Coastal Cities Seen from Loyalty and Their Tourist Motivations: A Study in Lima, Peru

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivations in Coastal Cities

2.2. Loyalty in Coastal Destinations

3. Methodology

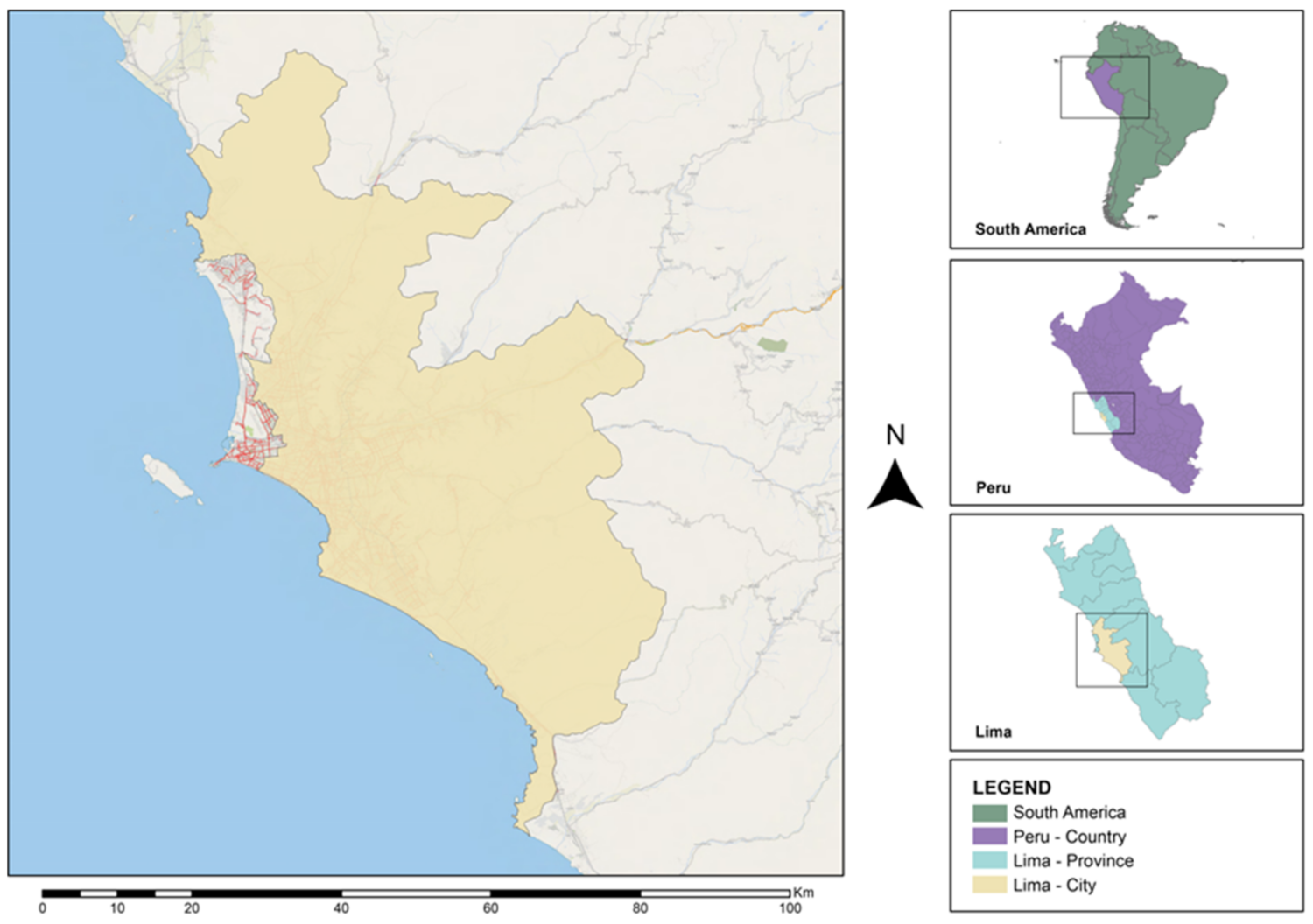

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Instrument, Collection of Data and Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.3. Relationship between Motivations and Return Intentions

4.4. Relationship of Motivations with the Intentions to Recommend

4.5. Relationship of Motivations with Saying Positive Things about the Destination

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crompton, J.L.; McKay, S.L. Motives of visitors attending festival events. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.K.; Horridge, P.E. Travel motivations as souvenir purchase indicators. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmann, P.; Skeete, R.; Waite, R.; Bangwayo-Skeete, P.; Casey, J.; Oxenford, H.A.; Gill, D.A. Coastal and marine quality and tourists’ stated intention to return to Barbados. Water J. 2019, 11, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Tourism Organization UNWTO. 2020: The Worst Year in the History of Tourism, with Billion Less International Arrivals. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/news/2020-el-peor-anode-la-historia-del-turismo-con-mil-millones-menos-de-llegadas-internacionales (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Dwyer, L. Emerging ocean industries: Implications for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2018, 13, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Hernández-Lara, A.B.; Buele, C.V. Segmentation, motivation, and sociodemographic aspects of tourist demand in a coastal marine destination: A case study in Manta (Ecuador). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1234–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orams, M.; Lueck, M. Coastal tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 157–158. [Google Scholar]

- Orams, M.; Lueck, M. Marine tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 585–586. [Google Scholar]

- Diakomihalis, M.N. Chapter 13 Greek Maritime Tourism: Evolution, Structures and Prospects. Res. Transp. Econ. 2007, 21, 419–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey, M.; Krantz, D. Global Trends in Coastal Tourism; Center on Ecotourism and Sustainable Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz, M.; Slabbert, E. The relevance of the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism on selected South African communities. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2016, 14, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; Caballero, R.; González, M.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; Pérez, F. Goal programming synthetic indicators: An application for sustainable tourism in Andalusian coastal counties. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2158–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Maqueo, O.; Martínez, M.L.; Cóscatl Nahuacatl, R. Is the protection of beach and dune vegetation compatible with tourism? Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-L.; Backman, K.F.; Chih Huang, Y. Creative tourism: A preliminary examination of creative tourists’ motivation, experience, perceived value and revisit intention. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 8, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Tepanon, Y.; Uysal, M. Measuring tourist satisfaction by attribute and motivation: The case of a naturebased resort. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molera, L.; Pilar Albaladejo, I. Profiling segments of tourists in rural areas of South-Eastern Spain. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paker, N.; Vural, C.A. Customer segmentation for marinas: Evaluating marinas as destinations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Segarra-Oña, M.; Carrascosa-López, C. Segmentation and motivations in eco-tourism: The case of a coastal national park. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 178, 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C. Marine Tourist Motivations Comparing Push and Pull Factors. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 15, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassean, H.; Gassita, R. Exploring tourists push and pull motivations to visit Mauritius as a tourist destination. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2013, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rid, W.; Ezeuduji, I.O.; Pröbstl-Haider, U. Segmentation by motivation for rural tourism activities in The Gambia. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Motivation and segmentation of the demand for coastal and marine destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, Ö.; Sahin, I.; Ryan, C. Push-motivation-based emotional arousal: A research study in a coastal destination. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.L.; Al-Ansi, A.; Lee, M.J.; Han, H. Impact of health risk perception on avoidance of international travel in the wake of a pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Monitoring the impacts of tourism-based social media, risk perception and fear on tourist’s attitude and revisiting behaviour in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W. Coastal and marine topics and destinations during the COVID-19 pandemic in Twitter’s tourism hashtags. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 1467358421993882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Barbera, P.A.; Mazursky, D. A longitudinal assessment of consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction: The dynamic aspect of the cognitive process. J. Mark. Res. 1983, 20, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turnbull, P.W.; Wilson, D.T. Developing and protecting profitable customer relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1989, 18, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Peppers, D.; Rogers, M. Do You Want to Keep Your Customers Forever? Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/B_Pine_Ii/publication/243782919_Do_You_Want_to_Keep_Your_Customers_Forever_Harvard_Business_Rev/links/56dd9e4408aed4e2a99c53ed/Do-You-Want-to-Keep-Your-Customers-Forever-Harvard-Business-Rev.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Bauer, H.H.; Grether, M.; Leach, M. Building customer relations over the Internet. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2002, 31, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Holland, S.; Han, H.-S. A Structural Model for Examining how Destination Image, Perceived Value, and Service Quality Affect Destination Loyalty: A Case Study of Orlando. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiumsak, T.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Factors influencing international visitors to revisit Bangkok, Thailand. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 4, 220–230. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Athapol_Ruangkanjanases/publication/283179233_Factors_Influencing_International_Visitors_to_Revisit_Bangkok_Thailand/links/5b11857ba6fdcc4611dbbe36/Factors-Influencing-International-Visitors-to-Revisit-Bangkok-Thailand.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; Vinzi, V.E.; O’Connor, P. Examining the effect of novelty seeking, satisfaction, and destination image on tourists’ return pattern: A two factor, non-linear latent growth model. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De San Eugenio, J.; Ginesta, X.; Compte-Pujol, M.; Frigola-Reig, J. Building a place brand on local assets: The case of the Pla De L’estany district and its rebranding. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goffi, G.; Cladera, M.; Pencarelli, T. Does sustainability matter to package tourists? The case of large-scale coastal tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyen, K.N.; Nghi, N.Q. Impacts of the tourists’ motivation to search for novelty to the satisfaction and loyalty to a destination of Kien Giang marine and coastal adventure tourism. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Econ. Res. 2019, 4, 2807–2818. Available online: http://www.ijsser.org/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Sangpikul, A. The effects of travel experience dimensions on tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: The case of an island destination. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 12, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Paradise for who? Segmenting visitors’ satisfaction with cognitive image and predicting behavioural loyalty. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fianto, A.Y.A. Satifaction as intervening for the antecedents of intention to revisit: Marine tourism context in East Java. Relasi J. Ekon. 2020, 16, 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New York Times. 52 Places to Go in 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/travel/places-to-visit.html (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- World Travel Awards. South America’s Leading Business Hotel 2019. Available online: https://www.worldtravelawards.com/award-south-americas-leading-business-hotel-2019 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- United Nations UN COP 20. Available online: https://www.cop20.pe/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- World Travel Awards. South America’s Leading Culinary Destination 2019. Available online: https://www.worldtravelawards.com/award-south-americas-leading-culinary-destination-2019 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- World Travel Awards. South America’s Leading Cultural Destination 2019. Available online: https://www.worldtravelawards.com/award-south-americas-leading-cultural-destination-2019 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H.; Tseng, C.H.; Lin, Y.F. Segmentation by recreation experience in island-based tourism: A case study of Taiwan’s Liuqiu Island. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Park, D.-B. Relationships Among Perceived Value, Satisfaction, and Loyalty: Community-Based Ecotourism in Korea. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Odar, D.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Vara-Horna, A.; Chafloque-Cespedes, R.; Sekar, M.C. Validity and reliability of the questionnaire that evaluates factors associated with perceived environmental behavior and perceived ecological purchasing behavior in Peruvian consumers. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 16, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Factor | Category | N = 381 | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | National | 179 | 47.1 |

| Foreign | 201 | 52.9 | |

| Origin by continent | North America | 20 | 5.3 |

| Europe | 46 | 12.1 | |

| South America | 309 | 81.3 | |

| Rest of the world | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Gender | Male | 216 | 56.8 |

| Female | 164 | 43.2 | |

| Marital status | Single | 239 | 62.9 |

| Married | 115 | 30.3 | |

| Other | 26 | 6.8 | |

| Age | <20 | 18 | 4.7 |

| 21–30 | 129 | 33.9 | |

| 31–40 | 134 | 35.3 | |

| 41–50 | 52 | 13.7 | |

| 51–60 | 31 | 8.2 | |

| >60 | 16 | 4.2 | |

| Level of education | Primary | 1 | 0.3 |

| Secondary | 78 | 20.5 | |

| University | 248 | 65.3 | |

| Postgraduate/Master’s/PhD | 53 | 13.9 | |

| Employment | Student | 44 | 11.6 |

| Researcher/scientist | 16 | 4.2 | |

| Businessman | 76 | 20.0 | |

| Private employee | 156 | 41.1 | |

| Public employee | 40 | 10.5 | |

| Retired | 13 | 3.4 | |

| Unemployed | 18 | 4.7 | |

| Other | 17 | 4.5 | |

| Number of times travelled ever | First time | 119 | 31.3 |

| 2 times | 75 | 19.7 | |

| 3 times | 73 | 19.2 | |

| More than 3 times | 113 | 29.7 | |

| Travel partners | None | 58 | 15.3 |

| Family | 94 | 24.7 | |

| Friends | 140 | 36.8 | |

| A partner | 69 | 18.2 | |

| Other | 19 | 5.0 | |

| Travel duration | 1 day | 32 | 8.4 |

| 2 days–1 night | 78 | 20.5 | |

| 3 days–2 nights | 101 | 26.6 | |

| 4 days–3 nights | 42 | 11.1 | |

| 5 days–4 nights | 47 | 12.4 | |

| More than 5 days | 80 | 21.1 | |

| Average daily total expenditures | Less than USD 50 | 251 | 66.1 |

| USD 50–99 | 88 | 23.2 | |

| USD 100–149 | 31 | 8.2 | |

| USD 150–199 | 9 | 2.4 | |

| USD 200–249 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Variable | Component | Factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Importance of Lima’s history & culture | 0.788 | Culture and nature | |||||

| Importance of coastal and marine tourism | 0.759 | ||||||

| Historical attractions experiences | 0.752 | ||||||

| Experience national parks and marine wildlife sites | 0.699 | ||||||

| Real culture and traditions experiences | 0.696 | ||||||

| Importance of tourism in natural areas | 0.693 | ||||||

| Typical gastronomy of Lima | 0.628 | ||||||

| Stay among the local population | 0.813 | Authentic coastal experience | |||||

| Share interesting experiences with the coastal population | 0.740 | ||||||

| Access to rural farm goods | 0.644 | ||||||

| Strong feelings of experiences lived | 0.632 | ||||||

| Lifestyle of the coastal population of Lima | 0.553 | ||||||

| Experience related to the coastal landscape of Lima | 0.533 | ||||||

| Visit family and friends | 0.704 | Novelty and social interaction | |||||

| For its tourist attractions | 0.638 | ||||||

| To know the flora and fauna | 0.609 | ||||||

| Environmental quality of air, water, and soil | 0.593 | ||||||

| I want to see the things that I normally do not see | 0.582 | ||||||

| Security and protection | 0.568 | ||||||

| Interest in myths and legends | 0.772 | Learning | |||||

| Learn traditional languages of Lima | 0.746 | ||||||

| Interest in coastal handicrafts | 0.690 | ||||||

| Learn traditional dances | 0.648 | ||||||

| Importance of swimming | 0.819 | Sun and beach | |||||

| Importance of water sports | 0.738 | ||||||

| Importance of sun-beach tourism | 0.545 | ||||||

| Nightlife | 0.925 | Nightlife | |||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.71 | - | |

| Eigenvalue | 11.28 | 1.98 | 1.81 | 1.16 | 1.07 | 1.03 | |

| Variance explained (%) | 41.79 | 7.35 | 6.69 | 4.28 | 3.98 | 3.80 | |

| Cumulative variance explained (%) | 41.79 | 49.14 | 55.84 | 60.11 | 64.09 | 67.89 | |

| Variable | Beta | t | Sig. | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novelty and social interaction | 0.305 | 6.392 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Sun–beach | 0.163 | 3.410 | 0.001 | 1.000 |

| Authentic coastal experience | 0.132 | 2.774 | 0.006 | 1.000 |

| Learning | 0.105 | 2.201 | 0.028 | 1.000 |

| (Constante) | 103.985 | 0.000 | ||

| Adj. R2 | 0.139 | |||

| F statistic | 16.258 | |||

| Sig. | 0.000 | |||

| Durbin–Watson | 2.001 |

| Variable | Beta | t | Sig. | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic coastal experience | 0.182 | 3.724 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Learning | 0.176 | 3.589 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Novelty–social interaction | 0.145 | 2.962 | 0.003 | 1.000 |

| Culture–nature | 0.120 | 2.453 | 0.015 | 1.000 |

| (Constante) | 127.482 | 0.000 | ||

| Adj. R2 | 0.090 | |||

| F statistic | 10.386 | |||

| Sig. | 0.000 | |||

| Durbin-Watson | 1.682 |

| Variable | Beta | t | Sig. | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic coastal experience | 0.249 | 5.239 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Culture and nature | 0.223 | 4.690 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Sun and beach | 0.166 | 3.499 | 0.001 | 1.000 |

| Novelty and social interaction | 0.111 | 2.338 | 0.020 | 1.000 |

| (Constante) | 140.768 | 0.000 | ||

| Adj. R2 | 0.143 | |||

| F statistic | 16.786 | |||

| Sig. | 0.000 | |||

| Durbin–Watson | 1.827 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carvache-Franco, M.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Estrada-Merino, A.; Rosen, M.A. Coastal Cities Seen from Loyalty and Their Tourist Motivations: A Study in Lima, Peru. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11575. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111575

Carvache-Franco M, Alvarez-Risco A, Carvache-Franco W, Carvache-Franco O, Estrada-Merino A, Rosen MA. Coastal Cities Seen from Loyalty and Their Tourist Motivations: A Study in Lima, Peru. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):11575. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111575

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarvache-Franco, Mauricio, Aldo Alvarez-Risco, Wilmer Carvache-Franco, Orly Carvache-Franco, Alfredo Estrada-Merino, and Marc A. Rosen. 2021. "Coastal Cities Seen from Loyalty and Their Tourist Motivations: A Study in Lima, Peru" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 11575. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111575

APA StyleCarvache-Franco, M., Alvarez-Risco, A., Carvache-Franco, W., Carvache-Franco, O., Estrada-Merino, A., & Rosen, M. A. (2021). Coastal Cities Seen from Loyalty and Their Tourist Motivations: A Study in Lima, Peru. Sustainability, 13(21), 11575. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111575