1. Introduction

This study presents an environmental perspective in financial reporting regarding the disclosure of investments. The study fits into the broader context of the discussion on possible paths for measuring human impact on the environment. The COVID-19 stress tests accelerate the search for the potential digitalization of multi-dimensional communication [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] and promote a search for new paths for information digitalization and transformation.

Financial reporting is based on the model of aggregation of economic transactions in a double-entry system. It is probably the oldest arithmetic and business concept in economic practice, dating back to at least the 14th century [

9]. Hence, both the mechanism and the purpose of registration were narrowly defined. At the end of the 20th century, man’s economic activity upset the global balance of the ecosystem [

2], the effects of which we can now see with the naked eye. However, the foundation of measurement and reporting is still unchanged. Without information about the real impact of human beings on the environment, neither management, nor owners, nor political decision-makers, can make fully informed decisions [

3].

This study outlines the concept of a multi-purpose record as a mechanism for changing the financial reporting model to reflect the effects of human use of the environment. It also fills a gap in the discussion of integrated business reporting with a proposal to record environmental impacts at the level of individual transactions as opposed to the currently used synthetic indices or descriptive disclosures.

2. Overview of the Main Reporting Trends

Over the last thirty years, there have been eight developments in corporate financial reporting. First, the volume of financial statements is increasing. Standard compliance reporting systems (e.g., the case of Poland during the socialism period and thereafter) used a universal chart of accounts, and the aggregation of it was rigid. That is, it was constrained by financial regulations. Deviation from the rigid and universal concept of the chart of accounts resulted in the development of different types of accounting options within given standards. This contributed to the need to disclose accounting policies in financial reporting.

Second, the principles of financial reporting are being unified. While the United States’ Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (US GAAP) prevailed in the 1980s against the backdrop of dispersed national systems at the beginning of the 21st century, Europe adopted International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) reporting as its basis. This gives rise to two equivalent financial reporting systems and a slow reduction in the diversity of national systems and their convergence toward IFRS.

Third, to guarantee the universality of the IFRS in its design (unlike US GAAP), there is a conceptual framework: the equivalent of general principles in the legal system. The conceptual framework in IFRS is dynamic, and the standards are slowly becoming more detailed and interchanged (e.g., selective implementation by the European Commission and Council). As a result, IFRS is subject to conceptual inflation over time, and the quantity of firms converting to US GAAP [

10] is growing, causing a mirage of an instructional system via a conceptual system. This has resulted in the bloating of additional information and its descriptive nature.

Fourth, the complexity of business transactions is increasing [

11]. Financial instruments, the fair value concept, risk management, the prudential reporting model (now integrated into IFRS and US GAAP), and the risk concept of a set of transactions, as opposed to the risk of an individual transaction, are emerging. Moreover, financial reporting has not kept pace with changes in the global asset structure; the increasing value of entities is shaped by intangible assets (e.g., number of patents), development and research expenditure, relationship monetization, and brand and trademark value, with balance sheet aggregates of these items having low interpretative value.

Fifth, related party transactions, off-balance sheet and guarantee transactions, the arbitrariness of fair value measurements for inefficient markets, and the development of complex derivative financial instruments such as credit default swaps (CDS), contract for differences (CFDs), unit-link, and similar items are increasing in the same stream of business developments. In this context, both financial and managerial accounting failed to adhere to business reality. Haslam et al. [

12] point out that there is even contradiction in understanding management accounting by different types of stakeholders. Thus, the tendency to catch up with the growing gap is addressed through risk management and risk disclosure. For example, Durst et al. [

13] indicate that knowledge of risk management strengthens an entity’s competitive advantage. However, effective risk management stimulates the digitalization of the data.

Sixth, financial reporting is digitized. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (US SEC) first introduced an obligation for supervised entities to transmit data electronically to the supervisor. The turn of the century sees the implementation of eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) [

14,

15] as an electronic data-reporting standard. Europe is introducing such an obligation in 2020.

Seventh, under pressure from green shareholders (who incorporate the environmental criteria into the decision process), companies have started to publish environmental impact information as part of, or in parallel with, financial reporting. For the time being, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reporting is unstructured and does not necessarily meet the conditions for horizontal and vertical comparability between entities and within groups. CSR reporting is primarily a narrative complement to financial reporting, as it is currently not integrated at the level of recording individual economic events, although it is slowly being standardized [

16]. The CSR is claimed to be unstable [

17] and poorly integrated in financial reporting [

18] and weakly understood [

19].

Eighth, the combination of trends in the digitization of the general ledger, cloud transactions, and the standardization of reporting rules reduces transaction costs and tensions on the agent/master line. As a result, the current financial audit is moving away from records to operational consulting.

In IFRS design, unlike US GAAP, there is a conceptual framework that is the equivalent of general principles in the legal system [

20]. The conceptual framework in the IFRS is dynamic, and the standards are slowly becoming more detailed and interchanged (e.g., selective implementation by the European Commission and the council). As a result, IFRS is subject to conceptual inflation over time, and the volume converting to US GAAP is growing [

21]. This has resulted in the bloating of additional information and its descriptive nature, which opens space for misuse, e.g., covering up unfavorable information [

22].

The related party transactions, off-balance sheet, and guarantee transactions, arbitrariness of fair value measurements for inefficient markets, and the development of complex derivative financial instruments such as CDSn, CFDs, unit-link, and the like are increasing in the same stream of business developments. Financial reporting addresses those changes mainly through narratives and has failed to account for value creation changes from tangible assets to intangible [

23].

Despite the relatively intensive development of financial reporting, the foundation on which it is based, namely the accounting system, has not changed for centuries. The solution offered by practice boils down to increasing the volume of financial statements through an excessive unstructured description of test transaction characteristics. The user of financial statements receives an excessive amount of information and, combined with natural cognitive constraints, cannot rationally process, aggregate, and compare the information. This situation results in a tendency to make increasing use of machine analysis (e.g., text mining) [

24] that is burdened with a large error in the analytical model itself. Despite the practical application of advanced tools for data analysis and aggregation, information about the environmental impact of business units is lost based on the system. Therefore, this study identifies a research gap consisting of the fact that the currently used double-entry system only transfers information about the transactions’ economic value (the verification of the research gap presents the

Appendix A). Having identified the research gap, let us review the current European legal framework for integrated reporting.

3. European Legal Background of the Integrated Reporting Implementation

The need to adopt certain elements of integrated reporting was recognized by the European Union. Amendment to the directive on the annual and consolidated financial statements and related reports (Directive 2013/34) introduced obligations concerning disclosing certain non-financial and diversity information (Directive 2014/95). Non-financial statements should be included in the management report or a separate report. Directive 2014/95 defines the minimum content of the non-financial statements, which includes, inter alia, environmental, social, and employee matters [

25]. It is hard to make a conclusive assessment of the adopted solutions [

26], particularly while taking into account a broader perspective on global development to the integrated reporting concept [

27,

28].

On the one hand, in some Member States, there was an obligation to disclose non-financial reports (e.g., the UK, Sweden, Spain, Denmark, and France) and undertakings often published reports on their initiative to present their business as socially responsible [

29]. The European Commission’s analysis showed that the information disclosed in non-financial reports was often lacking in materiality or was not sufficiently balanced, accurate, and timely [

30]. Hence, there was a need to establish a certain minimum legal requirement in the directive and make non-financial reports available to the public.

On the other hand, the EU’s harmonization scope is very limited and leaves a wide margin of discretion for the Member States [

31]. First, this concerns a small population of undertakings that should apply regulations (around 6000 large companies and groups across the EU [

32] and in Poland approximately 300 [

33]). The obligation to disclose is only applicable to certain large undertakings that are public-interest entities.

Second, Directive 2014/95 does not specify the material scope of obligations and gives companies significant flexibility to disclose relevant information (reporting on a “comply or explain” basis). The Commission’s guidelines on the methodology for reporting non-financial information do not solve the problem because they are also at a high level of generality. Complaints concern an international (United Nations Global Compact) or national set of guidelines (based on ISO 26000 Social Responsibility).

Third, there is no legal obligation regarding auditing reports and directives limited to checking by the statutory auditor regarding whether the non-financial statements have been provided. Stakeholders should be certain that non-financial reports give an accurate and fair view of the company’s financial position. This aim could be achieved only during an audit that is compliant with the auditing defined standards.

Finally, costs incurred in relation to the drafting and publication of a report and specific staff training or data collection costs may vary depending on the scope and content and a possible review. According to the European Commission’s calculations, the disclosure cost was estimated to be between € 600 and € 4300, typically requiring about two working weeks-time per year per company, thus generating a total cost between 10.5 and 75.25 million euros [

30]. The commission has looked into the alternative of considering the costs of full mandatory reporting, and those costs were estimated in a range varying between € 33,000 and € 604,000 per year per company, depending on the company’s size and complexity, including verification costs [

34], p. 83. Actual costs incurred by the concerned undertakings were at the level of € 100,865 per annum where the lowest cost was to apply the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Guidelines for Multinational enterprises (€ 1096 per annum) and the highest cost was to apply the Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (€ 493,000 per annum)[

35], p. 22.

The range of integration within European Union law and implementation of the Directive 2014/95 is broad. Full integration would be too expensive for undertakings, but implemented limited integration has failed to meet the hopes placed upon it—even if, in 2019, the European Commission began to discuss the possible revision of Directive 95/2014/EU [

31]. This paper offers a contrary solution, namely to integrate financial and environmental transaction recording.

4. Model Concept

The proposed solution is to introduce, instead of a double record of transactions (Dr.-Cr.) with one value, multiple records, where one transaction is recorded by the system as two double records with two different values. This system would contain two records, the first being the classic one known from the recording of economic events in Dr.-Cr., and the second part of the record would be the environmental impact of the transaction in the form of the SDr.-SCr. [

36] record. Consequently, one transaction would be described by at least four technical records with at least two values of the first being financial, and the second environmental.

The model would inherit all the features of the existing financial model, but it would be different in size. That is, instead of indicating a single value (for business accounting purposes), it would indicate the value of the cost (or profit) of such a transaction for the human environment. By adding a second dimension, we complement the financial information with environmental impacts at each economic transaction level, allowing this system to inherit all aggregates used from accounting equipment, such as financial statements, taxes, public statistics, and particularly gross domestic product [

37], national accounts, etc. This results in the transfer of aggregated information for the decision-maker at any organizational level, from the operational manager through to management, owner, state, and local government bodies to the national and international level.

5. Illustration of the Model Using the Example of Investment Disclosures

Within the conceptual model, environmental transactions are allowed, which transfer environmental value without affecting financial transactions. The proposed concept is difficult to verify with classic methods because there is no productive implementation. Therefore, until the concept is put into practice, it can be illustrated either by simulation or by an illustrative example. The simulation issue has been singled out for another study, including an illustrative example of the proposed concept.

Let us assume that (1) a system of multiple recording of financial and environmental values is used, (2) all values are aggregated according to the applied financial reporting standard, (3) all transactions are measured reliably, and (4) their financial and environmental value can be clearly shown at the transaction level. For illustrative purposes, environmental aggregated values are assumed arbitrarily, as the log and general ledger aggregation follow. With these assumptions, it is possible to illustrate what disclosure would look like, with and without environmental data. For this purpose, we will use the 2019 consolidated accounts of the Orlen Capital Group for “Investments in equity valuation” (see

Table 1 bellow).

Existing disclosure does not allow for the determination of how the joint venture expenses affect the environment. Using multiple disclosures, a two-dimensional value space can be obtained.

Table 2 shows the effect of extending the system to environmental value. Column F indicates the financial values over the period, and Column S indicates the environmental values (ecological footprint).

Table 2 shows the aggregated environmental impact of the Basel investment and, in this case, it is negative. With this financial reporting structure, both the manager and the owner can directly assess the environmental impact of the business activity.

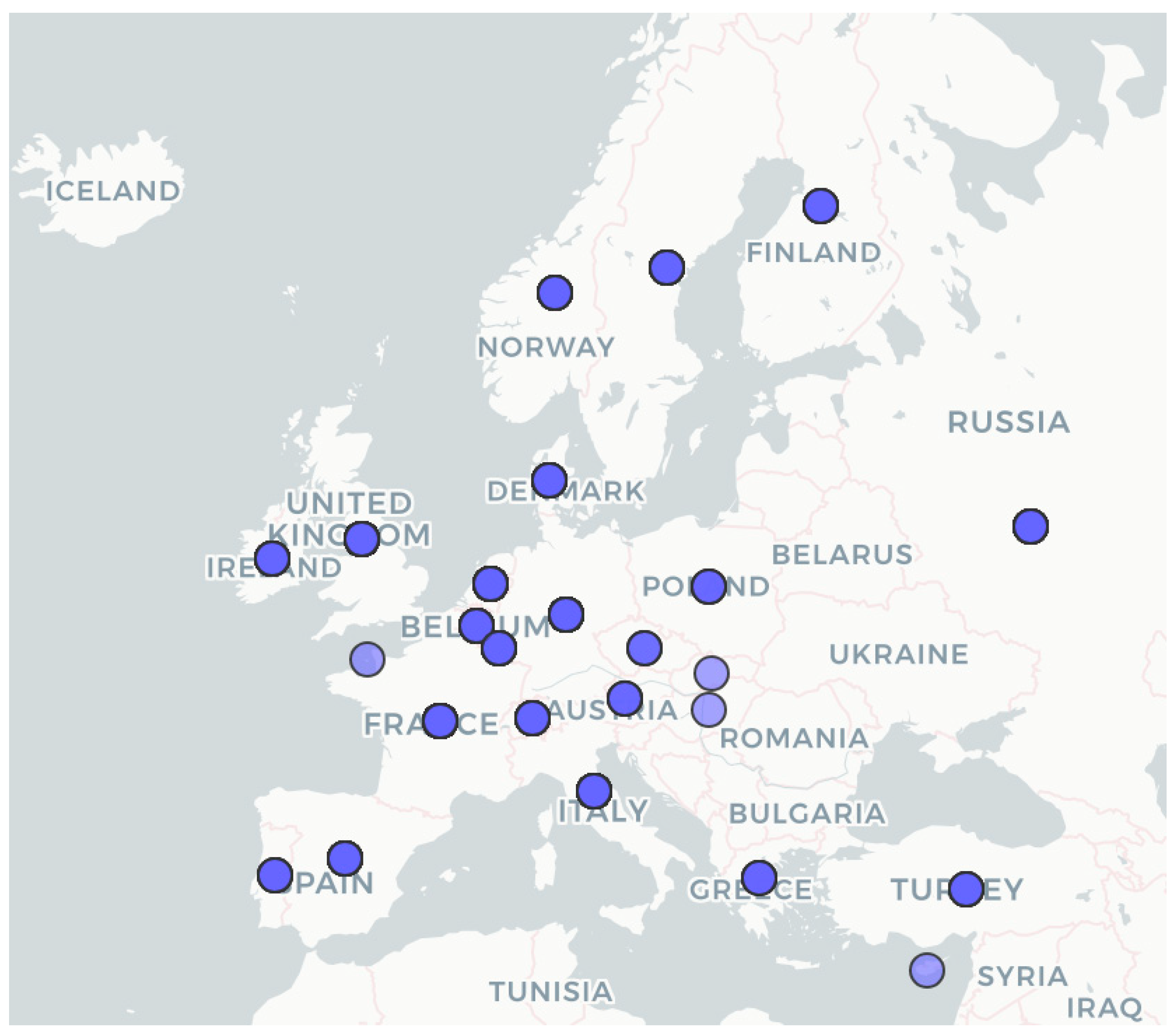

The illustration leads us to the more operational issue, namely, to the extent that environmental impact might enhance our understanding of corporate investments and environmental usage. To center our attention, consider the geographical and investment aspects—that is, if the investment value is equally distributed among countries and environmental footprints. Thus, the issue brings us to the following verifiable working hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The environmental footprint of investments follows the economic value distribution that allows for the testing of the extension of financial recording with environmental entries.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The environmental footprint of the investment is equally spread across European countries.

In turn, the H2 hypothesis allows us to verify the spatial effect of the recording extension.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper proposes a change in the way business transactions are recorded. The current double-entry system is replaced with a multi-entry system. The key difference is in a mutual recording of both financial and environmental values in two charts of accounts. The multi-entry system provides assurance of linking both financial aspects and environmental values at the transaction level. It results in the possibility to produce multi-dimensional integrated reporting. As a consequence, the multi-entry system needs less descriptive and narrative notes for the reporting. Consequently, the reporting comes back to its roots and presents aggregated data in a consistent way. This attribute allows the multi-entry system to contribute to the solution of mutual reporting of corporate financial and environmental impact.

The key findings from the simulation are that the EF is a significant variable to discriminate the geographical allocation. Thus, the actual modeling of the sustainable impact of business on the transaction level leads to enhancement of the information value transferred by the business entities to the stakeholders, mainly society. The enhanced journal entry model in its simplicity is elegant and, probably, unlike the triple entry model [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49], it can be applied in practice by simply extending the journal entry posting instructions of an accounting document (both in manual and electronic systems). In contrast to recording the costs of using the environment only as transactions with sovereignty (receivable/payable for the use of the environment by an entity), it provides stakeholders with atomized information on the entity’s environmental impact. Since it inherits the structure of financial information, classical financial analysis tools can be adapted to environmental analysis (e.g., break-even point for the environment), human resources disclosure [

50], insolvency prediction [

51], even to such a remote area as the efficiency of the law’s impact on a business (for an extended discussion of the efficiency aspects, refer to the outline offered by Kozhokar [

52]). The model is probably also suitable for the supplementary disclosure of the human resource aspects, as analyzed by Bulut Sürdü et al. [

50]. Further research is needed in the context of the valuation basis. On the other hand, the implementation of the model would require an incremental effort from the side of education, as Cernostana [

53] already identified as one of the model’s limitations.

The practical application of the proposed concept is limited by the legal system. As financial reporting rules have the characteristics of a legal standard, it is impossible to apply this concept until the law is changed. Therefore, the proposed concept may develop in the field of management accounting, because in this system, the decision to apply environmental reporting is made by the stakeholders.

The proposal assumes the reliability, coherence, and measurability of environmental transactions. These are quite strong constraints, and, therefore, an environmental and financial review mechanism should be included to avoid excessive transaction costs. Some friction might occur in terms of auditing for integrated reporting and governance structure (see Dobija [

54] for an examination of the relationship between audit committees and auditor interaction). However, the potential consequences for auditing require an isolated study. The paper does not compare the triple-entry and multi-entry systems, specifically in terms of the current XBRL and blockchain developments [

55]. It is probable that an extended study in this direction might enhance our knowledge.

The application of the proposed solution in practice requires detailed research. The feasibility of valuing the environmental impact at the level of an individual transaction is an open question, and the classification of transactions and the way they are valued also require separate studies.

This study presents a preliminary and rather conceptual outline of the idea, but the solutions proposed may serve social policymakers to manage environmental resources more consciously and responsibly.