Socio-Economic Factors Influencing Travel Decision-Making of Poles and Nepalis during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

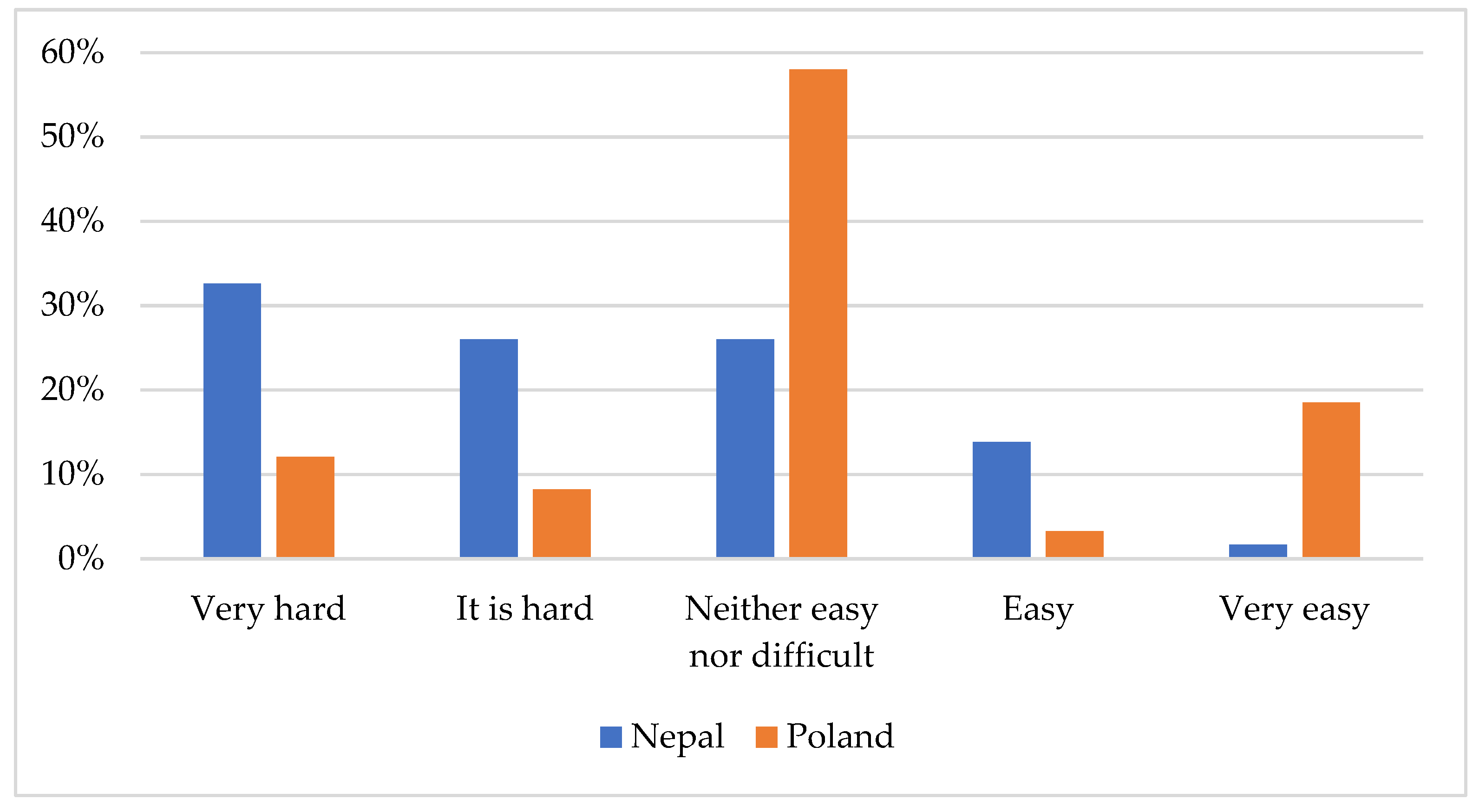

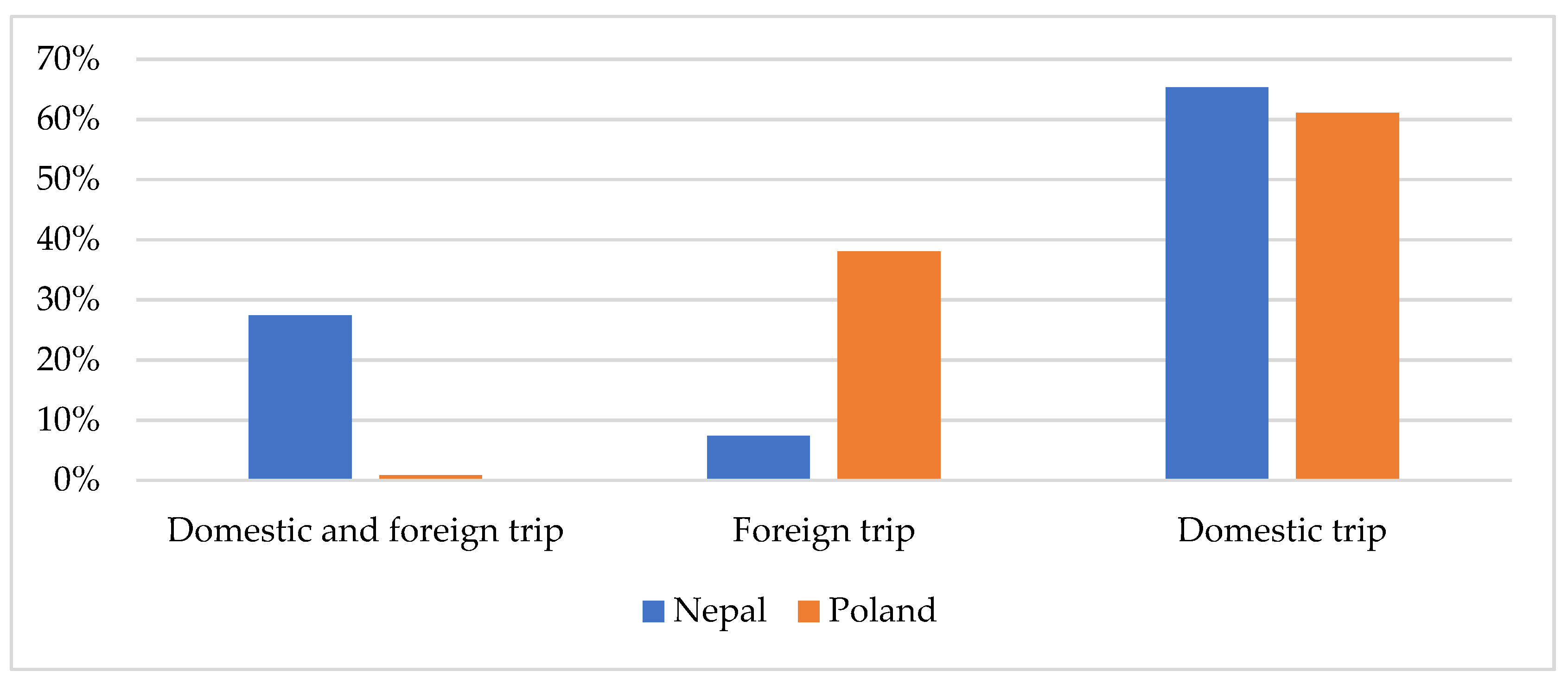

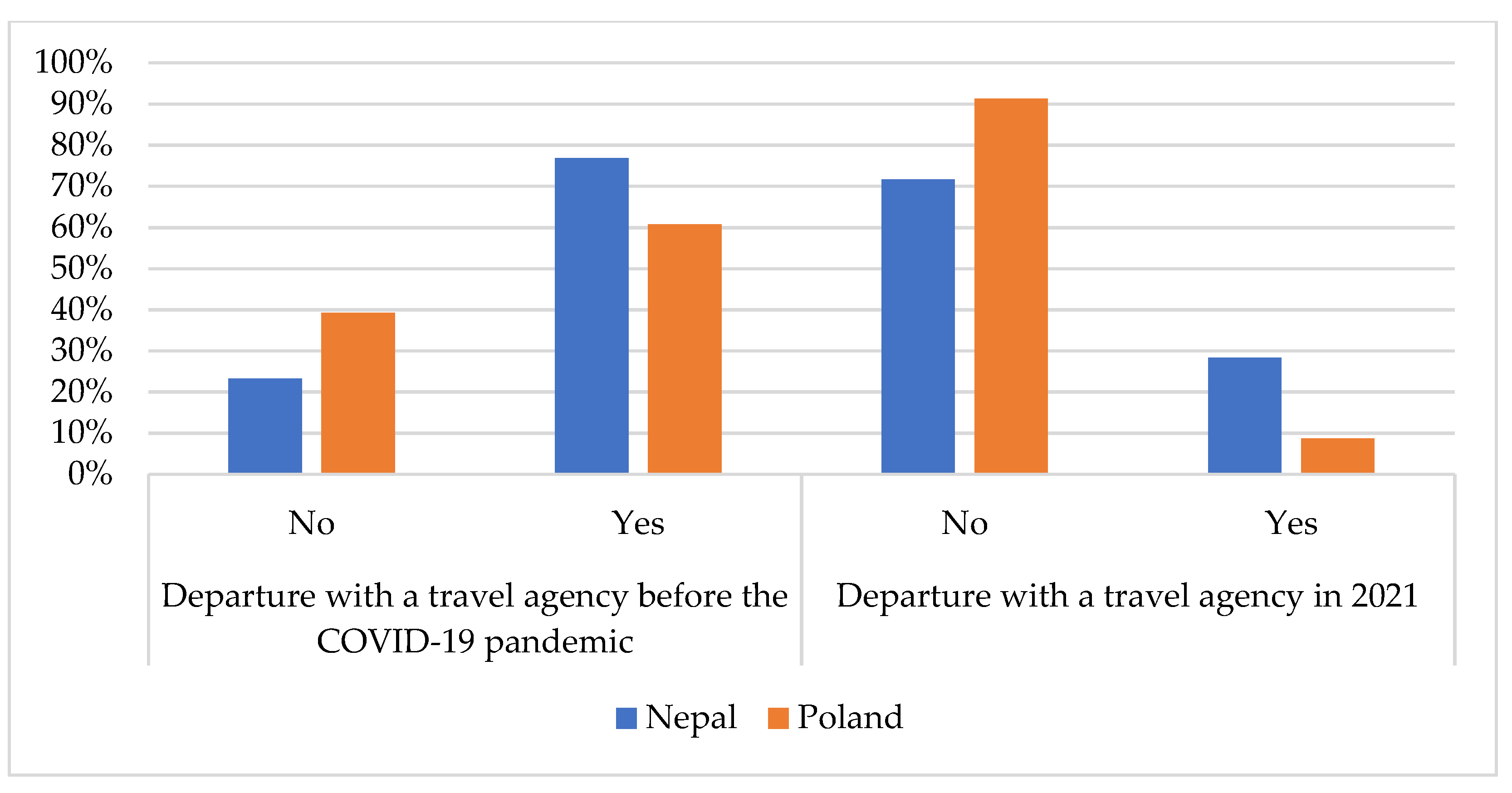

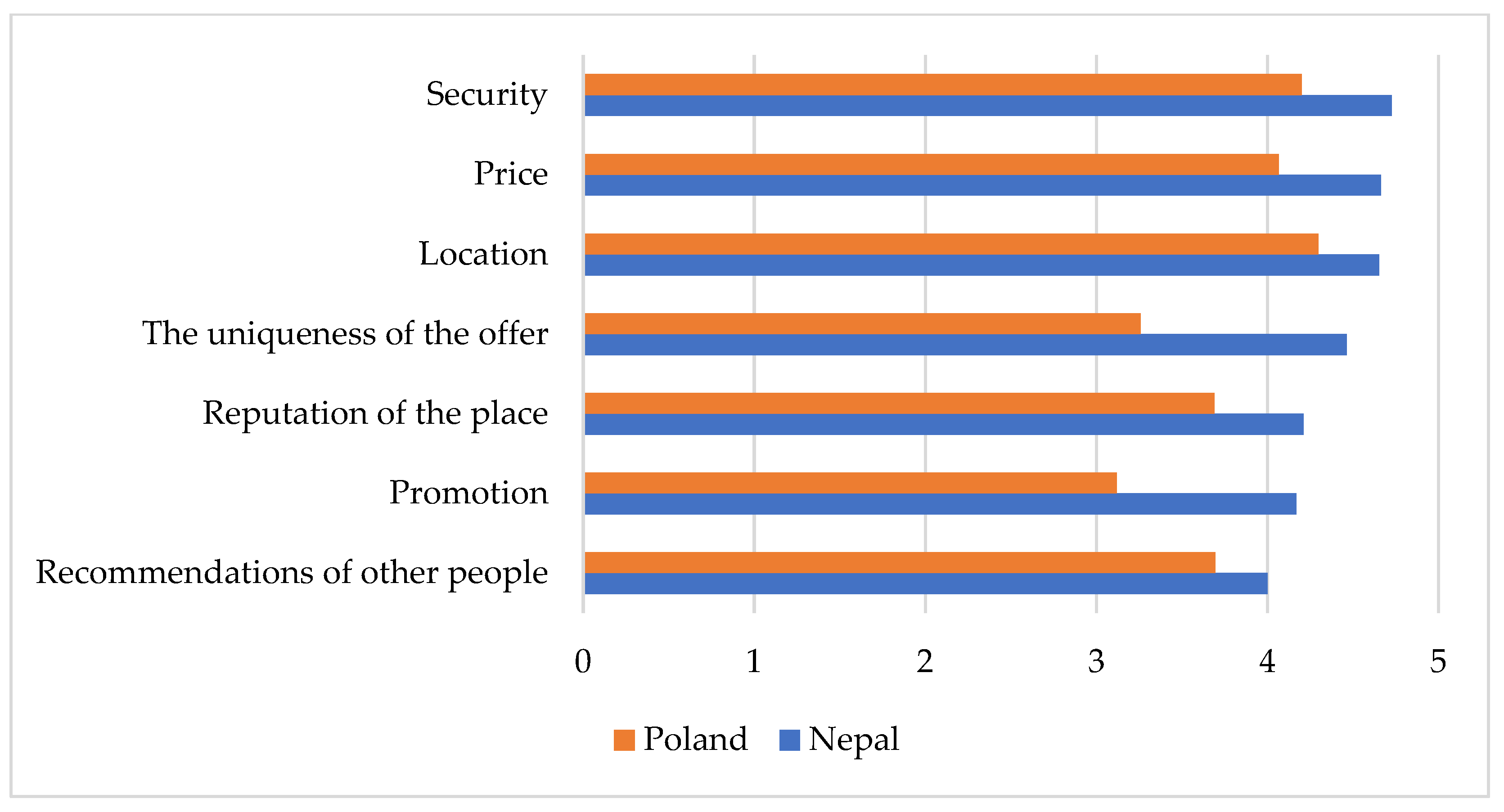

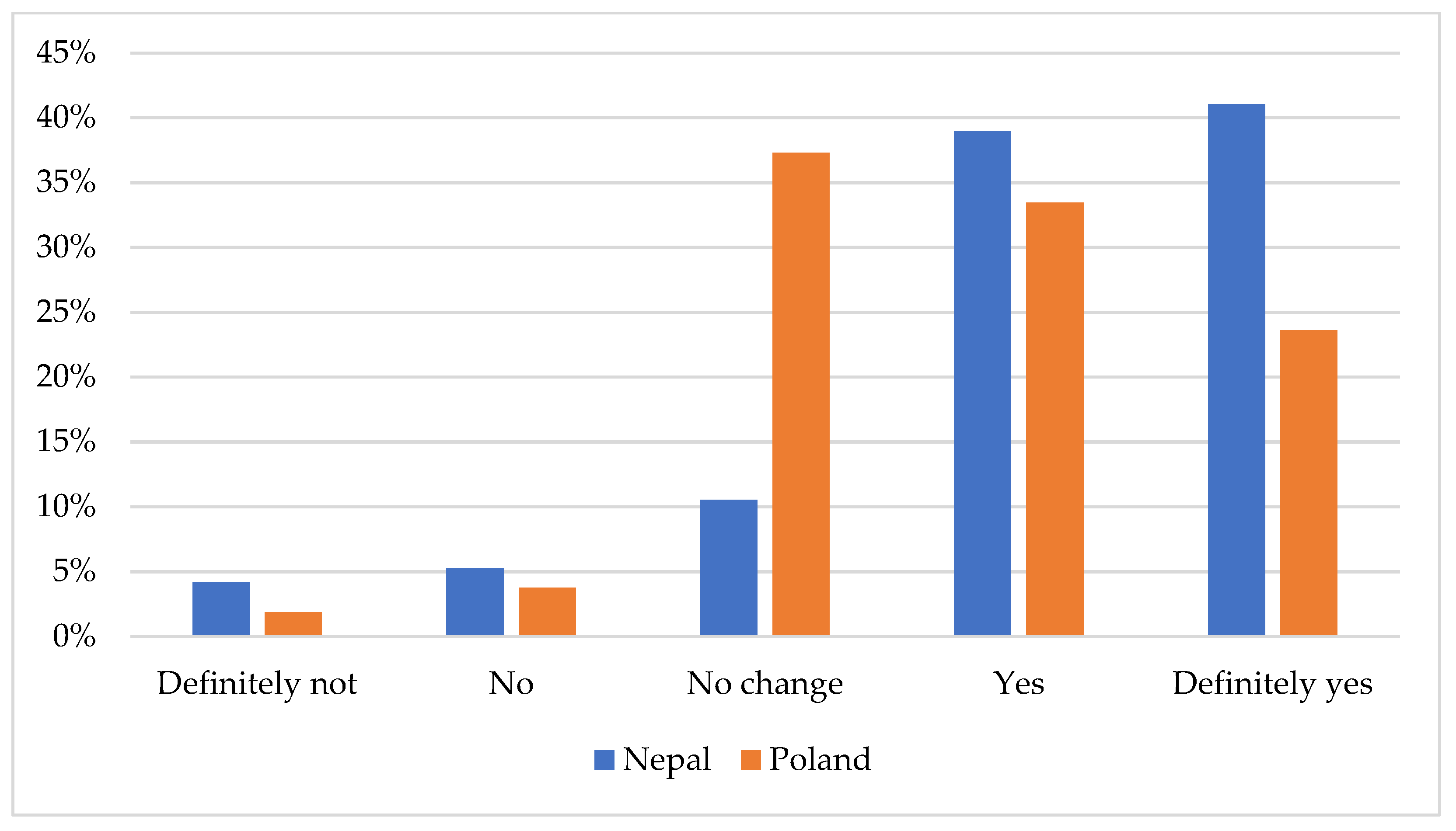

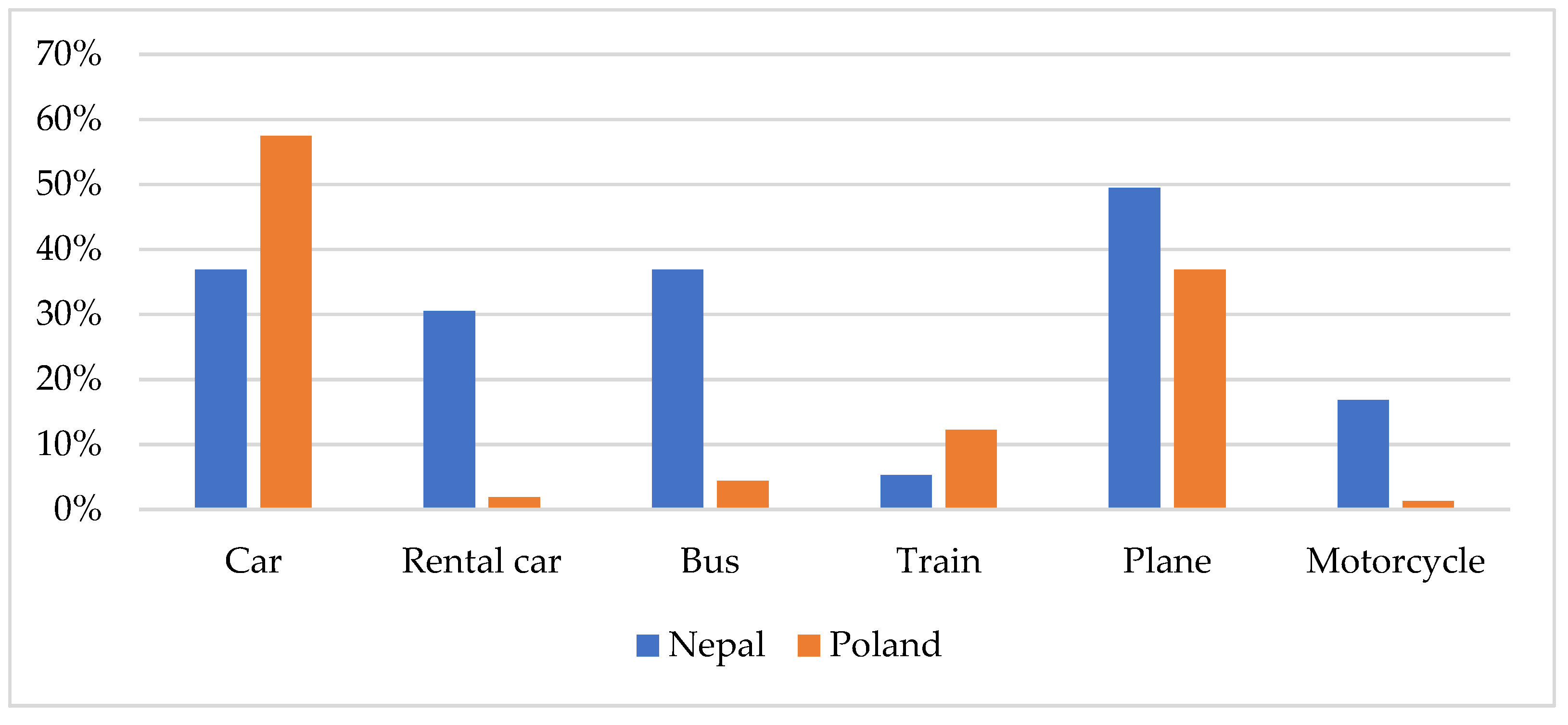

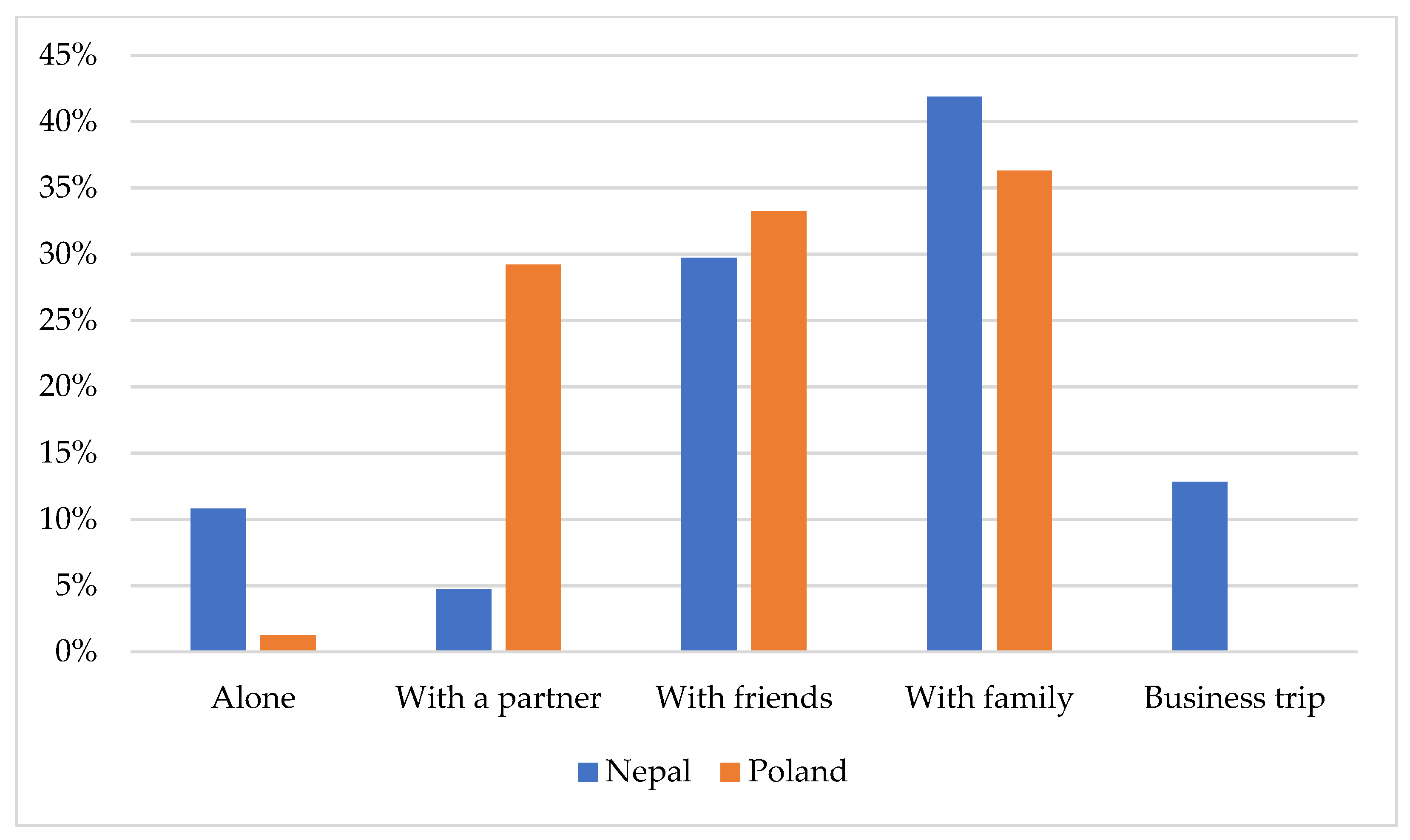

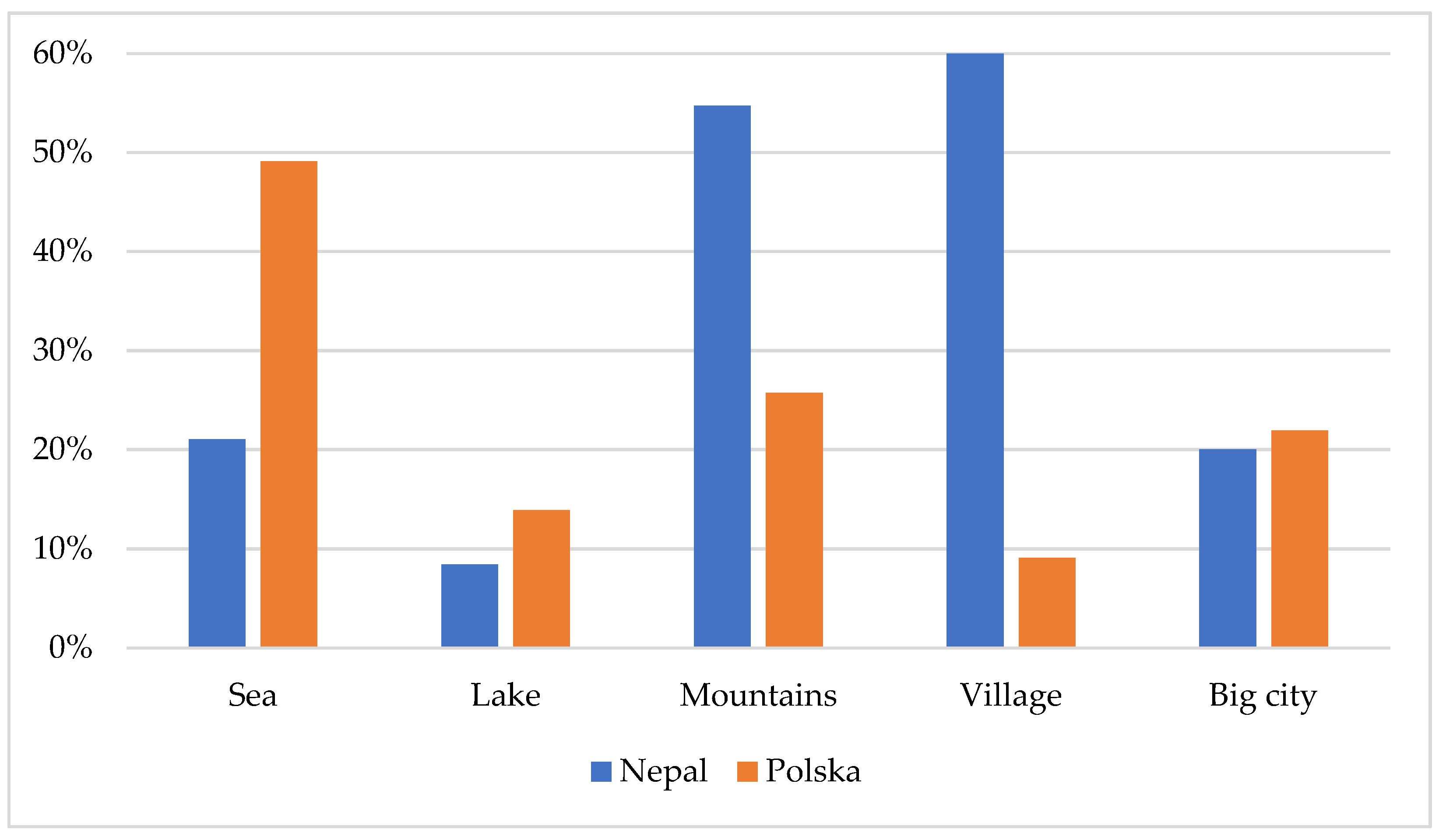

4. Results

5. Discussions and Conclusions

- What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism labor market?

- Will the COVID-19 virus lead to a radical transformation of the tourism sector?

- How might the tourism and hospitality industries respond to such changes in the future?

- How can we mitigate similar future public health crises?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak Situation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Correa-Martínez, C.L.; Kampmeier, S.; Kümpers, P.; Schwierzeck, V.; Hennies, M.; Hafezi, W.; Kühn, J.; Pavenstädt, H.; Ludwig, S.; Mellmann, A. A pandemic in times of global tourism: Superspreading and Exportation of COVID-19 cases from a ski area in Austria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.pl/wiadomosci/koronawirus-w-polsce-i-na-swiecie-aktualna-mapa-zachorowan-ilu-jest-chorych-ile-osob/yl0meqc (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- UNWTO. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-covid-19 (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Al Jazeera Coronavirus: Travel Restrictions, Border Shutdowns by Country. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/coronavirus-travel-restrictions-border-shutdowns-country-200318091505922.html (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Richter, L.K. International tourism and its global public health consequences. J. Travel Res. 2003, 41, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilsenrath, J. Global viral outbreaks like coronavirus, once rare, will become more common. The Wall Street Journal, 6 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sheresheva, M.; Efremova, M.; Valitova, L.; Polukhina, A.; Laptev, G. Russian tourism enterprises’ marketing innovations to meet the COVID-19 challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halme, M. Learning for sustainable development in tourism networks. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism and sustainable development exploring the theoretical divide. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Niedziółka, A.; Krasnodębski, A. Respondents’ involvement in tourist activities at the time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M.; Muskat, B.; Ritchie, B.W. Which travel risks are more salient for destination choice? An examination of the tourist’s decision-making process. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y. The potential of virtual tourism in the recovery of tourism industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallman, C.; Moore, K. Process studies of tourists’ decision-making. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 37, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğur, N.G.; Akbıyık, A. Impacts of COVID-19 on global tourism industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; He, J.; Zhou, J. Communication related health crisis on social media: A case of COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 46, 2699–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westcott, B.; Wang, S. China is Experiencing a Rural Tourism Boom Amid the Covid-19 Pandemic; CNN: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nilashi, M.; Asadi, S.; Minaei-Bidgoli, B.; Ali Abumalloh, R.; Samad, S.; Ghabban, F.; Ahani, A. Recommendation agents and information sharing through social media for coronavirus outbreak. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 61, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.J.; Koo, C. The influence of tourism website on tourists’ behavior to determine destination selection: A case study of creative economy in Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 96, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Coronavirus impacts on post-pandemic planned travel behaviours. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 86, 102964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Goh, E.; Wen, J. The effects of misleading media reports about COVID-19 on Chinese tourists’ mental health: A perspective article. Anatolia 2020, 31, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, S.; Han, L.; Liu, P.; Zheng, Z.J. Global health governance for travel health: Lessons learned from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreaks in large cruise ships. Glob. Health J. 2020, 4, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforiadis, A.; Ayfantopoulou, G.; Stamelou, A. Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on bike-sharing usage: The case of Thessaloniki, Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulú, I.; Razumova, M.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. Can domestic tourism relieve the COVID-19 tourist industry crisis? The case of Spain. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100568. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.; Dias, C.; Muley, D.; Shahin, M. Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on travel behavior and mode preferences. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 8, 100255. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Z. Tourists on shared bikes: Can bike-sharing boost attraction demand? Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Xu, W.; Lee, J.; Lee, C.K.; Woosnam, K.M. Residents’ perceived risk, emotional solidarity, and support for tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100553. [Google Scholar]

- Anwari, N.; Tawkir Ahmed, M.; Rakibul Islam, M.; Hadiuzzaman, M.; Amin, S. Exploring the travel behavior changes caused by the COVID-19 crisis: A case study for a developing country. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100334. [Google Scholar]

- Polukhina, A.; Sheresheva, M.; Efremova, M.; Suranova, O.; Agalakova, O.; Antonov-Ovseenko, A. The concept of sustainable rural tourism development in the face of COVID-19 crisis: Evidence from Russia. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, L.F.; Plucinski, M.M.; Marston, B.J.; Kurbatova, E.V.; Knust, B.; Murray, E.L.; Pesik, N.; Rose, D.; Fitter, D.; Kobayashi, M.; et al. Public health responses to COVID-19 outbreaks on cruise ships—worldwide, February–March 2020. In MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad-Núñez, S.; Julio, R.; Gomez, J.; Moya-Gómez, B.; González, J.S. Post-COVID-19 travel behaviour patterns: Impact on the willingness to pay of users of public transport and shared mobility services in Spain. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankomah, P.K.; Crompton, J.L.; Baker, D. Influence of cognitive distance in vacation choice. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangrum, D.; Niekamp, P. JUE Insight: College student travel contributed to local COVID-19 spread. J. Urban Econ. 2020, in press, 103311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyadi, H.S.; Newsome, D. The post COVID-19 tourism dilemma for geoparks in Indonesia. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2021, 9, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.R.; Wu, D.C.; Drospy, V.; Petit, S.; Pratt, S.; Ohe, Y. Visitors arrivals forecasts amid COVID-19: A perspective from the Asia and Pacific Team. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, V.; Srivastava, S. Hospitality and tourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Boğan, E. The motivations of visiting upscale restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of risk perception and trust in government. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruman, J.A.; Chhinzer, N.; Smith, G.W. An exploratory study of the level of disaster preparedness in the Canadian hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011, 12, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Ritchie, B.W.; Walters, G. Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: A narrative review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.E.; Elbaz, A.M.; Elkhwesky, Z.; Ghazi, K.M. The COVID-19 pandemic: The mitigating role of government and hotel support of hotel employees in Egypt. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. UNWTO World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex. UNWTO World Tour. Barom. 2021, 19, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kizys, R.; Tzouvanas, P.; Donadelli, M. From COVID-19 herd immunity to investor herding in international stock markets: The role of government and regulatory restrictions. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 74, 101663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinfeng, L.; Guo, X. COVID-19 contact-tracing apps: A survey on the global deployment and challenges. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.03599. [Google Scholar]

- Mach, L.; Ponting, J. Establishing a pre-COVID-19 baseline for surf tourism: Trip expenditure and attitudes, behaviors and willingness to pay for sustainability. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2021, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Grudzień, P. The essence of agritourism and its profitability during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Agriculture 2021, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, K.; Ohe, Y.; Ciani, A. Which human resources are important for turning agritourism potential into reality? SWOT analysis in rural Nepal. Agriculture 2020, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan-Martin, N.C.; Madad, S.; Alves, L.; Wang, J.; O’Gere, L.; Smith, Y.G.; Pressman, M.; Shure, J.A.; Cosmi, M. Isolation hotels: A community-based intervention to mitigate the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Secur. 2020, 18, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K.W.; Wong, J.W.C. Comparing crisis management practices in the hotel industry between initial and pandemic stages of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3135–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T.; Hai, N.T.T. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sio-Chong, U.; So, Y.C. The impacts of financial and non-financial crises on tourism: Evidence from Macao and Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100628. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, H. Chinese public attention to COVID-19 epidemic: Based on social media: Observational descriptive study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Main Topic | Sub-Topics | Key Words | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information/promotion | Travel motivators | Health crisis, social media, online reviews (eWOM), DMOs, media sensations | Uğur and Akbıyık (2020) [16], Yu et al. (2020) [17], Westcott et al. (2021) [18] Nilashi et al. (2021) [19], Chung et al. (2015) [20], Junxiong et al. (2021) [21], Zheng et al. (2020) [22] |

| Travel behavior | Decision-making | Travel decision process, planning, and cancelation | Uğur and Akbıyık (2020) [16], Smallman and Moore (2010) [15], Karl et al. (2020) [13], Zhou et al. (2020) [23], Nikiforiadis (2020) [24], Wen et al. (2021) [25] |

| Travel motivation | Intentions to travel, travel experiences, consensus | Smallman and Moore (2010) [15], Roman et al. (2020) [12], Karl et al. (2020) [13], Arbulú et al. (2021) [26], Abdullah et al. (2020) [27], Yang et al. (2021) [28], Zhou et al. (2020) [23], Wen et al. (2021) [23,25], Zheng et al. (2020) [22], Sönmez and Graefe (1998) [29], Joo et al. (2021) [30] | |

| Transportation | Modes of transport, travel distance, alternative means of transport | Roman et al. (2020) [12], Anwari et al. (2021) [31], Abdullah et al. (2020) [27], Yang et al. (2021) [28], Polukhina et al. (2021) [32], Moriarty et al. (2020) [33], Zhou et al. (2020) [23], Nikiforiadis (2020) [24], Wen et al. (2021) [25], Awad-Núñez et al. (2021) [34] | |

| Destination selection | Travel decision, crisis, destination selection, tourism activities | Roman et al. (2020) [18], Polukhina et al. (2021) Ankomah et al. (1996) [35], Arbulú et al. (2021) [26], Mangrum and Niekamp (2020) [36], Cahyadi and Newsome (2021) [37] | |

| Safety and security | Risk | Crisis situation, perceived risk | Yu et al. (2020) [17], Karl et al. (2020) [13], Arbulú et al. (2021) [26], Sönmez and Graefe (1998) [29], Joo et al. (2021) [30] |

| Impact of COVID-19 | Tourism and hospitality, projection | Gössling et al. (2021) [9], Qiu et al. (2021) [38] | |

| Safety measures | Hygiene and sanitation, smartphone apps, health protocols | Junxiong et al. (2021) [21], Awad-Núñez et al. (2021) [34], Kaushal and Srivastava (2021) [39], Dedeoğlu and Boğan (2021) [40], | |

| Cooperation strategies | Disaster mitigation | Quarantine and post-pandemic strategies, tourism, and hospitality industry | Dedeoğlu and Boğan (2021) [40], Gruman et al. (2011) [41], Mair et al. (2016) [42] |

| HR | Government subsidy, external support, HR development, staff commitments | Salem et al. (2021) [43] Kaushal and Srivastava (2021) [39], Dedeoğlu and Boğan (2021) [40], Cahyadi and Newsome (2021) [37] |

| Specification | Poland (%) | Nepal (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 66.2 | 24.3 |

| Male | 33.8 | 75.7 | |

| Age (years) | <19 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| 20–29 | 60.9 | 50.8 | |

| 30–39 | 10.1 | 29.8 | |

| 40–49 | 21.7 | 12.2 | |

| ≥50 | 6.7 | 6.1 | |

| Education level | Secondary | 3.1 | 5.0 |

| High school | 36.4 | 21.0 | |

| Bachelor’s | 8.2 | 44.7 | |

| ≥Master’s | 52.4 | 29.3 | |

| Employment status | Retired pensioner | 2.0 | 2.8 |

| Manual worker | 3.4 | 1.1 | |

| Professional worker | 42.7 | 35.9 | |

| Student | 47.4 | 22.1 | |

| Business owner | 3.8 | 13.3 | |

| Unemployed | 0.7 | 4.4 | |

| Others | 0.0 | 20.4 | |

| Income of one family member | <PLN 1000/NPR 15,000 | 4.7 | 35.4 |

| PLN 1001–PLN 1500/NPR 15,001–NPR 25,000 | 14.1 | 13.8 | |

| PLN 1501–PLN 2500/NPR 25,001–NPR 35,000 | 31.3 | 9.9 | |

| PLN 2501–PLN 3500/NPR 35,001–NPR 45,000 | 20.2 | 7.2 | |

| >PLN 3500/NPR 45,001 | 29.7 | 33.7 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roman, M.; Bhatta, K.; Roman, M.; Gautam, P. Socio-Economic Factors Influencing Travel Decision-Making of Poles and Nepalis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011468

Roman M, Bhatta K, Roman M, Gautam P. Socio-Economic Factors Influencing Travel Decision-Making of Poles and Nepalis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2021; 13(20):11468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011468

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoman, Michał, Kumar Bhatta, Monika Roman, and Prakash Gautam. 2021. "Socio-Economic Factors Influencing Travel Decision-Making of Poles and Nepalis during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 13, no. 20: 11468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011468