Spatio-Temporal Clustering of Sarawak Malaysia Total Protected Area Visitors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Description

3.2. Spatial and Temporal Analysis

3.3. Euclidean Distance

3.4. Ward Hierarchical Linkage Clustering

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

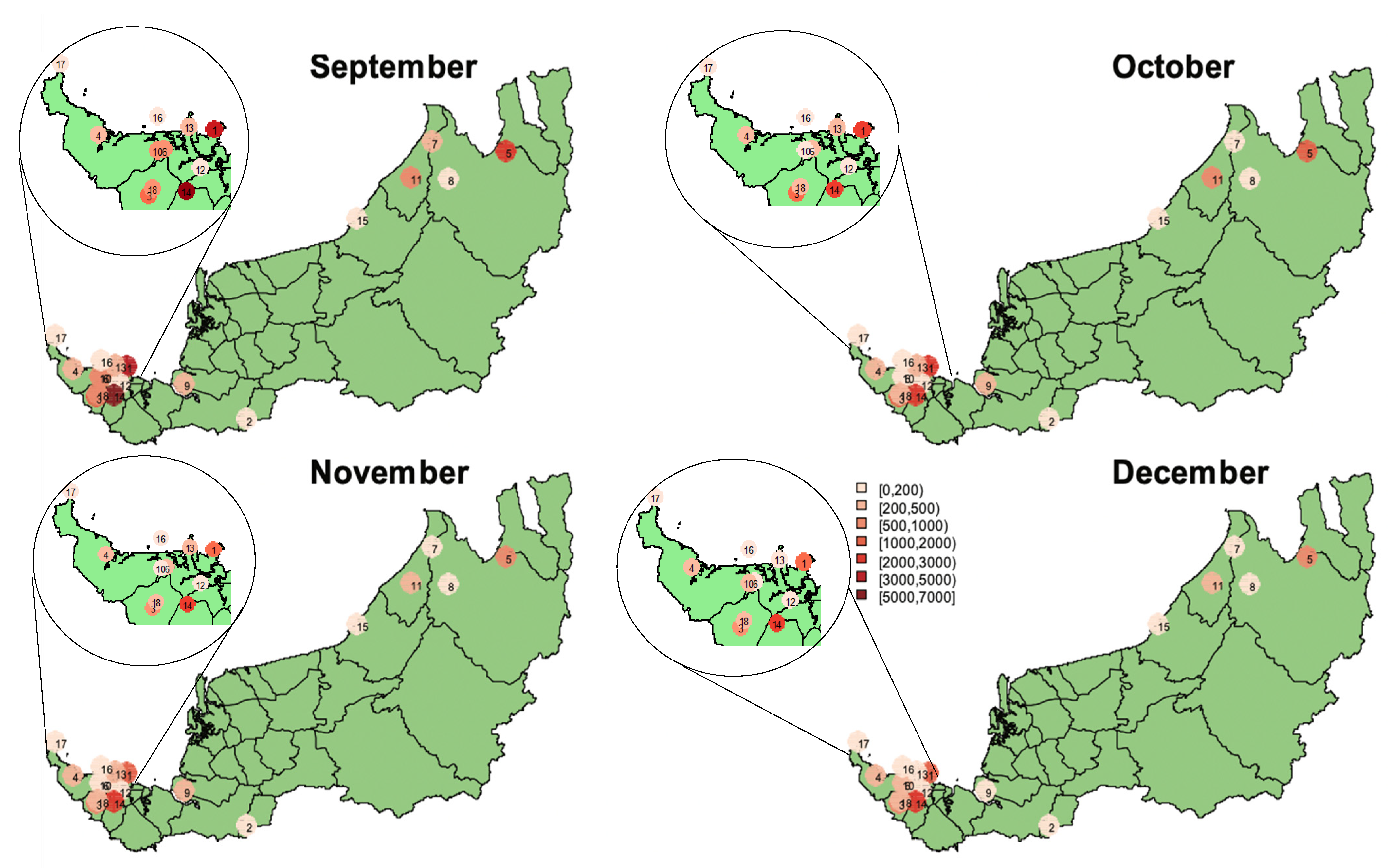

4.2. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of Local and Foreign Visitors by Park in Sarawak

4.3. Clustering Analysis of Local and Foreign Visitors of TPAS in Sarawak

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Urioste-Stone, S.M.; Scaccia, M.D.; Howe-Poteet, D. Exploring visitor perceptions of the influence of climate change on tourism at Acadia National Park, Maine. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015, 11, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Piñeros, S.; Mayett-Moreno, Y. Forest owners’ perceptions of ecotourism: Integrating community values and forest conservation. Ambio 2015, 44, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jaafar, M.; Kayat, K.; Tangit, T.M.; Yacob, M.F. Nature-based rural tourism and its economic benefits: A case study of Kinabalu National Park. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2013, 5, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, E.V.; Souza, T.B.; Thapa, B. Determinants of tourism attractiveness in the national parks of Brazil. Parks 2015, 21, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Stemberk, J. Factors Affecting the Number of Visitors in National Parks in the Czech Republic, Germany and Austria. Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forest Department Sarawak. Totally Protected Area (TPAS). Available online: https://forestry.sarawak.gov.my/modules/web/pages.php?mod=webpage&sub=page&id=661# (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Department of Statistic Malaysia. Regional Tourism Satellite Account Sarawak. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/pdfPrev&id=Qlc3cW5WRkE5cEtKYStkaUs1UzNJdz09 (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Dzhandzhugazova, E.A. New forms and possibilities for promotion of Russian national parks in the internet environment. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 16, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duzgunes, E.; Demirel, O. Importance of Visitor Management in National Park Planning. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2016, 17, 675–680. [Google Scholar]

- Lacher, R.G.; Brownlee, M.T. Determinates of clustering across America’s national parks: An application of the Gini coefficients. In Fisher, Cherie LeBlanc; Watts, C.E., Jr., Ed.; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli, R.M.; Romagnoli, L. Customer satisfaction with farmhouse facilities and its implications for the promotion of agritourism resources in Italian municipalities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Botha, E.; Saayman, M.; Kruger, M. Clustering Kruger National Park visitors based on interpretation. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 47, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P.; De Giovanni, L.; Disegna, M.; Massari, R.; Vitale, V. A Tourist Segmentation Based on Motivation, Satisfaction and Prior Knowledge with a Socio-Economic Profiling: A Clustering Approach with Mixed Information. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 154, 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. A review of data-driven market segmentation in tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Disegna, M.; Cohen, S.A.; Yan, H. Segmenting markets by bagged clustering: Young Chinese travelers to Western Europe. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ernst, D.; Dolnicar, S. How to avoid random market segmentation solutions. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barić, D.; Anić, P.; Bedoya, A. Segmenting protected area visitors by activities: A case study in Paklenica National Park, Croatia. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 13, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D. Residents’ place image: A cluster analysis and its links to place attachment and support for tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veisten, K.; Grue, B.; Haukeland, J.V.; Degnes-Ødemark, H.; Baardsen, S. Tourist segments for new facilities in an alpine national park area: Profiling tourists in Norway based on psychographics and demographics. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium for Research in Protected Areas, Osttirol, Austria, 10–12 June 2013; pp. 773–782. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, M.; Roman, M.; Prus, P.; Szczepanek, M. Tourism Competitiveness of Rural Areas: Evidence from a Region in Poland. Agriculture 2020, 10, 569. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, M.; Roman, M.; Niedziółka, A. Spatial Diversity of Tourism in the Countries of the European Union. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2713. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.A.; Wichern, D.W. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson New International Edition: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, F.; Legendre, P. Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: Which algorithms implement Ward’s criterion? J. Classif. 2014, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lattin, J.; Carroll, J.D.; Green, P.E. Analyzing Multivariate Data; Thomson Learning. Inc.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, T.; von Maltitz, M.J. Generalising Ward’s method for use with Manhattan distances. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| No | Totally Protected Area (TPAS) | Size (km2) | Distance (km) to Nearest City | Year of Gazetted | Local Visitors 2019 | Local Visitors/km2 | Foreign Visitors 2019 | Foreign Visitors/km2 | Latitude ‘N | Longitude ‘E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bako National Park | 27.27 | 23.2 | 1957 | 19,941 | 731.24 | 40,406 | 1481.70 | 1.7167 | 110.4667 |

| 2. | Batang Ai National Park | 240.40 | 54.0 | 1991 | 31 | 0.13 | 50 | 0.21 | 1.1472 | 111.8743 |

| 3. | Fairy Cave Nature Reserve | 0.56 | 42.3 | 2013 | - | - | - | - | 1.3818 | 110.1172 |

| 4. | Gunung Gading National Park | 54.30 | 85.2 | 1983 | 9755 | 179.65 | 4164 | 76.69 | 1.6906 | 109.8458 |

| 5. | Gunung Mulu National Park | 857.71 | 106.0 | 1974 | 5976 | 6.97 | 15,046 | 17.54 | 4.0921 | 114.8958 |

| 6.. | Kubah National Park | 22.30 | 23.3 | 1989 | 10,833 | 485.78 | 5143 | 230.63 | 1.6128 | 110.1969 |

| 7. | Lambir Hills National Park | 69.49 | 32.3 | 1975 | 10,479 | 150.80 | 2679 | 38.55 | 4.1984 | 114.0429 |

| 8. | Loagan Bunut National Park | 107.36 | 117.0 | 1991 | 462 | 4.30 | 47 | 0.44 | 3.7775 | 114.2272 |

| 9. | Maludam National Park | 535.68 | 48.00 | 2000 | 20 | 0.04 | 8 | 0.01 | 1.5271 | 111.1414 |

| 10. | Matang Wildlife Centre | 1.80 | 33.2 | 1997 | 25,463 | 14,146.11 | 4909 | 2727.22 | 1.6094 | 110.1602 |

| 11. | Niah National Park | 31.38 | 90.0 | 1975 | 19,319 | 615.65 | 5188 | 165.33 | 3.8014 | 113.7841 |

| 12. | Sama Jaya Nature Reserve | 0.379 | 8.4 | 2000 | 118,434 | 312,490.77 | 2176 | 5741.42 | 1.5197 | 110.3890 |

| 13. | Santubong National Park | 16.41 | 35.3 | 2007 | 15,508 | 945.03 | 3789 | 230.90 | 1.7333 | 110.3333 |

| 14. | Semenggoh Nature Reserve | 6.53 | 22.0 | 2000 | 46,305 | 7091.12 | 49,691 | 7609.65 | 1.4017 | 110.3145 |

| 15. | Similajau National Park | 89.96 | 28.8 | 1978 | 12,376 | 137.57 | 1141 | 12.68 | 3.3483 | 113.1564 |

| 16. | Talang Satang National Park | 194.14 | 33.6 | 1999 | 87 | 0.45 | 669 | 3.45 | 1.7843 | 110.1643 |

| 17. | Tanjung Datu National Park | 13.79 | 140.0 | 1994 | 922 | 66.86 | 795 | 57.65 | 2.0554 | 109.6422 |

| 18. | Wind Cave Nature Reserve | 0.0616 | 37.6 | 1999 | 11,690 | 189,772.73 | 4152 | 67,402.60 | 43.6046 | 103.4213 |

| Variables | Measurement Unit | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Name of the Park | Name | Name of the Park |

| Number of visitors | Count | Number of visitors |

| Latitude | °N | Latitude |

| Longitude | °E | Longitude |

| No | National Park 1 | 2015 1 | 2018 1 | 2019 1 | 1 Year Growth (%) (2018–2019) | 5 Years Growth (%) (2015–2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bako National Park | 28,211 | 40,382 | 40,406 | 0.06 | 43.23 |

| 2. | Batang Ai National Park | 24 | 33 | 50 | 51.52 | 108.33 |

| 3. | Fairy Cave Nature Reserves | 5081 | 7118 | Under renovation | - | - |

| 4. | Gunung Gading National Park | 2082 | 3491 | 3164 | −9.37 | 51.97 |

| 5. | Gunung Mulu National Park | 12,843 | 15,850 | 15,046 | −5.07 | 17.15 |

| 6. | Kubah National Park | 3163 | 4873 | 5143 | 5.54 | 62.60 |

| 7. | Lambir Hills National Park | 3401 | 2450 | 2679 | 9.35 | −21.23 |

| 8. | Loagan Bunut National Park | 51 | 42 | 47 | 11.90 | −7.84 |

| 9. | Maludam National Park | 6 | 2 | 8 | 300 | 33.33 |

| 10. | Matang Wildlife Centre | 3690 | 4434 | 4909 | 10.71 | 33.04 |

| 11. | Niah National Park | 5189 | 6210 | 5188 | −16.46 | −0.02 |

| 12. | Sama Jaya Nature Reserves | 3941 | 2492 | 2176 | −12.68 | −44.79 |

| 13. | Santubong National Park | 2017 | 3828 | 3789 | −1.02 | 87.85 |

| 14. | Semenggoh Nature Reserve | 30,335 | 43,255 | 49,691 | 14.88 | 63.81 |

| 15. | Similajau National Park | 2676 | 1823 | 1141 | −37.41 | −57.36 |

| 16. | Talang Satang National Park | 963 | 514 | 669 | 30.16 | −30.53 |

| 17. | Tanjung Datu National Park | 477 | 599 | 795 | 32.72 | 66.67 |

| 18. | Wind Cave Nature Reserves | 3761 | 5150 | 4152 | −19.38 | 10.40 |

| Total | 107,911 | 142,996 | 139,053 |

| No | National Park 1 | 2015 1 | 2018 1 | 2019 1 | 1 Year Growth (%) (2018–2019) | 5 Years Growth (%) (2015–2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bako National Park | 17,896 | 22,964 | 19,941 | −13.16 | 11.43 |

| 2. | Batang Ai National Park | 50 | 10 | 31 | 67.74 | −38.00 |

| 3. | Fairy Cave Nature Reserves | 20,146 | 17,729 | - | - | - |

| 4. | Gunung Gading National Park | 16,185 | 15,707 | 9755 | −37.89 | −39.73 |

| 5. | Gunung Mulu National Park | 5780 | 5815 | 5976 | 2.77 | 3.39 |

| 6.. | Kubah National Park | 11,727 | 14,011 | 10,833 | −22.68 | −7.62 |

| 7. | Lambir Hills National Park | 12,902 | 9360 | 10,479 | 11.96 | −18.78 |

| 8. | Loagan Bunut National Park | 1048 | 382 | 462 | 20.94 | −55.92 |

| 9. | Maludam National Park | - | 50 | 20 | −60.00 | - |

| 10. | Matang Wildlife Centre | 33,162 | 32,438 | 25,463 | −21.50 | −23.22 |

| 11. | Niah National Park | 21,866 | 20,226 | 19,319 | −4.48 | −11.65 |

| 12. | Sama Jaya Nature Reserves | 169,756 | 162,747 | 118,434 | −27.23 | −30.23 |

| 13. | Santubong National Park | 8074 | 22,216 | 15,508 | −30.19 | 92.07 |

| 14. | Semenggoh Nature Reserve | 46,304 | 45,983 | 46,305 | 0.70 | 0.00 |

| 15. | Similajau National Park | 23,509 | 9652 | 12,736 | 31.95 | −45.83 |

| 16. | Talang Satang National Park | 266 | 189 | 87 | −53.97 | −67.29 |

| 17. | Tanjung Datu National Park | 536 | 963 | 922 | −4.26 | 72.01 |

| 18. | Wind Cave Nature Reserves | 23,911 | 18,193 | 11,690 | −35.74 | −51.11 |

| Total | 413,118 | 398,635 | 307,961 |

| Very High Visitors | High Visitors | Medium Visitors | Low Visitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sama Jaya | Semenggoh | Matang Bako Niah Similajau Fairy Cave Santubong Wind Cave Kubah Gunung Gading Lambir Hills | Gunung Mulu Talang Satang Batang Ai Maludam Loagan Bunut Tanjung Datu |

| Very High Visitors | High Visitors | Medium Visitors | Least Visitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bako Semenggoh | Gunung Mulu | Similajau Lambir Hills Sama Jaya Gunung Gading Kubah Santubong Fairy Cave Niah Matang Wind Cave | Loagan Bunut Batang Ai Maludam Talang Satang Tanjung Datu |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abang Abdurahman, A.Z.; Md Nasir, S.A.; Wan Yaacob, W.F.; Jaya, S.; Mokhtar, S. Spatio-Temporal Clustering of Sarawak Malaysia Total Protected Area Visitors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111618

Abang Abdurahman AZ, Md Nasir SA, Wan Yaacob WF, Jaya S, Mokhtar S. Spatio-Temporal Clustering of Sarawak Malaysia Total Protected Area Visitors. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):11618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111618

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbang Abdurahman, Abang Zainoren, Syerina Azlin Md Nasir, Wan Fairos Wan Yaacob, Serah Jaya, and Suhaili Mokhtar. 2021. "Spatio-Temporal Clustering of Sarawak Malaysia Total Protected Area Visitors" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 11618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111618

APA StyleAbang Abdurahman, A. Z., Md Nasir, S. A., Wan Yaacob, W. F., Jaya, S., & Mokhtar, S. (2021). Spatio-Temporal Clustering of Sarawak Malaysia Total Protected Area Visitors. Sustainability, 13(21), 11618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111618