390. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L. Shelter strategies, humanitarian praxis and critical urban theory in post-crisis reconstruction. Disasters 2012, 36, S64–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, K.; Suvatne, M.; Kennedy, J.; Corsellis, T. Urban shelter and the limits of humanitarian action. Forced Migr. Rev. 2010, 34, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Interior of the State of North-Rhine Westfalia. Betreuungsdienst-Konzept NRW «Betreuungsplatz-Bereitschaft 500 NRW» (BTP-B 500 NRW); Ministry of the Interior of the State of North-Rhine Westfalia: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2009; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Garschagen, M.; Sandholz, S. The role of minimum supply and social vulnerability assessment for governing critical infrastructure failure: Current gaps and future agenda. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tzavella, K.; Fekete, A.; Fiedrich, F. Opportunities provided by geographic information systems and volunteered geographic information for a timely emergency response during flood events in Cologne, Germany. Nat. Hazards 2018, 91, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN/HABITAT. New Urban Agenda; United Nations, Habitat III Secretariat: Quito, Ecuador, 2017; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oers, R.; Roders, A.P. Aligning agendas for sustainable development in the post 2015 world. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.L.; Blanchard, M.K.; Maini, R.; Radu, A.; Eltinay, N.; Zaidi, Z.; Murray, V. Knowing what we know–Reflections on the development of technical guidance for loss data for the sendai framework for disaster risk reduction. PLoS Curr. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, V.; Maini, R.; Clarke, L.; Eltinay, N. Coherence between the Sendai framework, the SDGs, the climate agreement, new urban agenda and world humanitarian Summit, and the role of science in their implementation. In Proceedings of the Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction, Cancun, Mexico, 24–26 May 2017; pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner, B. Five years beyond Sendai—Can we get beyond frameworks? Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Nanda, T.P.; Singh, S.; Upadhyay, K.; Sawhney, A.; Swamy, D.R.R. Analysing the role of India’s smart cities mission in achieving sustainable development goal 11 and the new urban agenda. In Sustainable Development Research in the Asia-Pacific Region; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Mitlin, D. Finance for shelter: Recent history, future perspectives. Small Enterp. Dev. 2003, 14, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Rajan, A.T.; Jebaraj, P.; Elayaraja, M. Delivering basic infrastructure services to the urban poor: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of bottom-up approaches. Util. Policy 2017, 44, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, S.K.; Asadzadeh, A.; Kuusaana, E.D.; Mallick, B.; Koetter, T. Stakeholders participation for urban climate resilience: A case of informal settlements regularization in Khulna City, Bangladesh. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2015, 7, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdyke, A.; Lepropre, F.; Javernick-Will, A.; Koschmann, M. Inter-Organizational resource coordination in post-disaster infrastructure recovery. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javernick-Will, A. Motivating knowledge sharing in engineering and construction organizations: Power of social motivations. J. Manag. Eng. 2012, 28, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.F. Human Adjustment to Floods. A Geographical Approach to the Flood Problem in the United States; Research Paper No. 29; The University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Jochimsen, R. Theorie der Infrastrucktur: Grundlagen der Marktwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung; Mohr Siebeck: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laak, D. Der Begriff „Infrastruktur“ und was er vor seiner Erfindung besagte. Arch. Begr. 1999, 41, 280–299. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, P.N. Infrastructure and modernity: Force, time, and social organization in the history of sociotechnical systems. Mod. Technol. 2003, 1, 185–226. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, C.; Simon, G.L.; Roth, F.; Lakhina, S.J.; Wisner, B.; Adler, C.; Thomalla, F.; Scolobig, A.; Brady, K.; Bründl, M.; et al. Rethinking the interplay between affluence and vulnerability to aid climate change adaptive capacity. Clim. Chang. 2020, 162, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sectors Covered in the Sphere Handbook | Food and Nutrition | Health Services | Shelter | Water/WASH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Details | ||||

| Details provided on minimum standards | Food and calories | Percentages of healthcare services, inpatient bed numbers and walking distances, staff numbers, medicine, Early Warning and health information reporting | Minimum living space Minimum clothing, bedding, food and cooking facilities | Water containers of drinking water and water for everyday use, and soap consumption, personal hygiene, water volume and numbers of taps, water quality, toilets, healthcare settings for disease treatment, and differences of water needs for different facilities such as schools, mobile clinics, mosques |

| Missing aspects of ‘Critical Infrastructure’ | Food production and supply chains, logistics, food quality and variety | Unique services such as fire burn treatment, psychological support for elderly and children, etc. | Supporting infrastructure such as electricity, cooling and heating, accessibility, tele-/communication through mobile phone charging kits, etc. | Grid-based water supply, (waste)water discharge and treatment |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fekete, A.; Bross, L.; Krause, S.; Neisser, F.; Tzavella, K. Bridging Gaps in Minimum Humanitarian Standards and Shelter Planning by Critical Infrastructures. Sustainability 2021, 13, 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020849

Fekete A, Bross L, Krause S, Neisser F, Tzavella K. Bridging Gaps in Minimum Humanitarian Standards and Shelter Planning by Critical Infrastructures. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020849

Chicago/Turabian StyleFekete, Alexander, Lisa Bross, Steffen Krause, Florian Neisser, and Katerina Tzavella. 2021. "Bridging Gaps in Minimum Humanitarian Standards and Shelter Planning by Critical Infrastructures" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020849

APA StyleFekete, A., Bross, L., Krause, S., Neisser, F., & Tzavella, K. (2021). Bridging Gaps in Minimum Humanitarian Standards and Shelter Planning by Critical Infrastructures. Sustainability, 13(2), 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020849